By Cleve C. Barkley

Technical Sergeant Clyde Dugan flattened as another string of mortar shells ravaged the barren field. Pristine snow vomited fire and steel as chunks of frozen earth rocketed skyward then plunged to pelt his shoulders or clatter loudly on his helmet. Elsewhere someone screamed. It was December 13, 1944. This was the battle of Wahlerscheid Crossroads, Germany.

At the same time, a stream of neon tracers flashed overhead as machine-gun bullets sparked and rattled through the tangle of snagging wire in which he lay. Pausing briefly, Dugan summoned his courage then once again inched forward, wriggling beneath the sharp-tined obstacle as he led his squad toward the source of the terrifying tracers—a row of pillboxes that dominated the snowy plain.

After penetrating 40 yards of prickly wire, Dugan bellied into a narrow, mud-slicked trench. His squad, now reduced to eight, tumbled in behind him. Of the entire 9th Infantry Regiment, Dugan’s small command was the only one that even came close to reaching the enemy’s fortifications. The others, three full battalions, remained stalled 100 yards to the rear where they bled white amid the impeding wire.

Taking the Dams Across the Roer

In September 1944, the Allies were approaching the very threshold of Germany. Allied planning prior to D-Day called for a swift drive through the northern Cologne plain to deliver a crippling blow to the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany, and then a thrust to Berlin. However, after breaking the Normandy stalemate that summer followed by the madcap dash across France, the spearheading armored divisions literally ran out of gas. While the Allied tanks awaited fuel, the Germans regrouped and closed ranks behind their vaunted West Wall defenses, also known as the Siegfried Line, where they braced for the final assault.

By October, enough fuel, provisions, and ammunition had been stockpiled to continue the relentless drive into Germany. Although seven Allied armies were deployed from the North Sea to Switzerland, the shortest route to victory remained in the north where the Ninth U.S. Army had reached the western bank of the Roer River by December. While these forces marshaled for the inevitable river crossing, elements of First U.S. Army had become enmeshed in the hotly contested Hürtgen Forest, south of the city of Aachen. Hidden deep within the forest was a series of dams that controlled the current of the north-flowing Roer.

Initially, these dams received scant attention since it was believed that the enemy would not deny the Rhenish cities the power generated by their hydroelectric plants, but as strategists studied the terrain to the north they eventually concluded that if the dams remained under German control they would be capable of releasing devastating floodwaters, isolating any force crossing the Roer and subjecting it to piecemeal destruction. The largest were the Urft and Schwammenauel Dams, situated between Gemund and Schmidt in the heart of the Hürtgen. Combined, these two restrained 123,000 acre-feet of water, enough to inundate a 1,500-foot-wide swath of the northern lowlands with three feet of water. Before a river crossing could be attempted, the dams had to be neutralized.

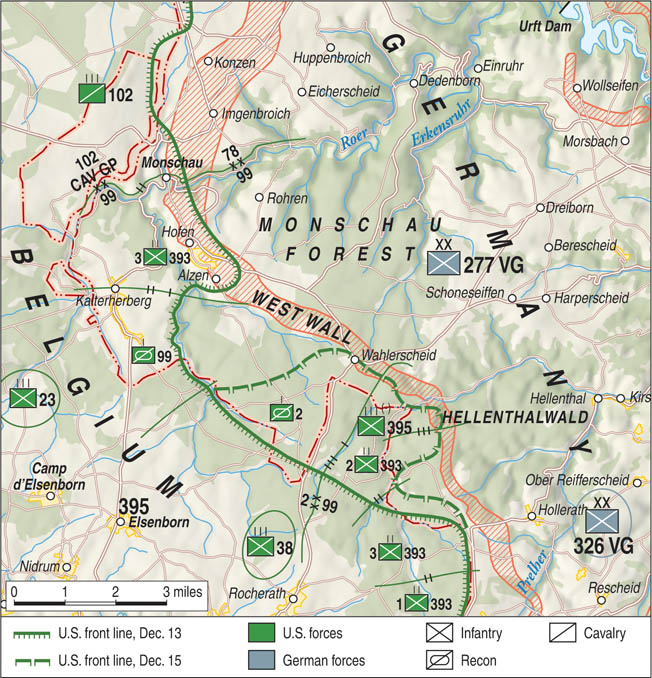

With the hope of producing breaches in the dams, several airstrikes were authorized in early December, but they proved ineffectual. As a result it was determined that they should be captured by overland assault. To achieve this, Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, commander of the U.S. V Corps, directed the newly arrived 78th Infantry Division to strike seven miles due east from the vicinity of Lammersdorf, Germany, to reach the Schwammenauel Dam, while 11 miles to the southeast Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson’s veteran 2nd Infantry Division would make a simultaneous attack northward from the Belgian border village of Rocherath to secure the Urft Dam.

Concerns With the Plan of Attack

Both units would be forced to crack the Siegfried Line before gaining good roads to their objectives. Stressing the importance of Robertson’s task, General Gerow had allocated seven battalions of corps artillery to supplement the division’s four artillery battalions. In all, some 120 field pieces ranging from 105mm to 240mm would be on call. In addition, three battalions of the 99th Infantry Division would launch supporting attacks to protect the 2nd Division’s right flank. The attack was scheduled for 8:30 am, December 13, 1944.

Relinquishing its sector of the Ardennes “Ghost Front” near St. Vith, Belgium, to the green 106th Infantry Division on December 10, the 2nd Division motored 15 miles north to Camp Elsenborn, near Rocherath. Colonel Chester J. Hirschfelder’s 9th Infantry Regiment had been selected to spearhead the division’s attack. The 9th, dubbed the “Manchu” Regiment after its role in the Chinese Boxer Rebellion of 1900, was an old Army formation with an unblemished war record. The Manchus were tasked with driving north through the underbelly of the Monschau Forest to take and hold a vital German crossroads called Wahlerscheid, four miles beyond Rocherath. Defended by elements of the 991st Regiment of Colonel Wilhelm Viebig’s 277th Volksgrenadier Division, Wahlerscheid was not a village but simply a forester’s lodge and customs house situated at a triangular road junction near the German-Belgian frontier. Once Wahlerscheid was secured, the 38th Infantry would make the main effort, swinging east-northeast to gain the open country at Dreiborn and then on to the Urft Dam.

From the outset, General Robertson had serious misgivings about his mission. Not only was his division to attack through terrain chillingly similar to that of the doggedly defended Hürtgen Forest, but the troops would also have only one road for resupply and evacuation of the wounded. The first concern was allayed by ensuring that the men carried sufficient ammunition and rations to sustain them over a 24-hour period without replenishment. The road, however, was a bigger headache. Known to be rife with roadblocks and mines, this solitary route would remain a tenuous link to Robertson’s forward units until the crossroads was secured and his forces had broken free of the restrictive forest. If severed by enemy counterattacks, the attacking battalions could easily be cut off and annihilated—a scenario that would nag him for the duration of the operation.

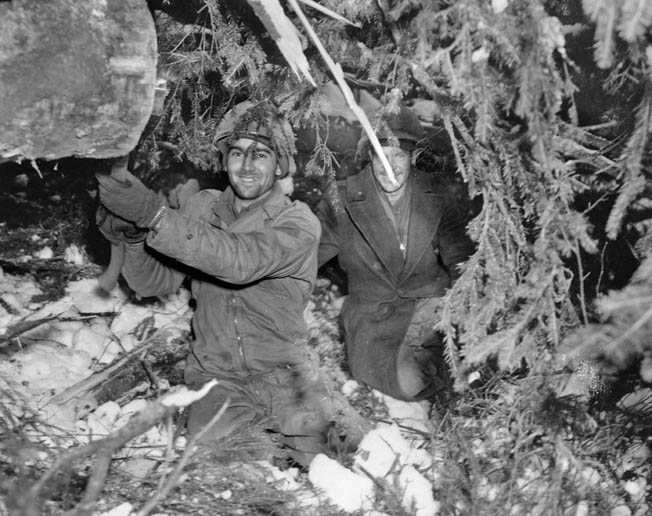

Scouting the German Lines

At daybreak on December 13, the 9th Infantry jumped off from its forward assembly area 2,000 yards north of Rocherath and entered the dismal forest. To preserve the element of surprise, there was no preliminary artillery barrage, and the attack proceeded in total silence. Avoiding the heavily mined road, Lt. Col. William D. McKinley’s 1st Battalion trudged to the left through shin-deep snow, while Lt. Col. Walter M. Higgins, Jr.’s 2nd Battalion did the same on the right. The 3rd Battalion trailed as reserve. Dense fog and winddriven snow restricted vision to 200 yards. Step by step, each soldier was forced to push aside heavy branches of the close-knit fir trees, triggering icy avalanches that plopped ungraciously onto helmets and shoulders or slid down raw red necks. As the morning progressed, a slight thaw melted the snow of the upper branches, initiating a constant drizzle. Before long, all were thoroughly soaked.

Initially, opposition was nonexistent. At times the leading scouts encountered German patrols, but apparently the enemy regarded the incursion as routine patrol activity that merited little more than a few discouraging mortar rounds. At one point, elements of Company H surprised a pair of Wehrmacht soldiers who seemed bewildered by the sudden appearance of the Americans. Immediately, one threw up his arms, but the other pulled a grenade and held it to his neck until it detonated. The sole captive later confessed that they were deserters, and his comrade feared that the Americans were German soldiers dispatched to retrieve them. Not willing to face the consequences, the desperate soul chose suicide.

At 11:15 am, the scouts signaled, “Halt!” and slipped to their knees. Before them a broad clearing, perhaps 200 yards deep, had been hacked from the forest and bristled with a sea of ice-encrusted barbed wire—double apron and concertina—six to 10 rows deep. Further scrutiny revealed that deep ditches had been excavated to prevent armored attacks while other natural ravines were piled high with coils of concertina wire. At the far end of this daunting obstacle wisps of smoke snaked above the treetops, indicating that the position was indeed occupied.

It was a frightening sight for the scouts, but had they known what else lay in store they may have blanched white. Hidden beneath the snow and interspersed amid the wire were hundreds of sinister land mines—the nasty Schu mines designed to cripple any who disturbed them and the dreaded S mines, dubbed Bouncing Betties by the GIs because when they were tripped they sprang to waist level before exploding, flinging hundreds of lethal ball bearings in every direction. Also lying beneath the snow was a web of tripwires capable of triggering several mines simultaneously.

Even worse, 24 mutually supporting pillboxes and bunkers glowered from the distant treeline, each constructed of steel-reinforced concrete six to eight feet thick. Some were no more than 20 to 30 yards apart and so well camouflaged that they were undetectable. Zigzagging communications trenches linked one to the next, while additional trenches provided shelter for supporting mortar and machine-gun crews. Four pillboxes and six bunkers were clustered around the crossroads itself, supplemented by the forester’s lodge and customs house, both formidable fortresses. Adding depth to the defenses, the Germans possessed four batteries of artillery, all preregistered, to join the mortars and machine guns to create the perfect killing field. It was German defensive doctrine at its best.

A Costly American Attack

Packs were dropped in anticipation of imminent action. The American officers still believed that the enemy remained ignorant of the division’s presence and ordered an immediate attack. Higgins’ 2nd Battalion, which was first to arrive, went straight in while McKinley’s 1st Battalion, still struggling through dense forest, pressed forward on the left. Lt. Col. William F. Kernan’s 3rd Battalion hunkered in the woods as regimental reserve.

By then visibility had increased to 500 yards, and with the fog’s dissipation so vanished the chance of a veiled approach. No sooner had the leading squads emerged from the forest than the far treeline erupted with the chilling rip of MG-42 machine guns. The battle of Wahlerscheid Crossroads had begun. Bullets lacerated the ranks at 1,200 rounds per minute. Within moments German mortar shells commenced their deadly promenade, erupting among the prostrate soldiers with uncanny accuracy. In one 12-man squad of Company G, eight were killed outright while four bullets shattered another’s arm. The enemy had been waiting all along.

The Americans realized that the element of surprise had been lost, and the supporting artillery went into action. Six thousand yards to the rear, the big American guns belched fire and steel, but lacking proper registration did little appreciable harm. Even so, shells fell in such quantity that the enemy fire tapered off momentarily, giving heart to the assault companies, which again surged forward.

In the 2nd Battalion sector, Captain Homer G. Ross’s Company E attacked on the left while Captain James A. Force’s Company G advanced on the right, but both were stopped cold by impenetrable masses of barbed wire. Desperate to break through, soldiers thrust Bangalore torpedoes beneath the obstructions, but the fuses were damp and would not ignite. By then the enemy had recovered from the shocking bombardment, and again bullets clattered amid the wire.

One platoon of Company E wormed through five aprons of barbed wire before becoming pinned down by concentrated mortar and machine-gun fire. Further movement set off antipersonnel mines or drew the wrath of additional weapons. Casualties soared. Unable to move forward or back, the survivors did not escape until dark.

Meanwhile, another E Company platoon bellied onto a slight elevation which offered good observation of the enemy line. Acknowledging its value, Captain Ross grabbed two radio men, scrambled to its crest, and began relaying coordinates of identified pillboxes to the supporting artillery until a deluge of high explosives rendered their position untenable.

While Company E was being slaughtered in the open, Captain Force’s Company G tried to take advantage of scrubby, undulating terrain on the right, but tangles of barbed wire barred the way. In some ditches the concertina was piled six feet high. Again Bangalores were requested but failed to ignite. By then automatic weapons fire was sweeping the front with devastating effect, while mortar rounds crashed with regularity. Although the attack had hardly begun, it was evident that such head-on tactics were suicidal.

Throwing in the Reserves

Noting that Higgins’ men were helplessly impaled on the wire, Colonel Hirschfelder ordered his reserves into action. At 3 pm, Lt. Col. Kernan’s 3rd Battalion swung through the woods to 2nd Battalion’s right, intending to flank the troublesome pillboxes. Captain Jack A. Garvey’s Company K probed forward on the battalion’s left while Captain Bruce C. Cagle’s Company L pushed through on the right with Captain William J. Ray’s Company I trailing as reserve.

Using the forest as cover, the leading elements got to within 75 yards of the enemy’s line before another series of undetected pillboxes took them under fire. Immediately, the two leading scouts were down. More gunfire raked the line. Within minutes mortar shells came plunging down, followed by heavier artillery that tore through the treetops at an alarming rate. By evening, Kernan’s flanking maneuver had ground to a halt. Ordered to hold in place, his men pulled shovels from scabbards to hack at the frozen soil.

As daylight waned a mournful wail wafted from 50 yards in front of Company K. Heeding the plea, a medic worked his way forward only to be dropped by a sniper, even though his uniform was clearly marked with giant red crosses on his chest, back, and helmet. A second medic homed in on the wretched sobbing, but again a solitary shot rang out, killing him. Eventually the whimpering tapered and then ceased altogether, leaving his ashen-faced comrades to resume their solemn excavations.

Clearing Lanes in the Minefield

An hour and a half after Higgins’ battalion had commenced its noon assault, Lt. Col. McKinley’s 1st Battalion had finally broken through the forest on the regiment’s left, 600 yards southwest of the junction. An interdicting road separated them from a vast wasteland of snow-capped underbrush extending 500 yards, and beyond that lay multiple tiers of enemy defenses. Seeing no alternative to a frontal attack, McKinley ordered his battalion forward.

Captain Louis C. Ernst’s Company C pushed across the road under galling fire. Immediately, one man set off a mine, followed by another. In short order 10 men were down, victims of crippling Schu mines or Bouncing Betties. Minesweepers from the Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon were summoned. Covered by riflemen, the sweepers painstakingly cleared a lane 400 yards beyond the road. The infantry filtered forward in preparation for the main assault but were checked by intense mortar and machine-gun fire. Forward observers called for supporting artillery, but the shells fell far and wide.

By 3:30 pm lanes had been cleared well into no-man’s land, but twilight was fast approaching and further operations were halted. Just before dark a fierce mortar barrage ravaged the battalion’s right flank, followed by a halfhearted counterattack. For 45 minutes grenades thumped and rifles barked before the line was stabilized and order restored.

As darkness approached, Colonel Hirschfelder realized he was facing a catastrophe. As a precaution, he stripped Company I from Kernan’s command and pulled it back behind 2nd Battalion to serve as regimental reserve while the other assault units dug in for the night. Some were barely 100 yards from the menacing pillboxes.

Dugan’s Patrol

Unknown to the American command structure, there was one remarkable achievement that day. It was during the chaotic battles on the 2nd Battalion front that Technical Sergeant Dugan, leading nine men of 3rd Platoon, Company G, had managed to wriggle beneath 40 yards of barbed wire to gain the enemy’s trench system, losing one man killed during their approach.

Once within enemy lines, Dugan monitored a pair of pillboxes that sat at either end of the zigzagging trench and continued to flay the plain with intermittent machine-gun fire. As he considered his options, the German rear guard suddenly noticed that several more GIs were slithering through the wire. When a string of tracers flitted over the infiltrators’ heads, Dugan called for covering fire until all four tumbled, exhausted, into the trench. Led by Sergeants James Dunn and Adam Rivera of 1st Platoon, these men had been dispatched to support Dugan’s forlorn hope. Armed with wire cutters, they had managed to clear a four-foot-wide swath all the way to the enemy line, having lost two men wounded while doing so.

Now 13 GIs crowded the narrow trench. No sooner had Dugan commenced explaining the situation to Dunn and Rivera than a flurry of bullets cracked past their faces. Startled, GIs spun just in time to repel a group of Germans that had sallied from the pillbox to their right. In the confusion Dugan’s men dragged a captive into their trench just as contact was broken. In faltering English, the stuttering German assured Dugan that if released he could convince the others to surrender. After weighing the odds, Dugan reluctantly set him free.

The squad formed an all-around defense and waited. Time dragged. Suddenly, movement in the connecting trench indicated that perhaps the gambit would produce dividends. Just as Dugan cautioned his men to prepare to accept prisoners, the muzzle of a machine gun poked around the trench corner, followed by a coal scuttle helmet. Dugan took aim and fired. The gunner dropped. Hollering a warning, Dugan clambered up the parapet and commenced triggering round after round into the body-choked trench, killing one more German. The enemy scrambled for cover.

Within moments a second German patrol joined the action from the nearby woods, followed by another and yet another. Assailed from three sides, Dugan’s squad fought like demons. When the BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) gunner fell, Pfc. Bento Roposa retrieved the weapon and released one rattling burst after another until a bullet punctured his stomach. Enraged, Roposa regripped his weapon and continued his furious fusillade. Then a grenade plopped in and exploded. Fragments ripped through Roposa’s arm, but the scrappy soldier continued to lay down accurate fire until loss of blood caused him to pass out, but not before he dropped one more German who was creeping toward his position.

After five hours of continuous action, Dugan’s beleaguered command finally withdrew under cover of darkness, dragging two wounded comrades with them; two dead remained behind. Except for Dugan’s patrol, no others had gotten even close to the enemy’s works.

Orders to Assault Wahlerscheid Crossroads

Meanwhile, back at Hirschfelder’s command post staff officers studied maps and patrol reports to no avail. The tangles of barbed wire remained a vexing obstacle. Heavy concentrations of mortar and artillery fire combined with interlocking machine-gun fire thwarted every attempt to break through, and Kernan’s flanking maneuver had stalled. Although American artillery had cleared some of the foliage that masked several pillboxes, many others remained undetectable. It was decided to resume the assault against the German positions in the morning at 8:30.

Throughout the night incoming artillery ravaged the forest canopy. Explosions cracked like thunderclaps as fireballs blossomed high overhead, flinging torrents of shrapnel on the hapless, cowering men. Splintered branches followed every burst, and sometimes entire trees snapped and crashed to the forest floor. Although cooks had prepared a hot meal, it could not be served due to the heavy shelling.

As the evening progressed, the temperature plunged. Curled in shallow foxholes, soldiers already drenched from the strenuous march through the dripping forest draped sodden blankets over shivering shoulders as they attempted fitful sleep. Those of the assault companies, having dropped packs prior to their attack, lacked blankets and suffered accordingly. By morning everyone’s clothing had frozen stiff.

At first light on December 14, the American artillery resumed its fierce cannonade with some batteries focused on destroying known pillboxes while others concentrated on breaking up the wire entanglements to aid the infantry. After 15 minutes, the guns shifted to harass the enemy’s lines of communication while the infantry prepared for action.

Upon receiving his attack orders, Lt. Col. McKinley decided elements of Captain John B. Cornwell’s Company B and a detail from the Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon would continue to cut wire and remove mines to create lanes of attack. Once this was accomplished, the balance of his battalion would push through in column to assault the pillboxes guarding the crossroads.

An experienced commander, McKinley regarded his assignment with reservations. He realized that even if successful his battalion would be subject to counterattacks from the east, north, and west. Nonetheless, he ordered his companies forward.

American Attacks Repulsed

Cornwell’s men pushed off on schedule. In rapid succession, eight men were killed or wounded while gapping the wire, but by noon sufficient penetration had been made to allow the final assault to proceed. Covering fire hammered pillboxes while a heavy smokescreen masked the approach of 1st Lt. Robert Kauth’s Company A as it passed through Cornwell’s line. Kauth’s men advanced 150 yards through murderous mortar and machine-gun fire before stumbling on another belt of concertina. Again forward observers called for covering fire as wire-gapping teams wriggled beneath a blizzard of German steel. Realizing little headway was being made against such savage resistance, McKinley recalled his troops at mid-afternoon.

While McKinley’s men wallowed in the frozen hell on the left, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions resumed their attacks on the right. Directing the battle from a ditch a mere 500 yards from the nearest pillbox, Lt. Col. Higgins already had problems. Earlier a number of short rounds of the preliminary barrage had smashed a platoon of Company E, so disrupting organization that Captain Ross’s entire command was unable to participate in the forthcoming assault. As a stopgap measure Higgins wrenched a platoon from 1st Lt. Fred J. Arnold’s Company F and shoved it between two platoons of Company G, which was slated to make the 2nd Battalion’s main effort. The balance of Company F would follow as battalion reserve.

Company G, now under the command of 1st Lt. John M. Jacques, jumped off in the face of withering fire, pushed up a shallow, tree-studded draw in an effort to reach the nearest pillboxes, but soon encountered another rat’s nest of prickly wire. Demolition men crept forward, this time dragging dry Bangalores, and blew a gap wide enough to accommodate the leading squad. Bodies stacked one upon the other as machine guns dropped the first four men to enter, while a fifth was killed after tripping a mine.

Disheartened, the others sought refuge in the shallow defile while frantic pleas went out for supporting artillery. Shortly after 1 pm, explosions rippled all across the front, but terrain variables hindered proper registration. After an hour of futile readjustments, the battalion was ordered to withdraw. By then the enemy’s preregistered mortars and artillery were wreaking havoc in a draw now teeming with wicked tree bursts.

Simultaneous to Higgins’ attack, Lt. Col. Kernan’s 3rd Battalion resumed operations on the regiment’s right but was also stopped by a combination of massed wire, mines, and intense gunfire emanating from several mutually supporting pillboxes. Still hoping to outflank the German defenses, Kernan decided to send one company looping through the zone of the neighboring 395th Infantry, which was making a supporting attack on the division’s right.

Using Company K as a base of fire, Bruce Cagle’s Company L set out on its circuitous route with three bazooka teams attached. While passing through a sparsely forested region they chanced upon a slight depression that ran almost under the nose of the easternmost pillbox. Believing that this indentation would provide a degree of security, Cagle launched his attack.

By ones and twos, soldiers sprinted toward the dubious shelter of the swale. The enemy opened fire. Shrapnel toppled six men while machine guns accounted for 14 others. Several intrepid GIs managed to press beyond the embankment but were soon driven back. As the volume of incoming fire intensified, the situation seemed doubtful. By 1 pm, Kernan, too, felt compelled to call off his attack.

Having been beaten at every turn, regimental command ordered a general withdrawal at 2 pm. At twilight the 2nd Battalion fell back a full 500 yards to take positions in the woods behind the battalion command post still hunkered in its muddy trough at the fringe of the clearing, while 50 unfortunates of Company E remained exposed in the glacial plain to man forward outposts. Kernan’s 3rd Battalion deployed behind 2nd Battalion to resume its role as regimental reserve. Waiting until dark, McKinley’s 1st Battalion broke contact with the Germans and withdrew under the protection of a covering barrage to reclaim its original position southwest of the road junction.

Again sequestered in the forest, soldiers sought refuge from the inevitable tree bursts, while others, the first of many to be afflicted with respiratory ailments or frozen feet, began the painful trek to the rear. By then, the divisional engineers had finally cleared the solitary supply route of obstacles and mines, permitting the arrival of ammunition, blankets, and a welcome hot meal. In the meantime, a pair of self-propelled 155mm guns from Battery C, 987th Field Artillery maneuvered to within 3,000 yards of the junction and began pasting pillboxes with armor-piercing shells. Although a total of 176 rounds were expended, it was later discovered that the massive structures suffered only superficial damage.

An Opportunity to Uproot the Pillbox Defenders

Meanwhile, battalion and regimental staffs struggled to find a solution to their dilemma. Earlier, General Robertson had admonished Colonel Hirschfelder for not conducting more thorough reconnaissance before resuming his attacks. In light of this, patrols were dispatched to probe for fissures in the seemingly impregnable defenses, while arrangements were made for a tactical airstrike in the morning. Noting that Hirschfelder’s exhausted regiment was on the brink of collapse, Robertson ordered Colonel Francis H. Boos to ready his 38th Regiment to take up the attack. After two days of brutal assaults, the division had not gained a single foot.

By daybreak on December 15, the situation remained stagnant. The scheduled airstrike was cancelled due to heavy fog, resulting in a temporary suspension of offensive operations. In lieu of the aerial bombardment, 11 battalions of artillery unleashed hell on earth, ripping up wire and collapsing earthen trenches while other shells battered the massive bunkers and concrete pillboxes.

At about 10 am, something totally unexpected occurred. Although German small arms fire continued to harry the front, all incoming artillery ceased. This was a most perplexing, albeit welcome, turn of events. What was not known was that the 277th Volksgrenadier Division was being relieved by the poorly trained 326th Volksgrenadier Division so that the former could participate in Hitler’s upcoming winter offensive in the Ardennes Forest, which became known as the Battle of the Bulge. As the various Wehrmacht units exchanged positions, their heavy guns fell silent.

There was one more glimmer of hope that day. While inspecting Company G, Lt. Col. Higgins was finally informed of the singular penetration made by Sergeant Dugan’s patrol. This noteworthy event had not been relayed up the chain of command due to the confusion experienced when the company commander, Captain Force, had been wounded and evacuated. Sensing an opportunity, Higgins decided to capitalize on this unexpected boon. If the German artillery and mortars remained silent, Higgins planned on dispatching a reinforced patrol through the gap under cover of darkness to report the enemy’s disposition via sound-powered phone. If feasible, his battalion would then filter forward to surprise and eliminate the stubborn pillbox line while Kernan’s 3rd Battalion pushed on to cut the Wahlerscheid-Dreiborn highway before assaulting the actual crossroads.

American artillery would continue to saturate the entire area to restrict enemy activity while these maneuvers proceeded. Believing his plan had a reasonable chance of success, Higgins presented it to Colonel Hirschfelder, who in turn took it to General Robertson, who gave his consent. It was a long shot but a gamble worth taking.

“We Have Surrounded One of the Pillboxes. No Opposition.”

At 8 pm, Higgins summoned Sergeant Dunn to his command post, believing that since Dunn had been a member of the original foray he would be able to retrace his route to the enemy trenches. However, by then Dunn was in such poor physical condition that it was decided to send Sergeant Rivera, another original patrol member, in his stead.

Flickering explosions illuminated the front as Rivera’s 11-man team slithered into no-man’s-land. Colonel Higgins waited with bated breath as time ticked by … 20 minutes … then 30. Still no word. Finally, 45 minutes after Rivera’s departure a soft whistle pulsed through the phone line. Anxious, Higgins monitored the report and it was not good. The patrol, confused by the maze of barbed wire, was inexorably lost in the darkness. The men could not find the route. Frustrated, Higgins ordered the entire patrol to return by following its phone line. Meanwhile, Sergeant Dunn was recalled and asked if he felt up to the challenge. Although exhausted, Dunn agreed. By then Rivera’s patrol was bellying into the American lines.

Guiding on Rivera’s phone line, Dunn’s party departed at 9 pm. Within 30 minutes Dunn was relaying good news. They were safely in the enemy’s trench and were preparing to investigate the first pillbox. Not a shot had been fired. Higgins was practically giddy at the prospect of success. Fifteen minutes later Dunn was again blowing into the mouthpiece: “The Germans don’t seem to be alert. We have surrounded one of the pillboxes. No opposition.” Higgins was ecstatic.

Immediately, Higgins began feeding his battalion through the gap. Traveling single file, 1st Lt. Fred J. Arnold’s Company F slipped forward following a strip of white engineering tape strung by a platoon of Company G, which was posted along the route to act as guides. Upon entering the trench system, Arnold’s men deployed to the left of the breach. Captain Ross’s depleted Company E came next, accompanied by Lt. Col. Higgins, and built up along a firebreak to the right. The balance of Company G assumed the role of battalion reserve. By midnight the 2nd Battalion had achieved a 300-yard bridgehead without the enemy’s knowledge.

While Sergeant Dunn’s men kept vigil on the first pillbox, Higgins joined Company F, now hunkered in the trench before the second pillbox to Dunn’s left. Gambling on the enemy’s apparent ignorance of the Americans’ presence, Higgins stealthily clambered onto the roof of the second pillbox to direct Arnold’s men in surrounding it. Two more platoons eased farther down the line to cover the next two pillboxes. With his battalion poised for action, Higgins’ radio crackled: “Bring up the 3rd Battalion.”

By 1 am, Kernan’s battalion was slipping forward. Upon reaching Higgins’ position, the two commanders decided that 2nd Battalion would clear out the pillboxes in the immediate area while Kernan would pass through Company E to push 400 yards deeper, utilizing the firebreak that angled northwest behind the pillbox line to cut the Wahlerscheid-Dreiborn road. From there he would march west to reduce the fortifications guarding the actual junction.

“Kamerad! Wir Nicht Schiesen!”

No sooner had Kernan’s battalion cleared Company E’s perimeter than Higgins gave the command to attack. A fusillade of .30-caliber bullets powdered the concrete framing the narrow firing slits of the first pillbox in Company F’s area. Other rounds hammered the iron aperture guarding the rear entrance as an assault team bolted forward to place a beehive charge against the steel door. Before the ringing blast faded, GIs rushed forward to fling grenades through the smoldering entrance or blast the interior with bazooka rockets.

“Kamerad! Wir nicht schiesen!” the Americans shouted, hoping to coax any survivors into capitulation, “Surrender! We won’t shoot!” However, after three days of suffering in the freezing, bullet-swept plain, the men of the 9th Infantry were in no mood for clemency. Any Germans who did not emerge with their hands clasped over their heads were killed outright. In this manner the platoons of Company F leapfrogged from one pillbox to the next, eliminating each in turn.

By daylight two previously unidentified pillboxes loomed 500 yards to the battalion’s right. Immediately, a platoon of Company F was dispatched to knock them out. While advancing through scrub and pines the platoon was counterattacked by 17 Germans. In the ensuing gunfight the Americans suffered one wounded, while four Germans were killed, four wounded, and four more taken prisoner. The remaining five escaped unharmed. By 9:30 am, the 2nd Battalion had neutralized seven pillboxes. A half hour later its entire sector was in American hands.

The Rumblings of the Ardennes Offensive

While Higgins’ men battled for control of the first tier of pillboxes, Kernan’s battalion navigated the dimly lit firebreak, intent on gaining the east-west Dreiborn road. En route, the leading squad startled several sentries guarding a concealed bunker, initiating a brief but chaotic firefight before the outpost was overwhelmed and the infiltration resumed. Shortly afterward, the point element stepped onto the highway. Wahlerscheid junction now lay but a short hike away.

In the darkness, Captain Garvey’s Company K slipped past the first five pillboxes encountered as well as the fortified customs house to deploy before yet another pillbox situated at the triangular crossroads. At the same time, 1st Lt. Melvin S. Goldstein’s Company L closed in on two of the five bypassed pillboxes while Captain Ray’s Company I surrounded the remaining three to the east.

As the men readied for the assault, a deep-throated rumbling resonated from the eastern horizon, now shimmering with splashes of pink and red. It was precisely 5:30 am, December 16, 1944. Although they did not know it, they were witnessing the opening blows of Hitler’s desperate winter offensive—the Battle of the Bulge. The men of the 2nd Infantry Division hunkered in the frozen landscape before Wahlerscheid junction believed that the violent exhibition was merely a reaction to the Roer Dams attack and had no bearing on the dire task presently before them.

Clearing Pillboxes

At Wahlerscheid the disorganized soldiers of the newly arrived 326th Volksgrenadier Division remained blissfully ignorant of the storm that was about to engulf them. Many were fast asleep in their bunkers believing that the Americans were still stalled before the barbed wire, hundreds of yards to their south.

On command, the Americans sprang into action. Sheer pandemonium supplanted false tranquility as suppressive fire raked pillbox embrasures or thudded savagely into the surrounding entrenchments. Beehive charges ripped open the fortifications’ rear doors. Grenades were tossed in. Kernan’s battle-weary soldiers possessed the same foul temperament as those of Higgins’ 2nd Battalion, and any Germans who refused to surrender were quickly eliminated.

Captain Garvey’s men jumped the pillbox before them, and by 6:45 am had the situation under control. Meanwhile, Goldstein’s Company L successfully assaulted its assigned pillboxes, then moved on to the nearby customs house where 2nd and 3rd Platoons formed a protective arc as 1st Platoon rushed the building at the break of dawn. The startled defenders, many still groggy with sleep, were taken completely by surprise, and within minutes 77 befuddled Wehrmacht soldiers filed from the building with fingers interlaced above field caps. Not one American was injured.

Success With High Casualties

While Goldstein’s men gathered their prisoners, Company K continued westward to a secondary road junction, which was secured by 8 am. Meanwhile, Company I had seized the three easternmost of the five bypassed pillboxes, then crossed the highway to assault two more, farther north. By 9:30 am, the 3rd Battalion had secured the crossroads.

The enemy line was clearly crumbling. Upon receiving word of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions’ breakthrough, Lt. Col. McKinley’s 1st Battalion was ordered forward at first light. Company B, now led by 1st Lt. John L. Milesnick, moved out over ground that had previously been fiercely contested. Much to their delight, incoming fire was surprisingly light. Creeping forward, they managed to cut additional lanes through the wire at a cost of only four casualties, one from small arms fire and the others from mines. Once inside the entrenchments, they blew up one pillbox, which paved the way to the Wahlerscheid junction. The enemy’s ability to resist had been greatly reduced by the confusion following the troop exchange of the previous day.

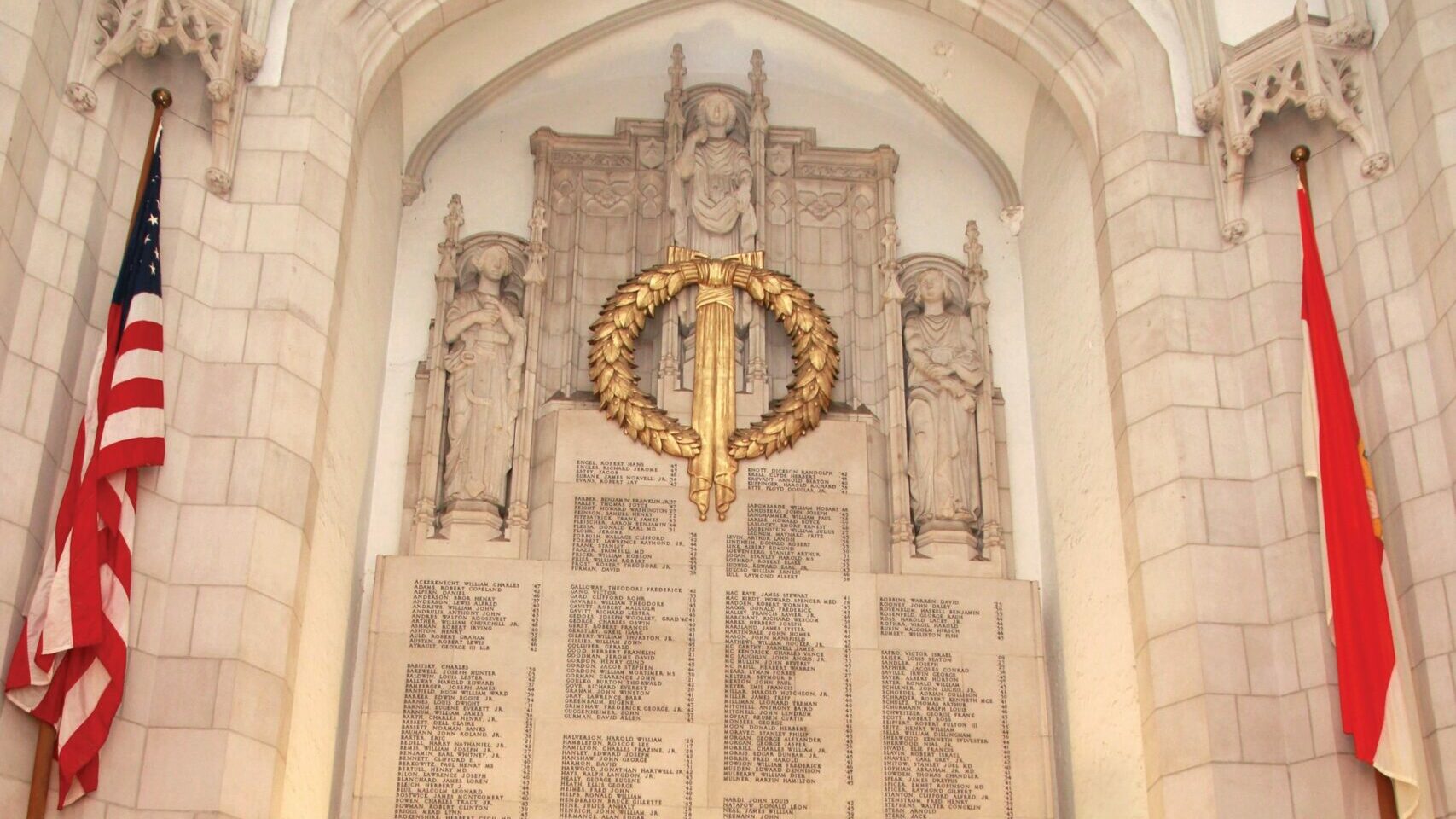

By 10:15 am, McKinley’s battalion had linked with the 3rd Battalion at Wahlerscheid, where the entire regiment dug in. By then, two battalions of the 38th Infantry were already trudging through the forests flanking the Dreiborn road to continue the drive toward the Roer River dams. After four days of suffering through shot, shell, and inclement weather, the Manchu Regiment had taken one of the most heavily defended sectors of the Siegfried Line, netting 24 pillboxes, bunkers, and fortified positions. But the cost had been high. All three battalions had been reduced to half strength, with battle- and weather-related casualties more or less equally divided.

Withdrawing to Fight in the Bulge

At dusk the battalions surrounding Wahlerscheid received varied amounts of artillery and mortar fire while repelling several spirited counterattacks, but the Manchus refused to yield. However, the battle of Wahlerscheid Crossroads was to be a pyrrhic victory.

Alarming reports flashed from the south. “Heavy enemy bombardment pounding the entire Ardennes sector; numerous penetrations by strong infantry and armored forces all across the front.” Chaos and mayhem gripped the soldiers manning the thinly held “Ghost Front.” The Battle of the Bulge was upon them.

General Gerow was gravely concerned over these unsettling developments. Elements of Robertson’s 2nd Division were seven miles deep in enemy territory with only one poor road as their main supply route. If this road were cut, Robertson’s nagging premonition at the outset of the operation could prove prophetic. Two entire regiments could be isolated and destroyed. Fearing the worst, Gerow requested an immediate withdrawal of his attacking forces. Initially, Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, First Army commander, refused, believing the enemy was merely launching spoiling attacks in response to the Roer River dams offensive, but in time he too realized the gravity of the situation and grudgingly gave his consent.

In the dimming light of December 17, the 2nd Infantry Division disengaged and commenced a piecemeal withdrawal under fire across a crumbling front to assume defensive positions at its jump-off point of Rocherath, Belgium. In the following days, these men would fight one of the pivotal actions of World War II as they denied General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army access to three of its five assigned routes toward the port city of Antwerp, Belgium.

In the dreary twilight of December 17, 1944, the soldiers of the 2nd Infantry Division were in a foul mood as they trudged past the battered fortifications of Wahlerscheid. Being forced to relinquish their hard-won gains without a fight was a bitter pill to swallow, and afterward the men who wore the Indian Head shoulder patch would refer to the battle-scarred junction as “Heartbreak Crossroads.”

Great read sir!