By John E. Spindler

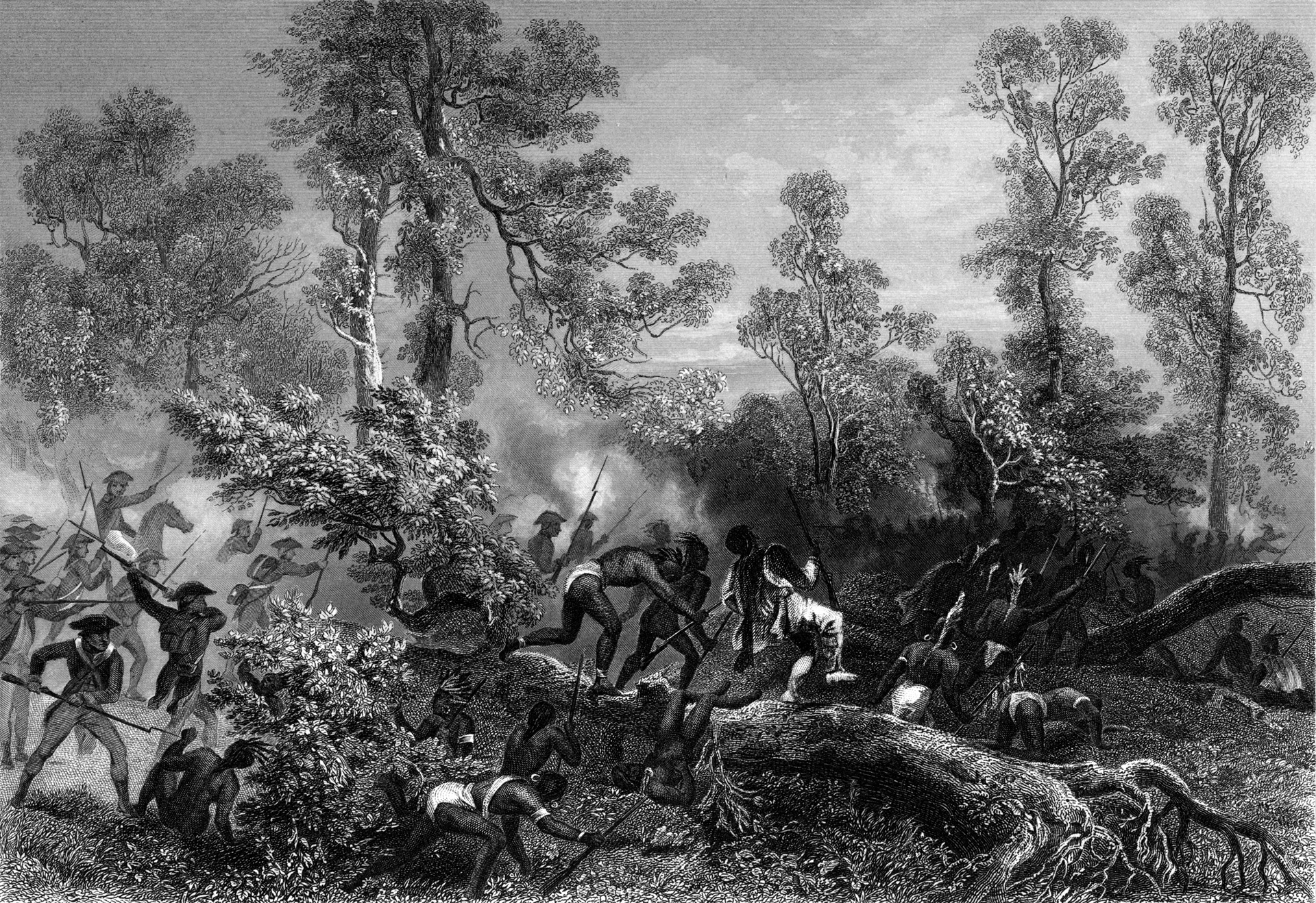

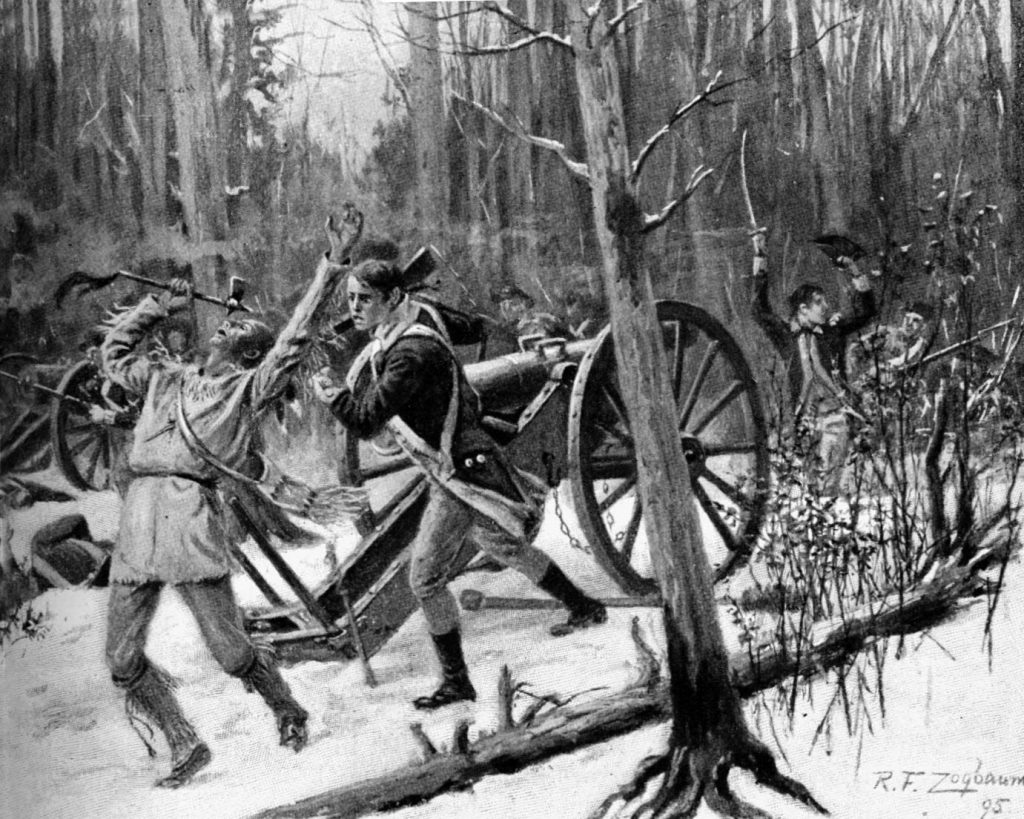

The warriors of the Western Confederacy crept silently along the snow-covered ground towards the U.S. Army camp on the banks of the upper Wabash River just before dawn on November 4, 1791. Their faces were painted red and black. The war paint was not only intended to frighten their foe, but also to protect the warriors in battle. The warriors were armed with clubbed weapons, such as hatchets and tomahawks, as well as missile weapons such as bows and captured muskets.

When their war chiefs gave the signal to attack, the warriors rushed forward screaming their blood-curdling war cries. While two bodies of warriors swept around the camp to encircle it, the main force made a frontal assault. The mostly inexperienced soldiers under the command of Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair were just restarting their fires from the previous day when the Native Americans penetrated the army’s exposed militia camp.

Caught by surprise, the militiamen fled in panic. Those who were not cut down fled in terror through a freezing-cold stream in a desperate effort to reach the main camp before being overtaken by the bloodthirsty warriors. Back at the camp, regulars and volunteers rushed to grab their weapons and shake themselves into a line of battle to stem the unexpected onslaught. St. Clair’s army was in desperate straits. Whether the general could rally his troops and repulse the warriors of the Western Confederacy was at that point highly doubtful.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 had brought an end to the American Revolutionary War and delineated the boundary in North America between British crown lands and the 13 states. Through the treaty, the British Empire ceded all territory east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of the Great Lakes to the newly independent United States. In addition, the British agreed to relinquish various forts across the northern boundary. Yet they surreptitiously continued to occupy and use these fortifications, particularly Fort Detroit, to furnish aid to the Native Americans.

The British handed over this vast territory without consulting, or even informing, the Native American tribes, many of which had allied themselves with the British against the Americans. Several tribes refused to accept U.S. sovereignty. Although the conflict between the various tribes and westward settlers had been ongoing since 1750, the stakes for both sides increased in the aftermath of the founding of the United States.

In the 1780s the Confederation Congress, America’s legislative body, lacked the authority to tax for desperately needed funds. The U.S. government was an estimated 40 million dollars in debt from the Revolutionary War. The Congress hoped to sell some of the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains to raise money to pay off the new nation’s debts. The legislative body set forth regulations concerning surveying, selling, and settling lands north of the Ohio River in the 1785 Land Ordinance.

A force was needed not only to deal with squatters occupying land in the Northwest Territory, but also to protect the settlers from violent responses by the Native Americans. With an inherent suspicion of standing armies, the Confederation Congress had previously authorized the creation of an army not to exceed 700 men. The legislators appointed Brig. Gen. Josiah Harmar in 1784 to command the army. To supplement the regular army, the legislators continued the British tradition of maintaining a home militia. It just so happened that the 13 states, as well as the Kentucky district of Virginia, already had militias.

During this time, government representatives had been attempting peace negotiations with the Native American tribes west of the Alleghenies. Unfortunately, the large number of tribes meant several treaties, each negotiated with only a few tribes. The U.S. government assigned Maj. Gen. Richard Butler the arduous task of negotiating the treaties. He worked out settlement boundaries in three key treaties; however, none of the primary tribal chiefs signed these treaties. Cultural differences regarding how the land was used ensured the two sides would clash. As Native Americans used the land for hunting and gathering, they could not comprehend the idea of measuring land to be parceled out for private ownership so that American settlers could cultivate the land for both sustenance and profit.

The treaties did not end raids by Native American warriors. In a never-ending cycle, the Kentucky militia retaliated in response to a raid by crossing the Ohio River to raze villages of tribes such as the Shawnee, Delaware, and Miami residing in the Northwest Territory. In the midst of these skirmishes, important events occurred back East. With the plan to sell the land a failure, the Northwest Ordinance was enacted on July 13, 1787. This legislation guaranteed settlers the same rights that citizens of the 13 states possessed. The ordinance also established a system by which settlers in the territory could form new states. The same year saw the foundation of a new national government with the drafting of the U.S. Constitution.

General George Washington was elected the nation’s first President and immediately faced many difficult tasks. Among them were the continuing confrontations between Native Americans and settlers. The settlers feared purchasing land because of the lack of guaranteed protection. Land speculators saw loss of their investments and wrote to President Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox, stating that the only way to persuade people to settle in the Northwest Territory was to eliminate the tribes though force.

Brig. Gen. Harmar advanced north towards Kekionga on October 7, 1790. Leaving Fort Washington—located near Cincinnati on the Ohio River—he marched north with 320 regulars of the 1st U.S. Regiment, 1,133 militiamen, and three artillery pieces. Although this was the largest army the Western Confederacy had seen, the majority of militia were not the veteran frontiersmen. Many were actually young boys and old men who had never fired a musket.

Harmar arrived at Kekionga, only to find the Miami had burned their own structures in order to prevent the Americans from using them. A large supply of vegetables and corn was found there and in smaller villages in the vicinity. The Americans torched the food stores. The process was repeated the next day at Chillicothe, a Shawnee village a couple of miles away. After razing Kekionga, five villages and an enormous supply of food, Harmar declared victory and returned to Fort Washington. He twice sent detachments numbering several hundred men to confront any returning Natives; on both occasions, the detachments were severely mauled by Native ambushes. Harmar’s campaign ended in failure with the loss of 73 U.S. regulars and 100 militiamen killed.

The Native Americans of the Western Confederacy launched vicious retaliatory raids in January 1791 from their principal settlement of the Glaize, a trading community situated where the Auglaize River empties into the Maumee River. On January 2, a Native American force raided the settlement of Big Bottom near Fort Harmar, and on January 10, Mingo leader Simon Girty directed an attack against Dunlop Station, 17 miles north of Cincinnati.

The raids caused panic and reluctance for westward movement among American settlers. They also showed the Native Americans that they did not need a major military victory to slow or stop American expansion westward. Increased pressure by elite land speculators forced President Washington to act. Washington appointed Northwest Territory Governor St. Clair on March 4, 1791, to command the next expedition with the rank of major general.

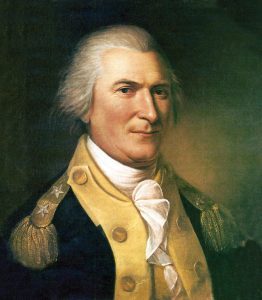

Scottish-born St. Clair had purchased a commission in the British Army and fought in the French and Indian War in North America. After resigning his commission, he stayed in North America. Joining the Continental Army in January 1776, he rose through the ranks, being promoted to major general in February 1777. As commander of Fort Ticonderoga, St. Clair made the questionable decision to withdraw its small force without being under fire from the British. Although exonerated at his court-martial, he never again held a command post. St. Clair went into civil service after the Revolutionary War’s end. His health was compromised by obesity and gout, the latter of which worsened with extended exposure to dampness and cold.

His second in command was Maj. Gen. Richard Butler. A former trader who had married a Shawnee woman, he knew personally many of the war chiefs of the Northwest Territory tribes. Other important subordinates included Major John Francis Hamtramck, commanding officer of the 1st U.S. Regiment; Major Jonathan Heart, acting commander of the 2nd U.S. Regiment; Lt. Col. William Darke, commander of the 1st Levy Regiment; Lt. Col. George Gibson, commander of the 2nd Levy Regiment; and Lt. Col. William Oldham, commander of the Kentucky militia.

Ordered by President Washington to launch a more forceful campaign in the summer, St. Clair’s hopes were buoyed by Congress’ approval of an additional regiment and the authorization to raise another 2,000 men on six-month terms. Unfortunately, the regular regiments never achieved the authorized strength of 950 men and officers, and the recruitment drive failed to attract the desired number of volunteers.

American soldiers were armed with Charleville muskets that had been supplied by the French during the Revolutionary War. These muskets fired a .69-caliber lead ball and had a maximum range of 1,000 yards. Providing firepower were two artillery companies. One possessed four 3-pounder cannons, while the other was armed with four 6-pounder guns. One hundred mounted dragoons accompanied the force to provide reconnaissance and guard the army’s flanks.

Originally scheduled to depart mid-July, the U.S. Army that finally departed Fort Washington was about 1,600 officers and men, 80 artillerymen and 100 dragoons. More than half of the troops were in the 1st and 2nd Levy Regiments on six-month terms; a majority of those men had never been in the woods before or even fired a firearm.

St. Clair had to supplement his force with militia. He anticipated assistance in form of 1,300 militiamen from Kentucky and Pennsylvania, but only a meager force of about 400 militiamen, mostly untrained volunteers, materialized.

Two confederations vied for control of the area that constituted the Northwest Territory in the 1780s. On one side were the 13 states governed by the Confederation Congress, which saw the land as the solution to its financial difficulties. Opposing were numerous tribes, each the equivalent of an independent nation. During times of crisis, such as in 1790, these tribes formed confederations, usually consisting of tribes who saw the need for cooperation and affiliation transcending cultural and language differences. Other times an outside source, such the colonization of America, drew tribes together to face a common danger.

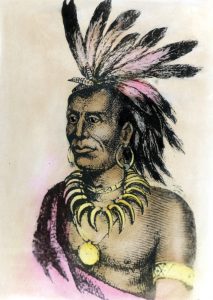

The primary leaders behind the Western Confederacy were the war chiefs Mihsihkinaahkwa (also known as Little Turtle) of the Miami, Weyapiersenwah (also known as Blue Jacket) of the Shawnee, and Buckongahelas of the Delaware. Fighting alongside, from the Great Lakes, were the Ottawa, Potawatomi and Ojibwe, also known as Chippewa, who had already formed an alliance known as the Three Fires. The Wyandot, along with a few Cherokee and the Mingo, also believed in the need to stop the settlers’ encroachment.

Unlike the conventional military structure employed by the Americans, the Native confederation army did not use a formal command system. War chiefs with charisma and strong character, such as Weyapiersenwah and Mihsihkinaahkwa, held their positions because warriors believed in and followed them. A council of tribal leaders would debate and then agree on a general strategy and tactics, but the warriors, all of whom were volunteers and free to leave at any time, generally fought individually once a battle began.

Continuing an informal alliance, the tribes were supplied provisions and firearms by the British out of Fort Detroit. At the Battle of the Wabash, the Western Confederacy warriors fought with weapons of various calibers. Probably the most common was the British .75-caliber Brown Bess musket, which was similar to the Charleville musket in range, accuracy, and reliability. When the powder and shot for their firearms was gone, the warriors reverted to traditional bows and tomahawks.

In summer 1791, the Western Confederacy fielded what was likely the largest Native American army assembled up until that time. Ensign Samuel Turner, a prisoner being taken to Fort Detroit, stated he had heard the army, under the control of Blue Jacket, was 1,500 strong with another 900 men approaching the area. William Wells, taken captive and then adopted by the Miami tribe as a child, said that Little Turtle commanded an army that consisted of 1,400 men, of whom 1,133 fought that morning. Simon Girty noted that he had counted 1,040 warriors who departed the Miami villages on October 28. “The Indians were never in greater heart to meet their Enemy,” Girty wrote to a British Indian agent

With his appointment, St. Clair also received advice from Washington. The president told him always to be alert for surprises, stay armed, and fortify at night. St. Clair’s campaign instructions declared that he was to march north, no later than July 10, from Fort Washington to the Miami villages at Kekionga.

After subduing any resistance, St. Clair was to construct a fort with a garrison of 1,200 men. This would allow the U.S. to exert control in the area and counter British influence. In addition to the veteran 1st U.S. Regiment, he would have at his disposal the newly raised 2nd U.S. Regiment. These two units totaled 1,000 regular troops. Knox authorized the recruitment of 2,000 levies on a six-month term.

A couple of days after leaving for Fort Pitt, the assembly point in the East for men and supplies going to Fort Washington, St. Clair experienced a severe gout attack. Campaign responsibilities temporarily devolved to Butler. St. Clair reached Fort Washington on May 15 and met the 299 men from the 1st U.S. Regiment, around which he built his army.

U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton arranged for the United States to finance the campaign. However, the contract system in place to supply the U.S. Army was corrupt and inefficient, meaning that everything an effective army required was supplied by the lowest bidder regardless of quality or suitability. In January 1791, the U.S. Army awarded the contract to financier William Duer, a friend of Secretary of War Henry Knox. Given $75,000 by Hamilton for the operation, Duer proceeded to loan out $10,000 of the first $15,000 installment to Knox for land speculation in Maine. He also misappropriated funds pay off his own debts.

In the same month Washington appointed St. Clair, Knox appointed business partner Samuel Hodgdon to be Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army. Hodgdon has been described as lacking common sense and good judgement, which would prove to be detrimental to Maj. Gen. St. Clair and his army. His responsibilities included dealing with supply contracts and inspection of those supplies in Philadelphia. Hodgdon was also tasked with organizing the transportation of the supplies to Fort Washington.

Hodgdon apparently felt immune to any repercussions from ignoring deadlines, and he did not arrive at Fort Washington until mid-September. In his absence, St. Clair was forced to waste time in locating and employing a variety of local craftsmen in Cincinnati, including gunsmiths, carpenters, and wheelwrights.

Butler lodged a number of complaints regarding Hodgdon’s poor management and the general neglect by his department. Almost the entire materiel inventory was of low quantity and poor quality. Firearms were in a poor state, with some unusable. Tents were of material that leaked in heavy rain. The powder casks for the cannons leaked, rendering some powder useless due to moisture contamination. Worse still was the lack of powder cartridges for the muskets, which prevented target practice for the new recruits and volunteers.

The situation was further exacerbated by a summer drought that caused the Ohio River water levels to drop, preventing the shipment of men and cargo. Not until mid-August did transports regularly sail down the river. When the last of the troops arrived in mid-September, there was no time for training the new men.

St. Clair knew he needed assistance from the Kentucky militia and their commander, Brig. Gen. Charles Scott. Scott had led a mounted force across the Ohio on May 23. During this incursion, the mounted troops had destroyed Wea villages along the Wabash at Ouiatenon. As result the tribes turned to the British, requesting food and munitions for the invasion they had known about since early April. Not surprisingly, the British agreed to help.

While a second Kentucky militia raid was returning, St. Clair moved a portion of his force north six miles to Ludlow Station. He wanted to remove the temptations of vices from the soldiers in Cincinnati. Those who had volunteered or enlisted were mostly the poor or those with a criminal history; it was difficult to instill discipline on such men. Mainly from urban areas, most of these men had never been in the woods before, and many would only fire a weapon for first time on the march northwards.

At the end of August, St. Clair visited Kentucky to negotiate the employment of the militia. Scott was reluctant to allow his best men to go, so St. Clair received slightly more than 300 poorly trained militiamen under Oldham. Upon returning, St. Clair found Butler, and the last of the troops arrived. He had the army march 18 miles north from Ludlow Station, building a path known as St. Clair’s Trace.

Construction of the supply depot known as Fort Hamilton along the Miami River proceeded throughout September. In contrast to the summer drought, September saw an overabundance of rain and the start of desertions. Returning to Kentucky to supervise the militia, St. Clair left orders for Butler to proceed north after completion of Fort Hamilton. The army was to march in two columns on a pair of 40-foot wide paths and encamp at night in rectangles, with the columns forming the long sides and the noncombatants secured in the middle. In contrast to the Native Americans’ knowledge of the army’s location at all times, St. Clair’s force advanced blindly.

With Fort Hamilton built, Butler began the army’s advance on October 4 and only made it two miles before having to bivouac for the night. The men discovered that their uniforms fared poorly in the autumn weather. Over the next few days, the army made progress, but carving out two paths through wooded terrain was slow work. Due to Hodgdon’s mismanagement, too few felling axes were on hand. Butler ignored his commander’s orders and instead cleared a single path wide enough for the army. St. Clair arrived at Fort Hamilton on October 7 and was angered at the pace of the army, Butler’s decision to cut only one trail, and the lack of a flour convoy. The inconsistent supply of flour had severely hampered the speed of the advance.

The rains returned on October 12, and the troops awoke to the year’s first hard frost. With low provision levels, St. Clair ordered many of the civilians accompanying the army to head back to Fort Washington. The next day, St. Clair selected a site for another supply fort, to be named Fort Jefferson, which is situated near modern-day Greenville, Ohio. Despite the shortage of construction tools, the fort was finished in about two weeks. As morale waned from the weather, poor equipment, and continued lack of supplies, desertions continued unabated. Over the course of the advance to Fort Jefferson, a few soldiers were picked off by the enemy when they straggled.

On October 24, the army resumed its march, leaving 120 sick men and two cannons at Fort Jefferson. A couple of the days later the rain changed to snow. Further complicating the situation, the last of the flour was used up, and the force halted to await a supply convoy, which also brought the anticipated twenty Chickasaw scouts.

While the Americans were welcoming the flour convoy, the three war chiefs led their warriors south. Instead of hiding from the Americans as they did in 1790, the council made the bold decision to take the fight to the invaders.

A debate occurred on October 20 in the American camp as to whether to continue the campaign after those levies with expiring terms were released. It was decided to carry on the campaign, but non-essential baggage was sent back with the levies. After advancing 13 miles in a couple of days, the army encamped, and that night about 60 militiamen deserted. Fearing they might hijack the incoming flour convoys, 300 men from the 1st U.S. Regiment, under Hamtramck, were sent to ensure the convoys’ safety. One convoy arrived, but a second was expected. Uncertainty arose over whether it still existed, and the regiment tried to locate it. This decision would deprive St. Clair of his most reliable men at the time when their experience was sorely needed.

St. Clair then suffered another gout attack, so the army did not resume its advance until November 2. Resuming the advance, the army eventually came across what St. Clair mistakenly believed was St. Mary’s River. He set up camp on a wide piece of high ground next to the Wabash River at the location of modern-day Fort Recovery, Ohio. No attempt to build even a rudimentary defense was made. The camp took its standard rectangle shape with the levy regiments under Butler forming a long side close to the river. Darke held the opposite side, and each side had three cannons. Butler was supported by the 6-pounders. A dragoon company and riflemen formed the short sides, with the civilian and baggage wagons protected in the interior. St. Clair assigned 220 men to six locations beyond the camp’s perimeter. With a lack of space and a justifiable concern over more desertions, the remaining companies of militia were forced to encamp 300 yards away, across the river.

At the onset of the advance, St. Clair had started with 2,000 men. Desertions, levy-term expirations, and the detachment of troops to guard the flour convoy considerably reduced that number. The adjutant general calculated the army and militia forces present on November 4 totaled 1,669 officers and men. “Discharges, desertions, and the absence of the first regiment reduced the effective strength on the day of action to about fourteen hundred,” wrote aide-de-camp Lieutenant Ebenezer Denny in his journal. Despite the strength reduction and lack of accurate intelligence, St. Clair still believed he had enough men to be victorious. He dismissed any enemy seen so far as opportunists, not scouts from an opposing army.

Just two-and-a-half miles from the American encampment were 1,400 warriors of the Western Confederacy. The council, kept well-informed of St. Clair’s position, made final preparations. The force was ready to attack the invaders the next day with morale running high.

That night, an American scouting party successfully ambushed a small party of warriors. Soon afterwards, a larger war party was spotted but not engaged. The scouts returned to the militia camp, where its commander informed Oldham. The lieutenant colonel sent him to report the findings to the main camp. Debriefed by Butler—since St. Clair had retired for the night—he was told to get some rest.

In pre-dawn prayers, Blue Jacket announced that the Great Spirit was with them. Due to a better job of self-promotion, Little Turtle has been seen as the mastermind of the operation. However, Blue Jacket is believed to have been the driving force, and he was the one who decided to attack using the crescent formation based on previous success. Forming the left horn of the crescent were 400 warriors from the Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi tribes. The right horn was composed of 300 warriors from the Wyandot, Cherokee, and Mingo tribes. At the crescent’s base were 700 warriors from the Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware tribes.

As the Native Americans moved into position for their attack at 5:30 am, the Americans reignited their cooking fires. Animal sounds were heard, and some even concluded that the sounds came from people rather than animals. Reveille sounded at 45 minutes later, and officers prepared for morning review. At last informed of the raid results, St. Clair met with Oldham. After review, the men gathered for breakfast with weapons nearby as a precaution.

As the sun rose above the horizon 30 minutes later, the Native American army advanced. By that time, they were arrayed in the crescent-shaped formation and had advanced to within 200 yards of the outermost militia. Minutes before they were spotted, a thousand war cries shrieked throughout the forest.

Near the militia camp, a pair of sentries fired upon some Native Americans. The Native Americans near them returned fire, sending hundreds of muskets balls at the startled sentries. The two men fled their positions. Within minutes large numbers of warriors swept around the camp to the north and south, while the Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware attacked it frontally.

The militiamen, who lacked a leader since Oldham was with St. Clair, only got off a few dozen shots. Some died as they tried to reload, while others, paralyzed by fear, were cut down. Most made the 300-yard dash to the main camp.

Alerted by the war cries and the sound of musket fire, the officers started to prepare the battle positions. St. Clair threw an old black coat over his bedclothes and donned a battered black hat. Dressing in those clothes saved his life. Although the Native American warriors tended to fight independently, groups of marksmen were assigned specific targets. At the direction of the British, one group of marksmen targeted the American officers, while another group focused on silencing the cannons.

As the officers started to rally the troops, the fleeing militiamen crossed the frozen Wabash River, climbed its ravine side, and continued straight into the army’s main line. Disruption reigned in the cannons as frightened militiamen stationed on both sides of the guns ran through them. These men infected some of the levies with their panic and tried to find safety amongst the civilians, but the women chased them out of the area. The Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware followed the militia closely, and some fought around the 6-pounders.

“In a few minutes, our whole camp, which extended above three hundred yards in length, was entirely surrounded and attacked on all quarters,” recalled St. Clair. While a bayonet charge temporarily stabilized the area around the cannons, in 30 minutes the warriors of the Western Confederacy had surrounded the Americans. By that time one-quarter of St. Clair’s men were either slain or had fled the battlefield. The general had two horses shot out from underneath him.

At 7:15 am the next phase of the battle began as the Native Americans brought a deadly crossfire to bear against St. Clair’s troops. Morale and discipline continued to disappear as men watched their officers being struck down. The cannons were virtually ineffective as they mostly fired over the heads of the attackers. Within 90 minutes, the artillery support had been silenced. The cannon fire was heard miles away by Hamtramck, and he pushed his men towards the noise.

An adrenalin surge brought about by the combat allowed St. Clair to direct the battle on foot without pain. In an attempt to stabilize the perimeter, he ordered Darke to lead a bayonet charge. The Wyandot warriors fell back in the face of Darke’s charge. When the counterattacking troops reached a gully, they were forced to halt. At that point, they began to take heavy casualties.

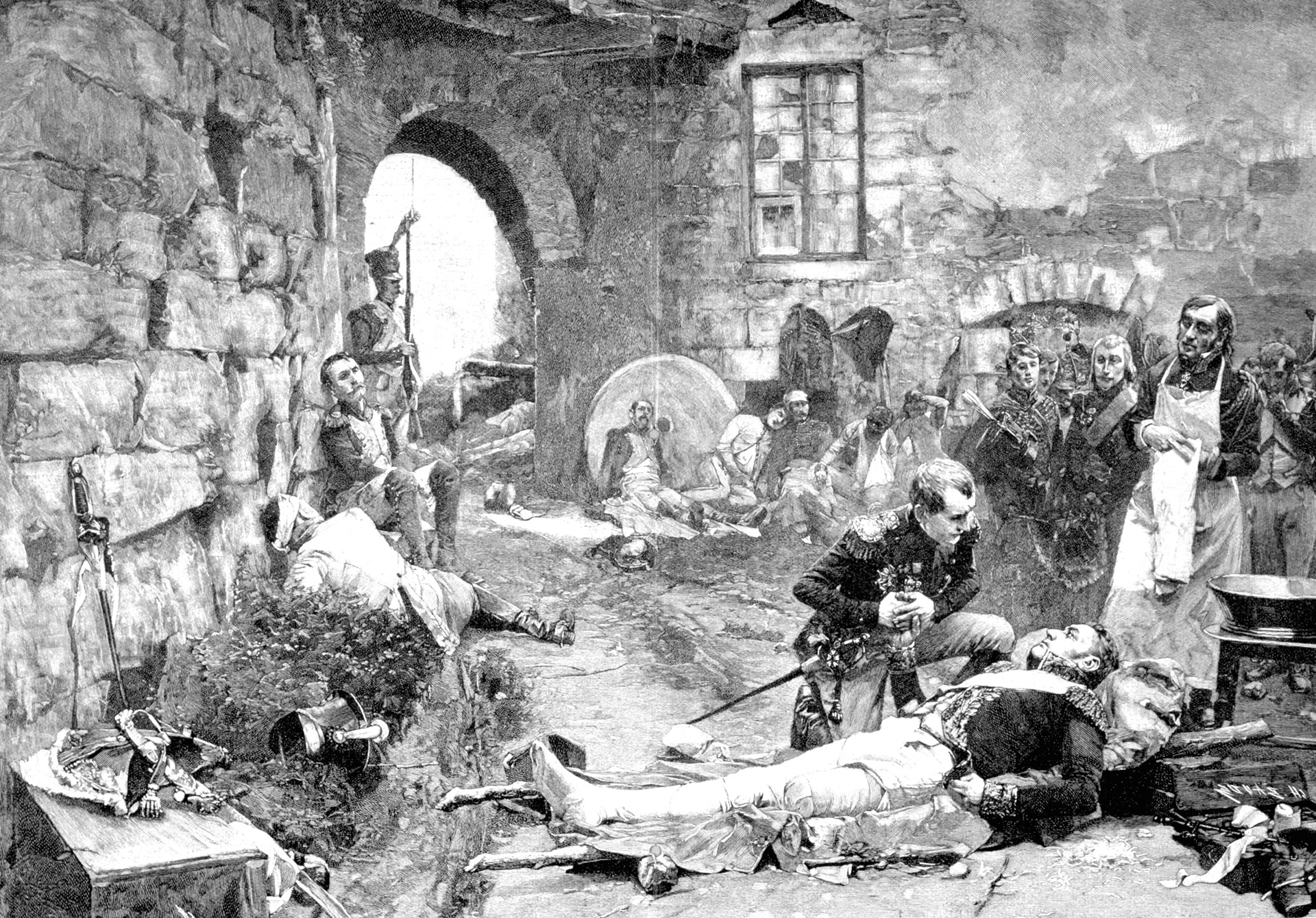

Taking advantage of the reduced U.S. forces, Shawnee warriors overran the dragoons next to Thomas Butler’s company, as well as part of the 1st Levy Regiment. Rallied by their chief, the Wyandot warriors followed Darke’s men back and joined the Shawnees’ attack as both tribes pushed into the heart of the camp. Warriors scalped and slaughtered the wounded, cowards and civilians. During the battle, a rifleman made the disheartening discovery that the gunpowder used by the Americans was too weak. He claimed that he hit several of the enemy, but they were not brought down. While ejecting the intruders from the camp, Darke was wounded.

While Darke made his charge, Butler and others conducted additional charges. During one of these Butler was severely wounded, and almost all of the 2nd U.S. Regiment’s officers were killed. In order to retake the camp’s southern end, St. Clair and Major Heart gathered some men from shattered units and charged. While successful in expelling the warriors by 8:30 am, casualties were heavy, including the death of Major Heart.

Butler and Darke took command of the front and rear lines, respectively. The situation was desperate as the Western Confederacy warriors had forced the Americans into a smaller area. There were hundreds of wounded, as well a significant number of men who were too demoralized to continue the fight. The warriors had quickly learned to melt away in face of the bayonet charges and then attack when the Americans pulled back.

Regrouped, the Native Americans attacked again using same pattern. Any surviving officers were targeted as the warriors advanced using trees and logs for cover. During this assault, Butler was mortally wounded. With the situation critical, St. Clair threw his last intact unit into battle. After laying down fire, another bayonet charged drove the Miami and Delaware fighters back down the ravine. Falsely believing he had outlasted the enemy and won the battle. St. Clair welcomed the lull in fighting.

Blue Jacket rode among the warriors to revitalize their spirit. After 15 minutes, they attacked again with renewed determination. The Americans realized they would have to abandon the camp’s southern section, where a dying Butler sat propped against a tree. The last remaining cannon was spiked and the mobile wounded removed as the troops relocated north. Shortly after this evacuation, the Shawnee, Miami and Delaware pressed forward. Butler was killed with a tomahawk. Some warriors ran out of powder and shot but continued to inflict death with arrows.

By 9:30 am the army had taken 50 percent casualties and St. Clair knew his force must retreat. Forming a plan, he had some units hold their positions while Darke supervised a charge to break the encirclement. Afterwards, the men would strike east and feint clockwise towards St. Clair’s Trace, then wheel in the other direction before making a loop to return to the path. Quickly the bayonet charge opened a gap in the enemy’s line. Those soldiers who could walk poured through the gap. St. Clair left the battlefield with the last of his men at 9:35 am.

But discipline soon evaporated. Men fled for their lives, tossing away their weapons and equipment in the process. The wounded who could not continue were abandoned. Warriors pursued the Americans for five miles before returning to the battle site. Some militia who fled at the onset of the battle ran into Hamtramck and informed him of the massive Indian attack. Fearing the worst, Hamtramck ordered the 1st U.S. regiment back to Fort Jefferson to prepare a defense. At the American camp, the Native American warriors took out their aggression upon the helpless wounded and civilians. His gout pain returning, St. Clair mounted a horse. He said the retreat was “disgraceful business.”

The lead elements reached Fort Jefferson, which offered little protection and was practically out of provisions, at 7:00 pm. A decision was made to march the 45 miles to Fort Hamilton. Leaving the immobile, St. Clair and his force departed at 10:00 pm. Stragglers stumbled into Fort Jefferson for a day or two, as did the Chickasaw scouts who had been away on a mission up the Miami River.

St. Clair knew his army had been roughly handled but not his exact losses. While sources give slightly differing numbers, the battle produced the highest-percentage casualty rate ever suffered by a U.S. Army unit. The Native American coalition had killed 632 of the 920 soldiers and wounded many others. Militia losses are unknown, but probably were similar to those of the regular army troops. St. Clair also reported the loss of six cannons, two baggage wagons, and 1,200 muskets.

The Native Americans looted the camp and slew most of the Americans. Some of the cannons were rolled into the Wabash. Unfortunately, any momentum that Little Turtle and Blue Jacket had gained from their victory soon disappeared. Differences in the council regarding a follow-up strategy, as well as poor crop yields, led to the disbanding of the Native American coalition army. Casualty figures among the Native American warriors have never been determined. Their losses are estimated at 21 killed and 40 wounded.

After a stop at Fort Hamilton, St. Clair and most of the demoralized survivors arrived at Fort Washington on November 8. Many soon left, but St. Clair stayed to write his after-action report. The report reached Washington, who was outraged upon hearing about the disaster.

In order to determine blame for the loss, the U.S. House of Representatives initiated an investigation, the first Congressional Special Committee investigation. After hearing witness testimony and reading evidence, the legislators exonerated St. Clair of all blame. He resigned his commission and returned to duty as territorial governor. The committee found that Secretary of War Knox, Quartermaster Hodgdon, and other War Department officials had done an inadequate of job of raising and training a sufficient force and had failed to equip and supply the army due to gross mismanagement and neglect. Although St. Clair’s ignorance of the area’s topography and geography complicated matters, the committee found he had remained cool and professional throughout the campaign, having to overcome ill-trained troops, poor-quality equipment, and supply shortages.

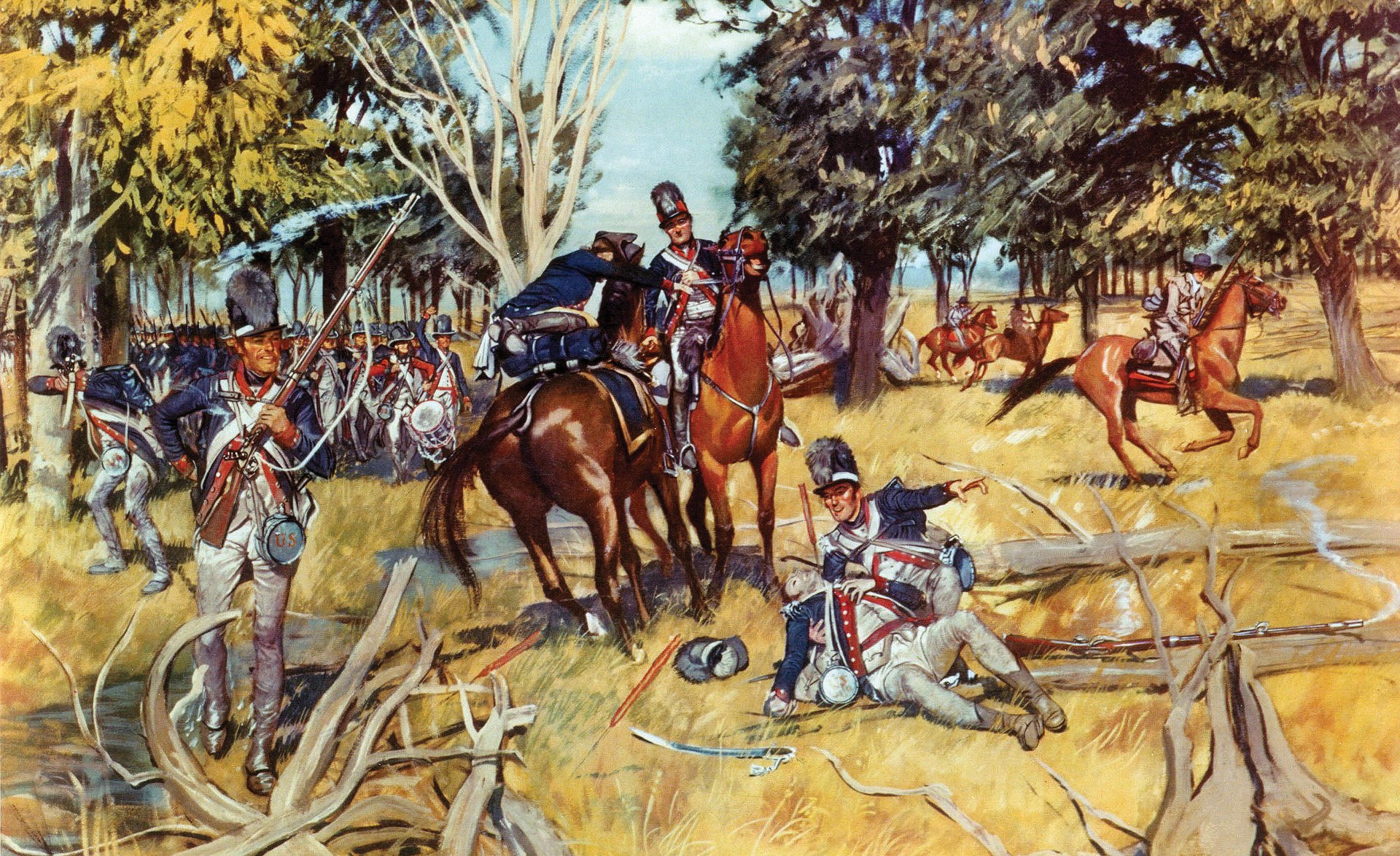

The silver lining that resulted from the defeat was the birth of today’s U.S. Army. Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne was appointed as its new commander, and Congress appropriated adequate funds for it. Legislation was passed to standardize organization, equipment, and training of militias to conform to that of the army. After the defection of William Wells—who developed an effective scout force—and Wayne’s training to fight the tactics of Native American warriors, Wayne returned to site of St. Clair’s defeat. Recovering the bodies, he built Fort Recovery.

In summer 1794, Wayne successfully defended Fort Recovery from a Western Confederacy attack. On August 20, 1794, he soundly defeated them at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The losses forced various tribes to sign the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, in which they ceded land south of Fort Recovery. This land became the boundary marker between America and the Northwest tribes.

On November 4, 1791, along the banks of the Wabash River in western Ohio, one of the most important battles in American history took place. Weyapiersenwah, Mihsihkinaahkwa, and Buckongahelas led a determined Native American army that was habitually underestimated by a government that believed too highly in its military’s capability. St. Clair, in poor health, performed the best he could with the forces and support he had at his disposal. The site of the worst defeat of an American force by Native Americans, even greater than the Battle of Little Bighorn, would have a positive consequence; that is, the birth and development of the U.S. Army.