By Joshua Shepherd

For the weary troops of the Army of the Cumberland, there was precious little sleep to be had in the farm fields and cedar thickets northwest of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. For four days, the men had battled driving rain and ankle-deep mud as they groped their way southeast from Nashville in search of their Rebel opponents. By the evening of December 30, 1862, the Federals were miserably camped, many without tents, on sodden ground that offered little comfort from the cold night air.

Senior officers fared little better. Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook, commander of the army’s right wing, was curled up in the corner of a rail fence when he was abruptly wakened a little after 2 am by two of his subordinates, Brig. Gens. Phil Sheridan and Joshua Sill. The officers, former roommates at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, were agitated; for several hours, Sill had listened as Confederate troops moved in the darkness across his front, heading, he was certain, to strike the army’s exposed flank.

A bleary-eyed McCook listened for some time then enjoined Sheridan and Sill not to worry. The right flank would hold just fine, he announced, and he further doubted “that there was a necessity for any further dispositions.” While McCook fell back asleep, Sheridan and Sill, disappointed that they had gotten nowhere with the wing commander, returned to their troops. It was not the first time, literally or figuratively, that McCook had been caught napping.

That October, commanding the left flank of the Army of the Ohio at Perryville, Kentucky, his wing had been the target of a Confederate surprise attack. McCook, whose command had been badly chewed up in the subsequent fighting, did little to improve his reputation. Ohio Colonel John Beatty regarded him as little more than an overrated “chucklehead” who was “deficient in the upper story.” The army’s overall commander, Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, fared even worse. Repeatedly prodded by the Lincoln administration to mount a vigorous pursuit of Confederate forces into eastern Tennessee, Buell obstinately refused, opting for a move toward Nashville in defiance of orders. Not surprisingly, Buell was unceremoniously dumped a few weeks later.

William Rosecrans vs Braxton Bragg

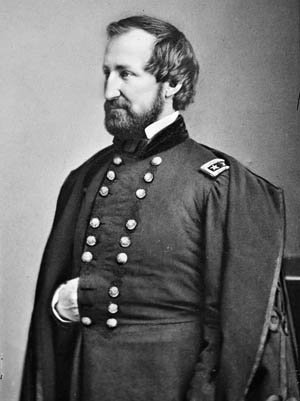

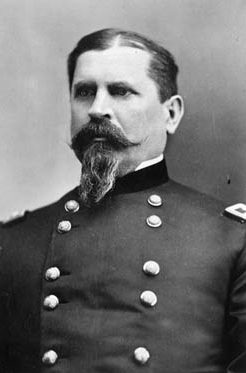

His replacement, Maj. Gen. William Starke Rosecrans, seemed a more promising choice. A West Pointer with impeccable academic credentials, Rosecrans had graduated fifth in the Class of 1842. Elite assignments to the Corps of Engineers and the West Point faculty followed. An Ohio militia colonel at the outset of the war, the Cincinnati-born Rosecrans went on to serve with distinction at Rich Mountain, Virginia, in 1861, and was eventually assigned command of the Federal Army of the Mississippi. While Buell floundered in Kentucky, Rosecrans performed well in the Deep South, scoring timely victories at Iuka and Corinth, Mississippi. When Buell was sacked, Rosecrans was the logical choice to succeed him.

Rosecrans received his appointment on October 24 and went right to work. Fearing a Confederate thrust toward the Tennessee capital, Rosecrans directed his troops, redesignated the Army of the Cumberland, into Nashville on November 7. He quickly whipped his command into shape, restoring discipline in the ranks and cashiering substandard officers. His personal command style was unique. A fervently devout Roman Catholic, Rosecrans was cool under fire but also subject to fits of frenetic overactivity. Despite his eccentricities, he was resoundingly popular with the troops. A skilled organizer, Rosecrans worked tirelessly to see that his men were always properly supplied and well fed. They responded accordingly. Rosecrans’s appointment, claimed Robert Stewart of the 15th Ohio, occasioned “silent rejoicing everywhere.”

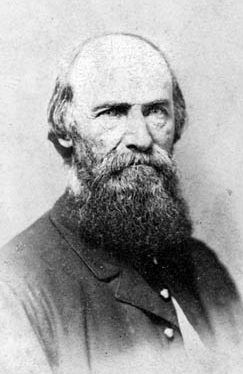

The same could not be said for Rosecrans’s opposite number. The commander of the newly christened Army of Tennessee, General Braxton Bragg, was arguably the most reviled general officer in the Confederacy—and not without reason. Although his personal bravery and dedication to the cause were not in question, Bragg’s notoriously contentious personality followed him wherever he went. The acerbic Bragg had turned personal vendettas into something of a cottage industry, engaging in a series of bitter feuds with nearly every senior officer under his command. The imbroglios had ramped up during the 1862 Kentucky campaign, when a number of his chief lieutenants called for his ouster. Bragg kept his job thanks to the good offices of President Jefferson Davis, a longtime friend, but his continued leadership ensured that the Army of Tennessee would remain crippled by dissension.

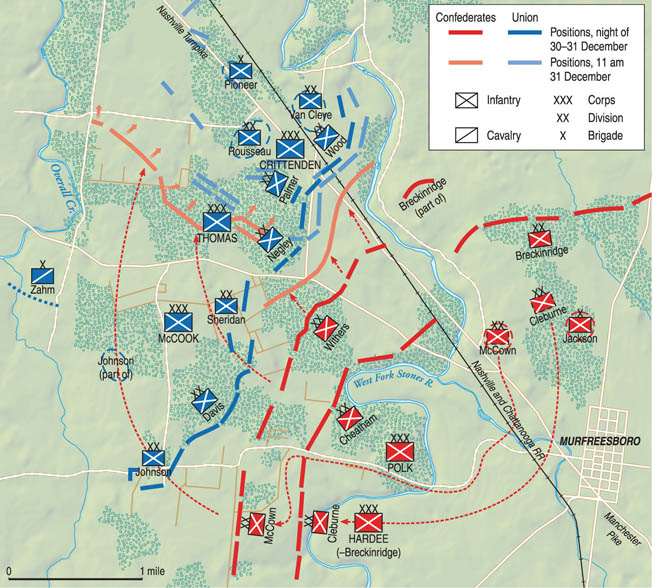

On the front lines in middle Tennessee, such a lack of cohesion courted disaster. Rosecrans, incessantly hectored by the War Department to mount an offensive, got his men in motion on December 26. The troops, advancing in a wide arc as they marched southeast from Nashville, were on a collision course with the Army of Tennessee. Rosecrans’s army, roughly 41,000 strong, was divided into three wings. The left wing was led by Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, a Mexican War veteran, Kentucky grandee, and solidly mediocre political general. The right wing was under the command of the affable McCook, who recently had proved so unlucky, or inept, at Perryville. Rosecrans’s center was led by stolid Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas. Although lacking the charismatic élan of many of his contemporaries, Thomas was a reliable career officer. Bearing the not entirely affectionate sobriquets “Old Slow Trot” and “Pap,” he was by no means a flamboyant leader, but his laconic composure had a steadying influence on troops under fire.

They would soon be in desperate need of such leadership. As Rosecrans advanced over the road network southeast of Nashville, the importance of one thoroughfare, the Nashville Pike, became increasingly apparent. The macadamized road was the most direct route toward the enemy and largely paralleled the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, a vital supply artery for any potential Union thrust toward Chattanooga. All major roads, as well as the rail line, converged at the town of Murfreesboro, a middling-sized commercial center situated near a shallow, meandering waterway, Stones River.

Planning For Battle at Murfreesboro

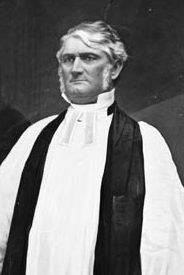

As the advance units of the two armies sparred and skirmished, a major confrontation in the vicinity of Murfreesboro became all but inevitable. By the evening of December 27, Bragg had concentrated the bulk his army at the town, divided into two corps. On the right was the corps led by Lt. Gen. William Hardee. A career officer and author of a widely used tactics manual, Hardee initially had enjoyed good relations with Bragg, but their relationship was souring rapidly. On Bragg’s left was the corps commanded by Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, a seemingly competent West Pointer who had opted for the Episcopal ministry and was serving at the outbreak of the war as the Bishop of Louisiana. Despite the pacific nature of his profession, Polk’s disagreements with Bragg had degenerated into a bitter personal feud.

Such squabbling didn’t bode well with a major fight in the offing. By December 30, both armies had moved into position northwest of Murfreesboro; a good portion of Confederate forces were deployed west of Stones River. Hardee, who considered himself an expert on such matters, was exasperated by the dispositions. Stones River, he warned, could be easily forded by an enemy flanking party, and the rugged ground west of the river was decidedly unsuitable for maneuvering large bodies of infantry. “The open fields beyond town are fringed with dense cedar brakes,” wrote Hardee, “offering excellent shelter for approaching infantry, and are almost impervious to artillery.”

The forbidding nature of the ground failed to dissuade either army commander. For his part, Rosecrans drafted an ambitious battle plan. He expected to receive an attack on McCook’s right wing and directed the Ohioan to simply tie up Confederate forces in the coming action. “Take a strong position,” ordered Rosecrans, “if the enemy attacks you, fall back slowly, refusing your right, contesting the ground inch by inch.” While McCook maintained his ground, Crittenden was to make the primary effort. Supported by Thomas, Crittenden was to cross Stones River, assail the Confederate right, and drive hard for Murfreesboro in the enemy’s rear. If all went well, asserted a confident Rosecrans, the Rebel line of retreat would be seized, “probably destroying their army.”

The Confederates were unlikely to simply await such a development. Coincidentally, Bragg had outlined a remarkably similar plan, intending to implement a grand turning movement against Rosecrans’s right. The prickly commander planned to execute a devastating right wheel into Rosecrans’s flank and roll up the Federal line en echelon from left to right, driving the enemy into Stones River and seizing the Nashville Pike, Rosecrans’s only viable avenue of retreat and resupply.

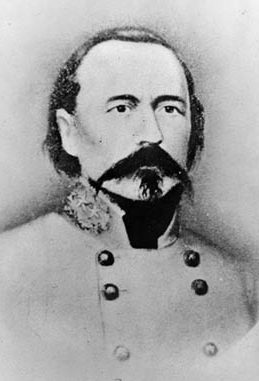

Bragg’s selection of the attack’s spearhead was a curious one. The lead division was that of Maj. Gen. John McCown, an officer whom Bragg held in little esteem; the Tennessean, in Bragg’s opinion, lacked the requisite capacity and nerve for weighty assignments. McCown’s supporting division, led by Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne, was in better hands. Cleburne, an Irish immigrant and British Army veteran, had started the war as a private soldier but earned his general’s stars in short order. Wielding a keen intellect, Cleburne had likewise proved himself a fierce fighter who kept a cool head in action.

Union Troops Surprised

By dawn on New Year’s Eve, Federal troops went about their morning routine with misplaced nonchalance. Rations were cooked, coffee was boiled, and arms remained stacked. The enlisted men were largely in the dark regarding the tactical situation, and most of their officers were equally detached. On the far right, Brig. Gen. August Willich was sanguine that the Confederates posed no serious threat in his sector. “They are so quiet out there,” he remarked to a fellow officer, “that I guess they are all no more here.”

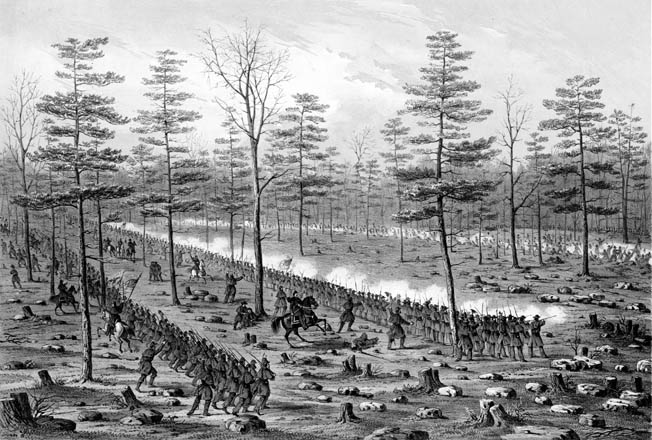

At 6:30 am such illusions were shattered. Federal pickets could hardly believe their eyes. Out of the morning mist stepped a fearsome line of Rebel infantry, advancing in ominous silence. The attack was spearheaded by McCown, arrayed in a three-brigade front that easily overlapped the Federal right; Cleburne followed 500 yards behind. The center of McCown’s line was held by Brig. Gen. Mathew Ector’s brigade, a tough outfit largely composed of dismounted Texas cavalry. Northern batteries frantically opened up on the Confederates but failed to halt their progress. Federal Brig. Gen. Edward Kirk, in a desperate bid to buy time, ordered his 34th Illinois to attack the Rebels. The Illinoisans went forward gamely but were quickly brushed aside, leaving the exposed Federal position wide open.

There was little time for startled Union troops to react. Coming on at the double quick and howling like Indians, the Texans tore into the Federal line. Kirk’s brigade, which bore the brunt of the initial onslaught, fought briefly and then disintegrated. Kirk was carried from the field with a shattered hip. Although the Confederates had run a gauntlet of artillery fire, the contest with Kirk’s infantry was over almost as soon as it began. The assault was “like a storm taking them completely by surprise,” recalled a delighted Captain John Lavender of the 4th Arkansas. “Their coffee pots was on the fire frying their meal, guns in stacks.”

With Kirk scattered, the full weight of the Confederate juggernaut fell on Willich’s brigade. Cut off from the rest of the division, Willich’s hapless troops took the weight of Ector’s brigade full in the flank. Isolated groups of Federal troops put up a hopeless fight, but most fled in complete disorder. They had, sometimes literally, been caught with their pants down. A lieutenant in the 14th Texas recallied that “many of the Yanks were either killed or retreated in their night clothes.” Hundreds were taken prisoner during the chaotic rout, including Willich, who was snatched up by exuberant Texans.

In little more than 30 minutes of whirlwind fighting, the two brigades occupying Rosecrans’s right flank had been nearly obliterated. McCown’s troops, exhilarated that the enemy had crumbled so quickly, veered off to the west, hot on the heels of fleeing Yankees. The three brigades maintained good order but were badly out of position. Cleburne, bringing up his supporting division, ran into fresh Federal troops and was perplexed that McCown had seemingly disappeared from his front. Unfazed by the mix-up, Cleburne filled the gap with his own troops and pressed on.

Liddell’s Advance in the Open

Cleburne had run into the Federal division of Jefferson C. Davis, a scrappy Hoosier brigadier who, much to the amusement of his own men, shared his name with the Rebel president. Davis had time to adjust his troops, realigning Colonel P. Sidney Post’s brigade to face the Confederate onslaught. In Post’s right rear was a reserve brigade under the command of Colonel Philemon Baldwin, who had his troops take what cover they could behind a cornfield and rail fence. Both brigades counted on support from the ever-efficient Federal batteries.

Confederate officers could clearly discern that the Union position would not be a pushover. The Arkansas brigades of Brig. Gens. Evander McNair and St. John Liddell became snarled during the advance, and the two brigadiers halted the attack while they bickered about how best to hit Baldwin. McCown had to personally sort the matter out, eventually ordering both brigades forward in unison. Liddell, a West Point dropout, was a good choice for a tough job. A sensible combat commander, Liddell was respected by his men and brave to a fault.

Hat in hand, he personally led them forward. Liddell’s Arkansans advanced in the open and paid a grim price. Enemy artillery and small arms swept his ranks, and Liddell, apprehensive that his troops would be slaughtered if they pressed forward unsupported, halted the brigade. The deadlock was broken when a tardy McNair finally brought his brigade into the fight. Sweeping forward at a run, the Arkansans wrecked an impromptu force that Federal officers had patched together on Baldwin’s right. McNair then swung his brigade toward Baldwin’s main force, which cracked under the pressure. The Federals fell back reluctantly, the commander of the 1st Ohio resorting to blistering profanity to get his Buckeyes to retreat. Liddell’s troops, who had been roughly handled during the exchange of gunfire, plunged forward and succeeded in dislodging the Union troops.

Post’s brigade, which sat astride the Gresham Lane, fared little better. Soon after Post had his men in position, Confederate troops surged toward his front. It was Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s Tennessee brigade that advanced across open ground and suffered badly for it. Post’s infantry unleashed a hail of musketry, and they were further supported by Captain Oscar Pinney’s four guns of the 5th Wisconsin Artillery. Pinney, who had been anxiously awaiting the opportunity to get into action, did grim work. Tearing great gaps in their ranks, Pinney’s accurate fire left the Tennesseans stalled in the open. Rebel artillery soon struck back. Unlimbering behind the beleaguered infantry, Captain Putnam Darden’s Jefferson Flying Artillery subjected Pinney’s guns to intense counterbattery fire. Pinney was forced to draw off his guns. With the Union artillery in full retreat, Johnson’s brigade charged forward and broke Post’s right, unhinging the entire brigade line.

“Everything Was Perfect Confusion”

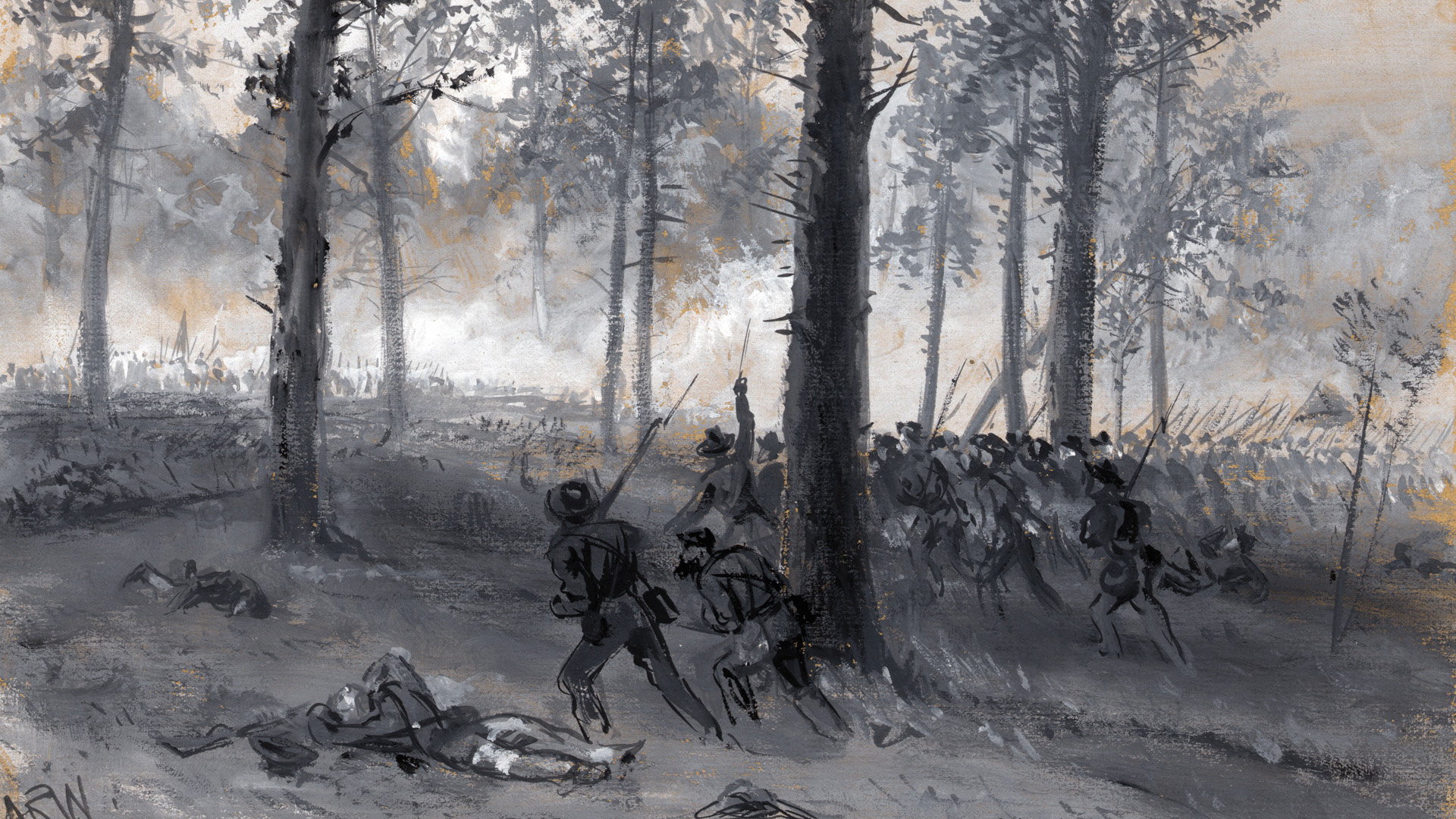

The next Federal brigade in line, commanded by Colonel William P. Carlin, was strongly positioned to receive an attack. Carlin, a stern professional soldier with a reputation as a tough fighter, had his men situated among boulders in a thick stand of cedars east of the Gresham Lane. The cedar thicket offered poor visibility, and the onrushing Confederates had no idea that he was waiting for them. They were, at least, coming on in strength—two brigades under the command of Brig. Gens. S.A.M. Wood and Lucius Polk, nephew of the fighting bishop. Like Cleburne, neither brigade commander was aware that McCown had careened off course. Polk’s troops unexpectedly came under fire, while Wood’s oblivious Butternuts stumbled into a deadly trap. From near point-blank range, the Confederates took a devastating volley from the concealed ranks of the 101st Ohio. Staggered by the ambush, Wood pulled back.

Carlin drew in his right flank in anticipation of a renewed Confederate thrust, but the numbers were against him. Wood and Polk threw their combined weight at his line and Carlin ordered a withdrawal in the face of the deadly pincers. The Federals were subjected to withering crossfire; Carlin himself was wounded as his men scrambled for the rear. “Everything was perfect confusion,” recalled Jay Butler of the 101st Ohio, “men and horses running in every direction and Rebels after us, firing upon us and yelling like Indians.”

Sheridan’s Tough Defense

Despite their initial success in shattering the Federal right, Confederate troops soon ran into mounting difficulty as the fighting expanded. As the attack shifted north, the battle came increasingly under Polk’s direction. Although the bishop was a West Point graduate, he was better equipped for the pulpit than the battlefield. He had thrown his wing into disarray the previous day after instituting a muddled reorganization and now committed his formidable command in piecemeal fashion. Polk’s lead division commander, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, didn’t help matters. A barrel-chested bull of a man, Cheatham was a tough fighter whose undeniable bravery was sadly compromised by excessive fondness for the bottle. Subsequent to the battle at Stones River, the general would be dogged by persistent rumors that he had been pitifully inebriated during the fighting.

The most nagging problem for Confederate troops proved to be Union General Sheridan. The scrappy little Irishman had remained edgy since the previous evening, and he had ordered his division under arms well before dawn. Far from being caught unawares, his troops, largely Midwestern volunteers, were ready and waiting for the enemy, and Sheridan had also bolstered his line with artillery. The right flank brigade, led by Joshua Sill, was formed on a ridgeline crowned with heavy timber. Sheridan and Sill were among the few Federal generals who had actively prepared for the Confederate attack. Paired together in the face of impending crisis, they would prove a formidable duo.

The grim task of assaulting Sheridan’s position fell to the brigade led by Colonel J.Q. Loomis, who brought his troops forward roughly an hour behind schedule. Loomis’s men, largely Alabamians, were forced to brave a 300-yard expanse of open ground and were badly cut up in the process. When they neared the wood line, panicked Federal troops from Colonel William Woodruff’s brigade fled into the timber on Loomis’s left. The 26th Alabama impetuously surged into the gap but left their own flank dangerously exposed in the process. The troops of the 35th Illinois unleashed a deadly enfilade fire into the Alabamians, abruptly scattering them to the rear.

Loomis’s center regiment, the 1st Louisiana, was fortunate to face the 24th Wisconsin, a fresh regiment of greenhorns that broke in short order. But on the Confederate right the two opposing lines viciously mauled each other in a stand-up fight that lasted half an hour. Both sides took a heavy beating and the Rebels, in the open and subject to artillery fire, were the first to crack. When they fled to the rear, the Federals counterattacked and cleared the Rebels from the field to their front.

It had been a short but ghastly fight, and two brigade commanders were already out of action. Loomis was injured when artillery fire sent a tree limb crashing on top of him; Sill, who had ridden up and down the line encouraging his troops, was felled when a Minie bullet fatally struck him in the mouth and exited the back of his head. His aide, Lieutenant John Mitchell, found the stricken brigadier “unconscious and alone, bubbling out his last breaths through blood that thickly flowed over his fair face.”

Attacked by Fresh Confederates

The Federals had little time to rest. Within minutes, a fresh line of Confederates appeared in the distance, the reserve brigade of Colonel Alfred Vaughan. Vaughan’s troops had jeered the Alabamians for retreating, and one winded soldier had angrily pointed to the Yankees and barked, “Yes, and you’ll find it the hottest place that you ever struck.”

Vaughan’s men were indeed in for a rude awakening. His troops muscled aside Woodruff’s Federals but were quickly driven off by a counterattack. Only the hard-driving 9th Texas, oblivious that the rest of the brigade had fallen back, pressed forward. The regiment’s leader, Colonel William Young, repeatedly ordered his men forward to engage the 35th Illinois but quickly found that he had led his men into a deadly crossfire. Trapped between the 35th and 38th Illinois, Young scorned the notion of falling back. Dramatically lifting the regimental colors, Young ordered a fresh charge directly into the 35th Illinois. His desperate gamble paid off, the Illinoisans broke, and Woodruff’s line came unhinged.

Sill’s former outfit was likewise the target of a fresh Confederate brigade, that of Colonel Arthur Manigault. The South Carolinian led his troops into the same firestorm that had chewed up Loomis. Advancing without support, the Confederates were sent reeling back across the field. Despite his division’s admirable performance in the face of repeated attacks, Sheridan nonetheless deemed it high time to pull the troops back to better ground. His men were running low on ammunition; worse yet, it was obvious that the Rebels were regrouping for a concerted push for the Wilkinson Pike.

Sheridan narrowly extricated his division before the blow struck. Desperate to get his troops back to better defensible ground, Sheridan ordered Colonel George Roberts’s brigade to mount a counterattack into the advancing Confederates. Roberts, who defiantly exposed himself in front of his own line, histrionically appealed for his men to rely on cold steel. “Don’t fire a shot!” he shouted. “Drive them with the bayonet!” His brigade tore into Manigault’s brigade and gave Sheridan a brief but much-needed breathing spell

“The Ground Was Literally Covered With Blue Coats Dead”

Along the Nashville Pike, Rosecrans was painfully slow to comprehend the magnitude of the looming disaster. Prior to launching his own attack earlier that morning, the general had, as was customary, heard Mass along with his friend and chief of staff, Lt. Col. Julius P. Garesché. He then optimistically sent two of Crittenden’s divisions across Stones River in execution of his planned attack on Bragg’s right. Due to a lack of clear information, Rosecrans remained blissfully unaware that his right had caved in. After receiving the first vague reports from the right wing, Rosecrans remained confident that everything was proceeding as planned. “It is working right,” he announced to his staff. If McCook could maintain his ground, “we will swing into Murfreesboro and cut them off.”

Such an assessment was utterly disconnected from reality, a fact that became increasingly apparent. When Rosecrans received word that Willich’s brigade had been obliterated, he sprang to action with characteristic energy, immediately ordering one of Thomas’s divisions under the command of Maj. Gen. Lovell Rousseau to shore up the line on Sheridan’s right. At the same, he called back the two divisions he had sent across Stones River. Far from assuming the offensive, Rosecrans was locked in a desperate defensive battle that threatened the destruction of his entire army.

As the battle raged unabated on the right, Federal officers enjoyed mixed success as they frantically attempted to rally their broken and disordered commands. The tangled cedar thickets and farm fields south of the Wilkinson Pike were the scene of a bloody running fight that took a horrific toll of life. “I cannot remember ever seeing more dead men and horses and captured cannon, all jumbled together,” recalled Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee. “The ground was literally covered with blue coats dead.” While Manigault regrouped his disordered brigade, he found help in the form of Brig. Gen. George Maney’s Tennesseans. Manigault’s men had been taking a beating from two Federal batteries, those of Captains Charles Houghtalling and Asahel Bush, that had the South Carolina troops trapped in a deadly crossfire.

The two brigadiers agreed to launch their troops at the batteries in unison, Maney at Bush and Manigault at Houghtalling. Bush’s battery fled before Maney could close on the position, and the Tennessean assumed that Manigault had already seized Houghtalling’s guns as well. The South Carolinian, however, was nowhere to be found. When Maney’s luckless troops approached Houghtalling’s battery, which they unaccountably assumed to be friendly, they were greeted by a murderous salvo that disabused them of the notion. While Houghtalling’s Illinoisans banged away at every Rebel in sight, bewildered Confederate officers dickered over the identity of the gunners and what to do about them.

Sherman’s Men in the Slaughter Pen

As the Confederate attack proceeded in costly fits and starts, Sheridan was granted precious time in organizing a hasty defense of the most forbidding terrain on the field. While maintaining contact with Brig. Gen. James Negley’s division on his left, Sheridan bent back his right until his position assumed the shape of a large “V.” It was a precarious salient that pointed far to the south, but it was situated in a boulder-strewn cedar forest so dense that it constituted ready-made breastworks.

When Manigault’s brigade at last lurched forward, the general directed his troops at the formidable concentration of Federal guns at the apex of Sheridan’s hairpin defensive line. For the men who grappled there, it was a terrifying experience. The crouching soldiers of the 42nd Illinois that awaited the Rebels could see next to nothing. The cedars were so dense, recalled one survivor, that they were not aware of the approach of the enemy until they saw their glistening bayonets a few feet from them. In a few paralyzing moments, the forest floor erupted with flashes of musketry. Men dropped by the dozen as the two sides savagely mauled each other. The Alabamians, dazed by the punishment, fell back.

What ensued was one of the most savage and sustained actions of the war. As advancing Confederate troops curled around the Union salient, they unleashed repeated assaults at the Federal position. Fortunately for the defenders, the disjointed attacks were considerably blunted due to lack of coordination. Exhausted and mystified Confederate officers led their troops into a bewildering maze of tangled cedar thickets and limestone outcroppings. The forest was rapidly blanketed in choking clouds of smoke, and opposing lines routinely stumbled into each other at close quarters. The carnage was immense. Lt. Col. Junius Scales, who led his 30th Mississippi into the brutal maelstrom, later recalled that “every foot of soil over which we passed seemed dyed with the life blood of someone.”

Both sides fought with bitter tenacity. Wave after wave of Confederate troops clashed against the forest with little effect. Rosecrans, who was desperately organizing a last-ditch defense of the Nashville Turnpike, ordered Sheridan to buy time for the rest of the army by holding his position at all extremities. His troops did just that. Caught in the closing jaws of a Confederate assault that swept in from the west, south, and east, the Federals were subjected to a horrendous crossfire made worse by Rebel artillery. Confederate commanders had rolled up every available gun to hammer away at the Yankees, sending a storm of shells crashing through the forest. Trees splintered and cowering soldiers were torn to pieces by sharp wooden projectiles ricocheting among the boulders.

For more than an hour the battered Union troops held their position, but eventually they began to run low on ammunition. Sensing the inevitable, Sheridan reluctantly ordered a retreat. The Federals came to rue the impressive rock formations that had served as such inviting defensive positions. As they scrambled over the boulders, they fell prey to Confederate formations that closed in for the kill. Few of the Federal artillery pieces could be extricated from the deadly trap; the boulder-laced cedar thickets, explained Sheridan, were “almost impenetrable for wheeled carriages.” The veterans who struggled in the confounding labyrinth of cedar trees were witness to horrors that they would never forget. “The history of the combat in those dark cedar thickets,” recalled a soldier of the 36th Illinois, “will never be known.”

For the exhausted Illinoisans who fled for the rear, the scene conjured up gruesome images of the Chicago stockyards; they christened the ground the Slaughter Pen. Sheridan’s beleaguered division had been decimated, but their resolute defense of the army’s dangerously exposed flank had afforded Rosecrans priceless time to patch together a new defensive line along the Nashville Pike.

“Until Hell Freezes Over”

The unexpected ferocity of the Confederate attack had wrecked McCook’s wing, and thousands of troops fled for the rear in complete chaos. “Fugitives and stragglers emerged from the cedars in full view,” recalled Lieutenant John Yaryan, “followed by confused masses of panic-stricken troops.” Rosecrans himself was anything but composed, becoming nearly hysterical as he worked frantically to save the army and his own reputation. The general grasped at every available reserve to stabilize his collapsed right flank.

Off to Sheridan’s right, Rousseau directed his division into the dense cedar thickets south of the Nashville Pike. They plugged the gap none too soon. Subsequent to the morning’s confusion, McCown had reorganized his battered division and pushed hard for the Union rear. Rousseau’s troops tangled with the Confederates briefly and then fell back to the safety of supporting artillery along the pike. In the confusion, Colonel John Beatty’s brigade never got the word to retire. A solid combat leader, Beatty had received orders to hold his position “until hell freezes over,” and he endeavored to do just that.

Beatty’s Midwesterners hastily threw together ad hoc breastworks of tree limbs and settled in for a fight. Lucius Polk led his brigade against the stronghold and was roughly handled in the process. After receiving withering fire during a failed frontal attack, Polk attempted to edge past Beatty’s right, but abruptly ran into the concealed ranks of the 15th Kentucky. The Bluegrass Unionists fired an unexpected volley into the Rebels that sent them reeling. Beatty had belatedly wised up. After repeated attempts to make contact with adjacent units, he came to the conclusion that his brigade had been abandoned. The annoyed colonel pulled his men out and sardonically explained that “the contingency to which General Rousseau referred—that is to say, that hell had frozen over”—had indeed taken place.

Beatty’s attempts to rally his brigade failed until he reached the turnpike. McCown’s brigades then mopped up the last Federal resistance in the cedars, pressed toward the pike, and halted at the edge of the forest. Lines were dressed before renewing the assault. Once again the rugged terrain, paired with the inevitable fog of war, ensured that the Confederate thrust for the Nashville Pike would result in uncoordinated butchery.

Collapse of the Confederate Attack

Ector, whose hard-fighting Texans had enjoyed such success earlier in the morning, went forward unsupported across open ground. Waiting for the veteran Texans were green Union troops. In his desperation to fill gaps along the Nashville Pike, Rosecrans had ordered up Brig. Gen. John Morton’s Pioneer Brigade, an engineering outfit expected to see little action. The Pioneers were supported by Battery B, Pennsylvania Light Artillery, and Captain James Stokes’s Chicago Board of Trade Battery. Raised and equipped by patriotic Chicago commodities traders, the men of the battery had yet to see a serious fight.

The Texans streamed across the open ground but soon found themselves in a tight spot. Slugging it out with the Pioneer Brigade, Ector’s right, lashed by artillery fire, took the worst of it. The Texans’ left fared even worse. Their flank was unprotected by supporting units, and Colonel Samuel Beatty’s Union brigade pitched into their left. The bitter struggle ultimately left the Federals master of the field after Ector, reluctantly, pulled his men out.

Beatty, along with Colonel James Fyffe’s brigade, followed close on the heels of the routed Texans but ran into unexpected resistance of their own when they neared the cedars. It was Cleburne’s division, stretching far beyond the Federal flank. The doughty Arkansan wasted little time in throwing his men at the overextended Yankees. Faced with overwhelming pressure, Colonel Charles Harker pulled his Federal brigade back to protected ground far off Fyffe’s right. For Fyffe and Beatty, the move was a disaster. Swiftly edging past Fyffe, Cleburne’s veterans tore into the exposed Federal flank and unhinged the two brigades. Panic-stricken Yankees fled in confusion, and Cleburne’s entire division headed for the final prize—possession of the Nashville Pike.

In the face of looming catastrophe, Rosecrans scooped up every available regiment and threw them into line. In what the pious general could only have regarded as a miracle, the threat inexplicably evaporated. As astonished Confederate brigadiers watched in amazement, their vaunted regiments broke and fled for the rear in considerable confusion. Liddell, for his part, was outraged by the sudden collapse of the Confederate attack. “The movement was totally unexpected,” reported the Louisianan, “and I have yet to learn that there exists a cause commensurate with the demoralization that ensued.” Cleburne was more sympathetic to the plight of his weary foot soldiers. Running low on ammunition and unsupported by artillery, Cleburne noted that his men “had little or no rest the night before; they had been fighting since dawn, without relief, food, or water.” Quite simply, they had reached the limits of human endurance.

“Mississippi Half Acre”

Bragg was nonetheless determined to break the enemy once and for all. Rather than redouble his efforts against the shattered Federal left, Bragg focused his energies on the right, where, he thought, Rosecrans’s remaining flank was invitingly situated for a crushing blow. The prickly army chief was hopeful that a final drive against the weakened Federal left would achieve a decisive breakthrough, seize the Nashville Pike, and occasion the complete disintegration of the Army of the Cumberland. Bragg, however, would face fierce resistance in the form of a particularly stubborn Federal brigade under the command of Colonel William B. Hazen.

A hard-bitten Old Army man, Hazen had graduated in the West Point Class of 1855 and cut his teeth fighting Comanche on the southern plains. Badly wounded during a fight in 1859, Hazen was back in the field as an Ohio colonel at the outbreak of the war. He was also one of the toughest brigade commanders in Crittenden’s left wing. Hazen’s four regiments, the 41st Ohio, 9th Indiana, 6th Kentucky, and 110th Illinois, were positioned across the Nashville Pike and would defy the Army of Tennessee for the better part of a day. They were drawn up in a conspicuous stand of timber that would forever be remembered as the scene of unspeakable carnage—the Round Forest.

Troops positioned in the vicinity of the Round Forest had sparred with the Confederates since daybreak, but their first major challenge came from Brig. Gen. James Chalmers’s Mississippi brigade. Not untypical for Confederate attacks that day, Chalmers’s troops came forward unsupported. Adding insult to injury, the 44th Mississippi on Chalmers’s right went into action woefully underequipped; many of the troops were armed with what one staff officer described as nearly inoperable “refuse guns.” A number of unlucky soldiers carried no arms at all. Nevertheless, the indomitable Mississippians improvised and went forward with wooden staffs at shoulder arms. It was a recipe for disaster.

As the brigade angled its way forward, it divided when it reached the Cowan Farm southeast of the Round Forest. Chalmers personally led the bulk of his men to the left of the farm, while two of his regiments veered north. Both detachments stumbled into a maelstrom. Chalmers and his men slugged it out with the Federals from a distance of 50 yards. The unforgiving exchange of musketry resulted in ghastly and pointless carnage. While the defenders of the Round Forest remained unmoved, Chalmers’s brigade was torn to pieces. So many of the Rebels littered the ground that the scene was remembered as the “Mississippi Half Acre.”

“Men Were Falling Along the Line”

The attacks continued unabated. Brig. Gen. Daniel Donelson led his fresh brigade of Tennesseans in Chalmers’s wake and executed a bloody reprise of the earlier attack. His command likewise split when it reached the Cowan Farm, and Donelson veered to the west of the Round Forest. The Federals couldn’t help but watch the grand attack with admiration. The Rebels came on in crisp ranks, thought Brig. Gen. John Palmer, and “it was not easy to witness that magnificent array of Americans without emotion.”

Donelson would have help. Brig. Gen. Alexander Stewart’s Tennessee outfit came into action on his left, driving back the Federals under the command of Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft. General Thomas was quick to react. Close at hand was a crack brigade of U.S. Army regulars under the command of Oliver Shepherd, still a lieutenant colonel after two decades of service. Directing Shepherd to the dark cedar forest south of the Nashville Pike, Thomas gave simple orders. “Shepherd,” he said, “take your men in there and stop the Rebels.”

The regulars faced a harrowing crucible. In an unforgiving toe-to-toe fight, the two lines repeatedly unleashed shuddering volleys into each other; both sides stubbornly refused to yield an inch. “Men were falling all along the line,” recalled an admiring Federal staff officer, “but not one turned his back to the enemy.” Ultimately, cool discipline triumphed. The regulars succeeded in shattering Stewart’s advance but paid a heavy price for it. After the smoke cleared, 400 regulars lay dead or wounded on the forest floor.

When Stewart’s and Donelson’s battered brigades fled the field, it was growing increasingly clear that Confederate troops were unlikely to wrest the Round Forest from Rosecrans, who had shifted so many spare regiments to the threatened sector that the area was now the most heavily manned section of the battlefield. Bragg, however, remained as committed as ever to seizing the Round Forest, and the attack stubbornly continued, one brigade at a time, constituting a truly senseless loss of life.

“Brave Men Die in Battles”

The next Confederate unit haphazardly thrown into the meat grinder was Brig. Gen. Daniel Adams’s outfit. Advancing directly astride the Nashville Pike into the teeth of Hazen’s fortress, Adams’s troops were badly torn by Federal artillery and small arms as they pressed the futile attack. Their advance stymied by the persistently troublesome impediment of the Cowan Farm, Adams’s troops approached the Round Forest badly deprived of momentum. Sensing an opportunity, Colonel George Wagner unleashed the 15th and 51st Indiana in an unexpected bayonet charge. Taken aback by the Hoosiers, Adams ordered a retreat.

Polk, however, was far from finished, but unfortunately for the common soldiers destined to do the actual fighting and dying, the high command had clearly run out of fresh tactical ideas. The bishop launched a further series of attacks toward the Round Forest that were clearly doomed to failure and executed with little enthusiasm. Three more brigades, those of John Jackson, John Palmer, and William Preston, accomplished little more in their 11th-hour assaults than to add to the carpet of dead and dying men in front of the Round Forest.

Rosecrans himself narrowly avoided death toward the close of the action. While riding at the head of a group of officers, a Confederate projectile flashed by the general and struck his close friend Julius Garesché. The shell carried away Garesché’s head, and his horse plunged another 50 yards before the officer’s body fell to the ground. Rosecrans kept his composure through the macabre incident and tersely expressed his view of a soldier’s lot. “Brave men,” he remarked, “die in battles.”

20,000 Men Killed

It was a stark assessment that could just as easily apply to the thousands of men who were killed or maimed during the opening day’s fighting at Stones River. As darkness fell, the troops in both armies instinctively collapsed after enduring 10 solid hours of grueling combat. During the course of the daylong struggle, the two opposing armies had brutalized each other in some of the worst fighting in American history. The once pastoral fields and forests outside of Murfreesboro had been transformed into a bloody shambles littered with human wreckage. In all, approximately 20,000 men were left killed, wounded, or missing during the deadly struggle west of Stones River.

The nightmarish ordeal left searing memories. Some of the dead, remembered William Newlin of the 73rd Illinois, appeared to be sleeping, “eyes closed, hands at their sides, and countenances unruffled. Others appeared as if their last moments had been spent in extreme pain—eyes open, and apparently ready to jump from their sockets; hands grasping some portion of their garments and their features all distorted and changed. It was a sickening sight to look upon.”

The unspeakable bloodletting failed to dissuade Bragg from maintaining the fight. His troops had wrecked a good portion of the Army of the Cumberland, battered in the Federal right for about three miles, and come tantalizingly close to ultimate victory on the Nashville Pike. All in all, it seemed to have been a promising start. “We assailed the enemy at seven o’clock this morning,” the general reported, and “have driven him from every position except the extreme left. With the exception of this point we occupy the whole field.” Bragg decided to sit tight and await developments, convinced that daylight would find the Army of the Cumberland in full retreat.

In that belief he would be sorely disappointed. In the candlelit confines of his headquarters cabin, Rosecrans assembled his army’s senior officers for a momentous council of war. No one would readily admit suggesting retreat, but the possibility was discussed at length. Thomas and Crittenden were for giving battle again. Although McCook’s wing had clearly taken a severe thrashing, the troops had fought remarkably well and exacted a steep price from the Confederates. More importantly, the lines had stabilized and battle-weary soldiers, justifiably anxious for a little cover on the morrow, were working feverishly to throw up breastworks.

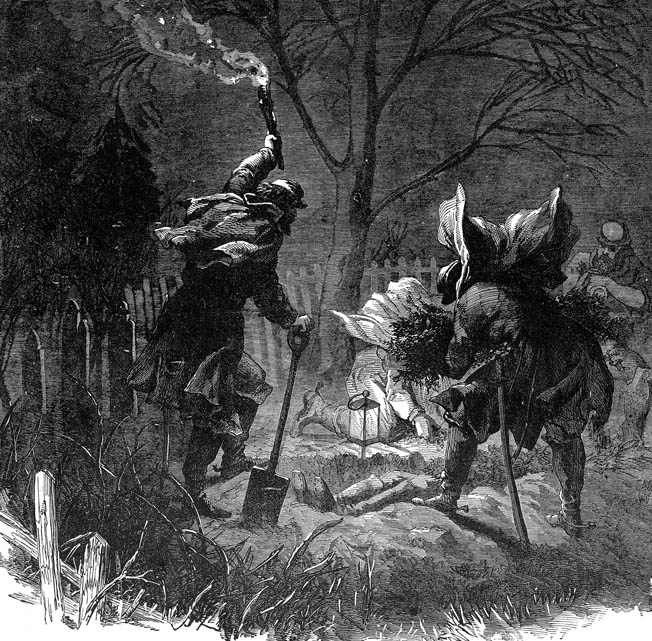

Before he made his decision, Rosecrans, accompanied by McCook, rode east along the pike. McCook later explained that Rosecrans was looking for defensive positions to which he could fall back. Nearing Overall Creek, the general spotted torches in the distance. They were carried by his own cavalry, but in the darkness he was convinced that Confederates were preparing for a dawn assault. Returning to headquarters, Rosecrans explained that the enemy had gotten “entirely in our rear and are forming a line of battle by torchlight.” The Army of the Cumberland, he announced, had little choice but “to fight or die.” By the closing hours of December 31, it was unclear which of those options was the most likely to occur.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments