By William E. Welsh

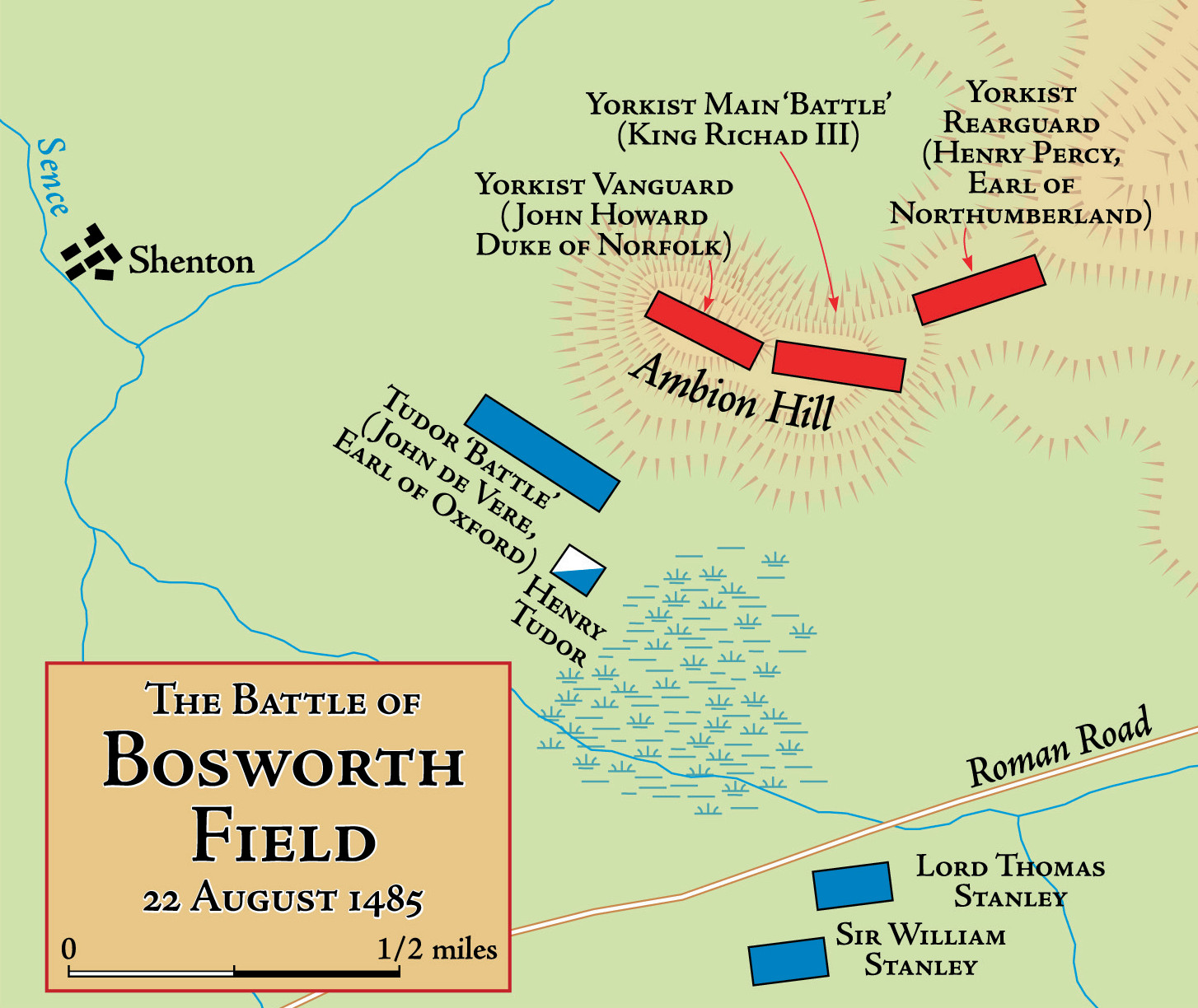

Like bees guarding their hive, the royal host of King Richard III swarmed atop 400-foot-high Ambion Hill near the Leicestershire village of Market Bosworth on the morning of August 22, 1485. Protected by low-lying marshes on three sides, the hill was a naturally formidable defensive position. Richard and his nobles formed a battle line facing southwest across the section of the hill most vulnerable to attack. The Yorkist defenders were organized into three separate battles, the contemporary equivalent of a modern division. A “dragon’s teeth” formation of primitive cannons was strewn in front of the main line, augmented by a screen of 1,500 archers spread out as far as possible in each direction to appear more threatening to the attackers. Commanding the vanguard was John Howard, Duke of Norfolk and Marshal of England, whose job it would be to meet and repel the rebel forces of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, the Welsh-born claimant to the English throne.

Behind the front line stood the cream of Richard’s army, approximately 3,000 knights, men-at-arms, and footmen, all of whom watched the enemy move into position as the morning mist burned slowly away in the valley below. They were armed with all manner of staff weapons; some even had primitive handguns. Behind them, standing with the king, impatient knights encased in plate armor from head to toe held tightly to the reins of brawny steeds that stamped and pawed the open ground. Members of Richard’s household guard held aloft the royal arms and the king’s personal standard, bearing a white boar on a red-and-blue background. Farther back was a reserve of 3,500 knights and footmen under Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland.

Henry Tudor’s outnumbered army was on the march by 7 am. From its camp at White Moors it marched east, crossed Sence Brook and a sizable marsh, and wheeled around toward Ambion Hill. Henry’s motley army comprised 5,000 troops of various nationalities and allegiances—English exiles, Welsh mountaineers, French mercenaries, and Scottish highlanders. The force was organized into one large battle under the command of John de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, a veteran commander and one of Henry’s most ardent supporters. Like Richard, Henry intended to watch the battle unfold from the rear, where his position was marked with his red dragon standard set against a background of white and green.

As the two armies closed, archers on both sides unleashed a rain of arrows that arced gracefully through the sky and plummeted down on their opponents, while the cannons at the front of the Yorkist positions blasted their Lancastrian foes. The contest was observed from a distance by another 6,000 troops under Lord Thomas Stanley and his younger brother, Sir William Stanley, whose sympathies rested with Henry—Thomas Stanley’s stepson—but who shrewdly intended to wait and see which side would prevail before joining the fray. Richard instructed Norfolk to wait until the enemy had passed the marsh and come onto firm ground before advancing. Once the Lancastrians reached the base of the hill, trumpets sounded and Norfolk’s battle strode downhill. The two sides clashed together with a tremendous roar, slashing and stabbing with long bills, swords, maces and battleaxes that crushed bones and armor. The day was young and already Bosworth Field ran red with the blood of the armies of Lancaster and York.

The grim clash marked the first time that a king and his challenger had met on the battlefield since the so-called Wars of the Roses began three decades earlier. The civil war between the Lancaster and York branches of the House of Plantagenet had been in progress for five years when Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, attempted in 1460 to wrest the throne forcibly from Henry VI, the third monarch of the House of Lancaster. As descendants of Edward III, each man had defensible claims to the throne. Although Richard had served Henry faithfully throughout much of his reign, even acting as lord protector during Henry’s frequent bouts of mental illness, the power vacuum created by the weak-minded monarch eventually led Richard to press his claim to the throne. The subsequent Act of Accord by Parliament left Henry on the throne and decreed that the York line would succeed him. The Lancastrians understandably rejected the accord and sought a more equitable solution on the battlefield. At the Battle of Wakefield on December 30, 1460, they surrounded Richard’s army and killed him and his second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland.

Richard’s eldest son, Edward, was on the Welsh border raising troops when he learned of his father’s death. He successfully repulsed an attack by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke, at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross on February 2, 1461, but suffered a temporary setback when his allies were defeated at St. Albans on February 17. However, the Lancastrian forces had so alienated and terrorized the populace that when 18-year-old Edward marched into London shortly thereafter he was hailed as a savior. He took the royal oath and was proclaimed King Edward IV on March 4. Richard, the youngest of the four Plantagenet sons, was made Duke of Gloucester. Thus began a period spanning more than two decades when the House of York controlled the throne of England, except for a brief six-month period in 1470-1471 when Henry VI was temporarily restored to the throne.

The first decade of Edward’s reign was fraught with troubles. His impulsive marriage in 1465 to Elizabeth Woodville, a Lancastrian, upset the balance of power among the peerage and alienated many of his followers. A revolt led by Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, and Edward’s own brother, George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, forced brothers Edward and Richard to flee to the continent in October 1470. On March 14 of the following year, Edward returned to retake the crown. With Richard by his side, Edward embarked on a two-month campaign in which he crushed the Lancastrians under Warwick.

King Edward’s Unexpected Death Sparks a Battle for the Throne

The young Duke of Gloucester, then 18 years old, performed ably in both battles. At Barnett on April 14, Richard drove back Warwick’s left flank, while at Tewkesbury on May 4 he held firm when the enemy launched a surprise flank attack. Barnett and Tewkesbury resulted in the deaths of Warwick and Edward of Lancaster, the Prince of Wales, respectively. For his fierce loyalty to his brother, Gloucester was handsomely rewarded. Already warden of the West Marches near Scotland, he was made Warden of the Middle and East Marches as well. On top of this, he was appointed to serve as the Constable of England. His power base was second only to his brother Edward IV.

Edward IV’s untimely death on April 9, 1483, sparked a fierce struggle for control of the throne. The king’s successor was his 12-year-old son, Edward, Prince of Wales. The new sovereign’s protector, as designated in his father’s will, was Gloucester. Away from London, both the prince and his uncle learned of Edward’s death five days later and set out immediately for London. Gloucester was suspicious of Queen Elizabeth, whose family, the Woodvilles, had increased their power and control during her husband’s 12-year reign. Fearing a Woodville-dominated monarchy in which he might be cast aside, imprisoned, or killed, Richard took swift action. Intercepting Edward V en route to London in late April, Gloucester had the young king and the trio of nobles accompanying him arrested and imprisoned. The queen took sanctuary at Westminster with her younger son, Richard Plantagenet, and her daughters. When Gloucester arrived in London on May 4, he had his young captive transferred to the Tower of London and pushed back the king’s scheduled coronation to June 22.

At some point in early June, Richard made up his mind to seize the throne. He launched a second round of arrests on June 13 during a meeting of the Royal Council in the Tower. William, Lord Hastings, the most trusted advisor of Edward IV and an ardent supporter of his young successor, was charged with plotting against the protector and summarily executed. Following this unseemly episode, Edward V’s coronation was delayed again, this time until November 9. This gave Gloucester time to build a case for usurping the throne. He enlisted clergymen sympathetic to him to declare that Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid because the king had entered into a marriage agreement with another woman before his marriage to the queen. As a result, the clergy maintained, the two princes were illegitimate and Gloucester was the rightful heir to the throne. Nine-year-old Richard joined his brother in the Tower of London.

Richard’s cause was further championed by Humphrey Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, who asserted Richard’s right to the throne and called upon the nobility assembled in London to draw up a petition asking the protector to take the crown for himself. On June 26 the signed petition was delivered to Gloucester, who was subsequently crowned King Richard III on July 6. Locked in the Tower, the princes were never seen in public again. At some point that summer they were murdered by someone loyal to Richard. (It is not clear whether Richard himself had a direct hand in their deaths, although he certainly condoned them.) Whatever his actual guilt or innocence, Richard had gained the throne, but in so doing he had sown the seeds of discord. By late 1483, the populace realized that the princes were dead and that the new king was somehow responsible for the crime.

The Woodvilles soon recovered enough to propose a marriage between Elizabeth of York, the daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, to Henry Tudor, the Earl of Richmond and the only surviving heir of the House of Lancaster. Henry’s claim to the throne traced back through his mother’s family, the Beauforts, a branch of the House of Lancaster, by virtue of Catherine Swynford’s relationship with John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, who was Edward III’s third son. Henry’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, married Edmund Tudor and gave birth to Henry in 1457 shortly after his father died of natural causes. During the unrest that followed, 14-year-old Henry was rushed to safety on the continent by his uncle, Jasper Tudor, to avoid imprisonment or death when Edward IV was restored to the throne in 1471. For the past 12 years, he and his uncle had been living in obscurity under the protection of Duke Francis of Brittany. Events moved swiftly for Henry, then in his mid-twenties, when Edward IV died in 1483. He was encouraged to claim the throne both by his strong-willed mother as well as by Henry IV’s widow, Elizabeth Woodville.

Following the disappearance of the two princes, it didn’t take long for open rebellion to break out. A pair of separate but related conspiracies was hatched in fall 1483 that threatened Richard’s fragile monarchy. One was initiated by Buckingham, and the other by prominent Lancastrians, notably Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth Woodside. The conspirators had different agendas, but they shared the common goal of wishing to dethrone Richard III. Buckingham wrote to Henry on September 24, inviting him to join forces against Richard. The uprising, known as Buckingham’s Rebellion, was hampered from the outset by a lack of leadership and coordination. Richard, who had traveled to his favorite retreat, Nottingham Castle in the Midlands, following his coronation, learned of Buckingham’s betrayal in October and took immediate steps to crush it. He galvanized loyal peers in the northern part of the realm and assembled his forces in Leicester on October 20. Norfolk secured London for the king, while Richard marched south through the seat of the rebellion, dispersing the rebels.

Buckingham went into hiding after his Welsh retainers refused to back him. He was caught on October 30 and executed several days later. Henry, who was sailing for England at the time, turned back when it appeared that he would be captured upon arrival. In the aftermath of the rebellion, parliament passed 104 bills of attainder at Richard’s request, which essentially confiscated lands and transferred titles from southern peers and gentry to his northern supporters. This, in turn, drove into Henry’s camp most of the knights and squires of the southern shires, many of whom joined Henry in Brittany.

Richard’s Spies Informed Him that Another Invasion was Imminent

After Buckingham’s unsuccessful rebellion, Henry and his supporters redoubled their efforts. Amidst a gathering of exiled English lords in a cathedral in Rennes on Christmas Day 1483, Henry formally laid claim to the throne and pledged to marry Elizabeth of York. Men and money soon began to flow to him. Among the key nobles who detested Richard and flocked to Henry’s cause was Oxford. A bitter foe of the House of York, he had succeeded to the family title in 1462 after Edward IV had his father and older brother executed for allegedly plotting against him. Henry had been living in Brittany, but when he learned that members of Duke Francis’ entourage were preparing to turn him over to Richard in 1484, he left the duchy for the court of King Charles VIII. Although he received additional funds from the French, he still lacked sufficient manpower to launch another invasion. Henry established his headquarters at Rouen in Normandy and spent the first half of 1485 corresponding with supporters in England and Wales as well as gathering ships and supplies for the high-stakes venture.

By April 1485, Richard’s spies had informed him that another invasion was imminent. The king took public action against Henry on June 21 by issuing a proclamation condemning him and his followers. The proclamation stated that Henry and the earls of Oxford and Pembroke were guilty of treasonous actions. The following day, Richard ordered a full-scale mobilization that involved dispatching troops to southern England, instructing the fleet to actively patrol the English Channel, and informing loyal peers of the realm to muster their retainers.

Richard’s power base was in northern England, and he moved his headquarters to that section of the country later that same month. Nottingham Castle was centrally located so that if Henry’s landing was successful and he penetrated the interior of the kingdom, Richard could unite with forces from other sections of his realm at nearby Leicester, a major crossroads of the Midlands, and from there pursue the invaders in strength. Whether the king would succeed against the challenger depended in large part on the loyalty of key peers of the realm. These were landholders who, under the contemporary social order known as bastard feudalism, possessed hereditary titles of nobility, such as duke and earl, and controlled the military resources of the realm. During the Wars of the Roses, the peerage figured heavily in any struggle for the crown. With their support the crown could be held; without their support the king was in serious jeopardy.

Richard could count without question on two individuals: Norfolk, who was based in East Anglia, and Sir Robert Brackenbury, the sheriff of Kent, who was in charge of the royal armory and the Tower of London garrison. Although the king also counted Lords Thomas Stanley and Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, among his supporters, they were considerably less reliable. Stanley was a veteran campaigner of the Wars of the Roses and a powerful warlord whose strength lay in Lancashire on the Irish Sea. Following the death of Edmund Tudor and her second husband, Henry Stafford, Margaret Beaufort married Stanley in 1472, the act that made him Henry Tudor’s stepfather.

Stanley had ample reason to dislike Richard. He had been imprisoned following the council meeting of June 13, 1483, at which time Hastings had been executed for treason. When Stanley requested permission to leave the king’s court in Nottingham and return to his home in Lancashire, Richard demanded that he leave behind his eldest son, George Stanley, also known as Lord Strange, as a hostage. While Richard was wary of Stanley, he still counted Northumberland among his loyal followers. The House of York had treated the Percys well during the Wars of the Roses, and before Richard was crowned king the two dukes had campaigned together in Scotland. However, Northumberland regarded Richard’s frequent presence in the north as a threat to his power base and secretly longed for his undoing.

Henry’s small fleet embarked from Harfleur at the mouth of the Seine on August 1, 1485. The fleet of ships carried 500 English and Welsh followers as well as 2,000 French and Scottish mercenaries. The ships sailed west through the English Channel away from Richard’s fleet at Portsmouth. Rounding Cornwall, the flotilla arrived opposite the rockbound coast of Pembrokeshire on August 7. Under cover of darkness, the ships slipped quietly into Milford Haven and turned into Mill Bay, the first cove on the western side of the inlet. Here, the rebel force debarked from its ships onto a small stretch of sandy shoreline.

Henry was keenly aware that his invasion force was insufficient to overthrow an enemy that heavily outnumbered him. He deliberately chose a remote location for his landing to allow him sufficient time to recruit forces from his family’s ancestral lands. He planned to march north along the Welsh coast, recruiting men from the local gentry before turning east and crossing into England at Shrewsbury, where he hoped to link up with the Stanleys. During that time, he wanted to double or triple his forces, which would allow him to meet Richard in battle on roughly equal terms. After dispatching messages to the Stanleys and to Sir Gilbert Talbot, the sheriff of Shropshire, Henry pushed north.

The response from the Welsh during the first week was disappointing. Rhys ap Thomas, the leader of a powerful Welsh family who had a large retinue and held sway over many of the southern counties of Wales, did not immediately join the army, but instead shadowed its movements as it marched north. Richard had been pressuring him to block or even stop the invaders, and Thomas put his men between Henry and Richard to make it appear to the king that he still supported him. It was a strategy that would be repeated by the Stanleys once Henry crossed the English border.

Over the course of the next week, Henry’s army would grow considerably with the addition of more fresh forces to his banner. The first of several groups to rally to Henry’s cause was that led by Thomas, who finally joined Henry after he turned east toward England. Bands of men led by other Welsh gentry and chieftains also joined the challenger before he reached the border. The new recruits more than doubled the Welsh contingent that formed the core of Henry’s army, giving Henry the confidence to attack Shrewsbury on August 15. The town surrendered after offering only feeble resistance. More good fortune followed when Gilbert Talbot with 500 English retainers and levies fell in with Henry as he pushed on toward Newport. Meanwhile, the two separate armies commanded by the Stanley brothers began gathering their forces as they marched south.

William Stanley rode down from Stone and met with Henry in Stafford on August 16. Sir William told Henry that he and his brother would not come to his aid openly until the right opportunity presented itself. Just when that moment was, Henry couldn’t say, but the Stanleys seemed to know when it would be. The armies of the two brothers were moving independently at the time, with Sir William shadowing Henry’s advance and Lord Thomas falling back before it to make it appear that he was contesting the advance. The latter was providing a valuable service to Henry, acting as a smokescreen to keep information about his position and strength from Richard’s spies. Henry had marched 150 miles in little more than a week through difficult terrain from Pembrokeshire to Shrewsbury, but it would take him nearly another full week to march the 50 miles from Shrewsbury to the battlefield over good roads. He may have deliberately slowed his march at the suggestion of the Stanleys to allow his men to rest and enable the Stanleys to maneuver into position.

King Richard Gathers His Army

More than half a week after Richard learned that Henry had landed, the king prepared to confront Richmond himself. The most likely explanation for the delay was that Richard was counting on his allies in Wales to contain Henry themselves. But the king soon learned not only that Rhys ap Thomas and others had gone over to the challenger, but also that Henry had advanced farther than he had expected and was already inside England. Cursing the leaders of Wales and Lancashire for their perfidy and vowing to turn their lands into his private hunting grounds, Richard prepared to meet Henry in battle before the size of the latter’s army grew any larger.

On August 16, Richard ordered his lieutenants to muster their forces and assemble at Leicester. Both Norfolk and Brackenbury prepared to march immediately to Leicester to join the king’s forces from Nottingham, but Northumberland and Lord Stanley dragged their feet. At the same time, Richard learned from his hostage Lord Strange, who had been caught trying to escape, that both William Stanley and Sir John Savage were planning to fight with the Lancastrians rather than the Yorkists. The king promptly branded each as traitors.

Richard left Nottingham on August 20 in battle formation and reached Leicester by sunset. Norfolk already had arrived in the town; Brackenbury and Northumberland arrived the following day. A number of other peers loyal to Richard’s cause, including the earls of Surrey, Lincoln, and Shrewsbury, also were on hand. The royal army marched out of Leicester on August 21. Norfolk led the van, while Richard marched with his troops in the middle and Northumberland brought up the rear. Richard’s destination was Atherstone, on Watling Street, the last reported position of Richmond’s army.

Henry marched south on Watling Street, a major thoroughfare built by the Romans that linked north Wales to London, arriving in Atherstone late on August 20. The following day he met again with William Stanley in a secluded location outside of the town. The younger Stanley again declined Henry’s invitation to join forces, but promised that he would confer with his brother and keep Henry apprised of their plans. Rather than continuing south, Henry turned northeast toward Leicester and marched directly toward the royal army that had mustered to meet him. Although Henry remained deeply disappointed at the Stanley’s reluctance to openly support him, his spirits were lifted when Sir John Savage and several other prominent persons entered his camp at White Moors on the eve of the battle.

Upon learning that Henry was now within striking distance, Richard left the Roman road near Sutton Cheney and ordered his army to camp on the high ground south of a large village known as Market Bosworth. Later that evening, the villagers noticed a large number of campfires in their southern fields, indicating that the royal host had arrived in force. Just west of Sutton Cheney, a high ridge of ground runs westward before dropping to level fields through which flows Sence Brooke. The high ground has been known for centuries as Ambion Hill, and at the time of the battle it was about two miles south of Market Bosworth. At the base of the hill was a large area of marshy ground fed by natural springs.

The sun rose over the landscape that would become known as the Battle of Bosworth Field shortly after 5 am on August 22. The king had not slept well, and the morning seemed to go from bad to worse. The first thing he did was ride to the top of the hill to observe whether the enemy was advancing. He found to his surprise that not only were the rebels advancing with determination on his position, but that Lord Stanley’s forces were present and doing nothing to contest the advance. Seeing this, and being sharply stung by Lord Stanley’s treachery, the king gave orders to have Lord Stanley executed at once. The order was never carried out because those responsible for doing so decided that it was more important to get ready for the coming battle. On returning to camp, Richard ordered his lieutenants to deploy their forces on the crest and southern slope of the hill. A frenzy of activity took place as the army scrambled to get into position atop Ambion Hill.

Henry awoke before daybreak. His force amounted to about 5,000 men, including his original force of 2,500 and an equal number recruited from Wales and England on the march east. Because of its small size, Henry organized his force into one battle and turned over field command to Oxford, who 14 years before had led the Lancastrian vanguard at the Battle of Barnett. The French mercenaries were led by Philbert de Chandee, the Scottish mercenaries by Bernard Stuart. Talbot and Savage commanded cavalry on the right and left flanks, respectively. Henry oversaw the advance from the rear, where he rode with a hand-picked bodyguard of nobles.

Henry drafted an eleventh-hour message to Lord Stanley inviting him to join him in the advance. Once more the elder Stanley declined the invitation, but said that he would be “at hand” with his own men ready to lend assistance if necessary. The Stanleys commanded a combined force of 5,000 to 6,000 men. William Stanley commanded a slightly larger force numbering 3,000, while Lord Stanley commanded a force ranging between 2,000 and 3,000. Most if not all of the Stanleys’ forces were arrayed just south of the Roman Road near the village of Dadlington, from which point they could join the battle at a moment’s notice.

The royal host had a difficult time deploying on the 700-yard-long ridge. It was tightly packed, with bowmen and artillery thrown forward and men-at-arms and cavalry holding in the rear. The Yorkists were arrayed in three battles: a vanguard led by Norfolk, a main body under Richard, and a rearguard entrusted to Northumberland. The force was deployed on an east-west axis, with Norfolk farthest west, Northumberland farthest east, and the king protected by both in the center. Richard’s army comprised at least 8,000 men, but may have been larger. Norfolk commanded 1,500 archers and men-at-arms, Richard commanded 3,000 dismounted men-at-arms and his household cavalry, and Northumberland commanded 3,500 men-at-arms and heavy cavalry. Brackenbury controlled the lead elements of Richard’s battle, which were interspersed with Norfolk’s vanguard at the outset of the battle.

The rank and file of Henry’s army must have been intimidated by the position of the king’s army, which substantially outnumbered them atop Ambion Hill. From where they stood in the flat plain, they could see the cannons and archers arrayed against them, backed by rows of men-at-arms clad in thick armor and billmen whose tall staff weapons glistened in the late-summer sun. When Henry’s men marched passed the swamp, the artillery opened fire on the enemy. Oxford continued marching his troops toward the Yorkists’ right flank. Once he reached his position, his bowmen prepared to fire their arrows. With a great shout, the archers on each side drew their bows, aimed at the sky and let loose their deadly missiles.

Shortly thereafter Norfolk ordered a general advance, and the Yorkist vanguard went into motion. The knights rolled downhill like an avalanche. The attack was a deliberate attempt by the Yorkists to regain the initiative from the advancing rebels. Hundreds of soldiers shouted at the top of their lungs as the two armies locked horns on the open plain. Heavily armored men-at-arms fought with swords, maces, and deadly poleaxes, while more lightly armored footmen wielded deadly bills, weapons intended to crush armor and bone alike, to slash and stab and fatally unseat riders from their horses.

“This Day I will Die a King or Win.”

To keep his army from wavering under the powerful onslaught of the Yorkists, Oxford had ordered that his soldiers were to move no more than 10 feet from the standards of their noble or chieftain. The French and Scottish mercenaries were well trained and followed the instructions to the letter. They planted their tall standards in the ground and formed tight perimeters around them. The Englishmen and Welshmen did the same. The result was that the rebels fought in tight-knit groups that were able to withstand the pressure applied by the king’s superior forces.

After an hour had passed, it became apparent to the Yorkists that the battle had reached a stalemate, and the attackers began to fall back. While some may have been genuinely frustrated with their lack of success, others may have been reluctant to die for a king for whom they had little personal regard. This would have been particularly true for those under Norfolk and Brackenbury, who were drawn from the southern shires that had risen against the king during Buckingham’s Rebellion. Whatever the explanation, the king’s impressive attack stalled completely, bringing alarm to the Yorkists and jubilation to the rebels.

Richard watched his attack unravel from the crest of Ambion Hill. As his men fell back to regroup, Oxford took advantage of the lull to rally his men in a wedge-like formation in preparation for a counterattack. It was a bold maneuver, and one that might very well win the battle for the rebels if not met by an equally decisive counterstroke on the part of the king. All the while, cavalry under Gilbert and Talbot harried the dismounted footmen and men-at-arms under Norfolk and Brackenbury. As if that weren’t enough, the Stanleys hovered close by ready to throw in their lot with the rebels and tip the scales in Henry’s favor. And where was Northumberland? The earl sulked at the rear and made no effort to support the king. His fresh cavalry not only could have checked the rebel cavalry on the flanks, but might even have ridden into the enemy rear if it had been engaged and properly led.

Accounts differ on why Richard decided to charge the enemy. Some state that Richard observed Henry riding to meet the Stanleys, while others say that he simply had no other choice if he wanted to win the battle. At any rate, a swift horse was brought to the king, and some of his closest retainers suggested he switch mounts and flee from the battlefield. The king turned down the offer and remained astride his brawny warhorse. “God forbid I yield one step,” he said. “This day I will die a king or win.”

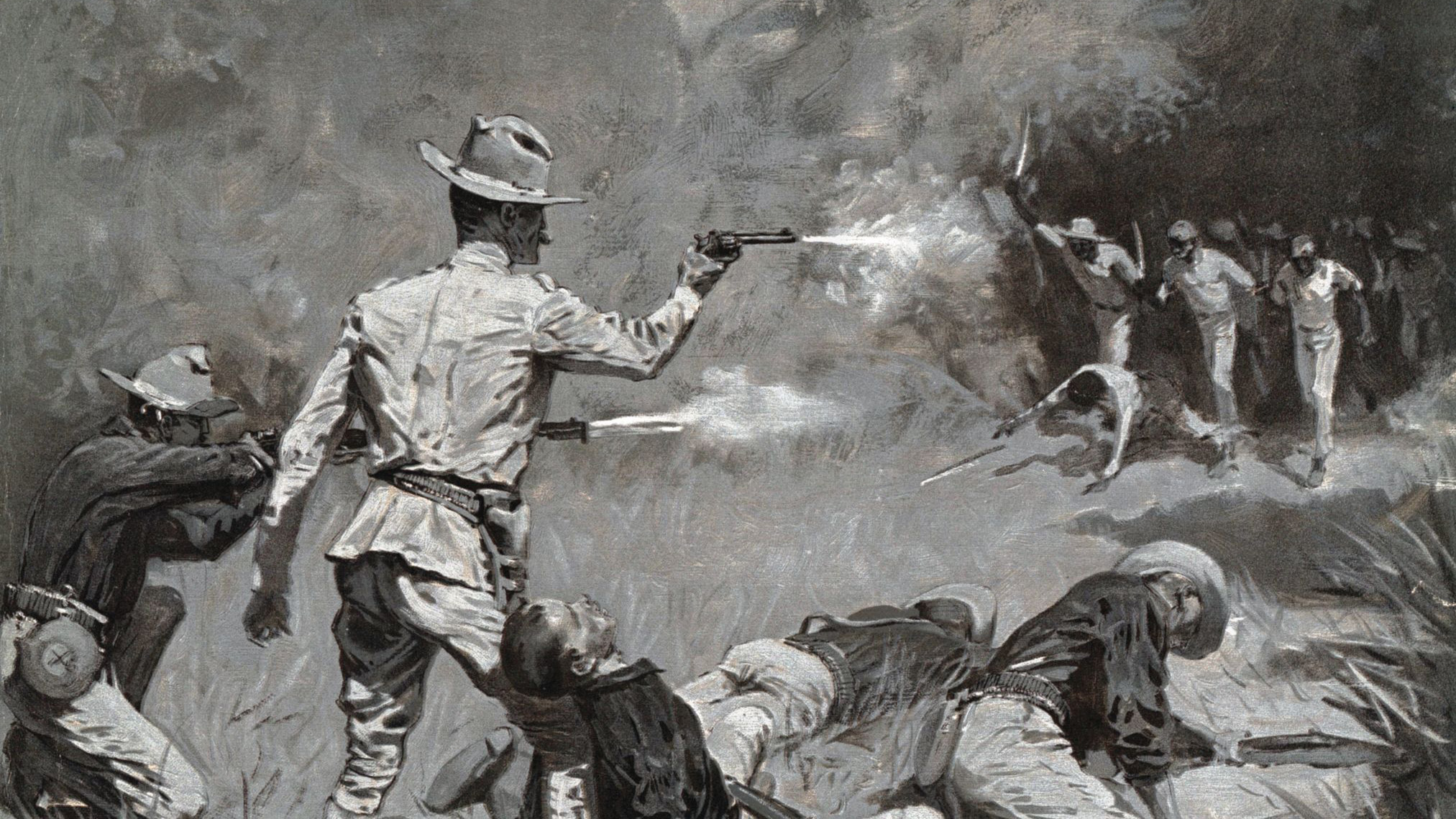

The treachery that swirled around Richard like an evil wind seemed to harden his resolve to take personal action. Leading a charge down the hill directly at Henry Tudor was a major gamble on the king’s part. If he failed, he would lose the crown and almost certainly his life. He did not hesitate. Richard put on a helmet adorned with a gold crown. Accompanied by his standard bearer, he rode to the front of the throng atop Ambion Hill and prepared to lead a grand charge, one that he hoped would result in the death of the “Welsh milksop,” as he referred to Henry. His bodyguard included a dozen titled nobles and was supported by as many as 800 horsemen. Each man in the force adjusted his helmet, checked his weapons, and followed the king downhill toward Henry and the rebels. The charge was the swan song of medieval English chivalry.

The front rank, which included the king, leveled their lances and crashed into the enemy with the screech and bang of steel against steel. Richard’s lance impaled Henry’s own standard bearer, William Brandon, who fell lifeless from his horse. The standard was quickly picked up by Welsh chieftain Rhys Fawr ap Maredudd, a fellow of enormous stature and tremendous physical strength who defended it throughout the rest of the action. Richard’s warhorse, clad in barbed armor to protect it from arrow and sword, carried him deep into the enemy ranks. The king tried in vain to hack his way toward Henry, using all his might and fighting skill. A member of Richmond’s bodyguard, Sir John Cheney, was the first to block his way. Having discarded his broken lance, Richard used his war hammer to pound Cheney from his saddle. Other nobles intervened to trade blows with the king in an effort to keep him from reaching Henry.

Even though Henry was spared a personal duel with the king, he was still caught up in the melee, and historical accounts indicate that he fought bravely that morning. He drew his sword and fought side-by-side with members of his bodyguard who managed to hold their ground in the face of the ferocious onslaught. The struggle between the two mounted commands became the center of the battle. Gradually, the Lancastrians gained the upper hand, and Richard and his retainers were pushed back, losing cohesion as a fighting force. Once again members of Richard’s bodyguard, concerned for his life, shouted to the king to flee while he still had a chance, but Richard fought on.

William Stanley, already branded a traitor by Richard, threw in his forces as soon as Richard’s charge struck the Lancastrian line. Stanley’s followers, clad in red livery denoting their allegiance to their lord, eagerly entered the fray, rushing to support Henry’s bodyguard. In twos and threes they swarmed around Richard’s knights, unhorsing them with their long bills and slashing them to pieces once they were on the ground. Richard’s standard bearer, Sir Percy Thirlwall, was one of these unfortunates. He was unhorsed and his legs were cut off by Welsh footmen wielding halberds to prevent him from raising the king’s standard. But in a superhuman effort, the legless Thirlwall continued to hold Richard’s standard aloft while the king continued fighting.

At some point, Richard’s horse became mired in the marshy ground at the base of the hill, and the king stumbled from his saddle. Now on foot, he was surrounded by Welsh footmen in the employ of the younger Stanley. Finding himself alone and outnumbered, he fought on even though there was hardly a glimmer of hope that he would survive. All around him his retainers were dying without a shred of mercy being shown them. Cut off and surrounded, Richard cried out against those who had betrayed and deserted him. In vain he sought to hold his attackers at bay. Swinging his war hammer, he shouted over and over again, “Treason!” He was eventually overpowered and struck a deadly blow by a Welsh foot soldier wielding a halberd. Once he was down, more footmen rushed forward to hack at his body with their weapons until it was horribly mutilated and his face unrecognizable.

The battle drew to a swift close once Richard was slain. It had lasted just over two hours. Many of the Yorkists attempted to flee south in the direction that the king had made his charge, but they were cut down by the victorious army, whose numbers swelled with the addition of the Stanleys. Both Norfolk and Brackenbury died in the fight, along with another 1,000 men. Lancastrian losses were much lighter. The treacherous Northumberland was taken prisoner shortly after the battle, but he was eventually allowed to go free and his lands were not taken from him. He was murdered four years later in Yorkshire by diehard supporters of Richard when he tried to collect taxes from them.

Henry retired after the battle to a hilltop near Stoke Golding, where Lord Stanley brought him the gold crown that has been knocked off the slain king’s head and found lying underneath a hawthorn bush. Richard’s mangled corpse was stripped naked, tied over a horse, and taken to Newarke, where it was displayed for two days in a church for the public to see that the king was truly dead. In appreciation for his support, Lord Stanley was made earl of Derby in October 1485 and William Stanley was made chamberlain of the royal household and chamberlain of North Wales. Nearly a decade later, Sir William would be executed for his role in another rebellion. Henry entered London on September 3 and was crowned King Henry VII on October 30. On January 18, 1486, he married Elizabeth of York, uniting the houses of York and Lancaster. The battle marked the end of the House of York and the start of a 120-year reign by the House of Tudor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments