By Eric Niderost

In the fall of 1447, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, was not a happy man. He was lieutenant general of France and Guyenne, a kind of viceroy who oversaw English possessions in France, and he was also a powerful and rapacious feudal magnate in his own right. King Henry VI had recently written him, ordering the duke to abide by the terms of an Anglo-French truce and give up the province of Maine, including particularly the key city of Le Mans. Somerset was reluctant to give the French such an important prize—and such an important source of revenue. He had been promised Maine in the past, and he wasn’t about to surrender it to an upstart French king. Somerset dragged his feet, stalling for time by requesting a conference to settle the matter.

The French were rapidly losing patience, and in March 1448 a large army under John, Count of Dunois, appeared before the gates of Le Mans. Nicknamed the “Bastard of Orleans” because of his illegitimate birth, Dunois had won his spurs under the legendary Joan of Arc. Now he was one of France’s most formidable commanders, and he had a large siege train equipped with the latest in artillery. Faced with a choice between surrender or siege, the English chose the former. The garrison marched out—only to find that no one would take them in. Most of the major towns in English-occupied France had large contingents of men-at-arms to enforce their rule, but each garrison greedily guarded its prerogatives. Local French townsmen were supposed to feed each garrison, and if the Le Mans garrison was added to the rolls, there might be shortages. The now-homeless English were left to their own devices.

Somerset’s preoccupation with feudal acquisitions and his own basic incompetence proved to be his undoing. His capital was at Rouen, in Normandy, the very heart of English-occupied France. The English presence in the conquered territories was shrinking, and every man was needed if France was to be held. The Le Mans garrison could have bolstered Rouen’s defenses. Instead, Somerset abandoned Le Mans, leaving the soldiers to their own devices. To survive, they established themselves at Saint-James-de-Beuvron and Mortain, two dismantled fortresses on the border of Brittany. The English soldiers repaired the battlements and used the towns as bases to plunder the countryside.

Francis, Duke of Brittany, protested. Although very much under English dominance, he was nominally independent and was forging ties with the French king, Charles VII. The homeless English soldiers, who had become little better than brigands, attacked and sacked the Breton town of Fougeres, an important center of the province. Somerset disclaimed all responsibility, but there was a good chance that he had some connection in the affair—perhaps even shared in the spoils. It was hard for Charles VII to believe that the leader of the sack, Francois de Suriennes, did not have at least Somerset’s tacit permission. After all, Suriennes was one of the duke’s senior commanders.

French grievances began to mount, and Charles VII grew tired of Somerset’s delays and prevarications. Perhaps there was some method to Somerset’s incompetence and lack of control over subordinates, the French monarch wondered. Perhaps those English soldiers had been purposely refused a home so that they would ultimately sack Fougeres and scare the Duke of Brittany into renewed loyalty to England. In any case, enough was enough. Charles decided to end English duplicity with an invasion of Normandy. The invasion, begun in July 1449, started the last phase of the Hundred Years’ War.

The concluding chapter of the off-and-on war traced its roots to the ambitions of another English king, Henry V, 35 years earlier. Young, bellicose, relentless, and rapacious, Henry wished to renew England’s dormant claims to the throne of France. The time seemed right, because the current French monarch, King Charles VI, was prone to intermittent fits of madness. Charles lived in a twilight world of mental illness, at one point refusing to bathe, shave, or change clothes for months on end; another time he believed that he was made entirely of glass. In the absence of a strong ruler, feudal magnates vied for power and France descended into political chaos.

The Empire of Henry V

In 1415, Henry V invaded France and took Harfleur after a brief siege. He then decided that the English Army would go on a chevaunchee, or extended raid, across northern France. But autumn rains drenched the invaders and rations grew short as they marched toward Calais. Sickness spread through the ranks, and dysentery laid many low. The French Army caught up with the English near the village of Agincourt. The English flanks were protected on each side by woods, but the French were confident of victory. They had around 30,000 men, while the English had around 6,000 diseased-wracked longbowmen and men-at-arms. Recklessly charging the English ranks, the heavily armored French nobles were decimated by showers of arrows launched by skilled longbowmen. Mired in the mud and pelted by hundreds of lethal shafts, the bunched-up French knights and men-at-arms died by the thousands.

Agincourt became more than just a victory against great odds—it became an English national epic, commemorated by story and song throughout the ages. The longbowmen, in particular, came to be celebrated for their steely performance at Agincourt. And indeed, the idea of a common archer bringing down the flower of French chivalry was something unique in medieval history.

In the years following Agincourt, Henry went from triumph to triumph. He signed an important alliance with Philip the Good, the ruler of Burgundy, a powerful state on the eastern flanks of France. By 1420, much of northern France was under English rule. Henry capped his battlefield successes with victory on the diplomatic front. The Treaty of Troyes made the English king the heir to the French throne after Charles VI’s passing. Sad, demented Charles hardly knew where he was, much less the details of the treaty that disinherited his son, the Dauphin, in favor of Henry V. The pact was negotiated by Charles’s queen, Isabeau of Bavaria, who also granted Henry the hand of their daughter, Catherine of Valois.

Henry’s actions were those of a feudal lord seeking to gain more lands and revenues. There was no thought as to the culture, language, and traditions of the subject peoples. Peasant serfs were mere pawns in the larger game of dynastic chess. Henry meant to make his conquest of France permanent. If he succeeded, he would equal if not surpass the old empire of Henry II and Richard the Lionheart. But the king’s calculations did not take into account the unsanitary conditions of the 15th century. In 1422, Henry contracted dysentery at the height of his power. Dehydration and death soon followed. Ironically, mad King Charles died a couple of months later, creating a dual monarchy under Henry’s nine-month-old son, Henry VI.

Joan of Arc: Awakening the Spirit of French Nationalism

For the next few years, it seemed as though the late king’s dynastic dreams would continue without him. John, Duke of Bedford, became primary regent for his royal nephew. Bedford was a good soldier, and English fortunes in France flourished. By 1429, virtually all of northern France was under English or Burgundian rule. Regions south of the Loire River, however, were still loyal to the Dauphin, who considered himself Charles VII.

The strategic city of Orleans was the dam that blocked English progress in the south. Once Orleans fell, English and Burgundian armies could flood into the region, taking control of all of France. Orleans was put under siege, and the fate of France hung in the balance. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Joan of Arc appeared on the scene. A 17-year-old peasant girl, Joan claimed that she was an instrument of God, sent to deliver France from the English and to see the Dauphin crowned king. Under her divine inspiration, the French miraculously lifted the siege of Orleans, and Joan did indeed see Charles VII crowned king at Reims before she was captured and eventually burned at the stake as a heretic and witch by her English and Burgundian enemies in 1431.

Joan had good strategic sense for a medieval saint. She recognized that the English had to be expelled from all of France. The Maid would accept no compromise. The “goddams”—a popular common term for the English, due to their habitual use of profanity—must go back to their island home. Prolonged truces that allowed them to control large territories inside France only prolonged the agony.

Joan also awakened something that was rare in the 15th century: a spirit of nationalism. France was a patchwork of feudal holdings, and most of its people were illiterate peasants. But there was also a growing sense of a French national identity, a feeling that the English were foreign invaders who were exploiting someone else’s homeland. Henry V’s dream of a great empire in which France would be incorporated into England died with the English defeat at Orleans. Yet the dream died hard, and the English were not going to leave without a protracted struggle. Normandy had been English until 1204, when it had been lost. Its possession seemed a coming home, not a conquest, to most Englishmen. England had its own national spirit, and English honor and prestige were at stake.

Improving Royal Finances

It all depended on King Charles VII, and he rose to the challenge. In his early youth he was considered a cipher, a nonentity, and there were rumors that he might have been illegitimate, a by-product of Charles VI’s unfaithful and promiscuous queen. He had done nothing to save Joan of Arc, which had also sullied his reputation. Yet Joan’s inspiration, and his own slowly developing maturity, had transformed the former figurehead into a monarch of real substance. He was cunning and unscrupulous, and he had the invaluable ability to pick the right people for the right job. He realized that France’s economy and military had to be reformed if the country was to have any hope of success against the English.

First, Charles scored a major coup on the diplomatic front. In 1435, Philip the Good abandoned the English alliance and came over to the French. This was a serious blow to the English cause. At the same time, King Henry VI came of age, but at 16 he was still too weak, tenderhearted, and overtly religious to rule effectively. Counselors such as Cardinal Henry Beaufort saw the handwriting on the wall, but English prestige would not permit a withdrawal from France.

Jacques Coeur, a merchant prince who was one of the richest men in Europe, was selected to oversee French royal finances. Coeur established a gold standard, stabilized the currency, and rid the country of the debased coinage that had been circulating for decades. This was a good start, but more was needed. Charles summoned an Estates-General in 1439, which gladly rubber-stamped a series of laws (ordonnances) that overhauled the tax system of the country. Taxes that once went into feudal lords’ coffers now went directly to the king. Government revenue was boosted by 1.8 million crowns, and the power of the feudal nobility concomitantly diminished.

Reorganizing the Army

Now that there was money to pay for a permanent force, the Army could be reformed. Before the 1440s, the bulk of the French Army consisted of feudal levies, peasants who were called up for service in time of war. Untrained, literally fresh off the farm, they gave the Army bulk but not substance. Poorly armed, they might take to their heels at any time. The lesser knights and men-at-arms were better soldiers, but the French Army typically disbanded after a war, giving the professionals nothing to do. Unemployed and virtual outcasts, many turned to robbery to survive. Roving bands of soldiers-turned-brigands were as much a threat to the common people as the English invaders.

Charles was determined to change all that. In 1444, after the latest truce with the English, the king did not disband the Royal Army. Instead, Arthur de Richemont, the Constable of France, was directed to reform the army into a more permanent and effective fighting force. Undisciplined soldiers, or those known to lapse into brigandage, were dismissed from the king’s service. In November 1439, Charles declared that military recruiting was a royal privilege. No longer would nobles of dubious motives and questionable loyalty be permitted to raise men from their own lands. Men-at-arms would be trained troops, not peasant rabble, and permanent royal garrisons would be established throughout the country.

Taxes paid by local townsmen and landowners would support the maintenance of these garrisons. Most people gladly accepted the new rules, feeling that it was better to pay a tax than to be beaten and robbed by rampaging soldiers. For the first time, France had a permanent standing army. Charles felt that quality was better than mere quantity. The king’s newly streamlined cavalry force was dubbed companies of the king’s ordinance or compagnies d’ordonnance. They were organized into smaller groups, called lances. Each lance consisted of a man-at-arms, his servant or page, and three to five lightly armed attendants. In all, Charles counted 15,000 lances among his troops.

For infantry, Charles could rely on trained men-at-arms in the various garrison towns. At the same time, he issued an order that each parish in France pay for the maintenance of an archer. To entice bowmen to join up, Charles decreed that anyone who entered the king’s service would be granted an exemption on all taxes. This gave rise to the name franc-archers or free archers for the men. The free archers were paid nine livres a year and up to four livres a month while on active duty. They were required to train once a week and had to be ready to assemble into their companies at a moment’s notice. On paper, at least, the king could raise some 16,000 infantry when needed.

The Bureau Brothers’ Cannons

The king was fortunate to have the services of Jean Bureau and his brother, Gaspard. Jean had been serving as Charles’s master gunner since 1439, making sure that France had the finest and most up-to-date artillery in Europe. In the 1440s, artillery was still primitive but was light-years ahead of what it had been before. Powder was improving, and after much trial and error the correct proportions of saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal were more or less worked out. Corned powder was also a staple. It was discovered that when dampened, gunpowder formed into cakes. Someone hit upon the idea of grinding up the caked powder to see what would happen. Because the resulting mixture formed lumps with the consistency of grain, it was called “corned.” The corned powder allowed more free oxygen to be present, thus enhancing the burning and explosive properties.

The Bureau brothers’ artillery advances proved their worth in a series of sieges that battered down the walls of English garrison towns. Their bombards, or siege guns, were longer and more efficient, thanks to such innovations as hooped staves that strengthened the guns’ barrels. There was less progress in field artillery, chiefly because of the difficulty of transporting some of the large iron monsters to the battlefield.

The Fall of Rouen

By 1449, Charles was ready to expel the English once and for all. The sack of Fougeres provided the French king with the pretext he needed to renew hostilities. The Normandy campaign opened with a three-pronged attack, with French forces coming in from the north, south, and east. Overall command was entrusted to John Dunois, the famed “Bastard of Orleans.” The count was supported by John, Duke of Alençon, another of Joan of Arc’s veterans, and together they made good progress. Before long, the city of Verneuil fell, along with most of central Normandy. At the same time, the counts of Eu and Saint-Pol recaptured much of eastern Normandy. The third wing was commanded by Arthur de Richemont, Constable of France, who was accompanied by his nephew, Duke Francis of Brittany. They took most of western Normandy, including Fougeres, which fell on November 5.

The French advance met little resistance. The English were demoralized, and many Norman towns simply opened the gates and joyfully admitted their French brothers. Once again, nascent nationalism trumped the feudal dream of foreign empire. The biggest prize was Rouen, capital of English Normandy and the place where Joan of Arc had been burned at the stake 18 years earlier.

The Duke of Somerset remained at Rouen, inert and seemingly powerless to stop the French advance. On October 9, a large French army commanded by King Charles himself hove into view. The Bastard was the real commander, but Charles knew how to play his royal part. The king would show up in armor, on horseback, encourage the troops, and not get in the way. Dunois tried to rush the walls, but the French were beaten back. Old habits die hard, and it was natural for the Bastard to favor old-style offensives. The people of Rouen took matters into their own hands and rioted against their English overlords. They were not about to suffer siege and death in behalf of the hated “goddams.”

The English garrison, faced with enemies from without and within, retreated to the town’s citadel. The people of Rouen opened the gates to Charles, and the French invested the citadel. Somerset had only 1,200 men and very little food. The English nobleman took fright when he saw the Bureau brothers’ guns being brought forward. Stalling for time, Somerset called a truce, meeting King Charles while wearing a long robe of blue velvet trimmed with sable and accompanied by a retinue of 40 knights. Charles was unimpressed. No amount of display would deter him from demanding complete surrender.

After a lengthy negotiation, Somerset capitulated. The terms of the surrender were harsh by medieval standards. The duke was permitted to withdraw to Caen, but he had to promise to pay a huge indemnity of 50,000 gold pieces. To make sure that Somerset did not break his word, the renowned English commander John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, was to remain behind as a hostage. King Charles formally entered Rouen in triumph on November 10. Other English-held towns were taken in turn, some battered into submission by French artillery. By the end of the year, the English retained little but the Cherbourg peninsula.

Sir Thomas Kyriel’s Longbowmen

When news of the staggering setbacks reached England, there was a predictable uproar. Sir Thomas Kyriel began to gather an army at Portsmouth to reinforce what was left of English-held Normandy. Kyriel soon realized that he had a huge problem on his hands. The years of war had made many English soldiers coarse and brutal, a murderous rabble even given the low standards of the 15th century. Kyriel’s troops went wild, drinking and robbing in the English countryside. When he tried to control them, they mutinied. Bad weather completed Kyriel’s litany of woes.

Eventually, Kyriel restored order and landed at Cherbourg on March 15, 1450. He had only about 2,500 men with him. This was a minuscule force, even by medieval standards, and it was ludicrous to think that he could reverse English fortunes with such a small force. England simply did not have the old enthusiasm for war with France. No Englishman wanted to give up Normandy, but the will to fight—a will that a leader such as Henry V might have inspired—was sorely lacking.

Kyriel asked Somerset for more troops, and the duke did the best he could with his own meager resources. By April 1450, Kyriel’s army had increased to around 4,000—800 men-at-arms and the rest longbowmen. Kyriel was originally supposed to march toward Bayeux, but he paused to besiege Valognes and take it from its Breton garrison.

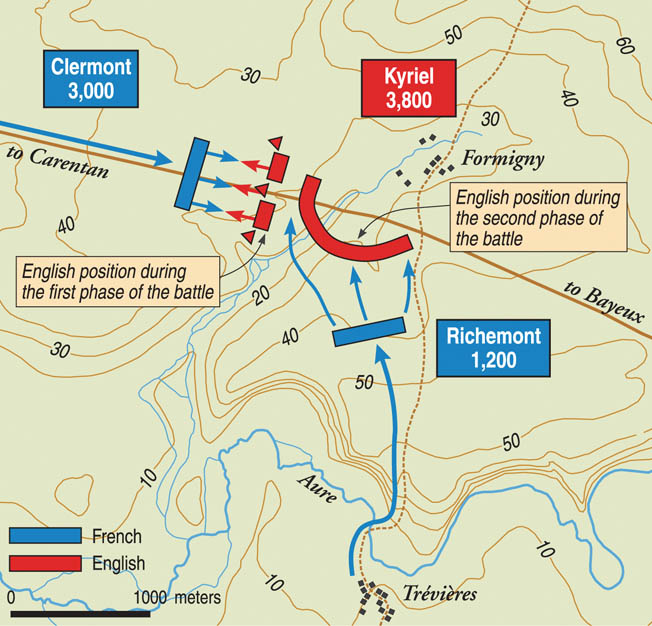

On April 12, Kyriel began his march toward Bayeux. After crossing the estuary of the Vire River, the English camped near the village of Formigny, 10 miles from Bayeux. The morning of April 15 found the English still in camp. Meanwhile, the French had two small armies in the area. The Count of Clermont and 3,000 men were at Carentan, 15 miles away. A second force of 2,000 was led by Arthur of Brittany, Constable de Richemont, who intended to block Kyriel if he could. The constable and his troops were about 19 miles southwest of Formigny.

An Agincourt-Style Position

Clermont, a son of the Duke of Bourbon, marched east with the intention of engaging Kyriel. Before setting out, he took the precaution of sending a message to Richemont, explaining the situation and requesting that they link up. Kyriel’s outposts gave him advance warning of Clermont’s approach, but for some reason he decided to make a stand. He could have found refuge in Bayeux, only a half-day march away. But the English still had confidence that their longbowmen could defeat any French attack. There was ample time for preparations, and the men worked with a will. Trees were cut down and sharpened into defensive stakes, and holes or trenches were dug with daggers and knives in front of the English position. It was hoped these hastily dug moats and cut battlements would stop the enemy in his tracks. They had served the purpose well at Agincourt.

Kyriel arranged his men in classic Agincourt formation—men-at-arms interspersed with wedges of archers. The English position was poor, with the men placed at the bottom of a small valley with no woods to protect their flanks. A small brook meandered immediately behind them, a small finger of water that was spanned by a single stone bridge in the rear of the English center.

Bureau’s Guns at Formingny

The French appeared about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Clermont dismounted his men and attempted a frontal assault. For a moment it seemed that history would repeat itself. Each English archer drew his bow, muscles rippling as the bowstrings stretched to their full 80- to 120-pound draw weight. When the arrow reached to the back of his ear, each archer released the shaft, and thousands of arrows rained down unmercifully on the attacking French. Some of the French reached the English lines, but men-at-arms carrying bills and other pole arms made short work of the attackers. The battered French fell back to their original position. Clermont now tried a mounted assault on both flanks, but that too was beaten back.

The old tactics had failed to work, but the French had one more card to play—the Bureau brothers’ improved artillery. They had two culverins, each mounted on a two-wheel carriage. The French set their guns just out of maximum bow range, about 300 yards. The culverins began to fire, and soon the English longbowmen got a taste of their own long-range medicine. Cannonballs smashed into human flesh, killing and maiming with disconcerting ease. More bowmen fell dead and wounded each passing minute.

After a lengthy pounding, the archers could stand no more. They rushed forward to capture the guns. The French, surprised that usually defensive bowmen were taking the offensive, were easy prey. The guns were captured, but the English did not have long to savor their small victory. French men-at arms counterattacked the English bowmen in flank, recapturing the guns and sending their opponents reeling back to their own lines.

Slaughtered to a Man

In spite of their successes, the French themselves were just about spent. They had been decimated by English arrows, and although the culverins had hurt the enemy, their artillery had not entirely turned the tide. The French were on the verge of retiring when Richemont appeared in the proverbial nick of time with 1,200 additional mounted men.

Seeing the danger, Kyriel was forced to adopt a semicircular half-moon formation to ward off attacks from the west and south. Clermont and his men renewed their attack, heartened by Richemont’s sudden arrival, and the constable’s men joined the fray. The English were stretched thin, and their accustomed rain of arrows became a mere sprinkle. The English line buckled, then broke, after the defenders were hit on two sides by a French enemy that sensed a historic victory. The English made their last stand in some small gardens that lay on the banks of the stream.

French observers admitted that the English “held themselves grandly,” refusing to surrender until all were cut down. It was a moot point because the French hated the English archers, and in most cases only knights or people of quality were spared for ransom. A small knot of survivors under Kyriel’s second in command, Sir Matthew Gough, managed to cut its way out and escaped to Bayeux. Kyriel himself was captured, but the rest of his army was slaughtered almost to a man. English casualties included 3,774 dead. The French lost only around 200.

The Death of the Long Bow, the Rise of the Cannon

Formigny, the greatest English defeat since Bannockburn in 1314, was the penultimate act in the ongoing drama of Charles VII’s reconquest of France. Artillery played an important role in the battle, but it was the timely appearance of Richemont, not cannonballs, that ultimately decided the issue. Three years later, at Castillon, a much larger battery of 150 French guns helped slaughter an English Army led by John Talbot. After Castillon, the English were ready to make peace. The Hundred Years’ War ended, and the age of gunpowder dawned. Longbows would be used well into the 16th century, but gradually firearms would replace them. At Formigny and Castillon, the newly inspired French had avenged Agincourt and put to rest the ghost of Henry V and his vaunted “band of brothers.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments