By Peter Kross

For 13 tension-filled days in October 1962, the world came closer to nuclear war than it has ever come before or since. People hesitantly went about their daily lives, not knowing if they or their children would wake up the next morning. In Washington and Moscow, the key players in the unfolding drama,

President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, engaged in a dangerous game of cat and mouse, trying desperately to keep the genie of nuclear war in its bottle before it escaped in a fatal puff of smoke.

At the heart of the matter lay Cuba, the communist-controlled island 90 miles from the Florida shores. When Fidel Castro came to power in the 1959 revolt that ousted corrupt leader Fulgencio Batista, the Eisenhower administration decided that it was worth a try to cooperate with the bearded upstart. Soon, however, that policy was discarded after Castro deemed it more prudent to turn to the Soviet Union for military assistance. In March 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower tasked the CIA with planning an operation that included “a paramilitary force outside of Cuba for future guerrilla actions.” That summer, the CIA constructed a secret training base in Guatemala for Cuban exiles. In other measures designed to destabilize Cuba, the United States introduced economic sanctions, slashing the amount of sugar imported from Cuba and cutting all diplomatic ties between the two countries.

JFK and the JMWAVE

Cuba became a hot topic in the 1960 presidential election between Vice President Richard Nixon and Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy. Nixon was the point man in the administration’s secret efforts to oust Castro, and on the campaign trail Kennedy attacked both Nixon and Eisenhower for not doing enough to oust Castro. Nixon could not fight back, since he needed to protect the secret initiatives then going on behind the scenes to disrupt the Castro regime. When Kennedy won the election, the plan for the exile invasion of Cuba was well on its way to completion; the new president reluctantly agreed to proceed with the invasion. It turned out to be a military and political disaster for Kennedy. The exiles were soundly defeated by Castro’s far superior military at the ill-starred Bay of Pigs invasion, and it took another year before all the surviving prisoners were finally released from Cuban jails.

The failure at the Bay of Pigs was a turning point in the Kennedy administration’s attitude toward Cuba and the Castro regime. Cuba now became the president’s number one international priority, and the defeat of the CIA-backed rebels only hardened policy makers in Washington as to what future steps to take to rid the hemisphere of Castro. What followed was a secret war against Castro, designated Operation Mongoose, run entirely by the CIA—the largest covert war in the agency’s history. The man in charge was the president’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

On August 23, 1962, senior presidential adviser McGeorge Bundy issued National Security Action Memorandum 181, ordered by JFK, to implement a covert operation and propaganda war to topple Castro. The CIA set up headquarters in Miami and dubbed the new operation JMWAVE. Working out of an abandoned site on the University of Miami campus, JMWAVE would become the most elaborate paramilitary operation since the creation of the CIA in 1947. Some 400 CIA agents, sub-agents, and assorted hangers-on began plotting the fall of Fidel Castro. On January 19, 1962, Robert Kennedy held a meeting of the top members of the Mongoose team to plot strategy, informing them that “a solution to the Cuban problem today carries the top priority in the United States government—all else is secondary—no time, money, effort, nor manpower is to be spared.”

Operation Anadyr

Meanwhile, in Moscow, Nikita Khrushchev watched with growing alarm the actions the United States was taking toward Cuba. Under his aegis, the Russians poured military and technical advisers into Cuba to prevent another U.S.-sponsored invasion of the island. In July 1962, a Cuban delegation headed by Raul Castro (Fidel’s brother) arrived in Moscow for high-level talks about the shipment of military supplies to Cuba, including nuclear missiles. During the meetings, Raul Castro signed a draft treaty with the Soviets that led to the deployment of Russian military forces to Cuba.

The codename for the operation was Anadyr, named for the river that flowed into the Bering Sea. The Russian general staff wanted to fool Western intelligence into thinking that the operation was designed to take place in the far north of the USSR, and troops were given cold-weather clothing even though they were destined for warm, sunny Cuba. The initial group of Soviet military men arrived by air in Cuba on July 10 and were soon joined by 67 others, who were given cover identities as machine operators and irrigation and agricultural specialists.

Over the summer, the first Soviet ships departed from ports along the Black Sea. Nuclear missiles were stored in specially constructed packing crates, and the ships were equipped with metal shields that could protect them from aerial photography. The ships’ captains were given sealed envelopes and were told to open them at a certain point in the Atlantic Ocean. When they reached that destination, a KGB officer on board each ship was on hand to determine the precise location. Soon, a total of 85 ships began the long voyage across the sea to Cuba, along with Soviet troops who would man the missile sites. The size of the ongoing convoys did not go unnoticed. American intelligence assets monitored the large fleet of merchant ships heading for Cuba. However, no one in the intelligence community knew what the convoys contained or their true purpose.

Operation Anadyr consisted of medium-range R-12 missiles (NATO designation SS-4) and long-range R-14 missiles (designated by NATO as SS-5) to be placed at various sites around Cuba. In total, 36 nuclear warheads were on site to be placed on top of the missiles as needed. These missiles could reach all of the United States with the exception of the Pacific Northwest. The missiles in Cuba were under the ultimate control of Khrushchev, but he gave General Issa Pilyev, permission to use the nine Luna missiles for the defense of Cuba if the United States invaded the island. The Soviets stationed 43,000 troops in Cuba under the strictest secrecy. The soldiers wore civilian clothes to blend into the local population

Phillippe de Vosjoli’s Warning

In July 1962, Phillippe de Vosjoli, the Washington station chief for the French intelligence service, arrived in Cuba. He would later write: “My reports started mentioning the arrival of Soviet ships in Havana and, strangely, in Mariel, a small harbor seldom appearing on the maps of Cuba. Other ships were landing people and cargos in harbors where the Soviet flag had, until now, been a rarity. Soldiers were reported guarding a cavern where work was being conducted secretly. Photographs taken by an agent showed that a large hole was drilled through the ceiling of the cavern to the pasture 50 feet above. This hole had the appearance of a large tube, big enough to hold a missile and oriented in the direction of the United States.”

After leaving Cuba, de Vosjoli returned to Washington, where he met with CIA Director John McCone to brief him on his trip. McCone, a Republican, had replaced Allan Dulles, who was fired after the Bay of Pigs fiasco. McCone had no previous intelligence experience but ironically had served as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. Following his meeting with de Vosjoli, McCone took immediate steps to coordinate all available intelligence about the Russian ships en route to Cuba. After reading all the reports, he came to the conclusion that the Russians were shipping strategic nuclear missiles to Cuba and began alerting the other government departments about his hunch. A National Security Council meeting took place on August 22 in which the president was informed of McCone’s thesis. The president did not believe that Khrushchev would be stupid enough to make such a risky move, but he ordered the Defense Department to draw up a contingency plan to deal with any placement of Russian nuclear missiles in Cuba.

U-2 Surveillance Missions Over Cuba

McCone left Washington for his honeymoon that summer. His deputy, General Marshall Carter, served as McCone’s stand-in. A U-2 surveillance mission on August 29 showed unmistakable evidence of surface-to-air (SAM) millsile sites that were being built at a fever pitch. The U-2 also found evidence of a cruise missile site in eastern Cuba and missile patrol boats in various Cuban ports.

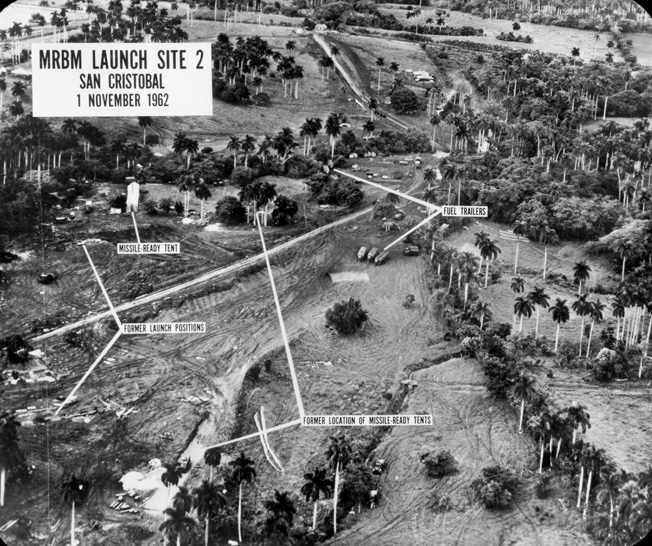

On Sunday, October 14, a U-2 took pictures over the San Cristobal area, and the pictures were developed by the National Photo Interpretation Center the next day. What the analysts found was nothing short of sensational—equipment associated with Soviet Medium Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBM), military barracks, missile shelter tents, missile erectors, and missile launchers. A second site with the same configuration was located close by. The situation had changed dramatically. The Russians now had missiles that could strike the entire United States within minutes.

On October 16, Ray Cline of the CIA and Art Lundahl, one of the photo interpreters of the U-2 flight over Cuba, took the startling pictures to McGeorge Bundy and Robert Kennedy. They then met with President Kennedy and explained what the photos contained. The president picked a group of his most trusted advisers to meet and decide strategy. The secret team was dubbed EXCOMM, or the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. The members of EXCOMM were the president, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Robert Kennedy, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, General Maxwell Taylor, UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, Ambassador to Russia Llewellyn Thompson, presidential aide Ted Sorensen, and others. The EXCOMM members discussed all sorts of military and political options, including an immediate air strike on the missile bases, an invasion of Cuba, or taking the matter to the United Nations. Later, when the discussion turned to a possible air strike against Cuba, Robert Kennedy said, “I now know how Tojo felt when he was planning Pearl Harbor.”

The Naval Blockade of Cuba: An Alternative to Invasion

The U.S. Navy had already planned a large-scale military exercise that was scheduled to take place in the Caribbean near Cuba. An amphibious task force that included 40,000 Marines, plus the 5,000 more stationed at the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay, as well as the Army’s 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions began to move into place. Soon, some 100,000 troops were waiting at bases in Florida for the signal to invade Cuba if necessary. In the days ahead, some 14,000 additional Air Force reservists were called up for emergency duty, a majority of whom would fly the transport planes if an airborne drop became necessary.

The Pentagon began an intensive review of how best to use its military resources if war was necessary. A surgical strike to take out the nuclear missile bases would not remove all the missiles and would still leave Russian bombers and torpedo boats untouched. Such a strike would kill hundreds of Soviet soldiers, thus risking nuclear retaliation by the Soviets.

In the EXCOMM meetings, an alternative course of action was brought up—a naval blockade of Cuba. A blockade was technically an act of war, but it was the middle ground between doing nothing and an all-out war. The blockade, in itself, would not remove the missiles from Cuba, but it would give the United States more time to finalize plans. The blockade proposal was hotly debated for several days, and when a vote was taken 11 members favored the blockade (now called a quarantine), and six wanted an air strike. The Navy sent aircraft carriers and other line ships in an arc of 800 miles outside Cuba to enforce the quarantine. More U-2 photo reconnaissance flights roamed over Cuba and discovered that the development of the missile sites was almost completed, as well as the fitting out of the IL-28 Beagle light bombers that had been placed in Cuba.

![ST-A26-16-62 29 October 1962 National Security Council Executive Committee (EXCOMM) Meeting, 10:10AM [Scratching in center of negative. White spotting throughout negative. Black line in upper left corner of negative.] Please credit "Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston."](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/m-Intel6.jpg)

As if tensions were not high enough, an incident almost led to all-out war. On October 27, Major Rudolf Anderson piloted a U-2 over Cuba on a reconnaissance run. While flying over the eastern tip of the island, his plane was hit by an SA-2 missile, and he was killed. In Washington, there were immediate calls for a retaliatory strike against the missile site responsible for the shoot-down. However, JFK, despite intense pressure from the joint chiefs, refused to attack the site, asking that cooler heads prevail, at least for the moment.

Two days before the incident, the Kennedy administration took its case against the Soviet Union to the General Assembly of the United Nations. Stevenson came armed with slides of the missile sites being constructed in Cuba. The presiding member of the General Assembly at that time was Russian Ambassador Valerian Zorin, who denied that any missiles were in Cuba. In a dramatic confrontation carried live on television, Stevenson asked Zorin if he could prove the missiles were not in Cuba. Zorin replied, “I am not in an American courtroom, sir, and I do not wish to answer a question put to me in the manner in which a prosecutor does.” Stevenson shot back: “You are in the courtroom of world opinion right now, and you can answer yes or no. You have denied that they exist, and I want to know if I have understood you correctly.” Zorin said, “You will receive your answer in due course.” Stevenson replied, “I am prepared to wait until hell freezes over, if that is your decision.”

Defusing the Crisis

Even after the quarantine on Cuba was established, the president wanted to defuse the situation, looking for a diplomatic end to the crisis. There was talk of swapping the obsolete Jupiter missiles the United States had placed in Turkey in 1958 for the removal of the Soviet missiles in Cuba. On October 27, Robert Kennedy met with Soviet Ambassador Antonin Dobrynin to discuss the crisis. RFK told Dobrynin that the president considered Khrushchev’s proposal to remove the missiles from Cuba in return for an American pledge not to invade the island “as a suitable basis for regulating the entire Cuban affair.” If the missiles were removed, the United States would end the quarantine against Cuba and remove its missiles from Turkey at an appropriate time in the future.

The president, in fact, had received two letters from Khrushchev (the first one being conciliatory, the second more belligerent in tone), stipulating that if the United States promised to withdraw its missiles from Turkey, the Soviet Union would remove its offensive missiles from Cuba. Ambassador Thompson, who knew Khrushchev well, advised the president to respond to the first message—the second was probably written under pressure from the Soviet military. JFK agreed, responding in similar conciliatory fashion. Dobrynin cabled Moscow with Kennedy’s assurances on the Jupiter bases, and the Russian leader sent Kennedy a private message agreeing to Kennedy’s proposals. Russian missiles would be crated and sent home accordingly. The American naval blockade ended officially at 6:45 pm on November 20, 1962. The crisis was over.

Historians still debate which side blinked first in the nuclear standoff, an academic exercise made possible by the peaceable settlement of the world’s most dangerous international crisis. In their separate ways, both Kennedy and Khrushchev were heroes, although neither would have long to enjoy his achievements. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas exactly one year and two days after the naval blockade ended, and Khrushchev was ousted in a bloodless political coup in 1964.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments