By Major General Michael Reynolds (ret.)

“In the years to come everyone will remember Arnhem, but no one will remember that two American divisions fought their hearts out in the Dutch canal country,” wrote U.S. Air Force Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, commander of the First Allied Airborne Army, shortly after Operation Market-Garden. Sadly, his prediction proved all too accurate. Many books have been written about the fighting in the Arnhem area, but few about the actions of the two American airborne divisions involved in this operation.

Choosing the Ruhr Over the Saar

By the beginning of September 1944, the Allied advance toward Germany had been halted due to a lack of supplies, particularly fuel. As General George Patton is alleged to have said, “My men can eat their belts, but my tanks have gotta have gas!” No major port east of the Seine River had been captured, the British supply lines stretched 500 km, all the way back to Bayeux, and those of the Americans ran even farther, 600 km, through Paris to the Cotentin Peninsula.

In addition to the supply problem, there was at this point in the campaign a serious argument between the Allied leaders over whether to proceed on a broad front, with Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group advancing in the north toward the Ruhr and General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group moving at the same time in the south toward the Saar, or in a single thrust by just one of the Army Groups.

The relative merits of each case have been set out clearly in the many books describing the strategy of the European campaign. On September 4, 1944, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a directive ordering Montgomery’s Army Group and two corps of the First U.S. Army to “reach the sector of the Rhine covering the Ruhr and then seize the Ruhr.” At the same time, the Third U.S. Army and one corps of the First U.S. Army were to “occupy the sector of the Siegfried Line [West Wall] covering the Saar and then seize Frankfurt.”

This directive, while apparently giving Monty a green light, presented him with a problem. Surprising though it may seem, he had insufficient forces to exploit the German weaknesses on his front. Of the 14 divisions and seven armored brigades in his 21st Army Group, only two armored divisions of XXX Corps were ready to continue the advance. The six Canadian divisions had been given the essential task of clearing Le Havre and the Pas de Calais ports, XII Corps was committed to pushing the German Fifteenth Army back to the Scheldt Estuary, and VIII Corps was still immobilized back at the Seine owing to a lack of transport.

Nevertheless, XXX Corps was told to push on, and on September 4, the 11th Armored Division captured Antwerp. Then, late on September 10, an armored group secured a bridgehead over the Albert Canal at Neerpelt, and the foothold required by Monty for his single thrust toward the Ruhr was a reality.

That same afternoon, Montgomery and Eisenhower met at Brussels airfield. After an acrimonious opening discussion, during which Ike had to remind Monty that he was a subordinate, the supreme commander eventually approved the latter’s latest plan. This envisaged the First Allied Airborne Army, Eisenhower’s only strategic reserve, securing crossings over the Maas, Waal, and lower Rhine Rivers, and then British armor advancing rapidly to outflank the West Wall and the Ruhr. The plan had the added advantage that, if successful, it would cut off all the Germans in western Holland, including the Fifteenth Army. Monty gave the go-ahead for Operation Market-Garden to be launched on September 17.

“Like Coins Burning in SHAEF’s Pocket”

The First Allied Airborne Army was under the command of General Brereton, formerly the commander of the U.S. Ninth Air Force. His deputy was British Lt. Gen. “Boy” Browning, and he had a mixed staff of Americans, British, and Poles. Brereton’s army had two corps, one American and one British. The XVIII U.S. Airborne Corps, under Lt. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, comprised the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. The 82nd and 101st were battle-experienced divisions, the 82nd having dropped and fought in Sicily and both having dropped and fought in Normandy. The I British Airborne Corps, under the command of the “double-hatted” General Browning, consisted of the inexperienced 1st British Airborne Division and the equally inexperienced 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group.

The soldiers of the First Airborne Army were “like coins burning in SHAEF’s pocket.” Since early July, most of them had been on standby for a whole series of operations, none of which had been launched, either because the ground troops had moved so quickly that the proposed operation became redundant or because the necessary aircraft were being used for aerial resupply. It was, therefore, with relief and enthusiasm that Brereton and his staff began their planning to employ three and one-third airborne divisions, to be dropped in three different areas and, hopefully, to be relieved within three days by the ground troops of the British XXX Corps.

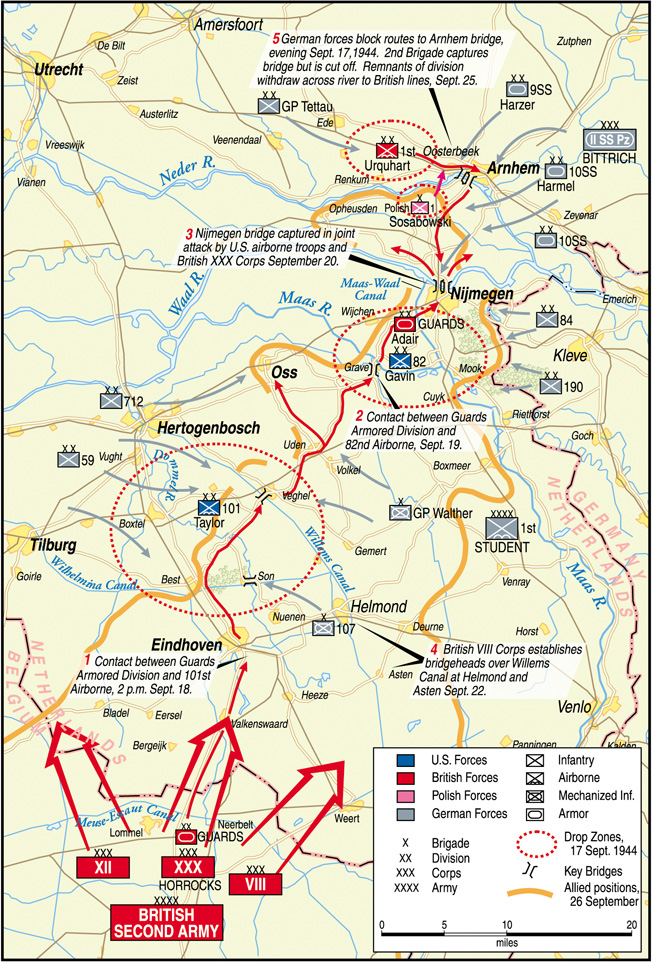

The aim of Operation Market-Garden was to capture and hold the five major crossings over the canals and rivers lying across the British Second Army’s axis of advance between and including the Dutch towns of Eindhoven and Arnhem. Command was vested in the British deputy commander of the First Airborne Army, Lt. Gen. “Boy” Browning. The decision to give him command was surprising for three reasons: First, because 75 percent of the troops taking part in the operation were to be American; second, because the U.S. Corps commander, Ridgway, was far more experienced; and third, because Browning’s headquarters was basically a planning, administrative, and training organization and certainly not a command headquarters.

Inevitably, Browning’s headquarters had no means of communicating with the two American divisions, and this meant that U.S. manpower and equipment had to be added to it at the last minute. In the event, Browning and his headquarters, due to totally inadequate communications, played little part in the forthcoming battle and wasted 38 gliders badly needed by the 1st British Airborne Division to increase its first lift.

The Trouble With Operation Market-Garden

The basic plan was for the 101st Airborne Division to seize the several bridges and defiles between Eindhoven and Grave. The 82nd Airborne was to capture the Maas crossing at Grave, at least one of the four bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal, and then, after securing the high ground between Nijmegen and Groesbeek, to capture the vast Waal road bridge in Nijmegen. At the same time, Maj. Gen. Roy Urquhart’s 1st British Airborne Division, later aided by Maj. Gen. Stanislaus Sosabowski’s 1st Polish Independent Brigade Group, was to capture “the bridges over the lower Rhine at Arnhem with sufficient bridgeheads to facilitate the passage of XXX Corps.”

The XXX Corps’ Operation Instruction included the prophetic words, “The success of this operation depends largely on speed of advance.” Nevertheless, the problems and dangers of sending a complete corps of over 20,000 vehicles down a narrow corridor on only one proper road, across a series of six major canals and waterways, to link up with an airborne bridgehead 100 km away were all too obvious.

It will not have escaped the reader’s notice that the extent of the missions given to the American divisions was infinitely greater than that given to the British and Poles. The latter had to hold on for a longer period, but at least their operational area was limited in size. In an attempt to deal with this problem, the Americans reinforced each of their divisions with an extra regiment, giving them four rather than the normal three. Even so, the sheer magnitude of their operational areas virtually guaranteed that the Americans would have problems holding them until they were relieved.

The risks inherent in Operation Market-Garden are well known. Put simply, they were: (1) the weather, (2) insufficient aircraft and gliders to carry out all the landings in one lift, and (3) carrying out the assault in daylight. The air commander for the operation, U.S. Maj. Gen. Paul L. Williams, commander of IX Troop Carrier Command, USAAF, decided, with Brereton’s support, that no more than one lift should be flown each day.

This was due not only to the difficulties of navigating and keeping formation in the predawn or post-dusk flights that would have been necessary if two separate lifts had been launched in a single autumn day, but also to there being insufficient ground staff to turn around and repair aircraft in the time available. The effect of this decision was that three consecutive days of good flying weather would be needed to land the whole force.

Improvised German Resistance

In the early afternoon of September 4, General Kurt Student, the head of the German parachute arm, was telephoned in his Berlin office by General Alfred Jodl, head of the High Command Operations Staff, and told that he was to command a new army to be known as the First Parachute Army. Its mission was to build and hold a new defensive front on the line of the Albert Canal in northern Belgium. He was then told that General von Zangen’s Fifteenth Army of over 80,000 men was isolated in northeast Belgium and could escape only by sea across the Scheldt Estuary.

Even if this were achieved, it would take at least three weeks and heavy losses were likely.

Furthermore, the remnants of the Seventh Army were being pushed rapidly toward the Ardennes Forest, and the only troops available to deploy into the resulting 120 km gap along the Albert Canal between Antwerp and Maastricht were those of a division badly depleted in the Normandy fighting and a fortress division that had been guarding the Dutch coastline.

Another division, composed of convalescents and men who had been invalided out of the Army and then brought back, was currently entraining at Aachen in Germany and would be available in two or three days. Student’s First Parachute Army was therefore to comprise all garrison, training, and administrative troops already in Holland, the divisions just mentioned, and a new force of some 30,000 Luftwaffe personnel. The latter had been volunteered by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring and consisted of six parachute regiments in various stages of training or re-equipping, and some 10,000 Luftwaffe air and ground crew whose operations or training had been curtailed because of fuel shortages.

By any standards, what followed was an incredible feat of improvisation and organization. The precise details are complicated. Suffice it to say that by September 13, General Student had established a defensive line, albeit fragile, from the mouth of the Scheldt to Maastricht behind which further battlegroups or Kampfgruppen (KGs) could be formed and deployed. This line was manned by a mere 32 ad hoc battalions, backed by 25 assault guns.

It was while this basic defense structure was being established that, on September 8, the last elements of Willi Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps arrived in central Holland. This corps had been badly mauled in the Normandy fighting and had been sent to Holland to lick its wounds and be refitted. In fact, the corps’ two divisions, the 9th SS Panzer Hohenstaufen and 10th SS Panzer Frundsberg, numbered little more than 6,000 to 7,000 men each at this time, of whom only about half were combat troops. Nevertheless, the Hohenstaufen was to be heavily involved in the Arnhem fighting and the Frundsberg in the Nijmegen battle. From the point of view of this narrative, it is important to note that by the time the Allies landed, two Hohenstaufen panzergrenadier battalions and three batteries of artillery had been transferred to the Frundsberg. One of the grenadier battalions, SS Battalion Euling, named after its commander, SS Captain Karl-Heinz Euling, was to play a major role in the Nijmegen fighting.

Soon after his arrival in the Arnhem area, the Frundsberg commander, SS captain Heinz Harmel, was ordered to provide a strong KG as a reserve for the First Parachute Army. The KG was named KG Heinke, after its commander SS Major Heinke. It comprised two SS panzergrenadier battalions, companies from the Frundsberg’s reconnaissance and Pioneer battalions, and an artillery battalion. Arriving south of Eindhoven on the 10th, Heinke took under command the Frundsberg’s SS panzerjäger battalion, with 21 Jagdpanzer IVs and a company of 12 40mm towed antitank guns, which was already in the area. His KG would also play an important part in the forthcoming fighting.

Field Marshal Walther Model, commander of Army Group B and the overall commander in the area, set up his headquarters on September 15, just two days before the opening of Market-Garden, in the Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek, a mainly residential area of about 10,000 people a few kilometers to the west of Arnhem. It was sheer coincidence that he found himself less than 4 km from one of the main British landing zones (LZs) and that the units of the Hohenstaufen and Frundsberg Divisions were within 50 km of all the Allied LZs.

Operation Market-Garden

Operation Market-Garden began during the night of September 16-17, with 200 RAF Lancaster heavy bombers and 23 Mosquito fighter-bombers attacking four airfields in the general area of the proposed drop zones.

Shortly after first light, 54 more Lancasters and five Mosquitoes attacked known flak positions while a further 85 Lancasters and 15 Mosquitoes pulverized the German coastal batteries on Walcheren. Then, just before the troop-carrying aircraft flew in, 816 U.S. B-17 heavy bombers, escorted by 373 P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, attacked an additional 117 known flak positions on the approaches to and near the LZs.

The airborne armada, protected by 919 fighter aircraft, including Tempests, Spitfires, Mosquitoes, Thunderbolts, Mustangs, and Lightnings, comprised 1,544 troop-carrying aircraft and 478 gliders. Beginning at 1025 hours, they took off over a period of 11/2 hours from 17 U.S. and nine British bases in England.

Inevitably, reports of hundreds of Allied aircraft flying northeast began to arrive at the various German headquarters, but surprisingly few of the duty officers on this warm, sunny afternoon appreciated their significance. One senior officer who did was the commander of II SS Panzer Corps, SS Maj. Gen. Bittrich. He received his first enemy situation report at 1330 hours (German time) and 10 minutes later issued a warning order to both his divisions.

The Hohenstaufen was told to assemble its units for operations to secure Arnhem and its bridge and engage enemy air landings to the west of the city. The Frundsberg was told to assemble for an immediate move to Nijmegen, where it was to occupy the bridges over the Waal and then advance to the southern edge of the city. The Nijmegen sector and the 82nd Airborne Division’s LZs became the immediate task of Military District VI. This was an administrative command, totally unsuited for controlling combat operations. Nevertheless, its commander was promised additional troops in the form of a complete parachute corps, which would be brought from Cologne.

While the British were heavily engaged in the Arnhem area 20 km to the south, 7,277 paratroopers and 48 gliders of the 82nd Airborne Division, under the command of Brig. Gen. James Gavin, had landed successfully. Lt. Col. Reuben Tucker’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, led by E Company of the 2nd Battalion, captured the vital bridge over the Maas at Grave, while other troopers of the regiment secured another over the Maas-Waal Canal. These actions were completed by 1930 hours.

