By William F. Floyd Jr.

On the evening of October 13, 1939, The German submarine U-47 surfaced off the Orkney Islands in the North Sea. Lt. Cmdr. Gunther Prien, a promising U-boat commander, pulled himself up on the bridge. He soon discovered that, although weather conditions were near perfect, the Aurora Borealis had made its appearance, illuminating half of the horizon and threatening to make the boat’s presence known. This was the first command for the 31-year-old Prien, who had been chosen by Rear Admiral Karl Dönitz, head of the German submarine force. Prien was to carry out the first special U-boat operation of the war, an attack on the British fleet at its home base of Scapa Flow.

On October 8, U-47 had left her mooring in northern Germany bound for the North Sea. After Prien revealed the mission to the crew, the U-47 slipped into Holm Sound, one of the entrances to Scapa Flow. By 12:30 am, October 14, the boat was inside Scapa Flow. At first Prien was able to make out the shapes of several destroyers, but then he spotted the battleship HMS Royal Oak and the seaplane carrier HMS Pegasus. U-47 was now about 4,000 yards from her intended target and was in position to attack.

The bow torpedo tubes were aimed, and the order to fire was given. Three minutes later, one of the torpedoes exploded harmlessly against either the bow or anchor chain of the Royal Oak. Puzzled, Prien turned his craft around and discharged a stern torpedo, which also missed its mark. Those aboard the Royal Oak thought the torpedo explosion was caused by an internal source, thus giving Prien a second chance. U-47 was again put into position to attack, and the torpedoes were fired. This time the Royal Oak was struck by a torpedo, and the harbor came to life. The Royal Oak soon sank taking 833 of her 1,234 officers and men down with her.

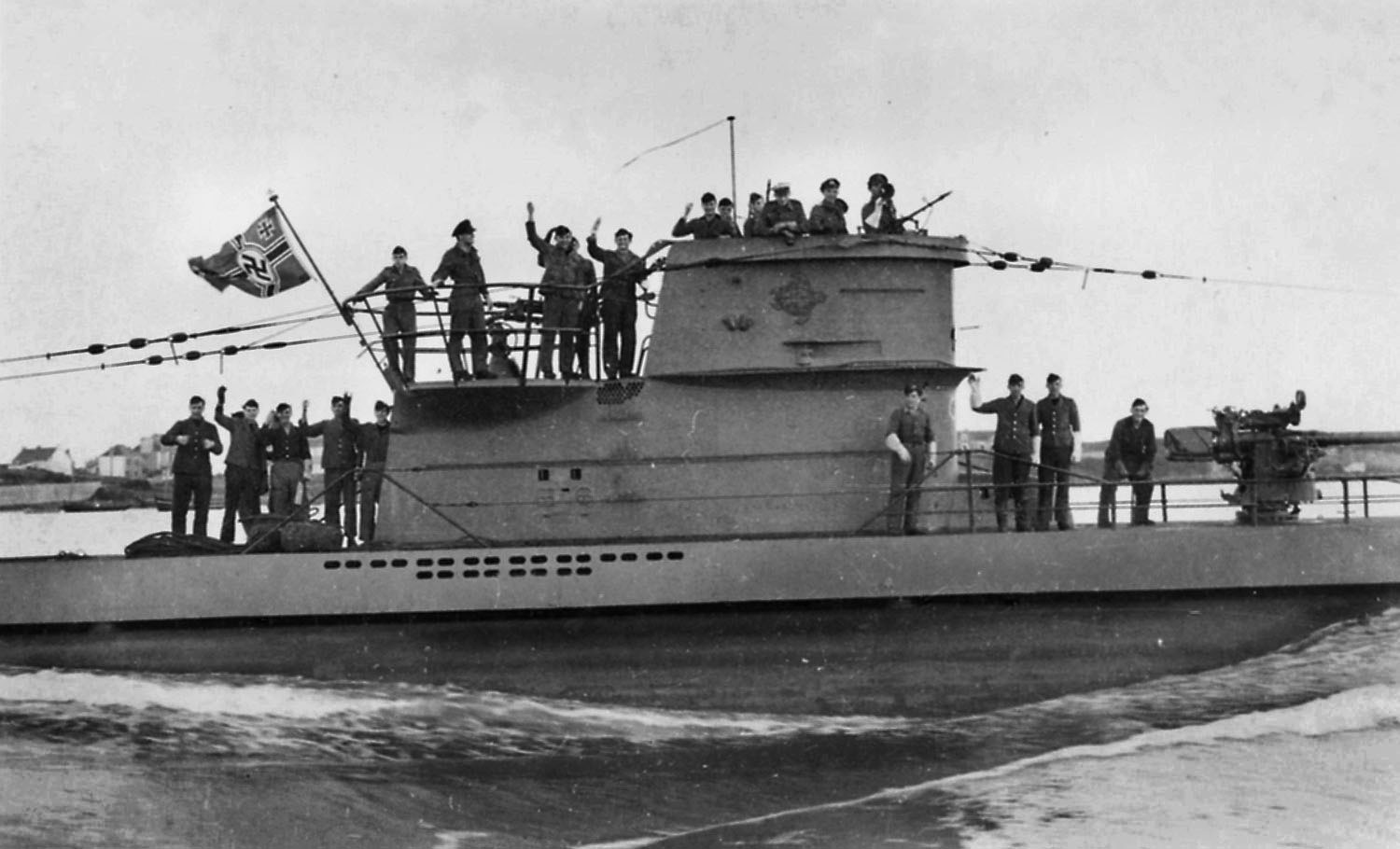

The submariners were exultant, but their worst ordeal still lay ahead, which was to escape unscathed. The tide was running against them, and even at full power U-47 moved along at only slightly more than one knot. A searching destroyer was drawing near, her searchlight probing the darkness but failing to locate U-47 as it made its way into Holm Sound. Soon U-47 slipped back into the North Sea. “The glow from Scapa Flow is still visible,” wrote Prien in his log. Two weeks later, Gunther Prien and his crew were the guests of Adolf Hitler in Berlin. At the Chancellery, Prien was decorated with the Knights Cross.

According to the terms of the Versailles Treaty, Germany was barred from having submarines. However, when Germany decided it could no longer abide by the treaty, one of the first steps it took was to rebuild its vaunted submarine force. In 1934, the greatest submarine fleet the world had ever known was reestablished.

The Kriegsmarine (German Navy) had continued U-boat research and development through the Krupp front in Holland. The operation produced three submarine prototypes: one small (250 tons), one medium (500 tons), and one large (750 tons). The 250-ton and 500-ton boats were built in Finland. One 750-ton boat was built in Spain along with a plant for manufacturing torpedoes and tubes. The speed with which these types were built following Germany’s pronouncement that it considered itself no longer bound by the Treaty of Versailles was an indication of German technical skill and knowledge in this particular field.

An important factor related to the manufacture of submarines during this period was their limited range when submerged. They spent the majority of their time on the surface and normally only submerged during daylight hours to escape detection or when approaching a target for an attack.

Before the outbreak of hostilities in 1939, Germany had 65 submarines of eight different models on hand. After the outbreak of war, construction was greatly increased. Supply was one pressing need for the submarine fleet. For some models, military requirements were sacrificed to increase cargo capacity to allow U-boats to stay at sea for longer periods. The Germans continued until the end of the war to make improvements and modifications, but in the end the overpowering force of the Allies was too much to overcome.

Of the various classes of U-boats, the type VII was the most ubiquitous with more than 700 produced. The 220-foot-long, 31-foot-high vessel could carry 14 torpedoes fired from four tubes located in the bow and an additional tube located in the stern. The Type VII was armed with the 88mm SK C/35 naval gun on the deck mounted in front of the conning tower. The diesel-powered vessel had a range of 8,500 nautical miles.

No other vessel of war had poorer living conditions than a U-boat. A U-boat crew included about 50 men. Patrols could last anywhere from three weeks to six months. During this time the men were unable to bathe, shave, or change clothes. The availability of fresh water was limited and strictly rationed for drinking. The hardship was even more unbearable when one of their water tanks was filled with diesel fuel to extend the vessel’s time at sea. Those on board were allowed only the clothes on their backs and one change of underwear and socks along with one small locker for personal items.

With such a shortage of space, sleeping arrangements were also extremely limited. The crew would often resort to hot bunking. In this arrangement, as soon as one person had crawled out, the next person would crawl in. Another major challenge on board was food. Before leaving on patrol, as much food as possible was crammed into every available location. Even a toilet was used to store food, making only the second toilet available for use by the crew until the food in the first toilet was used up.

The long periods at sea could take a psychological toll on crew members. Danger was always present for the crew. Long periods of boredom could be replaced with moments of sheer terror when under attack by depth charges or on the surface in rough seas.

But the U-boats had a fearsome reputation. “The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril,” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said after the war. The U-boat war in the Atlantic was the longest continuing fight of World War II. It picked up pace following the fall of France on June 25, 1940, and lasted until the last day of hostilities in Europe.

After France was subjugated, the German U-boats were able to operate from bases on France’s Atlantic coast. The importance of the naval battle in the Atlantic could not be overstated. If Britain’s lifeline of Allied supplies was cut off, it would have to sue for peace with Germany. With Britain out of the war, the chances of the Allies launching an amphibious invasion of the European continent would be practically nonexistent. From the outset of the war, Dönitz (who became grand admiral in 1943) recognized this weakness, and he took steps to fully exploit it.

On September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany, the U-boat force had only 57 boats in commission with 20 ready for combat. The German Navy also had a fleet of surface ships that took part in attacks on Allied shipping. The effectiveness of the German surface fleet quickly declined when engaged by the Royal Navy. After the war began, Hitler approved an accelerated U-boat-building program. However, building a single U-boat could take 12 to 21 months.

Despite this slow growth, U-boats had amazing success against British and neutral merchant ships early in the war. U.S. involvement in the Battle of the Atlantic came about slowly. Long before Germany’s declaration of war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been supporting the British. In September 1940, the United States sent 50 World War I-era destroyers to the British and Canadian navies. By February Roosevelt had started to upgrade the Atlantic Squadron under Admiral Ernest J. King.

On September 4, the first combat incident between an American warship and a German U-boat took place. The confrontation was between the USS Greer and U-652. The Greer dropped depth charges, and U-652 fired torpedoes, but neither ship was damaged and they soon disengaged. On October 31, 1941, while escorting convoy HX-156, the American destroyer USS Reuben James was the first to be sunk by a German U-boat, with the loss of 115 crewmen. The first attack in American waters occurred on January 14, 1942, when the U-123 sank the Panamanian flagged tanker Norness 60 miles off Long Island, New York.

The German U-boat fleet developed different methods of attacking Allied shipping. Dönitz, who was a U-boat captain in World War I, is credited with developing the tactic known as Rudeltaktik, or wolf pack, which was instituted in 1939. In wolf pack doctrine, when a single U-boat located a convoy its crew would radio headquarters. The headquarters staff would broadcast a homing signal that directed other boats to the location of the target. This might result in as many as 15 to 20 submarines attacking a convoy. The wolf pack existed only as a means to attack and would never travel as such. One disadvantage of the wolf pack was that in some cases several torpedoes would be used to sink an Allied vessel when one torpedo could have accomplished the objective.

The U-boat commanders also would use their deck guns as a means of attack. The relatively small size of the U-boat meant that a limited number of torpedoes could be carried on board. It was a general practice that these were kept for valuable targets such as tankers. At other times the 88mm deck gun was used for smaller targets found travelling alone, where a surfaced U-boat was unlikely to be intercepted by Allied warships or aircraft. Another benefit of surface gun attacks was that a merchant captain might surrender after being fired on. The deck gun tactic was particularly successful in attacking Allied convoys and warships accompanying the supply convoys in the early part of the war. In September 1939, approximately 25 percent of ships sunk by U-boats were destroyed by gunfire rather than torpedoes.

The Allies, particularly the British, came up with a number of innovations to counter the U-boat menace and eventually win the Battle of the Atlantic. A number of these methods were fairly simplistic. One such idea was painting the planes of Coastal Command white rather than black, making them more difficult to see from the ocean’s surface. It was also discovered that resetting depth charges to go off at 25 feet rather than at 100 feet resulted in more U-boats being sunk.

At the start of the war, a device called Asdic was one of the many technological devices used against the U-boat. Asdic worked by sending out sound pulses that would bounce back when they hit something, similar to an underwater version of radar. The trouble with Asdic was that its range was limited, and it often was unreliable. By 1941, the Allies were transitioning to a high-frequency, direction-finding system that intercepted enciphered U-boat radio transmissions. The messages could not be read, but that did not matter because the goal was simply to locate the origin of the signal. If two or more stations picked up the signals, the position of the U-boat could be fixed.

Of all the innovations developed to combat the U-boat threat, the breaking of the German Enigma code was the most important. During the 1930s, the German military developed a top secret form of communications using what would come to be known as Enigma. It was an electro-mechanical typing machine able to encode every letter of the alphabet using a series of rotor blades. The scrambled message was then sent as a conventional radio signal. The rotor blades would be reset every 24 hours to further confuse those trying to decipher the messages. To attempt to break the German Enigma, the British government established the Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, a country estate north of London. The staff at Bletchley Park eventually numbered 7,000 with even more workers at stations around the country. The information obtained from breaking the German codes was vital as it would allow Allied shipping to avoid U-boat patrols.

An extremely important breakthrough in solving the German code occurred on May 9, 1941, when an intact Enigma machine was captured. The British already possessed an Enigma machine obtained from Polish intelligence before the war, but the Allies also needed the internal rotors of the machines that were being used. The capture of the Enigma machine occurred when the destroyer HMS Bulldog forced U-110 to the surface with depth charges. The German crew was removed, and a boarding party was sent over. As the boarding party went below, it was obvious the U-boat had been abandoned in haste, as books, charts, and other material were scattered about the boat. The real prize was the coding machine, which was found plugged in as if in actual use when it was abandoned.

The capture of the U-110 was kept a secret because of its sinking. The crew of the Bulldog sent the recovered material to Bletchley Park where it aided in breaking the German naval code.

The U-boat fleet suffered a greater percentage of casualties than any other branch of service on either side during World War II. Of the 1,149 U-boats that entered service, 711 were lost in combat, to accidents, or to the bombing of shipyards, a destruction rate of 61 percent. Of the 39,000 who served in the U-boat force during the war, 27,490 lost their lives in combat or from accidents, a 70 percent fatality rate. For those who survived, 5,000 ended the war in Allied POW camps. Just 6,510 would end the war alive and as free men.

The Germans lost 243 and 249 U-boats in 1943 and 1944, respectively. While U-boat kills were significant, there were other major factors that enabled the Allies to eventually prevail in the Battle of the Atlantic. The most obvious factor is that later in the war there were more U-boats in service, which provided more targets, and the Allies had more weapons to sink U-boats. Another major factor that cannot be discounted was the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. This compelled the U-boat force to abandon its French bases in use since 1940. The result was that U-boats then had to spend more time travelling to and from their home bases and had less time to hunt convoys.

When the U.S. Navy began playing a much larger role in protecting convoys, it was a huge boost to the number of ships getting through. Aircraft carrier escorts provided a much needed increase in convoy security. The United States also transferred a group of extended-range Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers to Newfoundland in 1941. This movement sent a signal to the Germans that the Allies had closed the previously undefended Greenland gap in the Atlantic Ocean.

In the end, the defeat of the U-boats really came down to a numbers game. The strategic goal of the German U-boat force was to sink more shipping than the Allies could replace and force surrender through starvation. This was a fight the Germans were sure to lose. In 1943, the U-boats destroyed 6.14 million gross registered tons of Allied shipping. Over the same period, American shipbuilders alone delivered 18 million tons of new merchant ships for the war effort, four million more tons than the Germans sank during the entire war. The gap in tonnage gained versus tonnage lost would continue in 1944 and 1945.

Although the U-boats were failing to sink as many Allied merchantmen to sustain the tonnage war, the U-boat crews were perishing in droves. Basically, the German goal of isolating Great Britain from the rest of the world, particularly the United States, was bound to fail. Even though the United States was not actually in the war when Germany started sinking merchant shipping, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had no intention of letting Nazi Germany defeat Great Britain. It would have been a disaster of major proportions in that the Allies would have been denied a staging area close to France for the invasion of Fortress Europe and would have, without question, lengthened the war and cost many more lives.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments