By Roy Morris Jr.

It is somehow fitting that the Boer War spanned the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, since the conflict itself represented both the last old-fashioned war and the first modern one. It was simultaneously a war for empire and a guerrilla insurgency, with titled British gentlemen leading khaki-clad troops against Boer sharpshooters wearing civilian clothes. The badly outnumbered Boers had no intention of fighting a conventional war against the massive might of the British Army. Instead, they melted into the bush, sniping at enemy columns and blowing up trains. The British, raised on time-honored notions of fair play and drawing-room etiquette, quickly took umbrage at their South African opponents’ less sporting approach to mortal combat. A war that began with 19th century manners soon descended into 20th century brutality.

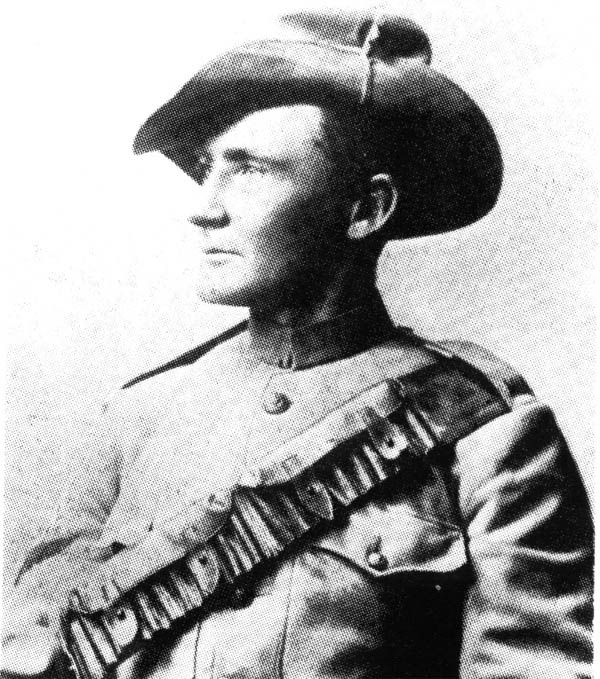

No single event is more revealing of the schizophrenic nature of the Boer War than the trial and execution of Lieutenant Harry “Breaker” Morant and his fellow officer, Lieutenant Peter Handcock, in the winter of 1902. The two men, members of the counterinsurgency unit, the Bushveldt Carbineers, were accused of shooting unarmed Boer prisoners and a German missionary the previous summer, in retaliation for the ambush and murder of their friend and superior, Captain Percy Hunt. The details of their trial before a closed British court-martial created a storm of controversy in their homeland of Australia, but by the time the story had leaked out, Morant and Handcock had already been shot by a hastily organized firing squad in the Transvaal capital of Pretoria.

Did Kitchener Give the Orders?

The exact events leading up to the executions remain hazy to this day. It is indisputable that a number of Boer prisoners were shot, either on Morant’s orders or those of Captain Alfred Taylor, an English intelligence officer temporarily assigned to the Bushveldt Carbineers. But a central tenet of Morant’s defense was that he was merely following long-standing orders—orders he said had come down from British Army commander Lord Kitchener himself. According to Morant and his attorney, Major J.F. Thomas, such orders were known and understood by all units in the field. High-ranking authorities denied that such orders had ever been given—Kitchener was conveniently away from headquarters at the time, touring far-flung troop deployments—but a recently discovered diary kept by his provost marshal, Robert Poore, revealed that “Lord K. has issued an order to say that all men caught in our uniform are to be tried on the spot and the sentence confirmed by the commanding officer.”

Given the fact that Kitchener was also the author of the army’s notorious practice of confining Boer women and children to concentration camps, it is not too much of a stretch to believe that he did, indeed, order the summary execution of Boer prisoners. The fatal mistake made by Morant and Handcock, as Poore says in his diary, is that “if they had wanted to shoot Boers they should not have taken them prisoner first.”

Morant, a swashbuckling figure in his adopted homeland, was renowned for his horse-breaking ability—hence his nickname. His famous last words to the firing squad, “Shoot straight, you bastards! Don’t make a mess of it!” rapidly entered Australian folklore, as did his mordant analysis of the court-martial that convicted him: “We’re scapegoats of the Empire.”

In 1979 the Australian-made film Breaker Morant brought renewed interest to the controversial case. Like most movies based on complex historical events, it drastically oversimplified matters, and the film’s star, Edward Woodward, admitted later that his title character was probably “a good deal rougher and tougher” than Woodward played him. Nevertheless, Breaker Morant is a stirring piece of film-making and an eloquent indictment of a new kind of war, one whose morally ambivalent nature has become all too familiar to both soldiers and civilians in the century since it first saw the light of day. Sometimes justice, like war, is merely politics by other means.

Studied this battle at the Infantry School in 1973

The movie was fantastic. It was low budget but it was so successful it saved the Austrailian film industry almost single handedly. Besides Handcock and Morant there was a third person on trial who was spared from execution – George Witton. In his 1907 book “Scapegoats of the Empire,” Witton’s main assertion, as indicated by the book’s attention getting title, was that he, Morant, and Handcock were made scapegoats by the British authorities in South Africa-that they were made to take the blame for widespread British war crimes against the Boers. He asserted that the trial and executions were carried out by the British for political reasons, partly to cover up a controversial and secret “no prisoners” policy issued by Kitchener, and partly to appease the Boer government over the killing of Boer prisoners. This was done to help secure a peace treaty to end the war. As it happened the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on 31 May 1902.