By Peter Kross

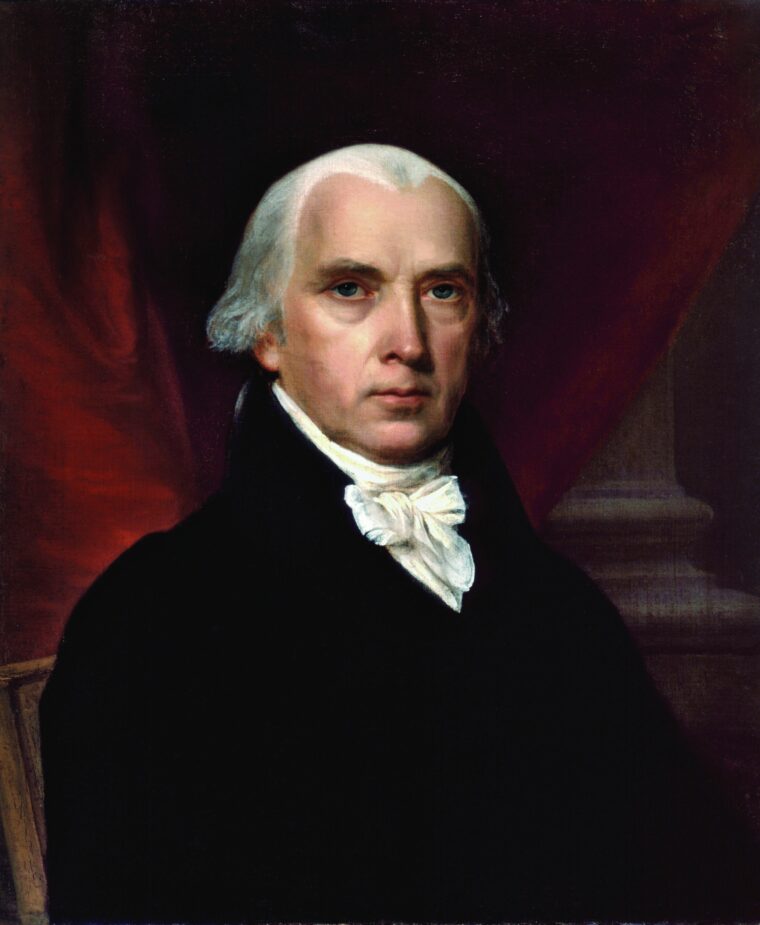

Almost a decade after winning the Revolutionary War against Great Britain, the youthful United States was determined to expand its territorial boundaries and become a truly continental nation. President Thomas Jefferson made the first move by purchasing the vast Louisiana Territory from France, giving the United States expanded commercial interests along the vital Mississippi River. Jefferson’s successor, James Madison, continued the expansionist efforts, setting his sights on gaining control of East Florida, then administrated by Spain.

Florida was teeming with Americans, as well as a large number of African American slaves who had made their way south seeking their freedom. Madison’s goal was to check Spanish territorial expansion and add Florida to the American union. To that effect, he put in motion a large-scale covert operation much like those undertaken by the Central Intelligence Agency 200 years later. The operation involved U.S. military support for the indigenous rebels who had “invited” the Americans to come to their rescue. The person who was to serve as the point man in this covert mission was George Matthews, a former Revolutionary War veteran, governor of Georgia, and member of Congress.

George Matthews and William Claiborne

Matthews, born into a wealthy Virginia family, served in the Virginia Militia during the Revolutionary War, seeing action in both Georgia and South Carolina, and was captured by British forces in December 1781. After the war ended, Matthews turned to politics and served as governor of Georgia in 1787-1788. He later served in the House of Representatives before returning to private life. During his own political career, Madison had followed Matthews’s rise to prominence. When it came time to send an emissary to East Florida to scout the political landscape, he chose the 71-year-old Matthews as his emissary.

Madison got his first inkling that something was about to change in East Florida when he received a letter from Samuel Fulton on April 20, 1810. Fulton was adjutant general of West Florida, ostensibly on the payroll of the Spanish. He wrote to Madison suggesting that East Florida was ripe for insurrection and that the United States should not stand idly by and let the Spanish control the territory. Fulton worked for Vincente Floch, governor of West Florida, who was the man to see in the neighborhood. Fulton offered his services to the president in whatever capacity he chose.

Another participant in the early talks was William Claiborne, a former governor of Mississippi who was now in that same position in New Orleans. Floch went to meet with Claiborne in New Orleans in April 1809 and they discussed the Florida situation. Floch told Claiborne that the Spanish-American colonies would continue to be part of Spain as long as the French were kept out of the area. If this did not happen, then Florida was ripe for either U.S. or British intervention. Claiborne relayed this information to Madison, who immediately set into motion Matthews’s covert mission to East Florida.

Constructing a “Patriotic Movement” in Florida

Claiborne met with Madison in Washington to begin strategic planning. It was decided that an overt U.S. invasion of Florida was out of the question and that a more indirect policy was needed. It was decided that a spontaneous “Patriotic movement” was to spring up in Florida, with residents declaring their independence from Spain. The Florida Patriots would then ask for official U.S. help and the Madison administration would have no choice but to act in their defense.

Madison chose William Wykoff, a member of the Executive Council of New Orleans, to get the ball rolling. He met with various leaders among the Patriot groups and passed on their demands for U.S. assistance. With Wyckoff’s news in hand, Madison sent Matthews as his personal agent to go to East Florida to assess the political and military situation on the ground.

At 71, Matthews was not the most physically fit man in the world to take on such an arduous task, but in the summer of 1810 he departed for Mobile and Pensacola to begin preliminary talks with his Spanish contacts. To relay his messages to Washington, Matthews used the services of Senator William Crawford of Georgia. Matthews met with Floch in Mobile and reiterated Madison’s offer to support any Spanish rebellion against French rule. Matthews offered to pay for ammunition and other essentials for Floch if that would cement a deal.

Madison sent Governor David Holmes of Mississippi Territory as yet another one of his emissaries to West Florida. Holmes reported to Madison on a convention in West Florida by “dissidents” that was the beginning of an insurrection against Spain. A group of soldiers of fortune next attacked a Spanish garrison, doing little damage. However, the message was clear—the United States was going after Florida.

The Florida Convention

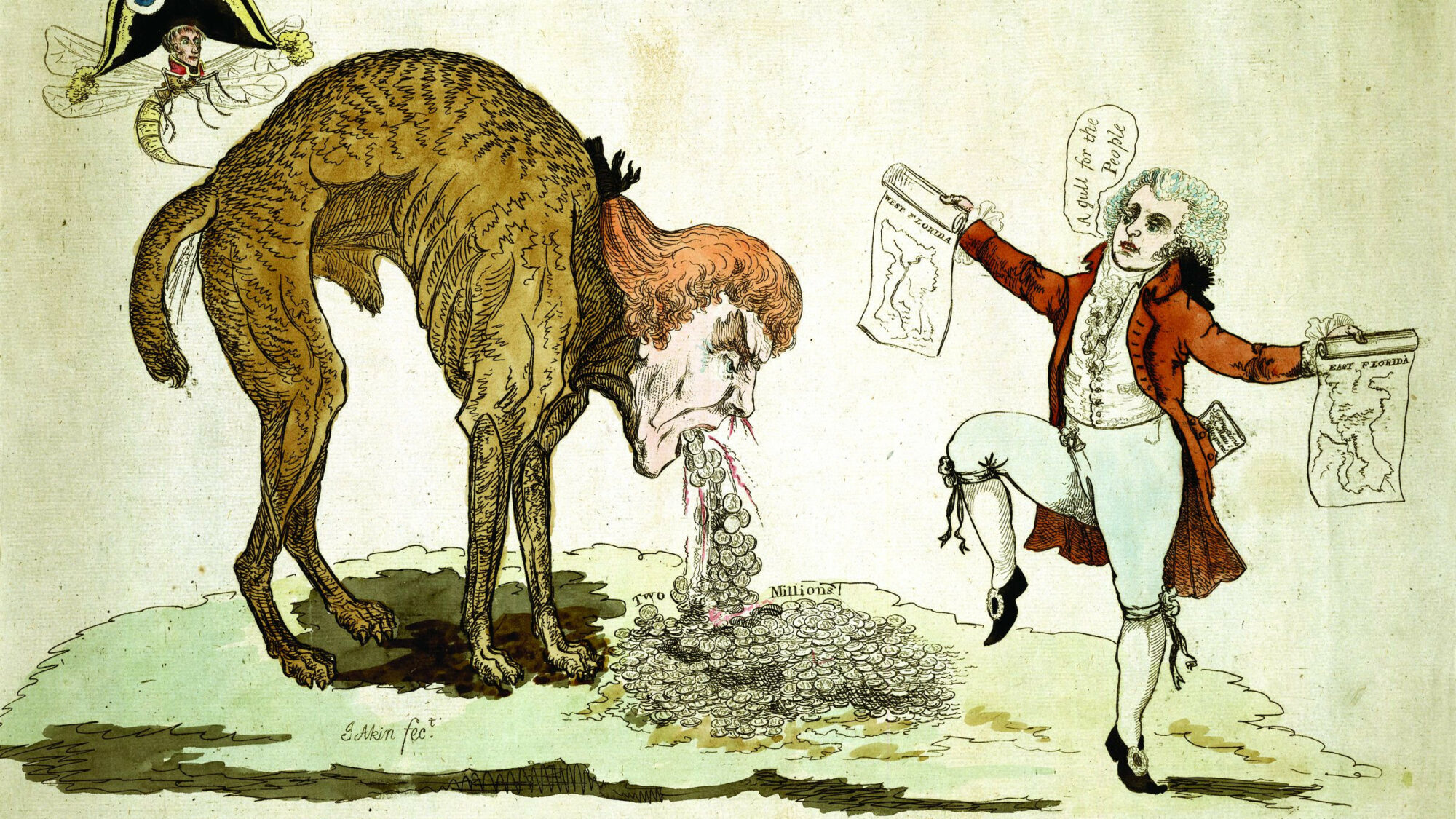

Much to Madison’s liking, the Florida convention called for a declaration of independence for West Florida and asked for help from the United States. On October 10, 1810, Holmes sent the independence message to Washington with his sign of approval. On October 27, 1810, Madison issued a proclamation in Washington giving Claiborne the go-ahead to take possession of West Florida as part of the New Orleans territory. The proclamation read in part: “Now it is known. That I, James Madison, President of the U.S. of America, in pursuance of these weighty and urgent considerations, have deemed it right and requisite that possession should be taken of the said territory in the name and on behalf of the United States.”

French reaction to the president’s annexation announcement was swift. General Louis Turreau, the French ambassador to the United States, called in Secretary of State Robert Smith for urgent talks, but Smith smoothly denied any U.S. participation. Madison’s covert operation to annex East Florida came without the consent or knowledge of Congress. Like many other such missions during the 20th century, the East Florida expedition was on a need-to-know basis, and Congress was not kept in the loop. It wasn’t until many months later that Madison informed Congress about his secret machinations in Florida.

“The Inhabitants of the Province are Ripe for Revolt”

With all the dominoes in place, Madison met with Matthews in Washington in January 1811 to give him his final instructions. Colonel John McKee, who served as an Indian agent, also took part in the East Florida mission. On January 26, 1811, Madison relayed his written instructions to both McKee and Matthews. Exactly what the president wrote to both men is long gone, and it is almost impossible to discern just what their orders were. Secretary of State Smith wrote to Matthews saying that he should “repair to that quarter [Florida] with all possible expedition, concealing from the general observation the trust committed to you, with that discretion with the delicacy and importance of the undertaking require.”

Both Matthews and McKee met with Floch, who rebuffed their interest in acquiring WestFlorida. They now turned their attention to East Florida, the main purpose of their trip. Matthews hired an unknown man to be his agent in Pensacola and act as his eyes and ears on the ground. At one point, Matthews traveled to East Florida to find a suitable place in which to build a fort. Over time, Matthews and McKee had secret operatives traveling to Mobile, New Orleans, and Pensacola to collect intelligence.

It was McKee’s job to follow any rumors of Spanish intrigue in East Florida, and he sent his reports directly to James Monroe, who had just become secretary of state after Madison fired Smith. Matthews sent his correspondence to Monroe as well, and the two developed a good working relationship. On August 3, 1811, Matthews penned a letter to Monroe asking that his mission be drastically changed. He asked that military supplies and money be sent to him directly for the Patriotic forces that were allied with the United States. “The inhabitants of the province are ripe for revolt,” wrote Matthews. “They are however incompetent to effect a thorough revolution without external aid.” It was his opinion that if the rebels were provided with sufficient supplies, it might turn the tide of events in America’s favor.

While Madison was cagey enough not to tell Congress the whole truth about his Florida operation, he gave the members enough information to induce the representatives to provide him with an almost-blank check to take whatever action he deemed necessary. Part of the congressional message said that the president had the right “under certain circumstances, to take possession of the country lying east of the Perdido River and south of the state of Georgia and the Mississippi Territory and for other purposes.” Congress also gave the president authority to use Army and naval forces if he deemed it necessary to carry out the East Florida mission.

A “Patriotic Army”

Matthews came back from Florida and began to assemble his force. He recruited several soldiers of fortune from local cattle ranchers, adventurers who were looking for action and wealth, slave smugglers, and others of dubious distinction. On March 16, 1812, Matthews and his men arrived at the St. Mary’s River, which was the boundary between the United States and East Florida. There they were met by a man named Colonel John McIntosh, who took military control over the so-called Patriotic Army.

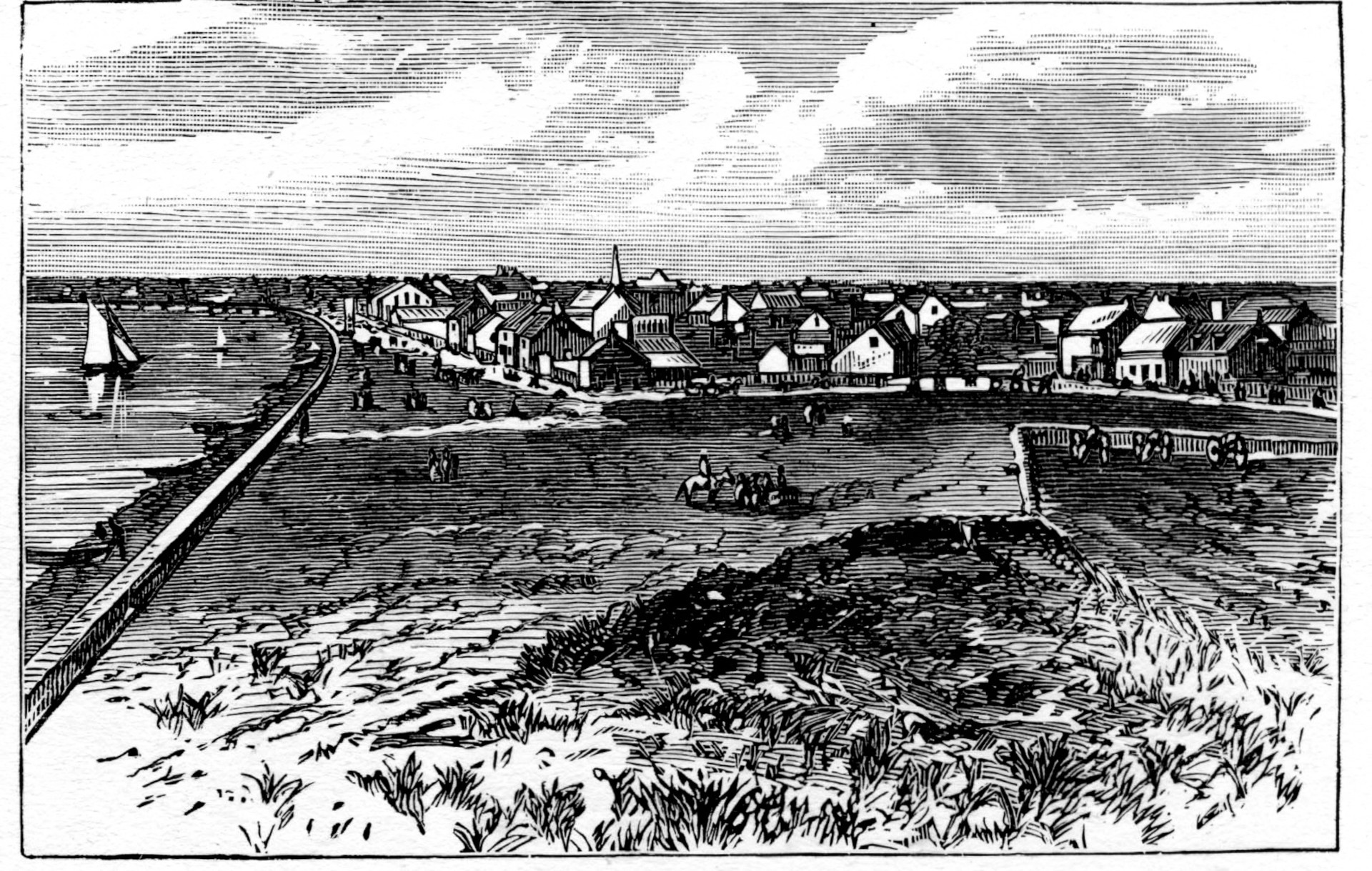

McIntosh and his men attacked the town of Fernandina on Amelia Island. U.S. Navy gunboats stood by to render assistance if necessary. McIntosh demanded the surrender of the town from the Spanish authorities, who gave in without a fight. In due course, a new country called the Republic of East Florida was declared, and Matthews and a detachment of soldiers took control of the area and moved in to protect the city. After the successful takeover of East Florida, Matthews sent an urgent dispatch informing Madison of his success.

Madison seemed, however, to have a sudden change of heart regarding the whole East Florida incident. By April 1812, Matthews’s men had also seized St. Augustine, but for whatever reason, when Monroe heard of the incident, he promptly chastised Matthews for acting in violation of his orders. The original covert nature of Matthews’s mission was drawing too much unwarranted attention in Washington, and the president decided to pull the plug on the entire operation.

Losing All Plausible Deniability

In Washington, Spanish and British diplomats as well as an inquiring Congress were demanding answers about just what Matthews and his company were doing in the swamps of East Florida. Plausible deniability was now out of the question, and the East Florida operation was too hot to handle politically. The Madison administration backed quickly if quietly out of the picture.

Infuriated by the deceptive nature of the administration in Washington, Matthews decided to return to Washington and plead his case. He was officially relieved of his duties on April 4, 1812, and made plans to return home. While Matthews was en route to Washington, he suddenly died on the trail. No one knows just how or why Matthews died, but his death conveniently eliminated the one person who could tell the entire story of his secret machinations in East Florida and the roles given to him by Madison and Monroe. It is doubtful that his passing was mourned in the White House.

Madison quickly replaced Matthews with another emissary to East Florida, the governor of Georgia, David Mitchell, who was given more leeway than Matthews. An American military presence in the area was maintained. In 1819, Florida was incorporated into the United States under terms of the Adams-Onis Treaty, by which Spain agreed to sell its Florida possessions to the United States in return for $5 million in damages done during the recent invasion by General Andrew Jackson. By then, George Matthews and his earlier invasion were long since forgotten.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments