By David H. Lippman

Amid rain, lightning, and dark, the British admiral and American general picked their way through choppy seas to the transport USS McCawley, off the coast of Guadalcanal. Maj. Gen. Archibald Vandegrift of the U.S. Marine Corps was exhausted. Britain’s Rear Admiral Victor Alexander Crutchley, commanding the Allied Screening Force, an Australian-American mix of six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and eight destroyers, looked “ready to pass out.”

So did the senior officer on McCawley they were going to see, Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, who commanded the American amphibious assault forces that were riding waves off the invaded islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi that evening.

There was good reason for all three men to be fatigued. In the three days since they had led the invasion, none had been able to sleep. Now the three officers were losing their carrier-based air cover, and the transports would have to pull out without fully unloading their supplies. This was a grave issue, but their crisis was about to become far worse—in minutes, they would be helpless spectators to the greatest defeat at sea in the history of the United States and Royal Australian Navies.

Operation Watchtower was the first Allied Pacific offensive of World War II. In early 1942, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King was determined to drive the Japanese north through the Solomon Islands chain and up that jungle road to Tokyo.

The task was given to Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, and the plan called for an invasion of two islands in the Solomons, the capital at Tulagi and Guadalcanal, a larger island south of Tulagi. Between them sat Savo Island, a dead volcano.

The assault was assigned to the 1st Marine Division under Vandegrift. Turner would command the invasion force of transports. The assault’s air cover would come from Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s three carriers, and its close-in defense and gunnery support from Crutchley’s group. It was the first offensive mix of British, Australian, and American naval forces in battle.

Planned for September, the invasion was moved up to August 1 because the Japanese were building a runway for land-based planes on Guadalcanal. The base was a clear threat to American communications with Australia and New Zealand. Watchtower moved into high gear. Delays pushed the assault back to August 7.

Meanwhile, the invasion’s leaders met on Fletcher’s flagship, the carrier Saratoga, at Koro on July 26. There Fletcher outlined his plans. The carrier force would stay south of Guadalcanal. Turner would take the transports in with the cruisers and destroyers to protect him, under Crutchley. Fletcher then dropped his bombshell: he would withdraw his three carriers 48 hours after the invasion.

Turner was outraged. Withdrawing the air cover would jeopardize the operation. It would take longer than that to unload all the supplies. Vandegrift agreed. But Fletcher was firm. As fleet commander at the carrier battles of Coral Sea and Midway, two of his carriers had been sunk beneath his feet.

The whole force headed for Guadalcanal and Tulagi on July 31, and Crutchley finally had a chance to operate with his cruisers and destroyers. Some he knew already. The British-built County-class heavy cruisers HMAS Australia and HMAS Canberra had worked with the American heavy cruiser USS Chicago for some months, directly under his command.

But the new cruisers assigned to him, USS Vincennes, Quincy, and Astoria, had not. More importantly, despite long traditions of valor, professionalism, and ingenuity, the U.S. Navy did not actually have standard operating procedures for surface naval battles. Except for disastrous actions in the Java Sea under Dutch command in February 1942, the U.S. Navy had not fought a surface battle since 1898, and that against a decrepit Spanish Navy. U.S. Navy task group commanders were expected to determine their procedures on the spot, which could lead to difficulties with tactical communication and coordination.

But at least the force could count on solid leadership. Aged 48, Crutchley was a veteran sea dog with an immense red beard, holder of a Victoria Cross from World War I, and had fought surface actions in World War II.

As the Allied force steamed north, Crutchley worked out his tactical plans in his cabin on Australia. He was reluctant to put his complex and poorly coordinated force into a single unit, fearing it would come apart in the stress of battle. Later battles would prove him right—the Americans would try that tactic in four major naval engagements in the Solomons and take harsh losses.

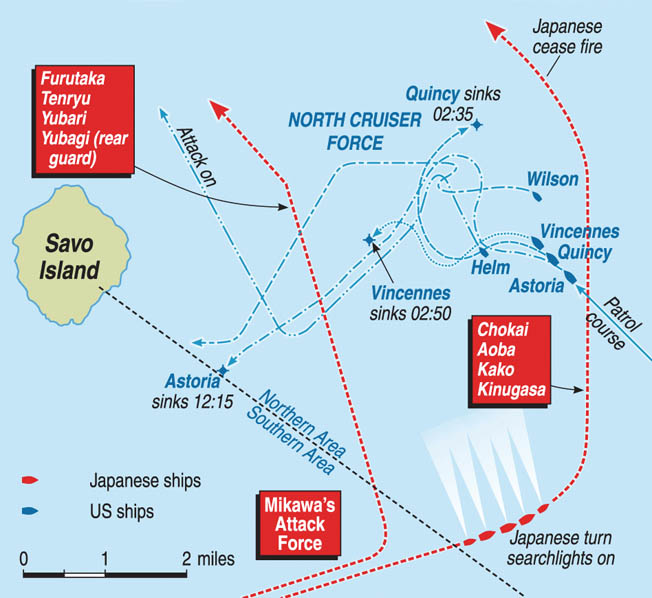

Instead, he chose to divide his force. His own group, used to working together, would guard the southern approach to Guadalcanal up to Savo Island as the Southern Group, while the three American cruisers would patrol the area between Savo and Tulagi. The Northern Group would be headed by the senior American officer, Vincennes’ skipper Captain Frederick “Fearless Freddie” Riefkohl. Each group would have three heavy cruisers and two destroyers.

To the east, Crutchley posted his light cruisers, USS San Juan and HMAS Hobart, to guard against a flanking move. And finally, he intended to put two destroyers on outpost duty, USS Blue and USS Ralph Talbot, which would head out before sunset and patrol, Ralph Talbot northwest of Savo, Blue southwest of Savo, all night long. They had the best radar capability of all his destroyers, a range of seven to 10 miles.

Turner approved Crutchley’s plans, and on the night of Friday, August 7, the invasion force steamed from the west into what would soon be named Ironbottom Sound between Guadalcanal and Tulagi. At 6:50 am, the Marines stormed ashore.

There was no resistance on Guadalcanal. On Tulagi and its nearby islands, the Marines ran into determined defense, with Japanese troops radioing their headquarters in Rabaul, on the island of New Britain, for help.

The messages reached Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, who commanded the Japanese Eighth Fleet. He commanded the surface warship punch in the area from his flagship, the heavy cruiser Chokai, and the four warships of Cruiser Division Six assigned to him: Aoba, Kinugasa, Furutaka, and Kako. Backing them up were the two light cruisers Tenryu and Yubari, and a single destroyer, Yunagi.

Mikawa ordered seaplane tenders and supply ships loaded with reinforcements for Guadalcanal, fighters and bombers to fly 600 miles from Rabaul to Guadalcanal to attack the enemy ships, and his own scattered warships to assemble at Rabaul for a swift counterattack. He intended to hurl his five heavy and two light cruisers in one coiled fist, making a night attack on the enemy to destroy their fleet and transports.

The plan seemed foolhardy. The Americans had air superiority and plenty of reconnaissance planes to spot and track Mikawa’s force, so it would not have the advantage of surprise. It would have a limited amount of time to get into the Guadalcanal area by night and a limited amount of time to get back out. The American warships had radar to control their guns, a major advantage in night fighting.

But Mikawa and his men were unperturbed. The Imperial Japanese Navy trained hard for night battles. The Japanese may have lacked radar, but they trained the most skilled lookouts to serve by night. They could spot targets as far as four miles—8,000 meters—away, even on dark nights. Their searchlights were superior to the American equipment.

Most importantly, unlike their American opponents, Japanese heavy cruisers were armed with torpedoes, in as many as eight tubes, the greatest in the world. Japan’s oxygen-fueled Long Lance torpedo was 24 inches in diameter, had a speed of 50 knots, a range of nearly four miles, and exploded on impact with the power of its 1,210-pound warhead. By comparison, the Americans regarded the idea of arming their heavy cruisers with torpedoes as obsolete and did not do so.

At 4:30 pm on August 7, Mikawa led his task force to sea to fight the enemy in the best samurai tradition. Mikawa’s force steamed down the gaps between the Solomon Islands chain—a route that would later be called The Slot—without interference, spotted by passing Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of General Douglas MacArthur’s command in Australia. The American planes reported “six unidentified ships sighted,” but no more—no position, course, or speed.

Meanwhile, Japanese bombers attacked the American ships, putting a bomb into the destroyer Mugford, resulting in minor damage and killing 22 men.

That afternoon, Mikawa told his staff that his plan was a run-in by night, followed by a torpedo attack. He would take his chances with being spotted by day during the race down on the 8th.

On the Allied side, Crutchley’s ships went to their positions, and everything was quiet, the ships steaming back and forth—the Southern Force in a straight line, the Northern Force in a box patrol.

The next morning, August 8, Mikawa launched his seaplanes to check out Guadalcanal, and more Japanese bombers headed for the island.

When the raid came in at noon, the bombers were greeted by a massive barrage. The Japanese hit the destroyer Jarvis and a bomber crashed into the transport George F. Elliott, setting off a fire that soon raged out of control. The transport was abandoned. The destroyer Hull tried to sink it with four torpedoes and that failed. The George F. Elliott lay abandoned and smoking all through the night.

Meanwhile, the Japanese ships steamed southward, through sticky tropical heat, unhampered but spotted. The American submarine S-38 reported them, as did land-based coastwatchers, but the major report was made by a Royal Australian Air Force Lockheed Hudson patrol bomber flown by Sergeant Will Stutt. He tried to radio in his sighting, but his radio failed, so he flew back to his base at Milne Bay, which took two hours and 16 minutes. He immediately made his report at 12:42 pm, but that vital—and ambiguous—message did not get to Crutchley until 6:17 pm.

All the warning messages were delayed or mishandled—some went through Pearl Harbor, others through MacArthur’s command, and McCawley’s radio room could not even monitor the coastwatchers’ network. The unified communications nets of later invasions had not been developed yet.

But it all seemed academic as long as Fletcher’s carriers were standing southeast of Guadalcanal. If the Japanese tried to attack by night, they would be caught coming and going by the carrier planes.

The bombshell hit when Fletcher radioed Ghormley at 6:07 pm: “Total fighter strength reduced from 99 to 78. In view of large numbers of enemy torpedo and bomber planes in area recommend immediate withdrawal of carriers. Request you send tankers immediately to rendezvous decided by you as fuel running low.”

By the time Fletcher sent this message, he was heading south to fuel, so the recommendation was an order. Worse, his two issues were not true. He had 83 fighters—more than at Midway—and his warships were not low on fuel. Historians would later heap fury upon Fletcher’s decision, some calling it “cowardice.”

Nonetheless, with the air cover departing, Turner’s transports—still unloading—would be open to Japanese attack. They would have to flee Guadalcanal. Turner summoned his two commanders to his flagship at 8 pm.

Mikawa’s ships, however, were still plunging southward. At 7:15 pm, Mikawa signaled his ships and men: “Let us attack with certain victory in the traditional night attack of the Imperial Japanese Navy. May each one calmly do his utmost.”

At 8:30, an exhausted Crutchley was summoned to the powwow on McCawley. He had barely slept for three days, taking short catnaps on his flag bridge. He ordered the senior skipper of the Southern Force, USS Chicago’s Captain Howard Bode, to take charge, saying, “I may or may not be back later,” and steamed off on Australia into the dark at 9:23 pm.

Oddly, Crutchley did not let Riefkohl on Vincennes, commanding the Northern Force, know he was leaving, although he did send a generic radio message to his nearby ships to that effect.

Nobody seemed alert that evening. The Japanese shot off last-minute reconnaissance seaplanes from their heavy cruisers, and they zoomed over the two Allied forces. Incredibly, the defenders assumed they were American planes, even when they dispensed flares to illuminate the scene. All five skippers—Frank Getting on Canberra, William G. Greenman on Astoria, Riefkohl on Vincennes, Bode on Chicago, and Samuel N. Moore of Quincy—hit the sack. Nor did Bode, as temporary boss of the Southern Force, put Chicago in line ahead of Canberra. He figured that such maneuvering in the dark, with submarines possibly about, would be dangerous. He stayed second in line.

At the 10:30 pm conference, the three leaders faced facts—Turner’s transports would have to withdraw in the morning, leaving the Marines short on supplies. When the meeting broke up before midnight, it took Crutchley an hour to return to Australia, and he saw the flares. He figured that meant a Japanese submarine attack, so he decided to stay with Turner’s screen until dawn. So now nobody was awake and in command in the battle area.

But on the other side, Mikawa was in command, and his force was on the final portion of its sprint, passing Savo at 12:40 am. Three minutes later, Chokai lookouts spotted a ship headed toward them from the starboard side, five miles away. Mikawa adjusted course away from the intruder—the watchdog Blue—and incredibly the destroyer did a 180-degree turn, having neither spotted the Japanese with radar or lookouts. Then another scare—a ship was just north of Savo, steaming away, which turned out to be an inter-island schooner. Mikawa made another course correction and evaded this ship. Then Mikawa gave his final orders: Yunagi to drop out of formation to keep an eye on Blue and the smoking Jarvis … all engines on 30 knots … torpedoes ready.

At 1:25, Chokai’s lookouts spotted Chicago and Canberra nine miles ahead of them, silhouetted by the burning George F. Elliott. At 1:33 am on Sunday, August 9, Mikawa gave the order, “All ships attack!”

The nearest defending ship was Jarvis, and the Japanese treated her to a dose of torpedoes, which all missed. Jarvis was unable to respond, and Mikawa’s ships raced in on their first major target, the Southern Force. At 1:36, Mikawa yelled, “Independent firing!”

Flares popped from Japanese seaplanes over the force, illuminating them, and the destroyer Patterson spotted the enemy, firing off a radio message: “Warning! Warning! Strange ships entering harbor!”

It was too late. The Japanese cruisers cut loose with their torpedoes, heading straight for Canberra, followed by a barrage of 8-inch shells. Getting raced to his cruiser’s bridge and ordered “Starboard 35” to unmask his guns. But a Japanese shell slammed into the plot room, wrecking it. Another smashed the radio room’s transmitters, and another hit square on the bridge, killing Gunnery Officer Lt. Cmdr. D.M. Hole instantly, mortally wounding Getting, and severely wounding everyone else on the bridge. The next salvo also hit the bridge and slammed into the cruiser’s engine rooms, setting them ablaze and cutting off steam and electrical power. Canberra took on a 10-degree list to starboard. The ship could neither move nor address her damage nor fire her armament.

To add to Canberra’s misery, postwar studies suggested that the critical torpedo hit that punched out her engines did not come from a Japanese ship, but from her escorting destroyer on the starboard side, Bagley, whose jittery captain hurled four torpedoes, one of which apparently slammed into Canberra instead of the Japanese.

Canberra fired only a few shots in her own defense. On the wrecked bridge, the executive officer, Commander J.A. Walsh, took over a dying ship.

The next cruiser was Chicago, and when the flares lit up the night Bode was summoned to the bridge. He arrived just in time to learn of dark objects approaching and ordered star shells to be fired. The bridge lookout reported three wakes in the water, which had to be torpedoes. Two missed Chicago, but at 1:47 am the third tore a hole in her bow, mangling steel plates and peeling back steel. A vast column of water flew into the sky, covering the ship as high as the foretop, and the foremast’s tip crashed onto the radar fire director, putting it out of the game.

Bode tried to fight back, firing 5-inch star shells to illuminate the scene for his 8-inch main battery. The shells failed to ignite, the radar did not spot a target, and Chicago’s guns were silent for the whole battle.

So was her radio. Incredibly, having spotted the enemy, Bode did not send a message to the Northern Force about his group’s disastrous encounter with the enemy.

Nobody with the Northern Force reacted. Crewmen and officers were exhausted … radio messages were only semi-coherent due to atmospherics … lightning and rain squalls were impacting nerves and visibility… and Riefkohl did not know Crutchley had departed. When Japanese seaplanes flew over the force just before the attack, the Americans assumed that they were friendly because they had their running lights on.

At 1:43 am, Vincennes’ radio room received the big message from Patterson about strange ships entering the harbor, but it was not relayed to the bridge. Quincy got it too and passed it to the bridge, but did not tell gunnery. Astoria never received it. Neither did Australia, as she lacked American TBS (Talk Between Ships) radio. The Northern Force cruisers steamed northward at a steady 10 knots, heedless of the disaster that had befallen their sister ships.

Meanwhile, the Japanese headed northeast, straight toward the Northern Force. The Japanese ships broke their neat formation, with Furutaka, Tenryu, and Yubari cutting close to Savo Island, while Chokai and the other three cruisers raced farther east. Why they split up was never clear, but the damage they inflicted was: 17 torpedoes fired in six minutes, only three hits, but enough to wipe out the Southern Force without suffering a single hit. The two columns were now about to strike the American line from both ends at the same time.

Japanese torpedo men reloaded their tubes, and Chokai’s massive searchlights snapped on, illuminating the three American cruisers, guns trained in. Mikawa ordered his ships to open fire at 1:47 am.

On Vincennes, Lt. Cmdr. Miller, the officer of the deck, noted star shells and what appeared to be gunfire to the south and summoned Riefkohl, who had spent the last 21 hours on the bridge. Riefkohl peered into the low clouds through his binoculars and suggested the Southern Force was firing on an enemy destroyer sneaking into the sound. The last thing he wanted to do was fire on his own ships, leave the northern entrance unguarded, or cause chaos, as he lacked direction from Crutchley.

When the Japanese searchlights flew on, Riefkohl assumed they were American lights and told his radiomen to signal them, “Turn those searchlights off of us. We are friendly.” He also rang up speed to 20 knots. Then he waited for word from Crutchley.

On Astoria, supervisor of the watch Lt. Cmdr. J.R. Topper had just completed the ship’s scheduled turn when he felt an underwater explosion nearby, saw the starshells, and yelled for the officer of the deck to summon Greenman.

Meanwhile, Astoria opened fire with a full salvo, on the orders of Gunnery Officer Lt. Cmdr. Truesdell, who saw the flares and responded with one of the few displays of initiative that night, identifying the targets as Japanese “cruisers of the Nachi class!”

Greenman sprinted into the pilothouse and asked, “Who sounded the general alarm? Who gave the order to commence firing?”

Topper said he had not and did not know who had.

“Topper,” Greenman said, “I think we are firing on our own ships. Let’s not get excited and act too hastily. Cease firing.”

Topper agreed with his skipper and passed the word to do so. “What are you firing at?” the bridge talker asked Truesdell.

“Japanese cruisers,” Truesdell yelled back. “Request permission to commence firing.”

The talker made Truesdell sound tougher, saying, “Mr. Truesdell said for God’s sake give the word to resume firing.”

The Japanese opened fire on the American ships, and the bridge crew saw shell splashes short and ahead of them. “Our ships or not, we’ve got to stop them,” said Greenman, still afraid he was shooting at his own ships.

The third salvo on Astoria was 300 yards short, the fourth 200 yards short, but the fifth hit Astoria amidships directly on her two seaplane catapults with their vast store of gasoline, oil, fabric, and wood created by two SOC-3 biplanes, setting off a massive fire. Another shell silenced Turret I. More salvos smashed the bow, gun deck, and bridge, killing the navigator, chief quartermaster, signal officer, and helmsman.

Greenman phoned the engine room and got horrible news … Engineering Officer Lt. Cmdr. Hayes was abandoning the after engine room due to fires overhead, and the boilers could only do eight knots. More Japanese shells were whistling in, tearing Astoria apart. Topper reported hits and smoke all over the ship … Turret I … No. 2 Engine Room … the Marine compartment … the fire main-raisers … a direct hit on No. 1 Fire Room … no water topside to fight the fires … Turrets II and III firing raggedly in local control.

Astoria was suffering an ordeal, but not as dreadful as Quincy. Her supervisor of the watch, Lt. Cmdr. Billings, did not realize the gravity of the situation until Japanese searchlights illuminated his ship as the new officer of the deck, Lieutenant Clarke, was taking over. Clarke sent a quartermaster to awaken Captain Moore and had the ship’s bugler sound general quarters into the public address system.

When Moore reached the bridge, he made a right decision and then a wrong one. The right one was to order his guns to open fire on the enemy searchlights. The wrong one was to order his ship’s recognition lights turned on—he thought the opposing vessels were friendly. His officers did so, but the Japanese simply poured shells into Quincy’s hull, setting the seaplane on the portside catapult ablaze. The fire had the same impact on Quincy as on Astoria.

More shells cascaded down, one tearing through the pilothouse, killing the executive officer, the navigator, the damage control officer, fatally wounding Moore, and shooting off half the side of Billings’ face. Billings staggered to the wing and said, “I’m all right, I’m all right. Keep calm, everything will be all right. The ship will go down fighting.”

Moore yelled, “We are going down the middle. Give them hell!” Then he slumped to the right of the wheel and muttered orders to transfer control to battle station II and that the ship should be beached. It did not matter. Japanese shells shredded Quincy’s hull. Communications, steering, engine power, and guns all soon were out of action.

Assistant Gunnery Officer Andrew climbed up to the bridge for orders to find it strewn with bloodied bodies, and the quartermaster struggling with a useless wheel. “The captain is dead,” the quartermaster said. “He told me to beach the ship, but I can’t steer.” At that moment, Moore tried to rise from the deck, collapsed, and died.

Leadership fell upon Lt. Cmdr. Harry Heneberger, the gunnery officer, who ranked seventh in the chain of command. Once in control, he ordered a full main battery salvo, but the enemy targets had passed astern, and Turrets I and II could not fire until the aft director had the target bearing. Heneberger gave the necessary orders, but Japanese shells hit their targets first, jamming Turret III in train. Heneberger shifted control back to forward, but Japanese shells hit Turret II, which exploded it. Turret I was put out when a shell started a fire in the upper powder room. Quincy was out of action.

Vincennes was still in action, though. But Riefkohl wanted orders from Crutchley, especially a decision on whether to use searchlights to illuminate the Japanese. But Crutchley was not there, and while Riefkohl dithered the Japanese trained their own searchlights on Vincennes. Riefkohl then made the wrong decision. He assumed the light was the Southern Force and sent a blinker message telling the intruders to get their lights off of his ships. The Japanese answered his message with a salvo of armor-piercing shells, which tore apart the armored tube of the conning tower, cutting communications to the bridge. Another shell hit amidships, and like the other three cruisers, set Vincennes’ seaplanes afire.

As Vincennes turned to port to avoid the oncoming Quincy, Japanese torpedoes whacked home into “Vinny Maru’s” hull, hitting her No. 1 and No. 4 Fire Rooms. More Japanese shells slammed into her main steam lines, fire mains, and main battery control. A hit on the aft director blew it right off the Vincennes. The ship was left dead in the water.

It was the same below decks on Quincy, where chief engineer Lt. Cmdr. Eugene E. Elmore clambered down into the engine room, never to be seen again. Ensign Cohen, four years out of Annapolis, was at his general quarters station in No. 1 Mess Hall over the engine room. He heard the blast of shells punching into the adjacent No. 2 Mess Hall, opened a hatch, and saw it ablaze. Then Quincy shook from a torpedo hit. Cohen tried the escape hatch to the well deck above them. It was open, but flames roared in. Both fire and engine rooms filled with smoke and flame.

Below decks on Vincennes there were fewer survivors as the ship took torpedoes right in the engine rooms, two or three from Chokai in No. 4 Fire Room, one from Yubari in No. 1 Fire Room, leaving behind no survivors. A violent explosion hit Vincennes, and she began to list and settle to port.

Quincy continued to suffer. When the port catapult was hit by a Japanese 6-inch shell, the plane exploded and sent flames and shrapnel flying in all directions. Fuel spilled across the deck, bursting into flames. Damage control parties hooked up hoses to hydrants and found no water pressure. The lightly wounded carted off the more seriously wounded and the dead.

With the order given to abandon ship, Quincy sailors found life jackets were securely tied in bundles to keep them out of the way, floater nets were lashed to baskets high up on bulkheads, and rafts were secured atop gun turrets, making them impossible to reach in an emergency. Sailors climbed flaming bulkheads and turrets to free rafts and floater nets.

Her screws still turning, Quincy shuffled toward Tulagi. She sank at 2:55 am, in 500 fathoms, taking 370 officers and men with her to the bottom.

Vincennes’ battle lasted all of 18 minutes. The first shell smacked her at 1:51 am and hit the bridge. The second blasted the carpenter’s shop, the third the hangar deck setting off major fires, and the fourth blasted Batt II, ripping the radio antenna trunks. More shells whistled home, smashing searchlights and battle phones, cutting power to turrets, and rupturing fire mains.

Riefkohl ordered a 20-knot speed and headed left toward his pals in the Southern Force, unaware he was going between two enemy columns of heavy cruisers. Despite the long odds, Vincennes fought back, firing a salvo at Kinugasa. But it was not enough against the barrage. More Japanese shells smashed the “Vinny Maru,” pulverizing her movie locker, searchlight platform, and the forward medical station where Navy surgeon Commander Blackwood, in his 60s, was killed along with his entire medical team. The mess attendant whose jaw he was sewing up ran from the compartment, holding the jaw with his hand, with only a leg scratch.

Riefkohl turned hard right to escape the barrage, calling for 25 knots but only got 19. As Vincennes turned, two torpedoes gored through her port side. A hit in main battery control aft killed the control officer there, and two more shattered Turrets I and II. A steam line burst, and the forward magazines had to be flooded down. Steering power failed in the pilothouse, and control was shifted to steering aft. Riefkohl called for a frantic left turn, but the engine room responded to neither telegraph nor the messenger who was sent down. He never returned.

Just after 2 am, the Japanese fixed their powerful lights on Vincennes and hurled more shells at her, jamming the forward director in train and smashing the machine shop, the forward mess hall, the starboard catapult tower, the well deck, the radar room, and even carrying off the cruiser’s battle ensign.

A Japanese 8-inch shell smashed Turret II, knocking out the last of Vincennes’ guns. The gunnery officer reported to Riefkohl, “Captain, we have absolutely no guns to fire with. Everything is out.”

With that, the Japanese moved off, and Riefkohl turned to the lugubrious task of abandoning ship. The list increased steadily, and the skipper ordered all life rafts over the side and wounded men into life jackets. Two doctors and their corpsmen stood their posts at dressing stations to the end.

At 2:30 am, Riefkohl gave the “abandon ship” order, and he gloomily stared about his ship—now a shambles—then was washed off the deck of his command at 2:40 am. Luckily, he found a raft, and in it was the mess attendant with the busted jaw, still holding it with one hand. The mess attendant ignored his pain to render what help he could.

Vincennes sank around 2:50 am. She had suffered at least 56 large-caliber shell hits and six torpedo hits.

Astoria finally started firing despite failures in powder and shell hoists. Turret III fired only three salvos before losing power. Turret II got off a few shells and was about to fire on a near target to port when all power failed. Good thing, too. She was aiming at Quincy.

With Astoria defenseless, the Japanese gunners shredded her upper works. Most of the shells landed between 2:01 and 2:06 am and then stopped at 2:15. Truesdell emerged from Director I to see nothing but fire. He clambered through fire and bodies to the bridge to tell Greenman he should leave, as the ammunition room over his head was on fire. Greenman headed for the area forward of Turret II on the communications deck and ordered all wounded brought down to the forecastle. Truesdell went to ensure all wounded had been carried off. He reported to Greenman that there was a chance Astoria could be saved.

At 2:25 am, Greenman ordered all hands topside. Hayes made sure everyone got out of his engine rooms—not many did—then passed out. He was carried up above.

Forward, Greenman saw Astoria had a list of three degrees, fires were raging unchecked, fire mains ruptured, and 400 men on the forecastle, 70 of them wounded and many dead. He ordered a bucket brigade, but the fires were too huge. At least the 8-inch magazines had been flooded. If the 5-inch magazines could be flooded from the bucket brigade and a handy-billy pump, disaster could be prevented.

Greenman signaled for the destroyer Bagley to come alongside, and she did so, nudging bow to bow. The ships were lashed together, and Astoria’s men were taken off, Greenman last, at 4:45 am.

While this nightmare was going on, two admirals struggled with the situation. On his flagship Australia, Crutchley could only watch helplessly at the spectacle of lightning, flares, and the flash of gunfire to the west. He wrote later, “I was in complete ignorance of the number or the nature of the enemy force and the progress of the action being fought.”

Crutchley radioed to Riefkohl and Bode to find out what was going on, but got no answer from Vincennes—for obvious reasons, her radio was out of action—and a strange one from Chicago at 2:45 am, which said, “We are now standing toward Lengo on course 100.” Bode had taken Chicago straight ahead. Bode amplified: “Chicago south of Savo Island, hit by torpedo, slightly down by bow. Enemy ships firing to seaward. Canberra burning on bearing 250 five miles south of Savo. Two destroyers stand by Canberra.”

Crutchley reported to Turner: “Surface action near Savo. Situation as yet undetermined.”

With the situation fluid, Crutchley was understandably reluctant to steam to the sound of the guns, not knowing if he would find himself the sole warship amid an enemy task force.

On the opposing side, Mikawa and his task force were rounding the northwestward curve passing out of the action, and the scattered Japanese ships were regrouping and reporting damage to themselves and the enemy. The Americans had not done much damage: a near-miss by Chicago on Tenryu had wounded two men. Kinugasa was hit in the starboard side near the waterline by Patterson, and another shell from Vincennes had damaged the port steering control room with one killed and one wounded. Aoba suffered a hit in a torpedo tube. The only serious damage was suffered on the flagship Chokai. Three 8-inch shells from Quincy had torn open her flag plot, killing 34 men, wounding 48, and burning all the charts. If the shell had landed 15 feet forward, it would have killed Mikawa and his whole staff.

Even so, the admiral was unshaken, probably because the Japanese damage was minor compared to the horror he had inflicted on the Americans. Now he had to make the biggest decision of the night, and that call would result in the biggest mistake of the evening: whether or not to continue east and attack the American transports, still fully loaded with vital supplies.

There was nothing between him and those unarmed freighters but Australia and her six destroyers, and he could brush them aside with ease. The big problem was time. First he would have to regroup his ships, then steam into the transports’ assembly area and spend time shelling the enemy ships.

The longer he stayed off Guadalcanal, the greater the chances of being within range of the American carrier planes after dawn. Without air cover, Mikawa’s proud cruisers—so powerful by night—were sitting ducks under the tropical sun. He decided not to push his incredible luck any further, not knowing that Fletcher had withdrawn his carriers already.

At 2:23 am, Mikawa flashed the order to his ships: “All forces withdraw. Force in line ahead, course 320, speed 30 knots.”

But the battle was not over yet. As Mikawa’s ships steamed back north of Savo Island heading for Rabaul, they spotted the northern American guardship, Ralph Talbot, still pacing back and forth in accordance with her orders. Nobody had summoned her to battle. The Japanese wasted no time, slapping searchlights on her and opening fire at 7,000 yards, the first salvo short.

The tin can’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Joseph Callahan, saw the green dye splashes and, like everyone else that night, thought they were friendly shells. He lit his masthead recognition lights and yelled on TBS, “You are firing on Jimmy. You are firing on Jimmy.”

Yubari obligingly answered “Jimmy” with more shells, and two of them hit Ralph Talbot, blasting the No. 1 torpedo tube and wardroom, killing the doctor, Lieutenant E.N. Kveton, and a patient he was treating. The shell set the compartment ablaze.

Callahan fired four torpedoes back at the Japanese, and all missed. Another Japanese shell hit Ralph Talbot’s No. 4 5-inch gun mount, blasting the crew. More shells struck Ralph Talbot below the waterline, and Callahan drove his ship into a rain squall and out of the fight, which saved her. Mikawa’s force raced past Ralph Talbot into the dark, shuffling into antiaircraft formation to face the dawn, headed for Rabaul, safety, and glory.

Meanwhile, about 1,000 U.S. and Australian sailors floated in the water in various stages of shock, exhaustion, injury, and wounding. Some 600 sailors were grouped around the pall of smoke over Quincy’s grave, and Lt. Cmdr. Andrew assembled a collection of rafts and nets and about 100 men, including Ensign Cohen, who kept jumping from the nets to swim into the night to save a man in trouble.

Around Vincennes the scene was the same, but Astoria still floated despite the display of ammunition cooking off. Men in the water from all three ships worried that the exploding ordnance would kill them, too.

The destroyer Ellet reached the Quincy crews and began taking them aboard, many grievously wounded.

Vincennes’ survivors were picked up by Mugford and Helm. At 8:30 am, Riefkohl climbed aboard Mugford. The mess attendant followed, still holding his jaw.

Two cruisers’ fates remained in the balance: Astoria and Canberra. On Bagley, Commander Shoup told Astoria’s Captain Greenman, “I think we can save her.” Greenman selected a party of 300 men in Bagley to do so, and all officers volunteered to join the party.

But despite Greenman’s best efforts Astoria’s list was gaining, fires still raged, and shells were still exploding. At about 11 am, a heavy blast was heard below aft of Turret II, and everyone saw sickly yellow gas bubbles emerge on the port side.

The portside patches had given way, and the ship was sinking. For the second time that day, Greenman yelled, “Abandon ship,” and this time for good. Once again Greenman was last to go as the ship turned on her port beam, settled by the stern, and sank at 12:15 pm.

Canberra’s fate had been settled earlier. Turner ordered at 5 am that Canberra had to be ready to join him at 6:30 am for the retreat from Guadalcanal or be destroyed. As Canberra was dead in the water and burning fiercely, Commander Walsh, running the cruiser while his captain lay dying, ordered the ship abandoned.

The destroyer Patterson had been alongside since 3 am, on Bode’s orders, fighting fires and aiding the wounded. At 5:15, Patterson called in Blue to help evacuate the cruiser amid light rain. Canberra, listing 15 degrees, was blazing smartly amidships.

Patterson took aboard 400 men, 100 of them wounded. Just before 7 am, Canberra was clear, and the destroyer Selfridge moved in for the execution. She hurled 263 rounds of 5-inch shells into the burning Canberra, which did not sink. Ellet added 105 more, and Canberra defiantly remained afloat. Selfridge tried her torpedoes, but like most American fish of the time they malfunctioned. Finally, Ellet hit the target, and Canberra sank a little after 8 am. Her crewmembers, lining the decks of the American destroyers, cried at the sight.

One last cripple remained, Ralph Talbot, but nobody knew where she was. With her radio room shot out, dead in the water, and listing 20 degrees, she was in parlous shape. Through judicious patching, Ralph Talbot was able to restore power, and at 12:10 pm Callahan rang his engine room. The destroyer headed off at 15 knots to rejoin the fleet.

Chicago turned up at 9 am, making 15 knots with her damaged bow and spewing oil. Crutchley ordered Bode to pump out the flooded compartments and head home as quickly as possible.

With the survivors aboard, the sound cleared, Fletcher in retreat, the sky empty of American planes, lacking surface ships to protect him by night, and wounded survivors to take home, Turner had to make the tough decision—stay or run.

The problem was that not all the supplies had been unloaded. Turner knew he could not leave that day and ordered his ships to resume unloading, hoping there would be no submarine or air attack.

There was none. Instead, Japanese airmen spotted Jarvis, down at the bow and trailing oil. They put all their energy on her and sank the damaged destroyer. All 246 members of its crew, including Lt. Cmdr. Graham, died.

The battle was not quite over yet. Mikawa and his merry men were heading home, and the victorious admiral detached the four warships of Cruiser Division Six to head for Kavieng to fuel. On Monday, August 10, at 8 am, the cruisers were triumphantly steaming along without destroyer escort northwestward, 100 miles from Kavieng, when the U.S. submarine S-44, under Lt. Cmdr. John R. “Dinty” Moore, spotted them 9,000 yards off, headed straight for him. It was a perfect setup, and when the last ship in the quartet was 700 yards away, Moore fired four torpedoes. The elderly S-class boats used different torpedoes from the ones that gave the rest of the Navy fits, and all four slammed into Kako’s hull. Kako sank in five minutes, taking 34 men to the bottom with her, the first installment of revenge.

Savo had been an immense Allied disaster. Quincy lost 370 dead, Vincennes 332, Astoria 216, Canberra 84, Ralph Talbot 11, Patterson eight, and Chicago two. It all added up to 1,024 American and Australian bluejackets dead and 708 wounded. The loss of Jarvis the next day put an additional 247 dead on the balance sheet.

Just as importantly, the Allies would have to pull their supply ships away from Guadalcanal, leaving the Marines there below the minimum amount of supplies needed to hold the island.

In comparison, the Japanese suffered a mere 35 dead and 51 wounded in the battle, and a further 34 dead and 48 wounded when Kako was sunk.

First to report on the mess was Crutchley. On board Australia, he wrote personal letters to Turner and to the Royal Australian Navy’s leadership asking why Blue and Ralph Talbot had not reported Mikawa’s force, and there had been no enemy report from anyone. “The fact must be faced that we had adequate force placed with the very purpose of repelling surface attack and when that surface attack was made, it destroyed our force … the only thing that can be said is that the convoy was defended but the cost was terrific and I feel that it should have been the enemy who should have paid, whereas he appears to have got off free.”

New Jersey-based author David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He also maintains a website dedicated to the daily events of World War II.

Great articles

Great article, Thx.

We had radar controlled big guns…torpedoes in subs that did not fire…brave Aussie and American sailors and gunners…and no communications.

Sad, and preventable. Who was asleep at the wheel?

The DD USS Blue was on Pickett and had sailed within 500 yards or so of the main Japanese line of Battle. No one has figured out why she did send out a warning or didn’t spot the Imperial Japanese Navy. Has anyone checked out the report from the Blue and said what happened.