By Vince Hawkins

The War of Spanish Succession, fought between 1701 and 1711, witnessed the emergence of some of Europe’s greatest military commanders. Men such as England’s John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, Austria’s Prince Eugene of Savoy, and France’s Marshal Claude-Louis Hector, Duc de Villars, led their resplendently uniformed troops across the fields of Europe, demonstrating their skill and genius for warfare. They turned small, often nondescript villages and towns into household words that would forever mark the annals of a period of military history often known as the “Lace Wars.” This period also witnessed another type of conflict, one that was conducted in the salons and courts of the great capitals of Europe, that of diplomacy and international coalitions.

Choosing an Heir and Choosing Sides

As its name suggests, the War of Spanish Succession was fought over who would ascend the throne of Spain. When Charles II, the last of the Spanish Hapsburg line, died childless, he left a major European throne without a legitimate heir. Two claimants to the throne emerged, Louis XIV of France and Leopold I, Hapsburg Emperor of Austria. Louis’s claim was based on the fact that he was the son of the eldest daughter of Philip III of Spain and the husband of the eldest daughter of Philip IV of Spain, while Leopold’s claim stemmed from his being the son of the youngest daughter of Philip III and husband of the youngest daughter of Philip IV. Because neither England nor Holland wanted a Spain allied to either France or Austria, Louis opted to claim the throne in the name of his second grandson, Philip of Anjou, while Leopold claimed it in the name of his second son, the Archduke Charles.

In his will, Charles II had declared Philip of Anjou as his rightful heir. Thus on November 1, 1700, Philip was proclaimed Philip V and ascended the throne of Spain. England and Holland immediately prepared for war, as did Austria, because Leopold still maintained his claim over the Spanish Netherlands. By September 1701, the Grand Alliance against France had been formed. The Alliance consisted of Austria, England, Holland, Brandenburg-Prussia, Denmark, most of the German states, and later Portugal and eventually Savoy, which changed sides during the conflict. France’s allies were Spain, Mantua, Cologne, and later Bavaria.

Marlborough’s First Victory is Followed by Frustration

With the sides chosen and the conflict already under way, England escalated the situation by declaring war on May 15, 1702, and sending to Holland John Churchill, Earl of Marlborough and recently appointed captain general of combined English and Dutch forces. In June Marlborough invaded the Spanish Netherlands, where for the next two years he maneuvered against superior French armies in the field and recalcitrant Dutch officials from The Hague. On four separate occasions, Marlborough’s attempts to bring the French Army to battle were frustrated by Dutch governmental deputies attached to his headquarters who held veto power over his using Dutch troops in battle.

Finally, on August 13, 1704, Marlborough was able to demonstrate what allies who work together could accomplish. Having united his army with the forces of Prince Eugene, the two generals simultaneously attacked Marshal Tallard’s Franco-Bavarian army at Blenheim. In a masterpiece of cooperation and coordination, Marlborough and Eugene shattered Tallard’s army, killing, wounding, or capturing some 38,600 men, over half of the Franco-Bavarian force, for a combined allied loss of 13,000 killed and wounded. Their magnificent victory virtually destroyed the prestige of France and her armies, and forced the Elector of Bavaria to flee his country, which was subsequently annexed by Austria.

Following his great victory, Captain General John Churchill, now 1st Duke of Marlborough, was forced to concede that while Blenheim had been a tactical triumph it had also proven, in the overall context of the war, to be strategically indecisive. The war in the Low Countries continued unabated, progressing in its usual slow, often seemingly aimless manner. Marlborough was continually confronted by indecision, excessive caution, and an apparent lack of commitment on the part of his Dutch allies, who repeatedly frustrated his offensive plans and resulted in his 1705 campaign degenerating into a wasteful stalemate. Marlborough’s chief opponent in Flanders, Marshal François de Neufville, the Duke of Villeroi, took full if unintentional advantage of the Dutch lack of offensive zeal to stay just out of Marlborough’s reach, thus avoiding any action that might force a decisive result. As a consequence, Marlborough’s main accomplishment in 1705 was diplomatic. Making a prolonged tour of all allied headquarters, he managed by his engaging personality and the laurels of his victories to solidify the politically strained alliance.

The Forcing of the Lines of Brabant

The one significant military exploit during this campaign, and one that greatly unnerved Villeroi, was Marlborough’s forcing the Lines of Brabant, a 60-mile-long series of fortifications, earthworks, and obstacles that stretched from the sea at Antwerp to the Meuse River at Namur. In a cunningly deceptive plan, kept secret from all his Dutch allies save one—the elderly Field Marshal Overkirk—Marlborough let it be known that he would make a feint to the north and then attack the Lines at their weakest point in the south. When this information reached the ears of Villeroi, it seemed quite logical and was therefore believed to be Marlborough’s true design.

