By Mason B. Webb

After the debacle at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States realized that it had its hands full. Suddenly, America found itself faced with the worst of all military contingencies: a two-front war.

With many of its Pacific Fleet warships sunk or badly damaged, the U.S. Navy scrambled to find enough assets to take the war to the Japanese, who had been bounding from one conquest to another in the Pacific Rim since invading Manchuria in 1931.

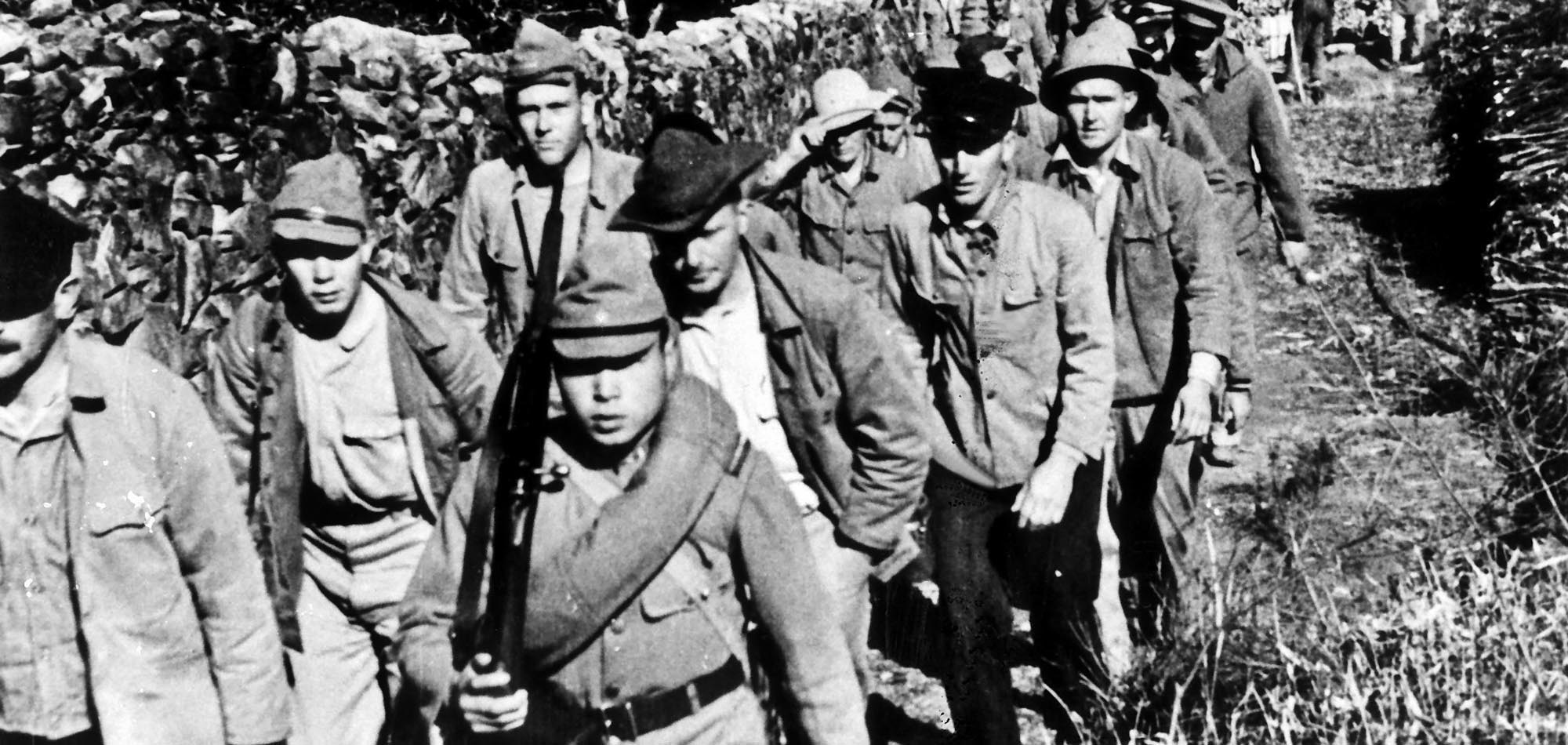

Then in late 1941 and early 1942 came more victories: the British crown colony of Hong Kong, British Malaya, Thailand, French Indochina, Singapore, the Philippines, and key oil-rich areas such as Central Java, Malang, Cepu, Sumatra, Dutch Borneo, and Dutch New Guinea in the Dutch East Indies. Soldiers who had surrendered were mercilessly executed.

A series of islands—Guam, Labuan, Wake—also fell to the Japanese. Everywhere the Imperial Japanese Army attacked seemed to crumble with great ease. But the string of unbridled successes caused Emperor Hirohito to say, “The fruits of victory are tumbling into our mouths too quickly.”

It didn’t take a strategic genius to look at a map of the Pacific and see where the Japanese invasions were heading: Australia.

A series of events then took place that shook the Japanese’s belief that they were unstoppable, invulnerable, invincible. It began with Jimmy Doolittle’s attack on Tokyo and environs, followed by the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4-8, 1942) and the Battle of Midway (June 4-7, 1942).

Doolittle’s raid by 16 B-25 bombers on April 18, 1942, was made possible because the American aircraft carrier USS Hornet had not been present at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941; in fact, no American carriers were at Pearl on that fateful day, thus sparing them from destruction and a possible even greater Japanese victory.

Next, in May 1942, the Japanese, despite numerical superiority, failed to defeat the Allies at the Battle of the Coral Sea. Third, in June 1942, they lost a four-carrier task force at the Battle of Midway, which proved to be the turning point of the war in the Pacific.

But Midway did not end Japanese dreams of further conquest. They knew that if they could hold the British Solomon Islands (which they had invaded in early 1942) lying off the eastern tip of New Guinea, they stood a good chance of invading the British colony of Australia and perhaps even knocking it out of the war. At the very least, Japanese control of the area would threaten the lines of communication between the U.S. and the east coast of Australia.

In the spring and summer of 1942, therefore, the Solomons became the next big test of wills between the United States and the Empire of Japan as each side poured resources into the area.

From August 7, 1942, until February 7, 1943, the Solomons, including the islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi, became the scene of massive air, land, and sea battles between the two warring nations.

One of the American aircraft carriers sent to the region to replace U.S. Navy losses at Midway was the USS Wasp (CV-7)—a big, hulking, behemoth of a floating island 688 feet long, with a deck that was 109 feet wide. She displaced over 19,000 long tons fully loaded, had a range of 12,000 nautical miles, and had a modest top speed of 15 knots (destroyers were twice as fast).

Her ship’s wartime complement was 2,167 officers, sailors, and Marines.

There have been seven other ships named Wasp, starting with the original, built in 1814. Except for Hornet (CV-8), she is the only ship named for an insect.

The seventh Wasp’s keel had been laid down on April 1, 1936, at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was launched on April 4, 1939, and was commissioned a year later, ready to set out on whatever the gods of war had fated for her.

Like most warships, her sailors loved her, even though she had some serious flaws in the event of war, such as virtually no hull armor that might have protected her from torpedoes.

In May 1942, Captain Forrest Sherman, who had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1917, assumed command of the Wasp.

When war broke out, Wasp was part of the Atlantic Fleet supporting the American wartime occupation of Iceland. She then joined with the British Home Fleet in April 1942 and ferried British fighter aircraft to Malta during the battles in the Mediterranean.

In June 1942, Wasp was transferred to the Pacific, where the Pacific Fleet had been reduced to three carriers (Hornet, Saratoga, and Enterprise), and prepared to provide air support for the U.S. landings on Guadalcanal.

Marine Captain Ron Van Stockum recalled, “When I was detached from Wasp at San Diego on June 25, 1942, Marine Captain John W. Kennedy Jr. relieved me as commanding officer of the Marine Detachment. In a letter to me, dated September 6, 1942, he wrote: ‘We are still afloat, and I hope we stay that way.’ His hopes were not fulfilled. Just nine days later, Wasp had disappeared beneath the sea, taking him, along with many of my former shipmates, to ‘Davy Jones’ Locker.’”

Arriving on station in the South Pacific, Wasp joined with Saratoga and Enterprise, part of the Guadalcanal invasion support force under Vice Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher. D-day was set for August 1, but the late arrival of some of the Marine transports pushed the date of invasion back to August 7, 1942.

When the battle opened, Wasp and the other carriers launched their Wildcats and Dauntlesses against Japanese targets on Tulagi, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and other islands while 10,000 Marines came ashore. Japanese aircraft that tried to intervene in the invasion were shot out of the sky. On August 7 and 8, Wasp pilots were credited with downing 15 enemy flying boats, eight floatplane fighters, and one Zero; Wasp aircraft lost totaled three Wildcats and one Dauntless scout bomber.

On August 24, Wasp was away refueling when the Battle of the Eastern Solomons broke out; she hurriedly rejoined the fleet, and her planes engaged in aerial battles. During the fighting, both Enterprise and Saratoga were damaged and had to retire for repairs, leaving Wasp and Hornet the only two carriers in the area.

On Tuesday, September 15, 1942, the carriers Wasp and Hornet and battleship North Carolina, along with 10 other warships, were escorting the transports carrying the 7th Marine Regiment to Guadalcanal as reinforcements. Wasp was operating some 150 nautical miles southeast of San Cristobal Island, and her aircraft were being refueled and rearmed for anti-submarine patrol missions.

Wasp had been at general quarters from an hour before sunrise until 10:00 am, the time when the morning search party returned to the ship. Thereafter, the ship was in Condition 2, with the air department at flight quarters. The only contact with the Japanese that day had been a four-engine flying boat that was shot down by one of Wasp’s Wildcats at 12:15 pm.

At about 2:20 pm, the carrier turned into the wind to launch eight Wildcats and 18 Dauntlesses and to recover eight Wildcats and three Dauntlesses that had been airborne since before noon.

In the September 1944 issue of Flying magazine, war correspondent Spencer Held interviewed Lt. (j.g.) Millard “Redbird” Thrash, a Wildcat pilot previously assigned to Wasp.

“The 25-year-old aviator said, ‘It was a typical South Pacific day, with brilliant sunshine and a few scattered cumulous cloud puffs. Along about mid-afternoon my flight of Grumman Wildcats took off for combat patrol over the carrier. It was an extra job for me, and my roommate was taking a nap in our stateroom when I left.’”

The eight patrolling Wildcats and three Dauntlesses had just returned to the ship before she began turning to starboard. At 2:44 pm a lookout reported “three torpedoes … three points forward of the starboard beam.”

At that moment, a spread of six Type 95 “Long Lance” torpedoes was fired at Wasp from the tubes of the B1 Type submarine I-19. Wasp put over her rudder hard to starboard to avoid the salvo, but it was too late. Three torpedoes struck in quick succession at about 2:45; one actually broached, left the water, and struck the ship slightly above the waterline. All hit in the vicinity of the ship’s gasoline tanks and magazines.

Held wrote, “Circling above the Wasp at 3,000 feet, Millard Thrash looked down on the flat-top just in time to see two enormous white spouts of water leap into the air, high above the superstructure, followed by belches of red and black flames and smoke blossoming up from amidships.

“‘Torpedoes!’ Thrash told himself, swallowing hard. “One torpedo, I learned later, hit near my stateroom, killing my roommate and about 20 others in the vicinity. I circled down with the other planes, in the hope of getting a crack at the Japs. I came down as low as 100 feet, peering vainly into the sea for just one glimpse of a sinister shadow that spelled submarine.”

Two of the spread of torpedoes passed ahead of Wasp and were observed passing astern of the cruiser Helena before the destroyer O’Brien was hit by one while maneuvering to avoid the other (structural damage from this torpedo hit would eventually lead to O’Brien’s sinking a month later).

The sixth torpedo passed either astern or under Wasp, narrowly missed the destroyer Lansdowne in Wasp’s screen at about 2:48 pm, and struck North Carolina at 2:52.

Captain Sherman slowed Wasp to 10 knots, ordering the rudder put to port to try to get the wind on the starboard bow; then, in an attempt to keep the fire forward, he went astern with right rudder until the wind was on the starboard quarter. At that point, flames made the central station unusable, and communication circuits went dead.

Held: “Lieutenant Thrash had some measure of relief when he saw the carrier make a hard left turn, and it looked as if the fires were subsiding and that the worst was over. But then another huge blast billowed up from the ship’s starboard side. I figured it was another torpedo hit but learned later that it probably was one of our own bombs, set off by blazing aviation gasoline ignited by the tin fish.”

Thrash was correct. A serious gasoline fire had broken out in the forward portion of the hangar; within 24 minutes of the initial attack, there were three additional major gasoline vapor explosions.

Aviator Mike Kernodle was at his battle station in air plot, where he directed the ship’s air operations. He heard a warning, followed immediately by a series of explosions. In his report, he wrote:

“Fixtures and equipment were torn loose and heaped on the deck, all instruments to lighting were blasted out of commission and all personnel thrown about, but no serious injuries to personnel resulted.”

After checking the ready rooms to see if all aviation personnel had moved out onto the flight deck or had gone aft, he saw a damage-control party trying to douse the fires but having no foam or water.

“Having expended all the CO2, they ran over to the port walkway just forward of number two elevator and were leading out another hose when a terrific explosion occurred apparently almost exactly underneath the midship elevator. All steel plating, expansion joint covers, barrier stanchions and plating about No. 2 elevator was blown high into the air, possibly 150 feet.

“Some of the men were also blown into the air and I did not see them again. I was thrown back from the walkway into the island doorway and landed on deck in a squatting position, for that is the position and place I found myself in after the explosion.”

Circling above, Lieutenant Thrash watched in horror the disaster unfolding below him. Held wrote, “As Wasp circled to her left, bombs deep within her continued to go off, throwing flight-deck planks, jagged chunks of steel, and sailors into the air and overboard. Thrash was greeted with an aerial view of ‘clouds of bright red fire erupting from both sides below the flight deck, billowing out 200 yards, leaving black smoke streamers and scattering little pools of fire on the water. Sprays of red, yellow, and green lights shot out like Roman candles.’”

Held also noted, “According to his shipmates, Ensign John J. Mitchell established a new world’s record for an involuntary high jump by getting himself blown 30 feet high and 60 feet away. He had been standing at a gun station about 25 to 35 feet below and 60 feet from the bridge when he spotted a white wake heading for the Wasp. A tremendous explosion, sounding to Mitchell like ‘a railroad train going up a flight of stairs,’ catapulted him into the air.

“He landed hard on his back on a platform around the bridge and broke his leg; the rest of his gun crew had been killed. ‘I guess God had his hand on my shoulder at that time. I started for the Pearly Gates, but He stopped me in midair,’ he said days later from a hospital bed.”

His boss, Lieutenant Courtney Shands, commander of Wasp’s air group, came to Mitchell’s aid and strapped the unconscious officer to a stretcher. Then Shands raced down below the flight deck to the carrier’s smoke-filled hangar, frantically digging out a life raft from one of the Wildcats; airplanes and ammunition were exploding. Shands and another officer, Lieutenant Robert Slye, placed Mitchell into the raft and carefully lowered it into the sea, where it promptly capsized.

“The sea was full of sharks which were attracted by the bloody gruel of bodies, and everybody in it was under great temptation to make tracks away from there. But Slye struggled with the raft until he righted it, pausing every now and then to thrash at the sharks with his feet.”

Held: “While this action was taking place, the rest of the escorting ships were not sitting idly by; cruisers and destroyers were lobbing out depth charges in a furious attempt to cripple whatever enemy subs had dared to inflict the damage on Wasp.”

Thrash recalled, “When a pattern of charges exploded beneath the water, the surface quivered violently, and a few seconds later several geysers rose high in the air. I saw another warship take a hit from a Jap torpedo. She shuddered but changed neither course nor speed. Another ship survived the effects of a torpedo hit without the loss of a single man and steamed cockily away for repairs so she could fight another day.”

Looking down on the Wasp from his Wildcat, Thrash estimated that about two-thirds of her crew were lined up on the flight deck, ready to abandon ship or undertake whatever other duties might be assigned. He even saw “men pushing some of our $75,000 Grummans over the side in order to localize the fire and better distribute the ship’s weight.”

Within the smoking Wasp, crewmen were doing their best to save their fellow sailors, listening for men banging on watertight doors and carrying burned and coughing men up ladders to reach fresh air.

Great, fiery blasts continued to rip through the forward part of the ship. The switchboard in the forward engine room was knocked down, the two forward auxiliary diesel generators were knocked loose from their foundations, and the forward turbo generator failed, leaving the forward part of the ship without light or power.

Aircraft on the flight and hangar decks were thrown about as if they were toys and dropped on the deck with such force that landing gears snapped. Planes in the hangar overheads fell and landed upon those on the hangar deck; fires broke out almost simultaneously in the hangar and below decks.

The water mains in the forward part of Wasp had been rendered inoperable, meaning that no water was available to fight the fire forward, and the flames continued to set off ammunition, bombs, and gasoline. The ready ammunition at the forward anti-aircraft guns on the starboard side was exploding, and fragments showered the forward part of Wasp. The number-two 1.1-inch mount was blown overboard, and the corpse of the gun captain was thrown onto the bridge, where it landed next to Captain Sherman.

As the ship listed 10–15 degrees to starboard, oil and gasoline, released from the tanks by the torpedo hit, caught fire on the water.

With the damage-control teams unable to stop the spreading flames and after consulting with his executive officer—Commander Fred C. Dickey—and Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes, commander of Task Group 61.1, who had made Wasp his flagship, Captain Sherman ordered “abandon ship” at 3:20 pm.

Many unwounded men had to abandon ship from aft because the forward fires were burning with such intensity. The departure, according to Sherman, looked “orderly,” and there was no panic. The only delays occurred when many men showed reluctance to leave until all the wounded had been taken off.

The abandonment took nearly 40 minutes, and at 4:00 pm Sherman, Dickey, and Noyes—satisfied that no one was left on deck, in the galleries, or in the hangar aft—swung over the lifeline on the fantail and slid into the sea.

Held wrote, “After two hours, with all hope gone, Captain Sherman gave the order to abandon ship, and the men, wearing life vests, either slid down lines or leaped 70 feet from the listing flight deck into the sea. Several failed to remove their steel helmets and, when they hit the water feet first, the fastened chinstraps jerked their heads backward, breaking their necks.

“Soon there were hundreds of faces dotting the ocean’s surface,” Thrash recalled seeing while circling over the ship. “They were swimming in a lake of aviation gasoline and diesel oil. As the carrier burned more fiercely … the fuel caught fire, and the inferno threatened to engulf the helpless men. It looked like half the life rafts bobbing in the water were rings of fire offering no haven to the swimmers. I feared they were doomed.’

Fortunately, the flames did not spread far from the glowing, red-hot hull, which was turned into a giant furnace by the fires raging inside.

Held wrote, “Lieutenant Courtney Shands, commander of Wasp’s air group, was floating in the water in his ‘Mae West’ life preserver and holding on to an injured man when he saw Lieutenant Ray ‘Tubby’ Conklin helping a wounded sailor down one of the lines and into the ocean. While towing a wounded man toward one of the life rafts, Shands was amazed that Conklin towed his casualty past him ‘on the double.’

The reason for Conklin’s Olympic speed? A shark was following him; the beasts had already devoured at least one man and were hunting for more.

“For more than two hours, Wasp, dead in the water, continued to burn while smaller ships moved in close to rescue the survivors. Shands recalled learning later that one badly burned officer had swum to the closest destroyer but died as soon as he was pulled aboard.

“With his carrier listing heavily to port and covered by a shroud of thick, black smoke, Thrash—and the other aviators aloft—searched for another ship on which to land. They managed to find Hornet and landed safely.

“My last view of the flat-top was blurred with tears,” Thrash admitted. “She had been my home for eight months, and I was strongly attached to her. Scores of the boys aboard were my pals.”

Despite the ever-present danger of submarines, the cruisers Helena and Salt Lake City and the destroyers Lansdowne, Laffey, Farenholt, Lardner, and Duncan patrolled through the flaming waters around Wasp and picked up 1,946 survivors.

As night began to fall, the fires worked their way aft, consuming the flight deck and bridge; four more violent explosions boomed. Of her ship’s company, a Marine detachment and an embarked air group—25 officers and 150 men—were killed or missing, and 366 were wounded. In addition, 28-year-old Jack Singer, an International News Service war correspondent, also died in the disaster. A Liberty ship was later named in his honor.

When he learned of Singer’s death, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox paid tribute to the gallantry and perseverance of the American war correspondent. “I think we all feel a great sense of pride at the long chance men are taking to get the news,” Knox stated. “It is very admirable and creditable to the profession.”

All but one of Wasp’s 26 airborne aircraft were able to land safely on the carrier Hornet nearby before Wasp sank, but 45 aircraft went down with the ship.

Captain Sherman wrote: “By about 1515 [3:15 pm] the fire had spread through the forward half of the ship and was burning fiercely. It had become necessary to evacuate the interior of the island. Numerous casualties were being inflicted by exploding ammunition and by the fire.

“The reports received from below and the results witnessed on deck showed that efforts to combat the fire were futile due to lack of water. Efforts to couple hoses together and get water from aft had not been effective because lack of water pressure. The main engines had been able to meet the initial demands made upon them and the stern was still tenable except for the hazards from flying fragments.

“The fire was completely out of control and was working steadily aft. After receiving reports from both the Air Officer [Kernodle] and the Air Group Commander who had just returned from the hangar deck, and after consultation with the Executive Officer, I reluctantly decided that the ship could not be saved and that men must be gotten off promptly if unnecessarily heavy loss of life were not to be incurred. After consulting with the Task Force Commander [Noyes], and with his approval, about 1520 [3:20 pm] I issued orders to abandon ship.”

At the fantail, a small group of about seven or eight officers and men gathered around Captain Sherman. Chaplain Williams recalled, “We reported to the Captain that the wounded were evacuated and the men over the side.”

Sherman calmly replied, ‘Thank you. Well, gentlemen, it is time to leave.’”

Sherman’s own after-action report says, “All injured men were gotten onto rafts or rubber boats. All the occupants of the sick bay were cared for and all were rescued. Rafts and float nets were used as far as possible, but the fire in the ship and on the water forward required most men to leave from aft with life preservers only, or with mattresses or other substitutes …

“About 1600 [4:00 pm] I lowered myself into the water. At this time the list to starboard was increasing steadily. While swimming away from the ship I observed the fire working aft in the hangar and on deck, the list increasing, and continued explosions.”

Wasp was still burning fiercely and dead in the water. She could not be left in that state, so the decision was made to scuttle her. Lansdowne was selected to administer the coup de grace and fired five torpedoes into the dying ship’s gutted hull. The first two torpedoes were fired perfectly, but did not explode, leaving Lansdowne with only three more.

The magnetic-influence detonators on these were disabled and the depth set at 10 feet. These next three tin fish exploded, but Wasp remained defiantly afloat. By now, the orange flames had enveloped the stern, and the carrier floated in a burning pool of gasoline and oil. She sank by the bow at 9:00 pm.

In Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Ira Wolfert’s words, “The Wasp died a lingering death, burning for hours with vast, blazing spewings that looked like the mouth of war itself opened wide … In the end, United States destroyers reluctantly had to give the coup de grace with torpedoes.”

In the wake of Wasp’s loss, Captain Sherman praised the commanding officers of the five destroyers that rescued his men. “Their task,” Sherman wrote, “required the nicest judgment in seamanship and required that their ships be stopped for considerable periods while many seriously wounded casualties were laboriously taken aboard. The limited facilities of the Duncan and Lansdowne in particular were stretched almost to the breaking point in an attempt to support life in the gravely wounded and to make all others as comfortable as possible during the passage to port.”

The loss of Wasp left Hornet the only U.S. aircraft carrier in the Pacific; Hornet was herself sunk during the Battle of Santa Cruz on October 26, 1942. Fortunately, American shipyards, working around the clock, were already turning out more carriers that would take the place of those that had gone to the ocean’s floor in a blaze of glory.

Epilogue

In 1949, Admiral Forrest P. Sherman became Chief of Naval Operations, at that time the youngest man to serve as head of the Navy. Nearly two years later, while on a military and diplomatic trip to Europe, he died in Naples, Italy, of a heart attack at age 54.

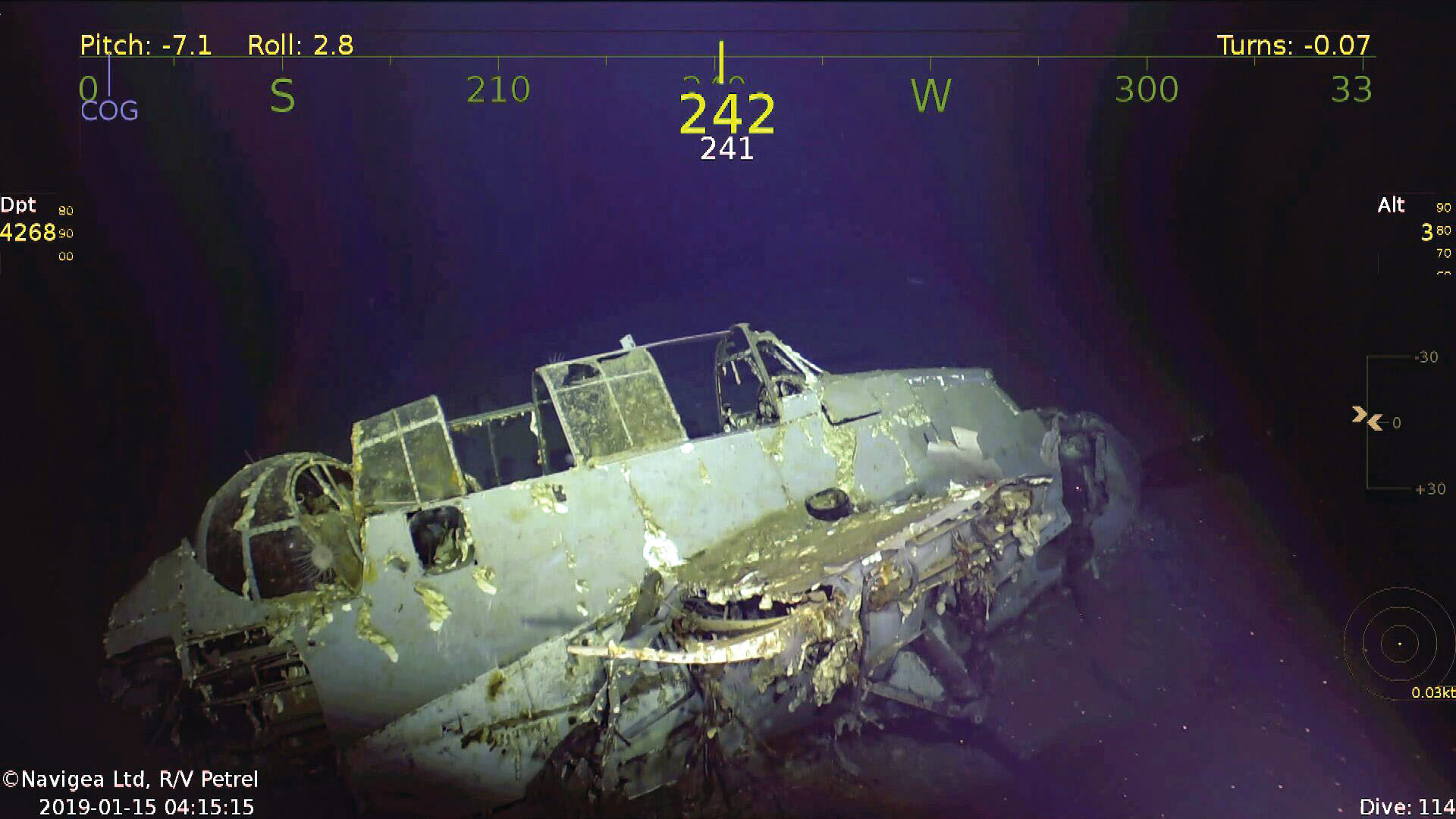

For 77 years the burned and blasted hulk of the Wasp lay undisturbed in her watery grave 350 miles southeast of Guadalcanal. Then, in the early morning hours of January 14, 2019, researchers laid eyes on her.

According to the New York Times, “Aboard a 250-foot-long research vessel called the Petrel, originally built for servicing oil fields, a group of explorers, historians, divers and submersible pilots have been combing the South Pacific for the graves of American warships like the Wasp since 2017.

“Funded by Paul Allen, a co-founder of Microsoft who died in October 2018 and who wanted to find these ships as a way to honor his father’s military service in World War II, the ship’s state-of-the-art technology allows for faster and more efficient searches than were possible even a decade ago.”

The Navy has no intention to touch the wreck at all. Its interest is in studying the Wasp and other wrecks the Petrel has found, in part to assess the damage the ships suffered and to see what lessons can be applied to how the service builds ships in the future.

“The Wasp is sitting upright on the bottom of the Pacific, in pretty deep mud,” says Sam Cox, a retired admiral who heads the Navy’s historical department. “The mud actually comes up to about where the water line was, so you can’t see where the actual torpedoes hit.”

[Allen’s crew also found the carrier Hornet while on the same trip, resting on the bottom about 400 miles northeast of Guadalcanal, and the USS Indianapolis in August 2017.]

The final picture is an Avenger, not a Dauntless.