By Stephen D. Lutz

Prior to the summer of 1941, the United States Marine Corps did not want them. The Navy barely tolerated them in restricted capacities as cooks, waiters, servants for officers, and dockside stevedores. The Army, too, thought they were only good enough to tackle menial duties and perform manual labor.

On June 25, 1941, after black labor activist A. Philip Randolph threatened to embarrass President Franklin D. Roosevelt with a massive march on Washington to protest the military’s policy of racial segregation, America’s commander-in-chief (with his wife’s urging), signed Executive Order #8802 mandating that all services accept qualified African American enlistees-draftees. For the first time in 167 years, the U.S. Marine Corps would be receiving black Americans.

In 1936, 57-year-old, four-star general Thomas Holcomb became the Corps’ 17th commandant, beginning his seven-year reign over all things Marine Corps. Like most white officers, Holcomb rigidly insisted that blacks had no place in his Corps as they tried to “break into a club that doesn’t want them.” As the Corps frowned upon the U.S. Army as an inferior, poorly trained, lesser-motivated service (but one that was accepting black draftees and enlistees in segregated units), Holcomb declared, “The Negro race has every opportunity now to satisfy its aspirations for combat in the Army.”

With the Corps responding as an offshoot to Navy authority, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox agreed. Attempting to integrate African Americans became an overwhelming challenge for the Marine Corps’ Division of Plans and Policies as part of its Personnel Services branch. In charge of those affairs was a University of Southern California graduate, Colonel Ray Albert Robinson, a resident of Los Angeles, California.

Considering his background, Robinson had little acquaintance with Jim Crow laws that had dominated America’s southern states since Reconstruction. He had to follow the traditions of his era when Jim Crow spoke aloud with timeworn prejudices. Robinson said, “It [integration] just scared us to death; we’ve never had any [black recruits]. We didn’t know how to handle them. We were afraid of them.”

The bottom line from Robinson was, “Eleanor [Roosevelt] says we gotta take in Negroes.” Succumbing to pressure from on high, Holcomb made his own preparations for their admittance with his March 1943 “Letter of Instructions #421,” in which he made it clear no African American Marine would ever become an officer, nor would any black Marine outrank any white Marine.

If a black buck-sergeant came upon a white private first class, that private would not have to do a thing that sergeant told him. African American noncommissioned officers could only direct African American Marines, and black Marines had to follow all orders of any NCO outranking them.

One Marine senior commander had his own viewpoint on these racial issues as the Pacific War widened. Maj. Gen. Charles Fredrick Berthold Price graduated from Pennsylvania Military College and became a Marine in 1906. When notified that an African American unit was bound for his area, Price flat out refused to accept it. In spite of that, in October 1943, a ship carrying two African American ammunition companies pulled into port. Price refused to allow them to disembark, keeping them aboard ship for two days before sending them away. Price’s prejudices raised the legitimate question: Who would fight and perhaps die in a war for a country under those conditions?

But the wheels of at least partial integration had been set in motion.

With war on the horizon, in September 1941 the government began constructing a new training facility for an expected increase in Marine recruits; it would be another year before Marine Barracks, New River, North Carolina, would become known as Camp Lejeune (named for the World War I Lt. Gen. John A. Lejeune, the Corps’ 13th commandant).

Camp Lejeune became the home for the Corps’ future 10,000 African American recruits. Although at least a dozen black Marines had served with the Marines during the Revolutionary War, the Corps went lily white from 1798 until August 26, 1942, when Howard P. Perry of Charlotte, North Carolina, appeared at Camp Lejeune’s gates, quickly followed by 12 others. (The Marines in World War II did accept some Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans—the “Code Talkers.”)

As more African American Marine recruits arrived and climbed down from trains and buses, much of the site was still a construction zone, in the process of expanding from its original 110,000 acres of land to today’s 244 square miles.

Instead of proper barracks, though, the original group of future black Marines found tents, then shanties—virtually so cheap that many said the building material must have been prefabricated cardboard; some men found it easy to poke bayonets through the walls. Eventually, corrugated steel Quonset huts came; more brick-and-concrete buildings followed.

At the north-central point of the camp sat a spit of land jutting out into Stones Bay that was surrounded by water on three sides. This five-square-mile peninsula became known as Camp Montford (today’s Camp Johnson).

At the time, it was more swamp and marsh than dry soil and was inhabited by venomous and nonvenomous snakes, as well as panthers, alligators, and any other swamp creature that could survive such an environment.

In the six months after Pearl Harbor, African American recruits came into military service as high school graduates and as high school dropouts. Some came as college graduates and others as college dropouts. Some had exposure to ROTC training, while others had gone no farther than the Boy Scouts. A vast number were skilled tradesmen—carpenters, electricians, plumbers, professionals, shop owners, etc. One had a civilian pilot license.

Just as many were illiterate, unemployed, and looking for a steady paying job. Some joined for the attraction of the Marine Corps’ fancy dress blue uniform, while others claimed it was the patriotic thing to do in wartime. A few followed in their fathers’ or grandfathers’ footsteps who were veterans of the Spanish-American War or World War I. Some, no doubt, believed that they would be better treated after they returned to civilian life if they could claim the title of having been a United States Marine.

On the whole, their birth years ranged from 1923-1925. The youngest enlistee, at age 16, passed himself off as 18. Some came as prior-service Army or Navy. Those who came from north of the Mason-Dixon Line knew about the segregated South and had themselves been discriminated against but had not experienced the full force of “Jim Crow laws.” Those from the South knew exactly what those laws meant: discrimination, isolation, belittlement, harassment, humiliation—and sometimes death.

Many African Americans shared their stories after the war. When Herman Darden, Jr., walked into a Marine recruiting station in Washington, D.C., it took the recruiting sergeant nearly 10 minutes to look up and acknowledge his presence; it was intentionally done.

Recruit Obie Hall started his Marine career from Boston north of that invisible but very real wall of segregation: the Mason-Dixon Line. His free train ride included a sleeping berth—until he reached Washington, D.C. There an African American conductor evicted him from that car’s comfort, insisting that Hall join the rear car(s) that were restricted to Negroes—cars that were more congested and less accommodating. (Hall encountered a more compassionate conductor who found him an open berth.)

A year later, John R. Griffin started out from Chicago with the same comforts Hall had. Once crossing the invisible line, though, he lost his berth and wouldn’t get it back.

Another recruit came out of New Jersey where he was one of three African Americans in a well-integrated high school; he knew nothing of Jim Crow. Upon crossing that line, he found a drinking fountain labeled “Colored.” He stood there turning the water on and off, waiting to see what colors would come out. Eventually, a sergeant explained the realities of life in the segregated South. Wherever they originated, the first 600 black recruits reached Marine Barracks, New River, North Carolina, during the summer of 1942.

Camp Montford was 12 to 14 miles from the pristine beaches of the main base, where the Corps practiced beach-landing assaults. When not engaged in that activity, white Marines found ample opportunities to lounge about the sunny beaches as if on vacation. Those African Americans assigned to Camp Montford, however, were restricted from the beaches for anything other than official training exercises. In effect, for recreational purposes those beaches became “Whites Only.”

One exceptional missing factor was medical services. Going into World War II, the standing rule was established by Jim Crow—and then upheld by all military authorities—that only black medics, nurses, and doctors could treat/attend to black military personnel, while only white medics, nurses, and doctors could treat/attend to white patients. It would be months before the Navy even started accepting African Americans into corpsman classes.

It was discovered that many succeeded in passing their induction physicals while infested with hookworms, venereal disease, and other lingering ailments that intensified at Camp Montford. Without proper medical inspections, health and welfare conditions surrounding sanitation of food services, latrines, showers, and living quarters became a petri dish of staphylococcus and salmonella. Changes took place after July 20, 1943, when the Navy finally started training African Americans as corpsmen.

As growing numbers of black recruits began their 180 days of basic and advanced training, there were things the Corps did not tell them. Regardless of how their ranks swelled, in the end there would be no all-black combat units, and no African American Marines were assigned to white combat units. The Corps deliberately found—even created—special jobs/positions/units intended to keep African Americans out of combat.

The theory was that blacks, as a whole, were cowards and were intellectually inferior to whites and that, if faced with the reality of combat, they would fail in their duties. The theory also meant that the Corps would not have to invest heavily in their advanced infantry combat training. The black troops would get the basics, of course, but the advanced individual training would be minimized, allowing only white Marines to push forward and carry the burden of the war effort—and accrue the glory and medals that were their birthright.

Being an unknown factor, these black recruits were forced to enhance their experiences themselves. For those assigned to the 51st Defense Battalion, the Corps’ first black unit, they supplemented their training on their own. Arvin L. “Tony” Ghazlo imparted his acquired jiu jitsu skills; another black Marine, Ernest Jones, taught his comrades his mastery of judo. Those with higher educational skills tutored comrades struggling to read and comprehend training manuals.

The Corps did everything it could think of to keep weapons out of the hands of African American Marines and away from the fighting. This extended to defense battalions defending naval bases and airfields with 155mm cannons for long-range targets off shore, 90mm, 40mm and 20mm guns for antiaircraft artillery, then a wide array of small arms and machine guns.

At the war’s beginning, the Corps had 18 Defense Battalions designated 1st thru 18th, but it was decided that two more were needed; they were designated the 51st and 52nd Defense Battalions on August 18, 1942, and December 15, 1943, respectively, and were staffed by black Marines led by white officers.

Although deployed to the Pacific, neither would ever see combat. The two battalions spent the war sitting on the captured islands/atolls of the Ellice Islands in the Gilberts, Funafuti-Nukufetau, Nanomea, Eniwetok, Majuro, Roi, and Kwajalein. Each battalion had only a single alert: the 51st of a suspected enemy submarine and the 52nd of in-bound airplanes. Both warnings proved false. Both battalions came home after the war without ever firing a shot against the enemy.

As the Pacific War expanded, another need came to light. As one island was approached, battled over, then claimed, that entire process demanded an unending flow of supplies. Handling those supplies—loading ships at the docks and offloading them where the supplies were needed—became an inefficient affair, for combat battalions would have to be pulled off the front lines and rotated to the rear to perform the task. The black Marines seemed to be an ideal source of cheap labor for just such a purpose, and thousands of them were assigned as stevedores to load and unload ships on docks in the United States and the Pacific.

A job as easy as that, the Corps figured, could be taught within three or four weeks. Over time, 49 Marine depot companies would be formed, sequenced 1st through 49th Depot Companies. Each company was comprised of 150-170 black Marines.

Although such supply activities were essential for the war effort, the fact that they were used as little more than beasts of burden rankled many black Marines. They had joined to fight a war, not haul crates or drive forklifts.

A glitch arose with the fragile handling of ammunition, shells, explosives, white phosphorus, timers, fuses, etc. Such material was too delicate a matter to entrust to anyone ill prepared to handle it. So, the Corps created its third African American entity: the Ammunition Companies.

Completely separate from the depot companies, the ammunition companies consisted of 250-260 Marines each; by war’s end they would be numbered 1st through the 12th. All had three white officers with African American NCOs and lower ranks. Due to the delicate (and potentially deadly) nature of their work, the ammunition companies had a more intensive advance training schedule that lasted up to eight weeks.

Although not trained for combat, these depot companies often found themselves under fire when they were required to land on islands held by the enemy, and all of them participated in combat whether the Corps intended it or not. That would be done by direct face-offs with the enemy on Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

On June 15, 1944, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions stormed ashore on Saipan; assisting the 2nd was the 19th Depot Company, while the 4th was supported by the 18th and 20th Depot Companies. More than 75,000 Marines took part in this battle, with 800 being African Americans.

The depot companies had no vehicles of their own; they were required to use the motor-pool vehicles of the units they supported, but the ammunition companies did have their own trucks, jeeps, and trailers. During the initial two hours of the landing on Saipan, the 19th Depot Company was ashore and setting up its supply distribution point within range of Japanese snipers and mortar crews.

As the white Marines fought their way inland to create a solidified front line, the 19th was as much in the midst of the shooting as any other Marine unit, firing furiously at the enemy whenever they came close. When not fighting, the black Marines were unloading supplies, bringing them forward, then carrying the wounded back—only to repeat the entire process.

For many of these white Marines at the front, this was their first time seeing a black Marine—or even knowing they existed. After aiding in the removal of wounded, those of the 19th formed antisniper reaction teams—one man to spot the shooter, and the other to pick him off.

One of the companies handling the forwarding of supplies on Saipan was led by Captain William C. Adams. His orderly, Private Kenneth J. Tibbs, became the first African American killed in action in the Pacific Theater—on the day of the landing. The next day Pfc. LeRoy Seals died from wounds incurred on the beach.

On that day, the 3rd Ammunition Company came ashore in an interesting manner. Its amphibious craft had pontoon-bridging material lashed to the craft’s outer side. Upon disembarking, they unleashed those planks and made a roadway to drive their own vehicles straight onto the beachhead instead of lugging their loads by hand.

The fighting on Saipan was vicious in the extreme, with no quarter asked and none given. Faced with the reality of losing their island fortress, the Japanese orchestrated a massive, late-night, do-or-die attack on July 7. This attacking force may have reached more than 3,000 dedicated soldiers—along with another thousand civilians—ready to die for the Emperor; almost everyone died. Although their 15-hour attack failed, the attackers inflicted 1,000 casualties on the Americans. And the depot companies were in the thick of the fighting.

The fight for Saipan officially ended on July 9, 1944, but there were still plenty of Japanese holdouts. Black Leathernecks Fred Ash and Turner Blount spent as much time as many others tracking down these holdouts, bringing them in, and guarding them as prisoners of war. In addition, the men of the 19th Depot Company partnered with demolition specialists to find and neutralize booby traps and mines.

Lieutenant General Alexander Vandegrift, who had replaced Holcomb as commandant of the Marine Corps in January 1944, was impressed by the courage and fighting spirit of the black Marines. “The Negro Marines are no longer on trial,” he declared. “They are Marines—period.”

The third week of July 1944 brought two more significant events. The conquest of Tinian took only eight days to accomplish, and taking part was the 3rd Ammunition Company from July 24-August 1, 1944, along with the 4th Marine Division. Within days, the 18th, 19th, and 20th Depot Companies were present. Between Saipan and Tinian, these four units received the Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon.

Simultaneously there was Guam from July 21, 1944—when the Corps’ 3rd Division arrived to reclaim it—to August 8, 1944. They had the help of three platoons of the 2nd Ammunition Company on the north beach while the Corps’ 1st Provisional Marine Brigade had the fourth platoon and the 4th Ammunition Company on the south beach. It was all an open invitation for sniper fire and bomb-laden, suicide sapper attacks. In one such satchel-laden attack by Japanese infiltrators, the 4th Ammo Company stopped a dozen attackers dead in their tracks. Even though the island was labeled as “secured,” an estimated 1,000 enemy holdouts remained hidden away on the island that would have to be ferreted out.

Private First Class Luther Woodward made himself a legend with his tracking abilities. On at least three occasions he discovered footprints on trails and followed them to their source before engaging the enemy. In one event, he led a handful of fellow Marines up to a cave knowing that an unknown number of enemy troops were inside. Woodward tossed in a grenade that chased one occupant out, making that an easy kill for Woodward. He then took his Ka-Bar knife, entered the cave, and killed a second soldier.

One trail-track discovery may have been an enemy scouting party sizing up the 4th Ammunition Company and preparing for a night raid. In the official records for August 8, 1944, Brig. Gen. Lemuel C. Sheppard, commanding the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, proclaimed that the 4th Ammunition Company “contributed in large [part] to the successful and rapid movement of combat supplies in this amphibious operation.”

The Marine Corps’ biggest mistake in the Pacific came on September 15, 1944: Peleliu. The Corps’ high command thought it would be a three- to five-day operation against the small island’s 10,000 defenders; it would not end until the final days of November and cost the Marines 1,800 men killed and 8,000 wounded—at 40 percent the highest casualty rate of any amphibious assault in American military history

The six-mile-long, two-mile-wide island had more than 500 natural caves that 10,000 Japanese soldiers had fortified, digging tunnels connecting many of them. This included an incredible number of ravines, crevices, and gullies that became deep foxholes in which to hide.

It would be the job of 16, 000 Marines of the Corps’ 1st Division, along with the 11th Depot and 7th Ammunition Companies, to pacify the island. Luckily for the 7th Ammunition Company, they had time to learn the jungle on Guadalcanal during precombat training sessions.

Lee Douglas, Jr., was with the 7th Ammunition Company, but getting ashore at Peleliu was impossible. The problem was the number of corpses floating in the water and covering the shore, preventing the landing craft from reaching the beach. The 7th spent two days on landing craft, throwing out nets and pulling them back in—filled with dead bodies—before an opening could be made for beach landings. Even then, he said, “We went in, we went with our rifles blazing.”

Lawrence Diggs was 19 years old when he landed on Peleliu with the 7th Ammo Company attached to the 1st Division’s 3rd Battalion. Diggs said the enemy had placed their mortars on tracks that could wheel in and out of cover. Because so many caves riddled the island, ferreting out the enemy became a concerted effort. One team would discover an occupied cave and fire into it. Getting no response to that, either a tank came up or a flamethrower was put in use.