This meant that as soon as the British armor arrived, it would be able to advance straight toward Nijmegen. Meanwhile, the 505th and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments, together with the divisional engineer battalion and an artillery battalion with 12 75mm howitzers, occupied the strategically vital ground around and to the southeast of Groesbeek. Owing to the enormity of the task, however, the majority of these defensive positions were little more than platoon-sized roadblocks. The original orders to the 82nd Airborne specified that no attempt be made to take the main Nijmegen road bridge until the bridge over the Maas, at least one of those over Maas-Waal Canal, and the high ground covering the approaches from Germany at Groesbeek had been secured. Indeed, control of the Groesbeek feature was considered vital to the success of the whole Grave-Nijmegen operation. Accordingly, General Gavin had briefed Colonel Roy Lindquist, the commander responsible for the Groesbeek area, that he should only send a battalion against the Nijmegen road bridge if the situation in the Groesbeek area was in hand, and then only under the cover of darkness.

By 1800 hours the situation seemed favorable enough, and at 2200 hours the move toward the bridge began. Three companies from two separate battalions were committed, but the two leading companies of the 508th ran into heavy opposition in the area of the main traffic island in the city, and their advance halted. The Nijmegen road bridge itself was defended by a scratch force of about 750 men from various training and reserve units in and around the city, cobbled together by a Colonel Henke, the commander of a spare parachute training regimental headquarters—another perfect example of German initiative and military competence. Henke also ensured that the 29 88mm flak guns and some additional 20mm weapons, sited to protect the road and rail bridges, were capable of firing in a ground-support role.

The third component of Operation Market-Garden, Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne Division, had also been largely successful in fulfilling its missions. Within a few hours, nearly 7,000 troopers of its three parachute regiments had captured the towns of Veghel and St. Oedenrode and all but one of the bridges in the 25 km cor- ridor between Eindhoven and Veghel. This corridor eventually became known to the Americans as “Hell’s Highway.” The only important bridge not to be captured was the one at Son (sometimes spelled Zon) over the Wilhelmina Canal. A KG from the Hermann Göring Training Regiment had managed to hold on long enough against part of Colonel Robert Sink’s 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment for it to be blown at about 1600 hours. Nonetheless, during the night the Americans swam or crossed the canal in small boats and overcame the opposition. A makeshift wooden footbridge, based on the remains of the original metal bridge, was then constructed by the airborne engineers, and soon after dawn the men of the 506th were approaching Eindhoven, where they were expecting to link up with the British armor coming up from the south.

The British Halt at Valkenswaard

It will be remembered that Field Marshal Model had given General Student’s First Parachute Army the task of dealing with this airborne assault. Accordingly, three combat groups were deployed: first, the leading elements of the very understrength 59th Infantry Division of the Fifteenth Army (some 3,000 men), having escaped across the Scheldt, were ordered to detrain at Tilburg, only 25 km northwest of Eindhoven, and advance toward the Best sector of the Wilhelmina Canal. Second, two scratch battalions of paratroopers from a training and reinforcement unit a similar distance north of Eindhoven were ordered to advance toward the 101st’s bridgeheads at St. Oedenrode and Veghel. Third, Panzer Brigade 107, with a battalion of Panther tanks, a panzergrenadier unit in SPWs (armored personnel or weapons carriers), and a company each of Sturmgeschütze (armored assault guns) and SPW-mounted Pioneers, was diverted from the Aachen area. It was expected to arrive in the area in just over 24 hours.

The first of these groups to see action was part of the 59th Division, which, during the afternoon and night of the 17th, thwarted H Company of the 506th Parachute Regiment in its attempt to seize a bridge over the canal near Best.

What of the British advance toward Eindhoven? Although it was supported by a massive artillery barrage and plenty of close air support, the leading brigades of XXX Corps had been ordered to halt at Valkenswaard after an advance of only 12 km. This happened at 2200 hours on the grounds that the leading armored group “had been fighting hard and tanks require maintenance.” Incredibly, the advance was not to continue until 0700 hours the following morning. One Guards officer later wrote: “We should never have stayed the night in Valkenswaard but should have continued to advance all night to Eindhoven and beyond non-stop…. It made no sense to stop, bearing in mind the distance to be covered to Arnhem and the river crossings ahead.”

The German Counterattack

The first German troops to make contact with the force already protecting the Waal bridges in Nijmegen, KG Henke, were those of a Major Reinhold’s Frundsberg SS Panzergrenadier Battalion and a party of Pioneers. The Pioneers immediately started preparing the massive road and railway bridges for demolition, while Henke briefed Reinhold on his defensive layout. After being told that a scratch force was already defending a line running approximately a kilometer south of the Waal bridges and that two 20mm and one 88mm flak gun were covering the Waal railway bridge, Reinhold decided to deploy his men on the north bank of the river immediately adjacent to the bridges.

Next to arrive, at about midday, was Captain Euling’s Hohenstaufen SS panzergrenadier battalion which had been attached to the Frundsberg. Reinhold gave orders that it was to secure the immediate approaches to the road bridge and placed the various Army and police detachments already manning strongpoints in the area under Euling’s command. The latter set up his command post near the Valkhof, the citadel of Nijmegen and the highest point in the city, not far from the southern ramp of the bridge, while his men took up positions covering all the approaches to the large traffic island near the south end of the bridge.

This was the same traffic island where the leading companies of the 508th had been halted the previous evening. Four Sturmgeschütze were also allocated to Euling. They had crossed the Rhine at Pannerden where, since early that morning, the Frundsberg Pioneers had constructed a ferry service. Meanwhile, on the north bank, Reinhold ensured that the 88mm flak guns, already protecting the bridges from air attack, were re-sited among the houses at the water’s edge so that they could engage with direct fire any vehicles attempting to cross. As further Frundsberg units arrived, including a few Mk III and IV tanks, they were incorporated into the overall defensive system and used to strengthen KG Henke. Mines were laid and various buildings, including factory chimneys and even church towers, were demolished to create obstacles.

What of the Americans during this time? Brig. Gen. Gavin knew full well that until the arrival of his second lift he did not have the strength to hold the vital Groesbeek area and at the same time mount a strong attack on the Nijmegen road bridge. To compound his problems, the abortive attempt to take the bridge the previous night had depleted his forces covering the LZs and the approaches from the Reichswald. There were, however, two factors in his favor. First, there were, and still are, no roads or even reasonable tracks leading from the Reichswald toward the thickly wooded high ground at Groesbeek. Second, the Maas-Waal Canal and waterways flowing into the Waal just to the east of Nijmegen channeled any German attack toward the Groesbeek ridge.

At 0630 hours on the morning of the 18th, the Germans launched their long-awaited counterattack. In another amazing feat of inventiveness, organization, and military competence, they had assembled an ad hoc force of four battalions armed with 24 mortars and 130 light and medium machine guns, three artillery batteries, and even a few armored cars and SPWs mounting flak guns. Totaling over 3,000 men, many of whom had never received even basic infantry training, this group, designated the 406th Division, was ordered to attack and drive the Americans back across the Maas.

In view of the very thin American defenses, it was perhaps not surprising that the German attacks made some progress and parts of the LZs were overrun. With the expected fly-in not due until 1300 hours, Gavin was forced to withdraw his men from Nijmegen and throw in his last reserves—two companies of the 307th Parachute Engineer Battalion. Even so, fighting was still going on when the first of 450 Dakotas, towing 450 gliders, appeared overhead at 1400 hours. Bad weather in England had delayed their take-off.

Although some casualties were suffered, the fly-in, which included 18 howitzers and eight 57mm antitank guns, was amazingly successful and caused panic among the Germans, who fled. Ninety-seven close air support sorties were flown during this action.

The Americans had suffered few casualties during the day, but the German counterattack and the late arrival of his reinforcements had ended Gavin’s chances of mounting a proper attack against the Nijmegen bridges. His best hope now was a combined attack with the British armor, which he was told was due to arrive at the Grave bridge at 0830 hours the following morning.

First Contact With British Armor

At 0700 hours on September 18, the British 5th Guards Armored Brigade resumed its advance toward Aalst. The only immediate opposition at this time was the depleted remnants of a KG that had resisted the advance the previous day and one or maybe two Jagdpanzer IVs operating on the eastern flank of the Eindhoven road. Even so, with close air support unavailable during the first part of the day due to poor flying weather, it took until midday for the leading British battle group to cover the 5 km to Aalst.

Then, just to the north of the village, four 88mm guns were encountered covering another waterway and the approach road to Eindhoven. Armored cars managed to bypass this opposition to the west, and in an attempt to exploit this opportunity the reserve battle group was told to follow up. However, the weakness of the bridges in the area frustrated the advance of the heavier tanks and it was a further six hours before the leading elements of the division covered the last 2 km to Eindhoven and made contact with the U.S. 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment already in the city.

Eindhoven itself was undefended, and one young Guards officer later wrote: “On the outskirts of Eindhoven we passed our first American soldier standing at the side of the road and holding the hand of a small child. He waved and shouted, ‘Great stuff, boys.’ More and more Americans appeared, strolling round the town. It was surprising to see them in an almost peacetime atmosphere. There were no barricades at main roads, machine-gun posts, antitank guns, or other static defences.”

The British tanks reached the Wilhelmina Canal at Son at 2100 hours, and Royal Engineers arrived shortly afterward to begin bridging the gap. Fortunately, a heavy German bombing attack on Eindhoven during the night did not interfere with this work and by 0615 hours on September 19, a 40-ton Bailey bridge was spanning the Wilhelmina and the tanks of the Guards Armored Division were ready to continue their advance.

In the meantime, a major battle had developed at Best where, it will be recalled, men of Lt. Col. John Michaelis’s 502nd, H Company in particular, had been struggling to capture the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal. Unfortunately, elements of the 59th Division of the Fifteenth Army proved too strong and at midday on the 18th the bridge was blown. Moreover, the continuing buildup of this division now began to pose a serious threat to the 101st’s tenuous hold on Hell’s Highway.

The bad weather in England affected the fly-in of the American follow-up troops. The IX Troop Carrier Command launched a total of 445 aircraft and 385 gliders on the 19th, of which 27 aircraft were lost and only 221 gliders reached their LZs. The failure to launch 258 of their gliders, carrying the 82nd Airborne Division’s 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, was to end any hope Brig. Gen. Gavin might have had of capturing either of the vital Nijmegen bridges on this day. Just as bad, only 40 of the 265 tons of essential stores and ammunition destined for his division were recovered.

Arrival in Nijmegen

The British began their advance from Son at 0615 hours and at 1100 hours reached the Grave bridge, where their commander was met by Lt. Gen. “Boy” Browning, the airborne corps commander, and Brig. Gen. Gavin. Browning said he believed that a concerted rush could succeed in capturing the Nijmegen road bridge and, after a short conference, it was agreed that Gavin would place the 2nd Battalion of the 505th under British command for this mission. As a quid pro quo, the British gave Gavin a mixed battle group of tanks and infantry to help him defend his vital 40 km perimeter facing the Reichswald. He said later, “So far, we had been spared a German armored attack, but now, with the availability of British armor, we felt equal to anything that could happen.”

The advance into Nijmegen by three combined columns began at 1600 hours. The smallest group, made up of a British infantry company and four tanks, was given the main post office as its objective in the belief that it contained the demolition control point for blowing the bridges. It was captured without difficulty, but nothing was found.

Stronger, simultaneous attacks were launched against the men of KG Euling defending the road bridge and KG Henke at the rail bridge. The road bridge attack was carried out by the 2nd Battalion of the 505th, less a company, but with 12 British tanks and a British infantry company attached. The attack against the rail bridge was taken on by single British and American infantry companies and 12 British tanks. Neither was successful. A German historian, Wilhelm Tieke, gives the German version of what happened: “Heavy fire burst from all the houses and parks around the two bridges over the Waal against the attackers. On the approaches to the railroad bridge, several Shermans were knocked out by an 88mm. At the highway bridge they did not get anywhere near as close. Twenty millimeter flak hammered the length of the streets and two StuGs attacked from well-concealed ambush positions and shot up several enemy tanks. With the fall of darkness, the infantry attack was repulsed. The American paratroopers and British tanks took positions for the night 400m from the bridges.”

A British liaison officer with the Americans in forward positions overlooking the bridge from its east side later wrote: “The plan had been to rush the bridge with the Grenadier Guards Motor Battalion but this failed as German SS troops and others were holding both ends of the bridge and the northern part of the town in strength…. The Grenadiers, together with the Americans, fought on all afternoon and after very bitter fighting reached a roundabout just short of the bridge where they were finally held up. These American troops are splendid types, brave and cheerful, and seemingly indifferent to the worst.”

Late in the day, the commander of XXX Corps, Lt. Gen. Horrocks, came forward and met Gavin, Browning, and Maj. Gen. Adair, commander of the Guards Armored Division. They were all acutely aware that the attempts to take the bridges had failed and that, with the Germans on both banks, their men had little chance of capturing either intact. It seemed obvious that, rather than risk losing a bridge, the Germans would demolish it. In fact, in the case of the road bridge, Field Marshal Model had expressly forbidden such an act. He was determined to use it in a counteroffensive.

The Allied commanders were now facing a crisis. The British force at Arnhem was in deep trouble, the 82nd Airborne Division’s eastern perimeter was under heavy pressure, and the extremely narrow XXX Corps corridor was under ground attack from both flanks and intermittent air attack. In similar circumstances, most commanders would have given up trying to fight their way to the bridges through a built-up area and would have carried out a river crossing on one of the flanks, followed by a bridging operation. These were far from normal circumstances, however, and the time needed to mount and carry out such complicated operations would have spelled annihilation for the British at Arnhem.

As Gavin put it, “If I did nothing more than pour infantry and British armor into the battle at our end of the bridge, we could be fighting there for days and Urquhart [commander of the British paratroopers at Arnhem] would be lost.” He therefore came up with a daring, but extremely risky, plan to attack both ends of the bridge at once.

“I Have Never Seen a More Gallant Action”

Only 1,341 out of 2,310 troops and 40 percent of the artillery pieces destined for the 101st got through on the 19th, and many of the re-supply bundles landed among the Germans in the Best sector. Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s problem of defending his 25 km sector of the highway was now compounded by shortages of ammunition, fuel, and even food.

The fighting at Best reached a crisis on this day. The 59th Division was now posing a real threat, and early in the afternoon Maj. Gen. Taylor decided he had to throw in more troops to eliminate it. Supported by two battalions of Colonel Joseph Harper’s recently arrived 327th Glider Infantry Regiment and a squadron of British tanks, he committed the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 502nd Regiment. By evening the Germans had broken and fled; more than 300 were killed and over 1,400 captured. As the fighting at Best ended, another German attack developed—this time at Son, where General Taylor had his headquarters. The new German thrust, by Panzer Brigade 107, was aimed at seizing Son and cutting off the advance elements of XXX Corps.

The 107th was a very powerful formation comprising a panzer battalion with 36 Panthers and 11 Jagdpanzer IVs, a full-strength panzergrenadier battalion with 116 SPWs and eight 120mm mortars, and an SPW mounted Pioneer company. Its surprise attack, called a “reconnaissance in force” by the Germans due to the difficult nature of the ground around Son, began shortly after 1715 hours. It was very nearly successful in that a few Panthers were able to take the newly constructed Bailey bridge over the canal under fire, but the situation was saved by the arrival of some of the glider infantrymen and a single 57mm antitank gun. The latter, together with bazooka fire, accounted for two Panthers, and as darkness fell the Germans withdrew.

General Gavin described September 20, 1944, as “a day unprecedented in the division’s combat history. Each of the three regiments fought a critical battle in its own area and won over heavy odds.” To the southeast of Nijmegen, the 505th (less a battalion) and the 508th fought a desperate battle to hold off German forces attacking from the direction of the Reichswald, and in the city itself the third regiment played a decisive part in the capture of the bridges over the Waal. General Browning witnessed this latter event, together with General Horrocks of XXX Corps, and is said to have exclaimed, “I have never seen a more gallant action.”

The German attacks from the direction of the Reichswald were launched by three KGs at around 0800 hours. By early evening they had made considerable progress against the badly overstretched Americans. They captured the villages of Wyler, Beek, and Mook and at one stage threatened the only bridge available to XXX Corps over the Maas-Waal Canal. The

82nd had by this time suffered 150 killed and 600 wounded. Casualties in the Mook battle alone were 20 killed, 54 wounded, and seven missing. This critical situation was eventually restored that night and the following morning by strong American counterattacks, those at Mook and Beek being supported by elements of the attached British armored group.

Assault Across the Waal

Despite its obvious dangers, both Horrocks and the commander of the Guards Armored Division readily gave their approval to Gavin’s plan for the capture of the Nijmegen bridges. It involved joint American/British attacks to secure the southern ends of the rail and road bridges and most of the 504th Parachute Regiment crossing the river in assault boats to the west of the railway bridge with the aim of securing the northern bank. In the case of the road bridge, British tanks were to make a dash across it in conjunction with the American attack. The dangers of the Germans blowing the bridge at this point were obvious.

It took five hours, until 1330 hours, to clear the jumping-off area for the final assault on the southern ends of the bridges and the bank of the Waal from which the river crossing was to be made. Further delays were then experienced in bringing forward 32 British assault boats from the XXX Corps column. A major cause of this delay was another extremely heavy Luftwaffe raid on Eindhoven the previous night, which had blocked roads and caused numerous civilian casualties.

Just before 1500 hours, following an air strike by eight British Typhoons and a 15-minute artillery barrage, the boats, each with 13 paratroopers and manned by men of C Company of the 307th Airborne Engineeer Battalion, set off across the 400-meter-wide river. Major Julian Cook’s 3rd Battalion of the 504th led the way, with Lt. Col. William Harrison’s 1st Battalion following, in a total of six waves. Major Edward Willems’s 2nd Battalion and 30 British tanks provided direct fire support from the south bank near the power station, and some one hundred American guns and mortars provided indirect fire support. Smoke rounds were included in the fire plan to provide some cover for the boats, but much of it blew away before it could be effective.

The story of the incredibly gallant Waal River crossing and the seizure of the north bank by the men of the 504th has been told many times and portrayed vividly in the film A Bridge Too Far.

Meanwhile, the complementary assault against KG Euling at the southern end of the road bridge was reaching its climax. By early evening, despite a considerable number of casualties and the loss of a Sherman, the attack by Lt. Col. Ben Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion and Lt. Col.

Edward Goulburn’s 1st Grenadier Guards, both supported by British Shermans, finally overwhelmed the German defenders. As the Grenadier Guards’ History put it: “All serious German resistance seemed to crack … a patrol from No. 4 Company [Grenadier Guards] moved down to the bridge and, apart from a considerable number of shell-shocked Germans, found it clear…. It remained for the 2nd Battalion [the Grenadier Guards Tank Battalion] to move over the bridge. At 1830, a troop [platoon of four tanks], which had been held in readiness by the round-about, edged forward along the embankment, but it was still too light; they were met by strong anti-tank fire and forced to withdraw.”

Stagnation of the Guards Armored Division

By this time the valiant men of the 504th, despite suffering 134 casualties killed, wounded, or missing, had secured the north end of the railway bridge and were continuing their advance to the north and east. At 1900 hours, as they approached the north end of the massive road bridge, the troop of four Grenadier Guards’ Shermans was ordered to advance again.

Despite the fading light, they came under fire from two 88mm guns on the far side, a Sturmgeschütze firing straight down the bridge, and from men with hand-held antitank weapons and machine guns on the structure itself. The two rear tanks were hit but, against all expectations, the other two succeeded in crossing and after knocking out the Sturmgeschütze, linked up with Lt. Cmdr.

Reuben Tucker’s paratroopers about a kilometer up the road. The time was 1915 hours. Within an hour the Americans had eliminated the antitank threat, and British engineers, more Shermans, four 17-pounder antitank guns, and two companies of infantry had reinforced the slender bridgehead.

With the remnants of the beleaguered 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem, less than 18 km away to the north, the Americans naturally expected the British armor to move rapidly to their rescue—but nothing happened. Lt. Cmdr. Tucker was, understandably, furious. He is said to have told a Guards major, “Your boys are hurting up there at Arnhem. You’d better go.”

There is even a report that one American company commander was so angry about the failure to advance that he actually threatened a British officer with his submachine gun, causing him to close the hatches on his Sherman. Certainly, Tucker said to General Gavin the next morning, “What in the hell are they doing? We’ve been in this position for over 12 hours and all they seem to be doing is brewing tea.” In view of the casualties his regiment had suffered securing the north bank of the Waal, his anger would seem to be justified.

A British Guards officer later wrote: “Patrols of Americans, wearing rubber-soled boots that made no sound, kept passing through us, alert and eager to engage the enemy. For our part, we just sat in our positions all night…. The situation in Arnhem remained desperate. Yet the Guards Armoured Division did nothing.”

Sadly, it was true. It would be 18 hours before the advance was resumed, and yet for five hours, from 1900 until midnight, there was virtually nothing to stop an advance up the Elst-Arnhem road. Once again, however, British caution ruled the day. The plight of those in the Arnhem area seems to have taken second place to worries about the XXX Corps corridor south of Nijmegen. Or was it perhaps lethargy, military incompetence, or an unwillingness to accept a few casualties for the good of the majority—not least the Dutch people north of the Waal?

Many excuses have been offered for the failure of the Guards Armored Division to advance on the evening of September 20, but none of them is totally satisfactory. One junior Irish Guards officer later wrote: “I led my platoon over the [Waal] bridge in the dark to take up a position astride the road ahead. Again, we sat there all night, with no German counter-attack…. It was a moment when you would have expected the commanders to order the Grenadiers [in Shermans] to continue hell for leather to Arnhem, with the 3rd Battalion Irish Guards riding on the tanks. Neither battalion was otherwise seriously engaged all night.” The failure of Horrocks to order the advance to continue “hell for leather” that evening, or of Adair to seize the initiative and give the necessary orders, was to result in tragic events on both sides of the lower Rhine.

Not surprisingly, the situation in front of the Nijmegen bridgehead on the night of September 20 soon began to change and, shortly after midnight, a new German defensive line, some 4 km north of the bridge, began to build. It was manned initially by KG Reinhold, and by dawn the following day it had been reinforced by 16 Mk IVs and Sturmgeschütze and a panzergrenadier battalion of the Frundsberg, newly arrived from the Pannerden crossing.

In an episode almost as amazing as the American crossing of the Waal, SS Captain Karl-Heinz Euling led the 60 or so survivors of his KG to safety that night. They fought on until around 2225 hours in various locations near the bridge and then managed to slip away, quite literally under the noses of the British, to find rowing boats and join their Frundsberg comrades on the north side of the river. Euling was later awarded the Knight’s Cross for his actions on this day.

The Defense of Hell’s Highway

General Taylor’s greatest concern was another attack by German armor, and his worst fears were realized when Panzer Brigade 107 attacked Son again early on the 20th. Panthers soon controlled the bridge by fire, and it would almost certainly have fallen had not 10 British tanks “belatedly responded to an SOS dating from the crisis of the night before.” The Germans found they were unable to close on the village due to the canal, and after losing four Panthers to the British tanks they withdrew. Nevertheless, it had been a close-run thing.

General Taylor had already decided that since he could not maintain a static defense along the whole length of Hell’s Highway, he would try to surprise and unbalance the enemy by limited offensive thrusts of his own. Accordingly, in the first of these operations Lt. Col. Kinnards’s battalion of the 501st swept northwest from Veghel along the Willems Canal and “accounted for about 500 Germans, including 418 prisoners.”

Between 0830 and 1130 hours on September 21, two brigades of the long-awaited British 43rd Division, part of XXX Corps, arrived in Nijmegen. In view of the situation in the Arnhem sector, one would have expected them to continue to the north side of the Waal, but instead both remained in the city. This was, however, clearly a blessing in disguise for Gavin’s division. With the British assuming responsibility for the city, the 82nd could focus its attention on its vulnerable eastern flank.

Farther south, General Taylor’s tactic of carrying the attack to the enemy saw two battalions of Lt. Col. Johnson’s 501st Regiment and two battalions of Lt. Cmdr. Michaelis’s 502nd attempt to envelop the Germans in the Schijndel area between Veghel and St. Oedenrode. The operation began after dark and was progressing well, but as shall be seen, it had to be called off at 1430 hours the following day due to another all-out German effort to cut Hell’s Highway.

The 101st, with help from British tanks, had so far successfully defended Hell’s Highway, but its task was being prolonged by the slow progress of the British on either flank. By the morning of the 22nd, when a major German attack was launched in the Veghel area, their VIII Corps was still southeast of Eindhoven and their XII Corps around Best, 8 km west of Son. The Americans were so stretched that in places the “front” was quite literally the edges of the main Eindhoven-Nijmegen road and defended only by the XXX Corps troops moving along it.

The failure of the flanking British corps to keep pace with XXX Corps and thus relieve the pressure on the Americans has been the subject of much postwar discussion. The bare facts are that XII Corps was not ready to advance on September 17, and three days later had covered only 15 km to reach the Turnhout-Eindhoven road, while VIII Corps, which did not begin its advance until the 20th, took six days to reach the Maas River, 25 km southeast of Nijmegen. Although no one would question the bravery of the junior officers and soldiers or the severity of the fighting, one has to question the motivation of some of their superiors and compare it with that of their opponents. It is significant that, long after the war, General O’Connor, the commander of VIII Corps, admitted that he had been instructed not to press too hard on his flank!

The German attack in the Veghel area was launched at 0900 hours on the 22nd from both sides of Hell’s Highway. A KG Huber, with three infantry battalions, an artillery battalion, a flak battery, seven antitank guns, and four Jagdpanthers, attacked from the west. Following up was a parachute regiment, but it would not reach the battle area until the following day. The heaviest assault came from the east and was mounted by a KG Walther. This KG included the Panzer Brigade 107, a Frundsberg panzergrenadier battalion, an artillery battalion, and a flak battery, and KG Heinke. Panzer Brigade 107 had already been in action two days previously at Son, losing 10 percent of its armor in the process.

The 101st Airborne Division was inevitably too thinly spread to resist a strong attack at a single point. Lt. Col. Robert Ballard’s 2nd Battalion of the 501st was positioned in Veghel, but the two other parachute battalions of the regiment were already involved in the Schijndel area. Fortunately, members of the Dutch Resistance had warned General Taylor of the German buildup on both sides of the corridor, and this enabled him to deploy some of his slender reserves: Lt. Col. Ray Allen’s battalion of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, 150 men of Colonel Sink’s 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and a battalion of British tanks.

The German attacks were violent and, although not fully coordinated, succeeded in cutting the road between Uden and Veghel by 1330 hours. Panthers then turned south toward Veghel, and shortly afterward KG Huber, advancing from the west, was able to bring fire to bear on the vital bridge over the Willems Canal. The Americans, however, were able to pull back the two battalions of the 501st from the Schijndel area to support their comrades in Veghel, and these battalions were able to engage and virtually annihilate KG Huber from the rear.

Meanwhile, the arrival of a small reserve force heading for Uden, supported by a squadron of British tanks and a battalion of glider infantrymen from the main divisional LZ, halted the move of the German tanks from the north and stabilized the situation. According to the U.S. Official History, the Americans “requested air support, but unfavorable weather denied any substantial assistance from that quarter.” This statement is contradicted by General Brereton, who claimed that 119 Typhoon sorties were flown in support of the ground troops on this day. RAF records show a total of 74 Typhoon sorties being flown: 66 in the 101st Airborne sector where the alleged target was up to “100 tanks” and eight in the Reichswald area.

By last light, the 101st was holding the Veghel area with eight battalions of parachute and glider infantry and two companies of British tanks, but this force was still not considered strong enough to guarantee Hell’s Highway for the movement of the XXX Corps units and supplies urgently needed north of Nijmegen. Knowing that the Germans would intensify their attacks during the night and the next day, Horrocks gave orders that a tank battalion and an infantry battalion from the Guards Armored Division in Nijmegen were to be sent back down the corridor to help the Americans. They received the order to move at 1230 hours and, after brushing with German elements south of Uden, went firm into the village as darkness fell.

In the meantime, the commander of the British Second Army, General Miles Dempsey, in an indication of how seriously he viewed the situation, placed the 101st Airborne Division under the British VIII Corps and told the VIII Corps commander to move one of his divisions to Veghel.

Keeping the Highway Open

By last light on September 23, the 82nd had expanded its Nijmegen defensive perimeter to an average depth of 7 km in the east and 12 km in the southeast. Although the Germans had been reinforced, the American paratroopers had fought them to a standstill, and the expanded American bridgehead between the Maas and the Waal provided a much-needed firm base for the further advance of the British VIII Corps. It also provided greater protection for the vital Nijmegen bridges. With the safe, if belated, arrival of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment on this day, Gavin could be justly proud of his division’s achievements. His own performance had been remarkable. He had been in constant pain from a suspected broken back following his parachute landing on the 17th.

Farther south, in the 101st Division’s sector, the situation was less stable. The balance of the Frundsberg’s KG Heinke—SS panzergrenadiers and some panzerjägers—had closed up to KG Walther, as had a battalion of paratroopers. Thus reinforced, Walther resumed his attack on the Veghel sector of Hell’s Highway. In conjunction with this attack from the east, the 6th German Parachute Regiment, commanded by the famous Baron von der Heydte, already exhausted after a 48-hour approach march, was ordered to attack from the west—on basically the same axis as that taken by the ill-fated KG Huber the previous day. Neither attack was successful.

By midday the paratroopers from the west had been halted by their American counterparts and, at about the same time, Walther, no longer able to ignore the steady advance of the British VIII Corps to his left rear, decided to pull back. An hour later the overall American commander in Veghel, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, sent two battalions, with British tank support, north to clear the road, and by 1520 hours his men had linked up with the British Guards units moving south from Uden. After 24 hours, Hell’s Highway was open again. German reports confirm that Panzer Brigade 107 lost 16 Panthers, 24 SPWs, and over 300 men in its struggle to cut the highway.

A further Allied success on this day was the safe delivery by glider of the remaining artillery and 3,000 men of the 101st Airborne Division.

Von der Heydte’s 6th German Parachute Regiment, with four weak battalions and a few assault guns, attacked Veghel again at 1000 hours. Heavy fighting between the rival paratroopers followed, and while this was going on a KG Jungwirth, cobbled together from another infantry division, found an undefended section of the highway, 6 km southwest of Veghel. Within 24 hours of Hell’s Highway being reopened, it was cut again. Despite heavy interdiction from American and British guns, German paratroopers successfully reinforced KG Jungwirth during the night, and it soon became clear that much stronger Allied forces would be needed to reopen the vital road to Nijmegen.

At 0830 hours on Monday morning, a combined attack by American and British forces was launched to clear the Germans off Hell’s Highway. The men of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment advanced from the direction of Veghel, while a reinforced battalion of the 502nd together with British infantry moved up from St. Oedenrode. British tanks supported both groups. Although they were surrounded on three sides, the Germans held on and sensibly used their time to heavily mine the whole area.

Although the Germans eventually withdrew after dark that evening, it took Allied engineers until 1400 hours the following day to clear the mines and finally declare Hell’s Highway safe for use. From now on, the Germans would have to resort to artillery fire and aircraft to interdict the constant flow of traffic. In this respect, a major attack by 40 German aircraft took place against the Nijmegen road bridge on the 25th. One bomb hit, but the bridge remained passable.

“My Country Can Never Again Afford the Luxury of a Montgomery Success”

The withdrawal of the British and Polish survivors from the Arnhem sector took place between 2140 hours on the 25th and 0530 hours on September 26 in heavy rain. Nearly 2,300 men reached safety, including 160 Poles.

Operation Market-Garden was over. It had cost the Allies over 16,000 soldiers and 248 airmen. Of nearly 12,000 British and Poles committed in the Arnhem area, 1,446 British, including 229 glider pilots, and 97 Poles were killed, and 6,414 British and 111 Poles, many of whom were wounded, became prisoners. The British XXX Corps suffered 1,480 casualties, and VIII and XII Corps lost 3,874 men between them.

A total of 29,628 American troops were delivered into Holland by parachute or glider during Operation Market-Garden. The 82nd Airborne Division lost 215 killed, 790 wounded, and 427 missing; the 101st suffered 315 killed, 1,248 wounded, and 547 missing; and 122 glider pilots were lost, of whom 12 were killed. Precise details of German casualties do not exist, but they probably totaled about 6,400.

With the war still in progress, it was inevitable that Market-Garden would be presented to the British and American people as a victory. Churchill described it as “a decided victory,” and Montgomery claimed it was 90 percent successful since 90 percent of the ground specified in the operation order had been taken. To this latter claim, Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands is said to have replied, “My country can never again afford the luxury of a Montgomery success.”

In reality, Market-Garden was a strategic failure. The West Wall had not been outflanked, the British Second Army was not positioned for an attack on the north flank of the Ruhr, the German Fifteenth Army had not been cut off, and there had been no collapse of German arms. The salient achieved led nowhere and was to prove extremely costly in the coming months.

The vast majority of those involved in Market-Garden, of whatever nationality, displayed great bravery and earned the respect of their adversaries. In the case of two of the major participants, the Americans and Germans, their senior ground commanders—Gavin, Taylor, Model, Bittrich, Harmel (Frundsberg), and Harzer (Hohenstaufen)—demonstrated outstanding military competence. The same cannot be said of the British. The seven most directly involved—Montgomery, Dempsey, Browning, Horrocks, Adair, Urquhart (commander, 1st Parachute Division), and Thomas (commander, 43rd Infantry Division)—must bear responsibility for the failure of the operation.

The aftermath for those who returned from Market-Garden differed markedly, depending on their nationality. The British survivors of the Arnhem operation were flown back to England on September 30 and welcomed as heroes. In a surprisingly generous move by Eisenhower and the American authorities, the two U.S. Airborne Divisions were left under Montgomery’s command and stayed in the line in Holland for a further six weeks. They suffered another 3,594 casualties, including 685 killed. Today, few Brits are aware of the contribution and sacrifice made by the Americans in Market-Garden. Horrocks, however, was in no doubt when he wrote after the war: “As this difficult battle progressed I became more and more impressed with the fighting qualities of the 82nd and 101st U.S. Airborne Divisions…. What impressed me so much about them was their quickness into action…. They were commanded by two outstanding men…. Both were as unlike the popular cartoon conception of the loud-voiced, boastful, cigar-chewing American as it would be possible to imagine. They were quiet, sensitive-looking men of great charm, with an almost British passion for understatement…. Under their deceptively gentle exterior both Maxwell Taylor and Gavin were very tough characters indeed. They had to be, because the men they commanded were some of the toughest troops I have ever come across in my life.”

The Poles, after marching back to Nijmegen under occasional mortar fire, spent the next 10 days on guard and patrol duties there before being returned to England. Their commander, Maj. Gen. Stanislas Sosabowski, was sacked on December 9, undoubtedly at Montgomery and Browning’s insistence. Not surprisingly, two of his battalions went on what turned out to be an unsuccessful hunger strike.

For the Dutch people, the aftermath of the fighting was to be the most bitter and painful of all. Some 100,000 people had been forced out of the Arnhem area. Their homes had been destroyed and systematically looted by the Germans, who then cut their rations to less than 500 calories a day in what became known as the “Hunger Winter.”

In retaliation for their assistance to the Allies during Market-Garden and a countrywide railway strike begun by Dutch workers on September 17, the Germans stopped all inland shipping. Without trains or barges it was impossible to move sufficient food from the agricultural east to the towns and cities of the west. It has been estimated that some 25,000 Dutch people died of starvation that winter. As they died, they wondered why the Allies did not continue their advance to free them.

The answer was simple. The Germans were too strong and the ground too difficult. Any major advance would almost certainly have led to a level of destruction that would have resulted in the flooding of most of the Netherlands. The Allies turned instead toward the Rhine.

“Gavin, Taylor, Model, Bittrich, Harmel (Frundsberg), and Harzer (Hohenstaufen)—demonstrated outstanding military competence. The same cannot be said of the British. The seven most directly involved—Montgomery, Dempsey, Browning, Horrocks, Adair, Urquhart (commander, 1st Parachute Division), and Thomas (commander, 43rd Infantry Division)—must bear responsibility for the failure of the operation.”

A rather partisan perspective derived from one source, which seems to be the film, with little accompanying analysis.

Gavin and Taylor both failed to secure their most important objectives on Day 1, that failure and that failure alone is why 1st Airborne weren’t relived in time. How can you call that competence?

XXX Corps were only held up at Son and Nijmegen, and were forced to expend great resources to capture and secure both. It was the Grenadier Guard that took Nijmegen town and the road bridge. Other than the 24hr delay at Son and 48hour delay at Nijmegen they kept to their timetable: from Joe’s Bridge – Son; Son – Nijmegen; Nijmegen – Elst. Had those bridge been open when XXX Corps arrived they could well have been south of Arnhem on Day three, instead of day six. After expending most of their force securing the bridges the US paratroops were supposed to.

In the Film the delay is caused by XXX Corps failure to bring up boats in time. In fact the boats were there straight away, the delay was clearing the riverbank in preparation for the crossing, and the Guard having to fight their way through a Nijmegen town to be in a position to cross in conjunction with the US Paras.

Not only did Gavin fail to secure his Primary Bridge, he allowed German forces two days to reinforce their troops in the town.

You’ve ignored the vital task mission of securing the right flank of the units going in to take Tilburg and Walcheren, which is why Market Garden had to got ahead and was largely successful. The loss of two light infantry brigades at Arnhem may have been an unnecessary addition to the plan, but greater forces had been sacrificed for less before – Hong Kong ’41, Crete ’41, Anzio, Cassino, the list goes on.

You also missed out that it was US General Bereton that insisted on inadequate landing zones for the British – that wasn’t Browning’s or Urqhart’s decision those were US Air Transport Command orders.

You fail to take in any of the recent study that shows the intelligence summary of the state of tanks at Arnhem was correct – 1st Airborne would only meet a handful and destroy most of them before day three. The King Tigers and StuGs came from as far away as Czechoslovakia.

You claim that Sosabowski was cashiered by Browning and Montongery. Hoe then do you explain far more senior Free Polish commanders Anders and Maczek being sacked or sidelined in the same period? Just before Normandy Stalin refused to recognise the Polish Government and forces in Exile in the west – of which Anders, Maczek and Sosabowski were high profile members. He announced that HIS polish army would be the liberators and HIS poles would form the post war government of Poland. At Yalta FDR and Churchill agreed and the Free Polish Army was slowly wound up, used up and sidelined.

That Browning took part in his dismissal isn’t in doubt – but he was the last in a long line of Trans-Atlantic politicians and Generals who had no further use for the Free Polish Army. The saddest betrayal of WW2.

The highly partisan writings of Cornelius Ryan (Longest Day and Bridge too Far) were written with the patronage of President Eisenhower and Chief of Staff Ridgeway (Browning’s opposite number in Holland. Their conclusions should be compared with more modern, better researched and less political works.

I would agree that the article was a bit harsh though some points mentioned were noted in after action reports. That said you were equally quick to condemn American forces with the same bias you attached to this author.

In my view it was what it was presented at the outset…a gamble. Unfortunately it failed. For myself I’m reminded of General George Picketts responses for the Confederate loss at Gettysburg when blame was goal of the day, “ I always thought the Yankees had something to do with it.” The same can be said of the Germans.

Eisenhower made one mistake. He listen to Montgomery . He should never went in to Market Garden. We had the best . Patton would have had every one home by Christmas.

What a biased summary, full of unsubstantiated quotes.

I’ve no doubt all troops including 82nd and 101st US Paratroop divisions performed well, though they did far less fighting in this operation than the much-criticised British – the mortality and casualty rates prove this. No mention of the strong opposition the British faced initially, 9 tanks were taken out in quick succession. They were on time at Nijmegen (less than 48 hours from commencement), and were amazed that 82nd Division had not seriously attempted to take its key priority – the Nijmegen Bridge. Whether this was chiefly Browning or Gavin’s decision to deprioritise it is debatable – probably both based on what they say. But they were informed by their own intelligence groups at 6pm on 17th that there were no serious formations of Germans in the Reichswald, and by Dutch Underground. yet only 200 from 5.352 troops landed on the 17th made a weak attempt to take it. That was chiefly left to the Grenadier Guards and 505th PIR who managed to smash through the strong German bridge defences on the 20th. The 504th took the rail bridge in a brave coup de main attack, but after fighting for two full days in Nijmegen, to take the bridges, the situation on the evening of the 20th was very different. Everyone was expecting a German counterattack. By this point 30 Corps Division reserve the Coldstream Guards were helping the Americans retake Mook, and 43rd Infantry were helping the Americans back down the line. They were also awaiting a resupply of fuel and tank shells that had been expended supporting 504th PIR cross the river. 30 Corps were split all over the sector. I can produce many Grenadier quotes to support this. 45 tanks had crossed by 11am on 21st but several were very quickly taken out. Bottom line is that if Gavin and Browning had not changed the plans, they could have taken Nijmegen Bridge and 30 Corps could have been straight across by 12 noon on the 19th when they arrived, and just 9 miles from Arnhem. Critically, at that point, the number of Germans between Arnhem and Nijmegen was relatively small. After the war, Captain Westover led an official US Enquiry into the failure to take Nijmegen Bridge and found the account of Gavin to be lies. Gavin actually praised Browning at the time, and only started criticising others to save his own skin after the war. I think criticism of Adair, Dempsey and Horrocks is unfair. Urquhart didn’t cover himself in glory at Arnhem, but at least one and a bit of the 3 battalions went for the key priority and effectively held one end of it to prevent the Germans using it for 4 days, exactly what Gavin should have done in Nijmegen, though I accept he was highly tasked.

The German ability to reorganise was first class, in effect the operation was perhaps a week too late by the time it commenced, to be effective.

Perhaps the operation was doomed to failure, but many feel that it was very close to being a success, and only teh failure to tak eNijmegen Bridge

The British 1st Airborne had 1 major objective, that was to capture the bridge at Arnhem and hold it until XXX Corps arrived. They only got 1 battalion to Arnhem and they never actually captured the bridge, just controlled access to the north end of it for a few days. The American 82nd Airborne had to capture the major bridge at Grave, at least 1 bridge across the Maas-Waal Canal, the major bridge at Nijmegen, and defend the heights at Groesbeek against an expected German counterattack from Germany itself, and hold a long stretch of highway open for use by XXX Corps, all considered mission critical objectives, and had to make do with their Glider Infantry regiment still in England until day 7. I think it was unrealistic to think they could accomplish all that with the force available. Having said that, I do think at least a couple of battalions should have gone for the bridge at Nijmegen right away, but it was quickly defended by SS troopers and other garrison forces and would have been a tough nut to crack in any case. The 101st had multiple such objectives as well and the Son bridge would probably have been blown no matter what. They had least secured both sides of the canal so the British engineers could build the Bailey more quickly. They also tried to capture an alternate route bridge not part of the original plan.

Overall, I believe the operation was a stretch for all the Airborne forces engaged. The Germans showed amazing resilience and ability to cobble together scratch forces when needed and that may have been the biggest factor of all in the defeat of the operation.

Was flawed planning the primary reason Operation Market Garden failed?

“The vast majority of those involved in Market-Garden, of whatever nationality, displayed great bravery and earned the respect of their adversaries. In the case of two of the major participants, the Americans and Germans, their senior ground commanders—Gavin, Taylor, Model, Bittrich, Harmel (Frundsberg), and Harzer (Hohenstaufen)—demonstrated outstanding military competence. The same cannot be said of the British. The seven most directly involved—Montgomery, Dempsey, Browning, Horrocks, Adair, Urquhart (commander, 1st Parachute Division), and Thomas (commander, 43rd Infantry Division)—must bear responsibility for the failure of the operation.”

This appears ever so slightly biased.

I am afraid this article is quite typical of the general anti-British tripe that permeates through American revisionist history. You only have to watch the US WW2 Institute presentations to get a feel for this.

BTW, Despite what the film shows, the 82nd did NOT take Nijmegen Bridge, the Grenadier Guards did that. Even the official post-battle 82nd Division reports confirm that.

Thankfully, people in Britain are beginning to see the warped criticism of 30 Corps here, and are realising what really happened. Its a great shame, because the British and Americans fought superbly alongside each other during the operation and wider Western European theatre. But I implore any open-minded reader, please take such amateurish articles as this with a pinch of salt.

You may be interested to learn that the author of this article, Michael Reynolds, was a British Army Major General. General Reynolds saw combat in Korea as a platoon commander where he was severely wounded, served in Cyprus and Northern Ireland, and much later commanded NATO’s Allied Command Europe Mobile Force (Land).