By Mark Carlson

The night of July 29, 1945, was dark and clear over the Philippine Sea. A gibbous moon hung almost directly overhead, just a few days past full, casting its pale gray light over the dark waves. Thirty feet under the surface the black hull of a Japanese submarine moved slowly northward, its presence betrayed only by the shaft of a periscope cutting across the water. Just visible on the northern horizon, a huge darkened ship raced closer, unaware of the deadly predator in its path.

At 0003 hours the silent night air was rent by two roaring explosions and towering columns of white water erupting from the side of the doomed ship. Two 1,200-pound warheads had turned heavy armored steel into twisted rents and shredded bulkheads. Great spires of yellow and orange flame burst out of the ship, illuminating the sea for 1,000 yards. Entire compartments were shredded, killing and wounding hundreds of sailors who had taken their mattresses on deck to escape the humid spaces below.

The heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis leaned far to starboard as hundreds of tons of seawater entered the torn hull.

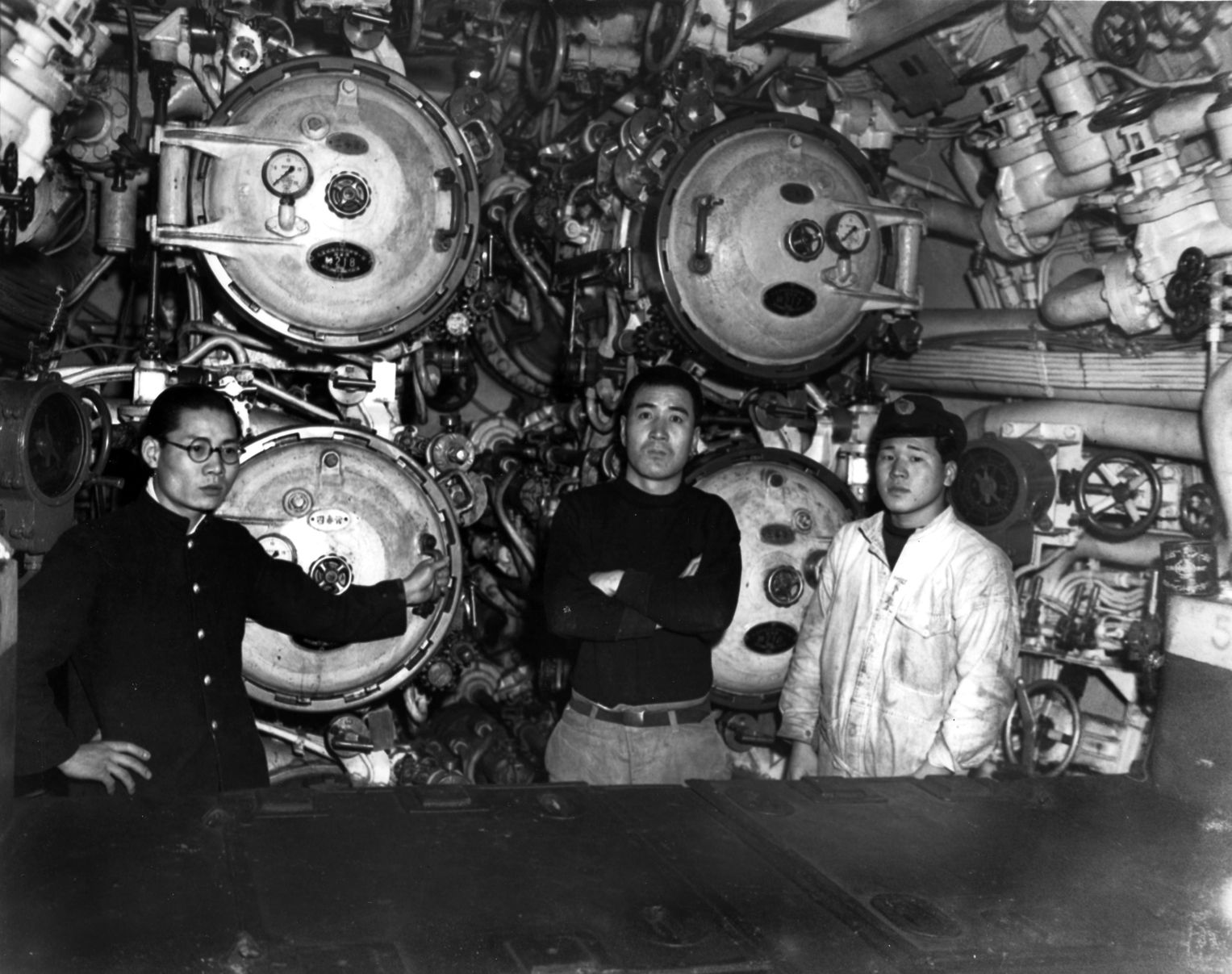

With his eye to the submarine’s periscope, Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto watched as the big American cruiser began to sink even as her powerful engines drove the hull forward past the boiling cauldron of roiled water caused by the torpedo hit.

He had known he would have only one chance. Watching the cruiser coming closer in the reflected glare of moonlight, he had ordered all six tubes ready. Midnight turned the date to July 30 as his crew awaited the order to fire.

Two minutes later, six Type 95 wakeless torpedoes shot out of the submarine’s bow tubes at three-second intervals. The torpedoes were angled to fan out and cover the greatest area. With their contra-rotating propellors churning the black waters 12 feet under the surface, the torpedoes reached their maximum speed of nearly 46 knots. Hashimoto, never taking his eye off the night periscope, counted off the 50 seconds it took for his fish to reach the ship. When the sounds of two detonations resounded through the hull, the crew of I-58 cheered. Hashimoto smiled as he watched the huge ship sink, leaving a wide swath of roiled water, burning oil and swimming sailors in its wake.

His Imperial Japanese Majesty’s submarine I-58 had just made its first and most important kill of the entire Pacific War. The attack had lasted only 27 minutes, but it had taken the better part of four years for the I-58 to write its name in naval history.

Mochitsura Hashimoto was born in Kyoto in 1909 to a Shinto priest and his wife. From the start he had his eyes on a naval career over his father’s wishes. Short, stocky and bandy-legged, Hashimoto had the right build for the navy. He had intelligent, wide eyes and radiated confidence. He joined the navy in 1927 and attended the Imperial Naval Academy at Eta Jima at the entrance to Hiroshima Bay. He received his commission in 1931. His first three years were spent on destroyers and submarine chasers. In a way this gave Hashimoto an advantage. He learned how submarines were hunted, using the early sonar and ASW tactics of the 1930s. He was promoted to lieutenant on December 1, 1937, while serving aboard a gunboat off the Chinese coast.

He realized his dream of being a submariner in May 1939, when he began a six-month torpedo training course at Yokosuka Naval District. He began submarine training, graduating and being assigned as torpedo officer aboard the I-155 in October 1940.

Tensions between the United States and Japan had been increasing and war seemed nearly inevitable. The Imperial Navy began an intensive training and building program.

Hashimoto, whose calm and efficient work brought him to the attention of officers in the navy, was assigned to the new submarine I-24, becoming torpedo officer on October 31, 1941. The war clouds were looming ever closer. The I-24’s captain was Lieutenant Commander Hiroshi Hanabusa. His and four other I-class boats were each going to be modified to carry a single midget submarine. No target was named, but it was obvious to the sub’s officers that the target was likely to be the United States Navy.

Moored at the huge naval base at Kure on the Inland Sea, I-24 and her four consorts trained with the midget submarines.

On November 18, they left Kure and entered the Bungo Strait between Kyushu and Shikoku. Heading east, the officers and crew were told they would be launching their midget sub to attack the American navy base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

On the night of December 6, the I-24 was 10 miles off the southern coast of Oahu, within sight of the lights of Waikiki. Between 1215 and 0333 hours the five submarines surfaced and launched their Ko-hyoteki “Scaly Dragon” Type A midget submarines. At 78 feet long they carried two type 93 torpedoes and a crew of two. The I-24’s midget, Number 19, was piloted by Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki and Petty Officer Kiyoshi Inagaki. All hands waited out the long morning as the air attack bombed Pearl Harbor. But nothing was heard of the midget sub. None of the five subs managed to inflict any damage. Due to a faulty gyrocompass, Sakamaki’s sub became hopelessly lost and grounded on the eastern shore of the island. He became the first Japanese POW of the war. Inagaki drowned.

Returning to Kure a few days later, the sub waited for new orders. In February 1942, Hashimoto was reassigned to the advance submarine course and graduated in June, just after the defeat at Midway. But instead of being given his own boat, Hashimoto spent the next 27 months commanding Submarine Squadron 31 to train new crews in submarine doctrine, tactics and testing new equipment.

Japan had started the war with about 60 submarines ranging from older, slower and smaller prewar designs to the fast new ocean-cruising I-class that would dominate the navy. Despite possessing some of the most advanced subs in the world, the navy had yet to learn how to best use their big underwater predators. The Naval General Staff considered the submarines as secondary to the battle fleet. The surface force, with its big guns, was still considered the most important element of naval warfare. Even after aircraft carriers eclipsed the battleships, the long-held belief that big ships and big guns would decide the fate of battles and wars persisted. Submarines were to patrol ahead of the surface fleet, scouting for enemy ships. They would prowl among the combatants like dogs at a picnic, attacking enemy ships and picking off stragglers. There was little thought given to using subs as the German Navy had done in the First World War, and were still doing in the Atlantic. The sinking of the American carriers Yorktown and Wasp, and the damaging of the battleship North Carolina was all the proof the high command needed that they were right.

The war turned against Japan in the summer of 1943. Even then the Naval General Staff refused to consider sending subs to the ever more crowded sea lanes between America and the Pacific. Thousands of Liberty Ships carried vital war supplies, planes, troops, tanks, fuel, food and ammunition to the war zone. Except for escorts, these ships were vulnerable and exposed. Still the ancient code of Bushido dominated. They ordered that all submarines seek out only enemy warships, the bigger the better. Sub commanders were ordered to ignore, even in cases of extreme advantage, any unarmed transports. But with transports outnumbering combatants by 20 to one, it was folly to waste the limited number of subs and crews for such a thin probability of success.

By early 1944, Hashimoto could justifiably be considered one of the best and most skilled submarine officers in the Imperial Navy. His specialty, other than torpedoes, was the development of underwater sound technology. Early in 1944, he had managed to send a sound transmission more than 300 miles, a feat that was as yet impossible even for the United States. Hashimoto had learned all the tricks of the trade, especially at attack and staying alive in enemy waters. Cautious and clever, he possessed the one skill most needed: patience. He constantly drilled his crews in the art of being silent in the deep, listening with all their senses as the water pressure stressed the hull and sweat beaded on every face and surface. Those were the times submariners realized their vulnerability, when the thrumming noise of a patrol boat passed overhead, when the air grew foul and hot. Yet Hashimoto taught his men how to hunt and live by depending on each other and the submarine.

While he did not yet know it, his future command, the new I-58 had been built and launched at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal in June 1943. Five months later Hashimoto was promoted to lieutenant commander. In May 1944, having had more than his fill of training duty, Hashimoto received orders to proceed to Yokosuka to take over the new submarine. His first view of the new boat was both awesome and intimidating. Sleek and jet-black, the boat rested at its slip like a huge shark.

The Type B3 submarine displaced 2,200 tons, half again as much as the new Balao-class American subs. At 350 feet long and with two Kampon diesel engines producing 4,700 horsepower, I-58 could cruise 21,000 miles at 17 knots on the surface and 12 submerged, a very respectable speed for such a large boat. Hashimoto commanded a crew of 107 officers and enlisted men, many of whom he chose from other subs he had commanded.

One of the most revealing characteristics of Japanese submarines was the arrangement of torpedo tubes. Unlike German, American, and British subs, which had bow and stern torpedo tubes, the I-class vessels had six tubes in the bow and none at the stern. Japan’s submarines were expected to be on the attack, never in retreat. In western navies, the logical addition of stern tubes made it possible to make an approach and attack with the bow tubes, and while they were being reloaded, make another attack with the stern tubes.

The I-class boats carried 19 Type 95 torpedoes, the fastest in use by any navy in World War II. The Type 95 was second only to the famous Type 93 Long Lance used by surface ships. The Type 95 could run for 12,000 yards at nearly 56 knots. The warhead weighed 1,200 pounds, giving it considerably more punch than the American Mark 14 and Mark 16 torpedoes.

Even before being launched, I-58 was configured for a role that gave her new captain mixed feelings. In addition to a cylindrical hangar and catapult to launch a floatplane, shackles for four Type 1 Kaiten human torpedoes were welded to the sub’s deck aft of the conning tower. The Kaitens had first been proposed in 1943, and later given top priority as a means of turning the war in Japan’s favor. Kaiten translated as “Turn the Heavens,” an indicator of how confident the high command was in the concept. Using a modified Type 93 Long Lance torpedo, Kaitens were fitted with a pilot’s compartment that permitted him to use the motors and control surfaces to leave the mother sub and steer to an enemy warship. The pilot literally sat inside the 36-inch diameter torpedo body. The pilots were well aware they were intended to die in the attack. The Kaitens had an astonishing range of nearly 40 miles at more than 20 knots, but this was impractical. The oxygen was only good for about half an hour. It was intended for the mother sub to move in as close as possible to an enemy anchorage at night to release the Kaitens. Poor visibility and rudimentary instruments made it very difficult for a Kaiten to be used against a moving ship.

Hashimoto, by training and experience, preferred conventional torpedoes. But his new sub was going to carry the Kaitens to enter enemy fleet anchorages and sink the ships. The first use of the Kaiten was in November 1944, at Ulithi in the Carolines. The I-47, loaded with four of the new weapons, moved close to the entrance to the lagoon. I-47’s captain looked through the periscope and saw a large cruiser, some battleships, and beyond them, carriers. He ordered the sub surfaced in the dark. The Kaiten pilots climbed into their torpedoes and moved off. When explosions were heard, the crew cheered. The approach of destroyers forced I-47 to leave the area. Radio Tokyo reported a great victory, with several American warships sunk at Ulithi. A tanker filled with aviation fuel was sunk, but that was all.

Hashimoto was frustrated with how the Naval General Staff was using its dwindling fleet of subs. Even those who rode bicycles to save gas refused to see how sinking American tankers and transports would cripple the enemy war effort. They still insisted on the grand gesture of sinking capital warships. They believed wholeheartedly in the Kaiten.

In December, the new I-58 and her crew were assigned to Submarine Division 15 and its special unit, the Kongo Diamond Group, with five other I-class boats.

The next Kaiten strike was to use six groups of subs to simultaneously hit five American anchorages. After a week of training in the Inland Sea, I-58 refueled and provisioned for its first patrol on the last day of 1944. Hashimoto’s target was Apra Harbor in Guam. Accompanied by I-36, I-58 was carrying four Kaitens and their eager pilots. After two days of careful maneuvering, during which several unarmed transports passed by unmolested, I-58 slipped past the outer reef.

In the predawn of January 12, Hashimoto surfaced and the four Kaitens headed to the harbor mouth. Three went on their way, but the fourth human torpedo exploded just after being launched. After diving, I-58’s crew waited while the hydrophone officer listened. A distant underwater explosion was heard, and Hashimoto risked raising the periscope to look. He saw two columns of smoke rising on the dawn horizon. Apparently at least two of the Kaiten pilots had been successful in sinking enemy ships.

With no more Kaitens aboard Hashimoto ordered I-58 back to Kure, where he reported success. He and his crew were credited with sinking an escort carrier and a large tanker. This seemed to confirm the Naval General Staff’s delusion of the triumph of the Kaiten program. In fact, I-58’s Kaitens had sunk not a single American ship.

Kaitens had been credited with at least 60 sinkings. The problem, as Hashimoto could have explained had the high command been willing to listen to a lowly lieutenant commander, was that there was no way for a mother submarine to watch and assess the true results of a mission. The actual statistics were far different than what the navy believed. Only three U.S. ships were sunk for a loss of 106 Kaiten pilots and their craft. The U. S. Navy was aware of the new menace and was on the alert around its bases and fleets. Several of the Kaiten mother subs were sunk without being able to attack.

On March 1, I-58 accompanied I-36 to attack the fleet at Iwo Jima, but the operation was cancelled on March 7. Ordered to head for Ulithi, the sub had to jettison two Kaitens for greater speed. But instead of participating in the Kaiten attack, she was to act as a radio link for 24 twin-engine Francis kamikaze planes. After being savaged by American fighters, only six reached Ulithi. One managed to cause serious flight deck damage to the carrier USS Randolph. None of the Kaitens were able to enter the anchorage.

The I-58 had a role in Operation Heaven One, the suicide dash of the super battleship Yamato and nine escorts to attack the Allied invasion force at Okinawa. Leaving Kure on April 4, 1945, I-58 headed south, constantly hounded by American patrol planes. Even surfacing at night with the primitive Type 22 air search radar was dangerous. At most they could get 10 minutes of the four hours needed to recharge the batteries before Hashimoto’s lookouts spotted approaching planes. Frustration mounted.

On April 6, Hashimoto was unable to fix his position to less than 50 miles north of Okinawa. There was virtually no chance of getting close to the U.S. Fifth Fleet under those conditions. Hashimoto finally broke off and headed west toward the Chinese coast, where he surfaced and made his report. Yamato and most of her consorts were sunk less than 70 miles from Kyushu, the ultimate kamikazes. Ordered to return to Japan, I-58 had to evade over 50 air attacks during the three weeks it took to reach base.

While I-58 had been at Okinawa, the heavy cruiser Indianapolis was attacked and bombed by a Nakajima Oscar kamikaze. The armor-piercing bomb tore down into the crew spaces and through the fuel tanks and hull, finally exploding in the water under the ship.

After hasty patching, the ship was sent to Mare Island in California for major repairs. Captains Charles McVay and Hashimoto passed within 100 miles of one another. But their destinies lay more than three months in the future.

Back in Kure by April 30, I-58’s never-used aircraft catapult and cylindrical hangar were removed and two more Kaiten shackles fitted. Still the high command only saw Kaiten stars in their eyes. During this time a B-29 bombing raid hit Kure. Hashimoto’s sub was not hit, but it only reinforced his opinion that the end for Japan was near. By July 1945, the Imperial Navy was down to fewer than a dozen submarines capable of patrolling the Pacific.

Submarine I-58 had not managed to sink a single ship. Frustrated but still hungry to serve his emperor, Hashimoto, now 36, read over his orders for the next patrol. He was to take his boat through the extensive minefields around Kyushu on July 18 and head south for the Philippine Sea. Located between the Marianas and Leyte, and between Palau and Okinawa, it was called the Crossroads of the Pacific. The rear area had many transports and warships transiting north and south, east and west. It was an excellent hunting ground, even if the weapon was the useless Kaiten. But I-58 still carried 19 Type 95 torpedoes.

The first targets he encountered were a tanker and destroyer on the afternoon of July 28. Seeing the eager Kaiten pilots, Hashimoto chose to let them try. At 1431 and 1443 hours, two Kaitens sped off with their exultant pilots. Nothing happened until almost 1530 hours when two explosions were heard. But rain squalls made seeing anything impossible. They had attacked the tanker SS Wild Hunter and escorting destroyer USS Arthur Harris. Unsure of what happened, Hashimoto went in search of more targets. Wild Hunter had seen the Kaiten’s periscopes and opened fire with its 4-inch gun. The Harris moved in and dropped depth charges. Neither ship was hit. The explosions were probably from the Kaiten pilots fulfilling their orders to self-destruct.

At 2330 hours on July 29, I-58 was cruising submerged west at two knots while the crew tried to get some rest. The boat was hot and humid as Hashimoto visited the Shinto Shrine and took his watch. He raised the big night periscope and took a careful look around the moonlit sea. At 2332 hours I-58 surfaced. On the dripping bridge Hashimoto and his assistant navigation officer, Lieutenant Tanaka, scanned the horizon. Suddenly Tanaka said, “Enemy ship, bearing red, 90 degrees!” Hashimoto turned left and raised his big binoculars. There it was, a large ship, probably a warship, coming at them from the north, about five miles away. The ship was silhouetted by the moon.

“Dive, dive!” Hashimoto ordered as he went down the hatch behind Tanaka. “Ship in sight,” he said to the conning tower crew. “All tubes ready, Kaitens stand by.”

But Hashimoto already knew he was not about to risk losing this target to the fickle Kaitens. He would use his trusted Type 95 torpedoes. His target was the recently repaired USS Indianapolis, which had just completed a top-secret speed run from San Francisco to deliver the explosive elements of the atomic bomb to the island of Tinian in the Marianas. She was on her way to Leyte for reassignment. And no one knew she was there. Except Hashimoto.

It was 2340 hours on July 29, 1945. “Up periscope,” he said. Peering through the eyepiece, Hashimoto watched as the big black ship drew closer. It was not zig-zagging, but that would not have mattered. He was in a perfect attack position off the target’s starboard bow. He watched, and nodded to his torpedo officer. “Ready tubes, three second intervals.”

The big ship was moving at about 12 knots. Hashimoto would send his fish out when the range was 1,600 yards. He tensed. “Fire!”

The sub shuddered six times as the diving officer opened the bow buoyancy tanks to compensate for the loss of eight tons. It was done. “We’ve got her,” Hashimoto said under his breath. It was two minutes after midnight on July 30, 1945.

Ironically, I-58’s one major victory was accomplished not with the vaunted Kaiten, the overriding obsession of the Naval General Staff, but with conventional torpedoes, just as Hashimoto had been advocating from the start. Returning to Japan he heard of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not knowing how close he had come to missing Indianapolis before she delivered her deadly cargo at Tinian. But history is replete with such missed opportunities.

Mark Carlson has written on numerous topics related to World War II and the history of aviation. He resides in San Diego, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments