By David A. Norris

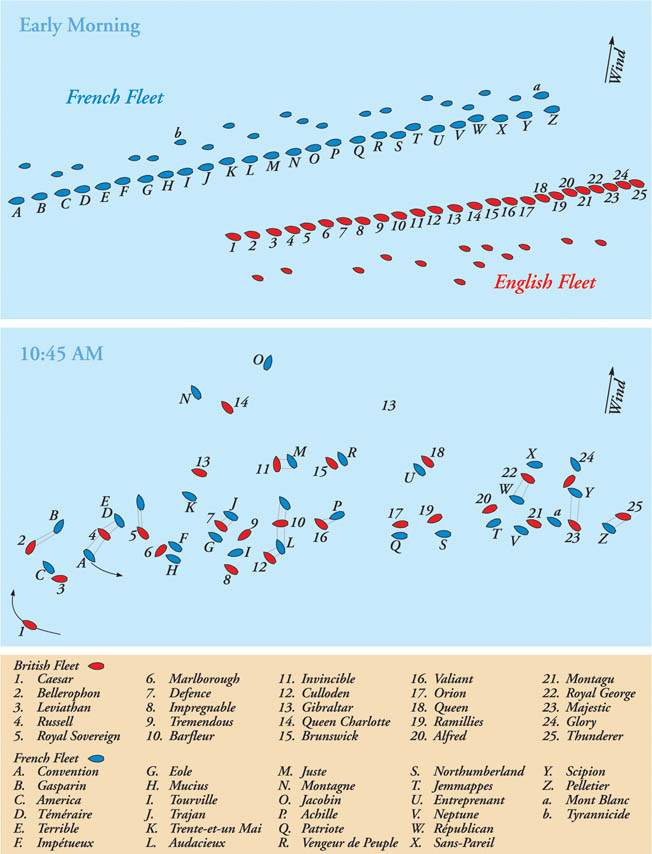

British Admiral Lord Richard Howe, standing on the quarterdeck of his 100-gun ship of the line Queen Charlotte, snapped his signal book shut on the morning of June 1, 1794. “Black Dick” Howe, his sailors said, never smiled except when a battle was near. He was smiling now. For two days, his fleet had clashed inconclusively with the French, and two more days of fog had kept the opposing warships apart. Now his captains had their orders, and the time for giving more signals was past. Howe’s 25 ships of the line sailed toward a formidable battle line of 26 French men of war. The stage was set for the Glorious First of June, the first epic naval action of the Napoleonic Wars.

The Last Hope of Revolutionary France

Beginning in 1789, Great Britain had watched anxiously as the French Revolution careened more and more out of control. By 1793, the ongoing Reign of Terror menaced the rest of Europe, and France was at war with Britain and much of the Continent. By pouring every bit of her national effort into mobilizing a vast army, France held her own and even gained ground against her enemies. But in early 1794, the revolution was in real trouble. Political turmoil and social upheaval, combined with bad weather, had caused a famine serious enough to threaten the new regime.

Food to ease the famine and prop up the revolutionary government was available from only one source—the United States. Still resentful toward Great Britain and grateful to France for help in winning their independence, Americans were happy to sell wheat to the French, whose agents purchased vast amounts of flour and other food, loading it aboard a huge convoy of French and American merchant vessels at Baltimore, Annapolis, and Norfolk. Rear Admiral Pierre Jean Van Stabel left Brest late in 1793 with a few warships to guard the food convoy. One French frigate, Charente, arrived at Norfolk with 22 million livres in coin, and a French consul brought more funds by wagon from Baltimore. As the French and American ships were loaded, more vessels arrived loaded with produce from the French West Indies. French passengers desperate to return to their homeland piled onto the ships. Men who could handle weapons were assigned to the accompanying warships; the rest were scattered on the merchantmen, many of which carried cannons of their own.

The last hope of revolutionary France, 117 ships laden with food, left Hampton Roads on April 15, 1794. In command of the convoy, Van Stabel had only two 74-gun ships, a pair of frigates, and a brig to guard against depredations by the British.

The French Fleet vs the Royal Navy

Keeping the Royal Navy away from the food convoy was the job of Rear Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse. Villaret began his military career on land in the King’s Guards, but transferred to the navy after killing a fellow soldier in a duel. After 1789, the revolutionists arrested or executed most of the senior naval officers. Villaret was one of the fortunate few sea officers who came through the Reign of Terror with their heads still attached. He had convinced the revolutionaries that his loyalty was to France herself, no matter who ran the country.

Some of Villaret’s captains had also been naval officers, but among the rest were merchant ship officers without military experience. Until recently, one captain had been a boatswain; another had risen quickly in rank from common seaman. The crews’ efficiency was impaired because many seasoned mariners had been pulled from the navy and sent into the army, to be replaced by inexperienced landsmen. Revolutionary doctrine held that true zeal and loyalty to France was more important than experience and nautical skills. That very much remained to be seen.

The French admiral had a potentially dangerous guest aboard his flagship, the 118-gun three-decker Montagne. To ensure that Villaret remained politically correct, the revolutionary government had sent a representative named Jean Bon Saint-André to sail with the admiral and report on his conduct. As a member of the revolutionary National Convention, Saint-André had voted for the execution of Louis XVI. He made it clear that Villaret faced the same fate if he failed to protect the grain convoy. The same penalty would apply to any officer who surrendered a ship that was not actually sinking.

The French Navy’s efficiency may have been hurt by the loss of experienced officers and sailors, but the British Navy was not at peak efficiency, either. The war had caught both nations unprepared. After the end of the Revolutionary War with the United States, Britain’s peacetime navy had been slashed to a fraction of its former size. Now, with a new war threatening national survival, naval press gangs ruthlessly scoured the streets of English port towns. Desperate for more sailors, the navy even raided ships of the commercial East India Company, leaving their vessels with barely enough hands to sail them. The Royal Navy was so short of marines that soldiers from several army regiments were reassigned to their ships.

Admiral Howe was the commander of the Royal Navy’s Channel Fleet. Born in 1726, he saw his first action in the West Indies during the War of the Austrian Succession in 1742. He commanded the Royal Navy’s North American forces during the American Revolution, although he had some sympathy for the rebellious colonists. Called “Black Dick” because of his swarthy complexion and taciturn nature, Howe was a strict disciplinarian, but he was always concerned with the welfare of his men and so was popular with them, despite his harsh regimen.

After returning from an uneventful cruise in April, the Channel Fleet sailed from Cowes on May 2, 1794. The British were not yet closely blockading the French ports and the fleet had spent the previous winter in port to save wear and tear on the vessels and crews. When they finally took to the sea, they had orders to escort the East India ships leaving England. After detaching several warships for convoy duty, Howe was left with 26 ships of the line. Rear Admiral George Montagu escorted the Indiamen as far as Cape Finisterre, and stayed to patrol the Bay of Biscay with six 74-gun ships.

Finding the French Fleet

On May 6, French Rear Admiral Joseph-Marie Nielly left Rochefort with six ships of the line to rendezvous with the convoy. Villaret waited at Brest until May 16, when he slipped out under the cover of fog. A day later, the French ships passed so close to Howe’s fleet that they plainly heard drums beating and bells ringing as fog warnings on the British ships. Howe didn’t know that Villaret was loose until a check on the harbor at Brest on May 19 found it empty of warships. It was just as well—Howe wanted to catch the French warships on the open sea, away from the protection of friendly shore batteries.

On the day Howe learned the French were out, Nielly intercepted a convoy from Newfoundland that was guarded by a single frigate, Castor. The French snapped up the frigate and many of the ships. That same day, a convoy of Dutch ships out of Lisbon ran into Villaret, and many of them also fell to the French.

Howe worried that Montagu’s six ships might be overwhelmed next by Villaret. On May 21, Howe recaptured one of the fish-laden Newfoundland ships and learned that Villaret was sailing west into the Atlantic, away from Montagu. Armed with the knowledge that Montagu’s ships were safe, Howe ordered him to sweep the ocean for the French grain ships. Montagu searched fruitlessly for the convoy, then headed back to England, docking at Plymouth and depriving Howe of six much-needed ships of the line.

The British saw no sign of Villaret or the convoy for several days. They took two French corvettes that had followed them, believing them to be part of the greater French fleet. Too short of hands to man them, Howe had to burn the corvettes. At last, on May 28, a frigate sighted a flock of sails in the distance. They had found the French fleet.

Two Days of Combat

The French held the weather gage (that is, they were closer to the direction the wind was blowing, giving them the choice of either fighting or sailing away) and were between Howe and the grain fleet. Villaret turned west to draw the British away from the convoy. Howe followed. The French admiral must have suffered while watching his fleet trying to maneuver. Smoothly trained crews almost slammed their ships into clumsily handled vessels that blundered into their way. Several ships fell so far astern of the rest that Villaret feared the British would take them, so he had his ships tack to let the slow ones catch up. Howe echoed the tacking maneuvers and then ordered a general chase. Late in the afternoon, his leading ships opened fire at long range. Plunging through heavy seas and squalls, rain lashed the ships as water sloshed through their lower gun ports.

The 110-gun Revolutionnaire dropped behind to deal with the nearest British ships. She exchanged fire with several vessels, but the 74-gun Audacious took the brunt of the attack. The guns of Audacious were much better handled than those of the French, which evened the odds between the two. By dark, the masts and rigging of Audacious were splintered and torn, but she had fought the larger adversary to a standstill. British fire toppled Revolutionnaire’s mizzenmast and shot away several spars and much rigging. The larger ship stopped firing, and it looked in the darkness as though she had struck her colors. But the crew of Audacious had her hands full repairing their own damage and could not secure the prize. During the night, another French ship towed Revolutionnaire out of harm’s way. Audacious, too, had to drop out of the fight and limped back to England.

The fighting intensified on May 29. A hazy dawn found both fleets in line of battle, about six miles apart. Howe ordered his fleet to pass through the French line, which would give them the weather gage, and engage the enemy close up. At the urging of his flag captain but against his own better judgment, the admiral ordered the 80-gun Caesar under Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy to lead the attack. Molloy failed to pile on enough sail, and the rest of Howe’s ships backed up behind him. Three ships, including Howe’s flagship Queen Charlotte, steered on their own, and broke through the enemy line. The admiral then signaled for a general melee, and about a dozen British ships closely fought the French from the enemy’s leeward side.

A red-hot French shot crashed into the captain’s cabin of Orion. The shot kept rolling about and burning unfortunate sailors before a fast-thinking first lieutenant caught it in his speaking trumpet and tipped it over the side. An accidental shot from Gibraltar wounded Sir Andrew Douglas, Queen Charlotte’s flag captain. Douglas had the wound dressed and returned to duty, although he was unable to put his hat on over his bandage. When the firing died down in late afternoon, British losses totaled 67 killed and 128 wounded. No ships were captured or sunk, but three badly damaged French ships left the fleet and headed for port.

The Battle Lines Collapse

On May 30 and 31, the fog returned and hid the combatants for two days. Four more ships of the line joined Villaret, bringing his strength back up to 26. The fog began lifting late on May 31. Howe decided to begin battle the next morning rather than start a late-afternoon action that would run on after dark. Captain Thomas Troubridge and 50 of his crew of the captured frigate Castor were prisoners aboard Sans-Pareil during the battle. After the inconclusive fighting of the first two days of the action, and seeing Howe decline battle on May 31, Troubridge had to listen to Captain Jean-Francois Courand insult Howe and the British fleet. Troubridge told him to wait and see.

The morning of June 1 dawned bright and clear, with a moderate breeze. Both fleets were sailing east to west in line of battle, about four miles apart. Howe signaled at 7:16 am to attack the enemy’s center, and he added an additional nine minutes for the ships to pass through the enemy’s line and engage to leeward. On the leeward side of the French, the British would suffer greatly from the clouds of battle smoke, but it would also be harder for the French to escape. Damaged ships would find it especially hard to sail away against the wind.

Howe waited a few minutes for the men to have breakfast. Then, shortly after 8 am, the British headed toward the French in line, 25 ships abreast of each other, sailing diagonally instead of straight ahead. Another signal at 8:38 ordered each ship “to steer for, and independently engage, the ship opposed to her in the enemy’s line.” As a final signal, Howe ordered one prepared for close action. When an officer protested that the codebook had no such signal, Howe replied, “There is a signal for closer action, and I only want that to be made in case of captains not doing their duty.” Howe then snapped his signal book shut.

The French opened fire at long range just before 9:30. The British, sailing at an oblique angle, made good targets but could not fire back easily. The 74-gun Defence piled on sail and outdistanced the rest; other ships made less sail and hung back. Some captains later claimed that they believed the order to break the French line was optional, only to be done if practicable, and stayed back, firing at long range. In 15 minutes, the orderly British line was scattered and uneven. Howe had to start sending signals again, after all. Only seven ships actually broke though the French line, and the battle broke up into a jumbled series of single-ship duels.

A Brave Defence

Captain James Gambier, born in the Bahamas in 1756, commanded Defence. Gambier was so religious and morally strict that he seemed quite eccentric to the loose-living sailors. They called him “Preaching Jemmy.” When Defence opened fire, they were close enough to the enemy that the men heard their shot thudding into French hulls. As enemy fire grew hotter, a sailor named John Polly joked that he was so short that French shot would pass over his head. Moments later, a cannonball tore off the top of his head. Speeding ahead of the fleet, Defence was the first ship to break through the French line, pushing between Mucius and Tourville.

The gunners could barely see each other through the powder smoke on Defence’s gun deck. Midshipman William Dillon remembered that “the guns were so heated that, when fired, they nearly kicked the upper deck beams. The metal became so hot that fearing some accident, we reduced the quantity of powder.” Gambier lost his mizzenmast at 10:30, and the mainmast fell an hour later.

Mucius and Tourville took advantage of the crippled condition of Defence to sail away, but soon a French three-decker loomed toward them out of the smoke. It looked as though the French would rake their stern, and Defence was unable to steer. There was nothing to do but order all hands to lie down and wait for the coming broadside. A lieutenant, on the edge of panic, confronted the captain and exclaimed, “Damn my eyes, Sir, but here is a whole mountain coming toward us.” Gambier was more upset by the officer’s language than he was by the French. “How dare you, Sir, at this awful moment, come to me with an oath in your mouth? Go down, Sir, and encourage your men to stand to their guns.”

The French ship, also battle damaged, was only able to loose a few scattered shots, one of which finished off Defence’s already disabled foremast. Another frightening moment came when Royal Sovereign, which was coming to her aid, mistook Defence for a French ship and fired on her.

After the fighting slowed, Midshipman William Dillon, his uniform and shoes damp with sweat and blood, made his way to the quarterdeck. He stopped to shake hands with the fellow midshipmen he found alive. His conversation with Captain Gambier was cut short when the second lieutenant, who was drunk, ordered the crew to fire several of their guns. Sparks ignited the foretopsail, which was lying over on its side. Once the fire was put out, the frigate Phaeton took the disabled Defence under tow at about 1 pm.

Captain Thomas Pakenham of Invincible, described as a “harum-scarum Irish captain,” was a study in contrast with Gambier. A widely told anecdote had it that Invincible pounded away at a French ship until the enemy’s return fire stopped. Pakenham then hailed the French vessel and asked if it had surrendered. When the French said they had not, he replied, “Then damn you, why don’t you fire?”

As his ship drew near the battered Defence, with her crew clearing the wreckage from their decks, Pakenham hailed Gambier. “You are pretty well mauled,” he said, “but never mind, Jemmy, whom the Lord loveth, he chaseneth!” Gambier asked in return how many men Invincible had lost. “Damn me if I know!” said Pakenham. “They won’t tell me, for fear I should stop their grog.” Pakenham’s crew was already splitting up the rum rations of their dead comrades.

Duels of the Glorious First of June

During the battle, Leviathan’s guns pelted their opponent, the 74-gun L’America, not only with iron but also with silver. When the Toulon dockyard was in royalist hands, Captain Lord Hugh Seymour took a fancy to some brass howitzers and had them hauled on board. The dockyard staff sent along some small red metal cans that they took to be canister shot for the brass guns. Instead of lead, these tins were packed with French silver coins that had been hidden at the dockyard by a French nobleman who for some reason thought they would be safe there. After L’America struck her colors, the side that had faced Leviathan was speckled with silver coins. Victorious British tars plucked out of her woodwork as many of the big silver-dollar-sized pieces as they could find.

In the fighting, Marlborough was dismasted and her captain and second-in-command severely wounded. Lieutenant Monckton, next in command, declared that he would be damned if the ship would surrender, and that he would nail her colors to the stump of the mast. At that moment, a rooster freed from its shattered coop perched on the shattered stump of the mainmast. The rooster flapped its wings and crowed, and the crew broke into a rousing three cheers. Morale restored, the crew was soon aided by a frigate that took the shattered Marlborough under tow. The gallant rooster was later presented to Lord George Lennox, the garrison commander at Portsmouth. The ship’s tars visited the bird often while the ship remained at Portsmouth, and the rooster lived to a ripe old age.

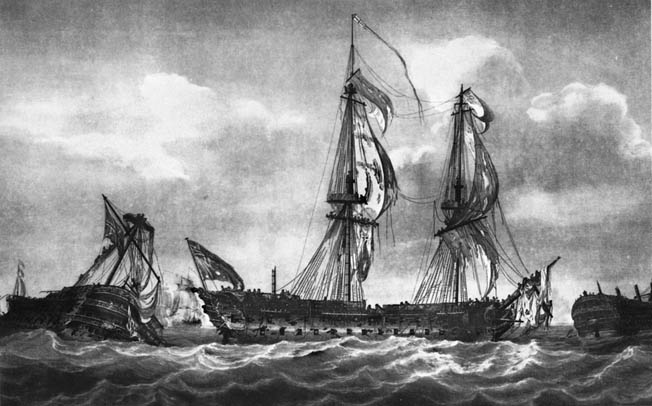

None of Howe’s ships fought harder than the 74-gun Brunswick. She steered to break the French line between two other 74’s, Achille and Vengeur du Peuple. When the latter pushed forward to close the gap, Brunswick’s starboard anchors caught in Vengeur’s forechains. The master of Brunswick asked Captain John Harvey if he should cut them free. Harvey replied, “No. We have got her, and, we will keep her.”

Brunswick’s gunners blasted through eight of their lower deck port-lids because they were jammed shut by Vengeur’s hull. As guns pounded at point-blank range, Vengeur’s short-barreled carronades swept the British decks with loads of langrel, a deadly mixture of old iron bolts, nails, scraps, and junk. French musket fire struck several men and tore three fingers off of Captain Harvey’s right hand. Harvey’s crew always took great pride in Brunswick’s figurehead, a statue of the Duke of Brunswick. When a French shot knocked the hat off the duke, Harvey donated a spare cocked hat to the ship’s carpenter. The carpenter climbed out and nailed the replacement hat onto the figurehead, where it remained for the rest of the battle.

Locked together, Brunswick and Vengeur eventually drifted a mile to the leeward of the battle line in a little over an hour. Achille also engaged Brunswick until the British ship shot away her remaining mast and she drifted away. Harvey pulled himself to his feet after a large splinter knocked him to the deck. At about 11:30 am, his right arm was shattered by a broken piece of bar shot. He refused help to get below to the surgeon. “My legs,” he said, “still remain to bear me down to the cockpit.” His final words while on deck were, “The colors of the Brunswick shall never be struck!”

Vengeur Surrenders

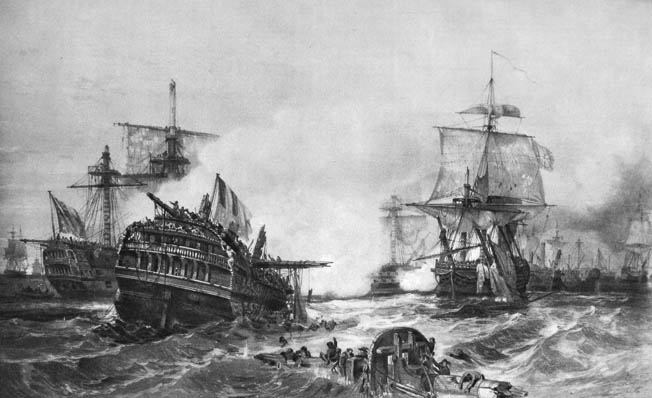

The battle dragged on until Vengeur struck her own colors at about 2:15. The remnants of the French ship’s masts toppled overboard shortly afterward, as did Brunswick’s mizzenmast. The ships at last cut themselves free from each other and drifted apart. Twenty-three of Brunswick’s guns had been dismounted, and the ship had been set on fire three times by French muzzle blasts.

Water poured into Vengeur through shot holes and her lower ports, and she sank at 5:30 that afternoon. None of Brunswick’s boats were usable, but other British ships saved some of the French sailors. The crippled Brunswick drifted so far with the wind that the remnants of the French fleet blocked her way back to Howe’s ships. Brunswick then set up a jury rig and made her way to England.

Because the ships were often so close to one another when firing, scorched fragments of French powder bags or cartridges littered the British decks. Many of these cartridges were made of parchment and bore medieval ink and painted lettering. The cartridges had been made from centuries-old manuscripts of church music and aristocratic pedigrees seized by the anti-clerical revolutionaries. By the time Vengeur struck her colors, the battle was winding down. Six French ships of the line besides Vengeur were captured. Among them was one ship with the decidedly non-French name of Northumberland; she was a French-built 74-gun vessel named for a British ship captured back in 1744.

Holding Off the Pursuit

Captain Troubridge had his revenge for enduring Captain Courand’s insults the day before. When Sans-Pareil surrendered to Majestic, Troubridge and his men from Castor were already in place as a prize crew. Villaret rallied his remaining ships and withdrew; he managed to rescue some dismasted vessels from capture. One of his ships, Scipion, lost all three masts and had 17 guns dismounted. Red-hot cannonballs spilled from smashed furnaces and rolled around the deck, setting small fires. A total of 64 of Scipion’s crew was dead, and another 151 were wounded. Even so, Scipion’s crew got up enough sail to make it back to France. By about 6:15, Villaret and his 19 remaining ships had disappeared over the horizon.

Howe let them go. In later years, he was much criticized for settling for an incomplete victory. But Howe had spent five straight days on deck, catching only occasional catnaps in a chair. The long days filled with fighting and emergency repairs had exhausted his officers and men as well. The admiral collapsed from physical strain and was carried away to rest. His captain of the fleet, Sir Roger Curtis, took command. It was growing dark, and while no British ships were lost, Curtis felt that too many of them were damaged to risk an aggressive pursuit.

Naming the Battle

Of about 17,000 men in Howe’s fleet, almost 300 were dead and 850 wounded. French casualties were much higher, perhaps as many as 7,000. The intense firing and thick smoke led many sailors to think that several ships in addition to Vengeur had been sunk. Some accounts of the battle include the French ship of the line Jacobin among the losses. A vivid legend grew about the steadfast resistance of Jacobin, which was said to have sunk with her upper deck guns blazing while water flooded though the lower gun ports. Actually, although heavily damaged, Jacobin managed to make it back to France.

Newspapers reported that 4,000 French prisoners had been taken to Hilsea Barracks at Portsmouth, with another 700 landed at Plymouth. Among the Portsmouth prisoners were Captain Jean Francois Renaudin of Vengeur and his 12-year-old son. Boats from different ships had rescued Renaudin and his son, and neither knew the other was alive until they were reunited on English soil.

A few early prints and other sources referred to Howe’s 1794 action as the Battle of Ushant. The name didn’t stick because the battle was fought 400 miles away from that point, and the British began calling it the Battle of the First of June. The French had the same idea, calling it the Bataille du Treze Prairial de l’An Deux, using the date as rendered in their new revolutionary calendar.

The lasting name for the battle came from the pen of English playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, who wrote a London theatrical production to commemorate the victory. Sheridan caught the mood of the nation with his popular theatrical extravaganza. Presented at the Royal Theater in Drury Lane on July 2, the production combined a love story between a young woman and one of Howe’s sailors with comedy, song, dance, and a scene where the great sea battle was conducted on stage with two pasteboard fleets. Sheridan and his co-writers wrote, cast, rehearsed, and mounted the production in three days’ time. They were in such a rush that the performance was well under way before the last line of dialogue was written. The performance netted 1,300 pounds for the benefit of those left widowed or orphaned by the battle.

Sheridan’s title for the theatrical benefit, The Glorious First of June, stuck as the name of the battle. No wonder. As soon as news of the battle reached London, the city was delirious with joy. Previous army and navy failures were forgotten. Countless thousands of homes kept their lights on all night to celebrate the victory—and to avoid attracting the attention of patriotic mobs that broke any windows not illuminated.

A Strategic Victory for France

The French ships, with hundreds of brass guns manufactured in Sweden, brought a great deal of prize money. Some 1,400 guineas went to each captain, compared with the two guineas given to the ordinary sailors and marines. Howe, who was made an earl, turned over his share to the wounded and the families of the dead.

The British were happy with their tactical victory in the sea battle between the two great fleets, but the Glorious First of June was really a strategic victory for France. On June 12, the grain convoy from America anchored in France. Only one of the ships had been lost, an unlucky vessel that foundered in bad weather. The French leadership considered the loss of seven warships a cheap enough price to pay for netting enough grain to stave off hunger and unrest and retain their hold on the country.

Twenty-one years mostly filled with war followed. In 1815, Bellerophon, a 74-gun ship that had fought in the Glorious First of June, carried the defeated Emperor Napoleon from France to England on the first stage of his journey to exile at St. Helena. In 1848, long after the Glorious First of June, Great Britain awarded medals to her naval veterans. The lowest-ranking of the recipients of the Naval General Service Medal who had been present at the Glorious First of June was one Daniel Tremendous McKenzie. McKenzie was born to the wife of a sailor aboard HMS Tremendous on June 1, 1794. On his citation, his rank during the battle was officially listed as “baby.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments