By Joshua Shepherd

Across a broad valley near the Greek village of Leuctra, the summer sun beat down on 16,000 anxious Greek warriors. While cavalry horses pranced nervously in front of the lines, officers made final adjustments and offered brief words of encouragement. The city states of Sparta and Thebes, at odds for decades, would finally decide their struggle for power by force of arms.

In the tight ranks of the Spartan phalanx, veteran warriors steeled their nerves for the inevitable terror that awaited. Inexperienced conscripts trembled. The stillness was broken as orders were barked on the Spartan side of the field, setting the army in motion. In unison, the Spartan battle line surged forward, in complete silence according to their training. In the rear of the Spartan phalanx, flute players kept cadence for the men trudging toward the enemy.

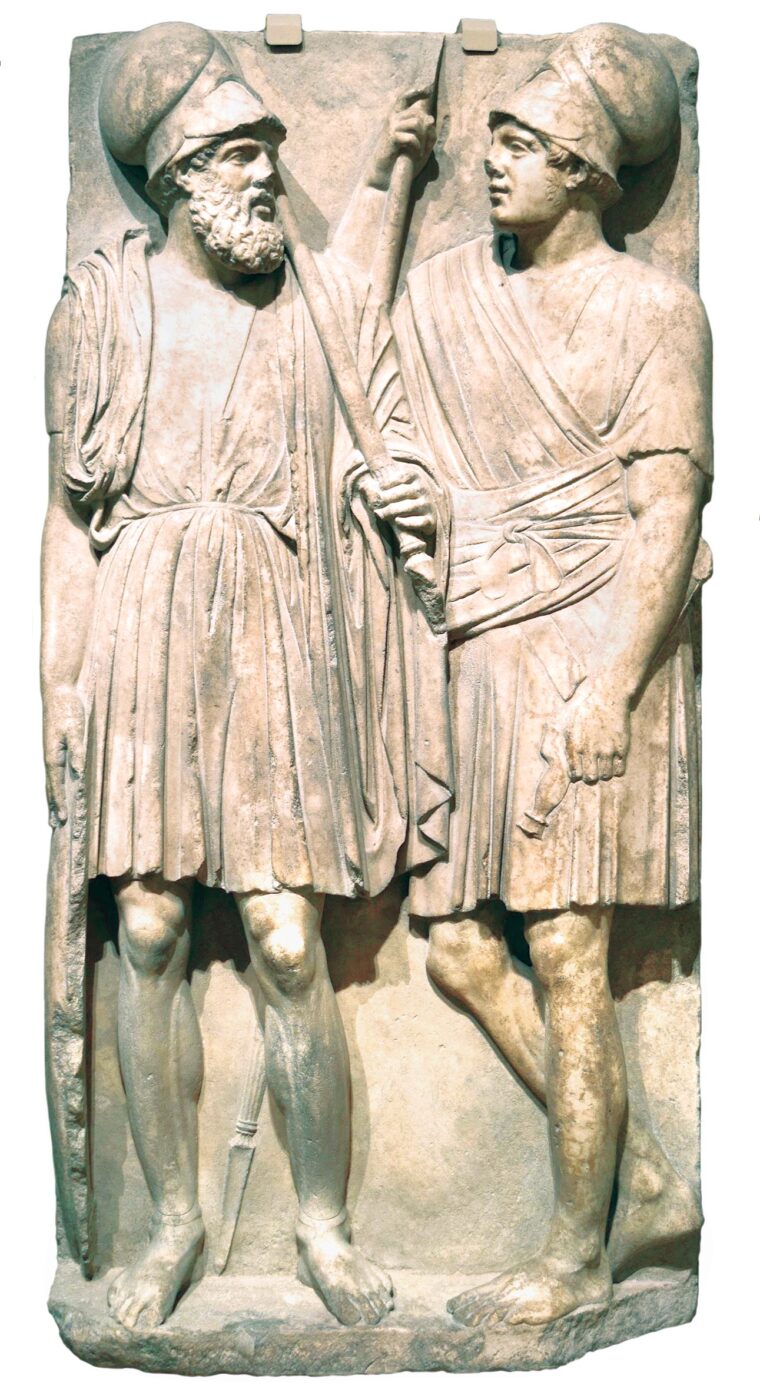

As they neared the Theban phalanx, the Spartans witnessed an enemy line bristling with spears and protected by a solid wall of large, round aspis shields emblazoned with the club of Heracles. The symbol of the great Greek demi-god was used as the insignia of the Sacred Band, an elite group of Theban warriors who had trained most of their adult lives to fight, and crush, the might of Sparta. Within moments, the fate of the Hellenistic world would be decided by the finest warriors of ancient Greece.

For over three centuries, Sparta had been a dominant force among the restless and antagonistic city states of ancient Greece. In early antiquity the city had been little more than a landlocked backwater situated in the narrow valley of the Eurotas River. But the Spartans, hemmed in by mountains and eager for expansion, aggressively sought elbow room at the expense of weaker neighbors.

Sparta sought influence and resources not by diplomacy, but through brute force. After seizing control of surrounding settlements in their home region of Laconia, the Spartans waged a war of outright conquest about 700 BCE. Pushing west across formidable mountains, the Spartans invaded the fertile homelands of Messene. Following a lengthy and bloody war of attrition, the Spartans succeeded in subjugating the whole of Messenia.

Rather than place their new conquest under tribute, the Spartans made an unthinkable decision. The entire Messenian population was enslaved, declared the hereditary property of the Spartan state. The unprovoked enslavement of fellow Greeks shocked the Hellenistic world but facilitated the radical transformation of Sparta.

By forcing the Messenian slaves, or helots, to work the land, Spartan citizens were freed from the constraints of pursuing a livelihood. To maintain the system and expand Sparta’s power, virtually the entire male population was required to enter full-time military service, manning garrisons at home and abroad in a stark exhibition of brute force.

Subjected to a ruthless training regime, brutal discipline, and sparse rations, Spartan hoplites—heavily armed footsoldiers—were the most feared warriors of ancient Greece. While the armies of most Greek city-states comprised short-term volunteers, Sparta fielded veteran troops who were experts at the craft of war.

The comprehensive militarization of Spartan society unsurprisingly led to centuries of dominance across the Greek world. Spartan armies fanned out across the Peloponnesus, subduing the bulk of the peninsula. As a check on unrestrained power, the Spartans developed a novel dual monarchy of not one, but two hereditary kings from separate families, the Agiads and Eurypontids, who were regarded as descendants of the god Zeus. The dual kingship ensured a stable monarchy: only one king at a time could go to war, while his counterpart remained safely in Sparta.

Farther north, the cities of Attica and Boeotia, foremost among them the grand metropolis of Athens, scrambled to maintain their independence against the specter of an ascendant Sparta. Although the Greek states occasionally united to confront the repeated threat of Persian invasion, old rivalries died hard. And as Sparta increasingly flexed its muscles, full-scale conflict became all but inevitable.

Beginning in 431 BCE, an apocalyptic conflict rent the Greek world. In a wide arc from Sicily to Asia Minor, Athens and Sparta, along with their allies, unleashed a horrific total war that witnessed loss of life, famine, and destruction on an unprecedented scale. In 404, Sparta finally succeeded in forcing the surrender of Athens.

In the wake of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta became the dominant power of the Hellenistic world, wielding influence across a wide swath of the Mediterranean. Puppet governments friendly to Sparta were installed in a number of minor states.

Not surprisingly, however, the fiercely democratic city states of ancient Greece grew increasingly restless in the face of Spartan hegemony. Despite long-standing Spartan dominance in the Greek world, a new power was on the rise by the fourth century BCE. Thebes, situated northwest of Athens, was a restless city state intent on flexing its muscles and freeing itself from outside domination.

Thebes occupied a dichotomous role for much of its history. Situated in the center of Boeotia, the town sat at the very crossroads of empire. Boeotia was a comfortable region characterized by flat terrain and fertile farmland. The Boeotians consequently prospered, but were slow to develop militarized states compared with the superpowers of Athens and Sparta.

The city of Thebes, the largest and most powerful city of Boeotia, wielded great influence over her neighbors but was, in turn, repeatedly subjected to the control of both Sparta and Athens. In the perilous game of Greek diplomacy, Thebes’ allegiance was constantly in a state of flux between the two larger warring cities.

Boeotia was also situated in ancient Greece’s prime avenue of war. Armies headed toward the regions of Attica or the Peloponnesus necessarily marched directly through the flat terrain of the Theban homeland. So many armies traversed Boeotia that the Roman historian Plutarch aptly referred to the region as “the dancing floor of war.”

Thebe’s increasing diplomatic weight was a natural outgrowth of a strengthening military. Like most rising powers, Thebes possessed a robust citizenry proud of their city’s mounting strength and prosperity. This patriotism manifested itself in greater enthusiasm for military service and a serious approach to training and discipline.

But Thebes could field more than the traditional part-time citizen soldier. Throughout its history, the city had occasionally employed a force of 300 elite troops to bolster the hoplites. But in 378 BCE, Thebes constituted a brand-new crack unit, known as the Sacred Band, which could rival the vaunted Spartans man-for-man.

The Sacred Band was composed of 300 men who were devoted to full time soldiering. The men were unmarried and, freed from the responsibility of raising families, spent the bulk of their time training. In addition to constant drills that stressed the use of weapons and the deployment of the phalanx, the members of the Sacred Band were devotees of traditional Greek sports including running and wrestling. When not on campaign, the troops were housed in the Theban fortress of the Cadmea, and were maintained and supplied by the state so that their full energies could be devoted to the art of war.

Thebes, however, was a hotbed of rival political factions vying for power. Although the city possessed a minority of citizens with pro-Spartan sentiments, Theban patriots, nominally allied to Athens, were predominant. Among the latter were two of the city’s most influential men: Pelopidas and Epaminondas. Pelopidas was the scion of an aristocratic family, immensely wealthy, and by nature and inclination a warrior.

Epaminondas, however, was the quintessential citizen of ancient Greece. Descended from an impoverished family, Epaminondas lived an ascetic lifestyle but was a thoroughgoing Theban nationalist. A skilled orator, he quickly established a name for himself in the Theban political scene and was eventually installed as a Boeotarch, one of seven chief officers who administered the Boeotian Confederacy.

During his lifetime Epaminondas was a dominant force in Thebes, but when duty called he served on the front lines with his fellow citizens. At the Battle of Mantinea, he is credited with having saved the life of Pelopidas. The two would forge a professional friendship that would prove crucial to the Theban city state.

Despite her own internal disorders, Thebes hoped to exploit an inherent weakness in the Spartan state and maintain constant military pressure on her rival. Although Sparta’s militarized society had succeeded in dominating Greece for much of its history, it did so at the expense of its own population. Spartan men, who focused their energies on warfare, spent little time at home, and the family unit suffered accordingly. Over the decades, the population of Spartans citizens dwindled. In the earliest years of Sparta’s history, the city boasted perhaps 9,000 male citizens. By the 4th century BCE, there were fewer than 700.

The ceaseless bloodletting that ravaged Greece was temporarily halted in 387 BCE. Peace talks, ironically called by the Persian King Artaxerxes II, saw envoys from across Greece agree to an armistice. The treaty, known as the King’s Peace, stipulated that Asia Minor be left in Persian control and that all Greek cities “big and small, should be left to govern themselves.” The treaty provision guaranteeing complete autonomy for Greek city states unintentionally laid the foundation for continued war.

When the treaty was officially ratified, Epaminondas suggested affirming the treaty not on behalf of Thebes, but all Boeotia. Seeing the move as a provocative insult from a Theban-dominated Boeotian League, the Spartan King Agesilaus II sternly refused. Hoping to weaken Theban influence in Boeotia, the Spartans refused to officially recognize the League, and maintained troops in the region of Phocis to the west of Boeotia. Unwilling to risk another all-out war, the Thebans backed down. It was a humiliating insult that Epaminondas would not soon forget.

The ugly game of internal Theban politics would ultimately end the brief respite from war. In 382 BCE, the pro-Spartan Theban agitator Leontiades plotted a coup with a local Spartan commander, Phoebidas. On his own initiative and in blatant violation of the King’s Peace, Phoebidas unexpectedly led a Spartan force into Thebes and, with the help of Theban collaborators, seized control of the city. Ismenius, leader of the pro-Athenian faction, fled the city, along with Epaminondas and Pelopidas.

Apprehensive that the incident could reignite the war, the Spartans recalled Phoebidas, but Spartan troops continued to occupy Thebes. King Agesilaus defended his rogue general, and Phoebidas received little more than a reprimand and a fine. Despite having ratified the King’s Peace in 387, the Spartans clearly hoped that they could once again bully their way into dominating the Greek world.

The Thebans were quick to carry out revenge. After three years of galling Spartan occupation, Ismenius’ partisans slipped into Thebes. Among them was Pelopidas, who, true to his reputation as a man of action, was eager to strike a blow. For his part, Epaminondas remained aloof from the plot, and preferred to steer clear of shedding Theban blood. Pelopidas and the nationalists entertained no such scruples; with the help of locals who had grown outraged by the occupation, the Thebans assassinated the pro-Spartan collaborators who had been ruling the city. With the help of Athenian troops, the Thebans then succeeded in expelling the Spartan garrison from the city.

Not surprisingly, the King’s Peace began to unravel across Greece. Hoping to forestall a resurgence of Spartan dominance, Athens and Thebes formed a confederacy of Greek states to present a united front to Spartan encroachment. The new league announced that it had been formed “so that the Spartans may allow the Greeks to live in peace, free and autonomous, with all their territory secure.”

Eventually over 60 cities joined the confederacy in the hope of avoiding the shameful Spartan occupation that Thebes had endured. The new league, it was proclaimed, would admit no foreign “garrisons or magistrates.”

The league was an unacceptable threat to the Spartans, who could see their influence in Greece on the wane. War ensued. Under Athenian leadership, the league poured its resources into an impressive fleet. Their investment paid off in 376 BCE, when the allies badly mauled a Spartan fleet at the Battle of Naxos.

The following year, the Spartans suffered a rare defeat in a pitched land battle. Hoping to drive a garrison of Spartan troops out of northwestern Boeotia, the Thebans dispatched a flying column under the command of Pelopidas, which consisted of 200 cavalry and the 300 crack hoplites of the Sacred Band. The Thebans unexpectedly encountered a superior Spartan force in a narrow mountain pass near Tegyra and had little choice but to stand and fight.

The Spartans, with about 1,200 men, were confident that they would handily brush aside the small Theban force. But Pelopidas drew up his entire force in a dense column that launched a fierce attack against the enemy right, the traditional place of honor where the Spartan commanders were sure to be located. The Sacred Band proved its worth, smashing through the enemy right, where the two Spartan commanders were killed. Although the Battle of Tegyra was considered a minor affair, the invincibility of the Spartan hoplite was demonstrated to be an antiquated legend. Pelopidas, as well as the members of the Sacred Band, enjoyed greater confidence in facing the Spartans again.

The Thebans, confident that their city was on the rise and capable of humbling Sparta, rejected overtures for a new treaty. Thebe’s attempt to become a rival power was clearly a threat that Sparta felt obliged to confront once and for all. An invasion of Boeotia was planned for the campaign season of 371 BCE. While the elder King Agesilaus remained in Sparta, his younger counterpart, King Cleombrotus, would lead the assault against Thebes.

Cleombrotus, already occupying the city of Coronea to the west of Boeotia, commanded a sizable force more than capable of launching an invasion. The king eventually mustered a force that numbered about 10,000 men, which included hoplites, a mix of light troops, and a force of some 1,000 cavalry. The light troops and cavalry were vital for screening and foraging operations, but the real core of the army constituted the heavily armed hoplites. The bulk of the hoplites were conscripted from Sparta’s vassal states and allies in the Peloponnesus. A dedicated core of just 700 Spartan citizens would form the backbone of the army.

Breaking through to Boeotia, however, could prove problematic. The easiest route to the Theban homeland, which passed south of Lake Copais, was nonetheless blocked by Theban forces in mountain passes east of Coronea. Forcing a direct passage could prove an immensely bloody affair. Cleombrotus formulated an intricate plan to steal a march into Boeotia by minor mountain passes which the Thebans would likely neglect to guard.

Rather than move directly east from Coronea, Cleombrotus ordered his army to march by a wide, circuitous route, first to the west, then in a wide arc to the south and east. His army skirted the Corinthian Gulf to the south, and their movement was masked by rugged mountain ranges to the north. The Spartan force slipped through narrow mountain passes west of Creusis completely unnoticed by the Thebans. After emerging onto the rich plains of Boeotia, Cleombrotus was in a position for a drive into the Theban heartland.

For their part, the Boeotians had hastily formed an army of 6,000 men for the defense of their homeland. The army included a solid core of Theban hoplites, bolstered by troops from various Boeotian city states. More importantly, the army also included the elite Sacred Band under the command of Pelopidas.

Curiously, the army was not led by a single commander, but by seven Boeotarchs. Six of the Boeotarchs remained with the army, while a seventh, Brachyllides, commanded a smaller detachment that guarded a vital mountain pass at Mount Cithaeron. Although Epaminondas was a charismatic commander that possessed a forceful personality, his leadership among the Boeotians was by no means without challenge.

If they had any hopes of forestalling an invasion on their homeland, the Boeotians had little choice but to head toward the Spartan army. Theban scouts located the Spartans near the town of Leuctra, camped along a ridgeline overlooking a broad plain. Epaminondas and his fellow Boeotarchs led their army to an opposing ridgeline, where they set up camp on the opposite side of the valley from the Spartans.

Although the Thebans had fielded an impressive army capable of confronting the Spartans, the Boeotian high command was divided over what course to take. With the Spartan army in plain view along the opposing hillsides, several of the Boeotarchs voiced reservations over giving battle.

A trio of the leaders—Damocleidas, Damo-philus, and Simangelus—argued that fighting a pitched battle under the current conditions was too risky. Victory, they argued, was by no means assured, and a Theban defeat would leave all of Boeotia open to the ravages of the Spartan army. The hesitant Boeotarchs advocated for retreating with the army intact, evacuating the civilian population to the safety of Athens, and then seeking battle under more favorable conditions.

Epaminondas, joined by the Boeotarchs Xenocrates and Malgis, would have none of it. Epaminondas argued that all of Boeotia had contributed to assembling a large army, the enemy had been located, and there was no guarantee that a more favorable battlefield would ever present itself in the future. Pelopidas had already proven that the Spartans were no longer invincible, and the Sacred Band was present and itching for a fight. Although victory wasn’t guaranteed, Epaminondas asserted that a fight under the current circumstances was worth the risk.

The six Boeotarchs, evenly divided in sentiment, had reached an impasse. In an army governed by the consensus of multiple commanders, the disagreement proved crippling. In the face of the enemy, the Thebans were unable to make a binding decision one way or another.

When all seemed hopeless, Epaminondas experienced a fortuitously timed stroke of luck. Fresh troops arrived in camp. It was the detachment of men who had been guarding the Cithaeron Pass, led by the seventh Boeotarch, Brachyllides. After the discussion was renewed, the newly arrived Boeotarch weighed the options and then cast his vote with Epaminondas. With the deadlock broken, Epaminondas could finally put the entire Boeotian army into motion. The Thebans would give battle.

From the hills surrounding the plain of Leuctra, the finest warriors of Greece broke camp and formed long, sinuous lines as they marched for the valley floor. Although the surrounding hills were dotted with scrub growth, the plain was free of underbrush and an ideal locale for the deployment of the hoplite phalanx. Although relatively flat, the valley possessed a gentle slope that descended toward the Spartan side of the valley.

As he made dispositions for the coming fight, Epaminondas developed an unorthodox plan. Long standing Greek tactical doctrine called for an army’s strongest contingent to occupy the place of honor on the right flank. Epaminondas chose an unexpected opposite course. While placing a thinner line of his Boeotian allies on his right, he placed his strongest contingent, the Theban phalanx, on his left. Foremost among them were the 300 men of the Sacred Band, commanded by Pelopidas and occupying the front ranks.

Epaminondas likewise ordered the troops on his left to form an exceptionally deep phalanx. Ancient sources differ, but the left wing of the Theban army was between twenty-five to fifty ranks deep. It was a massive phalanx never seen before on a Greek battlefield. The unprecedented formation was a powerful hammer with which Epaminondas hoped to smash the power of Sparta.

To ensure the success of the plan, Epaminondas arranged another tactical innovation that used his own weaknesses to his enemy’s disadvantage. Realizing that the Boeotian allied troops would likely not perform very well when battle was joined, the Theban general decided to arrange his entire army in an oblique formation, leading with his powerful left wing.

Allied auxiliaries on his right wing were angled away from the enemy line and given free rein to give ground to the Spartan attack. By doing so, the Spartan left would be inevitably drawn farther from its own lines and away from the epicenter of the battle. When and if the Thebans cracked the Spartan right wing, the Spartan left wing would not be in a position to render aid.

From his vantage point, the Spartan King Cleombrotus formed up his army in a conventional phalanx. Although it was impossible to precisely discern enemy strength, it was obvious that the Thebans had formed an exceptionally dense phalanx. Although Spartan armies traditionally formed eight ranks deep, Cleombrotus responded to the Theban threat by forming his own phalanx twelve ranks deep. His lines presented a formidable sight of glinting steel and crimson cloaks, which were the traditional badge of Spartan citizenship.

The Spartan king personally commanded the right wing of the army, which was made up of some of his best troops, including his personal bodyguard. The 300-man royal guard, known as the hippeis, was considered an elite unit even among the Spartans.

The center of the line was manned by allied hoplites drawn from city states across the Peloponnesus. The allied troops added much needed extra manpower but were generally considered of questionable loyalty in a tough fight. The left wing of the line was occupied by another contingent of crack Spartan troops commanded by prince Archidamus, son of King Agesilaus. Although the allied auxiliaries in the center would likely not fight with great resolution, they could be expected to hold their own while the Spartan contingents smashed both enemy flanks.

Out in front of both armies trotted contingents of cavalry. The horsemen were generally lightly armed and wore little more than cloth tunics. Greek cavalry was used for screening and scouting duties but posed little threat to an enemy phalanx. Infantry dominated the tactical landscape of ancient warfare. As the sun soared over the valley, thousands of Greeks nervously peered at their enemy. For the men who would battle at Leuctra, the coming fight would be a horrifyingly personal affair. Hoplites waged war face to face with their enemy, and killing was a fierce contest of brute strength, iron discipline, and sharp steel.

While both armies made final adjustments to their infantry lines, the opposing cavalry forces began skirmishing in the no-man’s-land between the Spartans and the Thebans. Fighting in irregular order, knots of horsemen dashed toward their counterparts, looking for opportunities to strike. Primarily resorting to their lances, Greek fought Greek in a wild melee of dashing and thrusting.

Although immense dust clouds were stirred up by the horse’s hooves, the cavalry fight seems to have been little more than a minor tussle. With little real fighting to be done by the lightly armed cavalry, the horsemen quickly disengaged and galloped for the rear of their respective armies. They would play little role in the coming battle, but waited patiently for the outcome of the contest in preparation to exploit any victory.

With the battlefield clear of horsemen, both sides set their phalanxes in a slow but steady march toward the enemy. Few commands were needed for the well-disciplined hoplites, and the field was quiet save for the low rumble of thousands of fighting men on the march. On the Spartan side of the field, flute players kept time for the advancing men. Flushed with adrenaline as they closed the distance to the enemy, men broiled under their bronze armor.

For the men in the very first rank, the psychological terror was most intense; with the enemy approaching from the front and their own men pushing from the rear, the front lines of a Greek phalanx could suffer horrific casualties in the brutal meat grinder of ancient warfare. As the two armies closed the distance, the Boeotian line was angled toward the left as planned by Epaminondas. The Spartan line unintentionally developed into a reverse crescent: while the two Spartan wings moved forward as planned, the center, occupied by Peloponnesian allies, lagged behind.

As the two sides collided, a terrifying cacophony of clashing iron and shouting men peeled across the valley floor. The initial fighting was a fierce test of wills as some of the finest warriors of ancient Greece clashed face to face. Combat in the phalanx was a horrific experience; for men in the front ranks, it was often a death sentence. At Leuctra, there was little room for elaborate tactics once the battle was joined. Men fought and died with little glory; the fortunate casualties were killed quickly; others were crushed in the massive press of men.

Initially, the Spartans held their own as both lines grappled for supremacy. The Spartan reputation of discipline, ingrained after centuries of tradition, was by no means a hollow legend. The Spartan right bristled with trained warriors, and men from both sides fell by the score.

But as pressure from the massive Theban phalanx began to tell, the Spartan lines began to crack. According to their training and tradition, Spartan hoplites were loath to break ranks or surrender. But the sheer weight of numbers caused the Spartan front ranks to give way. Spartans fought until overwhelmed or were simply pushed to the rear by the seemingly irresistible Theban steamroller.

The Roman historian Plutarch recorded one notable example of unbending Spartan tenacity. Fighting in the front ranks of the Spartan phalanx, the young nobleman Cleonymus fought with steely resolve, side-to-side with fellow citizens. As the crushing weight of the massive Theban phalanx began to break through, Cleonymus was wounded and knocked down three times, struggling to his feet each time in a desperate attempt to regain his position in a crumbling line. Weakened by successive wounds and exhausted by the sheer strain of battle, the young nobleman was finally overpowered and killed.

Fighting ferociously beside his bodyguard, King Cleombrotus refused to give ground. The hippeis warriors stood firm beside their king, thrusting violently with their spears in a desperate attempt to hold the Thebans at bay. Far from rallying his demoralized troops, Cleombrotus had inadvertently placed himself in a hopeless situation.

Swarms of Thebans continued to pour into the gaps in the Spartan lines and batter the remains of the Spartan phalanx further to the rear. Cleombrotus, trapped with a dwindling knot of his guards, remained true to the Spartan warrior ethos and fought stubbornly as masses of Thebans wrapped around his flanks. The Spartan royal guard was overpowered, and as exultant Thebans rushed in for the kill, Cleombrotus fell dead in the melee. His death constituted a staggering blow for a Spartan royal house whose lineage stretched back for centuries.

With the king dead on the field, Spartan cohesion quickly fell apart. Although disciplined Spartan soldiers were legendary for their stubborn refusal to retreat, the realities of the ancient battlefield belied that reputation. With the phalanx broken down, individual Spartan hoplites were easy prey to the Thebans, who ranged through the battlefield shouting, cursing, and killing with wild abandon.

The crucial Spartan right wing, the key to the entire army, had been effectively crushed. Panicky fugitives streamed for the rear in a desperate attempt to escape the Theban killing machine. But rather than pursue the retreating Spartans, Epaminondas and Pelopidas reined in their troops and wheeled their massive phalanx to the right. Theban training paid off. An organized Theban line began pushing along the length of the enemy army, unexpectedly tearing into the exposed flank of the Spartan allies who occupied the center of the battle line.

For troops who were less than eager to fight, the Theban flank attack was a crushing blow. The Peloponnesian center simply collapsed, with demoralized troops streaming for the rear in utter confusion. Those unfortunates unable to escape the field were simply cut down by the rapidly advancing Thebans.

On the Spartan left, Archidamus quickly appraised the peril of his advanced position. Realizing that the Spartan left was badly exposed and subject to being cut off in flank and rear, the prince immediately gave up pursuit of the enemy to his front and ordered a hasty retrograde. Spartan warriors raced west along the valley floor, skirting along the hillsides in an attempt to escape the rapidly closing Theban trap.

The disorganized remnants of the Spartan army streamed to the west, making way as best they could for the city of Leuctra. Epaminondas eventually opted not to press his advantage too far and decided not to seek further battle. Spartan leaders including the prince Archidamus attempted to bring order to the shaken fugitives, but it was obvious that the crushing defeat at Leuctra had ended Spartan ambitions in central Greece.

In the aftermath of the battle, the broad plain at Leuctra was a scene of horror. The brutal nature of close-quarters ancient warfare left the stricken with ghastly wounds. The field was strewn with the dead and dying; trampled grass was streaked red with the blood of the slain and littered with the scarlet cloaks of the Spartan dead. As the exultant shouts of victorious Theban warriors echoed across the valley, wounded men called out for water and mercy.

The Thebans, sensing that the battle would occasion a tremendous rebalance of power across the Hellenistic world, commemorated the great victory by erecting a grand monument on the center of the battlefield. Epaminondas’ reputation soared in the aftermath of the fight, further cementing his grip on the levers of power in Thebes. The city, which had long been considered a second-rate city state in the shadow of Sparta and Athens, became the dominant force in central Greece.

For Sparta, the pitched battle at Leuctra had been nothing short of calamitous. Of the 700 citizen hoplites present at the battle, it is thought that 400 had been killed on the field. It was a staggering blow to the city’s population from which it would never fully recover. After its last great play for power had ended in disaster, it was clear that the once-great Spartan state, as well as its dreams of empire, had entered an irreversible decline. Henceforth, Sparta was forced to defend its shrinking borders with Peloponnesian subjects and foreign mercenaries. It was a recipe for failure.

The collapse of Sparta had been set in motion by Epaminondas’ innovative tactics on the battlefield of Leuctra, but carried out by the grim dedication of Theban hoplites who were determined to defend their homeland. The Theban citizen-soldiers, quipped the Greek historian Diodorus, had crushed the Spartan elites, once considered the “invincible leaders of Greece.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments