By Roy Morris, Jr.

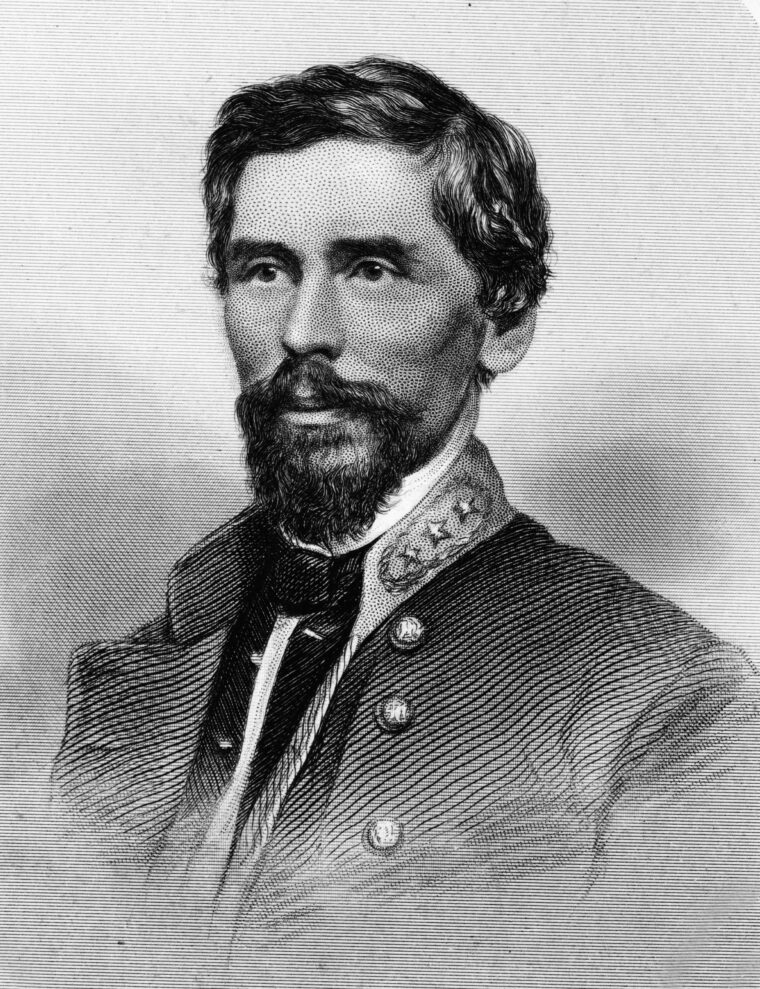

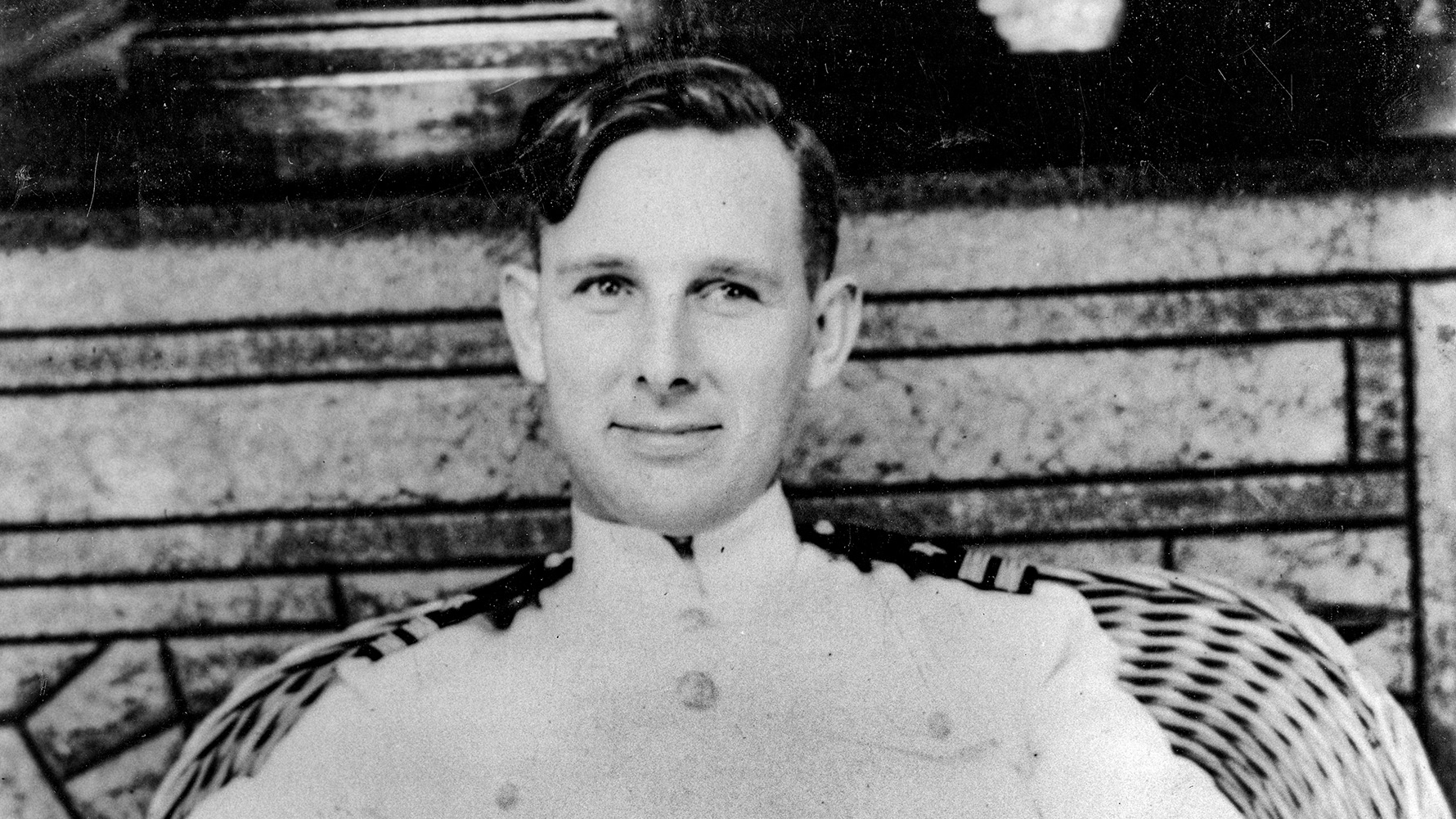

Peering through the thick underbrush west of Little Pumpkin Vine Creek, 30 miles northwest of Atlanta, on the afternoon of May 27, 1864, Ambrose Bierce had a bad feeling. That in itself was not unusual. The cynical and sardonic young lieutenant on Brig. Gen. William Hazen’s staff in the Union Army of the Cumberland was not exactly sunny natured in the best of times. Born into a dirt-poor farming family in northern Indiana and raised by fanatically religious parents, Bierce had joined the army at the very beginning of the Civil War—as much to escape his hardscrabble past as to fight for his country’s future.

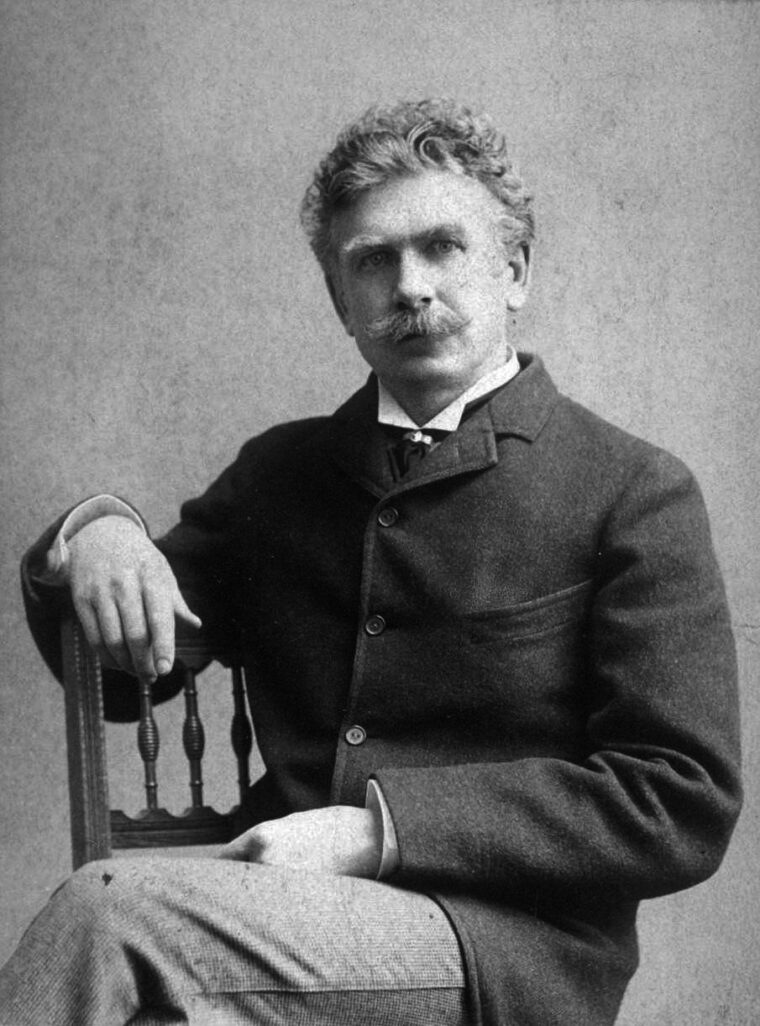

Three years on the firing line had thrown Bierce into some of the worst combat of the war, from Shiloh, Perryville, and Stones River to Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, and Resaca. Still one month short of his 22nd birthday, Bierce was a veteran in all senses of the word. As he would recall many years later, after he had become a prominent newspaper columnist and short story writer, he had spent the war years “among hardened and impenitent man-killers, to whom death in its awfulest forms is a fact familiar to their every-day observation; who sleep on hills trembling with the thunder of great guns, dine in the midst of streaming missiles, and play cards among the dead faces of their dearest friends.” If not indifferent to death, Bierce and his comrades were largely inured to it.

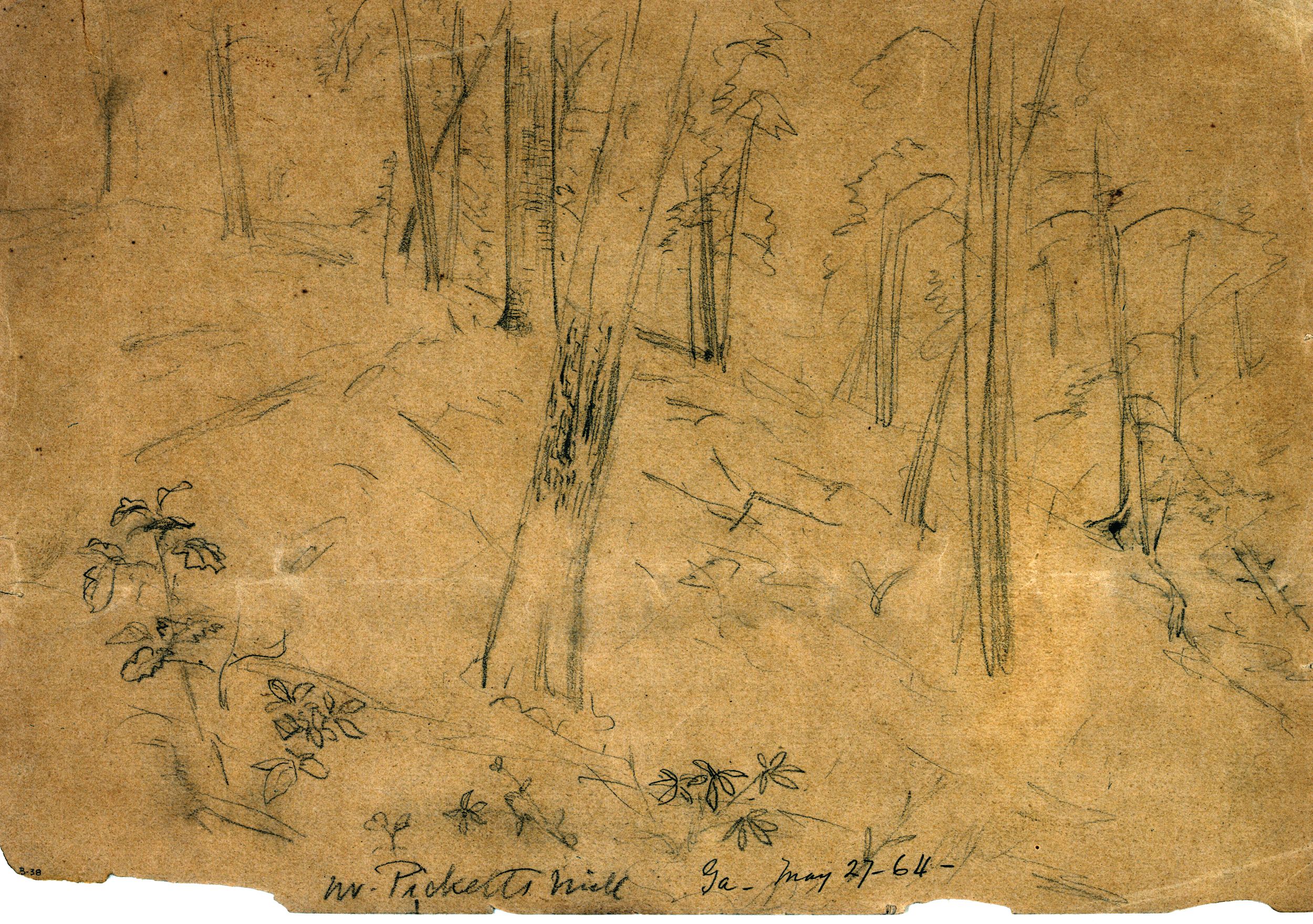

Nevertheless, something about the army’s present position did not sit well with Bierce or his fellow Midwesterners in Hazen’s brigade. “Oh, we’ll catch it today,” many of the soldiers muttered. Bierce saw nothing to cause him to disagree. In his role as a topographical engineer, it was Bierce’s job to scout and map the terrain in advance of the brigade’s movements. “My duties as topographical engineer kept me working like a beaver,” he would recall after the war. “It was hazardous work; the nearer to the enemy’s lines I could penetrate, the more valuable were my field notes and the resulting maps. It was a business in which the lives of men counted as nothing against the chance of defining a road or sketching a bridge.”

But Bierce had not had time to do much preliminary scouting of the brigade’s new position at Little Pumpkin Vine Creek. The men had just marched four miles east from New Hope Church that morning, leaving behind the trenches and breastworks they had hastily thrown up after being roughly handled by the Confederates in General Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee two days earlier. Like soldiers in all wars, they did not happily leave behind a solid defensive position to go creeping through dense, shadowy woods in search of an ever elusive enemy. It made them uneasy, to say the least.

Confusion in the Union Ranks

The big prize of the ongoing campaign was Atlanta, and the two sides had spent the past three weeks marching, fighting, and countermarching all the way from the Georgia-Tennessee border to the outer fringes of Atlanta proper. In that time, Sherman’s men had attempted incessantly to get around the Confederates’ flank and bring them to battle before they reached Atlanta. Except for one stand-up fight at Resaca 12 days earlier, a fight that Sherman’s favorite subordinate, Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson, had bungled at the outset by not sealing off a vital enemy escape route through the mountains, the Federals had been frustrated in their attempts. Johnston, a skilled strategist, had correctly intuited his opponent’s intentions, falling back repeatedly and refusing battle on Sherman’s terms. A large portion of the Southern public, seeing only the steady backward motion of Johnston’s army, had dubbed the general “Retreatin’ Joe.”

Two days earlier, however, Johnston had stood and fought at New Hope Church, near Dallas, Georgia, inflicting 1,500 casualties on the Union attackers on a rain-drenched battlefield that the Confederates dubbed the “Hell Hole.” Refusing to believe that Johnston—of all people—would dare to make another such stand, Sherman had directed one of his army’s three wings to swing around the enemy flank once more and intersperse itself between them and Atlanta.

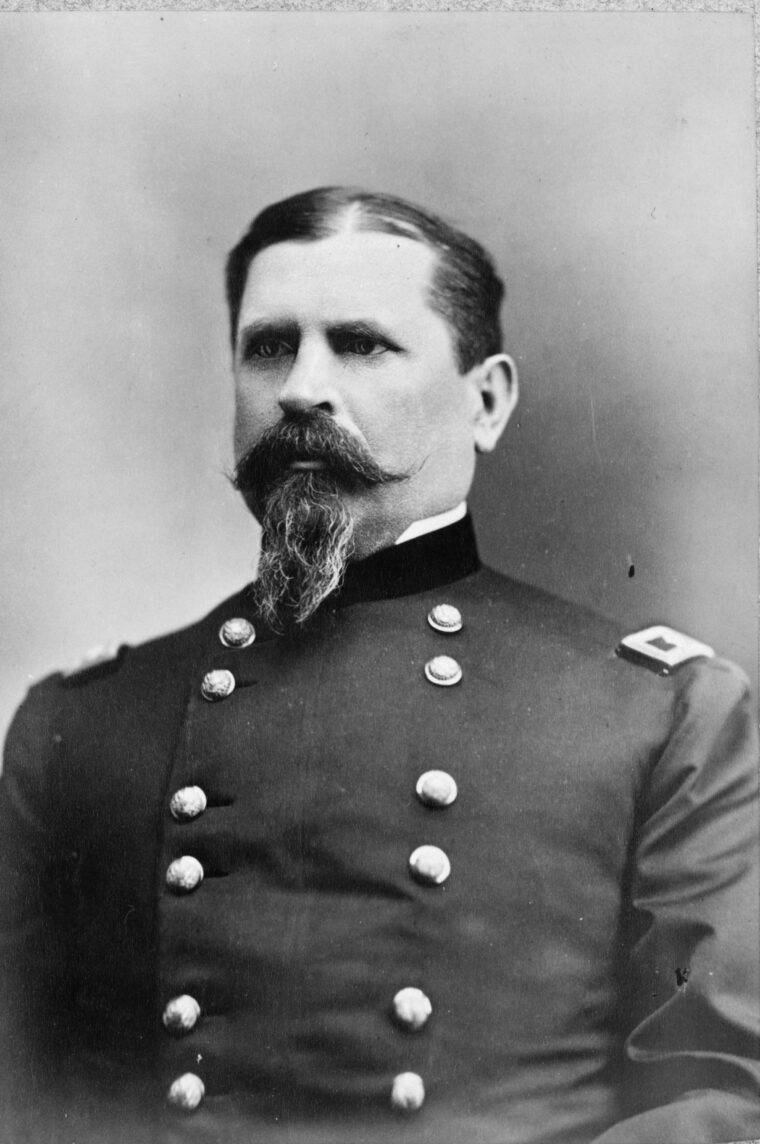

The generals Sherman chose to direct the attempt were not, to be generous, the best suited for such a task. The IV Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, and his senior divisional commander, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood, had been involved in flank attacks before—but on the receiving end. Howard, a native of Maine, had been driven from the field by Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville the previous May, and the Kentucky-born Wood had been overrun at Chickamauga four months later, while attempting to execute a misbegotten flank march at the exact moment that newly arrived Confederate General James Longstreet launched an overwhelming frontal assault. Each, understandably, was somewhat skittish to find themselves once again out on a limb.

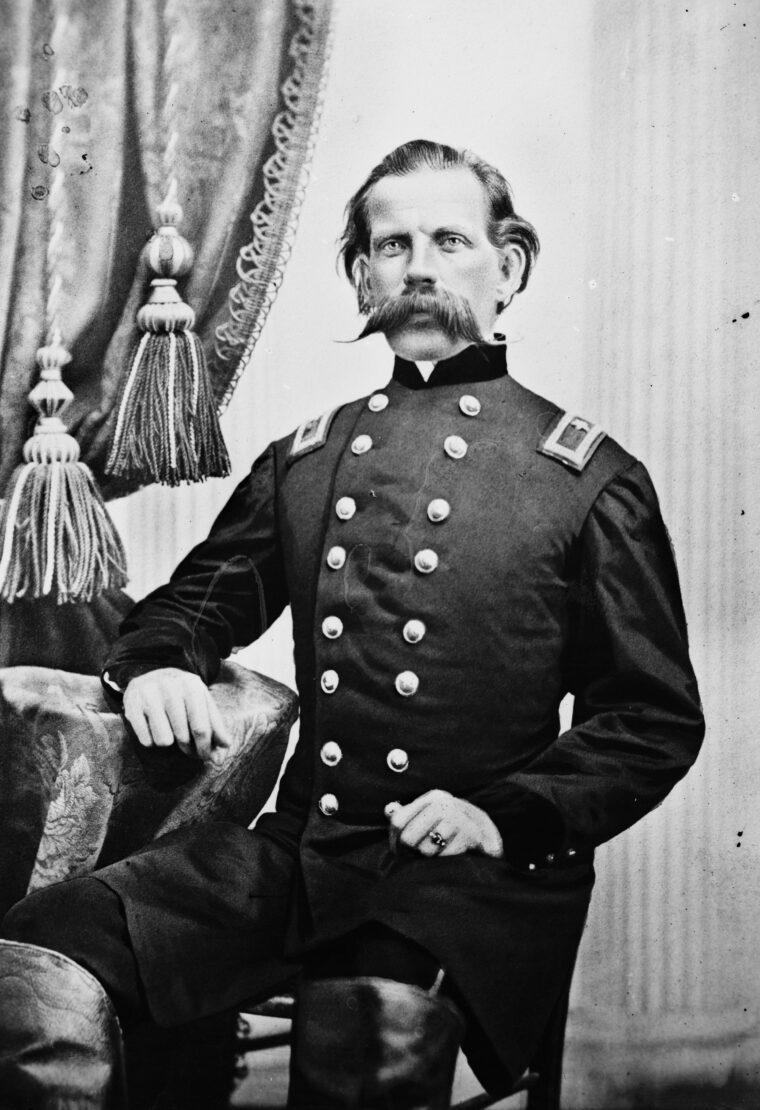

In a move that proved notably counterproductive, Union artillery commenced a vigorous bombardment of the Confederate position east of New Hope Church at daybreak on May 27. Brisk skirmishing erupted along the four-mile front. Despite his personal misgivings, Wood pulled his division out of line and began marching toward what was believed to be the Confederate right, anchored near a gristmill owned by the widow of a Southern cavalryman named Ben Pickett, who had been killed at Chickamauga. Wood had broken his division into three brigade-sized columns for the planned attack. Hazen’s brigade was leading the way, followed by those of Colonels William H. Gibson and Frederick Knefler.

The rain had ended, but the division’s progress was hampered by poor roads, soggy woods, dense scrub brush, and deep ravines. Two companies became hopelessly lost in the woods, and a third managed to keep lurching in the right direction only because battalion commander Lt. Col. Robert Kimberly of the 41st Ohio Infantry was able to utilize a pocket compass he had been given as a gift. A favorite aide of Howard’s managed to get himself shot through the chest when he stepped carelessly into an open pasture to try out his new field glass.

Unnerved by the incident, Howard characteristically dithered. Known to his men by the unflattering nickname “Uh-Oh” Howard, the general did not inspire confidence in the best of times. His empty sleeve, courtesy of a battlefield amputation at the Battle of Seven Pines, seemed like an ominous portent to the troops. (Ostentatiously religious, Howard favored another nickname, “the Christian general.”) For two hours, the men milled about in confusion while buglers continually blared away in a less-than-stealthy attempt to keep order in the ranks. Bierce termed the unfortunate delay an attempt “to alert the enemy of our intention to surprise him.”

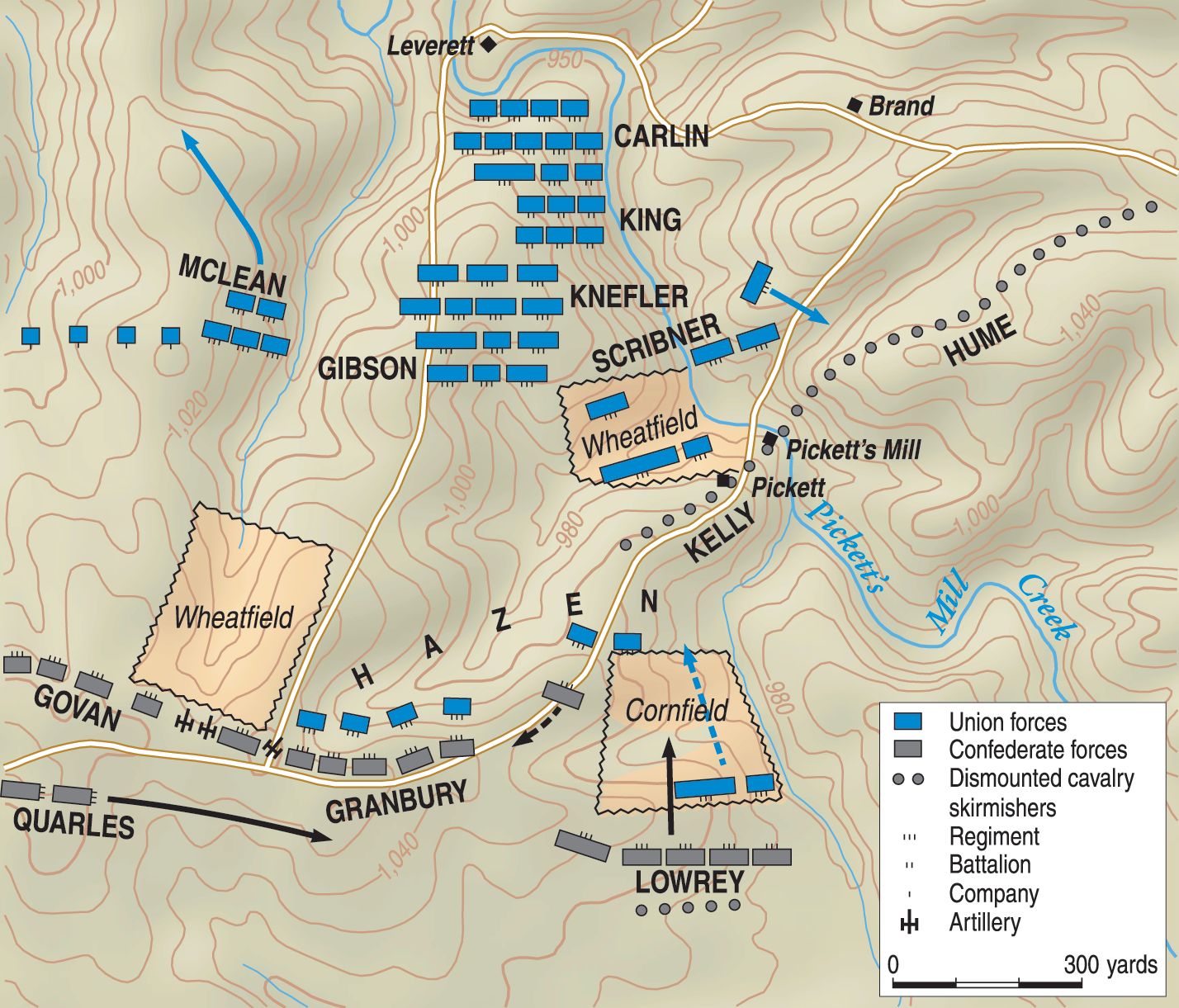

The battle-savvy Confederates needed no additional aid to alert them. Johnston had already reinforced his right flank with 5,000 of his best fighters, the much-feared division commanded by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, an Irish immigrant turned Arkansas lawyer who had earned a well-deserved reputation as one of the South’s best officers. Cleburne had extended his lines farther to the right, positioning an artillery battalion at the end to further cement his defenses. The veteran Confederates had quickly thrown together rifle pits and linked them to trees and boulders along the ridges beyond Little Pumpkin Vine Creek. They were ready and waiting for any enemy approach.

The Disastrous Attack Begins

At 4 pm, Howard received a terse order from Sherman telling him to “get on the enemy’s flank and rear as soon as possible.” Wood, understandably perplexed, asked Howard for clarification. “Are the orders still to attack?” he wondered. “Attack,” said Howard. “We will put in Hazen and see what success he has,” Wood responded airily. Hazen, who was under the impression that there was to be a simultaneous attack by all three brigades, was thunderstruck by the casual change in plans. He saluted and rode back to his brigade to prepare the men for the suicidal assault. “Only by a look which I knew how to read did he betray his sense of the criminal blunder,” Bierce recalled.

By 4:30, Hazen had his 1,500 men in position for the futile attack, formed into two lines of two battalions each. The artillery fire had stopped, and only the steady dripping of water from the rain-soaked trees broke the sudden silence. Bierce, who had pushed forward far enough to hear the murmuring of the Confederates on the other side of the creek, waited uneasily. “This, then, was the situation,” he recalled, “a weak brigade of fifteen hundred men, with masses of idle troops behind in the character or audience, waiting for the word to march a quarter-mile uphill through almost impassable tangles of underwood, along and across precipitous ravines, and attack breastworks constructed at leisure and manned with two divisions of troops as good as themselves.”

Hazen’s brigade advanced along a 200-yard front, its progress immediately stymied by a deep ravine that cut across its path. The underbrush was so thick around them that the color-bearers had to keep their flags furled to prevent them from being torn to pieces by low-lying branches. Gray-clad skirmishers immediately fell back at the Union approach, which caused some of the Federals to shout erroneously, “Ah, damn you, we have caught you without your logs now!” Southern voices immediately retorted, in sarcastic reference to published newspaper reports that they were suffering from low morale, “Come on, we are demoralized!”

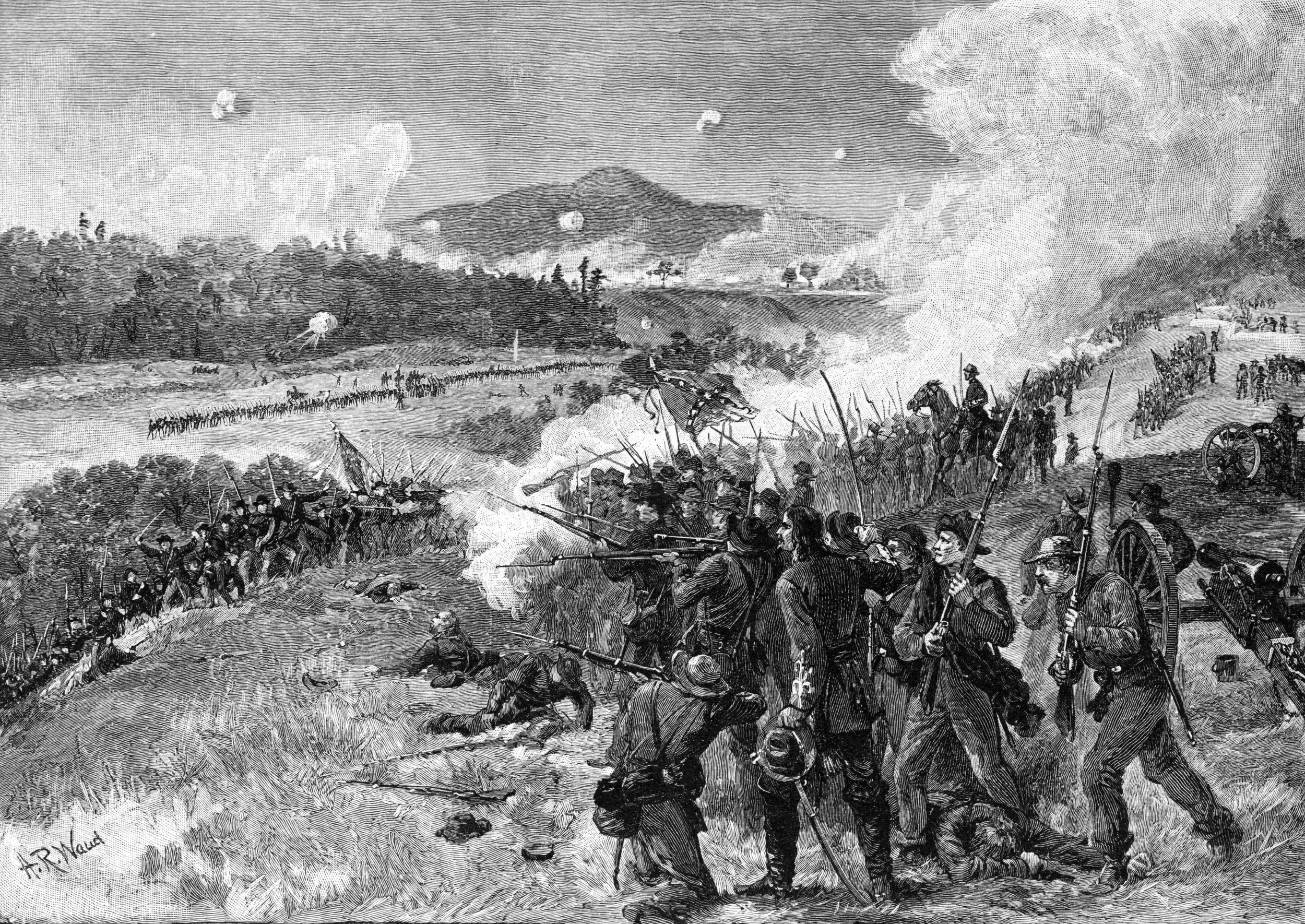

Hazen’s brigade labored through the ravine and up the rock-strewn hillside, the color bearers now breaking out their flags and waving them back and forth in the still dusk air. Then, seemingly as one, the Confederates opened fire. Bierce, who was advancing on foot on the far right of the formation, as were all the brigade officers, heard “a ringing rattle of musketry, the familiar hissing of bullets, and before us the interspaces of the forest were all blue with smoke. Hoarse, fierce yells broke out of a thousand throats. The uproar was deafening, the air was sibilant with streams and sheets of missiles.” Gusts of grapeshot mingled with the uninterrupted fire of the Southerners’ muskets, crackling through the branches and tree trunks that afforded the attackers little cover and no safety.

It was the brigade’s singular misfortune to be attacking Cleburne’s division, which had stopped Sherman in his tracks at Missionary Ridge the previous November and treated him roughly again at Resaca two weeks earlier. Not that it made much difference whom they were attacking; by this time in the war, any veteran troops holding fortified high ground could have beaten back the unsupported assault of a single brigade attacking over virtually impassable terrain. Cleburne later gave the Union troops at Pickett’s Mill a backhanded compliment, saying that they had “displayed a courage worthy of an honorable cause.” Nevertheless, he noted, “As they appeared upon the slope [we] slaughtered them with deliberate aim.”

Howard sent back a troublingly uncertain message to Sherman: “I am now turning the enemy’s right flank, I think.” Not really. Cleburne, calm as always, brought up Brig. Gen. Hiram Granbury’s Texas brigade from its reserve position and had it fall in on the right to further extend the Confederate line. The Texans responded at the double-quick, clambering up a ridge with a 50-yard incline that gave them a clear field of fire. Lying flat on the ground, they waited like the seasoned hunters they were until the Union quarry was within their gun sights, then unleashed a new torrent of fire.

To Colonel Kimberly, whose Ohio troops anchored the center of Hazen’s line, the Rebel volley was as sudden and unexpected as “a lightning stroke from a cloudless sky.” Men fell by the dozens, almost soundlessly in the maelstrom around them. Somehow, Hazen’s veterans pressed on, their line broken up and irregular as more and more men fell to the ground. Almost by accident—a function of the peculiar topography of the battlefield—the Confederates had prepared a perfect slaughter pen. By extending the right flank, Granbury’s Texans had linked up at a right angle to Brig. Gen. Daniel Govan’s brigade, creating a deadly crossfire effect. Quick-thinking artillerists had rolled forward a Parrott gun and two howitzers at the junction of Govan’s and Granbury’s lines, further intensifying the already murderous fire.

Bierce and the other officers in Hazen’s brigade could only watch aghast as their crack troops were cut down. “Our brave color-bearers were now all in the forefront of battle in the open,” noted Bierce, “for the enemy had cleared a space in front of his breastworks. They held the colors erect, shook out their glories, waved them forward and back to keep them spread, for there was no wind. From where I stood, at the right of the line, I could see six of our flags at one time. Occasionally one would go down, only to be instantly lifted by other hands.”

“The Dead-Line”

Due to an almost incredible confluence of mistakes and timidity, both of Hazen’s flanks were left completely unguarded. On the right, Howard had ordered Colonel Nathaniel McLean to post his brigade at the edge of a wheat field opposite Govan’s troops and occupy the Confederates in his front. Unbelievably, while the fighting was at its height McLean abruptly marched his unengaged brigade to the rear, explaining lamely that his men needed to draw their rations. He, at least, had no stomach for the fight.

Meanwhile, on Hazen’s left Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson—ordinarily a tough, dependable fighter—was unaccountably slow in getting his lead brigade into line to support the attack. While Johnson dithered, the Union attackers somehow managed to gain control of a ridge on the Confederate right-rear, temporarily threatening the entire enemy line. Confederate cavalry commander John Kelly, at 23 the youngest brigadier general in the Confederate Army, slowed the Union advance long enough for Colonel George Baucum’s consolidated 8th and 19th Arkansas Regiment to rush up and plug the gap.

Hazen’s men were caught in a tornado of small arms and artillery fire. Some individuals managed to come as close as 10 paces to the Confederate line before they were shot down. None made it any closer. Confederate Captain Samuel Foster later counted 50 Federal dead in a 30-foot circle. Most of them had been shot in the head with “their skulls busted open and their brains running out.” It was a literal dead-line—the point at which no one could stand erect and live to tell about it—and Hazen’s survivors threw themselves down and buried their faces into the ground.

“Not a soul of them ever reached the enemy’s front to be bayoneted or captured,” recalled. Bierce. “It was a matter of the difference of three or four paces—too small a distance to affect the accuracy of aim. In these affairs no aim is taken at individual antagonists; the soldier delivers his fire at the thickest mass in his front. The fire is, of course, as deadly at twenty paces as at fifteen; at fifteen as at ten. Nevertheless, there is the dead-line, with its well-defined edge of corpses—those of the bravest. Where both lines are fighting without cover—as in a charge met by a counter-charge—each has its dead-line, and between the two is a clear space, neutral ground, devoid of dead, for the living cannot reach it to fall there.”

Gibson’s Assault

Forty-five minutes after the Union attack began, it came to a brief, exhausted pause. Hazen’s brigade was virtually destroyed; nearly a third of the 1,500 men who began the attack were dead or wounded, many within the first few minutes of the assault, and those who could do so were staggering back to the rear to take cover in a ravine. Hazen sent back word to Howard to order Gibson into the fray, but for Hazen and his men it was too late to do any good. Gibson’s troops went forward up the deadly slope with admirable bravery but met the same fate as Hazen’s men. “The enemy had destroyed us,” reported Bierce, “and was now ready to perform the same kindly office for our successors.” When a young soldier who had been separated from his unit asked Hazen where he located his brigade, the hard-bitten general, choking back tears, replied: “Brigade, hell, I have none. But what is left is over there in the woods.”

If anything, the Confederates were even better prepared to meet Gibson’s attack. During the brief lull in firing, they had replenished their ammunition and stacked more fence rails, logs, and fallen branches on top of their breastworks. With no support from Johnson’s still uncommitted division, Gibson’s brigade met the same fate that Hazen’s had just endured. In less than an hour, Gibson suffered nearly 700 casualties. Like Hazen’s troops, there was a disproportionate number of dead to wounded—the Confederates had simply shot many of the Union soldiers in the head within 10 to 20 paces. At that range, few experienced marksmen could miss.

Confederate commander Joseph Johnston described the fighting in his official after-action report: “The Fourth Corps came on in deep order and assailed the Texans with great vigor, receiving their close and accurate fire with the fortitude always exhibited by General Sherman’s troops in the actions of this campaign. The Federal troops approached within a few yards of the Confederates, but at last were forced to give way by their storm of well-directed bullets, and fell back to the shelter of a hollow near and behind them. They left hundreds of corpses within twenty paces of the Confederate line.”

Granbury’s Night Attack

At 6 pm, just after the second futile Union attack had begun, Howard received orders from Sherman to call off the attack and link up with the XXIII Corps to protect his flank while Sherman began a march toward the railroad depot at Acworth. All Howard had needed to do was to make sure that Johnston did not get around his flank and cut off Sherman’s route to the rail line. The slaughter of Hazen’s and Gibson’s men had been an irrelevant afterthought.

While Howard was preparing in his overly deliberate way to put his unexpected new orders into effect, a shell fragment ripped off part of his boot. Having already lost an arm in Virginia, Howard was understandably terrified of losing another limb. “I am afraid to look down! I am afraid to look down!” he gasped. Miraculously, the shell had only ripped off the bottom of his boot and left his bare foot badly bruised but still intact. Howard limped to the rear, where he spent the rest of the evening directing the battle “among the maimed” in the forest, his throbbing foot taking up much of his psychic attention.

Howard sent one last wave of attackers forward, not to break the Confederate line but to recover the Union wounded. The Rebels were not prepared to be merciful. They unleashed another devastating volley into the advancing bluecoats, who quickly cut short their recovery efforts and took what shelter they could behind trees and rocks. They would wait for nightfall before sending out patrols to gather up the wounded, whose cries and moans filled the no-man’s-land between the two lines.

One final indignity awaited the Union forces at Pickett’s Mill. At 10 pm, Granbury’s men quietly formed ranks to launch a night attack. Captain Foster recalled that the Federal line was so close that “we could hear the Yanks just in front of us moving among the dead leaves on the ground like hogs rooting for acorns, but none speaking above a whisper.” At the blare of a bugle, the Confederates unleashed a terrific yell and fell upon the startled enemy at one bound. The Federals managed to fire one volley before scampering en masse to the rear.

Granbury’s men fanned out and scoured the woods for stragglers. In the confusion and darkness, they demanded that all the soldiers they came upon identify themselves immediately by regiment. According to one somewhat illiterate Texan: “Sometimes the answer would be the 40th, and our boy’s knew that we dit not have no 40th Regt. In our Brigade, and, therefore, they would Kill such. Sometimes the answer would be the 24th, and when they would ask the 24th What, ‘the 24th Ohio,’ and they were servet the same.” As many as 20 Union troops would be discovered huddling behind the same log and, according to another Rebel diarist, “All they would say was ‘Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!’”

The Aftermath of the Crime at Pickett’s Mill

By midnight, the sporadic firing had died away. The Battle of Pickett’s Mill was over. The pious Howard, nursing his sore foot, looked on with distaste as some of his men proceeded to get well and understandably drunk. “Faint fires here and there revealed men wounded, armless, legless, or eyeless; some with heads bound up with cotton strips, some standing and walking nervously around, some sitting with bended forms, and some prone upon the earth,” wrote Howard. “A few men, in despair, had resorted to drink for relief. The sad sounds of those in pain were mingled with the oaths of the drunken and the more heartless. That night will always be a sort of nightmare to me.”

At least Howard would live to remember it. Dawn revealed how costly the battle had been. Of the 1,600 total Union casualties, 700 had been killed outright. A Mississippi lieutenant attributed the “wonderful” disparity of dead to wounded to the “over-ruling Providence of God.” A Texas comrade, less spiritually transported, looked at the pitiful scattering of letters and ambrotypes among the Union dead and thought of the mothers, sisters, and friends who had sent them to the soldiers in the first place. “Though they had been my enemies, my heart bled at the sickening scene,” the Southerner reported.

In the aftermath of the miscarried battle, an embarrassed cloak of silence, if not outright secrecy, immediately surrounded the Union high command at Pickett’s Mill. The ordinarily loquacious Sherman casually informed General-in-Chief Henry Halleck in Washington, “We have had many sharp, severe encounters, but nothing decisive.” Beyond that vague mention, Sherman never wrote a single word about Pickett’s Mill in his official reports or his best-selling memoirs. Howard, too, fell silent—an unaccustomed state of affairs for the usually bombastic general.

It remained for 1st Lt. Ambrose Bierce alone to remember his fallen comrades at Pickett’s Mill. Settling in San Francisco after the war, Bierce became a well-known and much-feared newspaper columnist, the “wickedest man in San Francisco,” as one nickname put it. On May 27, 1888—the 24th anniversary of the Battle of Pickett’s Mill—Bierce published an account of the butchery in his newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner. He titled it: “The Crime at Pickett’s Mill: A Plain Account of a Bad Half Hour with Joe Johnston.” It had been that, and more. Indeed, for some 700 Union soldiers in the north Georgia woods, it had been the last day of their lives. Nor did Bierce, with his hard-won cynicism, have much faith in history eventually doing justice to the dead at Pickett’s Mill. As he defined it in his tart work of lexicography The Devil’s Dictionary, history was merely “an account mostly false, of events mostly unimportant, which are brought about by rulers mostly knaves, and soldiers mostly fools.”

There were knaves aplenty at Pickett’s Mill, most of them in positions of leadership in the Union ranks. And as usual, it was the “fools”—the common soldiers under their command—who paid in blood for the mistakes made by their misbegotten commanders. Years later, Bierce was still challenging Howard to write “one line” about the fallen of Pickett’s Mill, but “the consummate master of the art of needless defeat” continued “to ignore their hopeless heroism.” It did not surprise Bierce, and it probably would not have surprised his dead comrades at Pickett’s Mill, but they were now beyond all caring.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments