By John Brown

In the late 18th century, the French established Catholic missions in Indochina, and until the 1820s they enjoyed local protection, but after that persecution began and increased steadily, particularly under Emperor Tu-Duc, who reigned from 1847 to 1883 and wanted to stamp out Christianity. Emperor Napoleon III of France did not intend to let that happen, and in 1858 he began sending French forces into the Saigon delta. In 1862, Tu-Duc was forced to sign a treaty granting religious toleration and conceding some of his territory, including Saigon. From this nucleus the French expanded into the rest of Indochina.

Resistance to French occupation was mainly in the northernmost province, Tonking. In August 1883, French Admiral Courbet bombarded rebel-held forts at the mouth of the Hue river “inflicting fearful loss of life” and a treaty was extorted providing for a French protectorate over the whole of Indochina which included present day Vietnam (traditionally composed of the three kingdoms of Cochin China in the south, Annam in the center and Tongking in the north) and Cambodia and Laos.

The French then sent expeditions against the north, but this brought China into the contest, for Peking claimed a loose suzerainty over Indochina and did not want its enemy France (from the Second China War) on its border. China began planning for a war against the French. Courbet was eager for full-scale hostilities, but France was too insecure in Europe for outright war and chose to try to eliminate guerrilla warfare in the north.

Then, in June a three-day battle near Bacle, in which Chinese troops took part, resulted in a defeat for the French. But the French pushed on, enveloping one strongpoint after another, forcing the rebels to retire. To strike terror, all prisoners including wounded soldiers and civilians, were executed. Labour was forcibly requisitioned and harshly treated, resulting in a mass flight of coolies and a consequent shortage of carriers to take provisions and ammunition to the fighting units. In March 1885, French General Oscar de Negrier was wounded and defeated at Langson near the frontier, and the French withdrew en masse.

The Chinese did not follow up this victory, and the French were allowed to regain lost ground. In June, the Treaty of Tientsin gave the French most of what they wanted. From then on they ruled Indochina with an iron fist, putting down insurrections savagely, making much use of the Foreign Legion and troops from France’s North African possessions until the beginning of World War II.

The Fall of France, the Rise of the Viet Minh

France fell to Nazi Germany in 1940, and the Japanese, taking advantage of this, raided Indochina’s borders and threatened to bomb Hanoi while making demands for military bases in Indochina. The French administration capitulated, and the Japanese moved in. They left the local administration to continue its rule much as before while they concentrated on building air, naval and military bases throughout the country in preparation for further expansion in the region. They looted the country of its agricultural and mineral wealth and closed an overland supply route to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists in China which ran through Indochina from the port of Haiphong.

French humiliation at the hands of the Japanese emboldened Indochinese nationalists, most of them communist-led, to begin a series of insurrections against French rule. One of them was a nationalist party founded in 1941 by Nguyen Ai Quoc, who changed his name to Ho Chi Minh (“He Who Enlightens”). At a conference of a number of nationalist groups, he formed the League for the Independence of Vietnam (Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi), soon shortened to Viet Minh.

The insurrections were ruthlessly put down by the French with many villages and small towns put to the torch and thousands of Indochinese killed, maimed, or imprisoned. Long lines of prisoners were seen in Saigon, tethered together by wire pushed through the palms of each man’s hands.

How to Restore the Colonial Order?

With the end of World War II in the Pacific, the intention of the Allies was to return to the colonial position as it existed before the Japanese invasion. The British objective for Indochina was to drive out the Japanese and return it to the Free French led by General Charles de Gaulle, but the American attitude was quite different.

At the time, America was hostile to colonial restoration in general and to the restoration of French colonial rule over Indochina in particular. President Franklin D. Roosevelt made it clear he had no sympathy for the French and their empire. “France,” he said, “has had Indochina and its 30 million people for nearly a hundred years and the people are worse off than they were at the beginning.”

Roosevelt proposed that French rule should be replaced by a trusteeship that would prepare the way for independence. But American non-involvement in colonial restoration did not last for long, particularly when it became apparent that insurgencies in Indochina, Malaya, and the Philippines, were using Chinese communist methods of revolutionary warfare. By late 1946, in American eyes, a spread of communism was more dangerous than Western involvement in the Far East.

Emperor Bao Dai, Ho Chi Minh, and the Japanese Coup in Indochina

In March 1945, the Japanese, in response to their deteriorating military situation elsewhere and fearing an American landing in Indochina after the fall of Manila, staged a coup d’etat in Indochina. They disarmed and imprisoned French troops and proclaimed Indochina independent of France. Some French troops resisted and tried to fight their way to China, appealing to the Allies for help. The British wanted to help, but the Americans, much better placed to do so, refused.

In the south, the Japanese set up a puppet government under the Emperor Bao Dai, while in the north the communists set up the Provisional Revolutionary Government and a National Liberation Army with the clear intention of taking power once the Japanese had been defeated. By the summer of 1945, Viet Minh forces had liberated six northern provinces and parts of four others, had established local administrations, and were building up their military strength.

In the south, communist-led nationalist parties in Saigon quickly moved to seize the organs of government, liquidating or intimidating their rivals as they did so. While the Allies stated that the French had sovereignty over Indochina, American policy in practice was to oppose the return of French possessions to them. There was no official American animosity toward the communist-led Viet Minh groups, and the Americans actually provided assistance to them through the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

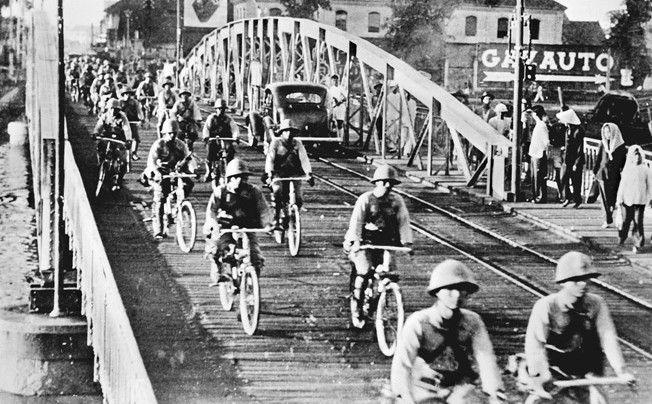

As Japanese defeat became more obvious, General Vo Nguyen Giap, Ho Chi Minh’s guerrilla leader, moved his forces towards the Red River delta, and when the Japanese surrender came in August 1945, he and his guerrillas were the only ones on the spot to take advantage of the situation. French troops had been disarmed by the Japanese since March, and so, on August 17, there was nothing to stop Giap raising the red flag with its yellow star all over Hanoi. He took over administrative authority on behalf of the Viet Minh and also took possession of the Japanese and French arsenals, providing him with some 60,000 rifles, 3,000 light machine guns, some artillery and a large supply of ammunition.

Dividing Indochina for the Post-War Order

For the Allies, Indochina was included in the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations under the leadership of Chinese Nationalist General Chiang Kai-shek with whom the Americans had two military advisors, Generals Albert C. Wedemeyer and Joseph Stilwell, who naturally shared the anti-colonial views. At one point it looked as though the colonial French Army, before it was disarmed in 1945, would stage a coup against the Japanese. Officers of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), called Force 136 in Asia, were trying to make contact with the colonial French Army to give them advice, supplies and encouragement. Wedemeyer got news of it and said it was a misuse of Lend-Lease equipment and that if the operation did not cease the equipment would be withdrawn.

At Potsdam in July 1945, the Allied leaders divided Indochina in half at the 16th parallel and decided that Chiang Kai-shek would accept Japanese surrender north of the parallel and return the territory to France and Lord Louis Mountbatten, British Commander-in-Chief, South East Asia Command, would accept Japanese surrender south of the parallel and restore French rule there.

Mountbatten formed an Allied Control Commission based in Saigon. It would have an infantry division to maintain civil order in and around Saigon while the commission itself would be concerned primarily with winding down the Supreme Headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army in Southeast Asia and rendering humanitarian aid and assistance to Allied prisoners of war and internees. Major General Douglas Gracey was named to head the mission and take with him his crack 22,000 strong 20th Indian Division.

“All Men Are Created Equal”

Upon Japan’s surrender, Viet Minh forces consolidated their hold over the north, and with Hanoi in his hands on September 2, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, reading out to a huge crowd of people in Hanoi the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence.

He cited the American Declaration of 1776: “All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among them are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

He went on: “The whole Vietnamese people, animated by a common purpose, are determined to fight to the bitter end against any attempt by the French colonialists to reconquer their country. We are convinced that the Allied nations which at Tehran and San Francisco have acknowledged the principles of self-determination and equality of nations, will not refuse to acknowledge the independence of Vietnam. A people who had courageously opposed French domination for more than 80 years, a people who have fought side by side with the Allies against Fascists during these last years, such a people must be free and independent.”

The Communist Revolution in Saigon

While the communists were consolidating their hold over the north and establishing a stable government with broad support in Hanoi, in the south their influence was not so strong. In Saigon there were a number of nationalist and socialist organizations competing for influence and power. On August 21, the United National Front organized a large militant demonstration in Saigon, bringing together the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao organizations and the city’s strong Trotskyist movement. This was a show of strength by those critical of communist policy and indicated that here in the south the Viet Minh would not have it all their own way.

On August 25, the Viet Minh organized their own much larger demonstration in Saigon and established the Committee of the South as a revolutionary government. The committee, headed by communist leader Tran Van Giau, attempted to establish control over Saigon and to extend its influence throughout the rest of the south.

On September 2, during another massive communist demonstration in Saigon, five Frenchmen and a number of Vietnamese were killed. Several French suspects were arrested but were later released at the insistence of the Committee of the South; the communists were determined to avoid anything that might turn the Allies against them. They were not preparing to fight British forces on their way to occupy Saigon. They hoped to be able to work with them.

MacArthur’s Delay

Some British forces were already at sea, heading for Indochina when General Douglas MacArthur caused confusion by forbidding the reoccupation of Indochina until he had personally received Japan’s surrender in Tokyo, set for August 28. A typhoon caused the ceremony to be postponed until September 2.

MacArthur’s order meant that prisoners of war remained in the hellish conditions of their prison camps for longer than was necessary, and the additional delay before British troops arrived enabled revolutionary groups to fill power vacuums that had existed since the announcement of the Japanese capitulation on August 15.

MacArthur had his ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, and British medical teams began parachuting into prison camps. An advance party of support personnel with an escort of troops from Gracey’s force arrived in Saigon to check on conditions and report back, and on the 11th the first brigade of the 20th Indian Division began flying in from Burma via Bangkok. These advance units were welcomed by fully armed Japanese and Viet Minh soldiers. The full division was not in place until the end of October.

Restoring Order in South Vietnam

General Gracey arrived in Saigon on September 13. He was faced with anarchy and chaos in a city where murder was commonplace. Administrative services had collapsed and a loosely controlled, communist-led revolutionary group had seized power—their soldiers were guarding all vital points in the city including Gracey’s own office building. The Japanese were still fully armed, bad weather was slowing down the fly-in of Gracey’s Indian Division, and on top of it all he could not communicate with his headquarters in Burma as, at the last moment, his American signals detachment had for political reasons been withdrawn by the United States. Replacement would take weeks.

On his arrival, Gracey was approached by the Committee of the South, but he refused to have any dealings with them. He was interested only with the Japanese military authorites and the French. He warned that unless something was done quickly the state of anarchy would worsen with the Viet Minh’s lack of control over some of their allied groups.

Gracey’s refusal to recognize the existence of the Committee of the South completely undermined its conciliatory position, forced the communists into confrontation, and strengthened the position of those who advocated armed resistance.

On September 17, the committee tried to compel Gracey to recognize it by imposing a boycott of the French, calling a series of strikes and ordering the closure of the Saigon market to cut off food supplies to the city. Gracey decided that the committee must be crushed, and on September 19 he closed down the Vietnamese press and took control of Saigon radio. He banned all demonstrations and meetings in southern Indochina, prohibited the carrying of weapons, reimposed the Japanese curfew regulations, and introduced the death penalty for a range of public order offenses. In effect, he declared martial law.

The French Coup

Gracey was persuaded by the French to rearm the soldiers of their local Colonial Infantry Regiment who were being held as prisoners and would evict the Viet Minh from the hold they had on Saigon. He saw this as the quickest way to allow the French to reassert their authority while letting him get on with disarming and repatriating the Japanese, of whom there were some 35,000.

During the next few days, the Viet Minh were eased from their grip on Saigon. Gracey replaced their guards on vital points with his own troops, who gave way to the French as the Viet Minh would never relinquish their positions directly to the French. By September 23, the French had regained control of the city, and then Gracey allowed 1,000 French former prisoners to be rearmed. Aided by the Colonial Infantry Regiment, they ejected the Viet Minh in a coup in which only two French soldiers and no Vietnamese were killed.

The French commissioner, Colonel Henri Cedile, now had some 1,500 well armed soldiers under his control, and he used them to stage a coup d’etat. The soldiers seized public buildings, arrested large numbers of Vietnamese (the committee escaped them), raised the French Tricolor over Saigon’s city hall, and the celebrations began. They soon degenerated into a pogrom with Vietnamese civilians insulted and beaten on the streets and in their homes. With this French coup, Gracey ended martial law and General Jacques Leclerc informed Lord Mountbatten, “Your General Gracey has saved French Indochina.”

Clashes Between the British and the Viet Minh

The Vietnamese reacted. On the night of September 24, a howling mob, not under Viet Minh control, abducted, butchered, raped and mutilated dozens of French and French-Vietnamese men, women and children. On the 25th, the Viet Minh attacked and set fire to the central market and attacked the airfield perimeter but were repulsed by Gurkhas.

For the next few days armed Viet Minh parties fought British/Indian patrols all over the city with the Viet Minh suffering mounting losses. Mortars, 25-pounder guns and heavy machine guns were used by the British in the street fighting. The British troops were highly experienced, having battled their way through Burma against the Japanese, and many officers and other ranks had experience in internal security and guerrilla warfare in India and on the North West Frontier. A British officer observed: “The Viet Minh were a courageous enemy, but were still learning about war.”

It was in this confused fighting that the OSS commander in Saigon, Lt. Col. Peter Dewey, was killed by the Viet Minh. He was probably mistaken for a French officer. The day after Dewey was killed, an OSS officer refused to intervene when Viet Minh troops arrested a French officer and executed him. The American declared he was neutral. Mountbatten protested to the Americans, but it appeared that they “were on the other side in this war.”

“For Two Pins I Would Have Turned the Guns on Them”

A report by a British artillery NCO gives some idea of the sort of situation a soldier might be faced with on patrol in Saigon at the time: “Sometimes we came across rebels, mixed groups of Japanese and Viet Minh. One group had taken over a bungalow close to Saigon that had been occupied by a French plantation manager; they had cut the throats of the man and his wife and children and then dug themselves in under the bungalow which was raised on stilts about two feet above the ground. They were two Japanese with machine guns and five Viet Minh with rifles and they were holding up the advance of a French-led colonial battalion of about 450 men. The French were badly trained, no discipline—awful colonial troops. They called on us to use our guns.

“We fired ten shells at 400 yards range, reducing the bungalow to rubble. By this time the French had decided to go in, so a whistle was blown and everyone was shouting and bawling and firing. We stood looking at them in amazement. We’d been used to the Gurkhas who went in like snakes through the grass. You never heard anything with them. What an army this lot were, bugles going and everyone shouting. In the melee the rebels escaped through the back of the bungalow.

“They left behind an old man who had survived the shelling. He was obviously a carrier, and he was terrified. The French were kicking and beating him. They said they were interrogating him, but you could see he didn’t know anything. Our battery commander, who spoke French, ran over and started to tell them what he thought of this. He was pushed aside and told to fight his war and let them fight theirs. He came back fuming.”

Meanwhile, a length of telephone wire had been fastened around the old man’s neck and the end of it thrown over a tree branch. “Our officer went over to them again; he was mad with anger and frustration. He came back and told me to limber up. ‘I will not stay and witness a cold-blooded murder’ he said as we left them. Later that day, he said: ‘For two pins I would have turned the guns on them’. If he had done so he would have been fully backed up by the troops. That was French Indochina. We were glad to leave later that year.”

While the British were trying to clear Saigon, the Viet Minh infiltrated soldiers into the outskirts of the city and established roadblocks that effectively isolated the city from the rest of the country.

Shattering a Fragile Peace

In early October, Gracey made contact with the Viet Minh and truce talks began. For the British the talks were a ploy to gain time for more troops to be flown in. On October 5, General Jacques Leclerc arrived in Saigon to take command of French forces; he and his troops would come under Gracey’s command. On October 10, the fragile peace with the Viet Minh was broken by an unprovoked attack on a British engineering party inspecting water lines near Tan Son Nhut. All members of the party were killed or wounded. This brought Gracey to accept the fact that the level of armed insurrection was such that he would first have to pacify key areas before he could afford to repatriate the Japanese.

Gracey’s second brigade, the 32nd of his 20th Indian Division commanded by Brigadier E.C.V. Woodford, had arrived to join his now built up first brigade, the 80th, commanded by Brigadier D.E. Taunton. His third brigade, the 100th, commanded by Brigadier C.H.B. Rodham, was due to arrive on October 17. On the day following the attack on the engineering party, Gracey deployed the 32nd Brigade into Saigon’s troublesome northern suburbs of Go Vap and Gia Dinh, and they drove the Viet Minh out of the suburbs.

On October 13, Tan Son Nhut Airfield came under a Viet Minh attack that came within 275 meters of the control tower, and they were at the doors of the radio station before the attack was blunted by Indian and Japanese troops with heavy losses for the Viet Minh. As the Viet Minh were pushed back from the airfield perimeter the Japanese, under British orders, pursued them until nightfall, killing more of them.

The fighting in and around Saigon took on the characteristics that became common later—ambush, assassination, hit-and-run raids, sweeps by security forces, and so on. This was the first of the modern unconventional wars and, although the Viet Minh had sufficient troops to sustain a long campaign, they were beaten back by well led professional troops who were not alien to Asia. By mid-October more than 300 Viet Minh had been confirmed killed by British, Indian, and Gurkha troops and 225 more by the Japanese. British, French and Japanese casualties were very small.

The Viet Minh concentrated attacks on Saigon’s vital points, on powerplants, docks, the airfield, and the city’s artesian wells. Saigon was periodically blacked out at night, and the sounds of small arms, grenades, mines, mortars and artillery became familiar. On one occasion the Japanese repulsed an attack on their headquarters at Phu Lam, killing more than 100 Viet Minh. Unable to overwhelm the city’s defenses, the Viet Minh intensified their siege tactics as the first troops arrived from France. They were used to help break the siege, while aggressive British patrols kept the Viet Minh off balance.

Lieutenant Colonel Gates and his ‘Gateforce’

On October 29 the British put together a task force with the objective of pushing the Viet Minh main units further away from Saigon. It was named Gateforce after its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Gates of the 14/13 Frontier Force Rifles. Gateforce was made up of Indian infantry, artillery and armored cars and a Japanese infantry battalion. In operations at Xuan Loc east of Saigon, between 160 and 190 Viet Minh were killed by Indian troops and 50 were killed by the Japanese, all the latter killed in a short action when the the Viet Minh were surprised while in training.

In another operation, in November, a Gurkha unit set out for Long Kien south of Saigon to rescue French hostages held there. En route they were attacked by units of Viet Minh, some of them led by Japanese deserters. At one point the Gurkhas were held up by Viet Minh who were occupying an old French fort. The Gurkas blew in a door with a bazooka and went in silently with only their kukris, putting all the defenders to the knife. They reached Long Kien that same day but were too late – the French hostages had been taken away.

The Last British Battle with the Viet Minh

In early December, Gracey turned over Saigon’s northern suburbs to the French with 32 Brigade handing over responsibility to General Jean-Etienne Valluy’s 9th Colonial Infantry Division. On Christmas day 32 Brigade left for Borneo.

Many of the newly arrived French soldiers were ex-Maquis (French Resistance), not accustomed to strict discipline, and many of them held Asians in disregard. It caused Gracey to write a blistering letter to General Leclerc, lashing out at those French who looked down on his Indian soldiers. He wrote: “Our men, of whatever color, are our friends and not considered ‘black’ men. They expect and deserve to be treated in every way as first class professional soldiers and their treatment should be, and is, exactly the same as that of white troops…. it is obvious our Indian Army traditions are not understood.”

The use of large numbers of Japanese troops against the Viet Minh outraged many British troops and caused an outcry in Britain, but Gracey found it necessary to supplement his inadequate forces and to minimize British casualties. Often, when fierce Viet Minh opposition was met, Japanese troops were sent to deal with it.

By the end of December, the British were ready to begin handing over the south to the French. The last battle between British and Viet Minh forces occurred on January 3, 1946, when about 700 Viet Minh, including a cadre of 200 from the north attacked the 14/13 Frontier Force Rifles positions at Bien Hoa. The fight lasted throughout the night, and when it was over 80 Viet Minh had been killed without the loss of a single Indian soldier.

In mid-January, with the Viet Minh now avoiding large-scale attacks on British forces, 80 Brigade handed territory over to the French and 100 Brigade withdrew into Saigon. Gracey left on the 28th. On his departure, control of all French forces passed to General Leclerc.

On March 30, 1946, the last two British/ Indian battalions left Indochina, leaving only a single company of the 2/8 Punjab to guard the Allied Control Commission in Saigon and a few specialist troops to assist the French. On May 15, the commission was disbanded and the Punjabis left. The last British soldiers to die in Indochina were six soldiers killed in an ambush in June.

For Britain’s Vietnam War the official casualty figures list 2,700 Viet Minh killed. About 600 were killed by British/Indian forces, the rest by Japanese and French. Given the efficiency with which the Viet Minh recovered their dead and wounded, the figures were probably two or three times those numbers. Forty British/Indian soldiers were killed. French and Japanese killed were substantially higher.

The Brutal British Operations

British military operations against the Viet Minh were conducted ruthlessly—it was conquest by force of arms of a hostile enemy city. In an operation instruction to the 20th Division, officers were warned that they would find it difficult to distinguish friend from foe and they should always use maximum force available to ensure the wiping out of any hostiles. “If one uses too much, no harm is done.” For the British, Indochina was not a “hearts and minds” operation.

Mountbatten was horrified when he learned that British soldiers were burning down people’s houses in reprisal for guerrilla attacks, and he complained to Gracey, “Cannot you give such unsavory jobs (if they are really military necessities) to the French?” Gracey replied that he considered the French much too undisciplined and trigger-happy to be relied on.

Without Gracey and his troops the French would probably have found it impossible to reestablish themselves in Indochina. The responsibility for the British intervention in Indochina lay with the Labor government in London which was involved at the time in the struggle to preserve European colonialism. From this point of view it was the British who started the Vietnam War and made it possible for the French to continue it, with American help, until their defeat in 1954.

The fighting from the latter part of the British intervention to the attempt by the French to restore their former rule had several unusual features. The first of these lay in the unusual demography of Vietnam. The vast bulk of the population was concentrated in two deltas, that of the Red River in the north and of the Mekong in the south. There was a thin band of fairly dense population along the eastern coast, but the great mass of the central highlands was very sparsely populated, and that mainly by hill tribes traditionally hostile to the Vietnamese. So the struggle for control of the Vietnamese people was concentrated in two areas that were far apart.

From Colonial Restoration to Dien Bien Phu

A second aspect was the situation of the French. They were, ostensibly, not fighting to retain colonial control but to establish autonomous states within the French Union. Their constant objective was to find an indigenous Vietnamese grouping that they could rely on to resist the Viet Minh and yet consent to remain within the French Union. There were many nationalists who had little cause to love the Viet Minh, and many of these were prepared to negotiate with the French.

The existence of many anti-Viet Minh groupings made the situation far more complex than a straight conflict between the French and the communists. There was a very important Catholic element in Vietnam with about 1.7 million followers. Their leaders tried to demonstrate that they were not necessarily pro-French, and they maintained their independence with the aid of their own militia.

Add to the mix of varied nationalists and religious groupings the hill tribes such as the Montagnards and the various large bands of river pirates who flourished on the Mekong, the situation in Indochina at the end of World War II was chaotic. In France, the Fourth Republic was notoriously unstable, and the presence of a strong communist minority in the legislature contributed to ambivalence about the future of Indochina. A comment popular in France at the time was that “the squalid little territory of Indochina is hardly worth fighting to preserve.”

The Indochina war that began with a win for Western forces in 1946 continued until 1954 when the loss of Dien Bien Phu after an epic siege of 55 days. The military catastrophe for the French resulted in the Geneva Conference in which France reluctantly conceded independence to all her territories in Indochina. But neither the new government of South Vietnam nor the United States were party to the agreement, and the Vietnam War continued until 1979 when peace finally came to the devastated land.

This is an anti-French narrative especially in its description of events prior to March 1945, and of what happened between March 1945 and the Japanese surrender.

Fighting from one colonialist to the another. All they want is to free themselves of these colonialist french and their iron fist.