By Charles Hilbert

Years after he had saved the world from the ambitions of Napoleon, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, was asked by his friend, George William Chad, to recall the “best thing” he had ever done as a soldier. Perhaps Chad expected him to name one of his victories gained in the hard-fought Peninsula War: Talavera, Salamanca, Badajoz, or the capture of Cuidad Rodrigo. Perhaps he anticipated the Duke’s reply to include the name of a small town in Belgium where throughout a long day of savage fighting the fate of Europe hung in the balance, the Old Guard died, and Napoleon fled his last battlefield. But, perhaps Chad was somewhat surprised at the Duke’s laconic response: “Assaye.”

Arthur Wesley, then 28 years old and colonel of the 33rd Foot, landed in Calcutta on February 17, 1797. He had not yet reassumed the original spelling of the family name, which had been shortened sometime after the end of the 12th century when a Wellesley had ventured to Ireland as standard bearer to Henry II. Ten years before his arrival in India his older brother, Richard, Lord Mornington, had purchased a commission for him as ensign in the 73rd Highland Regiment. The purchase system probably produced more bad officers than good, but as the Duke would later note with approval, “it kept the command of the army in the hands of men of estate and family … [which] ensured loyalty to the established order of society.”

The future duke spent the next 12 months engaged in an endless round of symposia interrupted by an aborted mission to attack the Dutch in Java. Things began to get interesting when Lord Mornington arrived in India as Governor General in May 1798 along with Arthur’s younger brother, Henry, as his secretary. They were both calling themselves “Wellesley” and Arthur soon followed his brothers’ example.

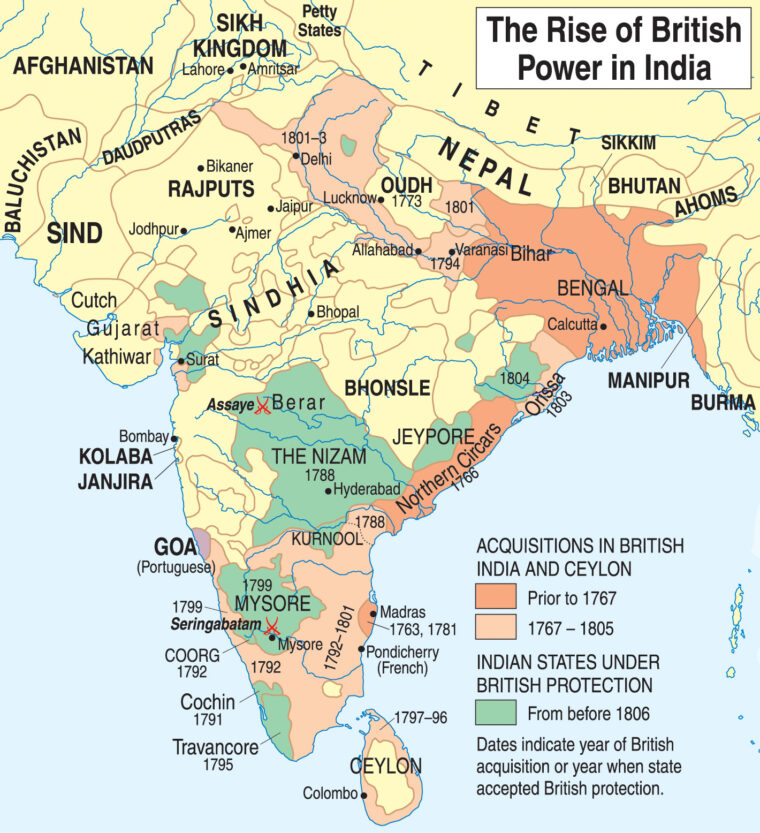

By all accounts Lord Mornington’s designs were imperialistic and contrary to the general attitude of the British East India Company, which had, since its inception in 1600, been more interested in the acquisition of trade goods than of territory in India. However, in order to protect its interests, the Company was gradually compelled to become embroiled in the quagmire of Indian politics, and eventually ended up a political entity itself, ruling the three presidencies of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay. The governors of each presidency were, at first, equal in authority, but by virtue of the Regulating Act in 1773, Parliament turned the governor of Bengal into the Governor General of India. Ten years later, the India Act of 1784 stipulated that the Governor General was to be nominated and paid by the Company, but appointed by the Crown and answerable to a board of Control composed of government ministers.

Thus, while Mornington was an employee of the East India Company, he was also an appointee of the British Government. With that in mind he immediately took measures which would not only further his own ambitions, but also protect the interests of his mother country. These, Mornington felt, were threatened by Napoleon’s arrival in Egypt and correspondence with Tippoo Sultan, ruler of Mysore. Indeed, one of Napoleon’s goals for the Egyptian venture was to weaken Britain in India.

Six years before, Tippoo, also known as “The Tiger of Mysore,” had been deprived of half his dominions by the British East India Company’s former Governor General, Lord Cornwallis. Tippoo was not well disposed toward the English. He was, in fact, an ardent admirer of the French Revolution, calling himself “Citizen Tippoo,” and maintaining an army trained and led by Frenchmen. He was reputed to be engaged in negotiations with Napoleon and was expecting a shipload of French reinforcements from their island colony, Mauritius, in the Arabian Sea. Mornington, receiving this intelligence in June, was all for an immediate attack on Mysore. Arthur advised against it; the French reinforcements in reality amounted to less than 200 men, and it would take some time to mobilize the East India Company’s army. The Governor General took his brother’s advice and turned his attention northward to the Nizam of Hyderabad.

The Nizam’s armies were also led by Frenchmen. Here the commander was a man named Piron. Although Piron’s employer, the Nizam, was an autocratic monarch, Piron was a fanatical supporter of the Revolution and preached liberté, egalité, fraternité. In addition, he was in close contact with the Nizam’s rival to the south, Tippoo.

To the north and west of the Nizam was the Mahratta Confederacy whose light cavalry had decimated the heavy squadrons of the Mogul Empire some 90 years before. In 1798, they held the ancient capital Delhi and paraded the captive Mogul Emperor, Shah Alam II, as a symbol of their legitimacy.

The Nizam trusted neither Tippoo to his south, nor the Mahrattas to his north, nor his own French officers. Indeed, he had negotiated with the former Governor General, Sir John Shore, with the object of replacing his French officers with British, and willingly re-opened negotiations with Lord Mornington to that effect. Mornington wanted Piron and the French gone altogether, but Mornington also had to be concerned that the Revolution-loving Piron would enter the service of Tippoo, who, as an implacable enemy of England, was merely awaiting his chance for terrible revenge.

On September 1, 1798, the Nizam signed a treaty agreeing to dismiss his French officers and become a protectorate of the English and their East India Company. In return he would receive a large sum of money and some of Tippoo’s territory. With this success in hand, Lord Mornington sent the 33rd and Arthur Wellesley south to Madras to begin preparations against Tippoo in Mysore. The French officers in the Nizam’s service weren’t about to just up and leave town. But by October the Nizam, in collusion with the British, had, by rumor and bribery, turned his troops against their French officers. The French were saved only by the timely arrival of six battalions of British redcoats.

For the next four months Lord Mornington negotiated with Tippoo regarding dismissal of his French officers and reception of a British ambassador. Tippoo procrastinated and prevaricated, hoping for reinforcements from Napoleon. Finally, in December, the Governor General ordered a force assembled at Vellore, about 100 miles west of Madras and less than 200 miles east of Tippoo’s capital, Seringapatam.

Arthur Wellesley was in temporary command, awaiting the arrival of General George Harris. Arthur had served under the Duke of York in Flanders in 1794 and there, as a result of the inattention and incompetence of his fellow officers, had learned “what one ought not to do.” Four years later, in camp at Vellore, he left nothing to his subordinates, writing dispatch after dispatch regarding supplies while at the same time whipping the army into fighting shape.

In December, Wellesley was given command of the Nizam’s contingent upon the death of Colonel Henry Harvey Aston who was killed in a duel with a fellow officer. By February 3—negotiations having achieved nothing—the army was on the move with General Harris in command. Accompanying the 36,000 combat troops was what Wellesley called a “monstrous equipment”—200,000 camp followers of every description and probably at least as many, if not more, baggage animals. As they marched toward Seringapatam from the east, the Bombay Army, under the command of General James Stuart, was approaching from the west. Marching 10 miles a day, in a hollow square seven miles long and three wide, the Madras force crossed the border into Mysore on March 5. The next day, General Stuart defeated Tippoo near Periapatam some miles to the west of Seringapatam.

Having failed to stop Stuart’s advance, Tippoo hurried eastward to attack Harris. On the 27th he met the combined forces of the East India Company and the Nizam at Malvilly. Tippoo personally led his cavalry against the British right, but was repulsed at bayonet point. His own infantry, advancing in column as was the French tactic, were shot to pieces by the British formed in line of battle.

By April 5, General Harris had encamped to the west of Seringapatam. The jungle between the camp and the city wall was full of Tippoo’s men. From the concealment of tangled bamboo thickets called “topes” they fired rockets into the British position. Wellesley and the 33rd were ordered to clear the “Sultanpettah Tope.”

It was night; the jungle ahead was a wall of impenetrable black, while behind glowed the lights of the British camp. Wellesley’s soldiers stumbled through deep irrigation ditches and dense vegetation. In the dark they were fired on; rockets and musket balls raked their ranks and in the confusion they fired on each other. Twelve soldiers who had gotten too far ahead of the rest, and had possibly stumbled right into the enemy’s position, were taken prisoner. A spent ball struck Wellesley on the knee. He became separated from his men but managed to find his way back to camp. The 12 captives were taken into Seringapatam where Tippoo’s men hammered nails into their skulls or strangled them. Wellesley never forgot the night action at Sultanpettah Tope. In the daylight of April 6, he attacked and took the position.

On the same day, all of Tippoo’s advanced posts were cleared and siege-works were begun. Even as the British guns inched closer to Seringapatam, fruitless negotiations continued. The Bombay Army arrived on April 14 and took up a position north of the Madras force. By May 3, British guns had opened a sizable breach in the southwest angle of the wall. The order to attack the next day was given to Major General Baird, who had spent three and a half years as Tippoo’s prisoner.

The Tiger of Mysore was having lunch on May 4 when at 10 minutes past 1 pm Baird stood up in the British forward trench and ordered his men to advance. They were greeted by an intense fire of rockets and muskets for the six minutes or so it took them to cross the waist-deep moat and clamber to the top of the breach.

Wrote one witness, a soldier named Lachlan Macquarie: “As Lieutenant Colonel James Dunlop was leading in the Bombay European Flank Companies up the Breach, he was met and opposed in the middle of it by one of Tippoo’s Sirdars—who made a desperate cut with his sword at the Colonel … but which he was fortunately able to parry … and instantly making a cut with his sword at the Sirdar across the Breast … laid it open, and wounded him mortally, the Sirdar, however, had still strength enough left to make a second cut at Colonel Dunlop, across his Right Wrist … cutting it almost quite through; … Tippoo’s Sirdar immediately on this reeled backward … and fell on the Breach … where he was instantly dispatched by the Soldiers as they passed him.… Colonel Dunlop after being thus severely wounded, still went on at the Head of his men until he gained possession of the Top of the Breach.”

Once there, according to plan, Baird followed the circuit of the wall to the right, while Dunlop turned left. They each continued on, the left exposed to flanking fire from the inner defenses, the right driving Tippoo’s men before them. After hard fighting, the inner fortifications were taken and the two assault parties met on the rampart over the eastern gate.

The Tiger of Mysore lived up to his name. Instead of fleeing to safety, he fought his way toward the gate of the interior fortifications. Wounded three times, his horse shot from under him, he lay in the gateway upon a heap of the slain. As British soldiers entered the gate, one of them approached Tippoo and reached forward to despoil him of his rich accouterments. The moribund Sultan struck with what remained of his strength, cutting open the Englishman’s knee with his sword. The soldier stepped back, took aim and shot him in the head.

During all this fighting, Wellesley had commanded the reserve. As dusk fell he entered the fort and joined the search for Tippoo’s body. In the flickering light of torches Wellesley’s men discovered it, still warm. The eyes were open. Wellesley knelt and took his pulse, but the Tiger of Mysore was dead.

General Harris appointed Colonel Wellesley Governor of Seringapatam. Although Baird was Wellesley’s senior, Harris thought it unwise to leave a former captive in charge of his former captors, who were as ill disposed toward him as he was to them. When Harris left in July 1799, Wellesley took command of Mysore. He spent the rest of the year and the beginning of 1800 engaged in myriad administrative duties. Meanwhile his older brother Richard, Lord Mornington, was upgraded from Earl to Marquess, becoming Marquess Wellesley.

In May Arthur Wellesley took the field against a freebooter named Dhoondiah Waugh, who had had a lucky escape from Tippoo’s dungeon at the time of the fall of Seringapatam and had since returned to the life of a brigand, which had caused his incarceration in the first place. Wellesley beat him at his own game of hit-and-run guerrilla warfare, and by September had him pinned between his own (Wellesley’s) men and a force commanded by Colonel James Stevenson. A sharp battle ensued.

In a letter to a friend the day after the battle, Wellesley wrote: “My dear Colonel, I have the pleasure to inform you that I gained a complete victory yesterday in an action with Dhoondiah’s Army, in which he was killed…I charged them with the 19th and 25th Dragoons, and the 1st and 2nd Regiments of Native Cavalry, and drove them till they dispersed, and were scattered over all parts of the country. I then returned to the Camp, and got possession of Elephants, Camels, Baggage, &c, &c which were still upon the ground.” This was the first and last time Arthur Wellesley would personally lead a cavalry charge.

At the end of the year Wellesley was appointed to lead an expedition to Egypt, and though superseded in command by a senior officer, he was ready to sail when he became ill with fever. The ship he was to have sailed on sank in the Red Sea leaving no survivors. After recovering from the fever, Wellesley returned to Seringapatam in May 1801 to continue his administration of the country. A year later, in April 1802, he was promoted to major-general.

Meanwhile conditions to the north in the Mahratta Confederacy were shifting. The chief of the confederacy, which had been carved from the deteriorating Mogul Empire, was called the Peshwar, but real power was in the hands of Daulat Rao Scindiah. Through his deputy in Delhi, a Frenchman named Pierre Perron, Scindiah also controlled the last Mogul emperor, Alam Shah, and through him, all of Hindustan. Scindiah had inherited all this power upon the death of his uncle in 1794. He had also inherited his uncle’s feud with the house of Holkar.

During the negotiations that led to the Nizam of Hyderabad becoming a protectorate, the Governor General Marquess Wellesley had also been corresponding with the Peshwar seeking a similar accommodation. The Peshwar wasn’t interested; he had Scindiah to protect him and Scindiah had Perron’s battalions to back him up. But soon the situation took a tumble. In October 1802, Holkar took the field and defeated the combined forces of the Peshwar and Scindiah, a short while later seizing the former’s capital of Poonah. The Peshwar fled west to one of his forts and remained there, safely out of reach of Holkar, who merely installed his own puppet Peshwar named Amrut Rao. Scindiah sent message after message ordering Perron south to reinforce him against Holkar, but Perron wasn’t about to leave Delhi and give up his control of Alam Shah, who, upon the arrival of French troops promised by Napoleon, would be induced to turn Hindustan into a French protectorate.

Despite friendly assurances by the puppet Peshwar and Holkar himself, the British Resident left Poonah in late November, lest his presence there be construed as official recognition of Holkar’s puppet government. At the same time the Governor General, quick to capitalize on any bit of good luck that might add to the good fortune of the East India Company, England, and himself, quietly sent orders for the Madras force to assemble at Hurryhur on the northwestern border of Mysore. The Bombay Army and a contingent of the Nizam’s troops were also placed on alert.

The Governor General knew that with the Peshwar’s protector, Scindiah, defeated by Holkar, the Peshwar would have no choice but to follow in the footsteps of the Nizam and place himself under the protection of the British. A huge chunk of India would be added to the Company’s dominions, the turbulent Mahrattas would be weakened by the loss of their western coastal territories, and Marquess Wellesley’s imperialist desires would be partially satisfied.

The Peshwar arrived at the coastal town of Bassein at the end of December, and there, with his back to the wall, acceded to Mornington’s terms by means of the Treaty of Bassein on New Year’s Eve, 1802. His extensive dominions to the west of Nizam’s territory became a British protectorate. Hoping for a similar success, Marquess Wellesley sent Lieutenant Colonel John Collins to negotiate with Scindiah at the beginning of February 1803. Scindiah, along with Holkar and the Nizam’s neighbor to the northeast, the Bhoonslah of Berar, did not fancy themselves as British protectorates but made peaceful overtures. By the end of the month, Colonel Stevenson was leading the Nizam’s troops toward Poonah. He was still on his way when Arthur Wellesley set out from Hurryhur with some 12,000 infantry and cavalry on March 8. While Collins still negotiated with Scindiah, Scindiah negotiated with the Bhoonslah. Holkar saw the writing on the wall and headed north to his own dominions.

Arthur Wellesley left nothing to chance. In a dispatch of March 27, 1803, he wrote: “It is possible that the detachment of the army under my command in this country may remain in it till after the rains shall have commenced, and the rivers … shall have filled … the sooner we begin to make boats the better … I enclose a memorandum which will point out … the mode in which they ought to be made.” He was thinking ahead; the rivers were not yet risen and were easily forded and after a month of marching his goal was in sight. On April 19, he received word that the new Peshwar, Amrut Rao, was about to burn Poonah rather than have it fall into the hands of the English. Wellesley set out that night with his cavalry and reached Poonah by 2 pm on the 20th. Amrut Rao had already left.

The restored, British-protected Peshwar took his time but finally arrived back in Poonah on May 13. That same day, the Governor General sent letters to Scindiah and the Bhoonslah officially notifying them of the Treaty of Bassein, offering them the same terms, and warning them that the presence of their armies on the Nizam’s border could possibly be interpreted as a hostile gesture and might, in fact, lead to open hostilities between them and the Nizam’s protectors, the British. Negotiations continued for the next two months. The British wanted the Mahrattas to withdraw; the latter agreed to retire only if the British would do the same. In June the Marquess Wellesley gave his brother, Major General Arthur Wellesley, plenipotentiary powers with regard to the Mahrattas. At the same time the French fleet arrived at Pondicheri, some miles to the south of Madras.

Arthur Wellesley’s letter of July 17, 1803, to Colonel Collins, resident at Scindiah’s camp, reveals his understanding of the military and political situation: “If Dowlut Rao Scindiah perseveres in retaining his hostile position upon the Nizam’s frontier … I must consider him in a state of hostility with the Company … I have not fixed a day on which Dowlut Rao Scindiah shall depart … It leaves me the choice of the day on which to commence my operations, supposing them to be necessary; it renders greater the probability that I shall strike the first blow.”

At the beginning of August, convinced of the Mahrattas’ insincerity, Collins departed Scindiah’s camp, and war was declared on the seventh of the month. Arthur reached the pettah, or outworks, of Fort Ahmednuggur on the eighth. As one of his Mahratta allies said, “These English … came here in the morning, looked at the Pettah wall, walked over it, killed all the garrison and returned to breakfast!” In reality it was not that fast. In four days, Arthur captured the fort. A few days later he began the hunt for Scindiah.

At the same time, General Gerard Lake, commander of the Bengal Army, having been ordered by the Governor General to destroy Perron’s force before the rains, entered Mahratta territory on August 29. He succeeded in taking the fortress of Alighur on September 4th. Lake then received a letter from Perron on the 7th, telling him of Perron’s resignation from the service of Daulat Rao Scindiah, and asking for safe passage for his family and himself to Lucknow and thence to France. Lake granted all of Perron’s requests. The French at the port of Pondicheri had been no help; they were besieged and later captured. Lake then defeated Perron’s French successor and “liberated” the Emperor Shah Alam II on September 16.

Meanwhile, Arthur Wellesley was engaged in a war of maneuver, intent on bringing Scindiah to battle. Some of Perron’s brigades had reached the camp of Scindiah and the Bhoonslah. They were commanded by two Frenchmen named Dupont and Saleur and a German named Pohlman.

On September 21, Wellesley and Stevenson met at Bednapur and planned a two-pronged attack for the 24th. A line of hills separated them from their enemies to the north, so it was decided that Stevenson would take the western pass and Wellesley the eastern. The future duke later wrote: “This separation was necessary … because both corps could not pass through the same defiles in one day … [I]f we left open one of the roads through these hills, the enemy might have passed to the southward while we were going to the northward and then the action would have been delayed.”

Perhaps the Duke planned to squeeze Scindiah between his own force and Stevenson’s in a movement akin to that which had proved the end of Dhoondiah Waugh. Things did not, however, turn out according to plan.

Owing to the large numbers of Mahratta cavalry scattered throughout the vicinity, Wellesley had to depend on local guides and scouts. These had reported to him that the enemy was at Bokerdun. Wellesley reasonably assumed that they meant the town of Bokerdun, so he timed his march of the 23rd to bring his army within 12 miles of his objective. The Mahratta cavalry was indeed at Bokerdun, but the infantry was at Assaye, about six or eight miles from the town of Bokerdun in the district of Bokerdun. Scindiah and the Bhoonslah had filled not only the town, but also the whole area with their armies.

On the morning of September 23, Wellesley, approaching from the southeast, learned that the enemy was six miles closer than he had supposed. In addition, he was told that the cavalry had left and that the infantry was about to leave. He was determined not to let them get away. He sent a message to Stevenson and advanced toward the Mahratta infantry.

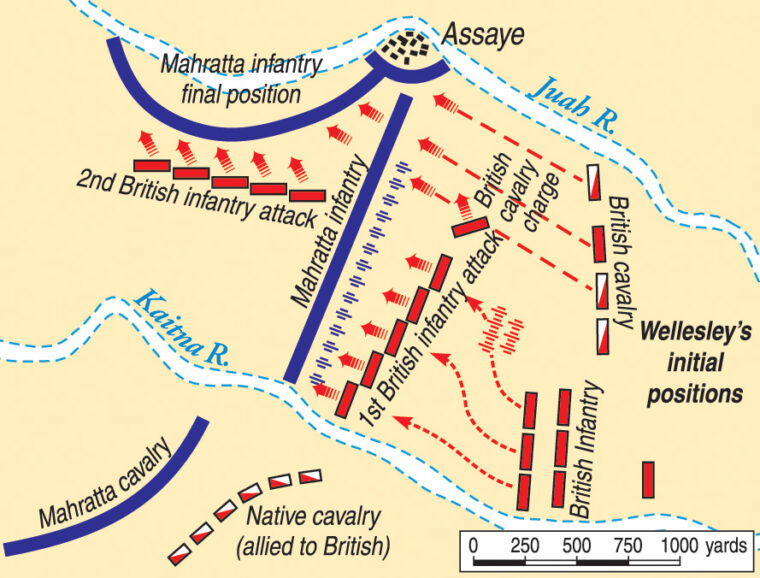

At about 1 pm he came in sight of his adversaries. They were camped on the north bank of the Kaitna river. He discovered that, contrary to what he had been told, the cavalry had not gone and that, in fact, the camp stretched for seven miles, between Bokerdun on their right and Assaye on their left. Behind Assaye flowed the Juah River, which joined the Kaitna below the town. The Mahratta forces seem to have been drawn up in line of battle, as if to oppose a frontal assault across the Kaitna. Scindiah and his cavalry were on the right, the Bhoonslah in the center and the French-led battalions on the left. The Mahrattas had impounded all the local water-craft.

Wellesley had about 4,500 men, the Mahrattas perhaps 10 times that many. The English had 20 cannon, their opponents 100. Withdrawal in the face of the Mahratta light cavalry would have been suicide; harrying a retreating enemy was their favorite tactic, and one which they had used to good effect against the heavily armored Moguls. Wellesley’s troops had already marched 24 miles that day and his only option was offensive. He resolved to cross the Kaitna, draw his line up at a right angle to his enemy in the narrow land between the two rivers—thus denying the Mahratta cavalry room to maneuver—then attack the Mahratta left and roll up their line.

His guides informed him that there was no way across. Having had enough experience with native duplicity during the negotiations with Scindiah and Tippoo, he went himself to investigate. He reasoned that the two villages would not have been built so near to one another unless there were some easy means of communication between them, such as a ford. A member of his staff sent to scout the area returned to report the reality of the Major General quite logical deduction.

Wellesley then advanced with the 74th and 78th Regiments, plus four battalions of sepoys (native soldiers). Slowed by their artillery train, the English and their allies advanced to the river as the enemy opened fire with their more numerous field pieces. Shot and shell filled the air as they crossed. The head of the general’s orderly disappeared in a spray of blood and brains, his panicked mount bucking amid the surviving staff officers until it shook off its headless rider.

As his troops gained the north bank, Wellesley began to form line of battle with the Kaitna on his left and the Juah on his right. Scindiah’s European officers weren’t about to let Wellesley flank them; they began to change their front so that their left rested on Assaye and their right on the Kaitna. As Wellesley drew up his infantry in two lines, with the cavalry in a third, the enemy fired grape and chainshot upon his force, inflicting casualties. On the far right of his line he stationed Colonel John Orrock and the piquets (a loose formation of infantry) with the 74th in support. Wellesley cautioned Orrock not to get too close to Assaye, which was full of the enemy’s infantry and guns. It seemed that Wellesley now intended to withhold his right and advance his left against the Mahratta right, pushing it back to the Juah which would leave their left in Assaye cut off. This would force the Mahratta left to either withdraw or to fight unsupported.

Wellesley saw that the Mahratta line, by virtue of its numerical superiority, extended its left beyond his own right. He ordered Orrock to move the piquets right. This would leave a gap between the piquets and the infantry formed in line of battle, which would be filled by detachments from the British left. The British line would thus be extended in order to prevent a flanking movement by the Mahrattas. The enemy fire was causing too many casualties, so it is possible that Wellesley ordered the left to advance at the same time.

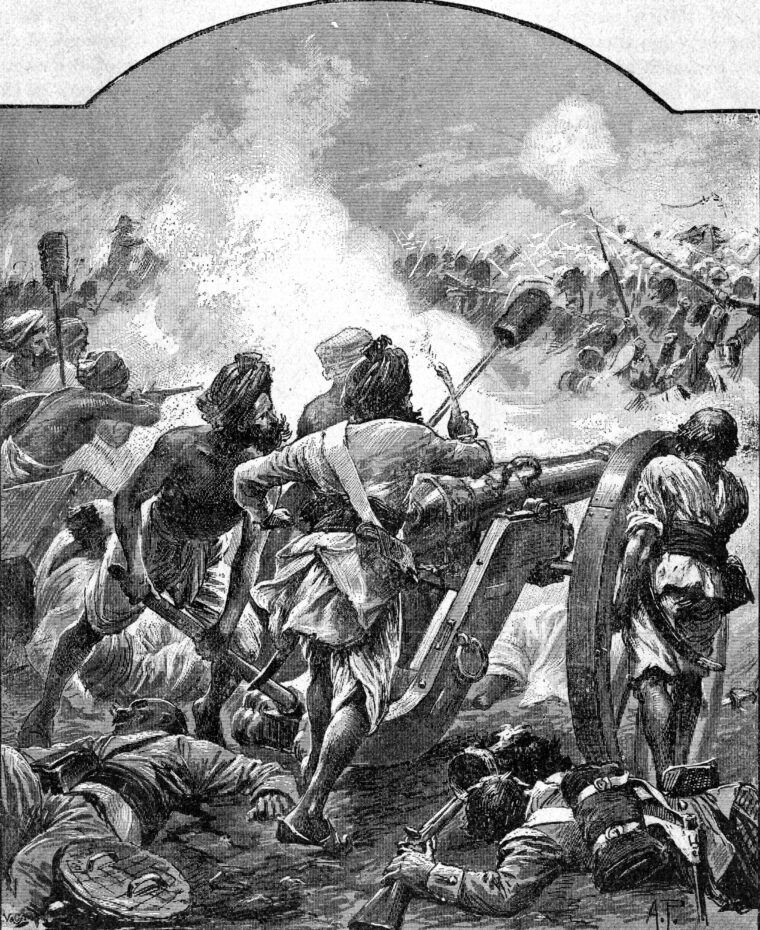

Into the teeth of a heavy cannonade the British left advanced, “without firing two rounds,” and engaged the enemy’s first line of guns and infantry. Colonel Orrock, perhaps misunderstanding his orders, continued his movement to the right. The 74th, ordered to support the piquets, followed. On the left, “Scindiah’s infantry … were driven from their guns only by the bayonet, and some of the corps retreated in great order and formed again,” according to Wellesley’s later reports.

The British left “then moved on in equally good order and resolution to the second line of guns, from which they very soon drove the enemy.” Suddenly, some of the gunners of the first line, who had feigned death, leapt to their feet, turned their guns around, and fired into the backs of the English and sepoys. Wellesley ordered the 78th and a regiment of native cavalry to dispatch them. This no doubt necessitated some maneuvering as the 78th had to change their front under fire. Just then the General’s horse was shot dead under him.

On the right the 74th had followed the piquets and, advancing through a storm of flying metal, had actually taken the first line of guns in front of Assaye. Their losses were terrible; they hadn’t enough men to hold the ground they had just taken, and the fire from the Mahratta second line was unbearable. What was left of the piquets and the 74th was forced to withdraw.

Seeing their enemy retreating, the Mahratta cavalry charged the remnants of Orrock’s piquets and the 74th. With their curved swords and long bamboo lances they mercilessly cut and stabbed the straggling wounded. At this point, had it not been for the steadfastness of the 74th and a timely counter charge by the 19th Light Dragoons, the British right would have collapsed. Then, with the British left driving the Mahratta right, Wellesley, on his third horse of the day (the second being wounded by a pike or lance), arrived on his own right with the 78th and the 4th Native Cavalry and drove the Mahrattas out of Assaye. By then it was almost 6 pm and the fighting subsided.

Scindiah and the Bhoonslah left 1,200 dead and 100 cannon on the battlefield. Ten of their European officers were taken prisoner. The British cavalry was scattered and in no condition to pursue the fleeing enemy. The infantry were exhausted, having fought steadily for three hours after a march of 24 miles. Four hundred twenty eight of them would march no more. Over a thousand had been wounded out of a total force of some 4,500. The shattered 74th had been led off the field by its quartermaster, all other officers having been wounded or killed. Five hundred had attacked the guns at Assaye; 80 were still on their feet.

Wellesley sat down with his head between his knees and didn’t move for a long time. He later wandered into the yard of a nearby farm, fell asleep and dreamed that everyone was dead.

Colonel Stevenson arrived on the night of the 24th, a full day after the end of the fighting. His guides had gotten lost in the hills, causing one to wonder whose side they were really on. On the 26th, Stevenson set out after Scindiah and the Bhoonslah. Their recent defeat seemed to have had a detrimental effect on their friendship and they soon parted company. While Wellesley guarded against invasion of the Nizam’s territory, Stevenson took Burhampoor on October 15 and Asseeghur six days later.

Typically indecisive negotiations followed between Wellesley and Scindiah with no result. By November 29, Wellesley and Stevenson joined forces once again, catching the Bhoonslah’s infantry and Scindiah’s cavalry outside the village of Argaum. The British line emerged from the concealment of a cornfield into the fire of the enemy’s guns. The same sepoys who had fought so well at Assaye panicked and were only reformed with difficulty by Wellesley personally, who then led them to an easy victory.

Two weeks later the impregnable fortress of Gwalihghur fell to the combined forces, mainly because its garrison decided not to defend it. Two days later the Bhoonslah sued for peace. At the end of December 1803, Scindiah capitulated. Thus large portions of the subcontinent fell under the control of the East India Company. Holkar hung on until 1805, when the new Governor General granted him more than equitable terms, but by 1817 the company controlled his lands as well.

Wellesley fought his last action in India on February 5, 1804, against a band of freebooters plundering in Nizam’s territory. He defeated them decisively. By now he was tired of India, his health was suffering, and he wanted to return home. In March 1805, he took ship for England. On the way he stopped at a small island named St. Helena. Ten years later the island would receive another famous visitor whose permanent retirement there was the result of a chance meeting with Arthur Wellesley at a crossroads in Belgium.

The Duke of Wellington never forgot his service in India and the hard fought battle between the Kaitna and the Juah Rivers. Years after the plodding torment and savage encounters of Spain and the murderous fury of the bloody day at Waterloo, the only answer he could give to his friend Chad’s question on the best thing he had ever done as a soldier was “Assaye.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments