By Michael E. Haskew

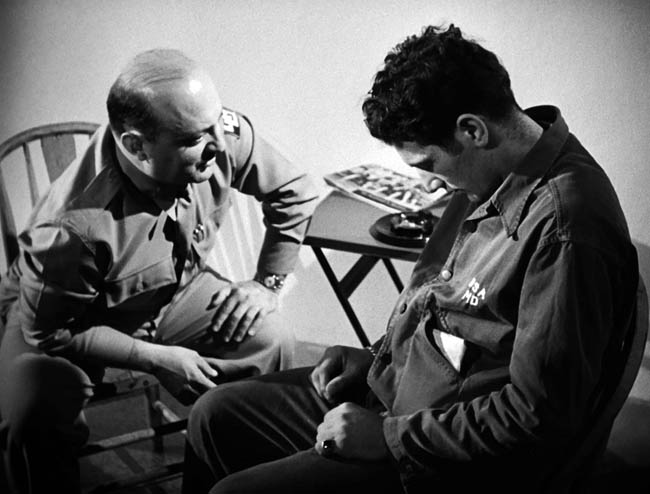

The monotonous rattle and snap of the film projector provided a steady accompaniment to the images flickering across the screen in the darkened room. Images of suffering, destruction, and death flashed in stark black and white before the eyes of the audience—difficult for even a hardened combat veteran to watch.

But this audience was a group of stateside staff officers invited to a screening of director John Huston’s film The Battle of San Pietro. The first film of its kind, purported to depict American soldiers in combat against the Germans at the Italian mountain town of San Pietro Infine, it portrayed with harsh realism the struggle of one of World War II’s most difficult campaigns, laying bare the cost of the fighting on the road to Rome and perhaps raising as many questions as answers concerning the butcher’s bill in Italy during World War II and in this otherwise typical battle against the Germans.

Huston, already a celebrity who had begun his Hollywood career as a screenwriter in 1938 and won acclaim in his directorial debut with The Maltese Falcon in 1941, had joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps in 1942 with the rank of lieutenant. His career in motion pictures spanned nearly 50 years and included two Academy Awards along with 15 nominations. His films include such classics as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Asphalt Jungle, The African Queen, The Misfits, Fat City, The Man Who Would Be King, and The Red Badge of Courage.

Before his discharge from the Army with the rank of major, Huston made three documentary films for the Signal Corps, and The Battle of San Pietro was by far the most famous, though all three were quite controversial. Historians have concluded that the purpose behind the film was possibly threefold: to give recruits and soldiers going through basic training some idea of what modern combat was like, to provide some context and understanding of just what obstacles the Italian Campaign presented and explain its slow progress, and to possibly reassure the American public that competent senior and field commanders were judiciously deploying their sons and doing everything they could to save lives amid the dirty business of war.

In the effort, Huston and his camera crew of six intrepid men created a startling, shocking, and unsettling antiwar film. While that screening for the officers was underway, Huston began to realize that he had stirred up a dust cloud of controversy. He reflected some years later, “A number of high-ranking officers, including a three-star general, were present at the first showing of The Battle of San Pietro. About three quarters of the way through the picture the general got up and left the projection room. It was naturally assumed that he was displeased with what he saw, and it was incumbent upon the rest to show their displeasure also. But, of course, they had to do so by rank, according to protocol. It wouldn’t do for a lieutenant colonel to go stalking out before a brigadier general. The general was followed about a minute later by the next-ranking officer, and then one by one they filed out, with the low man on the totem pole bringing up the rear. I shook my head and thought, ‘What a bunch of assholes! There goes San Pietro.’”

The offended sensibilities of a group of stateside Army officers was nothing compared to the real suffering the soldiers of the 36th Infantry Division had actually experienced at San Pietro; many of them had apparently lived and died on camera. The 36th Division, a National Guard outfit comprised mostly of Texans, traced its already storied lineage to the Republic of Texas in the 1830s, and at San Pietro the men of its three regiments, the 141st, 142nd, and 143rd, enhanced the reputation of the division with their heroic performance.

Despite the old saying that all roads lead to Rome, the Allied Fifth Army and its commander, Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, were concerned with only one route to the Eternal City in December 1943, and that was Highway 6, which traversed the mountainous country of southern Italy into the wide valley of the Liri River and on to the Italian capital city, passing San Pietro on the way.

While Rome was 115 miles from San Pietro, the Germans were sure to contest every yard, fortifying mountains, hills, and draws, setting up antitank guns, machine-gun nests, and roadblocks that would stifle traffic wherever they thought practical. Col. Gen. Heinrich-Gottfried von Vietinghoff-Scheel commanded the German Tenth Army, a veteran force still full of fight after weeks in action since the Allies had come ashore in Italy at Salerno in September.

On December 1, the Fifth Army launched a combined offensive to capture Rome and crack open the German defensive front for good. American forces were to advance through the Mignano Gap, cross the Rapido River, and occupy the town of Frosinone about 50 miles south of Rome. After Frosinone was taken, an amphibious landing, Operation Shingle, was to take place at the resort town of Anzio about 35 miles south of the capital city. In the east, the British were expected to drive toward Rome, and the two forces could link up to take the first Axis capital to fall and cut off the escape route of thousands of German troops in the process.

Beyond the fact that the Italian Campaign needed energy, the window of opportunity for a successful Allied offensive was rapidly closing due to events elsewhere. Operation Overlord, the long-awaited invasion of Nazi-occupied Western Europe, was scheduled for June 6, 1944, and the timetable required that all available landing craft be released for Overlord by the end of January. Without landing craft, the Anzio operation could not go forward. Further complicating the situation were the inhospitable terrain and the simple fact that Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, a Luftwaffe officer turned ground commander and now in charge of all German forces in Italy, was conducting one of the most brilliant defensive campaigns in military history.

Thus far, Kesselring had commanded a skillful fighting withdrawal up the boot of Italy, fortifying several strong defensive lines and taking full advantage of the rugged terrain. For the Americans, the capture of San Pietro and the town of San Vittore just to the west would allow them to press forward to the town of Cassino, which anchored Kesselring’s formidable Gustav Line.

Early in the offensive, the combined American-Canadian 1st Special Service Force and the British 56th Division captured Monte Camino and Monte la Difensa, and the 142nd Infantry Regiment took Monte Maggiore, securing the entrance to the Mignano Gap.

The Germans chose the time and place of any pitched battle, and each mountain or hilltop presented a potential obstacle for the advancing Allies. As they moved forward, the troops of the 36th Division drew up around Monte Lungo, a natural sentinel along Highway 6 and the rail line into Rome. To the northeast, Monte Sammucro towered nearly 4,000 feet over the roadway. Just as the grade up the slope of Monte Sammucro began to steepen appreciably, the village of San Pietro was situated to dominate Highway 6 and the valley below for miles in any direction.

After occupying Monte Maggiore and nearby Monte Rotondo, American commanders were optimistic that little German resistance would be encountered at San Pietro. They speculated that the enemy might already have begun to pull out of the town, retiring northward to avoid being cut off and surrounded by the American advance. German commanders had indeed intended to retire, but heavy rains had swollen the Rapido and Garigliano Rivers beyond floodstage, impeding the movement of troops and vehicles. Then Adolf Hitler intervened. The Führer decreed that San Pietro should be held as long as possible, and the tough panzergrenadiers in the vicinity held their positions, ready for a fight.

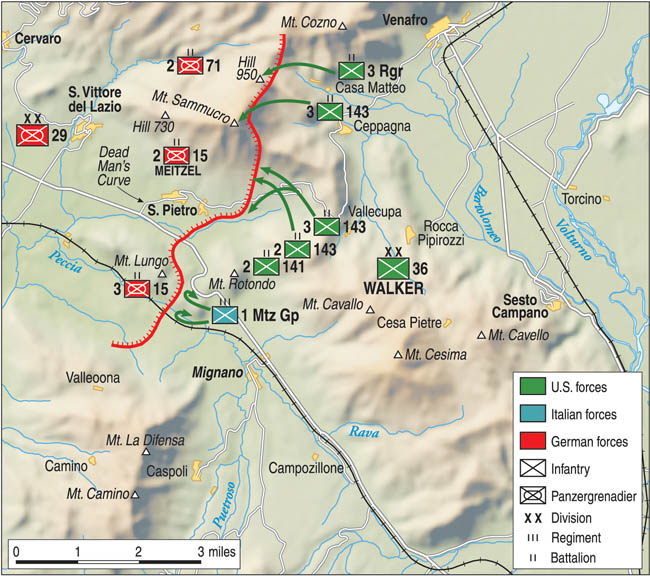

The 2nd Battalion, 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment, 29th Panzergrenadier Division held the town of San Pietro, and two additional battalions—the 3rd Battalion, 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment and the 2nd Battalion, 71st Panzergrenadier Regiment—occupied Monte Lungo and Monte Sammucro.

When American intelligence officers discovered that German forces were still in the San Pietro area in force, they failed to comprehend just how bloody the battle for the town would become. The village’s stone buildings, steep terrain, and narrow approaches constituted a natural fortress.

Eminent historian Martin Blumenson wrote, “Expecting Monte Lungo to come into Allied possession easily, Allied commanders looked toward San Pietro. What had escaped their intelligence officers was how inaccessible San Pietro really was. There were simply no good approaches to the village, where houses provided stout stone walls for weapons emplacement. Separated from Monte Rotondo and the Cannavinelle Hill by a deep gully and sitting above the Ceppagna road San Pietro could be entered only by way of cart tracks and trails across the ravine-scarred face of Monte Sammucro. Nor was it evident to Allied intelligence how important San Pietro was for the observation it gave of Monte Lungo and the trough that carried Highway 6 to Cassino.”

Tactical planning for the effort to take San Pietro was formulated by Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes, commanding the U.S. II Corps, and Maj. Gen. Fred L. Walker, commanding the 36th Division. Keyes reasoned that the newly arrived Italian troops of the 1st Motorized Group might benefit from a morale-boosting victory, particularly since their country’s recently installed government had turned against its former Axis partners and joined the Allied cause. Keyes assigned the Italians to capture the summit of Monte Lungo, while two battalions of the 143rd Infantry Regiment were ordered to take Monte Sammucro, drive around the mountain, eject the Germans from San Pietro, and dash on toward San Vittore.

On the morning of December 8, the Italians began their trek up the slope of Monte Lungo. Marching two battalions abreast, they soon stumbled into the prepared positions of the 3rd Battalion, 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment, their guns zeroed in on the approaches. Within hours, the effort had come apart, the Italians suffering 84 killed, 122 wounded, and 170 missing as they withdrew in disorder down the mountainside.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 143rd Infantry Regiment overran the German positions on Monte Sammucro just as the sun was rising. Reinforcements from the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment arrived, and the Americans dug in, fending off repeated counterattacks launched by the 2nd Battalion, 71st Panzergrenadier Regiment for several days. American troops occupied adjacent Hill 1205, and the 3rd Ranger Battalion captured Hill 950 briefly before a German counterattack pushed them off. On December 9, the Rangers regrouped, charged the summit, and then held the hill.

Advancing directly on San Pietro, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 143rd Infantry advanced only 400 yards before the 2nd Battalion, 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment stopped them cold. By December 10, the 1st Battalion had lost half its strength, reduced to only 340 combat-effective infantrymen.

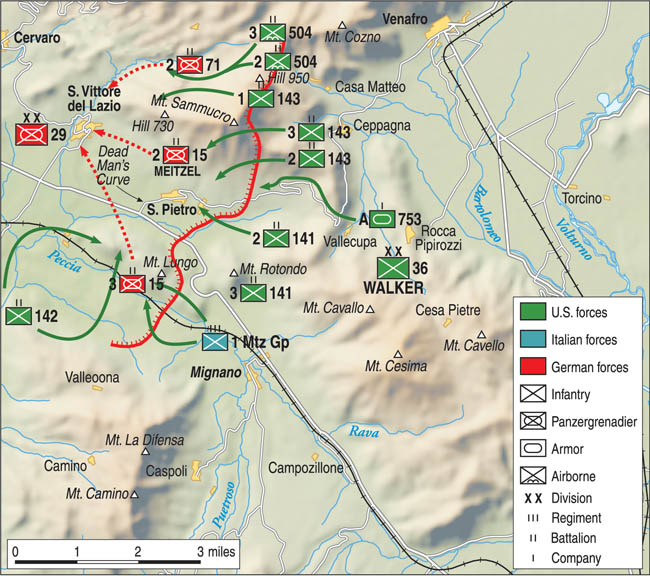

Taken aback by the ferocity of the German defense, American commanders staged another offensive to take San Pietro on December 15-17. General Walker saw opportunity in the capture of three small hills about a mile west of Hill 1205. If the 36th Division could occupy those hills, the German garrison in San Pietro might be flanked, and the entire 3rd Battalion, 15th Panzergrenadiers would be marooned on Monte Lungo.

