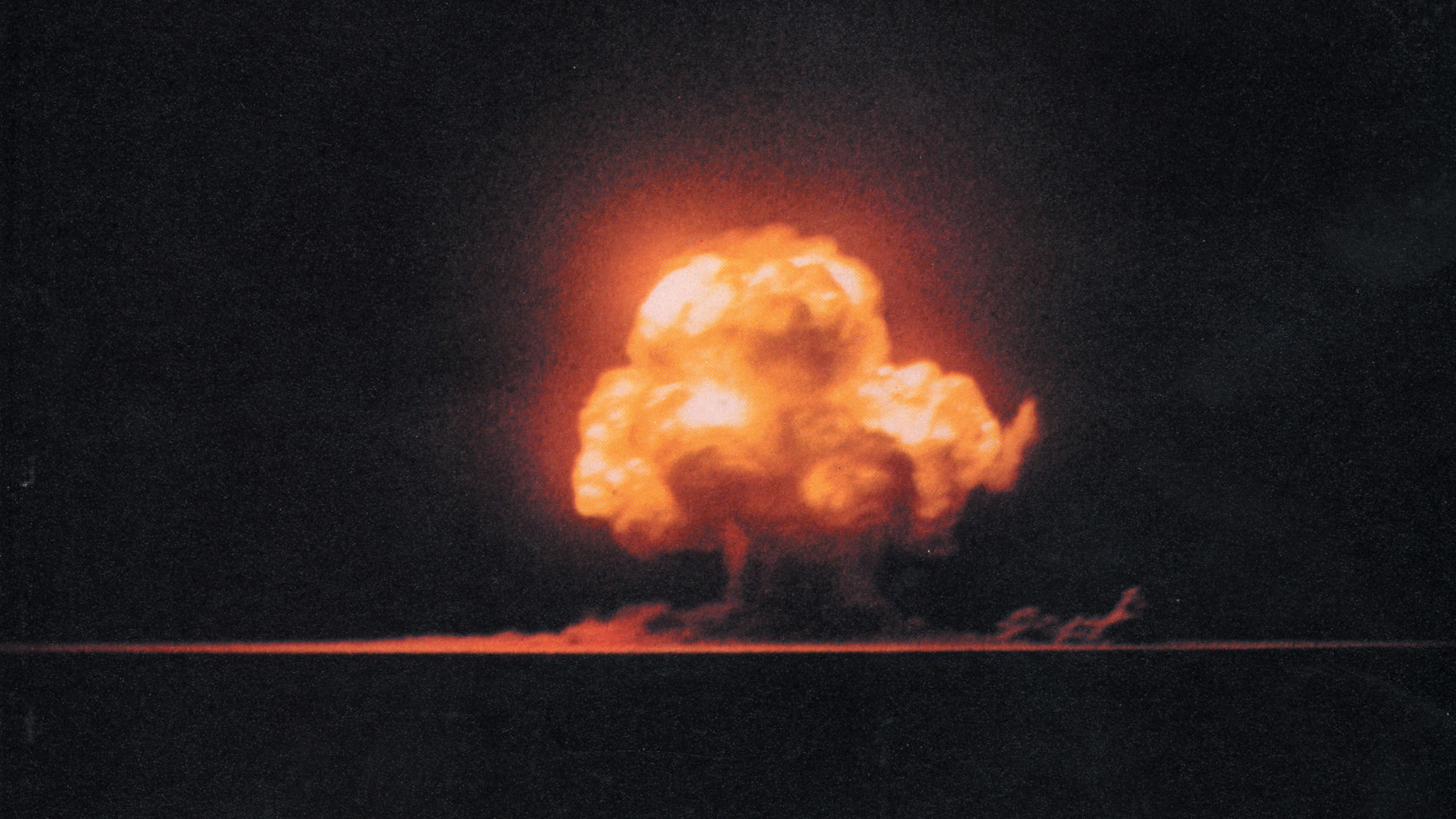

When Colonel Paul Tibbets and his crew departed their base on the island of Tinian in the Marianas on the morning of August 6, 1945, their Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber carried with it a weapon that would change the world. Christened Enola Gay by the pilot, in honor of his mother, the plane was to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Tibbets saw the mission as his duty. In his eyes, it was that basic. In a flash, an estimated 80,000 people died. Thousands more would perish later from the effects of radiation.

“If Dante had been on the plane with us, he would have been terrified,” the pilot said in a 2005 interview with reporter Mike Harden of the Columbus Dispatch. “At the 60th anniversary, Tibbets said of his notoriety, ‘It’s kind of getting old, but then so am I.’ He waved off other requests to be interviewed, in part because of his health and for weariness of suffering a new crop of reporters thinking they are the first to ask, ‘Any regrets?’ His answer always has been a resounding ‘Hell, no,’ lately modified to lament, ‘The guys who appreciated that I saved their asses are mostly dead now.’ He is, today, a man untroubled with the certainty of joining their ranks … As soon as the death certificate is signed, I want to be cremated. I don’t want a funeral. I don’t want to be eulogized. I don’t want any monuments or plaques.’”

During a 1970s interview, Tibbets stated bluntly, “I’m not proud that I killed 80,000 people, but I’m proud that I was able to start with nothing, plan it and have it work as perfectly as it did. I sleep clearly every night.”

After more than 60 years of asserting that he had no regrets about the nature of the mission, the loss of life, or his place in history, Paul Tibbets passed away at his home in Columbus, Ohio, on November 1, 2007. He was 92 years old. Requesting that there be no headstone to mark a final resting place because he did not want protesters to have a focal point for their political agendas, Tibbets instead asked to have his ashes scattered over the waters of the English Channel.

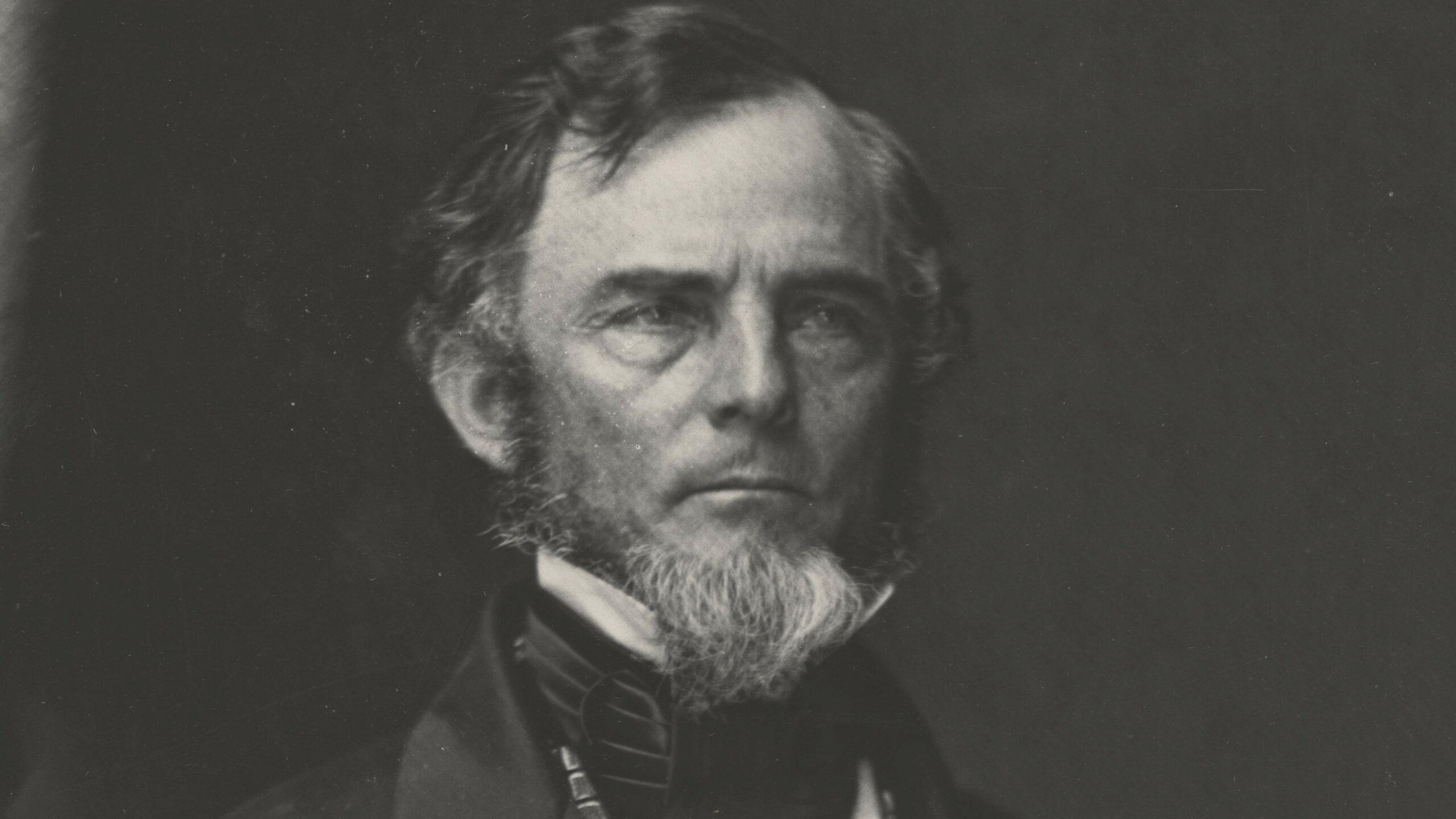

Perhaps, as much as anyone, Tibbets is an example of a military man who carried out his orders. Prior to his selection for the atomic bomb mission, he had already distinguished himself as a leader and combat pilot. On August 17, 1942, he flew the lead bomber in the first mission of the U.S. Eighth Air Force against a target on the continent of Europe. He also flew missions in the Mediterranean Theater and was a test pilot during the development of the B-29. After the war, he remained in the Air Force until 1966 and retired with the rank of brigadier general. He served as military attaché in India and later with Columbus-based Executive Jet Aviation Company.

Those who served with Tibbets remembered him as well-respected, tough, and one of the most capable pilots in the Army Air Forces. He was also a man of character when it came to weathering the storm of controversy that followed him for the rest of his life after Hiroshima. Several salient points must be considered. First, Tibbets was in the military and did as he was ordered. Second, the decision to drop the atomic bomb rested with President Harry Truman, not with Tibbets. Third, there is no question that an invasion of Japan would have been far more costly in lives, both Japanese and American, than the casualties suffered as a result of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. Many of those who read these lines would, in fact, not be here today had their fathers died during an invasion of Japan.

It is indeed a tragedy that lives, civilian or military, are lost in war. However, such is the nature of armed conflict. As General William T. Sherman so aptly stated, “War is hell, and you cannot refine it.”

Since that fateful mission was executed in 1945, the political, philosophical, and moral debate over the atomic bomb, and the role of Paul Tibbets in its delivery, has continued. Undoubtedly, it will continue long into the future.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments