By Alexander Zakrzewski

During the mid-14th century, a new theater of the crusades erupted, this time on the doorstep of Christian Europe. The Ottoman Turks, once just one of many pastoral Turkic tribes wandering the Anatolian steppe, had united into a powerful and sophisticated military state. Under the leadership of a series of brilliant sultans, they had expanded steadily westward, mostly at the expense of the aging and decaying Byzantine Empire. After conquering most of Anatolia, they crossed the Hellespont and established themselves in the Balkans, even moving their capital to the city of Adrianople, which they renamed Edirne.

The Ottomans were fortuitous to have arrived in Europe at a time when the entire continent seemed to be coming apart at the seams: the Byzantine Empire was barely clinging to life; England and France were locked in a ruinous Hundred Years’ War; the Italian city states were consumed by greed and mutual hatred; the Papacy was divided by schism and rival popes; and even the once powerful Balkan kingdoms of Serbia and Bulgaria were beset by dynastic problems. Worse still, Genoese galleys in 1347 had unwittingly carried the Black Plague to every harbor on the Continent, devastating the population and economy.

Not surprisingly, Christian Europe’s response to the new Ottoman threat was slow, half-hearted, and uncoordinated. In 1396, after subjugating Bulgaria and reducing Serbia to a vassal, Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I began to threaten Hungary. The Hungarian king and Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund of Luxembourg, appealed to Pope Boniface XI for help and a crusade was called. Nobles from Western Europe travelled to Hungary to help repel the Ottomans.

The Nicopolis Crusade, as the campaign is remembered, was a disaster. The Catholic nobles behaved like a drunken mob on the march south through the Danube corridor, massacring Turkish prisoners, abusing the local Orthodox peasantry, and refusing to follow orders. When they met Bayezid in battle, they repeated the mistakes of Crecy and Poitiers and launched foolhardy cavalry charges that succeeded only in wearing out their own horses. After a fierce fight, Sigismund and what was left of his army were forced to flee back to Hungary, leaving thousands of prisoners behind to be executed in revenge for their earlier atrocities.

Much to the relief of Christian Europe, just six years later Bayezid was himself defeated and captured by the Mongol conqueror Tamerlane at the Battle of Ankara. The loss of the sultan plunged the Ottoman Empire into a decade-long civil war from which, for a period of time, it looked as if it would never recover. Bayezid’s youngest son emerged the victor as Sultan Mehmed I. He restored order and rebuilt the military. By the time he died in 1421, his son Murad II was in good position to once again resume hostilities against Christian Europe.

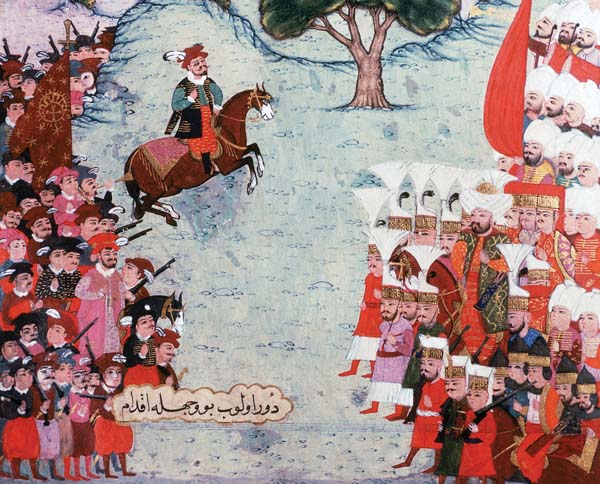

Stern, aggressive, and clear in his sense of duty and purpose, Murad was exactly the type of ruler the empire needed after years of disorder. He was deeply religious and styled himself the Ghazi Sultan, a champion of Islam sworn to spread the faith and protect the faithful. He had no patience for dispute or dissent, even from his own household. When his headstrong son, the future Mehmed II, refused to listen to his tutors, he ordered the boy beaten into submission. On another occasion, when a renowned and respected imam scolded him for drinking alcohol, ironically his one major indulgence, he had him thrown into prison.

Murad began his reign by laying siege to Constantinople. He failed to take the city but forced Byzantine Emperor John VIII to agree to a humiliating peace that basically ceded away all the territory outside the city walls. Murad then began a series of campaigns to reassert the empire’s control over the Balkans. First, he subdued the Venetians, the dominant power in the eastern Mediterranean, by ravaging their possessions in Greece and Albania and taking the rich city of Thessaloniki. Next, he marched north, reclaiming lost territory and forcing the rebellious Serbian Despot George Brankovic to seek sanctuary in Hungary.

It was on the Hungarian frontier that Murad’s forces encountered one of the most brilliant soldiers of the age. John Hunyadi’s origins are mysterious and widely contested. He was of relatively lowborn stock and was believed to have fabricated his own family crest and noble lineage. As a young man, he entered the service of King Sigismund, with whom he travelled across Central Europe and Italy. There he mastered the prevailing tactics and strategies of the time and soon became one of Sigismund’s most valuable commanders.

Hunyadi was posted to Hungary’s restless southern border at just about the same time that hostilities were once again arising with the advancing Ottomans. There he cleverly adapted the tactics he had learned abroad to the narrow valleys and rugged foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. In 1441 he was made voivode of Transylvania, and in the following few years he won a series of stunning victories that made him famous throughout Europe as the “White Knight of Transylvania.” The nickname spoke to both his celebrated reputation as a defender of Christendom and the shining suit of Milanese plate armor he wore into battle.

In 1443 Hunyadi achieved one of his greatest successes in a whirlwind offensive known as the Long Campaign. While Murad was distracted with revolts in Greece and Albania, Hunyadi invaded Serbia, then crossed the Balkan Mountains in the dead of winter and overran most of Bulgaria. In the process he defeated three Ottoman armies sent to stop him. He might have pressed even farther had he not been hampered by the weather and a lack of supplies. Regardless, that spring he returned to Buda in triumph, and a shocked Murad sent peace envoys to offer very generous terms.

Hunyadi’s forces were exhausted and he was equally as eager to come to terms; however, he had a powerful patron with ambitions of his own. In his capacity as Hungarian voivode, Hunyadi served 19-year-old King Ladislas who held the dual crowns of Poland and Hungary. As king of Hungary, Ladislas was responsible for securing Hungary’s southern frontier against the Ottomans. As far as Hunyadi was concerned, this objective had been achieved. But Ladislas, being young, glory hungry, and imbued from birth with the ideals of Christian chivalry, believed the Ottomans were on the verge of being expelled from Europe altogether.

Ladislas was himself also under pressure from Pope Eugene IV—more specifically, his papal envoy Cardinal Giuliano Cesarini. The cardinal had supported Ladislas’s election to the Hungarian throne. In so doing, he became a close confidant of the young monarch. He shared Ladislas’s belief that the Ottomans were on their last legs. Cesarini believed that freeing the Orthodox peoples of the Balkans would bring the two churches closer together and lay the groundwork for a reunification of the two branches of Christianity. While peace negotiations with the Ottomans were under way in April 1444, Ladislas took a solemn oath to lead a crusade by year’s end.

Murad and Ladislas agreed to a 10-year truce in June that Ladislas clearly had no intention of keeping. A strange series of events then followed. The sultan, fully planning to honor the agreement, withdrew from Europe with his army to lead a punitive campaign against one of his rebellious Anatolian vassals. Having secured both his Asian and European frontiers, he then shocked the world by announcing that he was exhausted by the strain of constant campaigning and was abdicating the throne in favor of 12-year-old Mehmed.

In Christian Europe, news of Murad’s abdication caused a flurry of excitement, particularly in Hungary where both Cesarini and Ladislas believed that with the Ottoman Army far away in Anatolia, and an inexperienced child on the throne, a golden opportunity had presented itself. Cesarini immediately declared the truce to be void on the basis that an agreement with an infidel was not worth the paper it was printed on. At a diet in Buda, Ladislas boldly declared that he would drive the Ottomans out of Europe.

An audacious plan was drawn up by which Ladislas, with Hunyadi as his commander in chief, would lead a crusader army south along the route of the Danube River into Ottoman-controlled Bulgaria, proceeding as far as the Black Sea coast. When the crusader army arrived at the coast it would rendezvous with a Venetian fleet that would resupply it for the final leg of its march to Edirne. All the while, the Venetians would blockade the straits between Europe and Asia, trapping Murad and his army in Anatolia and ensuring that the crusaders would be relatively unopposed as they rampaged across the Balkans. It was also hoped that the various peoples of the Balkans would take the opportunity to rise up against their Ottoman overlords, further clearing the way for the crusaders.

To accomplish this ambitious undertaking, Ladislas had at his disposal an army of 16,000 men. It was a multinational force made up of Hungarians, Poles, and Papal troops. Within each group were smaller ethnic contingents from across the diverse peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. For example, the Polish contingent included Lithuanians and Ruthenians. The Hungarian and Transylvanian troops included Croatians, Szeklers, and Saxons. Prince Vlad II of Wallachia, the father of the future Vlad the Impaler, contributed 4,000 horsemen led by his son Mircea II. These wild riders of the Carpathian frontier were among the most exotic of the crusader forces, easily distinguished by their short round beards, tall fur caps, and a lack of armor, which they considered unmanly.

Despite his generous contribution, Vlad voiced grave concerns over the coming campaign. He warned Ladislas that the sultan’s hunting party alone would outnumber the crusaders. He was not the only one to have doubts. Hunyadi also desperately wanted to abide by the hard-won peace treaty and did everything he could to convince Ladislas to change his plans. Brankovic, who Hunyadi had recently restored to power, believed that diplomacy was the best way to secure his kingdom’s survival and not only refused to participate, but actively sought to dissuade other Balkan rulers from doing so.

These protestations had no influence on Ladislas, who refused to break his crusader vow. On September 18, 1444, he led his army across the Danube River into Ottoman territory. At first things went well. The crusaders made slow but steady progress, taking Ottoman strongholds along the way and winning the support of the local Christians. The news of the invasion caused a wave of panic in Edirne that led to riots and the flight of much of the population.

It was not until the crusaders reached Nicopolis that they encountered their first real resistance. The town fell easily enough, but the Ottoman garrison in the nearby fortress refused to surrender and fought doggedly. The crusaders decided to bypass the fortress, but much to their vexation, the farther they advanced, the fiercer the resistance seemed to become. Ladislas also grew frustrated by how his troops seemed to show more interest in booty and plunder than in fulfilling their crusader vows. He and the other commanders consoled themselves with the knowledge that at least Murad and his army were far away in Anatolia, safely contained by the Venetian fleet.

It soon became apparent that the crusaders had not banked on two crucial factors. The first was the surprising wisdom and self-awareness of the young Sultan Mehmed. Upon receiving news of the crusade, he immediately sent his father a stern letter demanding that he return to the throne. “If you are the Sultan, come and lead the armies,” he wrote. “If I am the Sultan, I order you to come and lead the armies.” Murad did as his son asked and returned to power, bringing with him his years of experience and the loyal respect of the Ottoman army and people.

The other factor was the greed of the Venetians’ hated rivals, the Genoese. For the exorbitant price of a ducat a head they agreed to transport Murad and his army across the straits. In mid-October, while the crusaders were still busy battling their way along the Danube, Murad crossed into Europe right under the nose of the Venetians. He immediately began marching north to confront the invaders, rallying together as many more men as he could along the way. By the end of the month, his force had grown to 60,000 men. By November 8, less than three weeks since crossing the straits, he was only a day’s march from the exhausted crusaders who had only just reached the city of Varna on the Black Sea.

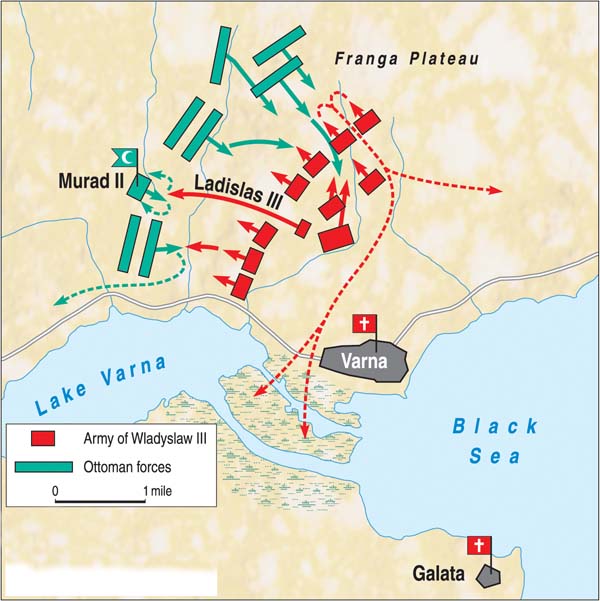

On November 9, 1444, scouts under the command of Michael Szilagyi, Hunyadi’s brother-in-law and one of his most trusted captains, spotted the Ottoman army advancing in full battle array to a plain five miles west of Varna where they set up camp. Ladislas called his commanders to council and they all agreed the time had come to fight. In truth, they had no real other option. The ground to the north of Varna was hilly and rugged and impossible for an army to traverse. The Black Sea and Lake Devno to the south formed a narrow, marshy isthmus that was just as uninviting. Furthermore, there was still no sign of the Venetian fleet, meaning no evacuation or resupply would be available to the army.

After months of endless marches and gruelling sieges, the crusaders were also eager to finally come to grips with the enemy. Ladislas brimmed with the confidence and exuberance of youth, and he surrounded himself with a retinue of young Hungarian and Polish noblemen, all just as headstrong and idealistic. Hunyadi was also confident. The conditions in which he had to fight were far from ideal, but he had been in tough spots before and he was yet to lose a battle to the Ottomans. “To escape is impossible, to surrender is unthinkable,” Hunyadi declared at the council of war. “Let us fight with bravery and honor our arms!”

The order to prepare for battle in the morning rang out through the crusader camp. Cesarini gave a final mass in which he promised those who fell in battle a place in heaven. That evening Ladislas sent 5,000 horsemen to keep watch on Murad’s forces camped to the west and report on any movement. As the scouts peered into the darkening night, they could see the huge Ottoman bonfires licking the sky and hear the ominous rumbling of their war drums. Both armies slept that night in their armor and with their horses saddled.

One hour after sunrise Murad broke camp and began deploying his forces in a wide concave arc that stretched for five and half miles across the plain approaching Varna. His strategy was to use his numerical superiority to envelop the crusaders. On his left he deployed the army of Rumelia under Beylerbey Sehabeddin, while on his right he placed the army of Anatolia led by his son-in-law Beylerbey Karaca. The Anatolian and Rumelian troops were composed mainly of sipahi cavalry, although both were also screened by a line of azab light infantry. The sipahi were in many ways the Ottoman equivalent of the Christian knights in that they were a feudal levy that was granted fiefs in exchange for military service. They carried swords, lances, bows, and shields and wore a combination of plate and mail armor. When called to war, they brought with them their own retainers who they themselves armed. The azabs were armed with halberds, maces, sabers, and bows.

Murad positioned himself on a low hill in the center of the Ottoman line. Below he placed a line of azabs, as well as his janissaries. The janissaries were the elite of the Ottoman military, easily distinguished from other units by their tall felt caps. They were slave soldiers who had been snatched from their Christians families in the Balkans and raised to be devoted warriors of the sultan and of Islam. They were extremely skilled hand-to-hand fighters and carried a range of weapons, including bows, swords, shields, spears, and knives. Some carried arquebuses, the early gunpowder weapon that was inaccurate from a distance but deadly at close range.

Despite this clear numerical advantage, the sultan was not taking any chances. He knew Hunyadi to be an extremely talented commander, and he also knew from experience how wary his troops could be particularly when facing heavily armored Christian knights. At the base of the hill, Murad ordered a trench dug and lined with iron stakes. As a further precaution, he also placed at the top of the hill 500 camels laden with sacks of gold and rich silks. Should his position be comprised, these sacks were to be cut open, creating a distraction that would give him time to escape.

Hunyadi was indeed an exceptionally talented commander. He immediately recognized Murad’s envelopment strategy and planned accordingly. He deployed his forces in a convex formation two miles outside of Varna at a point where the plain narrowed between the marshlands to the south and rough high ground to the north. His strategy was to pin down the Ottoman flanks and funnel their troops onto the plain where their superiority in numbers would be negated and the heavily armored crusader cavalry had the advantage.

On his left by the marshlands he placed his Transylvanian troops under the command of Szilagyi. These were the hardiest and most experienced of his forces, veterans of the Long Campaign and innumerable other battles and skirmishes with the Ottomans. Most were light or medium cavalry units, highly mobile and used to fighting in the difficult terrain of the Carpathian frontier. The infantrymen were armed with swords and long halberds for cutting down cavalry and well-protected by mail hauberks and iron helmets and gauntlets. The heaviest of the Transylvanian troops were the Saxons knights, who fought encased in armor from head to toe.

On the crusader right, below the high ground to the north, Hunyadi placed the Papal contingent under Cesarini, the Wallachian horsemen under the command of Mircea II, and most of his Hungarian heavy infantry. Hunyadi knew that the Ottomans would try to outflank him from the high ground and he gave the commanders on his right flank orders to prevent this at all costs. It was for this reason that he assigned some of his most heavily armed and armored troops to this crucial position. As the Ottoman horsemen struggled to maneuver down the high ground, they were to be pinned down by a wall of steel.

In the center of the crusader army were 4,000 troops under the command of Stephen Bathory, the Palatine of Hungary. Above them flew the crusader banner of St. George. These men included the king’s 500-man bodyguard, which was composed of heavily armored knights drawn from the cream of the Polish and Hungarian nobility. Their shields, banners, surcoats, and livery were emblazoned with a colorful assortment of heraldic patterns and imagery, representing some of the foremost families in Eastern Europe. Mounted astride massive, well-trained destriers and boasting the best arms and armor of the age, this small but elite force was the mailed fist of the crusader army. It was Hunyadi’s intention to use it to tip the scales at decisive moments during the battle.

Behind the main crusader force, Hunyadi placed a defensive line of war wagons, crewed by experienced Czech mercenaries. These vehicles had come into popularity in Eastern European warfare following their use in the Hussite Wars that ended a decade earlier. Each wagon was a sturdy mini-fort in which three to four crossbowmen or hand gunners could fire in relative safety through portholes in the reinforced wooden sides. When strapped together in a square or long line, the war wagons proved a surprisingly difficult defensive fortification to overcome and could do much to strengthen a weak or outnumbered battle line. They also provided his outnumbered troops with the psychological assurance that there was a defensive line to fall back to should the battle not go their way.

For three hours the two sides watched each other deploy. During this time the weather remained calm and tranquil. Just as the two sides appeared ready to come to blows, a fierce wind suddenly blew across the plain from the sea, snapping the poles of the majority of the crusader standards. Among the few poles that remained unbroken was that bearing the standard of St. George. Many crusaders saw this as an evil portend of what was to come, despite immediate reassurances from Cesarini and various priests that it was indeed a good sign. Murad must have also seen this as a bad auspice for the crusaders because he immediately gave the order to attack.

The first into battle were the azab irregulars who raced ahead of the main Ottoman forces to harry the crusaders and goad them into breaking formation. As they advanced, the entire Ottoman line erupted in a deafening din of blaring horns, crashing symbols, thundering kettle drums, and resounding cries of “Allah Akbar.” The crusaders responded by crossing themselves and sounding their own trumpets and battle cries.

The Saxon knights on Hunaydi’s left were the first to respond to the enemy’s provocations. Ignoring Szilagyi’s orders to keep formation, they burst from the battle line and easily smashed through the lightly armed azabs. Following the irregulars were the well-trained and disciplined sipahis. When they saw the heavily armored Saxons coming right at them, they expertly parted their ranks to let them pass through, then surrounded them and attacked from all sides. They hacked and slashed furiously at the encircled knights only to discover that their light cavalry sabers could not penetrate the Saxons’ heavy plate armor. The Saxons in turn took a fearful toll on the Ottoman horsemen, skewering many with their long lances and hewing down many more with their double-edged swords.

Szilagyi led the rest of the Crusader left in an attack to save the Saxons. Unfortunately, such was the Ottomans’ superiority in numbers that soon he too was on the verge of being enveloped. Hunyadi saw this and he ordered Mircea to break from the crusader right and rescue the erstwhile rescuers. The wily Wallachians had a seething hatred for the Ottomans with whom they had been in almost constant conflict for over a century, and they took to their task with enthusiasm. What they lacked in armor they made up for in reckless bravery and remarkable horse archery. Astride their nimble mountain ponies, they weaved through the Ottoman ranks, unleashing rapid but lethally accurate volleys of arrows from their powerful bows.

Mircea’s fierce attack successfully restored the situation on the crusader left; however, it also weakened the right wing where the Ottomans had managed to maneuver up the high ground and were now pouring down the slopes, azabs in the lead and sipahis close behind. The crusaders dug in their spears and halberds and received the attack as best as they could but were quickly overwhelmed by the size and speed of the enemy force bearing down on them. More and more men began fleeing toward the safety of the war wagons. As they fled, they crashed into advancing comrades, creating panic and confusion.

For a time it looked as if the whole right flank was in danger of collapsing. In some places, the sipahis even managed to break through the line entirely and reach the war wagons where luckily they were temporarily halted by fire from the Czech mercenaries. The Ottoman left was composed of the sultan’s Rumelian troops who were more seasoned in fighting Christian armies. They knew from bitter experience that their swords and spears were useless against the heavy crusader armor and instead turned to the concussive force of their maces and war hammers. Some of these bone-shattering weapons also had flanged edges or sharp spikes that could bite through an iron helmet and a man’s skull along with it.

The Turks captured four crusader banners before Cesarini managed to rally 200 men for a desperate stand beneath the banner of St. Ladislas. They formed a hedgehog with knights and infantry in front and archers and crossbowmen behind. While units all around them fled in disorder, they stood like a breakwater, deflecting wave after wave of enemy attacks. At one point, 3,000 Ottomans bore down on them, but still they held their position and the banner of St. Ladislas continued to billow defiantly overhead. Hunyadi eventually noticed the desperate situation and reacted accordingly. He led a portion of the king’s bodyguard in a counterattack that temporarily thwarted the Ottomans.

While Hunyadi was desperately trying to restore order on the crusader right, the situation on the left was actually beginning to swing in his favor. His Transylvanian veterans, used to the Ottomans’ fighting methods, had parried every attempt at encirclement and refused to give chase to any of the enemy’s feigned retreats. Frustrated and having suffered heavy losses, Beylerbey Karaca’s men began to lose heart and leave the field. Karaca refused to join them. He let out a bellowing battle cry, spurred his horse forward, and charged straight into the enemy line, no doubt hoping to inspire his fleeing men to do the same.

It was an incredibly courageous act but ultimately counterproductive. After a brief struggle, a crusader knight killed Karaca. The sight of their commander being felled took the fight out of the remaining Anatolian troops and they began to flee. Hunyadi noticed this and took advantage of the situation to transfer troops from his left wing to his right where the battle was once again raging fiercely. Ladislas also committed his full bodyguard, and together with Hunyadi they made a thundering charge that smashed through the attacking Ottomans and drove them back up into the high ground. The crusaders pursued them for a few miles then returned to the plain.

A lull occurred in the fighting at that point. It was late afternoon and both sides were utterly exhausted. The battlefield was a charnel ground. Bodies lay everywhere, many hideously mutilated by the intense close-quarter hand-to-hand fighting. The ground itself had been completely torn up by the thousands of men and horses crisscrossing in all directions, and it was littered with discarded weapons and armor. As the tumult of battle subsided, the wails and groans of the wounded filled the air, which reeked of the acrid combination of blood, sweat, filth, and gunpowder. Hunyadi himself had been slightly wounded in the head by an arrow that had managed to partially pierce his helmet.

Ladislas, Hunyadi, and the other crusader commanders met behind the wagon line to discuss their next moves. At first glance, it appeared that they had won a spectacular victory. Both Murad’s right and left wings were in retreat and he had suffered ghastly casualties; however, the crusaders had also suffered mightily. Given that they had been significantly outnumbered to begin with, they felt their losses even more acutely than the Ottomans did. Moreover, the crusaders’ mounts were either dead or spent. A great many had been killed or wounded and those that remained were worn out from the terrible strain of rushing around the battlefield for hours with heavily armored riders on their backs.

Hunyadi urged the king to rest his men then reform his lines and wait for Murad to make the next move. He had been in similar situations before and knew that so long as the crusaders held firm, the stilted Ottoman attacks would eventually peter out, forcing the sultan to either sue for peace or retreat back to Edirne. It was prudent advice, and though the crusaders had no way of knowing it for certain, it was actually completely accurate. Across the battlefield, a despondent Murad was indeed preparing to rally what was left of his scattered forces and withdraw.

Unfortunately, young Ladislas had fallen victim to his own vanity and the misguided advice of his bodyguard. They had not incurred as many casualties as the other crusader units and were emboldened by the seeming ease with which they had put the Ottoman left wing to flight. They were also jealous of Hunyadi’s influence over Ladislas and his position as commander in chief of the crusader army. They convinced the king to seize the initiative and launch one more glorious attack directly on Murad’s position. Otherwise, it would be Hunyadi who would receive the credit for the victory and perhaps even the entire crusade.

When Hunyadi heard what Ladislas was planning, he was aghast and pleaded with him to reconsider. The king would not hear it. Instead he rode out with his bodyguard to a point in the plain looking directly out on Murad’s position and arrayed his men for a charge. Though they were relatively few in number, they must have looked resplendent on the open plain with their armor glistening in the sun, banners and livery blowing in the breeze, and lances and swords cutting the air. When he was satisfied with the formation, Ladislas drew his sword and spurred his horse forward.

With king in the lead, the crusaders advanced at first at a trot, then a canter, then finally broke into a full gallop. The pounding of their horses’ hooves was like a rolling thunder on the plain, which had fallen surprisingly quiet since the battle subsided. All eyes, Christian and Muslim, were fixated on this incredible display of martial prowess and chivalric tradition. Ottoman scribes would later describe how the dust cloud thrown up by the crusaders’ mounts was so great that it blotted out the sun.

Watching from his fortified hill, Murad could hardly believe his eyes at what he was witnessing. He was at the same time terrified of this deadly new threat bearing down on him and shocked that Ladislas would so recklessly gamble his own life. As the crusaders charged up the plain, they easily scythed through the few fleeing Ottoman troops in their way. The closer they got the more nervous the sultan became. Finally, his nerves gave out and he pulled on his horse’s reins to turn and flee. To his horror, the horse would not move. He looked down to find one of his veteran janissaries tightly holding the reins. The sultan and members of his staff screamed at the man to let go, but he stoically refused.

Ashamed and emboldened by this astonishingly courageous act of indiscipline, Murad regained his nerve and ordered his men to stand firm. No sooner had he done so than the crusaders plunged into the first line of azabs at the base of the hill. The irregulars stood no chance against the heavily armored knights. Many were simply trampled like grass by the crusaders’ massive mounts. But behind them was the stake-lined trench, which forced them to slow down and maneuver awkwardly. At the same time, from higher up the hill, the janissaries opened fire with their arquebuses. The four-ounce lead balls tore through the attackers’ armor causing ghastly wounds and knocking many from their horses.

Ladislas was unscathed by the arquebus fire. He led the way through the trench, up the hill and into the tightly packed ranks of janissaries. The sultan’s elite lived up to their hard-earned reputation. They did not retreat or even buckle in the face of the crusader’s relentless attack, but instead fell upon the outnumbered enemy in a savage frenzy of violence. They hacked, hammered, slashed, and stabbed at the knights from all sides, even pulling many from their saddles with their bare hands and pummeling them to death on the ground. The crusaders fought just as ferociously and showed no signs of abatement despite their dwindling numbers. In the cramped fighting, their sword strokes cleaved the enemy apart two at a time, showering their bright livery with blood and gore.

Amid the dust and smoke, Ladislas spotted Murad sitting atop his richly caparisoned horse in his own glittering battle armor, and he charged right at him. The sultan’s heart surely must have skipped a beat at the sight of Ladislas coming for him, bloody sword in the air ready to cut him down. But when the two were mere yards apart, another of Murad’s veteran janissaries stepped between them with a battle axe in hand. He waited until the final moment then, with a skill and focus only the most battle-hardened of warriors possess, hamstrung the king’s horse mid-stride, sending him crashing to the ground. Ladislas tried to rise, but the weight of his armor, and probably numerous broken bones, rendered him helpless. With a single stroke of his axe, the janissary cut off his head then presented the gruesome trophy to Murad.

Even before Ladislas was killed, Hunyadi could see he was in trouble and rode out to save him. He was prevented from doing so by some Ottoman troops who had heard the cries of triumph from the sultan’s position and had returned to the field with renewed fury. Hunyadi fought them off until sunset then fled north into the hills, rallying isolated groups of crusaders along the way. The victorious Ottomans pursued him for a number of days, leaving a grisly trail of dead crusader stragglers in their wake. Back at Murad’s position, the king’s bodyguard was butchered to a man and Ladislas’s head was fixed on a pike and displayed for all to see.

After watching Ladislas and his bodyguard gallop off to face the sultan, much of the crusader army assumed that the battle was won and set up camp behind the wagon line. It was only the next day when the entire Ottoman army appeared before them, Ladislas’s head waving in the air, that they realized the battle had been lost. In one great rush, the Ottomans overwhelmed the defenders, bringing the crusade to a close at last. Of the crusader commanders, both Cesarini and Bathory were slain. Mircea and Szilagyi fought their way out and rejoined Hunyadi in the flight back to Hungary. Meanwhile, Murad strode triumphantly into Ladislas’ tent, plunged his sword into the king’s throne, and fell to the ground to offer a prayer of thanks.

The battle of Varna was the last major effort by the Christian powers to expel the Ottoman Turks from Europe, and their defeat had enormous consequences for the peoples of the Balkans. Nine years after the battle, Constantinople fell to Murad’s son Mehmed, who also overran Serbia and Wallachia. Mehmed probably would have driven into Hungary as well were it not for his defeat at the hands of Hunyadi at the Battle of Belgrade in July 1456. Hunyadi died of plague the following month, but the resulting peace finally stabilized the frontier and ensured peace between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire for the next 70 years.