By Eric Niderost

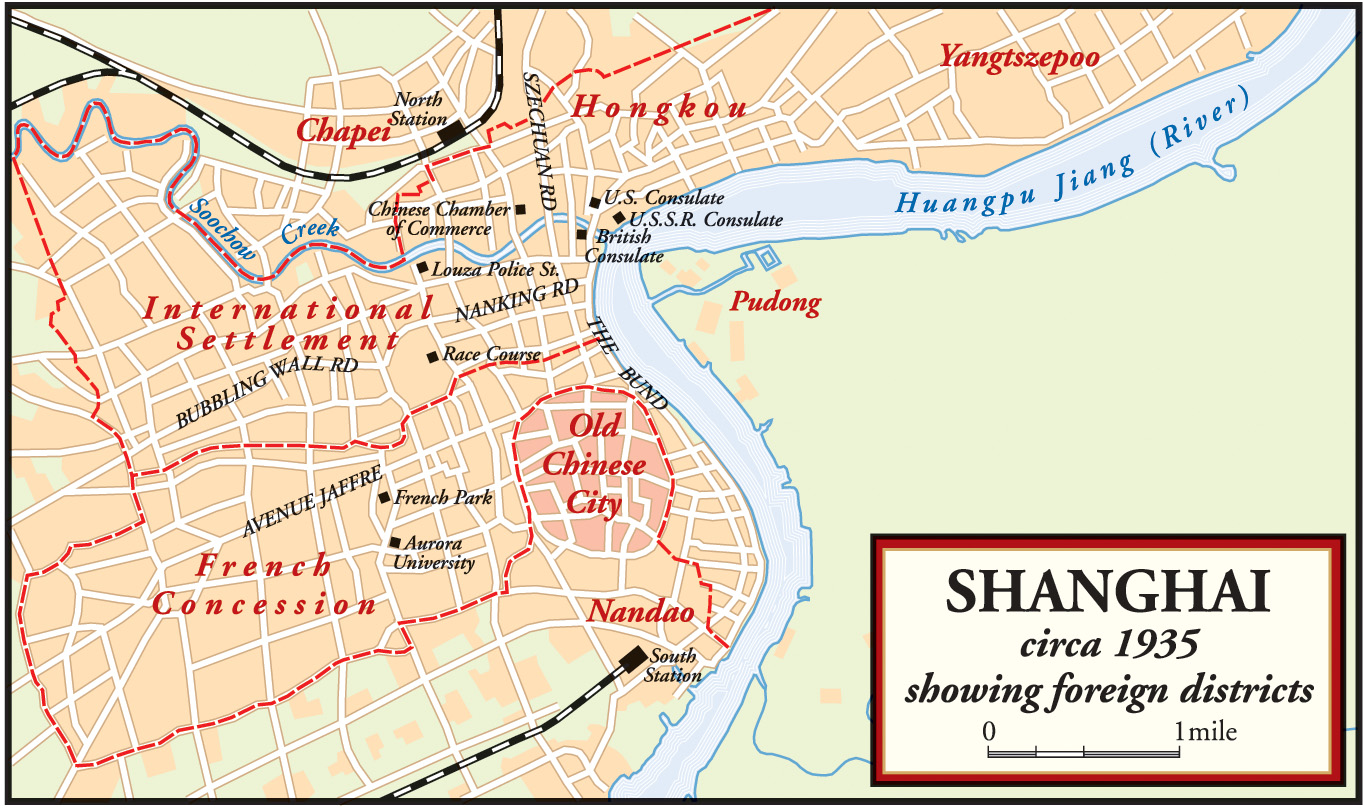

In the 1930s Shanghai was in its heyday, a teeming metropolis of some 3.5 million people. The great city was a fascinating blend of cultures, its very existence refuting Rudyard Kipling’s famous aphorism. Here, on the lazily snaking banks of the Huangpu River, East and West did meet. The river was literally an artery of commerce, pumping trade into the city’s vibrant commercial heart.

China Forced To Open Trade Relations

Shanghai was a bastion of Western capitalism, business its life blood. British and American Tai-pans (heads of business firms) might attend church on Sunday, but on weekdays Mammon, not God, was Shanghai’s principal deity. The city was one of the original “Treaty Ports” opened up by the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. China had just been disastrously defeated in the so-called “Opium War” and had to bow to British demands. Largely self-sufficient, despising foreigners as “outer barbarians,” China had to be forced to establish normal diplomatic and trade relations with the outside world. The British took the lead, but the United States, France, Japan, and a host of other countries were quick to follow.

Beset by foreign encroachments from without and internal rebellion from within, China was in turmoil throughout much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Seeking China’s trade, yet wanting to distance themselves from its social and political troubles, treaty powers established the principle of “extraterritoriality” which the Chinese naturally resented. Foreign enclaves would be set apart, largely self-governing and above all not subject to Chinese law.

Shanghai’s International Settlement and French Concession were outgrowths of these developments. Although physically connected to the Chinese-ruled greater Shanghai, the International Settlement was a largely self-governing territory administered by the Shanghai Municipal Council, which was dominated by foreign business interests, largely British, though other powers such as the United States had seats. The International Settlement had been formed by uniting the British and American enclaves in 1863. The French Concession, ruled from Paris, was a separate entity.

The Bund—the word is derived from an Anglo-Indian word meaning “quay” or embankment—was the International Settlement’s grand showplace, an imposing row of banks, hotels, and office buildings that stretched for a mile along a bend of the river. To the visitor, the buildings were exotic outgrowths, massive symbols of Europe and America that were somehow magically transplanted to Chinese soil. The Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, the Yokohama Specie Bank, the exclusive Shanghai Club, and the Cathay Hotel—these were powerful institutions whose soaring domes and stately columns were outward symbols of inner wealth.

The Bund’s grand boulevard was crowded day and night, an ever-changing spectacle that revealed both the best and the worst of humanity. Gawking tourists rubbed elbows with swaggering off-duty sailors, White Russian refugees, British businessmen, and petty criminals. Rickshaw men pulled beautiful Chinese women dressed in silk qi paos, and red-turbaned Sikh policemen kept a wary eye out for trouble. And above all there was noise—autos honking, ship whistles blowing, swarming Chinese rickshaw men crying for fares—an ear-splitting cacophony of commerce.

The International Settlement and neighboring French Concession were artificial creations, safe harbors from the turbulent social and political storms that plagued China. Events were to prove this safety was more an apparition than reality. In the 1930s there were around 60,000 foreigners in the International Settlement and French Concession. They were vastly outnumbered by the million or so Chinese who also lived there.

Strong Japanese Presence In Shanghai

The Japanese also had a strong presence in Shanghai, a presence second only to the British. Japan was a modern nation whose rapid industrialization in the 19th century had amazed the world. Most Europeans and Americans looked on the Japanese as “honorary” Westerners whose accomplishments and growing military power won a grudging admiration.

But Japan’s Westernization was in some respects superficial. Beneath the modern, progressive veneer, some of the more disturbing aspects of Japanese culture still existed and threatened to break to the surface. The Bushido code, or “way of the warrior,” exalted military virtue, dedication to the emperor, and an almost fanatical contempt for death. Japan’s celebrated samurai warriors had practiced Bushido in one form or another for centuries, but in the 1920s and 1930s the world saw its modern reincarnation.

Japan’s population had grown from about 30 million in 1868 to about 65 million in 1930. Japanese farmers were hard-pressed to feed this expanding population, and some argued territorial expansion was the only solution. Of course, aggressive Japanese imperialism was an old story. In 1910 Japan had annexed Korea, beginning a nightmare of cultural suppression, economic exploitation, and political terror on the long-suffering peninsula. But Korea was Japan’s foothold on the Asian mainland, springboard to a greater prize—China.

In the 1920s and early 1930s Japan became infected with nationalism and militarism. When combined with the samurai traditions and the Bushido code, this militarism and ultranationalism produced a particularly virulent brand of imperialism. The worldwide economic depression of the 1930s hit Japan hard, making imperial and foreign conquest seem a viable solution to the island nation’s troubles.

In 1931, the “Manchurian Incident” began a whole new round of Japanese aggression. Manchuria was the northern province of China, and Japan maintained a garrison there, Kwantung Army, to protect Japanese property and economic interests. Officers in the Kwantung Army needed a pretext to conquer Manchuria, so they created one. They blew up a portion of a Japanese-owned Manchurian railway and blamed the destruction on the Chinese. It was a transparent deception, but provided the excuse the Japanese Army needed. In due course Manchuria was invaded, weak Chinese armies routed, and a puppet state called “Manchukuo” established.

Japanese Provocation Ignites Passions In Shanghai

The Manchurian Incident sparked condemnation from around the world, particularly the United States, but most countries were more concerned with the Depression than with far-off China. Pu Yi, the last emperor of China, was duly installed as ruler of an “independent” Manchukuo, but his tinsel regime was nothing more than clumsy window dressing. Japan’s naked aggression provoked a storm of protest all over China, but nowhere was the patriotic furor greater than in Shanghai.

Chinese demonstrators crowded the streets, angrily shouting anti-Japanese slogans, and posters were tacked up that denounced Japanese imperialism or simply urged Chinese citizens to “Kill All Japanese.” Soon talk was transformed into action, and the city’s Chinese business community organized an effective boycott of all Japanese goods. All Japanese products, even innocuous toys and bicycles, disappeared from Chinese store shelves. Goods piled up in Japanese warehouses because no Chinese businessman would accept Japanese products.

The Japanese were an important part of the International Settlement’s foreign community. A small waterway called Soochow (now Suzhou) Creek meandered through Shanghai, a watery finger that formed a boundary between the International Settlement and the Chinese-controlled Greater Shanghai before turning sharply and dividing the settlement itself into two distinct halves. Soochow Creek was spanned by the Garden Bridge (now Waibaidu Bridge) near where it emptied into the Huangpu River.

A traveler crossing the Garden Bridge from the Bund would find himself in the International Settlement’s Hongkew District. Hongkew was the Japanese section of the settlement, boasting a population of 30,000 Japanese residents. Numerous shops, bars, and even Geisha houses gave the area its local name of “Little Tokyo.” Hongkew was a natural target for Chinese patriotism. Normally, Japanese imports comprised 29 percent of Shanghai’s yearly total. Once the boycott took effect, that figure plummeted to 3 percent. Seven hundred tons of unsold Japanese goods gathered dust on Hongkew’s piers and godowns (local term for warehouses).

Japanese shops in Hongkew were forced to close, and Japanese residents boarded ships to return to the Home Islands. They had little alternative. Chinese merchants would not even sell them food. These events played into the hands of the Japanese military, which was encouraged by the relative ease of its Manchurian conquest.

Unpaid Chinese Troops Pose Greater Threat Than Japanese

Chapei was a Shanghai district to the north of Hongkew, just beyond the boundary of the International Settlement. It was a heavily industrialized area and home to thousands of impoverished Chinese workers. Streets were lined with dingy, red-brick buildings and grimy factories. The Commercial Press, a Chinese-owned publishing house in Chapei, was a huge concern that supplied three out of every four school textbooks in China.

The situation was becoming more and more volatile, and tensions were not eased when the 31,000-man Chinese Nineteenth Route Army under the command of General Cai Tingkai arrived. The majority of these troops were southerners, Cantonese speakers from Guangdong, and only nominally under the control of Chiang Kai-shek’s national government. General Cai paid lip service to the national government, but few doubted who was really in command.

The Nineteenth Route Army had not been paid in some time, which sent shivers of fear coursing down the backs of many foreigners residing in the settlement. General Cai might turn warlord and replenish his coffers by sacking the International Settlement. Ironically, the Chinese, not the Japanese, were considered the greater threat by the Western powers at this stage. To defuse the situation, funds were to be raised to pay the soldiers.

Japanese Send In Monks To Stir Up Trouble

Deliberately seeking to provoke an incident, the Japanese sent five members of the Buddhist Nichiren sect into Shanghai. The Nichiren sect was ultranationalist, believing it was Japan’s divine mission to rule Asia.

On January 18, 1932, the Japanese Buddhist monks paraded through Chapei, according to some accounts loudly chanting anti-Chinese slogans. It was a deliberate provocation, and the Chinese were quick to respond with violence. One monk was killed and two others wounded. In retaliation, a Japanese mob set San Yu Towel Company on fire, and two Chinese died in the conflagration.

They had played right into the hands of the Japanese. The Japanese consul general presented Shanghai Mayor Wu Tiecheng with a series of demands, including the arrest of those responsible for the monk’s death, an immediate suppression of all anti-Japanese organizations, and an end to the boycott within 10 days. Mayor Wu consulted with the central government in Nanking (Nanjing), but ultimately the decision would be his. While the mayor deliberated, the Japanese were busy sending naval reinforcements to Shanghai, including a cruiser and 12 destroyers from Sasebo. On Saturday, January 23, a contingent of 500 Japanese Marines landed at the Yantzepoo section of the International Settlement, the vanguard of many more troops to come.

As the crisis deepened, the International Settlement’s Defense Committee was galvanized into action. Most of the major powers had small military units in Shanghai whose primary mission was to guard the lives and property of their nationals. The Defense Committee was composed of the chairman of the Municipal Council, the commissioner of police, and various officers from the British, American, French, Japanese, and Italian military.

The Shanghai Volunteer Force, a curious multinational militia that mirrored the cosmopolitan nature of the International Settlement, was also represented. Most of these men were “weekend warriors,” Shanghai businessmen who joined partly as a civic duty and partly because they were defending their own interests. There were over 20 units in all, including the American Company, the Shanghai Scottish, the Portuguese Company, and a White Russian regiment. All were volunteers, save the Russians, who were paid a salary.

On Tuesday, January 26, Chinese authorities declared martial law and began stringing barbed wire and laying down sandbags. Events were clearly spiraling out of control, prompting the International Settlement’s Municipal Council to declare a state of emergency. The Shanghai Volunteer Corps was mobilized, as well as various foreign military units. The International Settlement was approximately 8.73 square miles (5,883 acres), while the French Concession was almost four square miles (2,525 acres). Each unit, both professional and volunteer, was assigned a place in the defensive perimeter.

Mayor Wu accepted all the terms of the Japanese ultimatum on the afternoon of January 28, even going so far as to close down the offices of the anti-Japanese boycott organization. In reality, the demands had been more of a sop to world public opinion than a real policy. Admiral Shiozawa was determined to punish the Chinese for their acts of defiance. He admitted as much to New York Times reporter Hallett Abend, when the two men met aboard the Japanese flagship, the cruiser Idzumo, which was anchored in the Huangpu.

The admiral admitted Mayor Wu’s capitulation was “beside the point,” adding, “I’m not satisfied with conditions in Chapei. At 11 o’clock tonight I’m sending my marines into Chapei to protect our nationals and preserve order.” Shiozawa tried to cultivate Abend by feeding him caviar and pouring cocktails, but the American was not fooled by this sudden hospitality.

Abend left to file his story, pausing only to warn the American Consul-General, Edwin S. Cunningham, of what he had learned. Chapei was just across the International Settlement’s border from Japanese-dominated Hongkew. Shiozawa’s target was Chapei’s North Station, where a tangle of railroad tracks filtered through a labyrinth of locomotive sheds, warehouses, and outbuildings. The Japanese admiral had utter contempt for the Chinese, predicting he would take North Station “within three hours, without firing a shot.”

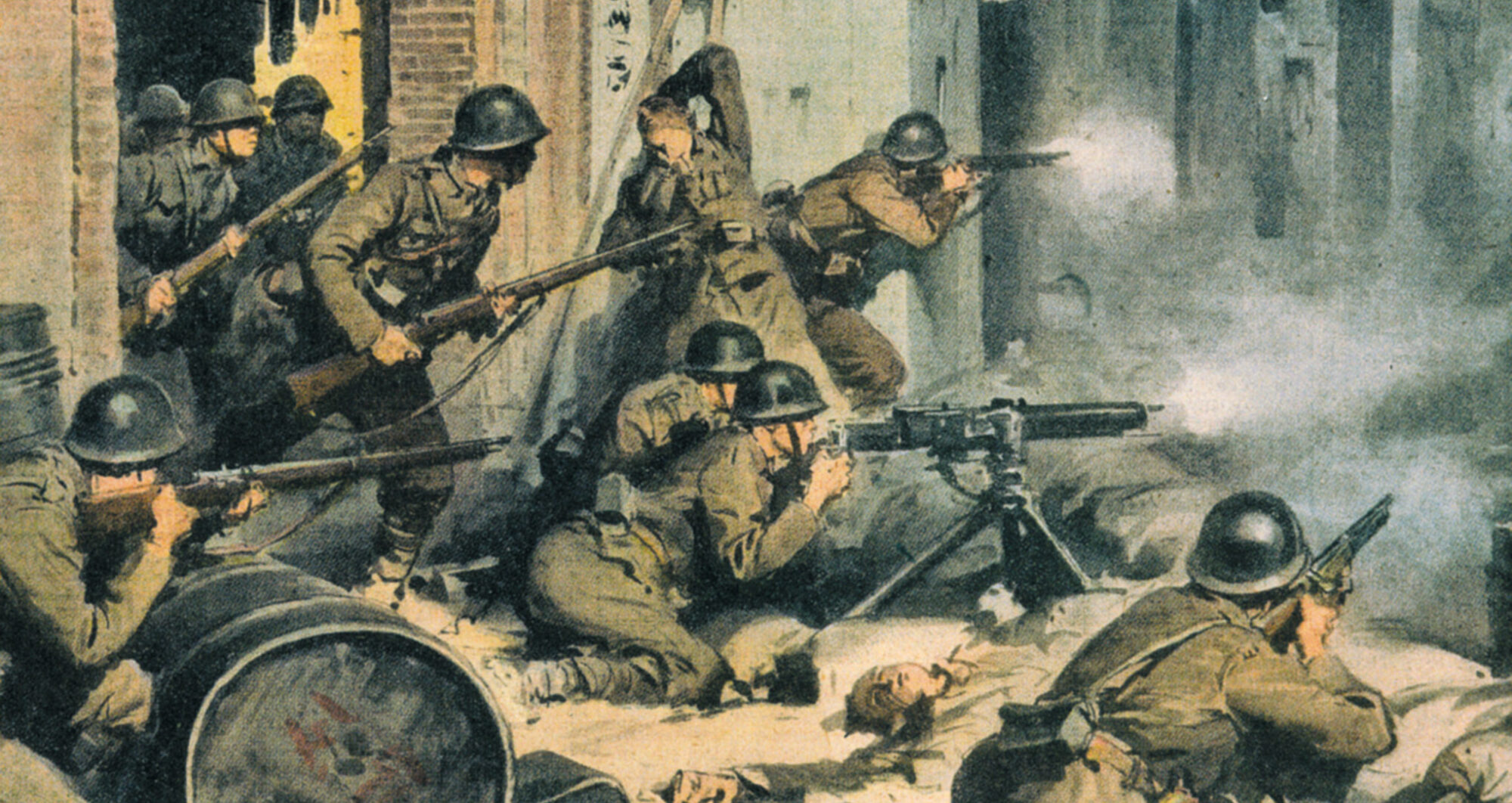

The men of the Nineteenth Route Army, some of them teenagers, awaited the Japanese onslaught. They were indifferently armed, and their dirty tennis shoes, caps, and faded cotton uniforms gave them a rag-tag appearance. But they made up in courage what they lacked in training or weaponry, and were determined to resist to the last man.

At 11 o’clock, 400 Japanese Marines of the Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) marched from their headquarters on Kaingwan Road in Hongkew and clambered into 18 trucks. Japanese civilians were on hand to cheer them on their way, filling the Marines’ ears with triumphant shouts of “Banzai!”

The Japanese Marines were driven to a point near North Station, then disembarked and sorted themselves out for the offensive. Each unit was guided by men carrying flashlights. The light beams stabbed through the darkness and also made the advancing Japanese perfect targets. About 50 yards from the station the Japanese saw a makeshift barricade of barbed wire and sandbags; any holes in the wall were plugged by an odd table or chair.

Cai Springs Trap For Japanese Marines

At that moment, Abend strained his ears, listening in the darkness for the sounds of fighting he knew must come. He was not disappointed, because the sharp crack of two rifle shots echoed through the night, followed by the staccato chatter of machine-gun fire. General Cai had sprung a trap on the unsuspecting Japanese; the whole area was swarming with Chinese snipers positioned in every building. They were crack shots, and soon many Japanese Marines lay sprawled in the street in rapidly spreading pools of blood.

As the fighting intensified, the noise of battle attracted curious foreigners from the International Settlement. They lived in a privileged world, and the International Settlement’s semi-colonial status made it a safe haven from China’s endless strife. Some foreigners may have sympathized with China, but many British and American businessmen looked at Asians with a kind of bemused and cynical indifference.

As it neared midnight, foreigners came out of the settlement’s many hotels, theaters, and nightclubs to “watch the fun.” Many were in evening clothes, laughing and chatting as they ate sandwiches or gulped hot coffee to ward off the evening chill. Throngs of foreigners watched the battle from North Szechueh Road, acting as if the fighting was a sporting event staged for their benefit. Bullets whizzed nearby, and some Japanese Marines were setting up defensive positions just across the street from the curious onlookers.

Frustrated at the delays, and fearing a loss of face, the Japanese resorted to heavy-handed measures. As the weeks passed, Japanese heavy artillery pounded Chapei, the shellfire complemented by salvoes from Japanese warships on the river. But above all there were the bombers, fleets of aircraft that pummeled Chapei without mercy. Cotton mills, tenements, factories, churches, all were reduced to smoldering rubble. Foreign journalists were aghast at the indiscriminate bombing of civilians. Flames sent thick coils of black smoke into the sky, and at night the conflagration turned Chapei into an incandescent hell.

Japanese Show No Mercy To Chapei

An estimated 85 percent of Chapei was razed to the ground. Nothing was spared; even the famed Commercial Press was gutted, its many books reduced to ashes. Thousands of Chinese civilians were killed or horribly wounded, some maimed for life. Over 600,000 Chinese refugees poured into the International Settlement, an endless stream of victims carrying what little remained of their earthly possessions.

Cai and the hard-pressed Nineteenth Route Army refused to yield, though casualties were heavy. The heroic stand made headlines around the world and made General Cai an international celebrity. The Chinese community in the Philippines contributed thousands of dollars to General Cai, and in San Francisco there were fund-raising dinners.

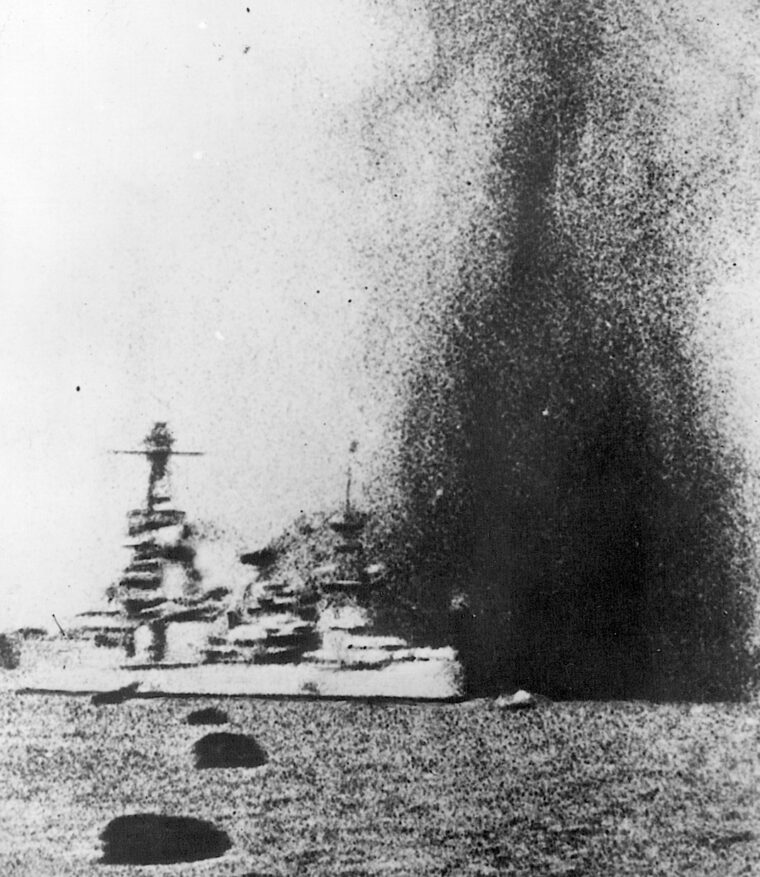

For the Japanese, it was a public relations disaster. Clumsy attempts at damage control only made it worse. Admiral Shiozawa hosted a cocktail party for the foreign press aboard his flagship Idzumo, where he noted that American newspapers had labeled him a “baby killer.” The admiral petulantly reminded Abend, ”I used only 30-pound bombs, and if I had chosen to do so I might have used the 500-pound variety.”

The Nineteenth Route Army had won a moral if not physical victory against impossible odds, but at last flesh and blood could stand no more. General Cai now had 16,000 effectives, down from the original 31,000. The arrival of 8,000 more Japanese reinforcements signaled the beginning of the end. On March 8, 1932, Japanese soldiers raised their distinctive rising sun flag over what remained of North Station. Buildings were blackened shells, and corpses were everywhere. Despite the exuberant “Banzai!” shouts, it was a hollow triumph.

Negotiations opened and dragged on for weeks. A cease-fire pact was settled with a demilitarization scheme that required Japan to remove all troops from Shanghai save its normal garrison. The Chinese were also required to withdraw and keep troops from entering a 30-mile zone around the city.

The battered Nineteenth Route Army withdrew, but its stand had humiliated the Japanese high command and boosted Chinese morale. Peace was restored, and for the next five years Shanghai returned to its magnificent, gilded decadence. Business boomed, ships steamed up the Huangpo, and the Bund was crowded by more people than ever.

General Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist Chinese leader, had offered no help to the Nineteenth Route Army during its weeks of struggle. Chiang had little love for the Japanese, considering them a “disease of the skin,” whereas the Communists under Mao Zedong were a “disease of the body.” He was basically hoarding his best divisions for his continuing campaign against the Communists.

The general had a change of heart when he was kidnapped by a warlord, who demanded he form a united anti-Japanese front against the common enemy. Chastened, Chiang agreed, and was released. This “united front” was formed in the very nick of time, because in the summer of 1937 the Japanese were on the move again. On July 7, 1937 (“Double Seven”), a missing Japanese soldier in Peking (now Beijing) formed a sufficient pretext for war. Accusing the Chinese of kidnapping him (he was supposedly later found in a brothel, sheepish but unharmed), the Japanese poured thousands of troops into North China. Peking soon fell, as did the port city of Tientsin (Tianjin).

Chiang Kai-shek knew the Chinese had little chance of opposing a determined Japanese offensive in the north. The Yangtze Valley was a different matter. Shanghai was China’s window on the world, its international showplace, and home to the largest foreign press corps east of Suez. The Chinese would challenge the Japanese at Shanghai, and in giving the Western powers a “ringside seat” in the contest, they hoped to create enough sympathy to provoke intervention.

Chinese Send German-Trained Elite Troops To Fight Japanese

Sensing trouble, the Japanese began sending reinforcements to Shanghai, at the same time evacuating their civilian nationals. The initial Japanese commitment was around 1,300 Marines of the Special Naval Landing Force. Chiang threw down the gauntlet by sending his best troops to Shanghai, the German-trained 87th and 88th Divisions. These were elite formations, tough and well equipped, and they were determined to give the Japanese invaders the fight of their lives.

On August 9, Sublieutenant Isao Ohyama of the SNLF got into a car that quickly sped along Monument Road—his alleged mission, to “inspect” the Chinese Hungjiao Aerodrome. He never reached his destination. The bullet-riddled bodies of Ohyama and his driver were found later.

On Friday, August 12, the Shanghai Volunteer Corps was mobilized and took its defensive positions along the International Settlement perimeter. The volunteers were more cosmopolitan than ever, and included a Filipino company and a Jewish company.

B Battalion of the Volunteers, which consisted of the American, Portuguese, Filipino, and American machine-gun companies, occupied the Polytechnic Public School on Pakhoi Road. By contrast, the White Russian C Battalion manned blockhouses along Elgin Road. There was even a Chinese Company, which occupied the Cathedral Boys’ School.

Regular troops defending the International Settlement included British soldiers and sailors, the Fourth U.S. Marines, Dutch Marines, and Italian Savoyard grenadiers. The nearby French Concession was also in a defensive mode, but the French preferred to go it alone. They had their own soldiers on hand, a battalion of French-officered colonial Vietnamese troops.

The Fourth U.S. Marines occupied a section of the perimeter along Soochow Creek. It was an area where the river itself formed the boundary between the International Settlement and Chinese-ruled Greater Shanghai. On the other side of the creek was Chapei, newly rebuilt and occupied once again by Chinese troops.

Sporadic fighting broke out on August 12, triggering a mass exodus of Chinese refugees from northern Shanghai, particularly from the Chapei district. Chapei may have been rebuilt, but the searing memory of the 1932 conflagration had left deep psychological wounds, still fresh even after the passage of five years. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians sought safety in the International Settlement, first entering through Japanese-held Hongkew before going on to the Garden Bridge and the Bund.

Whole families were on the move—men, women, and children of all ages. The teeming mass of humanity formed a column 10 miles long, a tragic exodus whose main goal was the supposed haven of the settlement. But the Garden Bridge that spanned Soochow Creek had not been designed to handle such a surging hoard, and a bottleneck developed. All other entrances to the Western, non-Japanese portions of the settlement had been blocked, leaving only the Garden Bridge. Once they caught sight of their goal, the refugees began to grow restless at the prospect of this entrance being sealed off.

Horrible And Deadly Stampede

The fear of not reaching safety triggered an unreasoning panic. People fell only to be tramped by hundreds of surging feet. An American named Rhodes Farmer had the misfortune of being caught in this panicking crowd, and the memory of the ensuing horror stayed with him for years. He later recalled, “My feet were slipping … on blood and flesh … a half-dozen times I knew I was walking on the bodies of children or old people sucked under by the torrent, trampled flat by countless feet….”

Worse was to follow. The Huangpu River was crowded with military ships of many different nationalities. There was, of course, the Japanese flotilla, whose destroyers used their 4.7-inch guns on the Chinese-held docks and jetties along the shore. The Idzumo, the 9,500-ton flagship of Vice Admiral Hasegawa, was moored to the Nippon Yusen Kaisha Wharf close to the Japanese Consulate and the mouth of Soochow Creek. Idzumo was an old ship, a three-funneled relic of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, but its symbolic importance made it a prime target.

The American heavy cruiser USS Augusta had recently arrived in port, carrying Admiral Harry E. Yarnell. American neutrality made for some bizarre incidents. Even in the midst of a war, Japanese destroyers and light cruisers paused to render military honors to Augusta’s embarked admiral. American civilians were being evacuated by ship, and Augusta was there to oversee and protect the operation. Several British warships were also in Shanghai, including the Kent-class cruiser HMS Cumberland.

On Saturday morning, August 14, 1937, there were signs in the sky of an approaching typhoon. Storm warning flags were hoisted, and the residents could feel the heavy gusts that blew upward of 60 mph. Few could realize that the natural storm was going to be preceded by a man-made one of even greater intensity.

Hundreds of thousands of Chinese refugees were now jammed into the International Settlement, trying to be as normal as possible in an abnormal situation. The International Settlement authorities did what they could, and free tea and rice were distributed at the New World Amusement Center.

For foreign nationals life went on as usual. Business was conducted with the same profit-driven intensity, and the city’s decadent pleasures were just as enticing as ever. The legendary luxury of the Cathay Hotel made it a mecca for the International Settlement’s social elite. Its rooftop restaurant, redolent with the sweet scent of hyacinths, was the scene of many dances.

That same afternoon, a formation of four U.S.-built Northrop 2E attack aircraft from the Second Group of the Chinese Air Force took off from Lungwha Airfield. Their destination was Shanghai, and their target the flagship Idzumo. The planes appeared over the great city around 4:15 and lost no time in diving to the attack. The Bund was densely packed with the usual cross-section of foreign businessmen, street vendors, and beggars, leavened with new Chinese refugees.

In the first moments, the bombing had the air of a sporting event, with foreigners and Chinese alike crowding rooftops and the Bund promenade to watch the show. The first one or two misses were greeted with a chorus of cheers and boos from the assembled multitude. The cheers turned to screams of anguish when two bombs completely missed their target by about a half-mile and detonated in the International Settlement.

The first bomb pierced the roof of the Palace Hotel, collapsing its upper stories like a house of cards, while the second bomb landed on the intersection of the Bund and Nanking Road, just outside the fabled Cathay Hotel. The Cathay’s wealthy guests found that death was literally at their doorstep. Charred and mangled bodies lay everywhere, and tongues of flame leaped fiercely from wrecked cars. Motorists had been waiting for a red light to change at the time of the explosion; now each vehicle became a funeral pyre for its incinerated passengers.

The First American Casualty Of WWII

The misguided Chinese attack had also affected the foreign warships anchored in the Huangpu. A 1,300-pound bomb splashed down near the Augusta’s starboard side, showering the vessel with metal splinters. Twenty-one-year-old Seaman 1st Class Freddie Falgout of Raceland, La., was killed instantly, and about 18 sailors were wounded. A case can be made that Falgout was the first American military casualty of World War II.

One of the Chinese airplanes, by some accounts damaged by Japanese antiaircraft fire, moved northwest, as if to limp home. The pilot suddenly released his payload on the intersection of Tibet Road and Avenue Edward VII just outside the Great Amusement Center. The Bund bombing had been terrible, but it paled to insignificance when compared to the Avenue Edward VII disaster. The bomb or bombs—the number is disputed—landed right in the middle of a densely packed thoroughfare.

Eviscerated bodies of men, women, and children lay in heaps, many burned beyond recognition. There were foreigners among the largely Chinese victims. Amid the carnage, one apparent businessman was seen with both legs and part of an arm blown off. He expired before help could come. The haughty Westerners and lowly Chinese refugees had come together at last, in a kind of equality of death. The Avenue Edward VII holocaust established a record up to that time of civilians killed by a single bomb. Altogether 1,123 people were killed, and as many as a thousand wounded. If the Bund victims are added to the total, it stands at 1,956 dead and 2,426 wounded.

What had caused this terrible tragedy? Various theories were put forward, most of them plausible but hard to prove. It was said that the pilot knew his aircraft was badly shot up, so he intended to release his bombs above an empty racetrack. Some said his bomb rack was itself so damaged it caused the premature release. As for the Idzumo bombing attempt, it was said that the pilots had been trained for level bombing at 7,500 feet. The approaching typhoon had lowered the ceiling to 1,500 feet, but the pilots had failed to adjust the bomb sites for the differences. The gusting winds were also advanced as a possible cause.

Land War In China Expands

In the meantime, the land war continued and the front expanded. Shanghai remained the focal point of a battle line that stretched 70 miles and encompassed both sides of the Yangtze River. Chiang Kai-shek sent the equivalent of nine divisions against the Japanese, forcing them to respond in kind. A Shanghai Expeditionary Army under General Iwace Mitsui landed on August 23, an impressive force of two large divisions and a tank corps.

August passed, then September, and the fighting showed no sign of abating. Chinese General Chang Chih-Chung began with four reinforced divisions in the Shanghai region. By September that number had jumped to 15. Foreign journalists observed the fighting from atop the 16-floor Broadway Mansions (now Shanghai Mansions). They watched in comfort, sipping drinks from a well-stocked bar. Surfeited with gin and carnage, they repaired to their typewriters to file their stories.

On November 5, 1937, four Japanese divisions (the 6th, 16th, 18th, and 114th) made simultaneous landings near Fushon and at Cha-pu on Hangchow (Hangzhou) Bay. The dual thrusts formed a pincer movement that threatened to engulf the defenders of Shanghai. The Chinese were forced to withdraw from the great port city to avoid encirclement and annihilation. The battle for Shanghai had been costly, with some 80,000 Chinese casualties; Japanese totals reached upward of 30,000.

Fleets of Japanese bombers came over the city every day, filling the air with a rain of death. Greater Shanghai was pulverized—smashed and burned almost beyond recognition. On August 28, 1937, Shanghai’s South Station was subjected to a particularly brutal bombing. Paramount newsreel cameraman H.S. Wong photographed a burned and blackened Chinese infant sitting alone amid the ruins. The photo was one of the most poignant and enduring images of the 1930s, a symbol of China as well as a searing indictment of the horrors of war.

A rear-guard Chinese unit refused to retreat, its heroic stand evoking memories of the Nineteenth Route Army five years before. These men were not callow youths, however, but part of the elite 88th Division. There were some 411 men in this unit, quickly dubbed the “Doomed Battalion”by the watching foreign press. They barricaded the five-story-high godown owned by the Joint Savings Society.

By accident or by design, the “Doomed Battalion”chose to make its stand just across the street from the Thibet Road Bridge and the entrance to the International Settlement. The Chinese performed great acts of valor. At one point, a Chinese soldier saw 20 Japanese soldiers advance near the godown. He grabbed some hand grenades, jumped in among the startled Japanese, and pulled the pins. The Japanese peppered the godown with heavy machine-gun fire, punctuated with artillery salvoes.

Food was passed to the stubborn defenders from the International Settlement just beyond. The British tried to arrange a truce, keeping the phone lines busy between Japanese headquarters and the besieged godown. Finally the “Doomed Battalion” survivors were allowed to “surrender” to the British in the International Settlement, not the Japanese. Other Chinese units that had been trapped in Shanghai followed their example. When some isolated Chinese soldiers “surrendered” to the French in the French Concession, tears of defeat streamed down their faces.

Victorious Japanese troops soon rushed up the Yangtze River Valley, leaving a path of unprecedented destruction in their wake. In December they reached Nanking, where they committed one of the great atrocities of world history. The infamous Rape of Nanking was a hellish six-week session of wholesale rape, murder, and pillage. Thousands were tortured to death for sport, and perhaps as many as 80,000 women were brutally raped. The Sino-Japanese War continued, finally merging with World War II in 1941.

The 1932 and 1937 battles at Shanghai can be considered a dress rehearsal for the later, wider war. In a sense, the first shots of World War II were fired at the great port on the Huangpu. With the wisdom of hindsight, we can say that many events at Shanghai foreshadowed the tragedies to come. The utter destruction of Chapei in 1932 and the carnage of 1937 were copied, and even surpassed, at Rotterdam, London, Dresden, and Hiroshima.

Greetings,

Can you tell me, please, the copyright status of the colored picture showing soldiers on the attack? It’s the picture in the section entitled “American bomb go astray.” Also, what nationality are the soldiers?

Thanks in advance for your help.

Ken Huff

My dad was in Shanghai in 1935 and I was looking for a good portrait so to speak of the historical context.

This was excellent. Thanks,

CM

My father-in-law, (still living) was a British prisoner of war sent to a prison camp in Shanghai. They separated the women/children from the men. He tells tales of horror and atrocities at the hands of the Japanese soldiers. They survived on the kindness of a Greek family that threw food over the fence, at times at great cost (beaten by Japanese soldiers). He still bears the prison number tattoo on his arm to this day. He thanks every US Marine he comes across, as they liberated his camp.