In fact, his real plan was the exact opposite. Overkirk, having been taken into Marlborough’s confidence, was to cross the Meuse by four bridges and build seven more, as if preparing for the crossing of a major army. To further guarantee success, Marlborough ordered 20 more bridges to be built, thus leaving no doubt where he intended to strike. In response to these clear warning signs, Villeroi dispatched 40,000 men to the threatened south. On July 18, 1705, as the French marched south, Overkirk reversed his direction and quickly began marching north, forming the rear of Marlborough’s main force which had started moving that same night.

At dawn on July 19, English troops appeared opposite the town of Elixem, considered one of the strongest points on the Lines. As such it was lightly manned, and with a quick assault lasting less than two hours the vaunted Lines of Brabant were passed. Marlborough, displaying one of his few shortcomings as a commander, charged with a squadron of British cavalry into the thick of a mounted melée. While dodging the sabre stroke of a Bavarian trooper, Marlborough fell from his horse, causing Lord George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney, to comment, “See what a happy man he is! I believe this pleases him as much as Hochstädt [Blenheim] does.”

Despite the success of his plan and the capture of 3,000 prisoners, including the enemy general, Marlborough’s desire to exploit the victory by taking the town of Louvain—a mere seven miles away—was again thwarted as Overkirk’s regiments, having marched 27 miles to reach the field, were too exhausted for further action. Still, Marlborough’s penetration of the Lines allowed him to advance far enough to place his army in a position to turn Villeroi’s right flank and rear. On ground that would one day witness the Battle of Waterloo, Marlborough deployed his army for battle. Villeroi, realizing that he was now in a dangerous situation and that his enemy threatened both Louvain and Brussels, sacrificed the former and moved his army to defend the latter. Marlborough, convinced that here was a chance to conquer all of the Spanish Netherlands in one quick stroke, advocated an immediate attack. But once again the Dutch used their veto, and the discouraged general had no choice but to hold his ground. The remainder of the campaign season was thus frittered away and, as after Blenheim, a great achievement—having forced the Lines of Brabant—came to naught.

In 1706 Marlborough suggested that a campaign be launched in Italy. His plan was to join forces with Prince Eugene of Savoy and together they would relieve the siege of Turin, Savoy’s capital, thus freeing the Duke of Savoy and his army. Then, in conjunction with the English Mediterranean fleet, their combined forces would attack the French city of Toulon. Despite receiving the backing of his sovereign, Queen Anne, the remainder of the alliance objected to Marlborough’s otherwise competent strategic plan, and he was forced to resume operations in Flanders.

France Changes Tactics and Decides to Come Out and Fight

In typical style, Marlborough opened the campaign with an offensive against the fortress of Namur, trying once again to lure the French into battle. He doubted that the French would come out and fight, and in a despondent tone he wrote to his friend, Sidney, Earl of Godolphin, “God knows I go with a heavy heart, for I have no hope of doing anything considerable, unless the French do what I am very confident they will not, namely, come out and fight.”

Nevertheless, Marlborough gave orders to concentrate the allied forces, and by May 17 the English and Dutch troops were assembled at Tongres waiting for the Hessians and Hanoverians. Since the Prussians were being held back on the orders of their king until certain grievances were met, Marlborough decided to act without them. As he began his advance toward Namur, he was surprised to learn that the French were already on the move. Villeroi had crossed the Dyle River and was marching toward Tirlemont (Tienen). The French had changed their strategy and now seemed to be actively seeking battle.

This change had come directly from Versailles. Informed that the war had put his treasury 25 million francs in debt, Louis XIV was considering negotiating a peace. The last campaign had shown France’s defensive strategy to be costly and ineffective. It was difficult for the generals because it forced them to spread their troops too thinly over too wide an area and it was proving detrimental to the soldiers’ morale. Further, it gave the enemy the advantage of the initiative, forcing the French to react instead of acting decisively.

Therefore, in order to strengthen his bargaining power, Louis ordered Marshal Villeroi onto the offensive, giving as his primary objective the fortress of Léau. Louis’s instructions to the marshal, however, contained a note of ambiguity. “Do not expose yourself to a general engagement without need, but do not avoid it with too much precaution.” The interpretation of these orders was left to Villeroi, who told the king that he believed it could be “advantageous to accept a battle, especially if the enemy were obliged to come and attack us.” Thus, in a decidedly singular occurrence contrary to the general conduct of the war, both belligerents were actively seeking a battle.

Marlborough was ecstatic at the prospect of at last engaging the enemy and quickly moved his army to intercept Villeroi. Writing to a Dutch official, Marlborough stated, “For my part, I think nothing could be more happy for the Allies than a battle since I have good reason to hope … we may have a complete victory.” On May 20, Marlborough learned that Villeroi had changed direction south and was moving toward the gap between the Mehaigne River and the Petite Gette stream. Sending orders for the Danish cavalry to join him with all haste, Marlborough turned his army south. By May 22 he was encamped near the village of Corswarem where he was joined by the Danish horse which, in obedience to his orders, had forced their march to reach him. At around 1 o’clock the following morning, Marlborough ordered his chief of staff, Earl William Cadogan, to reconnoiter the high ground between the Mehaigne and Gette for a suitable campground. Marlborough knew this area well and it was his intention to occupy the plateau around Ramillies, some 12 miles distant. Cadogan duly set off with the advance guard and the main army followed two hours later.

France’s Troops Assemble for the Battle of Ramillies

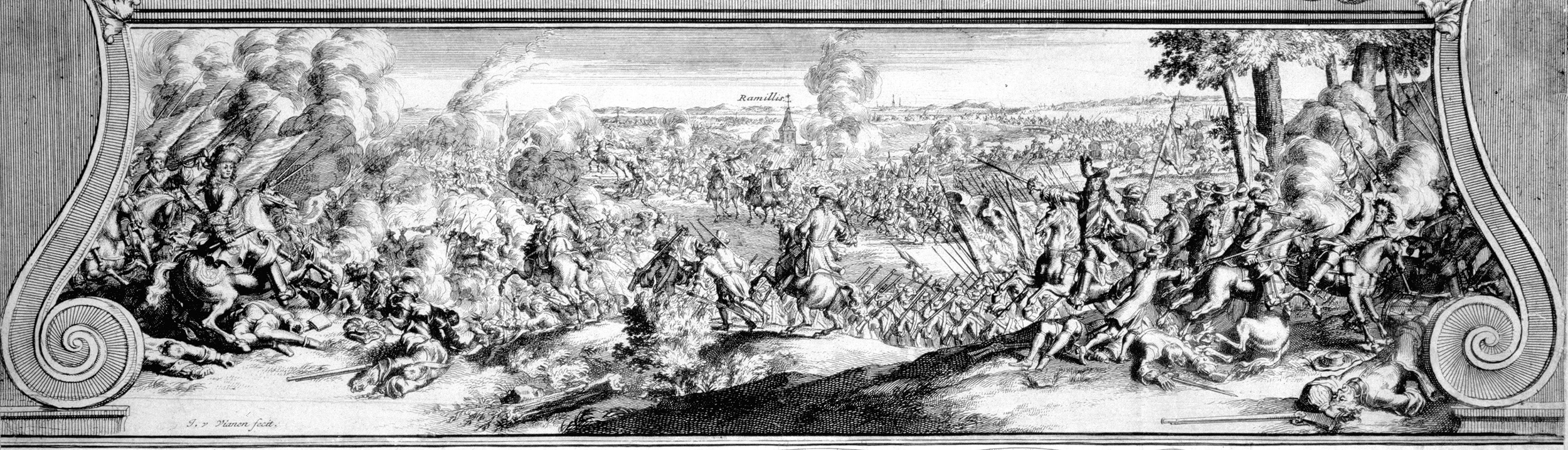

May 23, Whit Sunday, began with a heavy fog that shrouded the surrounding countryside. Around 8 am, just as the mist was beginning to lift from the plains and reveal the plateau ahead, Cadogan and his small cavalry escort stumbled onto a French patrol. A few scattered shots and the French withdrew, leaving Cadogan and his party to survey the area undisturbed. As the mist finally lifted, the sun broke through, just as it had at Blenheim, and revealed a startling sight. The woods they had just cleared opened up onto a large plain several miles long that swept up to the plateau around Ramillies. There, through his glass, Cadogan could see the French Army deploying for battle, the sun gleaming and sparkling off their weapons. The French were advancing in two great columns of infantry, their artillery train in the center, with their cavalry forward and ready for action. Cadogan immediately sent an aide-de-camp galloping back to inform the duke. Marlborough came riding up around 10 am, the army in eight great columns still struggling behind along roads turned to mud by recent rains.

A French officer, Brigadier de la Colonie, who was present on the plateau, described the sight: “There was nothing to impede the view—the whole force was seen in such fine array that it would be impossible to view a grander sight. The army had but just entered on the campaign, weather and fatigue had hardly yet had time to dim its brilliance…. The late Marquis de Goudrin, with whom I had the honor to ride during the march, remarked to me that France had surpassed itself in the quality of these troops; the enemy had no chance whatever of breaking them.” Even Marlborough himself was impressed with the spectacle, stating that the French Army before him was “the best of any he had ever seen.” He was also impressed with the disposition of the army and the apparent strength of its position.

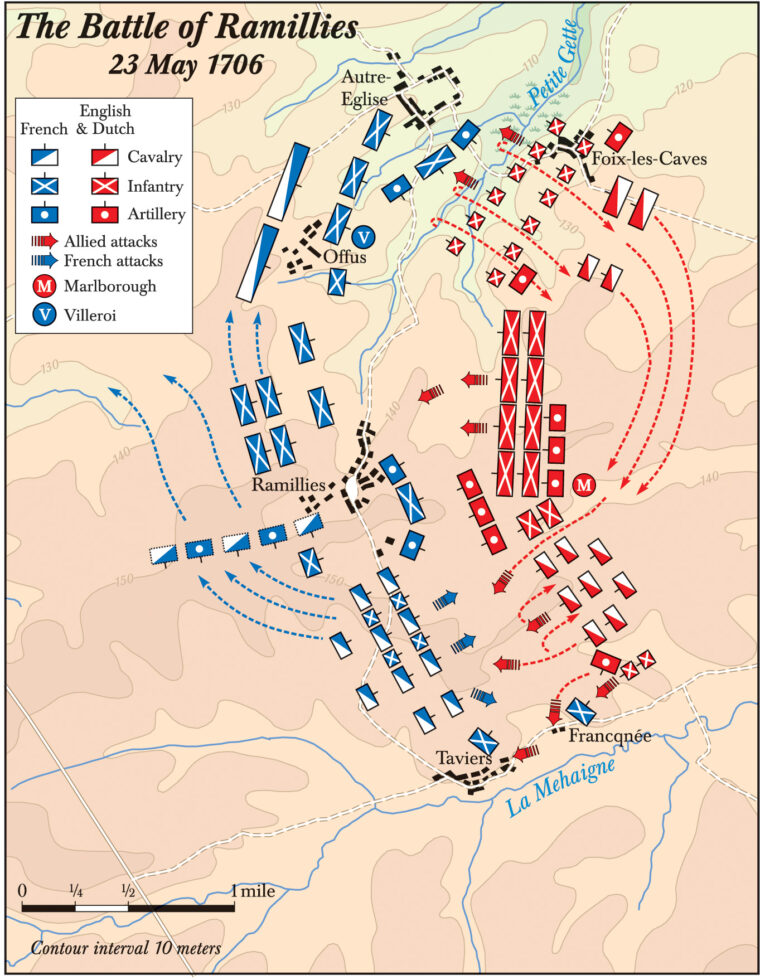

As Marlborough watched, Villeroi and his ally, Elector Max Emanuel of Bavaria, deployed their 60,000 French and Bavarians along a four-mile front, stretching in an arc from the villages of Francqnée and Taviers on the Mehaigne River on his right, through the village of Ramillies in his center, through the villages of Offus and Autre-Eglise on his left. Originating from a spring behind Ramillies and running along the front of the French left flank was the Petite Gette, with steep, slippery banks and swampy surrounding ground. The terrain along this line was open and undulating with numerous depressions and folds that hid one part of the field from another.

Ramillies itself lay on the plateau, which gave a good view to the north and east, while Taviers and Francq- née were in a lower plain, hidden almost completely from view save for their spires. Between Ramillies and Taviers was a large, open plain some two miles long. In all, the battlefield was strikingly similar to that of Blenheim.

Villeroi, however, was determined not to repeat the mistakes his compatriot had made at Blenheim. He deployed his army of 70 battalions of infantry, 132 squadrons of cavalry, and 70 guns with those errors in mind. He occupied Francqnée with a token force and Taviers with only a brigade of infantry. In the plain between Ramillies and Taviers he placed 82 squadrons of cavalry, intermixing them with strong infantry support. Among these, drawn up in the forefront, were 13 squadrons of the Household cavalry, “the gorgeous squadrons of the Maison du Roi, the Bodyguard, the Musketeers, the Horse Grenadiers, the Gendarmerie in their red coats,” wrote historian George Thomson. In and around Ramillies he placed 20 battalions, while the bulk of his infantry and the rest of the cavalry, some 50 squadrons, he positioned behind the Petite Gette from Ramillies through Offus to Autre-Eglise. Taking care to follow King Louis’s advice “to pay particular attention to that part which will bear the brunt of the first shock of English troops,” Villeroi positioned himself on a slight rise behind Offus. It was then that he noticed Marlborough’s English and Scottish battalions forming on the allied right, directly opposite the French left flank.

Villeroi’s dispositions, although giving his army a relatively strong position, had several major shortcomings. First, Villeroi himself was unable to see most of the battlefield from his position behind Offus, and his right flank was completely out of sight. Second, his line formed a concave arc, which would make it more difficult to shift troops along his front should he need to reinforce a certain position. Third, while the villages provided strong defensive bastions to his line, they were too far apart to be mutually supporting. Lastly, by standing on the defensive he gave the initiative to the enemy. Marlborough would make good use of these obvious advantages.

Marlborough’s Counter Strategy

About 11 am, having seen the French deployment, Marlborough accordingly disposed his army of Dutch, Danish, German, English, and Scottish troops, totaling some 62,000 men, in just under three hours. Twelve battalions of English and Scottish troops were positioned on his right, supported by 39 squadrons of English cavalry under the command of Lord George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney. These troops, among them the Guards, the Royal Scots, the Royal Welsh, and the Camerons, were the cream of the English Army. In his center he placed 58 battalions, two of which were English and several being Scottish units in Dutch service, under the command of “Red John of the Battles,” also known as the Duke of Argyll. On his left flank he positioned the bulk of his cavalry, 69 Dutch squadrons, directly opposite Villeroi’s cavalry, under the command of Dutch Count Hendrik van Nassau, Lord Overkirk. On his far left, opposite Francqnée, he placed four Dutch and Danish battalions.

While his infantry and cavalry were roughly equal to those of Villeroi—74 to 70 battalions and 123 to 132 squadrons—Marlborough had 120 guns to Villeroi’s 70, and enjoyed a 50 percent superiority in numbers as well as weight, since a hundred of these guns were the heavy 24-pounders. These he positioned with great care. Marlborough took as his position a slight rise in the terrain about halfway between Ramillies and Taviers and slightly to their east. From here he had a “panoramic view of almost the entire battlefield, from the spires of Francq- née and Taviers to the line of the Gette,” wrote Marlborough biographer Corelli Barnett.

Realizing that the decisive action must take place across the large rolling plain between Ramillies and Taviers, Marlborough’s plan was to upset the balance of the French position by getting them to shift their weight away from their center and right flank, thus enabling him to concentrate his main force against the plain. Because his lines were convex to those of Villeroi’s, he had the advantage of being able to quickly shift troops from one flank to another. Marlborough therefore decided upon a stratagem of deception. He would make a probing attack on his left toward the villages of Francq- née and Taviers, and a feint attack on his right against Offus and Autre-Eglise. If, as he hoped, Villeroi considered the advance of the British troops as the main attack and weakened his center and right to support his left, Marlborough would then quickly concentrate his strength and attack across the plain, splitting the French center and rolling up their line from right to left.

The Fighting Begins on the Right

His dispositions finished, Marlborough gave the order to attack, beginning on the right. “We began to make our lines of battle about eleven o’clock, but we had not all our troops till two in the afternoon, at which time I gave orders for attacking them.”Because Marlborough had intentionally deceived Orkney into believing that the British attack on the right was the main assault and not merely a feint, that worthy commander advanced with grim determination. Struggling across the Petite Gette and scrambling up the other side, the British troops endured a storm of artillery and musket fire. Locked in a desperate battle, Orkney later described it by saying, “I think I never had more shot about my ears … I endeavoured to possess myself of a village, which the French brought down a good part of their line to take possession of, and they were on one side of ye village, and I am on the other; but they always retired as we advanced.”

Reforming their lines and closing up their ranks, they continued to come on with that peculiar, quiet ferocity typical of British troops on the attack. Villeroi saw Orkney’s red-coated battalions cross the supposedly impassible Petite Gette with their cavalry struggling on behind and suddenly realized that his left flank was not as impregnable as he had thought. As the British troops stormed into Offus and Autre-Eglise, driving the terrified French before them, Villeroi sent to his center for reinforcements of cavalry and infantry.

Meanwhile, on the allied left, Overkirk launched his attack. Having cleared the French garrison from Francqnée, Overkirk’s troops advanced against Taviers. Just as the Petite Gette had created swampy ground in front of Offus on the French left, so had the Mehaigne created marshlands surrounding the village of Taviers on their right. Confident that the marshes would deter any attack, the French had not extended their defenses beyond Taviers, leaving a gap between the village and the river. Into this gap Overkirk had sent the Danish cavalry, 21 squadrons strong, to help turn the French right flank. In planning these defenses, the French had not counted on the resolute courage of the Dutch Guards, who waded through the knee-deep marshes under a hail of fire to storm Taviers and drive its garrison from the village.

To retake Taviers, the French then sent in a counterattack composed of dismounted French and Swiss dragoons. While the Dutch Guards held firm in the village, the Danes charged the dismounted dragoons and successfully drove them off. Reforming their squadrons, the Danes resumed their covering position on the allied left. Overkirk, having secured Taviers, brought up his field artillery. From the village his guns began to fire on the now-exposed French right flank.

Villeroi Inexplicably Withdraws Orkney from Offus

Due to his position behind Offus, Villeroi could not see the action taking place on his right and was thus unaware of the threat to that sector. He therefore obligingly drew troops from there to reinforce his seriously threatened left flank. Just at the moment when Orkney was about to take Offus, he received a message from Marlborough ordering him to break off the attack and retire behind the Petite Gette. Orkney was both bewildered and furious over this inexplicable and seemingly insane order. Marlborough, having guessed Orkney’s reaction, sent no fewer than 10 messengers and finally his chief of staff, Lord Cadogan himself, to ensure Orkney’s compliance. Orkney was duly informed of the reason for this and stated, “I confess it vexed me to retire. However, we did it very well and in good order … Cadogan came and told me it was impossible I could be sustained by the horse if we went on then, and since my Lord could not attack everywhere, he would make the grand attack in the centre, and try to pierce there.” Marlborough then ordered the squadrons of cavalry supporting Orkney’s attack transferred from the left to the center of his line.

As Orkney fell back, Villeroi congratulated himself on having repulsed the British attack, but, still fearing for his left and unaware of the growing threat to his right, did not return the troops he had moved to that sector. While Orkney took up a defensive position, 12 Dutch and two English battalions had fought their way up and over the crest of the slope and were now forcing their way into Ramillies. Among the Dutch troops was the veteran Scots Brigade with the Duke of Argyll at its head. “Red John of the Battles” led his Scotsmen straight into an attack against the Picardy Regiment, the most senior regiment in the French Army. Thus engaged, the French in Ramillies were forced to look to their own defense and were unable to threaten Marlborough’s right flank as he now launched his main attack across the open plain on his left.

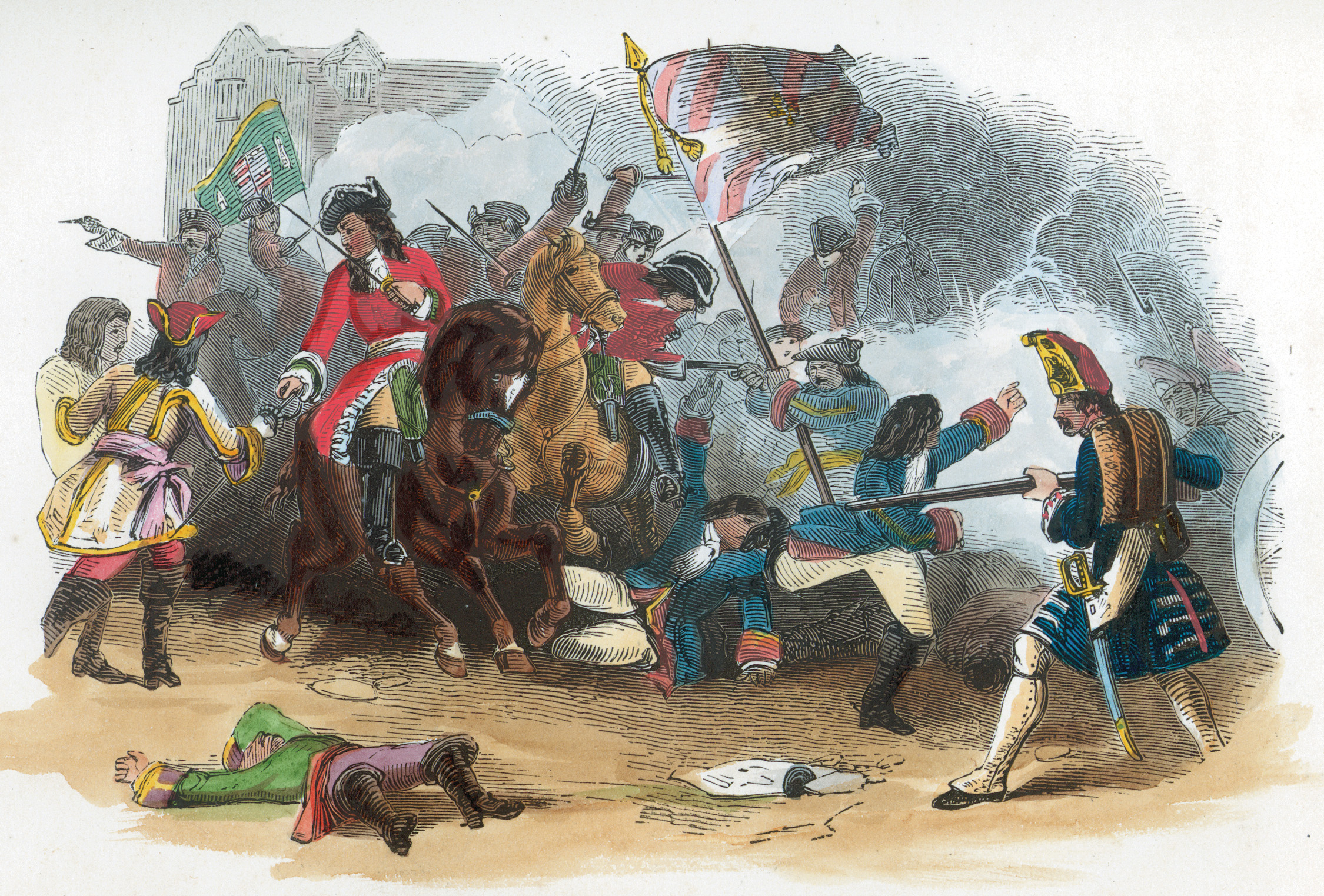

Overkirk’s Dutch cavalry, 48 squadrons strong and supported by Dutch, Swiss, and German infantry, now moved forward in one great mass that stretched from Ramillies to the Mehaigne River. They came on at a trot “in four dense lines like walls,” according to French Brigadier de la Colonie. Lumbering forward they smashed into the first line of French and Bavarian cavalry and rolled them back. As the massed Dutch squadrons pushed forward, the French infantry, interspersed between the lines of horse, stopped them cold with well-directed volley fire. Seeing the enemy halted by their infantry, the 13 squadrons of the Maison du Roi launched a counterattack. The finest cavalry in France surged forward and slammed into the Dutch, pushing them back in confusion and threatening to break completely through the allied lines. Realizing that this was a critical moment in the action, Marlborough himself led forward four battalions to shore up the line. He then rallied some of the Dutch cavalry and led them back into the battle.

As the Maison du Roi continued to bear down on the allied cavalry, they were suddenly struck in the flank by the Danish horse that had seen the enemy advance and took that moment to join the fray. The cavalry melée swayed back and forth across the plain, one huge mass of thundering hoofs and clashing sabres. Squadrons would charge, fall back, reform, and charge again. Marlborough, having placed himself at the head of 10 squadrons of the Dutch Guards, charged the Maison du Roi. Unable to withstand the assault of the French, the Dutch squadrons gave way again, taking Marlborough with them in their flight. As Marlborough attempted to leap a ditch his horse threw him and he was ridden over by the fleeing Dutch. With no horse at hand and having lost his hat and wig in the fall, Marlborough ran as fast as his heavy riding boots would allow.

The French, recognizing the duke from his scarlet uniform and light-blue sash of the Order of the Garter, attempted to run him down. A British Colonel Cranstoun who witnessed the event stated, “Major-General Murray who … was so near he could distinguish the Duke in the flight, seeing him fall, marched up in all haste with two Swiss battalions to save him and stop the enemy who were hewing all down in their way. The Duke when he got to his feet again saw Major-General Murray coming up and ran directly to get in to his battalions.” One of the duke’s aides-de-camp, Captain Molesworth, gave the duke his own horse to help him get to safety. Meanwhile, the pursuing French cavalry had charged so fast they were unable to reign up when they reached Murray’s infantry, and several of them ran onto Swiss bayonets. Marlborough’s equerry, Colonel Bringfield, then quickly brought the duke another horse. As he was holding the stirrup for the duke to mount, Bringfield was beheaded by a round shot, which reportedly passed between Marlborough’s legs as he was mounting.

The Tide Turns for the Grand Alliance

With the French attack finally blunted and the cavalry battle evolving into a massive slugging match, Marlborough continued shifting troops from his right into the attack in the center. Utilizing the rolling hills and defiles to screen his movements, the duke was able to transfer troops without the French knowing his designs. Having induced Villeroi to weaken his center, Marlborough was now strengthening his own. By this point Danish cavalry on the far left had turned the French right away from the Mehaigne River, bending it slowly back at a right angle to the center. The pressure proved too much and the Maison du Roi, attacked on both front and flank, began to buckle. Seeing this, the second line of French cavalry, composed of Bavarians and Walloons, broke and fled. His right flank being turned, Villeroi attempted to salvage the situation by pulling back and forming a new line at a right angle to the original, with Ramillies anchoring the position.

At roughly the same time that Villeroi began trying to form his new line, the Dutch troops in the allied center drove the French out of Ramillies and onto the open plain or into the marshes of the Petite Gette beyond. During the cavalry melée, “Red John” and his Scots had driven the Picardy Regiment from their positions and with the rest of the Dutch and English battalions had stormed into Ramillies. The Duke of Argyll had been the second man to enter the village and was hit three times in the attack, although not a single bullet had enough power to so much as pierce his coat. Witnessing his men fleeing from Ramillies, Villeroi faced the shocking realization that the bastion on which he planned to form his new line had fallen to the enemy. Nevertheless, he tried to keep order and establish a new line; after all, nearly half of his army had yet to be engaged. But he was too late.

By 4 pm Marlborough judged the time right to launch the final charge. He had managed to mass a superior number of troops in his center, giving him odds of roughly eight to five over the French. As the attack in the center was renewed, allied infantry continued to push the French out of Ramillies, while Danish cavalry swept around the French right flank. French Brigadier de la Colonie witnessed the allied charge: “I saw the enemy’s cavalry advance upon our people, at first at a slow pace, and then, when they thought they had gained the proper distance, they broke into a trot to gain impetus for their charge. At the same moment the Maison du Roi decided to meet them…. The enemy, profiting by their superior numbers, surged through the gaps in our squadrons and fell upon their rear, whilst their four lines attacked in front.” The French line, bent at a severe angle, finally broke, and with it went the morale of the entire army. An Irish captain in French service stated, “We had not got forty yards on our retreat when the words ‘sauve qui peut’ [save yourself] went through the great part, if not the whole army, and put all to confusion. Then might be seen whole brigades running in disorder.”

Villeroi’s attempts to form a new line crumbled, the panic having spread like wildfire and overtaken the entire army. As one man, 50 squadrons of cavalry broke and rode through their own fleeing infantry in a mad rush to escape. Marlborough saw the French breaking and gave the order for the entire line to advance. Orkney’s English battalions, having been denied their victory earlier in the day, took up the attack with redoubled fury. Villeroi tried to save his artillery, but Dutch and German cavalry overtook the long ponderous train, drove off the Spanish and Bavarian cavalry escort, and captured the lot. The duke then committed his 39 English cavalry squadrons, the least active of all his forces, to the pursuit. These relatively fresh horsemen rode down on the fleeing French like a thunderbolt and harried them for miles, taking prisoners by the hundreds. Completely demoralized, entire French units threw down their arms and surrendered en masse.

Caught up in the frantic press of fugitives swarming over the roads, Villeroi and the Elector of Bavaria were nearly captured by Marlborough’s pursuing cavalry. The Elector, in tears as he left the field, said, “The effect is so great, the terror among the troops so horrible.” By evening Villeroi’s once-confident French Army was in shambles, reduced to groups of frightened stragglers who were no longer capable of offering any kind of resistance.

Marlborough himself rode with the pursuing squadrons some 12 miles until darkness and sheer exhaustion forced him to stop. The duke had been in the saddle for nearly 28 hours and he finally lay down on the ground to sleep, sharing his cloak with Sicco Van Goslinga, a Dutch field deputy and one of his severest critics. Marlboro’s victory was complete, a triumph excelling even that of Blenheim.

For France, a Humiliating Rout

France’s Marshal Villars called Ramillies “the most shameful, humiliating and disastrous of routs.” Total French losses were between 13,000 to 15,000 killed, wounded, and taken prisoner, with an unknown number of deserters, as well as 54 of their guns lost. Of more importance was the fact that Villeroi’s army, considered the best of France’s armies, had ceased to exist as an effective fighting force. Marlborough’s losses were less than 5,000, of which 1,066 were killed and roughly 2,500 wounded. Of these, the majority were Dutch troops who had fought with excessive vigor in defense of their homeland. Later, when asked his opinion of the difference between the victories at Blenheim and Ramillies, Marlborough responded, “The first battle lasted between seven and eight hours, and we lost 12,000 men in it; whereas the second lasted not above two hours, and we lost not above 2,500 men.”

Unlike Blenheim, Marlborough’s victory at Ramillies was to prove a strategic turning point in the war. Following up the triumph at Ramillies, Marlborough proceeded to capture several major French fortresses and towns with little effort, their morale having been crushed by the news of Villeroi’s disaster. Barnett wrote that “when Marlborough eventually closed down the Ramillies campaign in October he had completed the conquest of almost the whole Spanish Netherlands; a success beyond any that Turenne or the great Conde had ever won in a single campaign in that region. Now Louis XIV’s own domains lay before his victorious sword.”

When the House of Commons received news of Marlborough’s victory they proclaimed it “so glorious and great in its consequences, and attended with such continued success … that no age can equal.” But probably the most interesting comment about the battle and its aftermath was made by the elderly Princess Palatine, Duchess of Orléans, in a letter to her aunt, the Electress of Hanover, when she wrote, “The upheavals of the last twenty years are unbelievable. The Kingdoms of England, Holland and Spain have been transformed as fast as the scenery in a theatre. When later generations come to read about our history, they will think they are reading a romance and not believe a word of it.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments