By Chuck Lyons

Not all those who died in World War II died in combat. There were also illness, heart attacks, cancer, friendly fire … and accidents.

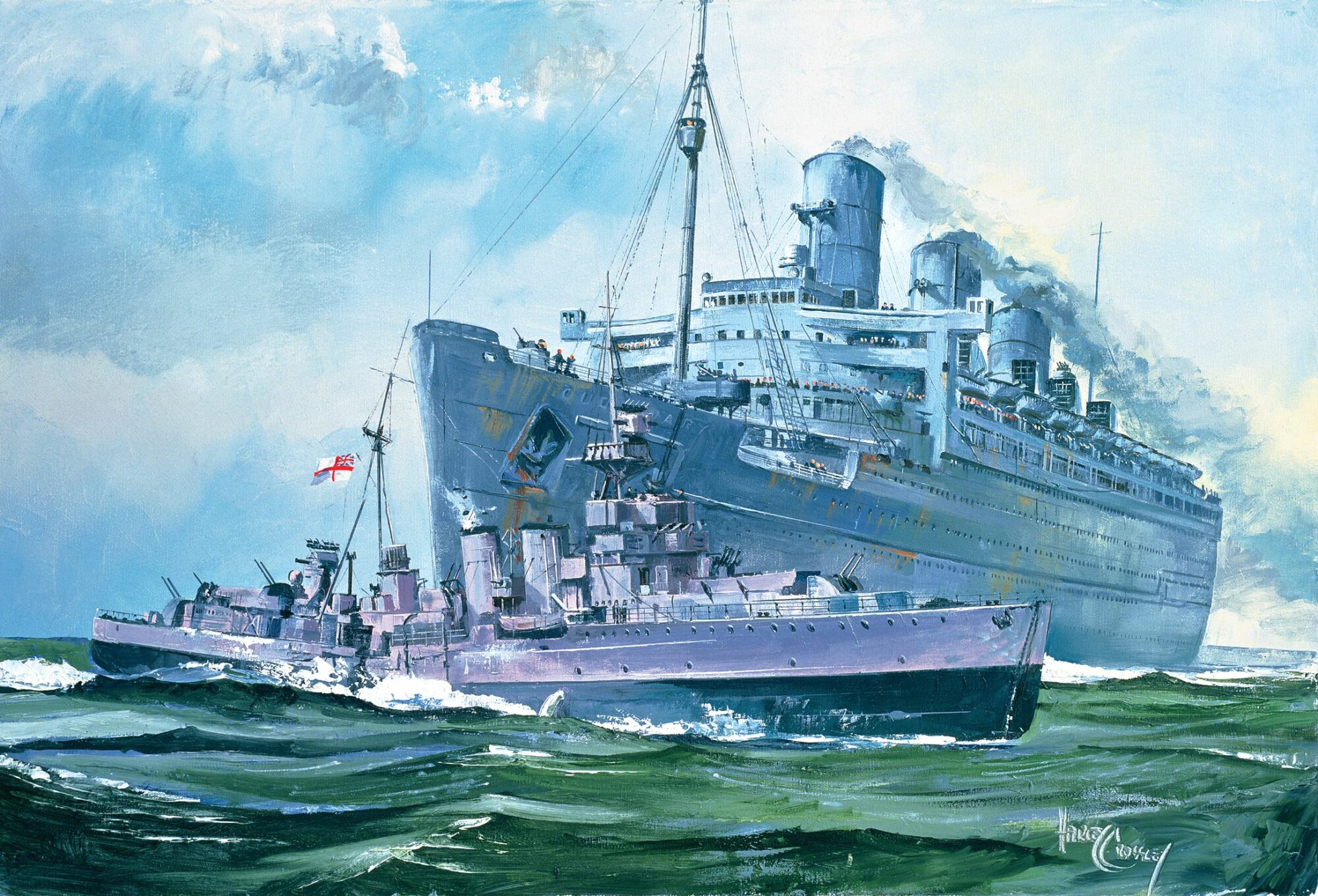

One of the worst accidents occurred on October 2, 1942, when a British antiaircraft cruiser and the famous British liner Queen Mary collided. The mishap cost 236 British seamen their lives; only 99 were rescued.

During World War II many of the great Atlantic liners, such as the luxurious, 1,020-foot-long Queen Mary (which had a comfortable capacity of 1,174 passengers) and her sister ship Queen Elizabeth were converted into troop carriers, each capable of carrying more than 15,000 troops. The two ships were the largest and fastest troopships involved in the war and, because of their speed, often traveled out of convoy and without escort. By the end of the war, the two ships transported more than 800,000 troops.

Queen Mary had been launched in September 1934 and had served the Atlantic trade from 1936, when she set a speed record for the Atlantic crossing, until the outbreak of the war, when she was converted to troop-carrier duty.

At that time, six miles of carpet, 220 cases of china, crystal, and silver service, tapestries and paintings were removed and stored in warehouses for the duration of the war.

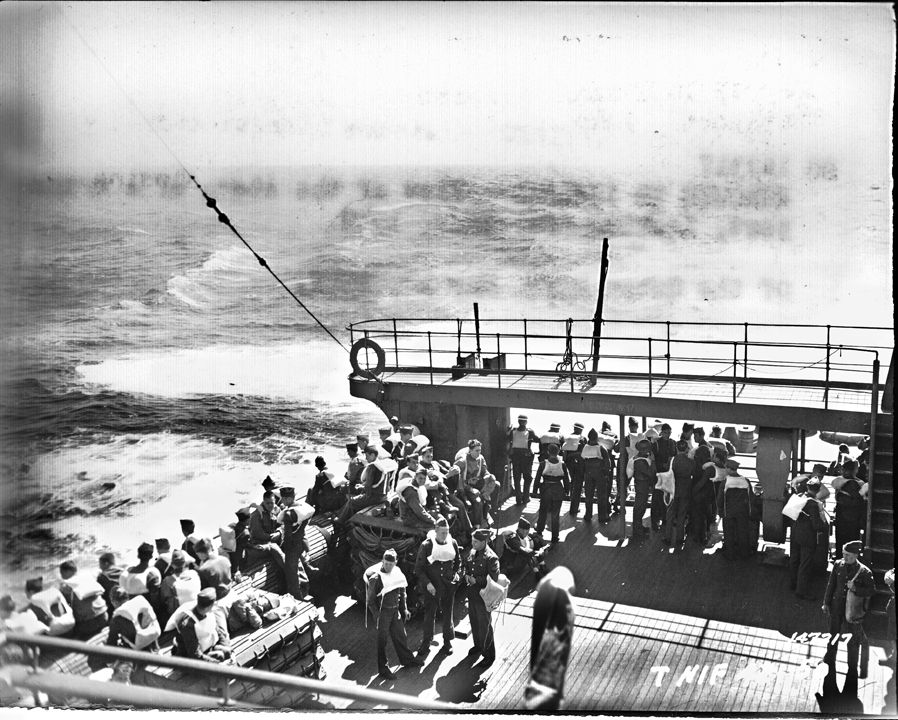

She was fitted with tiered bunks for the men she would be transporting. Troops slept in shifts. The Queen’s swimming pool was drained, and she was painted gray, which, combined with her speed, gave birth to her wartime nickname of “Gray Ghost.”

Likewise, the war led to a number of military ships also being converted to other uses. Originally launched as a light cruiser May 5, 1917, the Curaçao had seen brief service in the latter days of World War I. In 1939, a few months before the outbreak of World War II in Europe, she was selected for conversion to an antiaircraft cruiser and underwent a refit at Chatham Dockyard in Kent. She served during the Norwegian Campaign in 1940 but on April 24 of that year sustained heavy damage and 30 casualties from aerial bombing, forcing her to withdraw to Chatham for repairs. Manned with a crew of 338, she was returned to active duty in August, serving mainly as an escort for convoys.

As the war progressed, Queen Mary’s role as a troop transport became so significant to the Allied war effort that Adolf Hitler offered a $250,000 reward and military honors to any captain in the German navy who could sink the vessel.

On October 2, 1942, Queen Mary was rounding the north coast of Ireland on the last leg of her journey from New York to a Scottish port with the 29th Infantry Division aboard (the 29th was joining the buildup of Allied forces in Britain and would later take part in the Normandy invasion at Omaha Beach). Since she was now within range of German aircraft, she was joined by escorting vessels, including Curaçao. Both ships were sailing evasive zigzag courses about 37 miles north of the coast when the liner cut across the path of the cruiser, striking her amidships at a speed of 28 knots.

The collision tossed sailors on the upper deck of the cruiser “like falling autumn leaves,” as one witness reported it, into the freezing waters of the Atlantic.

“The Queen Mary sliced the cruiser in two like a piece of butter,” Alfred Johnson, a 22-year-old crewman on the Queen, later said.

The Curaçao’s stern sank quickly, taking many crew members trapped behind closed watertight doors to their deaths and leaving the few seamen who had survived clinging to bits of wreckage in the icy North Atlantic water for, some say, as much as four hours before being rescued.

The fore section of the ship soon followed. Crew and passengers on the converted liner watched in horror as Curaçao went under only 100 yards away.

Because of the threat of German U-boats, Queen Mary did not stop for rescue operations but instead steamed onward with a fractured stem, the forwardmost part of a ship’s bow, being escorted by the Polish destroyer ORP Blyskawica, which had taken over from Curaçao.

“The Queen Mary just carried on going,” Seaman Johnson said. “It was the policy not to stop and pick up survivors even if they were waving at you. It was too dangerous.”

Hours later two escort ships returned and rescued only 99 survivors from Curaçao’s original crew of 338, including her captain, John W. Boutwood. Harry Grattidge, an officer on the Queen, has written, however, that the Queen’s captain ordered the accompanying destroyers to look for survivors within moments of Curaçao’s sinking.

“What a terrible sight it was,” said Able Seaman Enoch Foster, who was aboard the destroyer HMS Bramham assisting in the rescue. “The sea was covered in oil, dirty and black, with hundreds of heads with oily faces and panicky white eyes, mouths opening and closing like fish, some shouting for their mothers and help, others just choking with fuel oil in their lungs and dying.”

Most of those killed, however, remained entombed in the shattered halves of Curaçao. Only 21 bodies washed ashore and were buried.

A recent book has suggested that a German submarine, U-407, had sighted the Queen shortly before the accident and further suggests the Queen was, in fact, zigzagging in an attempt to prevent U-407’s approach, but that claim remains unproven.

The October accident has been blamed on a number of factors besides the possible U-407 sighting, including assumptions on the part of both captains that did not prove to be correct. For one, the captain of Queen Mary, Giles G. Illingworth, was believed to be operating on the assumption that her escorting cruiser would observe her course change and adjust accordingly.

At the same time, Captain Boutwood aboard Curaçao assumed the standard seafaring rule that an overtaking ship must yield the right of way would be observed. The resulting convergent courses of the two ships were also said to have been reported aboard both ships, and Queen Mary’s first officer is said to have issued a correction, but the reports and correction were apparently dismissed by the both ships’ captains.

In addition, due to the speed of Queen Mary, communication between her and Curaçao was often delayed; at one point it took an hour to deliver a message from Curaçao to the Queen. It was further determined that Queen Mary’s compass was at the time off by two degrees, a fact unknown to her captain and crew but which could have contributed to what happened.

The sinking and loss of life were not reported until after the war for fear of the effect such an announcement would have on troop and civilian morale. After the war ended, however, and the Curaçao sinking had been made public, the Royal Navy pressed charges against Queen Mary’s owners, Cunard White Star Line (the owners of the doomed Titanic).

Originally, Curaçao was ruled to be responsible for the accident but, on appeal, the British High Court of Justice ruled that two-thirds of the blame for the accident lay with Curaçao and one-third with Cunard White Star Line, a ruling that proved significant in the flurry of lawsuits that followed.

Queen Mary, which was refitted and returned to commercial transatlantic service after the war, retired in 1967. The ship is permanently docked in Long Beach, California, where she serves as a museum, hotel, restaurant, and major tourist attraction.

She is also believed to be haunted.

Among the numerous reports of paranormal phenomena aboard her are reports of men screaming and of metal crushing against metal.

Most of these reports place the source of these sounds below decks at the extreme front end of the ship—the site of the collision between the Queen and HMS Curaçao that fateful day in 1942.

Hitler’s $250,000 reward for sinking Queen Mary was never collected, but an accident at sea almost accomplished what the German Navy could not.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments