By Mason B. Webb

While British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group was marching across Belgium, Holland, and into northern Germany on his way to the Rhine, Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group, made up of Courtney Hodges’s First and George Patton’s Third U.S. Armies, was doing the same on Monty’s southern shoulder.

In the previous weeks, Bradley’s group had overcome numerous rivers in the western half of Germany: the Erft, the Ruhr, the Roer, the Mosel, the Main, the Ahr, the Our, the Lauter, the Saar, the Nahe, the Kyll, and many more—each waterway being more or less vigorously defended by desperate German troops on home soil. Before them now was the Rhine, mightiest of them all.

American intelligence had identified the remnants of 21 German divisions lined up across the Rhine, but all were believed to be exhausted, seriously understrength, and incapable of putting up a sustained fight.

Hitler’s hopes for a victorious last stand were dashed when, on March 7, 1945, elements of the 9th U.S. Armored Division captured the still-standing Ludendorff railroad bridge over the 980-foot-wide Rhine at the town of Remagen, between Cologne and Koblenz.

The unexpected crossing stole the thunder from Montgomery’s carefully planned Operation Varsity, a combined aerial and amphibious assault across the Rhine that he had scheduled for March 24. Now Patton wanted his Third Army to do the same thing.

Third Army’s Crossing

In early March, Patton arrived at the Rhine in the vicinity of Koblenz, south of Remagen, and noted that German resistance in the area had markedly diminished.

He selected Maor General S. Leroy Irwin’s 5th Infantry “Red Diamond” Division to spearhead his army’s effort. Acting as the tip of Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy’s XII Corps, weeks earlier the 5th had moved across the Sauer, Kyll, and Moselle/Mosel Rivers, and crashed through the Siegfried Line, heading eastward.

Patton wasn’t only concerned with beating the Germans; he also very much wanted to beat Montgomery in the race across the Rhine—it was a matter of personal as well as national pride. Using Monty’s perceived dismissive attitude toward American soldiers as motivation, Patton was out to prove, once and for all, that the Yanks were every bit as good as the Tommies. To ensure his success, Patton ordered every combat engineer company with boats and bridging material to get to the river’s west bank as quickly as possible.

Eddy was planning to cross the Rhine on March 23, but Patton pushed him to move up the operation by 24 hours. “We’ve got to get a bridgehead at once,” he said. “Every day we save means the savings of hundreds of American lives! We can take the Rhine on the run!”

Consequently, horrendous traffic jams full of vehicles loaded with bridging equipment clogged every road to the west of the Rhine. The Navy and Coast Guard arrived, too, with a fleet of LCMs and LCVPs. There were also amphibious trucks known as DUKWs.

The U.S. Navy and Coast Guard were not used solely for attacking hostile ocean shores; they also played a vital role in the Rhine crossing operations.One of the types of boats was the Landing Craft, Mechanized, or “LCM,” popularly known as a “Mike” Boat. It was an all-metal vessel that displaced 30 tons and was developed to carry a single Sherman tank.

The LCM’s little brother was the LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel) which could carry 36 men and a crew of three, had a 36-foot length and 10-foot beam that allowed it to carry a two-and-half-ton truck or two quarter-ton jeeps. Both the LCM and LCVP participated in the Rhine River crossings and were piloted by U.S. Navy sailors and Coast Guardsmen, many of whom had served on such boats during the June 1944 Normandy invasion.

The crews were members of the Navy’s Task Unit 122.5, which was composed of five subordinate task units; initially they were equipped with the LCVP, but when it was realized that craft capable of carrying armored fighting vehicles would be required, LCMs were added to the task units.

In early autumn 1944, after the failure of Operation Market Garden, there was little prospect of an immediate drive to cross the Rhine. This gave the Navy the opportunity to join with Army engineers in training for deliberate river crossings using both Army and Navy assets. By November, Army and Navy planners had reached a general outline for crossing the Rhine.

Certain Army engineer units positioned in the rear areas took up the task of training and experimenting with not only their own equipment but with the employment of Navy boats.

The XII Corps’ Crossings

First to set Patton’s gamble in motion was Eddy’s XII Corps, consisting of the 5th and 76th Infantry and 4th Armored Divisions. To fool the Germans into thinking that the crossing would take place at Mainz, XII Corps laid on a heavy smoke screen around the city while the actual crossing occurred at Oppenheim, 10 miles to the south, late on March 22.

Michael Bilder, a sergeant in the 5th Infantry Division, remembered that Patton was hell bent on beating his British rival across the Rhine. “These two had been archrivals since the Allied campaign in North Africa,” he wrote in A Foot Soldier for Patton.

“We may not have cared for Patton, but we liked Montgomery even less. Patton could at least justify his prima donna attitude with results, but Montgomery was far too cautious and seemed to plod along … Monty would not attack until he had overwhelming superiority, and even then he advanced in inches. Most of us felt … he should have been fired.

“Patton told General Eddy to get one of the outfits in XII Corps over the Rhine before Monty. The 5th Division was the only outfit even close to the Rhine, so we got the order to cross it for the Third Army and the United States…. We had to race at full speed for a full day to meet Patton’s deadline.”

According to historian Charles MacDonald in The Mighty Endeavor, the crossing began the night of March 22 as “assault boats rushed forward in a wild ride from stocks carefully maintained far behind the lines since the preceding fall. They did it silently, without advance artillery preparation at the little town of Oppenheim, 10 miles upstream [south] from the Rhine city of Mainz, where the Main River flows into the Rhine.”

The endeavor began with some confusion about how exactly to deploy the boats for troop transport, but once that was figured out, activity quickly accelerated.

In 48 hours the LCVPs carried more than 15,000 troops across the river. With a turn-around time of six to eight minutes, in addition to ferrying troops across the river, the boats brought back casualties and German prisoners of war. All this work was done under sporadic German artillery and small-arms fire as well as occasional air attack, but the Navy suffered no casualties.

Bilder said that his regiment, the 11th, began crossing at 10 p.m. with two battalions of Americans nervously paddling across the rushing water under a bright, full moon, not knowing if the Germans were lying in wait, ready to blast them out of the water.

Another 5th Division soldier in another boat remembered, “It seemed ages before that far shore came into view … my boat nosed into the bank and we stepped out into the water, which was very cold.”

When those first boats touched the opposite bank, several surprised Germans quickly surrendered, but another nearby group fought back briefly, killing 20 Americans before being overwhelmed.

“The area was very lightly defended,” Bilder noted. “Patton had won his race with Montgomery by a full 24 hours.”

Patton called Bradley near midnight on the 22nd to crow about his—or, rather, his men’s—accomplishment: “Brad, for God’s sake, tell the world we’re across…. We knocked down 33 Krauts [aircraft] today when they came after our pontoon bridges. I want the world to know that Third Army made it before Monty starts across.”

In his memoir, A Soldier’s Story, Bradley wrote, “In this first assault crossing of that river bastion by a modern army, the division [5th Infantry] suffered a total of 34 dead and wounded.

Patton wrote in his self-congratulatory tone, “In connection with this crossing, a somewhat amusing incident is alleged to have happened. [Montgomery’s] 21st Army Group was supposed to cross the Rhine on March 24, and, in order to be ready for this earth-shaking event, Mr. Churchill wrote a speech congratulating Montgomery on the first assault crossing over the Rhine in modern history. This speech was recorded and, through some error on the part of the British Broadcasting Company, was broadcast—in spite of the fact that the Third Army had been across for some 36 hours.”

By dawn on the 23rd, six battalions from the 5th Division were on the east side, with more on the way, followed by the tanks of Hugh Gaffey’s 4th Armored Division over newly constructed bridges.

On the 23rd, while Montgomery was up north deliberately moving his pieces like a chess master, and U.S. combat engineers continued to bolt together bridges to bring more men and vehicles to the east bank at Oppenheim, Patton pushed his divisions across as fast as they could go.

As the troops crossed and moved beyond the east bank, there were sporadic firefights, but nothing like the concentrated resistance everyone had expected. In some areas, about the only opposition were some desultory artillery fire and pitiful groups of old men and young boys—the Volkssturm—that had been pressed into service to hold back the American tide. It was an unequal fight; the defenders stood no chance—they either surrendered or were killed.

“Immediately after we crossed the Rhine, the Germans regained their fighting spirit,” Bilder wrote. “German [Luftwaffe] fighters and bombers hit the engineers working to set up a bridge, and their infantry attacked our bridgehead with tank support. Despite this, we advanced and expanded the bridgehead some eight miles wide and five miles deep.

“Heavy fighting continued until March 24. Once we crossed the river, our command advanced us any way they could. We rode any type of vehicle available, and if none were available, we marched on foot. The idea was to keep moving. We had to keep the Germans off balance and prevent them from setting up a stable defense or counter attacking.”

So impressed was Patton with the 5th Division that in a letter dated November 17, 1945—just a month before his death in a traffic accident—he wrote to General Irwin, “Nothing I can say can add to the glory which you have achieved. Throughout the whole advance across France you spearheaded the attack of your Corps. You crossed so many rivers that I am persuaded many of you have web feet, and I know that all of you have dauntless spirit. To my mind, history does not record incidents of greater valor than your crossing of the Sauer and Rhine.”

Patton at Boppard

In his memoir, Patton wrote, “We then flew to the headquarters of the VIII Corps [on March 23] to see about the crossing at Boppard … and the crossing of the 76th Division at St. Goar on the next night.

A 90th Division historian wrote, “The 90th Division crossed the Rhine River over an engineer pontoon bridge on the crossing secured by the Fifth Division; together they secured a bridgehead for the 4th Armored Division.”

Patton was also satisfied with XII Corps’ progress thus far. “All of the 5th Infantry” he wrote, “and the 90th and most of the 4th Armored were across, and arrangements were made for the 6th Armored to start crossing on the morning of the 25th.

“In the meantime, the XX Corps was assembling in the vicinity of Mainz, where we had decided to construct a railroad bridge, because the railway net was such that this was of necessity on our main supply line.”

Patton noted that ensuing operations involved moving one regiment of the 76th Division along the Rhine to capture the high ground overlooking Mainz, followed by the 5th Division crossing the Main River there, and sending the 80th Division to the confluence of the Rhine and Main.

The rest of Eddy’s XII Corps would cross the Main east of Frankfurt, where it was to meet up with Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps. “I told each Corps commander that I expected him to get there first,” Patton said, “so as to produce a proper feeling of rivalry.”

The Luftwaffe, or what was left of it, did not sit idly by. At least 200 sorties attacked the various crossing sites, but American anti-aircraft guns and the XIX Tactical Air Command fought off the enemy, who did little damage.

Patton wrote in his memoir, “On March 24, [Patton’s aide, Colonel Charles] Codman, [another aide, Lieutenant Al] Stiller, General Eddy [XII Corps commander], and I crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim, stopping to spit in the river.”

Codman has a slightly different version: “We proceeded to Oppenheim, through the town, down to the barge harbor, from which the Oppenheimer vineyards are plainly visible. The General’s manner was casual as he led the little procession across the low-lying bridge. Halfway across he stopped.

“‘Time for a short halt,’ he said. Walking on the bridge’s edge, he surveyed the slow-moving surface of the great river.” Then, without further comment, he unbuttoned the fly of his trousers and relieved himself into the mighty Rhine. “‘I have been looking forward to this for a long time,’ he said, buttoning his trousers.”

Photographs taken of the incident prove that Codman’s version was the correct one.

Other divisions were about to be thrust into the river-crossing business. The boats, DUKWs, and landing craft that were still serviceable from the Oppenheim operation were removed from the river and trucked 60 miles north to where Middleton’s VIII Corps units could use them at Boppard and St. Goar.

Major General Frank L. Cullin, Jr.’s 87th “Golden Acorn” Infantry Division crossed at Boppard in the wee hours of March 25. Peter Allen, author of One More River, wrote that while “the 87th Infantry Division crossed in assault boats, the enemy opened a devastating fire. Shells tore apart boats and ripped men to pieces as they battled across the swirling, bouncing current. Conditions were so bad that one regiment had to abandon it and try further south at a different site.”

Richard Manchester, a member of Company K, 345th Infantry Regiment, 87th Division, recalled, “After several days of what passed for R&R in Koblenz, we loaded up and climbed on trucks in the late afternoon of March 24 and moved upstream on the west side of the Rhine to the small town of Boppard. We began to cautiously filter down through the moonlit streets toward the shingled beach.

“The enemy had mounted 20mm guns on the heights across the river. We stayed in the dark shadows. Any movement into the brightly lit streets brought immediate fire from the 20mm guns.

“Around midnight, we climbed into small metal boats. With no explanation, engineers handed paddles to men with no training in how to use them. We set out to cross the river in bright moonlight. I was resigned. Nothing could be done. We were on the river without cover or concealment.”

Somehow, Manchester made it to the other side without incident and there saw “one dead G.I. lying on his side, his face covered with a film of dust. I didn’t recognize him. I looked away. Dead Germans didn’t bother me; I never wanted to look at our own men.”

At 2 a.m. the following morning, Major General Thomas D. Finley’s 89th “Rolling W” Infantry Division, which had only been on the continent since January 21, received orders to move out from St. Goar. By now, of course, the Germans all along the east bank knew that a general assault was underway and that they were probably the next to be attacked.

Two regiments from the 89th hit the water, with the 1st Battalion of the 354th heading for Wellmich and the 2nd Battalion aiming for St. Goarshausen.

James Hahs, also with the 89th, remembered seeing long convoys passing his duty station near St. Goar: “Whatever my work assignment was, it kept me busy most of the day and I paid no attention to the passing convoys. Evening approached and chow was served. When I went to my bedding spot I looked up and noticed that a long convoy seemed to be making a rest stop. I was surprised to see guys wearing sailor hats sitting all over the cargo of landing boats on semi trailers.

“I walked within hailing distance and shouted a joking remark: ‘Hey, you swab jockeys! Are you lost?’ Their reply was something in the order of, ‘We are not lost. We heard that you dogfaces needed a little help, so here we are.’ They were not subject to conversation and did not discuss their reason for being there.

“That night I slept soundly and never heard the convoy start up and move on, for they were gone when I awoke at dawn…. We went up or down stream and crossed on another bridge and returned to St. Goarshausen and set up quarters overnight for the next day. I looked in vain along the banks for any sign of those boats, or the sailors, with no sign of their presence of being.”

An historian wrote that the 89th failed to use smoke to mask the division’s crossing, which left the boatmen exposed and subjected to deadly fire. “In another move that prematurely telegraphed the Americans’ intention to cross the Rhine Gorge to the Germans, the 89th conducted an artillery barrage the evening prior to the assault. Therefore, it is not surprising that, as the first wave began to cross [from Oberwesel to] St. Goarshausen and Wellmich, the Germans were prepared for their attack.

“The defenders initiated with heavy small-arms fire, machine guns, and 20mm anti-aircraft guns; they even illuminated the entire engagement area by shooting a barge soaked in gasoline, providing clear fields of fire on the American soldiers trying desperately to paddle their way across the stiff current.” Casualties were alarmingly high.

Ed Quick, an artilleryman with the 89th, recalled that his B Battery convoy “moved slowly along the twisting road leading to the riverside town of Oberwesel. As we reached the crest of the hill and looked down into the Rhine valley, I saw a crudely printed sign, painted with a whitewash brush, on the side of a building. ‘See the Rhine and leave your skull there,’ it said, and a skull and crossed bones were painted beneath the words to magnify the unsettling message.

“The two-and-a-half-ton gun trucks, pulling the battery’s four howitzers, whined in low gear as they made their way down the steep hill to the Rhine. As we towed the howitzers upriver, we passed a number of gray-painted landing craft parked beside the road on large, flat-bed trucks. Navy personnel in blue dungarees and hats accompanied the boats and we shouted jibes at the sailors, pointing out to them the general direction of the ocean and asking them if they were lost.

“The first gun section (truck, crew and howitzer) and our #2 gun truck and crew were loaded onto the first LCVP. As we left shore, we could see right ahead of us an island in the middle of the river and a castle on it that we later learned was called ‘The Pfalz.’”

Quick went on, “The current was very swift and carried us rapidly downstream as the propellers on our craft churned the muddy water, driving us forward at the same time. We passed the island on our starboard side and saw our landing site ahead of us, the paved sloping bank leading up to the village of Kaub.

“Our landing was without incident, but as we climbed the ramp to the village, we had to step over a dead German soldier, lying on his back at the top of the slope. There, beside his corpse, we waited for the next LCVP to bring us our #2 gun.”

The afternoon of March 26 saw six LCVPs again in action with the 89th Division’s crossing at Oberwesel. The initial transit was made in unprotected Army DUKWs and proved to be very costly in infantrymen losses. The division, having failed to establish a bridgehead, turned to the Navy and this time, along with the LCMs, the “swabbies” took over the operation.

Al Rust, also a member of the 89th, said that both the 53rd and the 354th Regiments were ordered to cross at St. Goarshausen and Oberwesel: “They both accomplished their objectives but only under murderous fire and with the loss of many men. The 1st Battalion, 355th (Task Force Johnson), was then directed to proceed north and cross the river in the 87th Infantry’s sector at the town of Boppard. We crossed the river on a ready-made Bailey bridge.

“On that day, March 26th, the 1st Battalion crossed the Rhine with Able Company in the lead followed by Baker and Charlie Companies. We were to proceed southeast through St. Goarshausen and head down the east side of the river toward Wiesbaden. Able Company soon ran into resistance south of Boppard in a small town called Kestert. One of Able Company’s rifle platoon leaders was killed here along with several of his men.”

Within 48 hours, the entire 89th, with all its vehicles and equipment, was carried across the Rhine. Patton was pleased with the 87th and 89th Divisions’ progress, because “All of the historical studies we had ever read on the crossing asserted that, between Bingen and Coblentz [sic], the Rhine was impassable. Here again we took advantage of a theory of our own, that the impossible place is usually the least well defended.”

The 358th Regiment of the 90th Infantry Division was attacked frequently by the Luftwaffe in the days after the crossing in a frantic effort to annihilate the bridgehead, but there was no stopping now, and the advance continued to the Main River where, on March 28, the 90th forced the crossing of the Main. The division would go on to seize the town Merkers in April and the salt mine there, capturing a fortune in the form of the Reich gold reserve and a storehouse of priceless art treasures, stolen by the Nazis from occupied countries.

Sixth Army Group’s Crossings

The 6th Army Group was originally created in Corsica, France, and activated on July 29, 1944, as “Advanced Allied Force HQ” a special headquarters within AFHQ (the headquarters of Henry Maitland Wilson, the Supreme Commander Mediterranean Theatre) and commanded by Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, a 1909 West Point graduate.

The group’s initial role was to supervise the planning of the combined French and American forces that invaded southern France in Operation Dragoon in August 1944 and provide liaison between these forces and AFHQ.

Dragoon was the operational responsibility of the Seventh U.S. Army commanded by Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch. Available to Patch were three corps: Frank Milburn’s XXI, Wade Haislip’s XV, and Edward Brooks’s VI (with a combined strength of nine infantry and three armored divisions), plus the French I and II Corps.

With Dragoon a success, and the ensuing march up France’s eastern border to the Vosges Mountains region and the subsequent plunge into southwest Germany having gone well, the time had come for the 6th Army Group to join with Bradley’s 12th Army Group and make an all-out thrust deep into southern Germany.

Devers directed Patch and his Seventh Army to spearhead the drive. It would be an onslaught that the Germans in the region had never seen before.

March 24: Seventh Army’s Crossing

South of Third Army’s crossings, Seventh Army prepared to cross at Worms with the XXI, XV, and VI Corps lined up north to south along the east bank of the Rhine. Thirteen anti-aircraft battalions also arrayed themselves in the Seventh Army sector to protect the assembled divisions and the engineers building the river crossings from the Luftwaffe.

Devers also told the 3rd and 45th U.S. Infantry Divisions, who were being held in SHAEF and Seventh Army reserve, to prepare to join XV Corps for an assault crossing of the Rhine at Worms. (The 11 divisions of Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s French First Army troops, many of them from France’s North African colonies, would also be added to the weight of the assault and would hit the Pforzheim Gap, west of Stuttgart and 18 miles south of Mannheim, but not until April 1.)

The 45th “Thunderbirds” had been teamed with the 3rd Infantry Division ever since the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, and had fought its way up to the Gustav Line and Monte Cassino, then took part in the bloodletting at Anzio. It finally helped liberate Rome and fought its way northward before being tabbed to take part in Operation Dragoon. It had then spent months fighting in eastern France and spent a miserable winter battling in the snowy Vosges Mountains before entering Germany.

The Thunderbirds, now under the command of Maj. Gen. William T. Frederick, the former head of the 1st Special Service Force (“The Devil’s Brigade”), were weary from nearly 500 days of combat but could, at last, see the end of the war looming ahead of them. If they could cross the Rhine, perhaps that would hasten the Allied victory.

Now, as part of Seventh Army and XV Corps, the 45th prepared for its crossing. In addition to its organic artillery, 15 battalions of light, medium, and heavy artillery were attached to the 45th, while the engineers of the 40th and 540th Engineer Combat Groups constructed support rafts, one heavy pontoon ferry, and one DUKW ferry in each assault regiment’s sector. The engineers were also tasked with building one heavy pontoon bridge, one floating treadway bridge, and one dummy bridge.

On March 24, the division command post moved up to Westhofen, northwest of Worms, and the next morning the advance assault units began crossing in a swirling, moonlit fog that hid the movement from the enemy.

Jack Hallowell, a soldier with the 45th, wrote, “Soon after midnight, the 179th and 180th Infantry Regiments launched the 45th Division attack across the Rhine. Crossing the quarter-mile stretch of water in assault boats, and with no protective artillery concentration preceding them, the troops took the enemy by surprise; it was not until the boats had been emptied and were returning to the opposite bank that intense mortar fire fell into the division sector.

“Though 50 of the boats were damaged, the main body of assault troops had gained the foothold which doomed the enemy position.”

As the assault boats scraped against the Rhine’s eastern bank, German forces opened up with rifles, machine guns, 20mm flak guns, and 88s. The 45th’s official history says, “In the face of strong initial resistance on the shore line, the assault troops leaped ashore on the low bank … then fanned out into the misty darkness to carve out a bridgehead.

“The initial resistance was strongest in the 180th Infantry Regiment’s sector, where more than half the assault boats in use by the 40th Combat Engineers were lost in the crossings.

“By dawn they were firmly established on the eastern bank, and by the close of day they had secured a bridgehead 104 square kilometers in size…. The Air Corps furnished a canopy of protection throughout the entire operation.”

George Fisher, author of the 180th Infantry’s regimental history, said that his regiment assembled in the vicinity of Wachenheim on March 23 and prepared their weapons for the big day. Shortly after midnight on the 25th, a four-man patrol [led by a lieutenant colonel] set out across the river from the village of Rhein-Durkheim in an inflatable rubber boat.

“Once on the east bank,” Fisher said, “they penetrated the German-held ground for 40 minutes and plotted German installations and estimated the enemy strength.

“The patrol … had located the German position so accurately that troops of the battalion … were able to get past the beach defenses that consisted of 14 flak guns and 100 men manning machine guns and small arms.”

At H hour on the 25th, after the main body had launched, the German fire from the east bank was intense. One of the assault boats flipped over, throwing the men into the cold and swift-flowing water. When one soldier with a heavy radio strapped to his back appeared on the verge of drowning, a buddy went to his rescue and, removing the radio, helped him get to shore safely.

In the dark on the east bank, one sergeant approached a group of men he thought were Americans but they turned out to be Germans and they took him prisoner. Moments later, several other Americans in the 180th came upon the scene, killed the Germans, and freed their sergeant.

Warren P. Munsell, Jr., a member of the 45th’s 179th Regiment, wrote, “At 0230, March 26, the engineers pushed the storm boats over the crest of the bank. Sergeants gathered their squads together, shadowy figures in the deep shadows of the trees. As the assault boats slapped into the racing tide, the troops piled in, and the 1st and 2nd Battalion men began to cross.

“The enemy cut loose with a furious small-arms crackle from the eastern bank. T/Sgt. Llewellen Chilson saw his platoon leader take a slug as the boats neared the enemy bank, and realized that he was now in command of a platoon in G Company.

“Heavy German SPs [self-propelled artillery] let fly at the tiny boats swarming toward the eastern edge of the river. Then the Americans hit the bank, scrambled over the rise, and poured down on the German machine-gun nests. Rifles cracked, carbines spit back, German burp guns spoke in dribbling bursts.

“Chilson’s platoon met small-arm, then machine-gun, fire. Several men fell. Sgt. Chilson signaled his men to halt, then crawled up the bank of the dike and wiped out two nests single-handedly with white phosphorus grenades and his carbine. His platoon followed and picked up 23 kraut prisoners.

“By 0330, both the 1st and 2nd Battalions had all their foot elements across and, overrunning the German defenses after a few desperate, costly moments, were driving inland.”

Munsell also noted that, as it grew light, Company G was moving out of a small village when the men were “suddenly mowed down by two flak wagons turned into anti-personnel weapons set up at opposite ends of an open field to catch the Yanks in a deadly crossfire. The Air Corps bombed and strafed the guns.”

Small groups of the enemy, sometimes supported by panzers, attempted to halt the incursion at the water’s edge—an attempt as deadly as anything encountered by Allied troops at Normandy—but they were repulsed each time by the Yanks and hundreds of Germans were killed or taken prisoner. Well-deserved Bronze and Silver Star medals and DSCs would be the reward for the acts of heroism the Americans performed that morning and in the days that followed. Even chaplains and medics were decorated for ignoring the danger to help their fellow Americans.

Simultaneously with, and south of the 45th’s crossing, the 3rd Infantry Division, which had been under the command of Lucian Truscott, Jr., for most of the war and now was led by Maj. Gen. John W. “Iron Mike” O’Daniel, began its assault after a 12,000-round artillery barrage of the eastern shore at Sandhofen, between Worms and Mannheim-Ludwigshafen.

Charles Smith, 3rd Division, recalled, “When we got to the Rhine, the Navy brought in 22 assault boats. We piled into the boats; there were 22 of us in the first two. We got to the German side of the river and the Germans sunk all the rest of the boats. So 22 of us were on one side of the river with the whole German army and the rest of our boys were back at the start.”

Lawrence “Larry” Bennett, also a member of the 3rd, had survived combat from the landings in Italy to the Vosges Mountains but was wounded in December 1944. After spending four months in army hospitals, he returned to his unit on the night it was crossing the Rhine River. “I stayed with the motor pool that night,” he said, “and joined my outfit the next morning, crossing the Rhine on my 21st birthday. White flags were on the houses in Germany.”

The last river crossing was made on short notice opposite the city of Mainz early on March 28 by the XX Corps’ 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division packed into 12 LCVPs and six LCMs. The 80th tried what the 89th had attempted and was also initially unsuccessful.

The first assault wave, in 20 Army assault craft at 1 a.m., was virtually wiped out. At 3:30 a.m., the Army officer in charge suspended the crossing operation.

Naval Reserve Ensign Oscar Miller, however, was not informed of the suspension. He launched the first LCVP across the river that landed 500 yards below the planned line of departure. It met with no enemy resistance and the other boats were then launched, all with no casualties.

In three hours, 3,500 men successfully crossed, but at 7 a.m. German artillery saturated the launching site and scored a direct hit on a bulldozer, demolished several trucks on shore, and killed Lieutenant (j.g.) Vincent Avallone, the only Navy fatality during the entire operation. Still, work went on unabated with the boat crews and support personnel working six-hour shifts without respite for three continuous days.

Robert T. Gholson, a member of the 80th’s 313th Field Artillery Battalion, wrote a history of his unit, referring to himself in the third person: “March 27: This day the rain fell as the 313th Field Artillery Battalion moved nine miles, stopping at the town of Mainz—only two miles from the Rhine River.

“March 28: The 313th Field Artillery Battalion fired concentration across the Rhine all day long. The 105mm howitzers were clearing out any remaining German forces on the opposite side of the river. The 317th Infantry crossed the Main River and cleared out the town of Wiesbaden. Along the way they captured factories, airstrips, ammunition-storage depots, and a champagne factory filled with 4,000 bottles of the wine.

“Word of the 317th’s champagne victory the day before had spread fast. The men of the 317th Infantry made sure that their friends (the artillerymen in the 313th Field Artillery Battalion), who had supported them for so many months, didn’t miss out on the ‘bubbly booty.’ That evening Gholson and his buddies celebrated hard and officers looked the other way.

“March 29: Gholson and the 313th Field Artillery Battalion made their way to the river crossing arriving at 6:30 p.m. Battery B’s trucks and guns drove across the huge pontoon bridge constructed by the engineers a few days before. The whole area was encased in smoke from canisters set off to shield the Americans from view as they crossed. The smoke was so dense that, after they crossed to the east side, they couldn’t see but 10 or 15 feet in front of themselves. The 313th traveled another few miles after the crossing to Wiesbaden.

“March 30: The 313th Field Artillery Battalion continued to move forward. This day Gholson and his buddies drove past a makeshift cemetery under construction. They were shocked to see about 100 dead bodies lying nearby, dead civilians and German soldiers.”

By March 27, the 80th Division’s 317th Regiment was preparing for a crossing of the Main River at Mainz the next morning, but Major James Hayes of the 2nd Battalion was shocked to learn that the field order had eliminated the preparatory artillery fire in an attempt to achieve surprise.

He argued with Lieutenant Colonel August Elegar, the division operations officer, that the troops could not surprise the enemy because of the wide-open terrain and a full moon, but Maj. Gen. Horace McBride, the division’s commander, would not change the order.

As Hayes feared, the moonlight made the soldiers excellent targets for German artillery and small-arms fire that zeroed in on the crossing of the troops of the 2nd Battalion. Lieutenant Frank, a platoon leader in G Company, was killed during the crossing. Hayes said that he was one of the original enlisted soldiers of G Company and had earned a battlefield commission due to his outstanding performance. Hayes blamed his death, along with many others, on the lack of preparatory artillery fire.

When the soldiers eventually reached the east bank, enemy resistance lasted a mere 15 minutes and then the Germans began to surrender en masse. By the time the second wave of G.I.s landed, all opposition had ceased and the soldiers moved on to Wiesbaden.

Advance to the East

At a press conference in Paris on March 28, General Eisenhower praised the Allies’ work along the Rhine. After acknowledging Montgomery’s victory in the north, he said, “The success of those operations was due to the extraordinary preparation and skill and drive of General Bradley’s armies, coupled with the tremendous power of General Devers’ thrust—the Seventh Army under General Patch, and to which were attached also a French group called the Group Monsaberg, on the right—were able to put in from the south.”

Over the next few days, Bradley’s armies that had reached the east side of the Rhine engaged the determined enemy in a series of battles large and small—in tiny hamlets and major cities, in farmers’ fields and along highways.

Some scenes were startling. GIs were surprised to find various towns with Esso gas stations of the Standard Oil Company in their streets—a touch of home. Many of the houses that hadn’t been destroyed were elegant and exquisitely furnished. A 45th Division soldier said that one residence had 83 sets of deer antlers fastened to the walls. Another said he slept in a real bed for the first time in months.

Still to be fought for and taken were scores of German towns and cities—Frankfurt-am-Main, Aschaffenburg, Nuremberg, Munich, and many more. The end of the war was only a little more than a month away, but no one knew it.

Yet, for those men who died along it, the road to victory might have been a million miles long. Their sacrifice was no less great—and their contribution no less important—than that of the men whose lives were cut short in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Anzio, Normandy, the Riviera, or anywhere else. Their loved ones would forever mourn them and honor their memory.

Patton’s bold move had taken the wind out of Montgomery’s sails, but the British field marshal nevertheless went ahead and executed his carefully laid plans, starting on March 24, with a British and Canadian force of 26 divisions, four armored brigades, and a separate commando brigade. Two airborne divisions were standing by at their aerodromes to be dropped east of the Rhine once the amphibious crossings had begun between Arnhem and Dusseldorf, just north of Simpson’s First U.S. Army.

The 180th Regiment’s Warren Munsell wrote, “Seventh Army’s Rhine crossing was a success. Hotly contested by the enemy, especially in the 3rd Division sector to our south, nevertheless the veteran divisions had done their job swiftly and surely.

“They had swept inland at many points so rapidly after crossing the Rhine that whole companies of Germans had been caught flat-footed and surrendered. Japs might lose their necks to save face, but Germans were perfectly willing to lose face to save their necks.”

Which bridge is shown in the initial part of the article? Some years I saw one that resembled it on the Main River upstream for Aschaffenburg/downstream from Wurzburg.

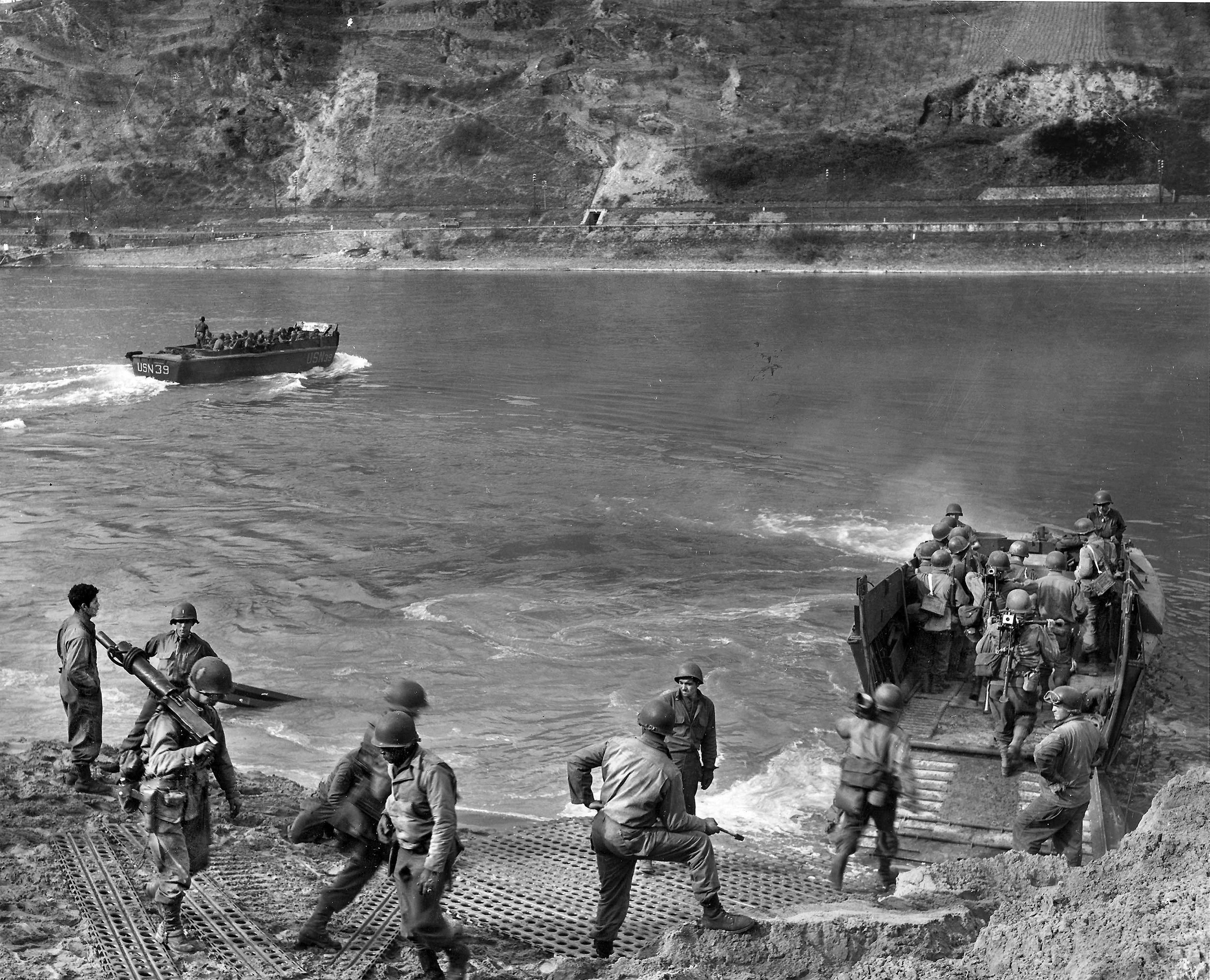

Troops of the 4th U.S. Infantry Division cross the Rhine River at Worms, March 26, 1945.

Thanks from an old 7th Army/USAREUR guy.

“…I crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim, stopping to spit in the river.”

I have read elsewhere that it was a different, yellowish, bodily fluid that was, shall we say, expelled into the Rhine by Patton & Co.

There is a photo of Patton urinating into the Rhine. Or, at least, he’s posing as if he’s doing that. You can find the photo in this story:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/george-s-pattons-end-run-the-story-of-his-final-days/

When did the 29th Infantry Division cross?

The commander of the 45th Infantry Division is Robert T. Frederick vice William T. Frederick.