By Roy Morris, Jr.

The CSS Alabama went to her watery grave on June 19, 1864, off the coast of France, but the lingering effects of her wartime successes made naval history: she continued to haunt the American and British governments for years to come, embroiling the two English-speaking nations in a legal test of wills that would last well into the next decade.

Almost from the day she was launched at the Laird Shipyards in Liverpool, England, in May 1862, Alabama was a cause of friction between the two countries.

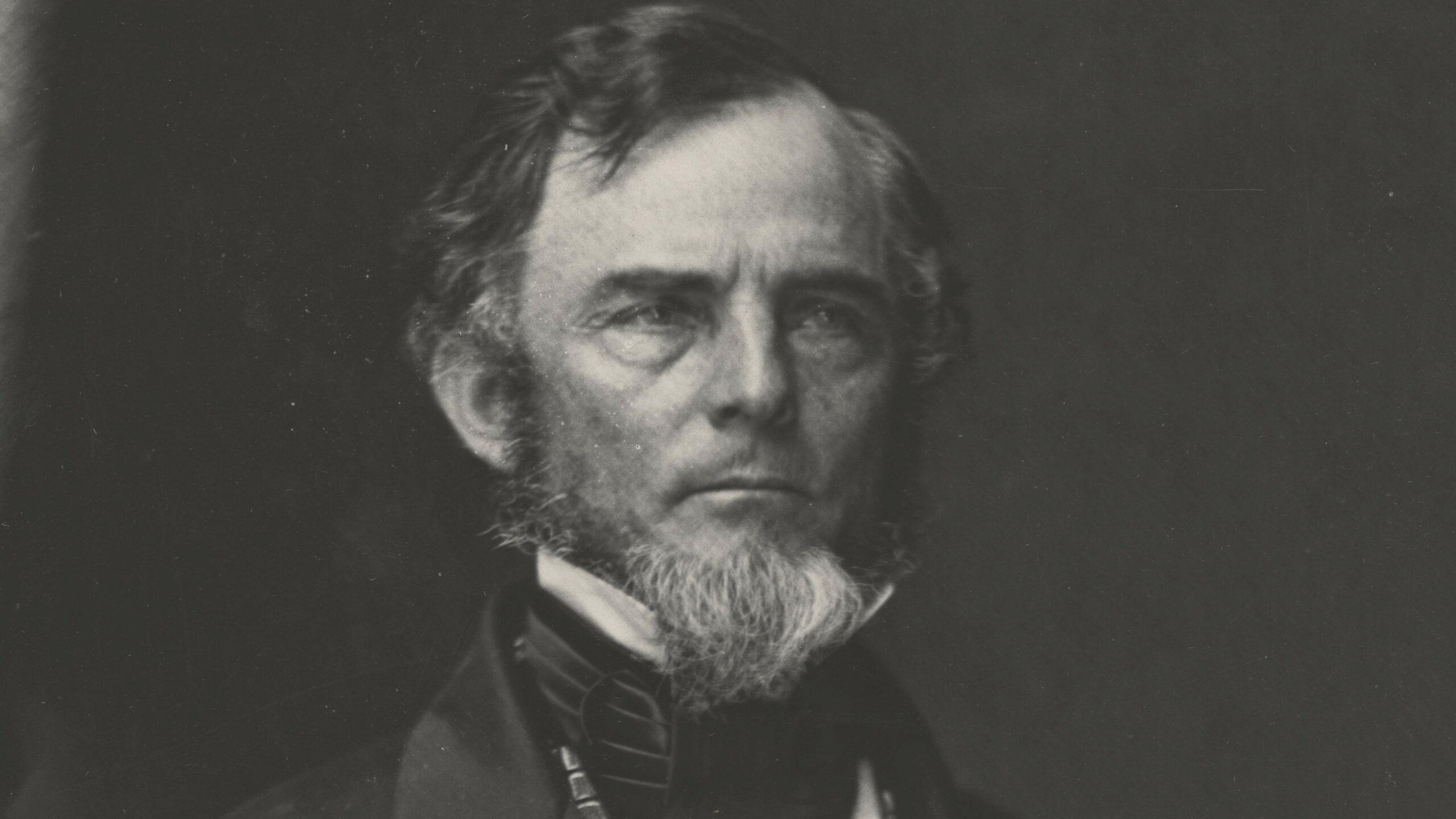

U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain Charles Francis Adams complained long and loudly to his British counterpart, Lord John Russell, about England’s practice of building and selling warships to the Confederacy. In particular, Adams was incensed by the clumsy subterfuge used to build and transport Alabama from Liverpool to Terceira in the Azores. The ship left Liverpool on July 29, 1862, on what was supposed to be trial run around the harbor.

Instead, it became the ship’s maiden voyage, and visitors aboard the vessel were dispatched back to shore while the steamer set a course southwest to the Azores, where Confederate Captain Raphael Semmes and his crew were waiting to take possession.

Tyrant of the Seas

Eventually, Adams’s protests were effective in curtailing the amount of shipbuilding done by English interests during the latter stages of the Civil War, but the complaints came too late to stop Alabama. For the next 22 months, the sleek Confederate raider literally sailed the seven seas, disrupting Federal shipping around the globe, from the Gulf Coast of Texas to the Indian Ocean. Alabama captured more than 60 vessels and inflicted some $6.5million in material damages.

The U.S. government, through Secretary of State William Seward, demanded more than $19 million in damages and reparations from the British for the losses inflicted by Alabama and her fellow raiders Shenandoah and Florida. The claims met with a magisterial silence from Great Britain. Sumner demanded exorbitant reparations from the British, including the ridiculous demand that Britain surrender all her holdings in North America, including Canada.

The “Alabama Claims” at the Geneva Hearings

With the appointment of his fellow Radical Republican Hamilton Fish as the new secretary of state, Sumner dropped his demands, and a joint Anglo-American commission was created to mediate the claims. In 1871, the two countries signed the Treaty of Washington, submitting their opposing claims to binding arbitration. A five-member board was empanelled to hear the charges, with representatives from the Untied States, Great Britain, Italy, Switzerland, and Brazil named to the panel.

Subsequently, a nine-month-long hearing was held in Geneva over the so-called “Alabama Claims.” Due in part to effective championing of the American position by Charles Francis Adams, who had been recalled from retirement to represent American claims, and in part by the desire of both countries to put the embarrassing diplomatic wrangle behind them, a legalistic solution was finally found.

The tribunal ruled that Great Britain had been guilty of failing to show sufficient due diligence in enforcing existing neutrality laws. The United States was awarded $15.5 million in gold for damages suffered at the hands of Confederate privateers. In turn, the British government was granted $1.9 million in damages for wartime losses to her seagoing subjects. Both nations emerged from the trial with their dignity intact, and the ghost of Alabama was finally put to rest, eight years after her watery death.

Author Roy Morris, Jr. makes a faux pas when he writes “ Sumner demanded exorbitant reparations from the British, …” and again when he writes, “ Sumner dropped his demands, …” having never introduced “Sumner” previously, apparently expecting the reader to know who “Sumner” is despite the likely thousands of persons known by that name. (It is supposed to be Senator Charles Sumner, an early advocate of civil rights.)