By William E. Welsh

When summer arrived in Bavaria in late June ad 955, thousands of unwelcome barbarians from the Carpathian basin were gathering on its eastern fringe, poised to invade the southern part of the East Frankish kingdom once again. The Magyars had slowly migrated west over nearly a millennium from their homeland beyond the Ural Mountains of Central Asia to resettle in the steppes on the fringe of Western Europe. Now they had assembled in force on the eastern bank of the Enns River, ready to fan out across the rolling hills looking for any opportunity to steal and rob those living in exposed villages and farms.

The farmers and peasants had vivid recollections of Magyar raids punctuated by orgies of death and destruction much like those perpetrated by the Huns and Avars who had preceded them centuries before. In mortal fear of the Magyars, the majority of the Bavarian farmers and villagers packed up their belongings and moved into cramped quarters inside walled cities and strongholds scattered throughout the duchy. They awaited salvation from 43-year-old Saxon King Otto, whose sword had been dipped many times in the blood of Magyars, Slavs, and rebels from within his own realm.

The Magyars’ Way of War

The Magyars would be fighting the weather as much as the enemy. Heavy storms had flooded alpine tributaries to the mighty Danube, lessening the effectiveness of the Magyars’ deadly composite bows and slowing their movement by horseback across the countryside. The year before, thousands of the fierce mounted bowmen had rampaged through the East Frankish kingdom on the first leg of an epic raid that swept through Bavaria, Swabia, and Franconia, on into Lower Lorraine and Burgundy, and back to the Carpathian Basin via Lombardy. Although the raid of 954 was considered remarkable for its scope and duration, it had not gained the Magyars enough booty to support their nomadic lifestyle, nor had it instilled enough fear in those they plundered to generate a willingness to pay them enough tribute to refrain from similar raids.

Otto had emerged the victor after a two-year civil war against rebellious East Frankish nobles and had returned to fighting his old nemesis, the Transelben Slavs, east of Magdeburg. To the south, one of the king’s key allies, Bishop Ulrich of Augsburg, watched as laborers toiled to strengthen the city’s ramparts in anticipation of another Magyar attack. To the northeast, Conrad the Red, Duke of Lorraine, one of the nobles who had plotted with Otto, had returned to the king’s fold and stood ready in Franconia with 1,000 heavy cavalry to block one of the favorite invasion routes of the Magyars. To the east, Duke Boleslav of Bohemia, another of Otto’s allies, had mobilized 2,000 men and stood poised to march to the Germans’ assistance.

Throughout the duchy of Bavaria that summer, local troops steadfastly loyal to Otto manned dozens of forts and strongholds located at key crossing points along right-bank tributaries of the Danube awaiting the onslaught. Although Otto was tied down that summer fighting the Slavs, he had established a defense-in-depth strategy designed to slow the Magyars and bring them to battle, something they steadfastly avoided against the more heavily armed German troops.

As light cavalry, the Magyars were loath to fight at close quarters with the more heavily armored German heavy cavalry. The Magyars’ primary weapon was the composite bow, which was crafted of sinew, wood, and horn. The nimble horsemen typically fired arrows, which were strong enough to penetrate mail armor, from a safe distance at their opponents. They preferred to fight in wide-open spaces, where, if the battle went against them, they could quickly disperse and escape. This style of fighting had two major drawbacks. First, the bows were not effective in wet weather. Second, they could not fight in heavily wooded terrain that blocked the flight of their arrows. Preying largely on unprotected villages and farms, the Magyars almost never brought along the slow-moving infantry and heavy siege weapons that were essential to capturing fortresses and walled cities.

Unlike previous raids, the Magyar chieftains intended to bring along slaves to stand and fight as infantry and haul great siege engines across the Bavarian plain. The strategy carried great risk, as the Magyar infantry would be inferior to their German counterparts, and also because the foot soldiers and siege train would slow their advance and rule out any element of surprise.

The Invasion of Bavaria

Magyar envoys traveled to Magdeburg, ostensibly to show their support for the German king but in reality to take stock of whether Otto had regained military control of his kingdom. They stayed for about a month, during which time they observed lingering uncertainty among the members of the royal court in the aftermath of the civil war that had only ended two months before. Hoping that Otto would be reluctant to lead his elite force of Saxons and Thuringians into Bavaria for fear another rebellion might break out, the envoys reported back to the Magyar chieftains that the time was ripe for a fresh invasion of Bavaria.

Augsburg, which had been founded by the Romans in 15 bc, was located on the west bank of the Lech River just south of the confluence of the Lech and the Wertach River. It had served over the centuries as a major hub of trade between Germany and southern Europe. Augsburg had the unfortunate distinction of being the least fortified of the major Bavarian cities. The city’s walls had been heavily damaged in the recent civil war, it lacked towers to protect its gates, and the gradually sloping ground on which it was located made it accessible by an enemy using heavy siege equipment. Only the city’s east gate, which rested on a steep bluff over the Lech, would prove difficult to attack with siege weapons.

After the Magyar envoys safely returned to the Carpathian basin in late June, the 25,000-strong Magyar army led by the chieftains Lel and Bulcsu lunged across the Enns River on July 1 and separated into columns to carry out various missions. The swiftest columns intended to ride beyond the Lech as far as the Iller River in an effort to fool the Germans into thinking they were heading deep into Swabia and Franconia to pin down German forces, while the slower columns escorting the infantry and siege weapons aimed for Augsburg. From mid- to late July, the outriding Magyar columns systematically stripped all of the forage that could be found between the Lech and Iller to feed their army and deny a German relief army any sustenance. Meanwhile, the infantry and siege train progressed slowly across Bavaria, averaging only 11 miles per day. The Magyars ransacked far and wide, once again spreading terror. Those who could take refuge in fortresses or strongholds did so, but many could not escape the barbarians’ depredations.

Before falling back to the Lech at the close of July, the commander of the vanguard of the Magyar army had arranged for a spy to watch for Otto’s relief army and notify the Magyars of his pending arrival. The traitor, Berthold, established himself at Reisensburg, which was located on the old Roman road between Ulm and Augsburg south of the Danube. If Berthold could provide information as to the direction and timing of Otto’s advance on Augsburg, the Magyars might be able to plan an effective ambush.

Magyars Assemble at Lechfeld

Following the rebels’ defeat, Otto had shifted his base of operations back to Magdeburg to resume his campaign against the Slavs. While conducting operations in that sector in early July, he received an urgent message from his brother, Duke Henry of Bavaria, which read, “Beware, Hungarian war bands, fanning out, have attacked across your frontiers.”

Otto’s first order of business was to draft dispatches requesting military assistance from his nobles and bishops and also from key allies, such as Duke Boleslav of Bohemia, ruler of a principality that lay outside of the East Frankish kingdom. Once this was done, Otto led his personal legion of 1,000 Saxons and Thuringians south to join forces with other troops assembling in Bavaria to contest the Magyar invasion. Otto might have taken a larger force with him, but he left a sizable army behind to watch the Slavs and prevent a power vacuum in Saxony.

Otto arrived in Ulm, about a two-day march from Augsburg, in late July. The city, situated on the north bank of the Danube, had a large palace and fortress that made it a suitable base of operations. The king initially had contemplated establishing his headquarters at Bopfingen, which lay to the northeast of Ulm, but the Magyar advance toward the Iller indicated that the Magyars intended to turn north into Franconia as they had done the year before. The king deployed the arriving Bavarians and Swabians to guard the crossing points of the upper Danube above Ulm. Below the town, the river was too wide for an army to cross without ferry boats.

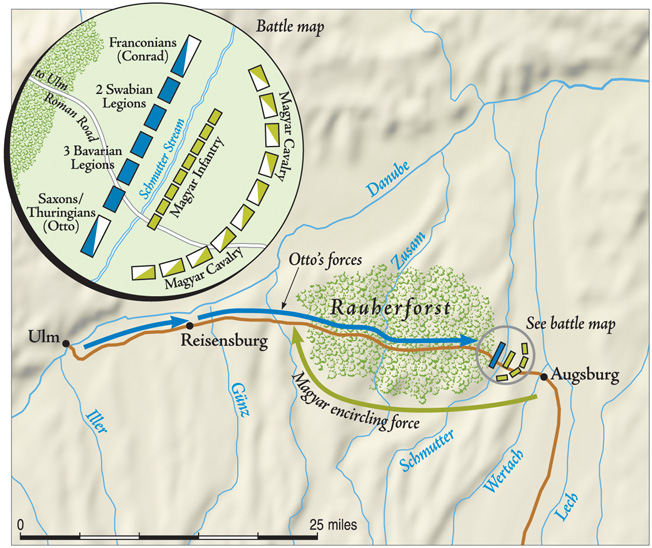

In early August, after the Magyars had pulled back to Lechfeld plain below Augsburg, Otto’s scouts discerned that Augsburg was the Magyars’ real objective, and that the main body of the enemy force intended to seek battle with Otto’s relief army on the Lechfeld. By that time, Otto had 8,000 men under his command organized into eight legions: three from Bavaria, two from Swabia, one from Franconia, one from Bohemia, and his own drawn from Saxony and Thuringia. The German army comprised both infantry spearmen and mailed knights armed with swords and lances. The Franconian legion consisted almost entirely of veteran heavy cavalry led by Conrad the Red, who had agreed to support Otto in future campaigns.

The lead Bohemian legion stumbled into Otto’s forward base at Ulm on August 7 after conducting a forced march. The crack troops were exhausted from their long trek, and Otto assigned them to march at the rear of the relief column. He also ordered their commander to closely guard the relief army’s supply train. A second Bohemian division, which had farther to march, halted at Regensburg upon learning the German king had left Ulm for Augsburg.

Marching Through the Woods

The cities of Ulm, Donauworth, and Augsburg formed a triangle of sorts on the border between Swabia and Bavaria. Ulm was situated at the bottom left, Augsburg at the bottom right, and Donauworth at the top of the triangle. The Magyars hoped that Otto would march northeast from Ulm to Donauworth and then turn south to Augsburg. If the German king took this route of march, the Magyars were confident they could overwhelm the relief army on the open terrain of the Lechfeld.

But Otto had crafted a plan designed to foil the Magyars and lessen their chance of defeating the Germans. Instead of proceeding to Donauworth, he crossed to the south bank of the Danube on August 8 and led his army east along the old Roman road that connected Ulm to Augsburg via Reisensburg. The long German column reached Reisensburg at the end of the day and camped just beyond the town, having marched about 15 miles. The next day the army continued east to Horgau, where it encamped for the night. Horgau was situated on the western edge of a thick wood known as the Rauherforst. At that point, the Germans were within a day’s march of Augsburg. Otto planned to march his army on the narrow Roman road through the Rauherforst and assess the tactical situation once he emerged from the forest the following day. Otto believed the dense woods would protect his men from hit-and-run attacks by the Magyars until he was close enough to Augsburg to force them into a close-quarters battle with his more heavily armed force. Although not without its share of risks, it was a much safer route than advancing unprotected on a long march south from Donauworth through the Lechfeld.

First Attack on Augsburg

When the Magyar main army with light cavalry, infantry, and siege weapons arrived before Augsburg sometime in late July, it camped on the east bank of the Lech, three miles southeast of Bishop Ulrich’s city. The Magyar chieftains chose the site because they believed it would be safe from any large-scale sortie that Ulrich might launch from the city in an effort to overrun their base camp. Ulrich had a substantial number of local professional troops inside the city, and it is conceivable that he might have been able to achieve this if the Magyars had camped beneath the city’s walls.

The Magyar main army encountered little resistance on its advance from the Enns. Once word spread of another barbarian invasion, many villagers and local forces east of Augsburg sought safety in local fortresses or cities in eastern Bavaria such as Salzburg, Passau, Freising, and Regensburg. Bent on the capture of Augsburg, the Magyar vanguard and main body bypassed the other cities and local strongholds. By doing so, they allowed local forces to quickly regain control of the primary roads and river crossings once the Magyars had passed. If the battle went against the Magyars, they would likely meet substantial resistance and pay a heavy price attempting to get back to the Carpathian Basin by the same route they had traveled to Augsburg. It was a risk of which the Magyar chieftains were probably aware, but they had no other recourse under the circumstances. It made a Magyar victory over Otto’s army essential if the barbarians wanted to continue their semi-nomadic lifestyle, which was dependent on wealth accumulated through captured prisoners and stolen treasure.

Once the Magyar main army arrived before Augsburg, it did something completely unexpected. After establishing their camp, on August 8 a small force of Magyars attacked the city’s most formidable gate. Correctly guessing that the east gate high above the Lech likely was less well defended than the other entrances to the city, the Magyars hammered at the gate with siege weapons in an attempt to gain a quick foothold inside the city. Bishop Ulrich, astride a majestic warhorse, led the Germans in a counterattack outside the city wall. The fighting raged for a time, but when the Germans killed the Magyar prince leading the attack, the enemy broke off and returned to their camp.

Ambushing the Bohemians

The following morning, the traitor Berthold arrived in the Magyar camp with news that Otto was marching west from Ulm with a relief army. In response, the Magyars turned their attention away from the siege and focused on destroying Otto’s relief army. The Magyars were so consumed with their desire to defeat Otto that they failed to leave behind even a token force to keep watch on the Augsburg garrison. As a result, Ulrich’s brother, Count Dietpald, led most of the city’s garrison away from the city to add their numbers to Otto’s army.

The Magyars adapted well to the shifting demands of the campaign and were able to devise a clever plan to ambush Otto’s relief army. The swiftest-moving bands of mounted archers would skirt the Rauherforst to the south and conceal themselves until Otto’s last legion had entered the woods. When the moment was right, the Magyar ambush party planned to attack the rear of the column and block a German retreat. On the other side of the forest, the Magyar main force stood poised to attack the German vanguard as it emerged from the west side. The plan was to catch the Germans as they tried to deploy from column to line of battle and prevent them from forming a battle line. Once that was accomplished, the Magyar main army would seal off the Roman road on the west. By that time, the Germans remaining in the woods would discover that they were trapped and make a panicked attempt to exit the east side of the Rauherforst. At that point, they would be cut down by Magyar troops waiting for them to exit.

The Magyars broke camp on the afternoon of August 9 to take up their respective positions and await the passage of Otto’s army through the Rauherforst. The ambush party rode five miles west from their main camp to a new position south of where the road from Ulm to Augsburg entered the Rauherforst. The ride consumed a good portion of the day as it involved crossing the Lech and Wertach Rivers. Once they arrived at their destination, the ambushers concealed themselves in folds of the landscape and slept next to their mounts on the night of August 9. Their plan for the following morning was to wait until only a single legion at the back of the German column remained in the open. At that point, the mounted bowmen would surround the German rear guard and fire arrows into it from a safe distance. If the legions already inside the forest returned to rescue their fellow soldiers, the Magyars would pick them off too.

As the sun arced slowly across the sky on the morning of August 10, the Magyars waited tensely for the Germans to begin their journey through the Rauherforst. The barbarians west of the forest shifted restlessly in their saddles as they waited or the most opportune moment to attack. The Germans had risen early and had begun tramping east under a scorching sun toward the dense forest. By mid-morning, the vanguard and main body of the German army had disappeared inside the Rauherforst. At that point, the ambushers divided into small bands and began encircling the Bohemians, cutting them off from the Swabians in front of them. The Bohemians ran for cover to escape thick showers of arrows that rained down on them. The advantage was clearly with the Magyars, and the destruction of the Bohemians was swift and efficient. Although a large number of men from the Swabian legion adjacent to the Bohemians tried to reinforce them, they were cut down before they could alter the outcome of the ambush.

[text_ad]

It took less than an hour for the ambush party to overwhelm the Bohemians. Most of the Bohemians were killed, but a small number were taken prisoner and the victorious Magyars began sifting through the baggage train for loot that they could carry off. Believing that the feeble attempt of the Swabians was the last they would see of the Germans for the time being, they left the west entrance to the forest unguarded and focused their attention on the treasure that had fallen into their hands. This lack of discipline, something that would likely never have occurred under their more disciplined ancestors, would prove to be a serious blunder.

Franconian Revenge

As the ambush party was rifling through the contents of Otto’s supply train at midday, the German vanguard was exiting the Rauherforst on the east side and forming for battle outside the village of Ottmarshausen, a short distance from Augsburg. A messenger brought word of the destruction of the rear guard to the king. Otto and Conrad, who were side by side issuing orders in preparation for battle with the main Magyar army, stopped what they were doing and listened intently to the messenger. The king and his son-in-law conferred briefly. Otto told Conrad that once the vanguard and main body had exited the woods and the road was clear, Conrad should take his mounted legion of Franconians and ride back through the forest to the west side. Once there, he was to rally the remnants of the Swabian legions and counterattack the Magyars.

By mid-afternoon, Conrad had ridden back through the forest, rallied the Swabians, and launched a counterattack on the disorganized Magyar ambush party. The Magyars fled at the first glimpse of Conrad’s heavy cavalry galloping toward them. A large number were slain by the revenge-hungry Franconians. Infuriated by the cunning nature of the Magyars, the Franconians overran the Magyar position, hacking down many before they could escape. Once the Magyars were driven off, Conrad ordered his men to round up a small number of prisoners, secure what remained of the ransacked provisions, and prepare to countermarch to rejoin Otto’s army.

Waiting For the German Attack

As Otto’s troops passed from the forest to the open ground, they were exposed to the searing midday sun. Less than a mile away, on high ground on the far side of a small stream known as the Schmutter, the Magyar main army drew up in its classic crescent formation. They had chosen their ground well, and their formation was designed to allow them to bring maximum firepower on an attacking enemy. In the center, the Magyar chieftains had placed their lowly infantry as bait with which they hoped to entice the German heavy cavalry to charge. If the German cavalry was foolhardy enough to do so, the Magyars planned to close in on them from all sides until they were completely encircled. The mounted bowmen would then fire volleys of arrows high into the sky that would plummet downward with a force capable of piercing any armor.

The Magyar chieftains decided at the last minute to await the German attack rather than try to destroy Otto’s troops before they could deploy. By waiting, they had less to lose than the German king. The Magyars had a larger army, which was better supplied than the German army. Therefore, the burden was on Otto to press the attack because he could not afford to wait. Otto wasted no time preparing for battle. The German king arrayed his troops, then gave them a rousing speech designed to motivate them to perform great feats against a numerically superior foe.

Otto placed Conrad’s cavalry, which was exhausted from its defeat of the Magyar ambushers, on the left flank, where it was protected by the cliff wall. In the center, Otto deployed the remnants of the two Swabian and three Bavarian legions, which totaled about 4,000 spearmen. The far right flank was held by the crack cavalry of Otto’s combined Saxon-Thuringian legion.

The German infantry, as the Magyars had hoped, would lead the attack. However, Otto also planned to launch his cavalry simultaneously against the Magyar left flank. The success of the attack would not depend on the infantry alone. Otto instructed Conrad to remain out of range of the Magyars’ arrows, making just enough of a demonstration against their right flank to convince them that he might charge any minute. This would stretch the enemy line and pin down the Magyar right flank so it could not shift forces to support the center or left flank. The two flanking attacks by German cavalry—Conrad’s feigned attack and Otto’s real one—were designed to flatten out the horns of the crescent into a straight battle line. Otto believed this would foil the Magyars’ battle plan and prevent them from encircling and destroying the German center.

The Battle of Lechfeld

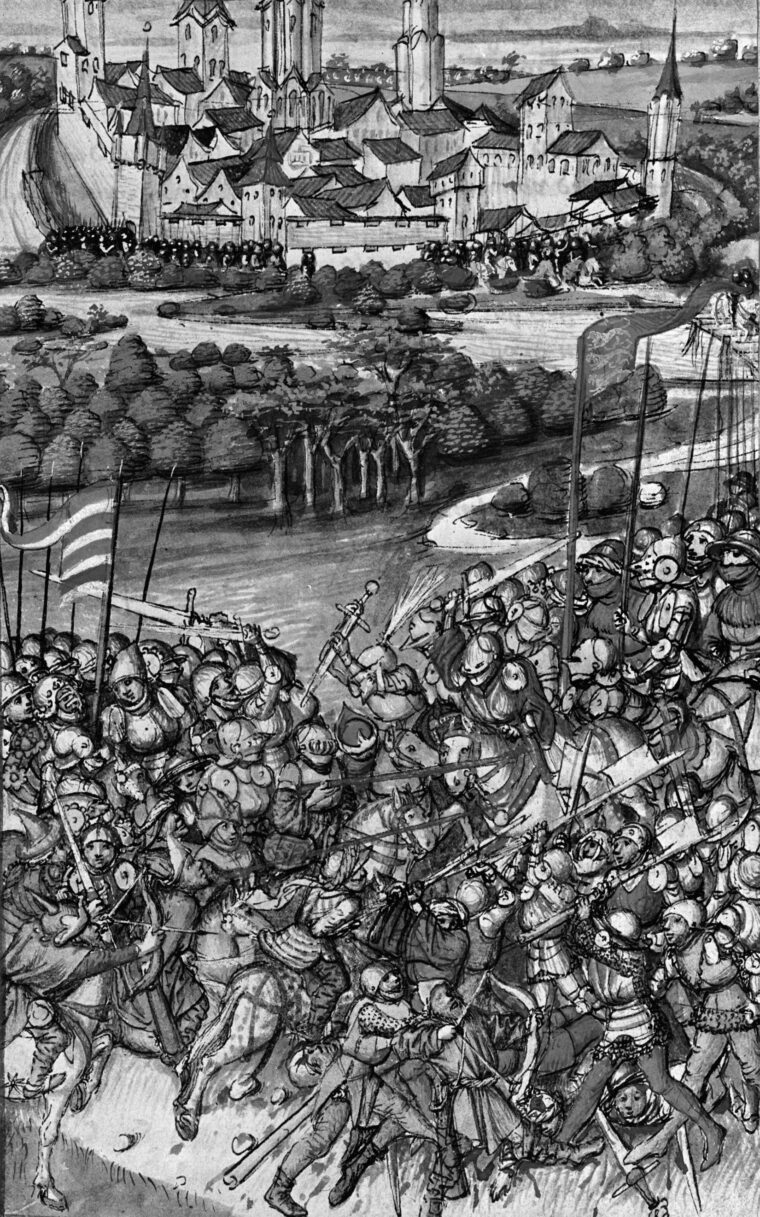

When the heat of the day was at its most intense in the mid-afternoon, the German heavy infantry advanced in a tight formation toward the less-experienced Magyar infantry. When the melee began, the Germans were able in a matter of minutes to slay large numbers of the enemy infantry; the survivors melted away. Fearful of a direct attack by German cavalry on either flank, the mounted bowmen refused to come to the aid of the infantry.

Once the infantry advanced, Otto waved forward his legion of mounted heavy cavalry. The ground shook as the fresh legion of Saxon and Thuringian horsemen galloped toward the Magyar left flank. The Magyar horsemen launched a volley of arrows, then turned and fled east. Conrad, on the opposite flank, having seen the enemy left and center give way, ordered his Franconian heavy cavalry to complete the rout of the Magyar army. With the same élan they had showed routing the enemy ambush party, the Franconians pursued and hacked down as many of the enemy riders as they could reach. The horsemen on the Magyar right flank had no place to escape. Otto’s cavalry, having dispersed the enemy left flank, had circled around behind them and stood ready to cut them off as they tried to break off contact.

A fearful slaughter occurred beneath the frowning cliff that overlooked the Magyar right, where their horsemen were trapped between two large groups of German cavalry. Elsewhere, the survivors of the Magyar center and right flank fled for their lives with the Germans in close pursuit. The hapless Magyar infantrymen, who had been forced against their will to participate in the campaign, had no chance to escape the Germans. They sought refuge in nearby barns or farmhouses, only to be burned alive when the Germans hunted them down and torched the buildings.

The German cavalry that had overwhelmed the Magyar right flank in less than two hours found themselves in possession of a landscape blanketed by large number of dead from both sides that testified to the ferocity of the fighting and an unwillingness to take prisoners. Unfortunately for the Germans, as the fighting ebbed on the battlefield and the blood of both sides turned the waters of the Schmutter an eerie red, a single Magyar archer inflicted a deep wound on the German psyche. After leading his men in a victorious charge, Conrad had unhooked the buckles on his armor to get some relief from the heat. Not long after, a retreating Magyar bowman took one last shot at the victors. The arrow he fired arced through the sky and struck Conrad in the throat, killing him instantly. It was a crushing blow to his fellow soldiers, many of whom had fought with him for years.

The Magyar cavalry that had been fortunate enough to have been posted on the left flank managed to escape when Otto swung north into the rear of the enemy army rather than pursue them east. Those horsemen withdrew in good order, regrouped a short distance away, and rode a few miles east, keeping their formation in the hope that the German cavalry would give chase. But Otto was too wise to fall for their familiar tactic of feigned retreat. He eventually rode east with his men as far as the Lech, then broke off pursuit at that point.

Pursuing the Magyars

A severe thunderstorm passed through the region that evening. The following day the Alpine rivers rose considerably in height. As a result, the major right-bank tributaries to the Danube—the Lech, Isar, Inn, and Enns—and their respective tributaries became treacherous to cross.

On the morning of August 11, the day after the hard-fought battle, Otto sent mounted messengers to local forces east of the Lech, informing them that the Magyars were in full retreat. He ordered them to do everything within their power to kill the marauders so that they would not return the following year. Otto also sent messengers to Duke Boleslav, leading a second Bohemian legion encamped at Regensburg, and to the leading nobles of Carinthia, which had been under Otto’s control since 952, appealing to them to intercept the retreating Magyars and destroy them. Boleslav immediately ferried his forces across the Danube and marched toward the city of Freising in the Isar valley, while a Carinthian force east of Freising, at Salzburg, prepared to block Magyar forces attempting to cross the Inn.

[text_ad]

Between the right tributaries to the Danube and the smaller rivers that fed them, the Magyar bands retreating to their base in the Carpathian Basin had to contend with as many as a dozen river crossings on their retreat. They found these crossings protected by not only Bohemian and Carinthian forces, but also by mixes of Bavarian professional and militia forces situated at nine major fortresses throughout central and eastern Bavaria.

The heavy downpour on the night of August 10 spelled doom for the retreating Magyars. The next afternoon a large body of Magyars forded the Amper near the Bavarian fortress of Sunderburg and pressed east toward a major ford on the Isar, a mile south of Freising. Just before dusk, the Magyars reached the ford and attempted to negotiate the river. As the Isar approaches Freising, it narrows between steep embankments that channel its waters and increase the speed of the river’s current. The long column of mounted bowmen waiting to ford the Isar was assailed by forces from Sunderburg and Freising, supplemented by fast-arriving Bohemians.

The barbarian troops were weary from the long, hard ride necessary to distance themselves from the German heavy cavalry. The troops in the front of the column unsuccessfully tried to ford the river; many were swept downstream to their deaths. Even many of those who managed to gain the far embankment tumbled back into the water and drowned. Other Magyars trying to commandeer ferryboats to get across wide or treacherous rivers discovered that local boatmen loyal to Otto were not receptive to being bribed. Many of the desperate Magyar horsemen were cut down or pitched into the water by those manning the ships.

The Bavarians and their allies took no prisoners except for the most exalted of Magyar princes and chiefs, who were rounded up and taken to Regensburg. Within a few days the noble prisoners, including chiefs Lel and Bulcsu, were hanged on the gallows alongside many of their less-exalted compatriots. A pitiful remnant of the Magyar army escaped to the Carpathian basin, but the majority were killed. As for Otto’s army, it lost upward of 3,000 killed. Across Europe, Otto’s triumph over the Magyars was favorably compared to Charles Martel’s victory over the Spanish Muslims at the Battle of Tours in ad 732.

Otto as Holy Roman Emperor

After the destruction of the retreating barbarian army, one of the first measures Otto undertook upon returning to Magdeburg was to distribute lands and titles to the Bavarian and Carinthian nobles who had assisted him in his hour of need. After that, he resumed his ongoing war with the Transelben Slavs. In October of the same year, Otto won a decisive victory over the Slavs at Recknitz. The pair of great victories over the pagan eastern peoples made possible the further spread of Christianity into regions that hitherto had remained outside of its grip. In 962, a grateful Pope John XII crowned Otto as Holy Roman Emperor in a ceremony at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The act united the kingdoms of Germany and Italy into the newly constituted Holy Roman Empire.

The Magyar defeat in 955 laid the groundwork for major political and religious changes in the years to follow for the peoples of the Carpathian basin. No longer would the Magyars, living a semi-nomadic lifestyle on the steppes, hold sway over the region. The German victory at Lechfeld signaled the military and political end of the Magyar menace. The Magyars lost so many veterans in the 955 campaign that few survived to train the next generation in the art of nomadic warfare, which reduced the Magyars to the ranks of second-rate warriors. By the end of the millennium, under King Stephen I, the principality of Hungary had become the Kingdom of Hungary and the majority of its people had embraced Christianity, signaling the ultimate end of the Magyars and their barbarian ways.

Very interesting account!

What did Otto I. do with all his fallen soldiers in the battle of Lenchfeld? Did they leave them there and return to Megdeburg?