Walker assigned the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 1st Battalion, 143rd Infantry with capturing the three hills before sunup on December 15. The direct thrust at San Pietro would soon follow, with tanks of the 753rd Tank Battalion striking from the east and the 141st Infantry from the north near Monte Rotondo. With these advances underway, he hoped that the German defenders in San Pietro would be too busy defending themselves to provide any fire support for their comrades holding Monte Lungo. Therefore, elements of the 142nd and 143rd Regiments would take advantage of the opportunity to attack Monte Lungo from the west.

The use of tanks in the mountainous regions of Italy was always problematic. However, General Clark wanted to get the armor into action as quickly as possible around San Pietro and General Keyes agreed. To that end, Clark sent Fifth Army Operations Officer Brig. Gen. Donald W. Brann to Walker’s 36th Division headquarters with the strong suggestion that tanks be employed at the first opportunity. Brann questioned Walker about the feasibility of using tanks at San Pietro and was told bluntly that the ground was not favorable. Nevertheless, he understood the directive and agreed to try.

The result was a magnificent disaster. Any vehicle, armored or otherwise, attempting to approach San Pietro was required to utilize a narrow road that was barely wide enough for two-way traffic. A few trails intersected with the road, but these were quite narrow, no more than eight feet across. The road itself was fraught with risk for any tank under fire. Four choke points would undoubtedly be troublesome, and these included culverts of 10 and 15 feet along with a pair of bridges. Tanks passing through the area would be vulnerable to a torrent of defensive fire. To make matters worse for maneuver, the slopes of Monte Sammucro were terraced with retaining walls as high as seven feet between the terraces.

Combat engineers went to work on December 11 to improve the situation as best they could. They demolished walls on some of the terraces and blasted paths for some of the tanks to utilize in descent after they had worked their way into the hills above the town. The lead tank clanked forward after dark and immediately lost traction in the rain-soaked terrain, throwing a track. The commotion attracted the attention of German artillerymen, who began dropping shells into the area. The effort was soon called off.

On December 15, while the 1st Battalion 143rd Infantry and the 504th Parachute Infantry made several unsuccessful attempts to capture the three hills Walker had assigned to them, 16 M4 Sherman medium tanks of Company A, 753rd Tank Battalion, a company of supporting infantry, and a borrowed British Valentine tank equipped with a prefabricated bridge rumbled down the road at midmorning. The original plan to assault the town from two directions quickly fell apart when the lead tank found the road blocked and was redirected across the terraces, where it went on to destroy a German command post and several machine-gun nests.

Late to respond to the threat, German artillery began firing, and the three following tanks found their trail blocked by the hulk of a knocked out German PzKpfw. IV tank. These tanks could not follow their leader since the terraces in their area were too steep. Instead, they were ordered to retire to the main road and shell the town in support of the upcoming infantry push. About 1,000 yards from San Pietro, the first of the three tanks reached a bridge, crossed, and was immediately set ablaze by a German antitank round. The second Sherman moved across the bridge and was blasted by two shells, erupting in flames. The third tank was destroyed by three shells before it even reached the bridge as the German gunners found the range. The next three Shermans in line were disabled by mines.

One M4 fell off the edge of the road and flipped over, landing five feet below. Three more threw tracks. Another Sherman attempted to follow the lead tank across the terraces but lost traction and turned over on its side. One Sherman crashed into a second that was already disabled. The Valentine remained unscathed, but it was trapped by crippled Shermans and abandoned. Only four of the 16 Shermans that began the attack returned undamaged. Five of the 12 damaged tanks were later recovered and repaired.

Lieutenant John Huston of the Signal Corps watched the unfolding debacle. Although his eyewitness account differed somewhat from the official version, his impression was noteworthy. “This was a most ill-conceived plan undoubtedly conceived by someone back of the lines who didn’t know the first damned thing about the terrain around the village. The right side of the road was a mountainside, and the other side was a drop-off down the mountain. Once committed, the tanks couldn’t turn around…. We could see the tanks burning and exploding, and men running and trying to hide. After it was over, we crept forward and photographed the disastrous results. It wasn’t pretty. There was a boot here—with the foot and part of a leg still in it—a burned torso there….”

Sergeant Ray Wells of the 2nd Battalion, 141st Infantry, the outfit that the tanks were supposed to support, witnessed the armored assault as well. “I was watching them from what seemed to be a mile away,” he remembered. “I saw the tanks go up that road. They were moving slowly because of the curves, and they were hitting mines. When they got to where the German 88s could knock them out, the tank behind would just push aside one that was hit and just keep on going. The tankers were a bunch of brave people. That’s for sure.”

Lieutenant Colonel Milton Landry commanded the 2nd Battalion, 141st during the San Pietro fighting and remembered his unit was ordered that day to interdict any German resupply effort from the west. The 2nd Battalion got going around noon.

“We had companies E, F, G, H, and the battalion headquarters company,” Landry commented. “I lost three company commanders in the first 30 minutes. Captain Charles Beacham was shot through the cheek, and Ray Wells pulled him out of the line of fire. Captain [Charles] Hamner was killed, and Captain John Chapin was also wounded. I remember the fact that we had men falling left and right all the way through. We attacked all afternoon and up into the night. We lost so many men that Company L was sent to join us. When we were finally ordered to pull back, there were 42 of us left in the battalion plus the extra rifle company. I would say we had close to 800 men when we started.”

Landry led from the front and was wounded three times during the fighting on December 15-17, later receiving the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism. “The terrain facing San Pietro was terraced almost the complete distance from Monte Rotondo to the town itself, and most of the terraces had a wire fence on top and near the edge,” he recalled. “In almost every case the enemy had installed a booby trap of some kind…. We had to figure a way to eliminate this hazard, and we came up with an almost foolproof plan. Two of the larger men would lift me up so I could take hold of the tripwire, and when I gave the signal they would drop me so I could pull the wire down with me, explode the booby trap and at the same time be protected by the rock wall which bordered the terrace.”

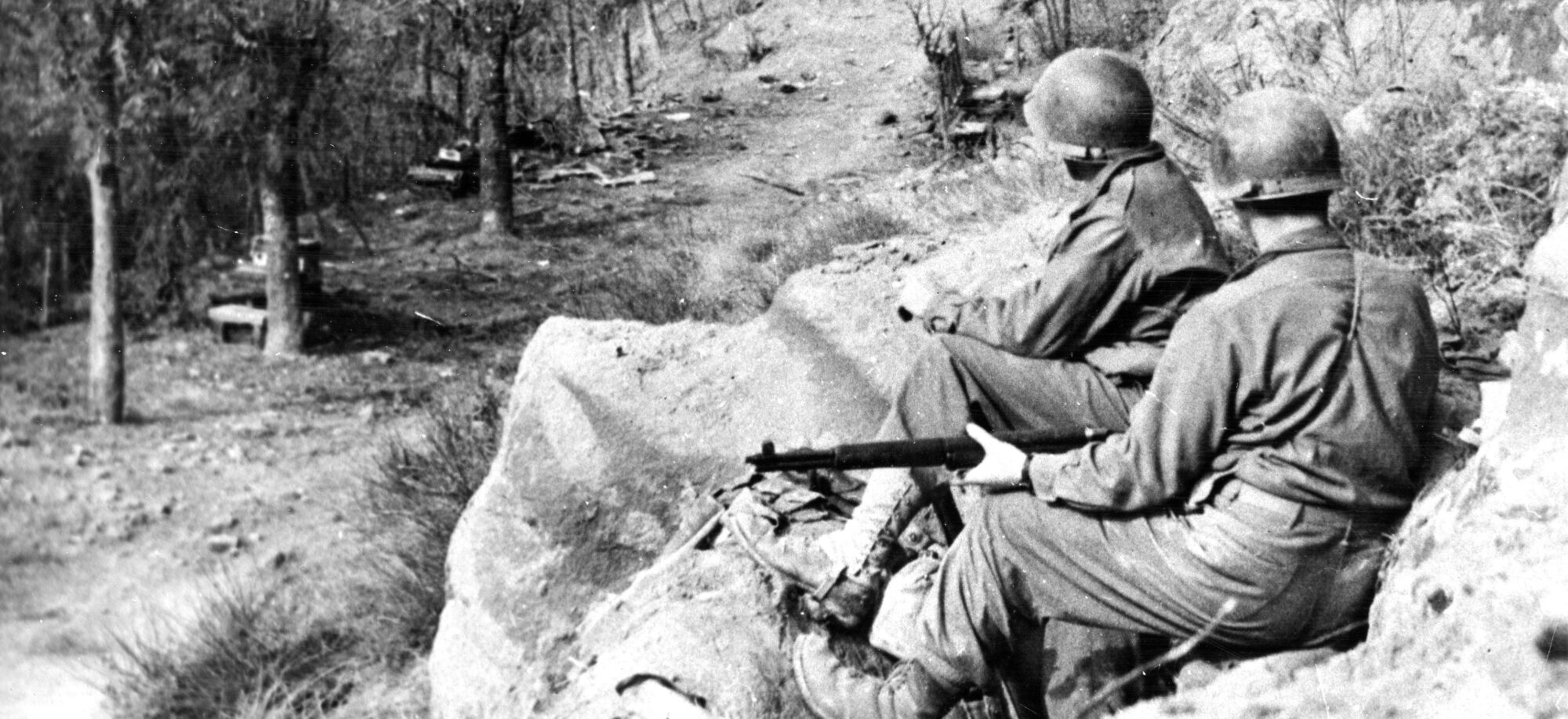

The German defenders had had plenty of time to dig deep foxholes and entrenchments in the vicinity of San Pietro. Often, the Americans had to advance to point-blank range to root them out of strongpoints. “You couldn’t see them,” said Landry. “You had to go up and across one terrace, and then there was always another one. You could look in at the wall and see what you thought was a black rock, but it wasn’t a rock. It was a hole with a machine gun on the other side where the Germans had dug a big pit and connecting trenches where they could crawl back and forth. They covered the tops of the pits with railroad crossties, dirt and plants. They could sit in there with wine, black bread, and cheese that comes out of a tube like toothpaste and wait for us.”

Landry was also at a disadvantage during his attack, relying on highway maps purchased by his battalion surgeon in North Africa. Most of the intelligence had identified the German positions as antiaircraft emplacements, but this proved to be untrue as the soldiers of the 36th Division pushed toward San Pietro. “The highway maps were just as good as our government maps,” Landry remarked. “The scale on them was terribly small, though. You could make a line on the map with a pencil, and crossing that line on the ground would take 200 or 300 yards. On the map that distance was only as thick as the pencil lead. We would get copies of Life magazine, and they would show us not having moved at all. We would fight for two or three weeks up and down mountains, and on the maps it looked like we hadn’t advanced.”

Strangely, when Landry was leaping for cover from an incoming German shell, he discovered a brass plate driven into a rock by surveyors of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. “I was laying my head on the plate, and it meant that there were good maps of the entire area. We just couldn’t get them because nobody knew we had them,” he said.

Wells recalled, “Most of the men in my squad were wounded right away. The Germans were looking right down our throats all the time, and the snipers were pretty accurate. A lot of the people I saw were shot right between the eyes. Our medics had helmets with red crosses on them, and I saw some of them shot by bullets that went right through the middle of that cross.”

Wells ordered suppressing fire against several buildings where snipers were believed to be holed up. “The enemy was in the houses upstairs, shooting out the windows at us,” Landry related. “Raymond [Wells] was leading a heavy machine gun squad, and I think he was the only one that had a machine gun left. Originally the crew had a big water-cooled machine gun. He abandoned that and picked up a one-man light machine gun. Later, after we had done our job, he acted as a rear guard for our withdrawal back to Monte Rotondo.”

It is likely that Wells shot at least three German snipers during the brawl, and he probably saved dozens of his comrades in the process. Firing that machine gun in the heat of combat, however, he was never sure of the effect. “You just go on to the next one and do your best, but I never felt like going over and looking.” More than half a century after his heroism at San Pietro, Wells received the Silver Star in recognition.

As the 2nd Battalion, 141st was heavily engaged, the 2nd Battalion, 142nd and 3rd Battalion, 143rd worked their way around Monte Lungo, crossing Highway 6. As the frontal assault against San Pietro got underway, they captured the summit of Monte Lungo, fighting off a determined defense by the Reconnaissance Battalion of the 29th Panzergrenadier Division. By the morning of December 16, most of the high ground in the area was under Allied control, the Italians taking the last strongpoints along the ridgeline.

The fall of Monte Lungo sealed the fate of the San Pietro defenders. With American troops also atop Monte Sammucro, the evacuation route along Highway 6 might be cut. German commanders prepared for a withdrawal, believing they had done everything possible to hinder the Americans’ progress toward Rome. They launched a sharp but diversionary counterattack to cover the withdrawal of the 29th Panzergrenadier Division from the town on the night of the 16th. The 143rd Infantry Regiment trudged into San Pietro the next day, after absorbing 1,000 killed and wounded. The Americans found the village shattered and 300 civilians dead.

John Huston’s camera crew had followed the 143rd Infantry Regiment throughout the San Pietro action. “Previous to our first attack, I had interviewed—on camera—a number of men who were to take part in the battle,” Huston later wrote. “Some of the things they said were quite eloquent: they were fighting for what their future might hold for them, their country and the world. Later you saw these same men dead. Before placing the bodies in the coffins for burial, the procedure was to lay them in a row in their bedrolls, make positive identification—where possible—then cover them. At that point, it was necessary to lift the body up, and I had my cameras so placed that the faces of the dead came right to the lens. In the uncut version I had their living voices speaking over their dead faces about their hopes for the future.”

Top Army brass demanded that Huston’s startling drama The Battle of San Pietro be banned from public screening. The film was heavily edited, but even then it was rarely shown until some time after World War II was over.

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall watched the film and took a significantly different view of its impact and value. He stated, “This picture should be seen by every American soldier in training. It will not discourage but rather will prepare them for the initial shock of combat.” Huston expected to become persona non grata in Army circles. Ironically, he received a promotion to the rank of major and was decorated for meritorious service.

During the 1980s, roughly 40 years after the events at San Pietro, author Madge Mackenzie interviewed Huston twice, writing in the New York Times: “The Battle of San Pietro stands alone in the history of documentary filmmaking. Presenting the battle in the Liri Valley as a costly continuing campaign rather than in retrospect as a strategic victory, it is the only complete record of an infantry battle. Filmed with … 35mm hand-held Eyemo newsreel cameras in the midst of gunfire, its camera angles are low and from the ground. Shots are grabbed, immediate, unexpected. It is a vivid, complete record….”

To this day, film historians dispute Huston’s assertion that The Battle of San Pietro includes actual combat footage and even assert that “dead” soldiers are miraculously seen alive in archival reels after the combat scenes were filmed. Nevertheless, the film makes a strong antiwar statement and stands out in the history of documentary filmmaking.

Landry recalled the activities of other combat cameramen with the 141st. “They were in our battalion area, and when one of them would get hit their camera would keep filming and roll down the hill. I saw film of my mortar crews apparently lying down on the ground and firing their weapons. Actually, it was the angle of the hill, and when they turned their cameras it made it look like the guns were turned flat.”

Lieutenant Colonel Landry offered his own unvarnished assessment of the San Pietro attack, which had cost his battalion so dearly in lives. “It was a stupid operation,” he said bluntly. “My battalion was used to attacking at night. For us to attack in daylight across a valley and up a hill where the Germans had been fortified for a long time was suicidal. I was fortunate to have a battalion that stuck with me and went all the way. When it was over there weren’t many of them left, but the ones that were left were doing their job.”

As gut wrenching as the battle at San Pietro had been, agonizing fighting still lay ahead for the 36th Division, particularly during disastrous attempts to cross the rain-swollen Rapido River and attacks on the Gustav Line in January 1944. The planned amphibious landings at Anzio went forward, but Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, commanding the Allied VI Corps, chose to consolidate his beachhead rather than dash forward on open roads to swiftly capture Rome. Kesselring utilized the time to counterattack and contain the Anzio beachhead until May 23. Rome did not fall until June 4, only two days before the Allied landings in Normandy shifted world attention from the Mediterranean Theater.

After the war, the town of San Pietro was rebuilt some distance away from its original location. The destroyed buildings were left, however, as silent testimony to the terrible fight there in 1943.

Huston’s two other landmark documentary films, Report from the Aleutians and Let There Be Light, stirred controversy of their own. The footage of the Aleutian campaign depicts an air raid on Japanese positions, and the film was nominated for an Academy Award in 1943. Let There Be Light depicts the treatment of veterans suffering psychological illnesses at a hospital on Long Island after the war. The film itself was confiscated and remarkably banned from public screening until 1980. Let There Be Light and The Battle of San Pietro remain the only works of their kind to have ever been banned by the U.S. War Department.

Author Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History magazine. He is also the author of numerous books and articles on military history, including West Point 1915: Eisenhower, Bradley and the Class the Stars Fell On and Appomattox: The Last Days of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.