Quite often the enemy moved along their tunnels just to pop out behind the Marines. Diggs said that, once everybody believed the island was secured enough, pup tents were delivered that accommodated three sleepers. By this time, hundreds of Japanese still hid out across the island.

One source of sustenance for these Japanese soldiers became their stealthy stealing of Marine rations at night. One night, while Diggs was in a tent with two others, he recalled a fellow black Marine named “Oliver” from North Carolina. That night a Japanese forager stumbled into their tent, and Oliver wrapped his hands around the intruder’s throat until he died. It took “a shot” for Oliver to release his death grip.

Diggs heard about another Marine on Saipan who spoke Japanese well enough to follow limited conversations. He would venture out on his own, creeping up on Japanese positions and listening in on their conversations. He would note their morale, how often they ate, what they ate, where they ate. He picked up on various positions as aid stations, watchpoints, and command points, and if any talk indicated a night attack. He then brought all of those conversations back with him.

On one return trip, he found an abandoned bicycle that he toted back to his lines. When close enough to be safe, he rode the bicycle back in. A famous picture exists of him on this bike in front of three comrades where the bike straddles a rail.

Reuben McNair was on Peleliu, also delivering ammunition. He was also told to go out and bring back the dead, but those of the 7th refused to do that; they brought back the wounded instead. McNair’s routine became the hauling of ammunition, joining his white comrades, shoulder-to-shoulder, in a firefight, carrying away the wounded, then returning with ammunition and fighting again.

At one point the white Marines he fought alongside were rotated out, with McNair saying proudly, “We had a group of white Marines, they was very happy, and as they returned back, they stated to [other white Marines], as what happened. They said ‘the Black Angels saved us.’”

When Peleliu was finally secured, the 11th Depot Company had suffered 17 wounded. That would be the highest number of casualties of any black unit across the Pacific Theater. In recognition of their service, Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, commanding the 1st Marine Division, officially noted how smaller “unit commanders have repeatedly brought to my attention the whole-hearted cooperation and untiring efforts exhibited by each individual” of the 11th Depot Company and 7th Ammunition Company.

The assault on Iwo Jima began on February 19, 1945. The plan called for the Corps’ 5th Division to come ashore first, then the 8th Ammunition Company, with the Corps’ 3rd Division coming in last. The 33rd, 34th, and 36th Depot Companies were there as well, but the 8th Ammunition Company would engage in far more direct combat than the whole 3rd Division.

By D-day + 3, all four depot companies were ashore. They would spend 32 days on the sulfuric island. Getting there included standard operating procedures instituted by all the military services throughout the war. Sections of each troop transport ship hauling black soldiers and Marines had improvised segregated compartments of “white-” and “colored-only” designations. Compartments were roped off as separate mess hall, latrines, and sleeping areas.

Many of the African American Marines found it more comfortable sleeping topside on an open deck than in cramped quarters below. While shipping over, they found themselves doing the vast majority of swabbing the decks, cleaning latrines, and KP than any white unit. Even if confined to restricted areas, it could not be helped if one Marine mingled in conversation with another Marine. One African American Marine spoke often and formed a bond with a Native American Marine—both of them being outcasts in white society.

Roland Durden gave his final perspective on such prejudices from the days of his training for Iwo Jima. When the 33rd and 34th Depot Companies were being shipped via rail from North Carolina to California, their train paused in New Orleans. This stop offered a Red Cross Doughnut & Coffee break. Attached to the train were two carloads of German and Italian prisoners of war. Durden said his captain was so racist that he ordered the Red Cross nurses to serve the prisoners first before the black Marines of the 33rd and 34th. The nurses flat out said “no” and that they would “serve our boys first.”

Then, on Iwo, Durden took a break from the intensity of the fighting with three black comrades. The fourth person was a white Marine who told them, “I was taught differently, but now I see you people; I have respect for you.”

Since Steven Robinson could not make it into the Tuskegee Airman program, even though he had a civilian pilot license, he ended up a Marine. Coming out of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he was that city’s second African American to join the Marine Corps. On the boat ride toward Iwo, he met one Native American Marine and had numerous conversations with him. Robinson said this Marine’s name was Ira Hayes.

Of all he saw and did on Iwo, Robinson recalled two specific incidents—one being the second flag going up on Mount Suribachi; whether he knew Ira Hayes was involved in it or not is unclear.

The other took place while an enemy force made a night attack. In the darkness, neither side could distinguish friend from foe. All they could do was point their weapons at muzzle flashes in front of them and fire. In this instance, as with many others, the battle devolved into hand-to-hand combat.

At other times, Marines fired blindly into the inky darkness as a source of comfort. On one pitch-black night, Robinson held the job of “sergeant of the guard,” being the on-the-spot supervisor for a number of outposts. He was summoned to Post #3 to see what a shooting incident was about. Stationed at that post was one of his Marine buddies named Booker James, holding a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). He had fired off a series of rounds. Upon his arrival, James told Robinson that there had been movement in front of him and swore it was enemy induced.

Robinson felt it was his responsibility to venture forth and determine what there may have been to shoot at. Robinson went forward on all fours, finding nothing alarming. Returning cautiously and walking upright, he tripped over a foot connected to a body. Closer inspection showed it being a dead Marine whom he left in place until daylight. Moving on, he stumbled over a second body of a dead Marine hidden by the darkness. Both had similar wounds being shot in the back.

At that point Robinson heard moans and groans of somebody severely injured. He found a third Marine barely alive, showing the same wounds the other two had: bullet holes in their backs. Booker James had unknowingly shot three Marines in the back; he would be forever convinced they were Japanese.

After reaching James, Robinson wanted him to go out so the two of them could bring in the wounded Marine. James refused, swearing that they were the enemy who was still prowling about. With great effort and many promptings, James finally went out, and the injured Marine was brought back in. He and the other dead Marines were white.

Eighteen days after the shooting ceased, according to the Corps, Robinson was driving a jeep on an errand. He came upon eight white Marines, many armed with pistols, indicating them to be either officers or noncommissioned officers. Others carried BARs and Thompson submachine guns.

Robinson halted to watch while the eight finished what they were engaged in. They surrounded a former enemy bunker that had caved in from relentless shelling. A handful of enemy soldiers emerged wearing nothing more than loincloths. It was plain to Robinson how malnourished, dehydrated, and weakened they were. He said they may have weighed 100 pounds at the most. There was no evidence of them retaining weapons. They were openly and willingly surrendering.

Once they were gathered and the eight Marines assured nobody else was coming out, all those surrendering were shot dead on the spot. With that done, all that Robinson could do was drive on his way.

Gene Doughty started out from Stamford, Connecticut, with a detour to New York City before reaching Camp Montford, then Iwo Jima. In their final desperation to inflict as much harm upon Americans of any color, a night banzai attack was launched virtually at the feet of the Marines. But it was a ragged, beaten force that emerged yelling from a series of undiscovered caves and tunnels. Many had no firearms; they attacked the Americans with homemade spears or clubs.

Archibald Mosley told about the youngest African American of any outfit in the Pacific Theater—a Marine everyone called “Babyface” for his youthful looks and exuberant attitude. And he was young; he had enlisted at age 16, and probably was not yet 17 when he landed with the 36th Depot Company on Iwo Jima, where he became the youngest black Marine to die in action.

Mosley recalled the night that the Japanese swarmed out of their caves and tunnels and attacked the 36th Depot Company in a suicidal banzai charge, badly wounding “Babyface.” Because the religious Mosley had ended each night with prayers, the members of his unit asked him to pray for the youngster whom everyone loved and tried to protect. But his prayers did no good.

Twenty-one-year-old Thomas Haywood McPhatter was halfway through Johnson C. Smith University—a historically black college—in Charlotte, North Carolina, when he dropped out in 1943 to join the Corps. His education and intelligence got him assigned to the 8th Ammunition Company, where he was a platoon sergeant and handled the complexities of explosives, fuses, detonators, and all things ammunition. His firm, no-nonsense leadership style earned him the nickname “Sergeant Steelhead.”

On February 19, McPhatter and his men were roaring into Blue Beach, plowing through surf that was coated with blood and the floating corpses of dead Marines. He recalled, “There were bodies bobbing up all around, all these dead men. Then we were crawling on our bellies and moving up the beach. I jumped in a foxhole and there was this young white Marine holding his family pictures. He had been hit by shrapnel, he was bleeding from the ears, nose, and mouth.” All McPhatter could do was lie there and repeat the Lord’s Prayer over and over.

Recovering from his shock, he organized his men and helped set up their ammunition depot at the base of Mount Suribachi in a depression that had been scooped out by the bulldozers of a Seabees unit. The site was easily in view of the enemy and well within range of rifle and mortar fire.

Direct hits by enemy mortars destroyed many of the caches of ammunition, setting them ablaze and exploding, killing black Marines and risking the lives of those who worked frantically to extinguish the flames. Ammunition shortages soon developed, and from time to time airdrops were required to replenish the supplies lost. There was always a high demand for hand grenades.

One such drop landed in the middle of no man’s land, so McPhatter led a squad out to recover what was dropped. Repeatedly the squad went and came back intact with all their personnel and misplaced ammunition.

On February 23, 1945, a group of six Marines from the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, passed by the 8th Ammunition Company with one member carrying a small American flag and heading in the direction of Mount Suribachi. Realizing what was about to happen and seeing that the group had no pole on which to hoist the flag, McPhatter quickly rummaged through a nearby scrap pile to find a suitable pipe or pole and gave it to the flag-bearing Marines.

Unfortunately, most history books make little mention of how this flagpole was found. The usual story is that the Marines passed by a rain-filled cistern and yanked loose a length of rusty pipe for their flagpole. Wherever the pole came from, 900 African American Marines—and almost every other Marine on Iwo Jima—saw their country’s flag go up that day.

The six men proceeded up the slopes of the 560-foot-high volcano—the highest point on the island—with flag and pole. The flag went up, but it was too small; a Marine battalion commander wanted a bigger flag put up for all to see across the island. The raising of that second flag by a different squad was filmed, and Joe Rosenthal’s photograph became the iconic symbol of Marine Corps history, as well as of American victory in World War II.

Photos do exist as the smaller flag was raised, came down, and the larger flag went up. What may be lost to history is the question of this first flagpole. Was it the pole McPhatter said he provided? Or was a second pole found, as some sources claim, and yanked from a rain-filled cistern? The historical record is unclear.

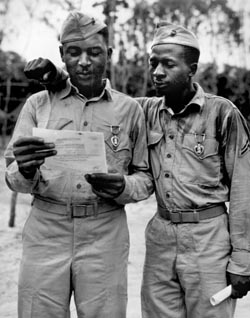

As for the rest of his tenure on Iwo Jima, McPhatter saw white Marines willing to provide their own blood directly, via blood transfusion, to wounded Japanese prisoners, while no one ever asked an African American to give blood—either to white or Japanese wounded. McPhatter was also perturbed that almost every time a combat photographer wandered by he turned his camera away from the black units, sharing their blood and sweat with their white comrades, and blatantly refusing to film their activities. Only a few shots exist of black Marines on Iwo Jima.

After the war, McPhatter became a Navy chaplain and served during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, retiring with the rank of captain. He died in 2009.

The last land campaign of the Pacific War for these Marines was the invasion of the 466-square-mile island of Okinawa on April 1, 1945. Okinawa became Japan’s final death match, where the largest collection of African American Marines and sailors saw their last battle of the war.

From the Corps came the 1st, 3rd, and 12th Ammunition Companies. The 5th, 9th, 10th, 18th, 37th, and 38th Depot Companies began arriving on May 21, 1945. In a futile, desperate attempt to throw back the invaders, over half a dozen Japanese “Betty” bombers flew over Yontan Airfield on May 24, 1945. It seemed each plane carried at least 78 banzai-crazed Japanese looking to land in the midst of an American airstrip and destroy the planes. Most were shot out of the sky. One or two flew off and were unaccounted for. One plane made a wheels-down landing on the strip.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, the 10th Depot Company never shirked their military duty as an airstrip security force. In a major standoff, the Japanese got as far as destroying eight planes, damaging 24 others, and burning up 70,000 gallons of aviation fuel before being stopped by the 10th Depot Company; 69 dead Japanese were collected across the airstrip.

Fighting in the Pacific came to an official end on August 14, when the Japanese agreed to unconditional surrender following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the official surrender documents were signed aboard the battleship USS Missouri on September 2, 1945.

Although they had been segregated, abused, disrespected, discriminated against, and used as common laborers because they were thought to be incapable of combat, the black Marines proved otherwise. They had broken the longstanding military color barrier, and life in the Marine Corps—and throughout the rest of the U.S. armed forces—would never be the same. African American soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen would distinguish themselves in all of America’s upcoming wars.

Although there were no black Marines in the two groups that hoisted the flags above Iwo Jima, their fingerprints were on the pole used to fly the first flag. And they will always be there.