By Mike Phifer

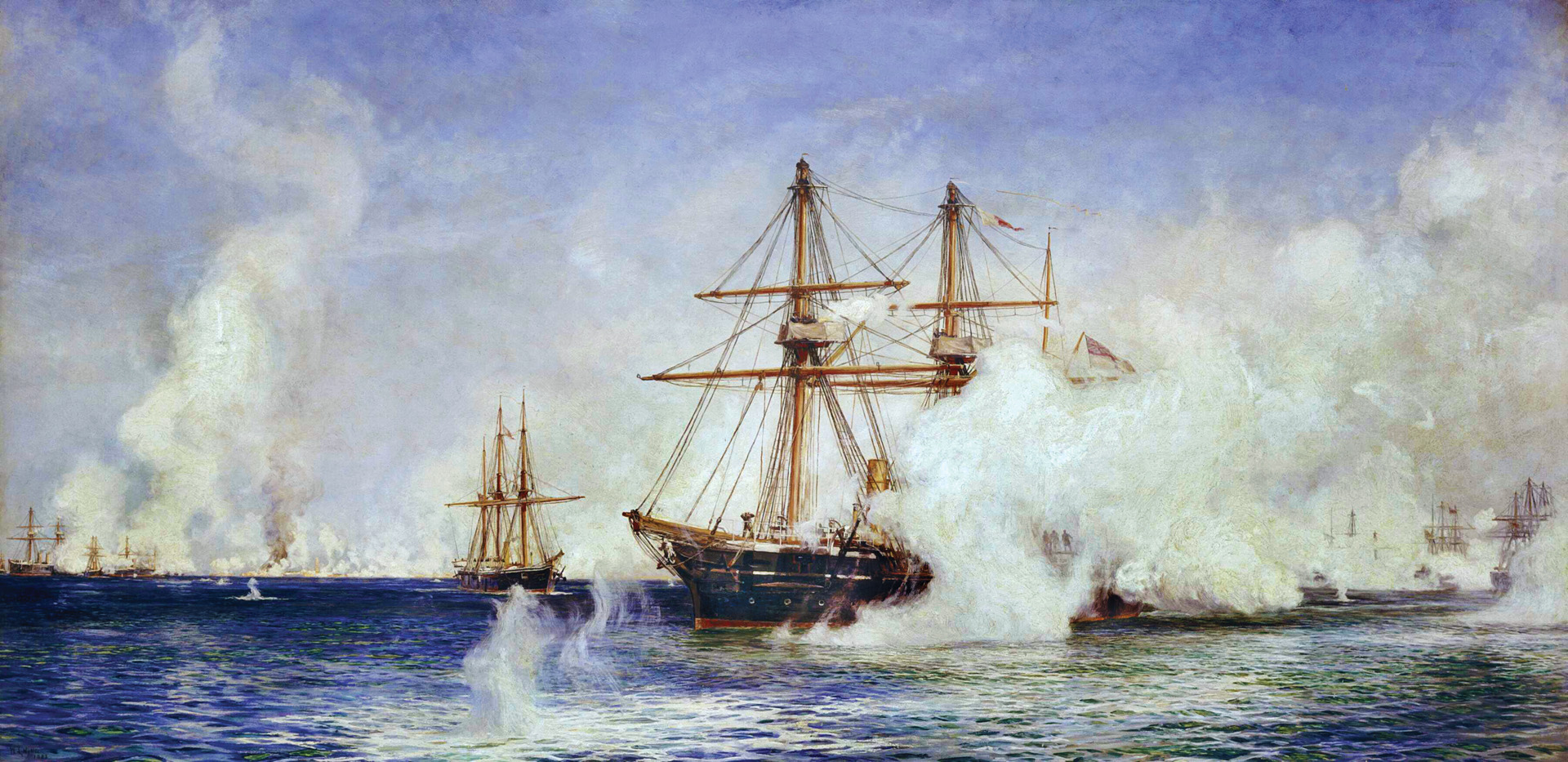

The crew of the HMS Alexandria waited anxiously for battle in the minutes before 7:00 am on July 11, 1882. The ship’s sailors, who were stripped down to their flannel jerseys, waited for the order to fire the ironclad’s heavy guns. The sailors on the seven other ironclads and five gunboats of the flotilla also stood ready at their respective vessels’ guns for the signal shot to begin bombarding the forts and earthworks protecting the harbor of the Egyptian city of Alexandria. The British had sent an ultimatum to the Egyptians instructing them to remove their menacing guns covering their fleet anchored nearby. The Egyptians had flatly refused.

At 7:00 am a lone gun bellowed from the Alexandria—the signal for the attack to begin. The guns of the Royal Navy vessels now began to fire. Smoke filled the air as the guns continued to thunder away. Sweating sailors quickly reloaded the ships’ muzzle-loading guns. Multi-barreled guns, the Nordenfelts and Gatlings, added their firepower, rattling away from the vessels’ decks and masts.

Egyptian gunners quickly returned fire. Captain Arthur Wilson, commanding the torpedo depot vessel HMS Hecla, watched the bombardment. He noted that the Egyptians “showed a great deal of pluck” manning their guns until they were disabled. Meanwhile, the British sailors continued to hammer away, the gunners cheering or jeering depending on whether targets were hit or missed. At that point in the hostilities “it was all good fun and the men rather looked upon it as a fine lark,” recalled Lieutenant George Field aboard the HMS Sultan. When the gunners began taking casualties from counter-fire, their attitudes changed. “Now it was thorough earnest determination throughout,” said Field.

Both sides continued to hammer away at each other, but the Egyptians were getting the worse of it. In the early afternoon, one of the forts exploded as its magazine was hit, sending a bright burst of flame skyward followed by black smoke and flying debris. The British sailors continued to keep their guns blazing while Egyptian artillery fire began to slacken throughout the afternoon. By mid-afternoon, white flags began to be hoisted over many of the battered Egyptian earthworks and forts. At 5:30 pm the British ordered a ceasefire. Black columns of smoke billowed from Alexandria. The city’s defenses were smashed. Trouble had been brewing with Egypt for some time, and war now seemed unavoidable.

Three years earlier, Prince Mohammed Ali Tewfik had become the new khedive of Egypt. As part of the Ottoman Empire, the khedive of Egypt was a vassal of the Ottoman sultan in Constantinople. Sultan Abdul Hamid had put Tewfik into power when he ordered him to replace his father, Ismail Pasha, who had ruled Egypt since 1863.

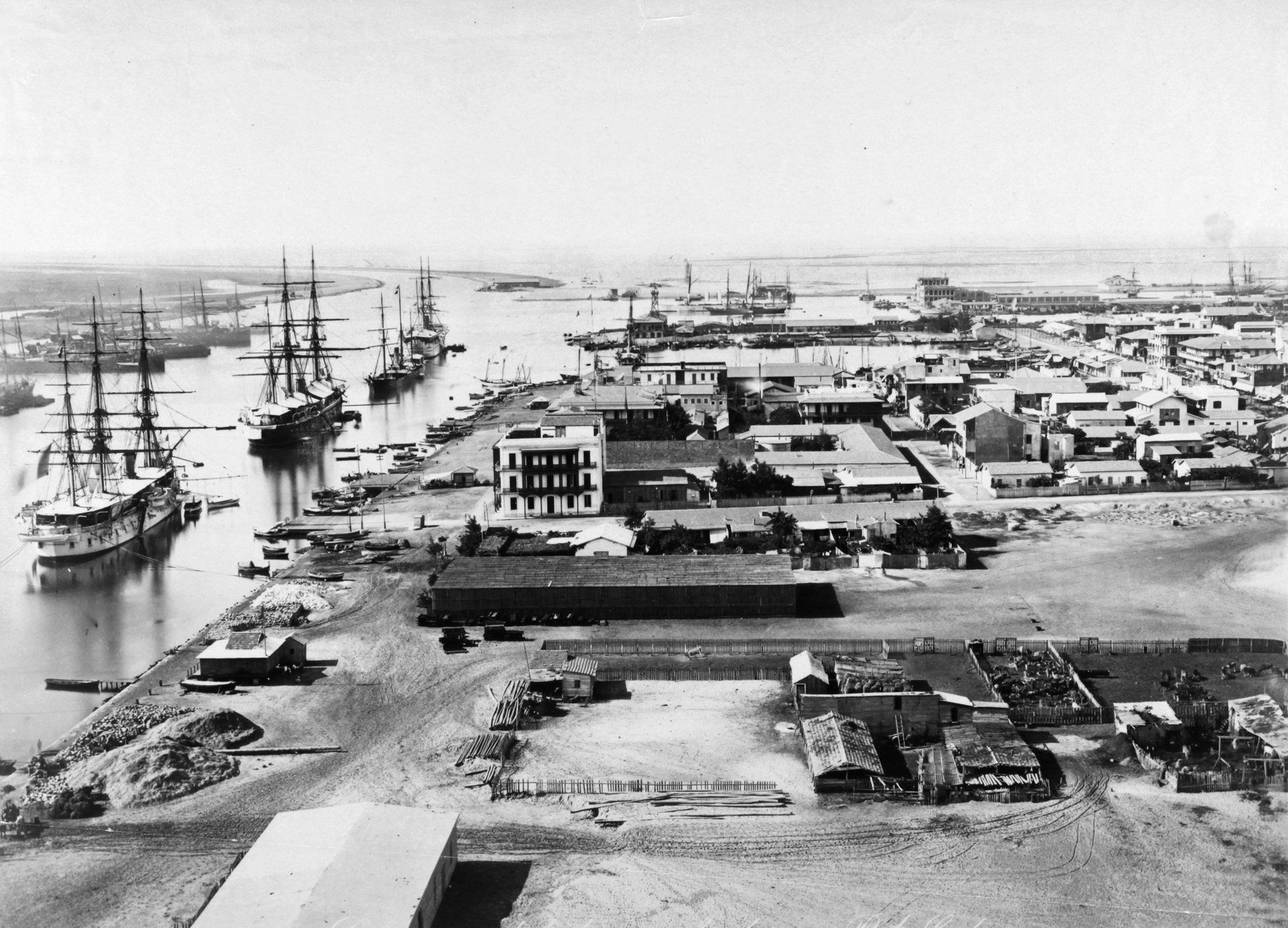

Ex-Khedive Ismail had grand designs for Egypt when he took power, setting on a program of large public works. He built hundreds of miles of railroad, scores of bridges, and thousands of miles of irrigation canals. Most importantly, he made key improvements to the bustling harbor at Alexandria. These projects, as well as military expeditions into Abyssinia, Somalia and Sudan, had nearly bankrupted the country. Egypt, which had financed the projects primarily with assistance from France and Great Britain, was heavily in debt to them.

Despite selling its interest in the Suez Canal to the British, Egypt remained mired in debt. In an attempt to get the earlier loans repaid to European creditors and restore Egypt’s credit, the khedive allowed Great Britain and France to establish dual control over Egypt’s revenues in 1877. The khedive did not fully cooperate with France and Britain, however, fearing the loss of his own authority. Thus, Egypt’s financial crisis remained a festering international problem.

Great Britain and France both had wanted Ismail Pasha to abdicate in favor of his son, and they were pleased when the sultan dismissed him. Ismail left Egypt for Naples aboard his yacht with as much treasure as he could take.

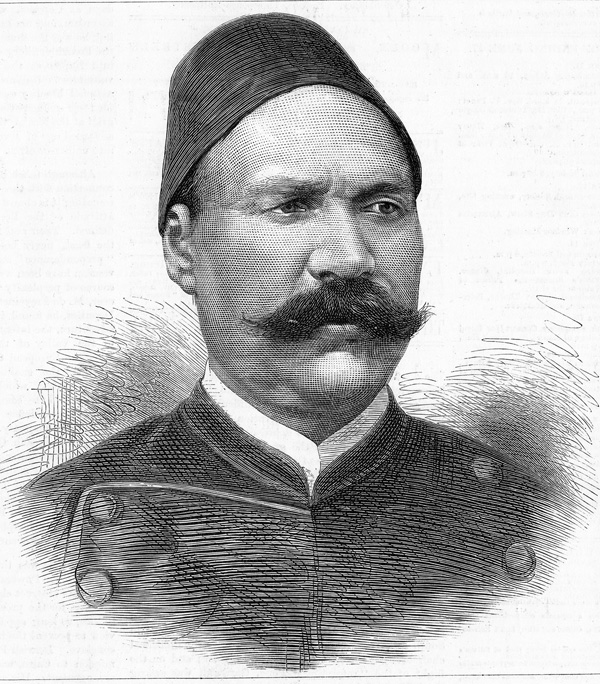

Once in power, Tewfik sought to bring stability and reform to Egypt. But he ran into difficulty trying to address the grievances of his senior military officers, who were displeased with cuts to the army. There were also hard feelings between the Turko-Circassian officers, who had controlled upper ranks of the military for many years, and the Egyptians, who held the lower ranks. Colonel Ahmed Arabi, a charismatic Egyptian nationalist, strived to address this imbalance.

Arabi led the army in a revolt in September 1881. The rebellious troops confronted Tewfik at his palace in Cairo, demanding that Tewfik appoint Arabi as minister of war. The British and French watched the upheaval with great concern. “[The] programme of Arabi is now pretty clear, and consists in the liberation of Egypt from European control,” British Consul-General Edward Malet warned Lord Granville, the British foreign secretary, in October 1881.

In an effort to maintain an alliance with France on the Egyptian’s problem, British Prime Minister William Gladstone agreed to send a so-called joint note to Egypt. This correspondence assured Tewfik that he had the sympathy of both England and France, and it encouraged him to maintain his authority. The two governments hoped the note also would curtail Arabi and the Egyptian nationalists, but it had the opposite effect: Tewfik was considered a puppet of Great Britain and France, and the joint note only served to embolden Egypt’s militant nationalists.

Tewfik’s authority gradually diminished as the months passed. Arabi became a pasha in March 1882. He acted like a dictator, and the nationalist movement grew stronger and more popular.

A combined British/French flotilla sailed into Alexandria’s harbor on May 20 seeking to bring the wayward Egyptians to their senses. Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Seymour, in command of the British squadron, was under orders from London to work with the British Consul-General, support Tewfik, and cooperate with the French. He had orders to protect British subjects and Europeans. If he believed it was necessary, he had the authority to put troops ashore.

Meanwhile, Egyptian soldiers and laborers began constructing earthworks with which to defend the harbor against the Europeans. Seymour cabled the Admiralty warning that the city was apparently under the control of the military party. “I think an increase of force desirable,” he wrote. “There is much panic at Cairo and some here.”

The panic increased substantially on June 11 in Alexandria. Rioting broke out as mobs attacked any European they could find. British Vice-Consul Charles Cookson did not escape the rage of the mob. Bloodied and badly wounded, Cookson stumbled to the police station, which was guarded by soldiers. The soldiers “did not move a step to protect me,” said Cookson.

The soldiers and police joined the inflamed mob. They traded fire with armed Europeans fighting for their lives. Dawn found many Europeans sheltering in various consulates throughout the city. The rampage had ended, but only after the mob had slain 50 Europeans. Over the course of the following days, thousands of Europeans fled to the coast and sought safety not only on commercial ships in the harbor, but also on the British and French warships.

The situation worsened in the days that followed. The British became deeply concerned over the security of the Suez Canal. By the end of June, the British hoped the Turks would intervene. “It was quite in the cards that the sultan will send troops after all,” noted Granville. Khedive Tewfik had at one point hoped for the same thing.

But the sultan had no interest in sending troops. British forces found themselves alone on July 5 when they were informed that the French fleet would not be aiding them. French Prime Minister Charles de Freycinet believed that it would be a violation of the French constitution to act in a hostile manner against Egypt without the consent of the Chamber of Deputies.

Seymour watched with growing concern as the Egyptians continue to construct earthworks and build new batteries in the port of Alexandria. On the morning of July 10, Seymour issued an ultimatum to the Egyptians that they were to temporarily surrender their forts and disarm. If they did not do so, he said, he would bombard their defenses.

The Egyptians held a war council. Both Tewfik and Arabi attended the council. They agreed to send a small delegation to Seymour informing him that no new guns had been mounted in the forts. The British Admiral was not interested; his demand to have the forts dismantled remained in place. The Egyptian War Cabinet decided that they would dismount three guns in three different positions in an attempt to appease Seymour. If this did not work, they sent orders for their guns to return the fire of the British after the fifth shot.

Seymour was not interested in having a small number of guns dismantled, and the deadline for the ultimatum continued to tick slowly down. On July 11, the flotilla that constituted the fighting element of Seymour’s squadron prepared to bombard the Egyptian forts and defences, which boasted 250 guns. Shortly after sunrise the ironclads opened fire. When the smoke cleared after a day of bombardment, the British had suffered five killed and 28 wounded. The Egyptians had suffered more than 100 killed and several hundred wounded.

Fires began to break out in the city, and the next day mobs again targeted foreigners. To everyone’s surprise, it was not the British who first landed troops in Alexandria to restore order. U.S. Marines from the USS Quinnebaug, anchored nearby, were sent into the tumultuous city to secure the American consulate and to extinguish fires in nearby buildings. Shortly afterwards, Royal Marines and sailors landed. They spiked the guns in three battered Egyptian forts and also tried to curtail looting and arson.

Tewfik, who had grown increasingly anxious about the situation, dispatched a message on July 13 to Seymour asking if he would guarantee his safety. Seymour agreed he would. As for Arabi, he began to reassemble part of the city’s bloodied garrison. He withdrew his troops to a strongly fortified position about eight miles east of Alexandria at Kafr-Dawar and took steps to increase the size of his force to 15,000 troops.

In his belief that the army should rule in Egypt, Arabi issued a proclamation four days later stating the British were to blame for the escalating violence. “[They] shot our soldiers and police who had been left in charge of the city,” he said. He then turned his scorn against Tewfik. “At night with his women amongst the English, and by day returns to the shore to order the unnecessary slaughter of Mahommedans in the streets of Alexandria.”

Meanwhile, British troop transports began disembarking soldiers. The British had 3,686 men ashore on July 18 under the command of General Sir Archibald Alison. The House of Commons voted to fund 2.3 million pounds sterling for an expedition to secure British interests in Egypt.

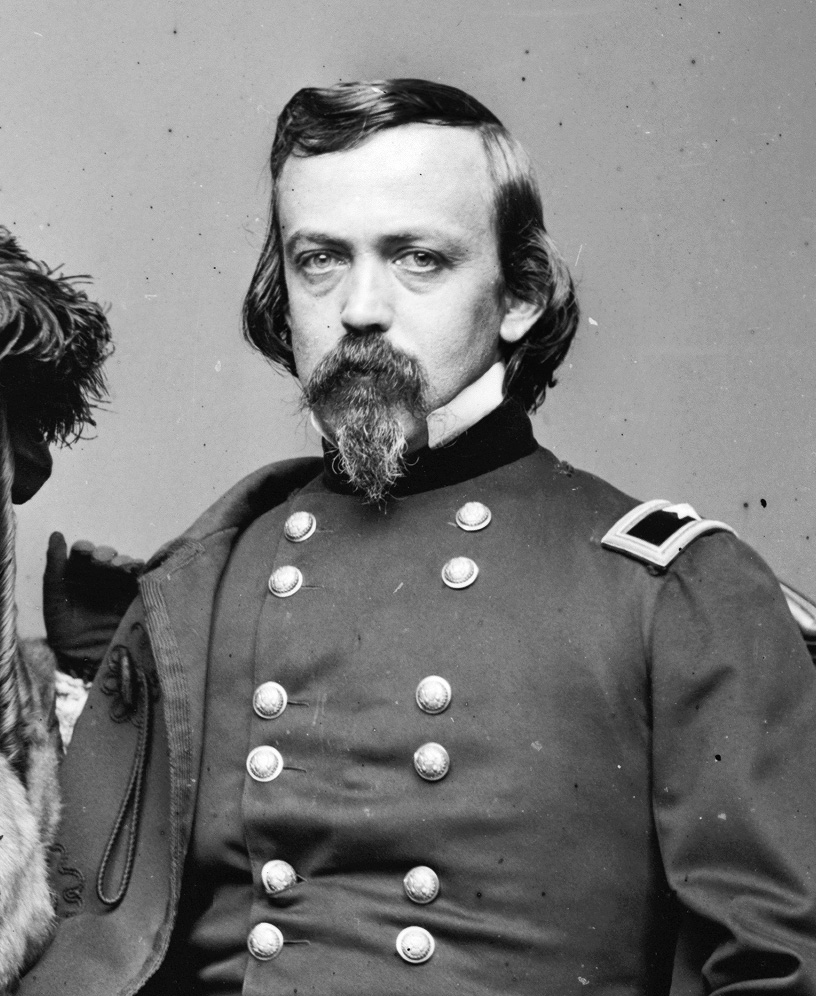

Lt. Gen. Sir Garnet Wolseley, the British Empire’s principal trouble-shooter, received command of the expeditionary force. The War Office had warned Wolseley in January that it might dispatch an expeditionary force to Egypt. Given this advance notice, Wolseley began making meticulous plans for the expedition.

Beginning in late July, infantry regiments and troops of cavalry embarked onto transport ships and sailed from England to Egypt. The British military authorities directed troops to pack artillery, siege trains, and supplies into the ships for the expedition. Other British forces embarked from outposts in Malta, Gibraltar, Cyprus, and even India to join the expedition. The expeditionary force ultimately numbered 40,500 troops.

Alison dispatched patrols in Alexandria toward Arabi’s entrenched position at Kafr-Dawar to determine his strength. Royal engineers deployed an armored train, which was manned by naval personal, to give the British direct fire support. Alison’s troops succeeded in capturing Ramleh on July 24, putting them in striking distance of Arabi’s position.

British expeditionary forces began disembarking at Alexandria in early August. Wolseley declared his intention to dispatch a large force to nearby Aboukir Bay to get behind Arabi’s position. He also intended to order a frontal assault from Ramleh. The Egyptians observed British troops re-boarding their ships, leading them to believe that perhaps the British were departing, but this was part of a grand ruse that Wolseley had instituted to deceive them.

Wolseley intended to send the re-embarked troops down the Suez Canal to Port Said and Ismailia. From there, they could strike out for Cairo. To speed his movement, the troops could use either a rail line or an inland waterway such as the Sweetwater Canal or Ismailia Canal.

British troops crowded aboard 17 transports just before nightfall on August 18. Escorted by eight ironclads, the transports steamed eastward. Upon reaching Aboukir Bay, which bristled with Egyptian guns, Seymour’s ironclads prepared for action. But the fleet succeeded in quietly slipping past Egyptian guns under the cover of darkness.

As Seymour’s fleet arrived at Port Said, sailors and marines from two Royal Naval vessels arrived first. A small detachment slipped into the port, where it surprised the sleeping garrison and took control of the northern end of the Suez Canal. Meanwhile, a larger naval detachment from four ships took control of Ismailia, which was situated midway on the canal.

The Seaforth Highlanders, an advance element of the Indian contingent, traveled in small boats down the Suez Canal on August 18. They received fire from 600 Egyptian reservists. The British returned fire with their Gatling guns, killing or wounding nearly one-third of the Egyptian force.

Most of Wolseley’s force had arrived at Ismailia by August 23. It was quickly discovered that the water level of the Sweetwater Canal, which ran west from Ismailia, was dropping fast. The Egyptians controlled the water level in the canal by a dam at Magfar. The canal originally had been constructed to bring freshwater to laborers working on the Suez Canal. Wolseley intended to use it as a supply line and dispatched Maj. Gen. Gerald Graham and his 2nd Infantry Brigade to seize the dam.

By this time, Graham was at the vital railway station of Nefiche, which he’d captured the day before. Reinforced by three squadrons of the Household Cavalry, a detachment of the 19th Hussars, mounted infantry, and a section of horse artillery, Graham moved out in the early morning of August 24. The force was accompanied by Wolseley, 1st Division commander Lt. Gen. George Willis, and staff officers.

After a gruelling march and dispersing enemy pickets, the British took control of the 70-foot dam at Magfar. They soon discovered the Egyptians were positioned on high ground at Tel-el-Mahuta, where they were reported to be guarding a second dam. Under an unrelenting sun that caused some of the troops to suffer from heat exhaustion, the British entrenched. Wolseley sent orders back for more troops to be rushed up from Nefiche. In the meantime, the Egyptians began shelling British position. In expectation of the coming ground action, they were reinforced by troops arriving by train from Tel-el-Kebir. A force of 8,000 Egyptian cavalry, infantry, and artillery prepared to advance against the British.

Redcoats from part of the 2nd Battalion of the York and Lancaster blazed away with their Martini-Henry rifles, checking the Egyptians’ advance. The Egyptians attempted to extend their line to the left but came under fire from British cavalry and mounted infantry. As the heat intensified, Egyptian gunners continued to shell the British with their six guns, with one shell barely missing Wolseley. The Royal Artillery section defiantly returned fire.

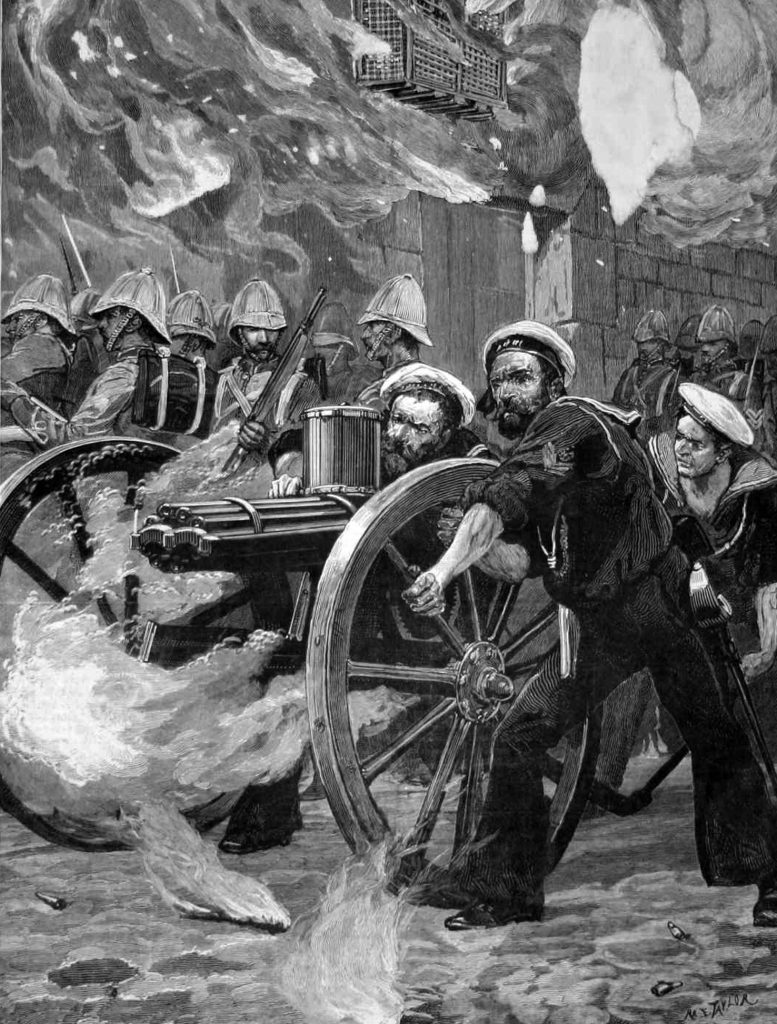

The Egyptians received six more guns, which joined in on the pounding of the British position. Around noon, sailors from the HMS Orion arrived with two Gatling guns, which were quickly placed on both British flanks. The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry arrived shortly afterward to strengthen Wolseley’s position.

Egyptian commander Rashid Pasha was reluctant to order an all-out assault; instead, he let his 12 guns pound the sweltering redcoats. The firing ceased at nightfall. The British advanced to the foot of the Tel-el-Mahuta, where they bivouacked for the night. During the night they received more infantry and artillery. After thanking his men for their actions, Wolseley returned to Ismailia to plan the next day’s attack.

On the morning of August 25, Graham advanced toward the Egyptian positions only to discover they had abandoned them and withdrew during the night. Wolseley ordered cavalry commander Maj. Gen. Drury Lowe to take his mounted troops and “work well round the enemy’s left and cut off his retreat, if possible.”

The heavy sand wore out Lowe’s cavalry horses and slowed their pursuit, except for the mounted infantry riding small Egyptian horses. Nearing enemy camp at Mahsama, the British horse soldiers soon found themselves facing a large force of Egyptian infantry and cavalry as well as seven guns. The British gunners quickly unlimbered and opened up on the Egyptians, while the mounted infantry dismounted and blazed away at close range with their Martini-Henry Rifles. With British infantry beginning to arrive and the cavalry threatening their line of retreat, the Egyptians retreated, abandoning seven guns in the process.

As one of the locomotives was gathering steam to pull away, Sergeant Patrick O’Riordan of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry sprang from his horse and dashed toward the train’s second car. He had noticed the car’s coupling was slack and undid it. As the engine pulled away, it left behind 20 cars, which were laden with ammunition and provisions. O’Riordan was later awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions.

Wolseley rested his exhausted troops at Mahsama for the rest of the day. That same day British cavalry reconnoitring the village of Kassassin captured Mahmud Fehmy, the chief engineer of the Egyptian Army, who had been left behind by his train. Fehmy had designed the entrenchments at Tel-el-Kebir, the main Egyptian defense protecting Cairo from an enemy advancing from the Suez Canal.

On the morning of August 26, the 4th Dragoons found the Kassassin Lock abandoned and quickly occupied it. The British hold here was strengthened with the arrival of Graham’s Brigade later in the day. Kassassin Lock was vital to Wolseley’s supply line as it allowed for the passage of boats. In the interim, troops near Mahsama continued to dismantle the two dams blocking the Sweetwater Canal.

Egyptian cavalry was spotted in the hills near Graham’s position by the canal lock on August 28. Graham had under his command the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, York and Lancaster Regiment, and elements of the 4th and 7th Dragoons. He also had 70 mounted infantry and guns from the Royal Marine Artillery and Royal Horse Artillery. The forces totaled 1,895 men.

The British fired on the enemy cavalry, and the Egyptians opened up with their guns. Nothing serious developed until the late afternoon, when white-uniformed Egyptian troops began advancing on the British position. Reinforced by two more guns, the British artillerymen pounded away at the Egyptians until their guns ran out of ammunition.

A captured Egyptian Krupp gun, which the British had mounted on a railway car, blazed away at the enemy. The Egyptian artillery attempted unsuccessfully to silence the gun. The Royal Marines manning the gun moved the railway car on which it was mounted back and forth along the railroad track to make it hard to hit.

When the Egyptians came to within 900 yards of Graham’s position, the British troops opened up a heavy fire. The Egyptians returned fire. They attempted to exploit a gap between the Royal Marine and the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, but the British infantry drove them back. The situation grew serious for the British as Egyptian reinforcements continued to arrive by train. The Egyptians attempted a flank attack shortly before nightfall against Graham’s left, but British rifle fire stopped them cold.

Graham received much-needed reinforcements when a battalion of Royal Marines arrived along with six more guns. He then ordered his sweat-soaked redcoats forward in the gloaming. Drury-Lowe arrived two miles northwest of Kassassin during the night with his worn-out cavalry. The British horse soldiers could see the night lit up by the flash of rifle fire at Kassassin and hear the roar of artillery fire. Their commander led them toward the flashing guns.

Enduring enemy fire, Drury-Lowe ordered his Household Cavalry to charge. He directed the 7th Dragoons to support them. British horse soldiers thundered with drawn sabers into the ranks of the Egyptian soldiers. They cut many down, and the survivors scattered. “The enemy’s loss was heavy, the ground being strewn thickly with their killed,” said Drury-Lowe. By nightfall, the Egyptians were in full retreat, leaving hundreds of dead and wounded behind them. The British suffered 10 killed and 80 wounded.

In the days that followed, the British received badly needed reinforcements. At Alexandria on August 29, Alison received orders to move his 1st Highland Brigade to Ismailia. Three days later the kilted soldiers arrived at their destination by ship, but it be would over a week before they started heading inland. In the interim, the British off-loaded supplies and shipped them forward to the front lines by rail or canal.

Colonel Sir Redvers Buller, fresh from his honeymoon, arrived at Kassassin to take command of the army’s intelligence. He was soon scouting the enemy entrenchments, sketching a map, and observing the Egyptian activities at daybreak.

While scouting in the early hours of September 9, Buller suddenly encountered a large Egyptian force on the move. Led by Ali Fehmy Pasha, the force consisted of 17 infantry battalions, various Bedouin units, and 30 guns. Arabi, who had been present during the attack on Kassassin on August 28, accompanied the force.

Buller spurred his horse back to camp with news of the enemy’s advance. A detachment of the 13th Bengal Lancers next met the Egyptian cavalry. Two riders were dispatched back to Kassassin with a warning, while the remaining 50 Lancers dismounted and took up position behind a ridge. They opened up with their carbines on the Egyptians, who soon surrounded the plucky band of Lancers. The Lancers quickly mounted up and, putting their lances to bloody use, charged through the enemy before galloping back toward camp.

Egyptian trains packed with troops arrived from the interior. Shells were soon exploding in the British camp. “Got them within reach at last,” Graham said to an aide as he watched the enemy troops arrive. Graham deployed his troops and prepared for action. The 1st Cavalry Brigade and the Indian Cavalry Brigade threatened the Egyptian left flank.

Graham ordered the Royal Marines, Royal Rifle Corps, and the York and Lancaster Regiment to advance in the early morning. The two sides traded volleys. The British infantry engaged was soon reinforced by three more regiments. Although outnumbered, the crack British troops gained the upper hand. By late morning, the Egyptians were in full retreat back toward their lines at Tel-el-Kebir. When Wolseley arrived on the field, he ordered a halt to the pursuit, not wanting to attack the enemy’s main position with only part of his overall force.

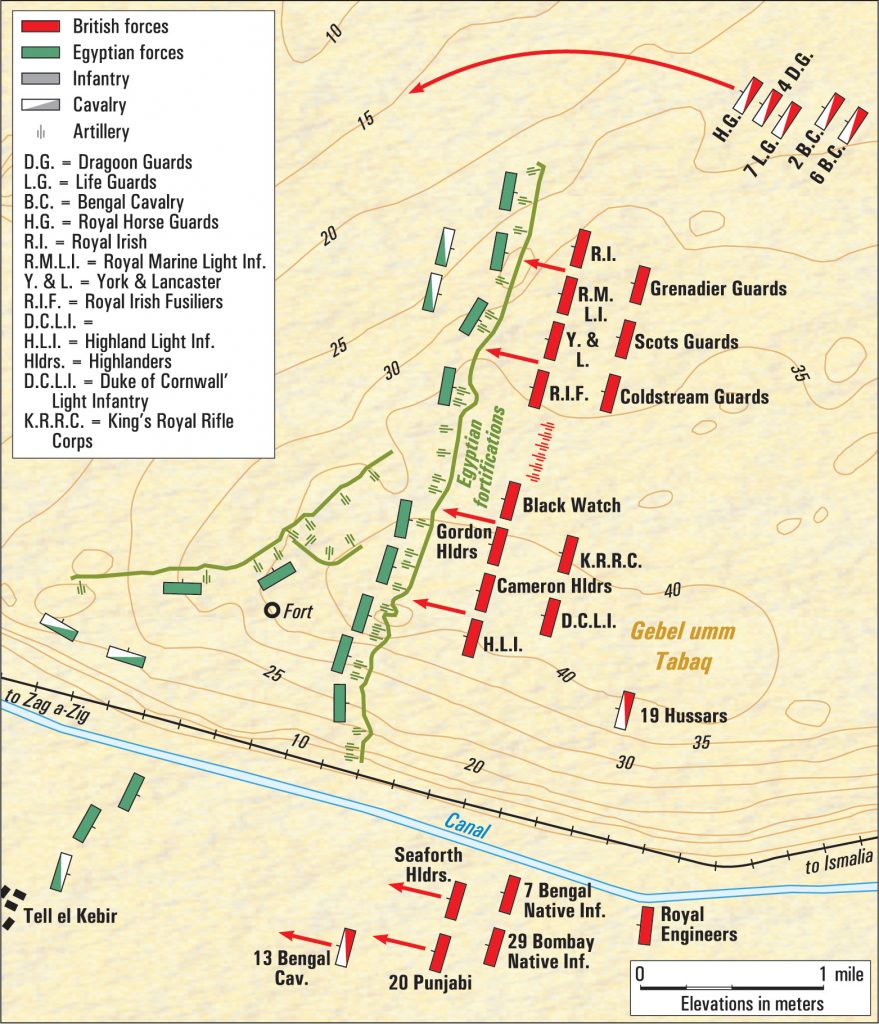

Wolseley intended to keep the pressure on the Egyptians. At dawn on September 12 the British commander led a group of senior officers and staff on a reconnaissance of the main Egyptian line. The enemy’s line of entrenchments stretched for four miles from the canal north into the desert. The Egyptians had buttressed their defensive line with nine batteries. In front of the entrenchment was a deep ditch. Connected to these entrenchments were trenches leading to gun redoubts, many of which supported the center and right of the main line. Egyptian engineers had built redoubts on either side of the canal to guard a dam and a rail line.

In addition, the Egyptian left flank was dotted with hilltop batteries to guard against enemy attempts to outflank the position. On the opposite side of the canal, the Egyptian right flank was protected to some extent by the soft soil of cultivated ground that prevented the passage of batteries. The village of Tel-el-Kebir was situated on this side of the canal.

Arabi had 28,000 troops, among which were Bedouins, and upwards of 75 guns to hold these lines. But the majority of the Egyptian troops were raw recruits. Arabi’s most professional troops were the Sudanese regulars.

As for the British, Wolseley had on hand 17,000 troops and 61 guns with which to assault the Egyptian entrenchments. He intended to launch a surprise attack at dawn. He and his officers conferred over their plans as they observed the enemy. They took careful note of the enemy’s picket positions and made final plans for an attack the next day.

Wolseley intended to make a night march to get into position to strike the center and left of the Egyptian line. The old soldier correctly surmised that the Egyptians would concentrate most of their guns on their right near the canal.

“Go straight in on them, and then kill them all,” Wolseley told his subordinate commanders. The officers subsequently issued orders to their respective units that afternoon to prepare to advance at 6:30 p.m. As a precaution to deceive the enemy, they left their campfires burning. After piling their baggage for safekeeping by the rail line, the soldiers proceeded to prearranged points in preparation for a six-mile night march. As they headed out into the darkness, each man carried 100 rounds of ammunition, two days’ worth of rations, and water bottles filled with cold tea.

Lt. Gen. Sir Edward Hamley’s 2nd Division anchored Wolseley’s left north of the rail line. Alison’s 1st Highland Brigade led the way and was followed closely by Colonel C. Ashburnham’s 4th Brigade. Willis’1st Division, spearheaded by Graham’s 2nd Brigade, took up a position 1,200 yards to their right. Marching behind them was the 1st or Guards Brigade under the command of Maj. Gen. Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, who was Queen Victoria’s third son.

Between the Guards Brigade and the 4th Brigade were seven batteries. Two Royal Horse Artillery batteries deployed to the right of the Guards Brigade. Drury-Lowe’s cavalry division advanced on the far right of Wolseley’s force. The railway gun situated on tracks in the left rear of these forces added additional firepower.

The Indian contingent under Maj. Gen. Sir Hebert Macpherson deployed on the south side of the Sweetwater Canal. Sailors manning six Gatling guns took up a position on the north side of the canal. Macpherson had orders to advance an hour after the rest of the force. Wolseley had deliberately delayed their advance, for there were villages nearby and he did not want the Egyptians to have any advance warning of the main attack.

Wolseley’s force advanced steadily through the night. “Considering the intense darkness and the excessive strain on everybody, that the army kept together as well as they did,” wrote Robert Tutt of the Royal Marines Light Infantry. As the troops closed in on the Egyptian entrenchment halts were made to realign and reform the men, especially in Alison’s Brigade.

The British troops’ attention suddenly turned to a comet streaking across the eastern sky at 4:50 am. Not long after this cosmic event occurred, rifle fire broke the morning silence as an Egyptian cavalry patrol bumped into part of Graham’s Brigade. As light began to appear on the eastern horizon, Alison’s Highland Brigade quickly discovered that they were just 350 yards from the enemy’s line. As bullets began to zip through the air, Alison ordered his Highlanders to fix bayonets. A bugle blast signalled the attack, and the Highlanders let out a rousing cheer and charged.

The Highlanders endured a wall of fire as they struggled forward in two waves. The Highland Light Infantry on the left ran into a deep ditch and straight into the galling fire from enemy troops from behind a protected position. The Black Watch on the right also ran into trouble when it encountered earthworks and murderous fire. But it was the Cameron and Gordon highlanders in the center that had the distinction of reaching the enemy line first.

The British units furthest in front soon found themselves taking fire from three sides. Some of the men were on the verge of withdrawing when Alison appeared revolver in hand to help rally the men. Hamley arrived with much-needed support to strengthen the Highlanders and enable them to hold captured ground. At that point, the Highland Light Infantry and Black Watch stormed the enemy’s earthworks and redoubts. “The bayonet was the only thing we used, and we used it right well,” said Lachlan McLean of the Black Watch.

To Alison’s right, Graham’s Brigade attacked shortly after the Highlanders. The infantry raced across 900 yards of ground. The air was hissing with lead as the Royal Irish Fusiliers, the York and Lancaster Regiment, and the Royal Marines fought their way into the enemy trenches. Some of the Egyptians fled. The British infantry bayoneted or shot those who attempted to hold their ground. The confusion stalled the advance. “It took me a long time to get the men in hand again,” said Lt. Col. Jones, who commanded the Royal Marines.

The cavalry on the far right went into action at 4:40 am. Fifteen minutes later they were 2,000 yards away from the Egyptian line. They took fire from a fortified position on the Egyptian left, which was soon silenced by a battery of the Royal Horse Artillery.

The cavalry continued their advance, swinging around the enemy’s flank in order to get behind the Egyptians. The Egyptians found themselves in a desperate position. The combined force of Graham’s Brigade, the Highland Brigade, and the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry forced back the Egyptians. After overcoming fierce resistance in the main entrenchments, the Highlanders had a tough time dislodging the Egyptian troops who fought furiously to hold a second line of trenches. The Highlanders captured the second line of trenches at 6:00 am.

Meanwhile, the British guns had moved into the captured enemy lines and were sending shells into the beleaguered Egyptians. With the red-coated British infantry proving unstoppable, the Egyptian’s left flank gave way. A group of white-clad Egyptian troops fled. British cavalry and horse artillery gave chase.

The situation was little better on the south of the canal, where the Indian Contingent launched its assault. Enduring screaming shells and whizzing bullets, the Seaforth Highlanders took an enemy battery and captured a dozen guns. At the same time, the 20th Punjab Native Infantry took a nearby village supported by another Indian regiment, which maintained a steady fire against a large force of Bedouins.

North of the canal, the Highland Brigade pushed on with lead elements climbing over hilly ground to spot the enemy’s camp. They could see thousands of enemy troops scurrying about and trains preparing to steam out of the railway station. Moving toward the camp they were met by the Egyptian commissary-general with a white flag asking to be taken to the British headquarters. The British had the Egyptians in full retreat shortly after dawn.

When the smoke of battle cleared the British had suffered 58 killed, 401 wounded and 15 missing. The Egyptians, on the other hand, suffered about 2,000 killed, an unknown number wounded, and 3,000 captured.

Wolseley drove his forces onward in a bid to prevent Arabi, who had fled the front for Cairo, from gathering more troops. The Indian Contingent hurried onto the village of Zagazig, where it cut the rail line to Cairo and severed Arabi’s communications with his forces in the field. Wolseley directed his cavalry to advance to Cairo.

By mid-afternoon the cavalry and mounted infantry reached Belbeis after a 30-mile ride. Upon reaching the town, they took a much-needed rest before swinging back in the saddle on September 14 to continue their advance. That afternoon they reached the outskirts of Cairo. Drury-Lowe dispatched 50 troopers under Lt. Col. Herbert Stewart to capture Abbassiyeh Barracks on the edge of the city. The troops from the barracks promptly surrendered.

A small force of the 4th Dragoons and mounted infantry under Royal Engineer Captain Charles Watson continued into Cairo, where they accepted the surrender of the 10,000 troops garrisoning the city. Arabi surrendered unconditionally that night to Drury-Lowe. This brought the short but bloody Anglo-Egyptian War to an end.

Wolseley had shown great professionalism in the way that he brought the campaign to a speedy conclusion. On September 25, Tewfik was back in Cairo. As for Arabi, he was tried on December 3 and sentenced to death, but his sentence was commuted, and he was exiled to Ceylon.

The British restored power to the Khedivate, and most of the troops in the expeditionary force departed in November. But an occupation force remained to protect Great Britain’s interests and prevent another war. The British celebrated their triumph over the Egyptians on November 18 when the victorious troops returning from the battlefront marched past Queen Victoria in London.