By William F. Floyd, Jr.

The blue-coated soldiers trudged uphill through the forest trying their best not to get snagged on the laurel branches or stumble over the tree roots. At the head of the column was a David Hart, a handsome 22-year-old guide whose father owned a farm at the summit of the mountain. The five-mile trek, which was supposed to take just three hours, had begun at dawn and dragged on into the afternoon. Just as the march started, the heavens opened up and a hard rain fell on the untried troops. They received some protection from the mature trees that bent over the trail.

The Midwesterners in the column had been mustered into service a short time before. Their commander was 35-year-old, West Point Class of 1846 graduate Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. The general had assured President Abraham Lincoln and the members of the War Department in Washington that he would drive the “Secesh” in northwestern Virginia as far as Richmond if necessary. He was the hope and pride of the intensely loyal Unionists of the upper Ohio River Valley.

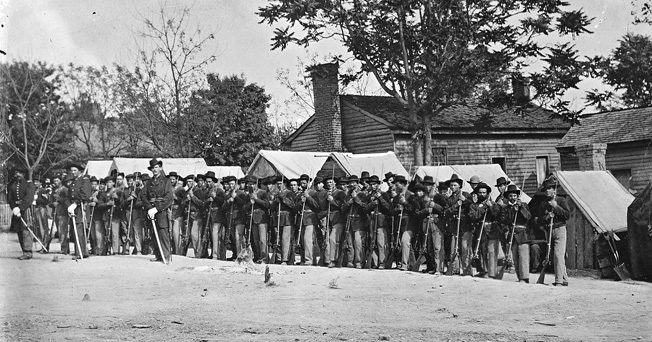

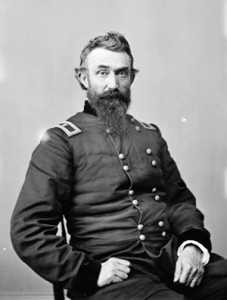

But the flanking column was not led by McClellan, who was at the Roaring Creek bivouac at the western base of Rich Mountain in northwestern Virginia with the bulk of his forces on July 11, 1861. Forty-one-year-old Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, West Point Class of 1842, led the column, which consisted of his brigade’s two Ohio and three Indiana regiments. Although he had two batteries, Rosecrans left all of his guns behind because his young guide had told him that the trail was too narrow and rough for limbered artillery. Rosecrans, with his high forehead, hooked beak, and solid six-foot frame was a man who meant business. The 1,900 Midwesterners who belonged to his brigade knew all too well that they had to toe the line or face his hair-trigger wrath.

At 11 am Rosecrans halted the column for a brief rest while he fired off a message to McClellan informing him that he had not yet reached his objective. A mounted messenger rode down the hill to deliver the update. The night before, the two generals had carefully planned their attack. Rosecrans would gain the enemy’s rear, and McClellan, when he heard heavy firing on the mountain, would launch a frontal attack against the Confederate bivouac that the Southerners called Camp Garnett. When Hart informed Rosecrans that they were getting close to his father’s farm, the general ordered Colonel Mahlon Manson to deploy skirmishers from his 10th Indiana Regiment. In a few minutes, the Union attack would commence. Disaster loomed for the Confederates on Rich Mountain.

The Battle of Rich Mountain was characteristic of the small battles that occurred as the Union and Confederate forces battled for control of northwestern Virginia in the first eight months of the war. The South was put on the defensive in the region early in the war as a result of the desire of the independent-minded mountain people to remain loyal to the Union. On April 17, 1861, the Virginia convention voted to secede from the Union. Delegates from the western counties of Virginia who had voted against secession stormed out of the convention. They held their own convention in Wheeling on June 11 at which they nullified the ordinance of secession and vowed to create a new state made up of the Old Dominion’s western counties.

George McClellan vs Robert E. Lee

The so-called West Virginia Campaign of 1861 pitted Maj. Gens. McClellan and Robert E. Lee against each other in an early test of their tactical and strategic skills. Idiosyncratic traits of each man’s personality would come to the fore during the campaign. For example, McClellan’s erroneous estimates of enemy forces and his penchant for letting his subordinates do the hard fighting were plainly visible. As for Lee, he strived for a diplomatic approach when confronted with the surly and uncooperative behavior of certain subordinate commanders when he should have dealt with them severely, if necessary charging them with neglect of duty. He also issued overly complex orders that called for multiple columns to converge on an objective. These complex plans proved too difficult for his subordinates to carry out.

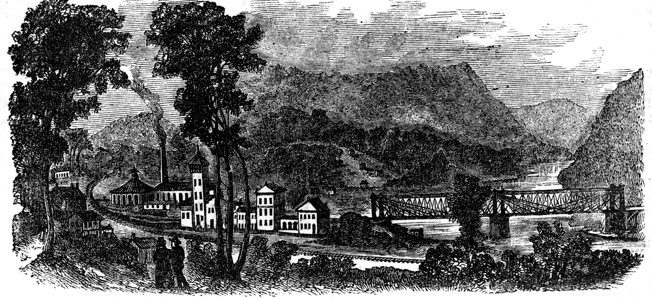

The high command of both the Union and Confederate Armies realized following the outbreak of war in April 1861 that they needed to hold the railroad town of Grafton if they were to control northwestern Virginia. Grafton is situated 120 miles west of Harpers Ferry. The town not only was a stop on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, but also the eastern end of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad to Parkersburg. For the Union, control of the B&O Railroad was essential to the movement of troops and supplies from the Ohio Valley to Baltimore and Washington. The Confederates wanted to sever the railroad, and Grafton was a good place to begin.

Throughout April McClellan drilled his Ohio recruits in preparation for an advance into Virginia. Lee, who was given command of Virginia’s forces on April 23 by Governor John Letcher, dispatched Colonel George Porterfield in early May to Grafton to recruit a local Confederate force. Porterfield was given command of the newly established Department of Northwestern Virginia. Upon his arrival, he found few troops loyal to the Old Dominion in the town.

Lee failed to appreciate the independent nature of many of the residents of western Virginia. They had little in common with the slave owners of the Tidewater and Piedmont sections of Virginia. Many were kindred souls with the pro-Union communities along the Ohio River. Lee discovered the hard way that if he wanted Porterfield to succeed he would have to send reinforcements from eastern Virginia.

The Federals Close in on Philippi

The Federals wasted no time raising troops to secure the B&O Railroad and push back Confederate forces in northwestern Virginia. Colonel Benjamin Kelley raised a U.S. regiment on Confederate soil in Wheeling. The pro-Northern recruits who flocked to the Stars and Stripes in northwestern Virginia were mustered into Kelley’s 1st Virginia Volunteers in Wheeling. General Winfield Scott cabled McClellan on May 24 instructing him to take prompt action in the field against Porterfield’s Rebels. McClellan, who was training new recruits in Cincinnati, ordered Kelley to seize control of Grafton. To assist Kelley, McClellan dispatched two regiments of Ohio volunteers and an Ohio artillery battery.

Union authorities hoped that the campaign in northwestern Virginia would help create a political environment that would allow the people of Trans-Allegheny Virginia to create a new state that would become a permanent part of the Union. Recognizing the nature of operations in an area where family loyalties were apt to be divided, McClellan issued a letter to the volunteers urging restraint against civilians. “Remember that your only foes are the armed traitors,” he wrote. Kelley marched out of Wheeling at the head of his regiment on May 27 bound for Grafton. By that time Porterfield had about 550 locals willing to fight for the Confederacy. Realizing that he would be heavily outnumbered with three regiments converging on his position, Porterfield retired 15 miles south to Philippi.

Philippi was located on a key north-south artery, the Beverly-Fairmont Road, which bypassed Grafton a short distance to the west. A splendid covered bridge carried the road across the Tygart River. The residents of Philippi were friendlier to the Confederates than those of Grafton. Awaiting Porterfield’s arrival were two companies of soldiers, an infantry company from Upshur County to the west and a cavalry company from Rockbridge County in the Shenandoah Valley. These men were armed with outdated flintlocks or flintlocks that had been converted to percussion cap muskets. They scavenged whatever lead items they could to melt into bullets and rolled homemade cartridges. Still, they only had about five cartridges per man. If he were to meet McClellan on equal terms, Porterfield would need more men and equipment.

Two thousand Union troops detrained in Grafton on July 1. Arriving to assume overall command of the Union forces in Grafton was Brig. Gen. Thomas Morris of the West Point Class of 1834. In a council of war the following day, Morris outlined a two-pronged assault on Philippi. Morris’s plan was for two columns of equal size to converge on the Confederates in Philippi and fall on them from several directions. The columns were to march east as if they were headed for Harpers Ferry and then turn south. Kelley had 1,500 men from his 1st Virginia, 9th Indiana, and 16th Ohio Regiments. They would entrain in Grafton on the morning of June 2 heading east but then detrain for a 22-mile march south to Philippi. Kelley would enter the town from the northeast with the 1st Virginia and 16th Ohio, and Colonel Robert Milroy would lead his 9th Indiana into position to enter the town from the southeast in to cut off the Rebel retreat.

The other Union force was entrusted to Colonel Ebenezer Dumont, commander of the 7th Indiana. His regiment would entrain after nightfall and travel four miles west where it would rendezvous at Webster with the 14th Ohio, 6th Indiana, and 1st Ohio Light Artillery. The 1,500-man column would then march 12 miles along the Beverly-Fairmont Road. He was to wait for the first light of day and enter the town from the northwest.

“The Philippi Races”

Two young ladies from Fairmont who were sympathetic to the South rode to Philippi to warn Porterfield that a large body of Union troops was on the move. They told the Confederate colonel that they believed there were upward of 5,000 Yankees in the Grafton area based on the troop trains they had seen. Porterfield convened a council of war. Altogether the Mexican War veteran had approximately 600 infantry and 175 cavalry. A few of his officers argued for an immediate evacuation, but Porterfield knew that the green troops could not conduct an orderly withdrawal so he overruled the idea.

A hard rain fell on the night of the Union advance, slowing the march of the columns. At the Rebel camp on the Tygart River in Philippi, discipline was lax among the untested Rebels. The pickets grew tired of standing guard in the rain, and they abandoned their posts to seek a dry place to wait out the storm. The captain of the guard was a drunkard, and he failed to monitor the pickets to ensure they carried out their duties as instructed. Porterfield had sent a cavalry patrol west on the Clarksburg Road to look for the Federals, but they were not using that avenue of approach.

When a decidedly overcast dawn arrived, Dumont’s men were on the outskirts of town. McClellan’s aide-de-camp, Frederick Lander, had guided the column on the main road. Lander was an inveterate explorer who had helped survey possible routes for the transcontinental railroad in the western mountains. In the opaque fog of the summer morning, Lander rode forward on his horse to help the Ohio artillerymen find a good place to unlimber. They unhitched the horses and manhandled a pair of bronze 6-pounders into place atop Talbott’s Hill, a commanding knoll opposite the river from the town.

Kelley’s troops had a hard time keeping to the established schedule for attack on the slippery back roads in the deluge. As Dumont prepared to attack, Kelley’s soaked bluecoats had not yet arrived at their designated position on the southern edge of Philippi. Meanwhile, an altercation occurred on the main road at dawn near Talbott’s Hill. Mrs. Thomas Humphrey, a Confederate sympathizer, ordered her 12-year-old son Oliver to ride into town to warn the Rebels bivouacked in a meadow adjacent to the river. Federal troops grabbed him before he could depart. In a fit of rage, his mother swore at the Yankees and pelted them with rocks. She then pulled a pistol from her bosom and fired at them. The Union soldiers pointed their guns at her, and she retreated into her house.

The Union gunners thought Mrs. Humphrey’s shot was a signal to open fire. They immediately began banging away with their 6-pounders. In the meadow below it was total mayhem. The Rebels rushed out of their tents and ran for their lives. The vanguard of Dumont’s column swept over the covered bridge without encountering any resistance. Kelley’s force streamed into the town from the northeast. When Kelley confronted a retreating Confederate, the man fired his weapon at Kelley striking him in the chest. Although his men thought he would surely die, the former railroad freight agent defied death and made a rapid recovery to the astonishment of his troops.

A few Confederates fired at the Yankees, but Porterfield soon ordered a retreat. This gave the Rebel troops permission to get out town as fast as they could to escape capture. The Rebels conducted “a genuine shirt-tail retreat,” said one Yankee, referring to the fact that many of the Confederates fled half dressed and without their weapons. Newspapers dubbed the Rebels’ hasty retreat “The Philippi Races.” Unfortunately for the Federals, Milroy did not arrive at the south end of the town until the majority of the Confederates had already passed that point.

The losses reflected the almost total lack of combat at Philippi. Five Yankees, all of whom were with Kelley’s 1st Virginia Volunteers, were wounded and two Confederate cavalrymen were severely injured. McClellan, who was soon to join his troops in northwestern Virginia, embellished the victory, calling it “a decisive engagement.” Unfortunately for the Northerners, Porterfield’s men had escaped and would live to fight another day. Kelley, who had almost paid for the victory with his life, was promoted to brigadier two months afterward.

Word spread quickly through Confederate channels of the ignominious retreat. “From all the information that I have received I am pained to have to express my conviction that Colonel Porterfield is entirely unequal to the position which he occupies,” Major M.G. Harmon, commander of Confederate forces in Staunton, wrote to Lee after hearing reports on the precipitous retreat. “The affair at Philippi was a disgraceful surprise, occurring about daylight, there being no picket guard or guard of any kind on duty. The only wonder is that our men were not cut to pieces.”

Lee sacked Porterfield five days later. Porterfield requested a court of inquiry in an effort to clear his name. The court convened in Beverly on June 20 to decide the degree to which Porterfield was negligent in his defense of Philippi. “It does not appear from the record of the court that any plan of defense was formed, but it does appear that the troops retired without his orders, and that the instructions to his advance guard were either misconceived or not executed,” stated the court. Calling the action a disaster, the court conveyed “heavy censure upon all concerned.”

“They Have Sent Me to My Death”

Governor Letcher turned control of all Virginia forces over to the Confederate States of America on June 8. At that point, Lee was without a specific command. Confederate President Jefferson Davis retained him as a personal adviser until an appropriate command could be found for the general.

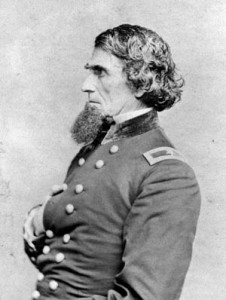

Concerned over the state of affairs in the narrow Tygart Valley, Lee appointed his 41-year-old adjutant general Robert S. Garnett, a member of the West Point Class of 1841, to command the Confederate forces in northwestern Virginia. Garnett had a superb resume. He had been brevetted for bravery twice in the Mexican War, done a stint in the Pacific Northwest, and served both as instructor of tactics and commandant of cadets at West Point.

Garnett was a natural leader of men. He had raven black hair and sported a moustache and beard with whisps of gray. Like all great generals, he never flinched under fire. He knew all too well the sorrow of life, for his wife and infant son had died of Bilious fever while he was on duty in the Washington Territory. The experience had aged him considerably. He immersed himself in his soldierly duties as a way to cope with the tragedy. Garnett was melancholy about his appointment to command the downtrodden Confederate Army of the Northwest. “They have not given me an adequate force,” Garnett said before he left Richmond. “I can do nothing. They have sent me to my death.”

Lee instructed Garnett to prevent the Federals from penetrating the Alleghany Mountains. When Garnett reached Huttonsville, he reorganized the forces under him. From the regiments on hand, Garnett created the 25th Virginia Infantry, 31st Virginia, and 9th Virginia Battalion.

Garnett believed that his forces might best be used to occupy strategic and defensible points on the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. This highway, which connected Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley with Parkersburg on the Ohio River, was of immense strategic importance. This was because nearly all of the roads across the Alleghenies were of the poorest quality, and control of the turnpike was essential for the advance of an army through the high mountains.

Garnett established one fortified camp at Rich Mountain west of Beverly and another at Laurel Hill north of Leadsville. Laurel Hill and Rich Mountain essentially were part of the same long ridge, although the Tygart River flowed through a gap between them. These two positions would block the Federal advance into the Tygart Valley and keep the Federals west of the Alleghany Mountains.

Garnett arrived at Laurel Hill, where he expected the main Union attack, on June 16 to personally supervise its defense. He ordered the troops to fell trees to block all of the roads in the vicinity. They also built breastworks to repulse an anticipated Federal attack. Garnett became deeply frustrated by the lack of reliable intelligence he received from the local population. “The enemy was kept fully advised of our movements … by the country people, while we are compelled to grope in the dark as much as if we were invading a foreign country,” he said.

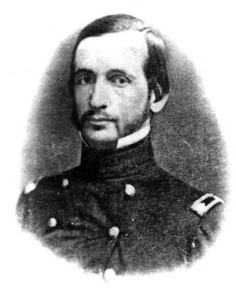

Garnett entrusted the defense of Rich Mountain to Lt. Col. Jonathan Heck, the commander of the 25th Infantry Regiment, who established his main position on the west face of the ridge overlooking Roaring Creek. The 25th Infantry comprised 11 companies drawn from Alleghany and Shenandoah Valley counties. In honor of their commander, the men at Rich Mountain named their bivouac Camp Garnett. Heck would later turn over command of Camp Garnett to Lt. Col. Pegram when the 29-year-old member of the West Point Class of 1854 arrived on July 7.

Confederate Rout at the Battle of Rich Mountain

McClellan arrived in Grafton on June 23 to oversee Federal operations against Garnett’s small force. Although McClellan had upward of 20,000 men, nearly half were involved in guarding key points on the B&O Railroad. McClellan’s plan to crack Garnett’s line was to send Brig. Gen. Morris with 4,000 men to Belington against Laurel Hill. He was to pin Garnett in place while McClellan marched with the main army of approximately 6,000 men to Rich Mountain by way of Buckhannon. While he attended to logistics in Grafton, McClellan entrusted Brig. Gen. Rosecrans to lead three brigades to Buckhannon where they arrived on July 2.

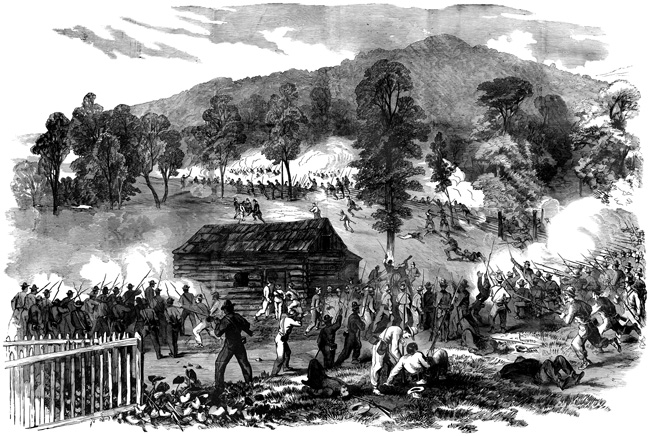

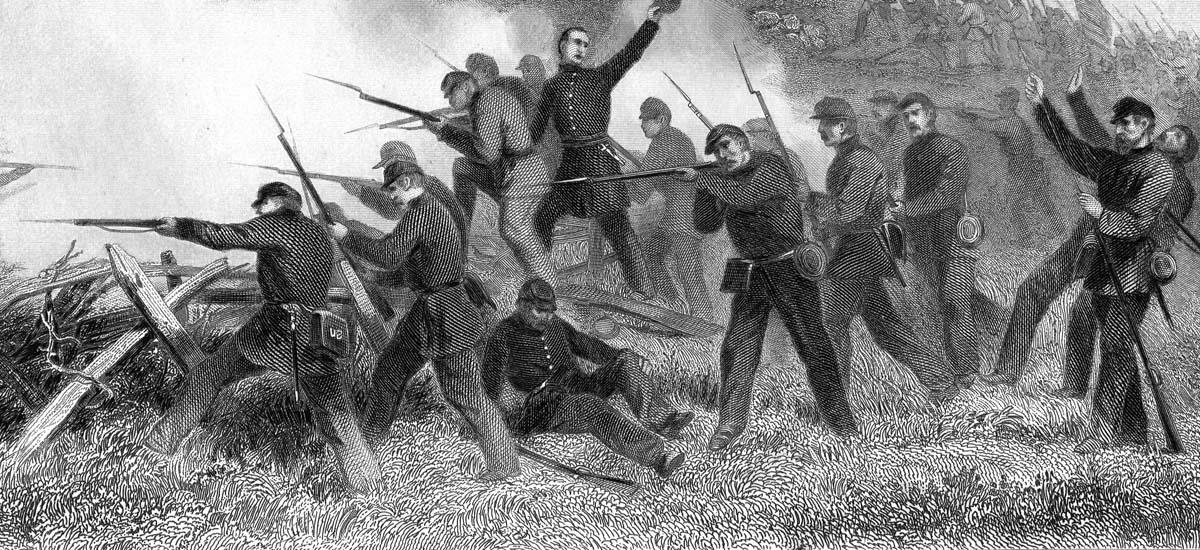

As Rosecrans’s men emerged from the woods onto the summit of Rich Mountain at 2:30 pm after 10 hours in the woods, rebel sharpshooters quickly felled three of the Yankees. The commander of Confederate forces on Rich Mountain had been informed that McClellan’s army might try to flank him, but he considered such an attempt unlikely in the rugged terrain, which had its share of steep ravines and jagged bluffs. Nevertheless, Pegram dispatched 310 men drawn from his 20th Virginia Regiment, Heck’s 25th Virginia, and the 14th Virginia Cavalry to the summit with one 6-pounder gun. Artillery Captain Julius DeLagnel commanded the scratch force. They set up their position on the opposite side of the Parkersburg-Staunton Turnpike from the Hart house. During their short time at the summit, DeLagnel put his men to work constructing a breastwork to strengthen their position.

When Yankee rifle fire began to crackle at the tree line, the Rebel gunners turned their gun south to face the attackers. The rainstorm, which had abated for a time, resumed with a vengeance just as the battle began. The rebel gun banged away at the 10th Indiana Regiment as it deployed in the open. The Rebel gunners were able to get off about four rounds a minute, and their case shot caused considerable havoc among the Yankees, who lacked artillery to oppose it. Rosecrans proceeded cautiously with his deployment, which meant that his vanguard was under fire for 40 minutes before he ordered a general advance.

Colonel Samuel Beatty sent his 19th Ohio Infantry forward to expand the Union battle line in the open field. The Yankees advanced steadily, closing the distance between them and the enemy to 100 yards. Stinging volleys from the blue ranks struck the artillery horses, forcing Lieutenant Charles Statham to redeploy his gun next to a log stable. He ordered his men to take the horses behind the stable. Yankee sharpshooters took up strong positions from which they targeted the Rebel artillerists. Bullets whistled through the air striking trees, snapping twigs from bushes. Statham lost most of his crew in a short time. When a Union soldier panicked and ran past his officers toward the woods, Rosecrans intercepted him and smacked him with the flat of his sword to get him back to the battle line.

Rosecrans eventually tired of the casualties his troops were suffering from the well-served Rebel gun, and he ordered his men to charge. “Huzzah,” the bluecoats screamed as they rushed across the open ground toward the Rebel line. Statham switched to canister to inflict as many casualties as possible on the detested Yankees. Just as the Yankees were sweeping the field, Pegram arrived with 50 men and another gun. The Union soldiers changed face and fired a thunderous volley at the Southern reinforcements.

Rosecrans had every reason to be proud of his troops. They had seized the summit after a grueling flank march and, although weary from the march, whipped the “Secesh” in a two-hour fight during which the lone Rebel gun had fired an estimated 165 rounds.

Pegram tried to lead his 600 troops out of the predicament in which they found themselves with Union troops surrounding them. The day following the battle, Pegram mistook Confederate troops in Beverly for Union soldiers and therefore headed north toward Laurel Hill. Next, he learned that Garnett already had departed the Tygart Valley. He called a meeting with subordinate officers. One of those at the meeting was Captain J.B. Moomau, the commander of Company F (Franklin Guards), 25th Virginia. He told Pegram that he could lead his men to safety by way of a mountain road leading east through the Alleghenies. Pegram declined the offer. Moomau had no intention of surrendering and led the 40 members of the Franklin Guards to safety. On the morning of July 13, Pegram sent word to the Union army that he wished to surrender. “[Due to] the reduced and almost famished conditions” he had no choice but to give up, Pegram told McClellan, who accepted his surrender.

Other Confederates who had fought on Rich Mountain also escaped. Jed Hotchkiss, a topographer, led the 70 men of the 25th Virginia to safety. His understanding of the terrain was the key to their escape. In addition, Colonel William Scott’s 44th Virginia, which Pegram had instructed to deploy on the east face of Rich Mountain to support him, was able to escape the trap that was closing on the Confederates.

Garnett Killed in the Federal Pursuit

Garnett was eating supper outside his tent on the evening of July 11 unaware of the disaster that had taken place at Rich Mountain. Federal guns to his front were shelling him as part of the feint against his position while the main attack occurred to the south. One of the shells slammed into the ground near Garnett, spraying dirt into his coffee. He nonchalantly dumped out the coffee and continued to eat his meal.

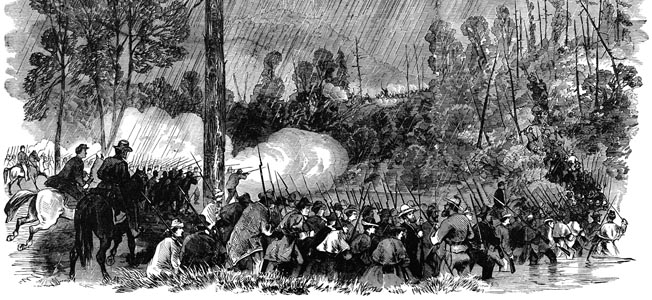

Later that evening a messenger arrived with news of the tragedy that had befallen Pegram’s force. At Laurel Hill, Garnett ordered his men to break camp immediately on the night of July 11. Despite a driving rain, his force was able to get their wagons on the road south to Beverly. When Garnett’s column reached the outskirts of Beverly on the morning of July 12, however, their scouts mistook Confederate soldiers retreating from Rich Mountain for Federal troops. Garnett had to think quickly. He countermarched toward Laurel Hill and then turned northeast on a back road along Leading Creek.

Garnett’s retreating column not only would have to contend with poor roads, but have to cross several rivers that might be flooded because of the continuing rain. Moreover, Garnett would have to contend with the Federals who were sure to pursue his column. Garnett did his best to lead his army to safety, but Federal troops attacked the rear of his column repeatedly on July 13. Morris assigned Captain Henry Benham of the U.S. Army to lead a brigade-sized force to overtake the fleeing Confederates. A running battle occurred along Shaver’s Fork of the Cheat River during which Garnett was slain by Federal troops.

Lee’s Promotion to Full General

Following the Battle of Rich Mountain, President Abraham Lincoln summoned McClellan to Washington. On July 26 Lincoln offered McClellan command of the Army of the Potomac, which the general accepted. In the wake of McClellan’s departure, Rosecrans assumed overall control of Union forces in northwestern Virginia. He divided his troops between Elkwater at the southern end of the Tygart Valley and Cheat Mountain on the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. Command of the Union forces at Cheat Mountain fell to Colonel Joseph J. Reynolds. He was instructed to seize Cheat Mountain Pass on the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis dispatched Lee to personally direct operations in northwestern Virginia. Lee was not traveling west to take control of an army but rather to direct and coordinate the armies of the mountain region in both the northwestern and southwestern theaters of Virginia. The Confederate government in Richmond appointed curmudgeonly Brig. Gen. William W. Loring to succeed Garnett as the commander of the Army of Northwestern Virginia. Loring arrived in Monterey on July 24 to assume command of the forces that had been led in the interim by Brig. Gen. Henry R. Jackson. Lee arrived four days later to coordinate command of all Confederate forces in western Virginia. This included not only Loring’s force, but also forces under Brigadiers John Floyd and Henry Wise in southwestern Virginia.

Lee soon would see some of the most dismal conditions he would experience during the war. It rained for weeks in the Alleghenies, making the roads barely passable and supplying the troops extremely difficult. Many of the troops succumbed to measles and a malignant fever that rendered half of the army ineffective.

The Confederates that Garnett was leading out of Tygart Valley when he was slain eventually made it to Monterey. Loring spent the next six weeks whipping the Confederate forces in Monterey into shape. He ordered Brig. Gen. Jackson to take 5,000 men and advance to the Greenbrier River. Loring marched the rest of the troops southwest to Huntersville to oppose the Union forces at Elkwater.

Loring, who had outranked Lee in the old army, was rankled that Lee would be monitoring and even directing his actions. This did not bode well for the Confederate cause. The Confederate government promoted Lee to full general on August 31, though, making it abundantly clear to everyone that he was Loring’s superior. From that point forward, Lee took control of the campaign issuing orders through Loring. When Lee received his promotion, Loring became more compliant.

Special Order No. 28

In the meantime, Reynolds’ Federals had occupied and begun entrenching on Cheat Mountain. They also held the adjacent mountain pass on the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike, which was situated west of the summit. Reynolds assigned Colonel Nathan Kimball to take 300 men from the 14th Indiana and occupy the fortified camp on Cheat Mountain called Fort Milroy. Reynolds was deployed to the southwest with 1,500 Federals at Elkwater.

Lee devised a complex plan embodied in Special Order No. 28 that called for five separate Confederate columns to strike the Federals on Cheat Mountain and at Elkwater. Three columns would converge on the Federals at Cheat Mountain, and the other two would advance on the Federals at Elkwater.

Colonel Albert Rust would lead the first column from the Greenbrier River up a narrow path that would enable it to turn the flank of the Union forces atop Cheat Mountain. Jackson would lead the second column from the Greenbrier River to a point on the eastern face of Cheat Mountain where it would divert attention from Rust. Brig. Gen. Samuel Read Anderson would lead the third column from Valley Mountain to the west face of Cheat Mountain to block the Federals’ retreat once they were dislodged from the mountain.

Brigadier General Daniel Smith Donelson would lead the fourth column from Valley Mountain along the east side of the Tygart River to get behind the Union forces at Elkwater, while Colonel Jesse Burks would lead the fifth column from Valley Mountain up the west side of the river to Elkwater. Loring, who was given Colonel William Gilham’s brigade as a reserve force, would oversee Burks’ advance.

Rust’s soldiers set out on a grueling march on September 11. They had to ford the freezing waters of the Cheat River and then march single-file up a steep path toward their objective. Rust reached a point squarely behind Reynolds’ force without being discovered. The Confederates camped for the night and reconnoitered the fort’s defenses the following day. But Rust decided not to launch an attack. Because the sound of Rust’s guns was supposed to be the signal for the other four columns to attack, the other columns never received the signal to advance.

In the Tygart Valley, Donelson’s troops, who feared that their powder was wet from recent rains, fired the charges in their rifles in order to reload. This alerted the Federals that an attack was imminent, but it never came. Lee had devised an overly complex plan that depended on too many variables and failed to take into account that the officers leading the columns were not capable of pressing their attack using their own initiative. Lee called off the failed offensive on September 17.

Confederates Hold at Camp Alleghany

On October 3 a small engagement took place at the Confederate’s Camp Bartow on the Greenbrier River. This time it was the Federals who took the offensive. Reynolds led 5,000 men east along the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike in a reconnaissance in force against Confederate positions west of Monterey. Confederate pickets alerted the main force at Camp Bartow. Reynolds ordered his guns to unlimber 700 yards from the Confederate bivouac. Although the Federal gunners knocked out three Rebel guns, they were not able to dislodge the Confederates despite several assaults and sustained bombardment. When Reynolds learned that the Confederates were reinforcing Camp Bartow with troops from Camp Allegheny farther east, he broke off his attack. An outbreak of disease in November ultimately forced the Confederates to abandon Camp Bartow.

Union Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy advanced against Colonel Edward Johnson’s Confederates on December 13. Anticipating a Federal attack, Johnson sent his vanguard to hold the Confederates’ old position at Camp Bartow until the main body of his army arrived. The Confederates sprang an ambush on Milroy’s troops near Camp Bartow. Afterward, the Confederates fell back in good order to Camp Allegheny.

The Federals then switched to the defensive and inflicted substantial casualties on the Confederates before withdrawing to their main camp at Green Spring Run near Cheat Mountain. Johnson held his position at Camp Alleghany until the following spring when Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson attacked Milroy in the Battle of McDowell fought May 8, 1862.

West Virginia Joins the Union

Over the course of the four-year war, the western counties of Virginia sent approximately 25,000 men to fight for the Union and approximately 15,000 to the Confederacy. West Virginia officially became a state on June 20, 1863, during a ceremony at Wheeling. In addition to loyal recruits, the Federal government reaped various other key benefits from control of western Virginia. One benefit was that they controlled the headwaters of the Ohio where valuable coal and salt mines were located. Another benefit was that they had staging areas from which to threaten the Shenandoah Valley and the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad that connected Richmond with Memphis.

As for McClellan and Lee, they soon resumed their contest of arms on a far grander scale west of Richmond in June 1862 when Lee defeated McClellan in the Seven Days Battle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments