By Nathan N. Prefer

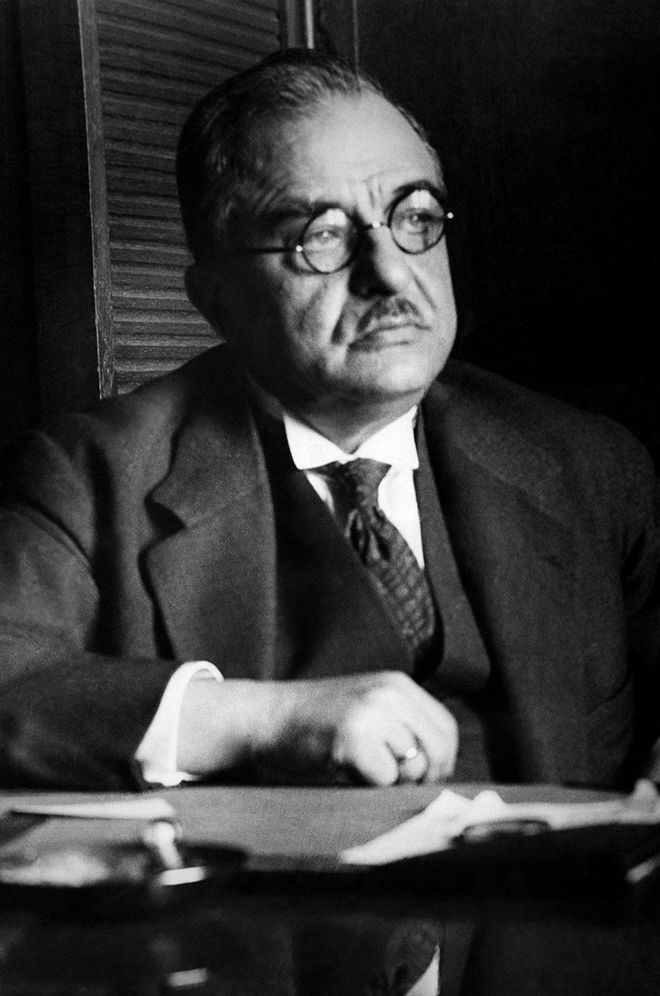

In late 1940 and early 1941, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler was concentrating on his next great conquest, the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, his Axis alliance partner, Benito Mussolini, was having difficulties with his North African campaign against the British and was looking for an “easy” way to restore his and his nation’s prestige.

Mussolini believed that by invading Italy’s old rival Greece, he would challenge British sea power in the Mediterranean and remove the threats to his own supply lines to North Africa. Once strengthened by the Germans in North Africa, he could invade and conquer Egypt, forcing the British out of North Africa altogether. Having easily occupied Albania in 1939, he expected little resistance from the Greeks, whom he believed would not fight.

Mussolini began his program with a demand in August 1940 to the Greek government that it renounce the British guarantee of its independence. Greece’s King George II indignantly refused to do so. Mussolini promptly declared Greece an “unneutral” country secretly sympathetic to Britain and indulging in terror tactics on the Albanian border. The Italian Navy then sank the Greek cruiser Elli while it was anchored in the harbor of the Greek island of Tinos.

On October 15, 1940, the Italian high command held a war council in Rome, and one after another, the generals rose to declare that their forces were ready to crush the insolent Greeks, boldly asserting, “Our troops are eager to fight and advance” and “Enthusiasm is at its highest point.” One participant later said, “They spoke of seizing Greece or Yugoslavia in the same offhand way they would decide to order a cup of coffee.”

After having invaded and easily conquered Greece’s weak neighbor Albania in 1939, the Italians massed their forces along the Greek-Albanian border and waited for an incident that would give them an excuse to invade. One came along soon enough. At 3 am on October 28, 1940, the Italian minister at Athens presented an ultimatum listing Italian “grievances” and giving the Greeks three hours to allow Italian troops to occupy key strategic areas within Greece for the duration of the war.

The reason for Italian optimism was the condition of Greece’s military forces. They had no mechanized equipment, no heavy arms, and only a few hundred antiquated aircraft. Their main line of defense, the Metaxas Line, faced Bulgaria and not Albania, where the Italians had massed their forces.

Luckily, help for the Greeks soon arrived. The British government kept its pledge to ensure Greek independence by mining Greek waters to prevent the Italian Navy from attacking the coastal cities and sent 56,000 British, Australian, and New Zealand troops directly to Greece from North Africa. But the Italians didn’t wait for German help to arrive. Even before the three-hour ultimatum expired, Italian troops had crossed the border into Greece.

Italian optimism quickly evaporated. Within days, the attackers became bogged down in the mountainous and wooded terrain. The Greek commander and “Premier for Life,” General Ioannis Metaxas, shrewdly waited until the Italian forces were deep within the narrow valleys of northern Greece and away from their supply lines before striking.

When the time was right, he unleashed his experienced mountain warriors, known as the Evzones, who hit the Italians with artillery and cut their columns to pieces. British planes then arrived and destroyed much of the Italian supply lines. The 25 Italian divisions committed to the conquest of Greece were stymied.

The Italians, whose officers had claimed that their troops were “eager” and “enthusiastic,” were now demoralized and disheartened. Bad weather in the Greek-Albanian mountains added to their woes. At the end of November 1940, the main Italian force broke and ran, retreating in disorder from the Greek front. General Metaxas quickly took advantage of the Italian discomfiture and moved across the Albanian border, seizing Ersek and cutting the enemy’s lines of communication. By the end of the year, the Greeks had seized one fourth of Albania.

Mussolini’s embarrassments were not yet over. In March 1941, the Italian fleet put to sea to disrupt the flow of British reinforcements pouring into Greece from North Africa. On the night of March 28, a Royal Navy fleet sailed from the port of Alexandria, Egypt, to intercept and sink three Italian cruisers and two destroyers, a savage blow to the Italian Navy’s morale.

Early in 1941, Benito Mussolini was in deeper trouble than he had been at the beginning of the year. The defeat in Greece and the invasion of Albania had stunned the Italian people. Fed a constant diet of lies and propaganda about the invincibility of Italy’s armed forces, they were shocked by these defeats. Not one to admit defeat, Mussolini told his people, “We’ll break the backs of the Greeks, and we don’t need any help!” He ordered mass attacks against the Greek positions, and his troops were slaughtered.

Adolf Hitler, who had not been consulted before the invasion, was annoyed and concerned about the events in Greece and Albania. He was deep into planning his conquest of the Soviet Union and wanted no hostile powers on his flanks as he roared across the Russian steppes. Nor did he want any enemy planes close enough to bomb his precious oil reserves at Ploesti, Romania. Bulgaria had surrendered to his threats and allied itself with Germany, but Yugoslavia and Greece remained fiercely independent. His faith in his Italian ally having waned, he ordered his own armed forces into the battle for Greece.

On April 6, 1941, German forces invaded Yugoslavia. That nation surrendered 11 days later, having been crushed by the German blitzkrieg. At the same time, German forces positioned in Bulgaria struck Greece. They outflanked the Metaxas Line, surrounded three Greek divisions, and captured Thessaloniki in two days. Other German forces struck the Greek homeland from Bulgaria and Albania, a thrust the Greeks were unable to stop.

One after another, the Greek divisions were cut up, flung back into the mountains, and ordered by their leaders to scatter. Although the Greek rear guards were still holding the Italians and even counter attacking them, the main battle along the Greek-Albanian border was lost. After General Metaxas died in January, General Alexander Papagos, the Greek minister of war, assumed command. On April 20, he asked the Germans for a cease-fire, admitting that the Greek Army could no longer successfully resist Germany’s half million well-armed, motorized troops.

Nor could the British, who had come to assist Greece. A withdrawal was ordered, and in yet one more Dunkirk-style operation, the British managed to evacuate about 43,000 troops to Crete and back to North Africa. The cost to the Germans was about 5,000 soldiers. So ended the Greek campaign.

Hitler was magnanimous, however. He maintained the fiction that the Italian armed forces had been the center of the Greek conquest and let Mussolini occupy the country while he turned his own forces east. But many students of the war note that the five weeks the Germans lost in conquering Greece delayed their invasion of Russia long enough to prevent the seizure of Moscow in the first year of that campaign.

Greece was now an occupied country, split between the Germans, Italians, and Bulgarians. The minister of war, General Alexander Papagos, was taken as a hostage to Germany, where he was imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp. (He would be freed in 1945 by American troops.) The Greek king and his government had taken refuge in Cairo, forfeiting all of their authority over the nation. Greece itself was to be administered as an occupied zone by German military authorities, presenting as it did access to the Third Reich’s enemies in the Mediterranean. A group of collaborationist generals ruled the country at the German military’s behest.

General Georgios Tsolakoglou, who had signed the armistice with the Germans, was appointed as prime minister of the new Nazi puppet collaborationist regime in Athens. He was soon succeeded by two others, one of whom, Ioannis Rallis, created the Greek Security Battalions. These units were collaborationist troops who served the puppet regime. Some joined because they shared the German National Socialist agenda, others because they were strongly anti communist, and still others were simply opportunistic. Still others came from Greek fascist organizations that had existed in Greece before the war.

Other Greeks chose to hide in the mountains, refusing to concede their country to the Germans, giving birth to a resistance movement. The movement armed itself with supplies, weapons, and equipment left behind by the British and other supplies hidden by the Greek Army. But even here, there was a dichotomy. Two distinct groups emerged within the resistance. There were the noncommunist partisans—the EDES (The National Republican Greek League)—and there was the communist resistance—the ELAS (Greek People’s Army of Liberation). There were also fringe groups, such as the EAM (National Liberation Front), under a Colonel Psaros.

The first resistance act occurred on the day Athens surrendered on April 27. When the Germans ordered one of the Evzones, Konstandinos Koukidis, to haul down the Greek flag and turn it over to them, the soldier did as he was told, then wrapped the Greek flag around him and jumped to his death from the walls of the ancient fortress. A few days later, two teenagers, Manolis Glezos and Apostolis Santas, tore down the Nazi flag flying from the Acropolis. These acts foreshadowed the Greek resistance movement.

The British continued to try to help. They sent a mission to the resistance to assist in supplying weapons, ammunition, supplies, and medicines via airdrop. They tried to cooperate with all the resistance groups indiscriminately by organizing acts of sabotage that delayed supplies destined for the German Afrika Korps in North Africa.

In one cooperative effort, the Gorgopotamos viaduct on the Athens-Thessaloniki line was blown up on November 25, 1942, causing a great stir among the occupying Axis forces. But such cooperation was rare, and soon the British were forced to sit back and watch the bitter struggle between the resistance groups.

In the mountains of Greece, the resistance movement continued to grow. The EAM was at its largest in the early months. It soon developed its own offshoot, the ELAS, which took to the mountains in the summer of 1942 under the command of Athanasios Klaras, whose nom de guerre was Ares Veloukhiotis; he was a ruthless but capable leader.

Although organized and controlled by the Greek communists, many of the members of ELAS were neither right nor left in the political spectrum: most were Greek patriots who wanted to liberate their country. Soon, the ELAS was reported to have as many as 70,000 members, with the parent organization, EAM, rising to nearly two million by the end of the German occupation.

On the other side of the resistance movement was the EDES, a noncommunist organization under the command of General Napoleon Zervas. In this, like all other resistance groups, women played a key role in operations and support.

Both groups attacked bridges and German supply convoys, which required the Germans and Italians to keep a large occupation force in Greece, further angering Hitler. But as the partisan war progressed, the hatred between the two resistance groups became more and more pronounced, sometimes to the point that they preferred to attack each other than strike at their nation’s occupiers.

While these resistance groups were organizing themselves, the Germans were busy plundering Greece. Having decreed that the Greeks must pay for the war, they confiscated food, animals, and anything of use to the German war effort.

The result was mass starvation and the deaths of an estimated 100,000 Greeks in the first year of the occupation. In part, this was because the new government of collaborationist generals was incompetent and corrupt. Even though crop yields were only about 15 percent below normal, the new government was unable or unwilling to properly organize the collection and distribution of the harvest. While the urban population starved, the rich thrived on a newly rising black market.

The Germans also forced the collaborationist government to grant Germany a “war loan” in addition to reparations. These combined demands resulted in runaway inflation in Greece, which ruined the country’s infrastructure.

Adding to the difficulty was the ongoing argument between the Germans and the Italians regarding who was responsible for providing food for the Greeks. This argument was just one more dispute between the so-called Axis allies that soon led to more deaths. The Germans continued to insist that the Greeks were the Italian Army’s responsibility, and the famine continued to the point that in Athens, the Greek Orthodox rites of burial were abandoned due to the overwhelming number of deaths.

The Greeks blamed the Germans for the famine, while the Italians blamed the British blockade. To address the issue, the British reluctantly agreed to allow shipments of grain from Turkey to pass their blockade. The Greek War Relief Association in the United States also helped by hiring a Turkish ship, the SS Kurtulus, to bring food into Greece from Switzerland and Turkey under Red Cross auspices. These efforts, however, only brought a token level of relief, and in the winter of 1942 the SS Kurtulus ran aground near the Sea of Marmara and was lost.

It wasn’t until 1943 when pressure from the United States, Great Britain itself, and the Vatican convinced the British military to lift the blockade to avoid another year of famine. The situation nonetheless continued to be serious on some of the outlying Greek islands, where the Germans had banned fishing. Without the food and income from fishing, and with no food coming from the mainland, the islanders’ suffering continued. Later, it was determined that this crisis caused the Greek people to lose faith in their government, now believing that the politicians were only interested in taking care of themselves, a deep sense of popular alienation from the Greek state that would last into the next century.

The Greek occupation also produced a strange phenomenon in the German-Italian alliance. Although never truly close allies, the Germans now found themselves drawn more to the Greeks than to their Italian partners. They developed more respect for the Greeks for having defeated the Italians and came to believe that the Greeks were a better-educated people, just like the Germans themselves. In the meantime, the ongoing dispute over who was responsible for the occupation continued.

None of this, however, kept the Germans from enforcing their brutal occupation. After increasing attacks by Greek resistance forces, the Germans resorted to their usual methods of retaliation: wholesale slaughter of the civilian population.

The troops of Lt. Gen. Walter Stettner Ritter von Grabenhofen’s 1st Mountain Division (Gebirgsdivision), veterans of the fighting in Poland, France, and Russia, were sent to Greece in mid-1943 to quell the resistance. On August 16, 1943, the division arrived at the village of Kommeno, near where a resistance force had attacked German troops. The entire village, 317 men, women, and children, were executed and the village burned to the ground.

The atrocities continued. In December 1943, 78 German soldiers were ambushed and killed near the village of Kalavryta. In reprisal, a German force marched from Tripolis to Kalavryta, killing every Greek they met along the way. Another German force—Lt. Gen. Karl von Leisure’s 117th Jäger (Light) Division—marched from Aigion, killing 42 Greek men in the village of Kerpini and then burning the village to the ground.

At the village of Zachloros, they murdered another 18 men and tossed their bodies into a nearby well, then burned that village too. The villages of Souvardo and Vrachni suffered as well before the Germans arrived in Kalavryta. Here, the Germans rounded up the entire male population and took them to a nearby field, where the civilians were killed with machine guns. Survivors were shot again. The village was burned, and on the way back, the Germans burned down the monastery of Agia Lavra, killing four monks and the caretaker.

In another episode, German SS troops killed 218 Greeks in the village of Distomo on June 10, 1944, using bayonets against babies, raping and stabbing pregnant women, and beheading the village priest before moving on. All the men were shot or hanged.

The Bulgarian occupation zone encompassed the whole of northeastern Greece east of the Strymon River in eastern Macedonia and western Thrace. Only the area around the Evros Prefecture, which bordered Turkey, was occupied by the Germans. Even more brutal than their German allies, the Bulgarians adopted a policy of extermination or expulsion, for they wanted to annex those territories to their own country.

Once they arrived in their zone, the Bulgarians deported all Greek mayors, judges, lawyers, and police. Greek schools were closed, and the teachers expelled. Greek clergymen were replaced by Bulgarian priests. The Greek language was sharply repressed. The names of towns and place names were changed to traditional Bulgarian names. Even gravestones with Greek inscriptions were defaced.

The Bulgarians instituted forced labor and put thousands of Greeks out of work by requiring a license to work in any trade or profession, effectively banning Greeks from participating. By the end of 1941, more than 100,000 Greeks had been expelled from the Bulgarian occupation zone and thousands of Bulgarian colonists were brought in to settle the nearly vacant territory, encouraged by cheap confiscated Greek houses and land.

But as elsewhere, the Greeks did not sit idly by while they were being eliminated. In the city of Drama in Macedonia, a revolt erupted on September 28, 1941, and soon spread to other towns. Armed clashes with the occupying forces broke out.

The Bulgarians reacted swiftly and moved troops into the towns to seize all men between the ages of 18 and 45, executing more than 3,000 in Drama alone. In the ensuing pacification campaign, an estimated 15,000 Greeks were killed and dozens of villages looted by the Bulgarian occupiers.

The Italian occupation zone, mainly the bulk of the Greek mainland and most of the offshore islands, fared better, at least at first. Although the Italians had brought up the prospect of annexing part of Greece to Italy, nothing came of the idea due to the opposition of both King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Germans themselves, who feared further alienating the Greeks.

Still, the Italians replaced the Greek civil authorities, particularly on the islands, in the expectation of a postwar annexation. To appease the Albanian claims, an Albanian high commissioner was appointed to oversee some areas claimed by that nation, but again, German opposition kept any real authority to a minimum.

Unlike their German and Bulgarian allies, the Italians never instituted a policy of mass reprisals. They even protected the Greek Jews in their zone. But because they occupied most of Greece, the Italians faced the bulk of the Greek resistance movement’s activities.

By mid-1943, these resistance attacks had driven Italian forces out of some local areas and towns, creating liberated areas known as “Free Greece.” But all this ceased when Italy deposed Mussolini and surrendered to the Allies in July 1943 in an unsuccessful attempt to stave off invasion, moving the Germans to take over the Italian occupation zone in Greece.

Still, postwar estimates show that, at the very least, the Germans executed 21,000 Greeks, the Bulgarians 40,000, and the Italians 9,000 during the occupation.

Things in Greece were already in desperate straits when September 1943 arrived. Early that month, the Allies invaded Italy and the Italian government joined the Western Allies in the war against Germany. This made the Italians the enemy of Nazi Germany. As always, the Germans reacted swiftly, surrounding and disarming their former Italian allies across Greece. Some Italian units fought back, and these were attacked and destroyed, their weapons and supplies confiscated. In some cases, particularly on the outlying islands, Italian officers who had either surrendered or been captured were executed. The Germans moved in to occupy the former Italian zone.

Jewish communities had existed in Greece for thousands of years. There were two main groups, the Romaniote Jews, who had been there since the Roman era, and the 50,000-strong Sephardic Jewish community of Thessaloniki, which originated when Jews fled the Spanish Inquisition during the late Middle Ages.

More than 12,000 Jews served in the Greek armed forces during the war, with 631 being killed in action and another 1,412 permanently disabled. As they did elsewhere, the German and Bulgarian occupiers gradually imposed a series of decrees limiting Jewish participation in public life.

The first deportations to the death camps came when the Bulgarians agreed to German requests to be allowed to round up all 11,000 Jews then living in Macedonia and Thrace. This occurred in 1941, with 20 trains hauling men, women, children, invalids, and the aged north to so-called “labor camps.”

Packed densely into the trains, the Jews had no sanitary arrangements, no food, and no water for the six-day journey. Each morning, the trains would stop, and the dead would be unceremoniously thrown into the snow, with no burial arrangements allowed. All Jewish property was confiscated and sold. Monies not confiscated by the Germans were deposited in a bank account supposedly for the benefit of the deported Jews, most of whom were already dead by the time the deposit statements were printed.

But in the Italian zone, things were different. Mussolini, for all his faults, had refused to use his own resources to pursue Hitler’s “Final Solution,” the elimination of European Jewry.

Many German leaders, including German Foreign Minister Joachim Ribbentrop, complained personally to Mussolini about this lack of enthusiasm but to no avail. In Greece, this aided the Jewish community, for those within the Italian zone were not required to wear the yellow star denoting being a Jew, nor were any special restrictions placed upon them in the Italian zone. In fact, once it became clear that the Germans would continue to persecute the Jews in their zone, many Jews moved into the Italian zone to survive.

The Germans asked the Italians to seal off their zone to Jews, but General Carlo Geloso refused, saying he had no such instructions from his own government. To avoid losing the bulk of the Greek Jews in their midst, the Germans expedited their roundup of Jews in their zone before they could “get away” into the Italian zone. Within five months, they had eliminated Thessaloniki’s Jewish community, the largest group of Sephardic Jewry in the world. An estimated 43,000 Greek Jews perished in this operation.

So weak and undernourished were the Jews deported from Thessaloniki that literally none were spared by the Germans for forced labor. Indeed, so ravaged were these Greek citizens that for three weeks, the crematoria at Auschwitz had to be stopped because of raging spotted typhus brought into the camp by the Greek Jews. Only about 1,000 Jews of Thessaloniki were spared, thanks to the efforts of the Italian consul general in Thessaloniki and the Spanish chargé d’affaires in Athens.

Italian Consul General Castrucci also handed out naturalization papers to Greek Jews, saving 550 (mostly women) from the death camps. Hundreds more were saved by the intervention of Spain, which claimed that they were of Spanish descent and thereby Spanish citizens. German Colonel Adolf Eichmann protested, but Spain persisted, and as Spain was at the time a “friendly” neutral, the matter was dropped.

In Athens, the grand rabbi of the city, Elian Barzilai, was ordered to hand over a complete list of Jewish residents of the city. Instead, he destroyed the list and began to advise the Athenian Jews to flee the city or go into hiding. Some time later, the rabbi himself was spirited away by EAM-ELAS fighters and joined the resistance. Indeed, the resistance helped many Jews escape to the mountains, where they joined the existing resistance groups or formed their own.

Not all the rest of the Jews were rounded up. Many soon learned what it meant to be sent “east” and, heeding Rabbi Barzilai’s warning, fled to the mountains. Here, many, including young Jewish women, served with the resistance. Many left their families behind and would never see them again. Jewish girls who escaped to the mountains served in several ways that belied their somewhat genteel urban upbringing and high level of education. They came from a patriarchal society that protected its women from some of the harsh realities of real public life, yet they soon adapted to the ways of the Greek resistance.

Matilda Bourla had been interested in nursing after seeing a movie about Florence Nightingale and was training as a nurse in Athens. Soon after the German occupation of the Italian zone began, she went into the mountains to serve as a nurse for the resistance. When German patrols came too close to the hospital, the nurses moved the patients higher up or deeper into the mountains. Each nurse carried a wounded man on her back for hours until safety was reached.

Fanny (Flora) Florentin served with the Greek Red Cross in Albania and, in March 1943, escaped into the mountains with her husband. There, she served as a nurse and taught other Greek girls nursing. In the fall of 1944, German troops attacked the resistance group she was aiding, but rather than leave a wounded resistance leader behind, she remained with him and was captured.

The resistance leader killed himself rather than be captured, but Fanny was taken to jail in Ioannina, where she freely admitted she was a Greek Jew. She was imprisoned at the Pavlos Melos Prison in Thessaloniki. While there, she managed to communicate with her sister, and the resistance soon arranged to bribe guards to free Fanny.

There were many others. Dora Bourla fought in the mountains of Macedonia and was known as “Tarzan” by her fellow resistance fighters. One resistance unit consisted of 30 Jewish women. Sara Yehoshus, known as Sarika, was 14 years old when she became a nurse on the island of Euboea, where wounded soldiers and amputees from the Albanian front were sent.

In 1943, she and her mother escaped a German roundup of Jews and fled into the mountains. There, she taught in a village until the Germans came and burned it to the ground for harboring Jews. She escaped higher into the mountains, where she joined another resistance group. When they decided to form a women’s unit, Sarika was chosen as the leader and recruited a dozen of the girls she had previously taught. They would function as a diversionary unit, using Molotov cocktails against outlying German posts to draw off the main German forces from the real resistance targets.

With the Italian surrender in September 1943, the 13,000 Jews under their control lost the protection of that government. They and the Jews in Albania, Montenegro, and the Dodecanese Islands were now at the mercy of the Germans. The anti-Jewish laws were quickly enforced, something the Italians had ignored. German patrols searched day and night for Greek Jews and offered rewards for anyone turning one in.

On September 27, barely three weeks after the Italian surrender, German General Jürgen Stroop, who had recently been in command of the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, arrived in Athens and began to round up any remaining Jews.

An attempt by Jewish resistance fighters to evacuate most of the remaining 3,500 Jews failed, although a few hundred Athenian Jews did escape to the mountains. Jewish leaders managed to destroy all records identifying Jews, which allowed some Jews to remain in hiding; some Greeks hid their Jewish neighbors until the war’s end.

Still, by April and June 1944, half of the Jewish population of Athens had perished. So too did the Jewish populations of the islands of Kastoria, Ioannia, Arta, Corfu, Preveza, and Kana. But the 275 Greek Jews on the island of Zakynthos were hidden deep in the mountains by the island’s population and survived the war.

In a complete waste of their resources, the Germans devoted tanks and trucks urgently needed on the front lines to the roundup of all remaining Jews in Greece outside Athens, which resulted in the deportation of more than 5,000. The entire Jewish population of Rhodes—1,200 people—was deported. So were the 1,800 Jews of Corfu and 260 from Crete. All this at a time when the Germans were retreating on all fronts and losing men, equipment, and supplies at an unsustainable rate. Of the estimated 60,000 Greek Jews at the beginning of the war, only 1,475 survived.

But the Greek Jews had one more contribution to make. At the infamous death camp at Auschwitz, the entire crematoria labor group was made up of 135 Greek Jews led by a former Greek Army officer, Lt. Col. Joseph Baruch, aided by two other officers, José Levy and Maurice Aron.

These three men decided on a plot to destroy the crematoria and stop the mass murder. Secretly assembling dynamite and weapons from German warehouses within the camp, the group, aided by fellow French and Hungarian Jewish inmates, struck on September 6, 1944. Two of the four crematoria were blown up, and the group fought off German guards for over an hour, killing four German officers and 12 German soldiers before they themselves died.

The few Jews who had survived the holocaust in Greece and returned after the war were disappointed. Athens had changed beyond recognition. The Jewish cemetery had been bulldozed, as had the former Jewish neighborhoods The Germans had dynamited all the synagogues. Jewish businesses, as well as former Jewish homes, had been turned over to Greeks, and few would be returned.

In June 1943, a massive demonstration had taken place in Athens protesting the collaborationist regime and the execution of 100 Greeks as reprisal for the sabotaging of a train taking prisoners to the concentration camps. That August, German troops were ordered, “All armed men are to be shot on the spot. Villages from where shots have been fired or where armed men have been encountered are to be destroyed, and the men of the village are to be shot. Elsewhere, all men capable of bearing arms are to be rounded up and sent to Ioaninna.”

Simply put, the Germans henceforth would regard all civilians as the enemy, and no attack on Germans would go unpunished. If the attackers could not be found, then the nearest village would suffer the consequences. The important people of that village—doctors, priests, mayors, and other prominent citizens—would be publicly executed. For every German soldier killed or wounded, 100 Greek civilians were to be executed.

This policy had some effect on the ongoing resistance efforts. EDES and ELAS had become more concerned with fighting a civil war among themselves than fighting the Nazis, and some villages were fearful of helping either side. The attacks against the Germans nevertheless continued, and more and more Greeks joined the resistance.

This German reprisal policy was, as one can imagine, counterproductive. Survivors of these village burnings had no home to return to, and so the Greeks were left with only one option: join the resistance. Also, the Germans were clearly defeated on all battlefronts by August 1944. Russian troops were in Romania and storming into the Balkans, and Greece would be next. The German armies in Greece were in danger of being cut off from Germany.

Finally, the German swastika came down off the Acropolis, and German forces began to evacuate the country they had devastated. The blue and white Greek flag reappeared on buildings and homes, and Athens rejoiced with public demonstrations, but it was not over just yet.

More than 500,000 Greeks, mostly civilians, had died in World War II. The Jewish communities in Greece ceased to exist. A loaf of bread in Athens cost two million drachmas, and people were trading homes and property for olive oil to keep their children alive.

When the Allies arrived on the heels of the retreating Germans, they found a people who stared, dazed in a state of shock, over what they had been through: schools burned to the ground, more than 1,770 villages destroyed, thousands of Greek civilians homeless. There were no surviving industries or factories. Ports and cities were in ruins. There was no government. The economy was bankrupt, the infrastructure destroyed.

Sixty percent of the horses, mules, and cattle had been slaughtered for no reason. Twenty-five percent of the country’s forests had been decimated, and 56 percent of the roads were in need of urgent repair. Ninety percent of the bridges had been destroyed, and nearly all the water and sewage facilities were in ruins. The entire country needed to be rebuilt. Thirteen percent of the Greek population—one of every 10 Greeks—was dead. But there was still fighting to be done.

The Germans left behind the Greek anti communist and fascist security battalions under the control of the collaborationist government, and they busily hunted down communists and battled the ELAS resistance groups in the countryside. A civil war was about to begin.

No Greek leader with the stature of Yugoslavian partisan leader Marshal Josef Broz Tito had emerged from the Greek resistance movements. Greece, both within and without, was in political turmoil. In North Africa, the “Free Greek” forces serving King George II had mutinied no less than three times, demanding a republican government.

In response, King George II agreed to abide by a national plebiscite on Greece’s future once the Germans were defeated. Political turmoil continued, though, with each side demanding concessions from the others while refusing to concede anything themselves.

Moderated by the British, who had the principal interests in the Mediterranean, the various Greek factions eventually came to blows. The communist organizations refused to disarm when the provisional Greek government returned to Athens with the incoming British troops. The first battle began in Athens on December 3, 1944, even as World War II continued elsewhere.

Often called the first battle of the Cold War, the Greek Civil War was an international war, with the Greek government’s army supplied and advised by the United States under the terms of the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan. The communist forces were equally supplied and advised by Soviet proxies in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Albania. The scattered clashes of 1943 turned into full-scale civil warfare between the two groups.

A truce agreement was entered on February 12, 1945, after a 33-day battle in Athens. But tensions remained, with many leftist organizations hiding weapons and the “White Terror” of the right against the left within Greece. These tensions once again erupted into open warfare, and in December 1947, the communists formed a provisional Greek government. The civil war would rage across Greece until 1949, when the Greek communists surrendered after their allies had abandoned them.

This ended armed conflict in Greece for the time being, but as later events would show, it was only the beginning of internal political struggles that would take decades to resolve.

Nathan Prefer is the author of several books of World War II history and is a frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly. He lives in Fort Myers, Florida.

It’s an horrific story. Another nail in the coffin for the myth of the ‘clean Wehrmacht’.

One small point (although a very minor issue in relation to this story): King George first evacuated Greece to Crete. When Crete was invaded by the Germans (another ignominious chapter in the early history of Britain/Empire forces in the war), he again fled, this time to Egypt, before moving to Britain.

The German military was little better than ruthless barbarians.