By Robert L. Durham

In the fall of 1862, Confederate armies were making their first and only coordinated effort to carry the war into the North. In the east, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had won the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 30, threatening Washington, D.C., as he began his Maryland campaign. By September 15, Gen. Stonewall Jackson had captured the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Then Lee ordered Jackson to join him in Maryland at Sharpsburg, where his force of 45,000 would make a stand behind Antietam Creek as Union Gen. George B. McClellan approached from the east with 87,000 men.

A day earlier in the western theater, General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Mississippi marched into Glasgow, Kentucky, with an eye on crossing the Ohio River at Cincinnati. Bragg had brought 20,000 rifles with him hoping to find sympathetic Kentuckians eager to join him in fighting Union Gen. Don Carlos Buell and to help with the capture of Louisville. Bragg had never had plans to capture Cincinnati, but the threat had stirred up Ohio troops eager to defend it.

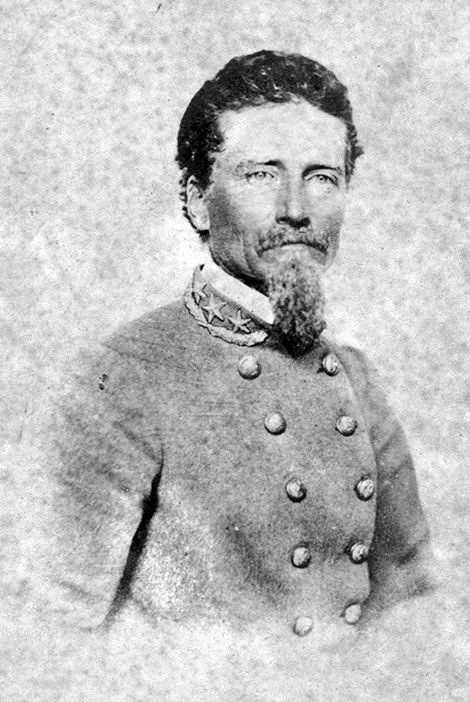

While the exploits of Bragg and Lee played out on the national stage, two armies in Northern Mississippi—the Army of the West under Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, and the Army of West Tennessee under Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, were tasked with keeping Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and other Union forces in lower Tennessee by combining their armies and attacking the vital southern town of Corinth, Mississippi.

Overshadowed by the horrific scale and violence of the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, the strategic significance of Corinth lay in its railroad junction, the crossing of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, and the Memphis and Charleston Railroads. Corinth had been Grant’s target when Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, knowing he was outnumbered, had marched 19 miles north to surprise him at Shiloh.

After defeat at Shiloh, General P.G.T. Beauregard ordered his troops to fall back and fortify Corinth. Beauregard was now in command following Johnston’s death at Shiloh on April 6.

Major General Henry Halleck, commander of the Union’s Department of the Mississippi, was unimpressed with Grant being caught by surprise at Shiloh. He took over command of Union forces and followed Beauregard toward the town described as the “vertebrae of the Confederacy” by former Confederate Secretary of War LeRoy Pope Walker.

Halleck, himself, considered Richmond, Virginia, and Corinth to be the “great strategic points of the war, and our success at these points should be insured at all hazards.”

Halleck was cautious by nature and the historic carnage at Shiloh—some 20,000 combined killed and wounded—caused him to move even more slowly. Fortifying after each advance, Halleck at one point had only moved five miles in three weeks. Finally, on May 27, 1862, the siege guns were in place and the Union began to bombard Corinth.

By this time, Confederate morale was extremely low. Outnumbered two to one, they had lost almost as many men as they had at Shiloh to typhoid and dysentery. On the night of May 29, they withdrew from Corinth to Tupelo, Mississippi, about 50 miles south.

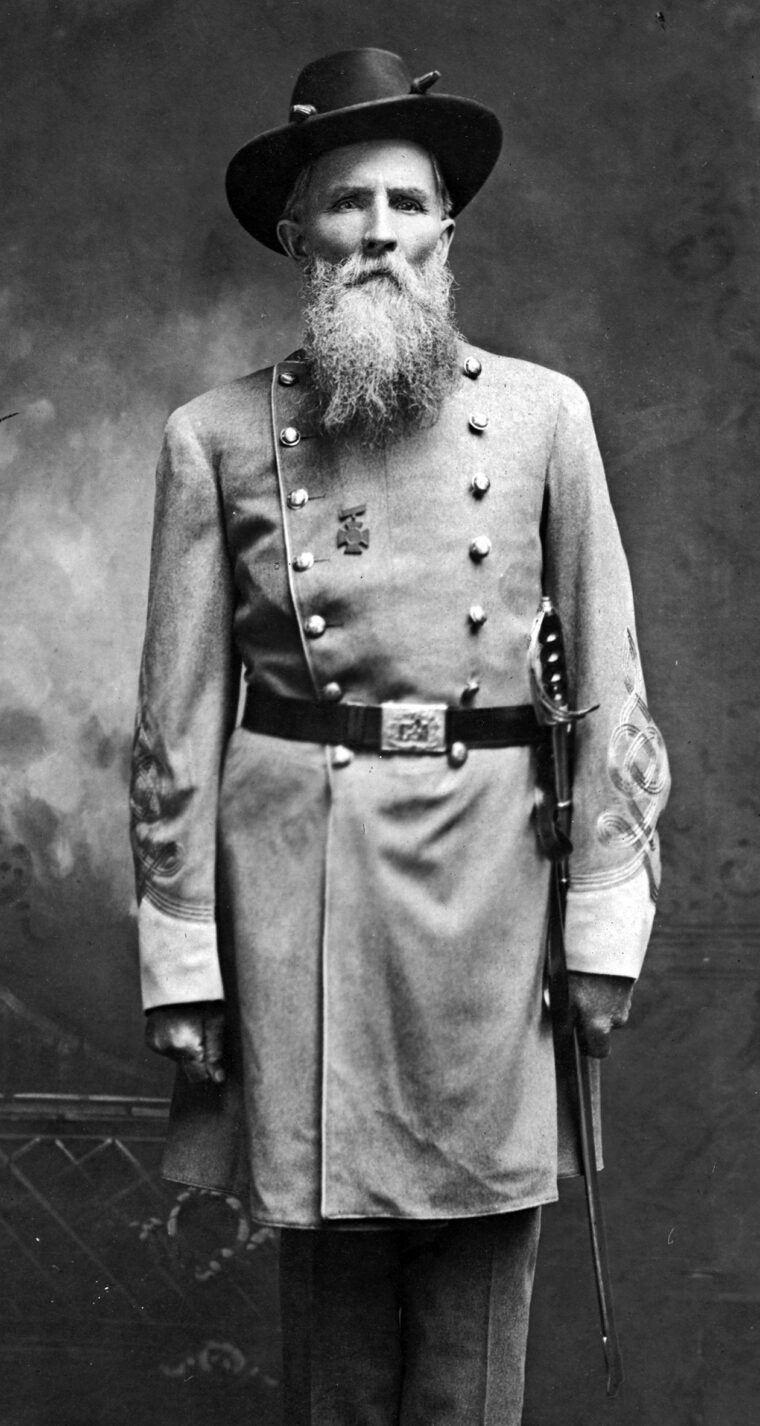

Following the retreat from Corinth, Beauregard took a medical leave of absence without permission, leaving newly promoted Gen. Braxton Bragg in charge. The relationship between Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Beauregard had already been strained for some time, so Davis gave the command of the Army of the Mississippi (renamed Army of Tennessee in November) to Bragg and transferred Beauregard to Charleston, South Carolina.

Van Dorn was given command of the Department of Southern Mississippi and East Louisiana on June 28 and went to Vicksburg to improve the Confederate defenses there. Union gunboats were threatening the city from upstream and down. Van Dorn raised the morale of the 4,000 troops garrisoned there, setting up cavalry patrols and ordering the construction of new field works.

At the beginning of July, Bragg was still in Tupelo and making preparations to try to retake Corinth when he got word on July 10, that Buell’s Army of the Ohio was moving toward Chattanooga with 30,000 troops. Another cautious commander who insisted on preparation, Buell’s progress was delayed by repair work on railroads and bored troops looting the countryside. At times during that summer, his army was making barely a mile per day.

As Bragg saw it, Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Chattanooga, Tennessee, were the keys to holding onto and regaining control of the western theater. Knowing Buell was headed for Chattanooga, Bragg would finally answer the call for reinforcements from Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Department of East Tennessee. Union Brig. Gen. George Morgan’s 7th Division of the Army of the Ohio had occupied Cumberland Gap since the middle of June, threatening Smith at Knoxville, Tennessee.

Price, who remained in Tupelo with his Army of the West, was left in command of the District of Tennessee.

With the Union holding Memphis and much of western Tennessee, Bragg and his infantry had to travel 766 miles by train—from Tupelo to Mobile and Montgomery in Alabama, then to Atlanta and Dalton in Georgia—to get to Chattanooga. The cavalry and artillery went by road. Bragg arrived at Chattanooga by July 30, ahead of Buell, who went to Nashville instead.

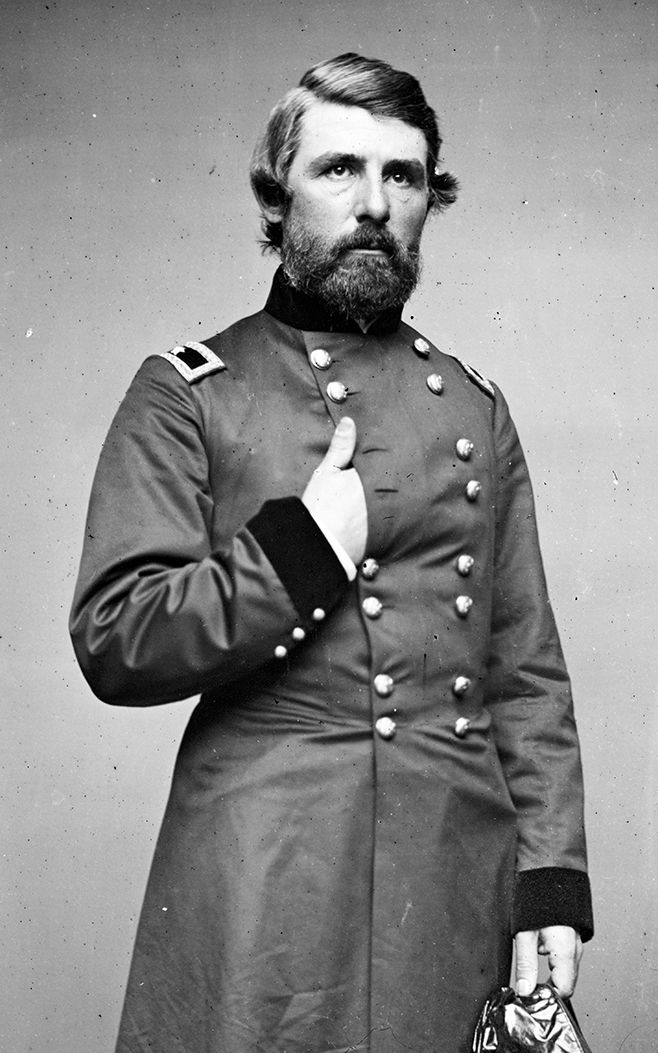

Bragg, having been convinced by Smith to invade Kentucky before driving Union forces out of Tennessee, was in the Bluegrass State in early September when he urged Price and Van Dorn to attack Corinth to keep Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Mississippi there from reinforcing Buell. If successful, Bragg hoped they could then march north to join him.

On September 13, Price arrived at Iuka, Mississippi, a small Union supply depot on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. After some cavalry skirmishing, the Federal commander at the post, Col. Robert C. Murphy, set his supplies afire, and fled to Corinth. The Confederates put out the fires and saved most of the much-needed provisions. Murphy was later court-martialed for failing to destroy the supplies, but was acquitted. Price settled down in Iuka to wait for Van Dorn, whose 7,000 men would bring the combined strength of the two armies to 22,000.

As the district commander, Grant sent Rosecrans to retrieve the situation, and to recapture Iuka. After an intense, bloody battle, Price retreated to Baldwyn, Mississippi, on September 19, the same day Lee crossed the Potomac back into Virginia following Antietam.

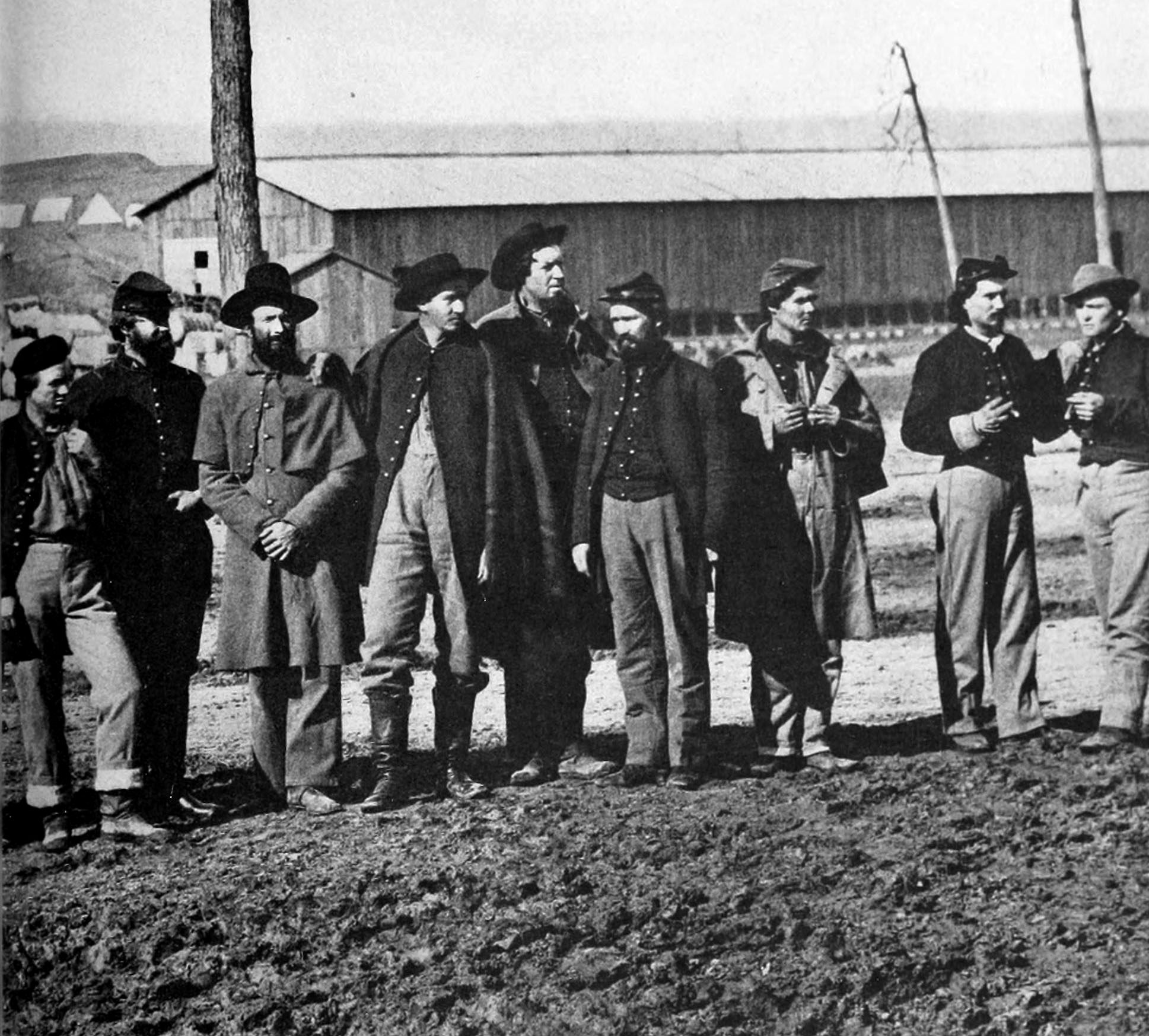

Price learned from his Iuka experience that the Federals could concentrate enough forces rapidly anywhere between Iuka and Memphis, to crush either his or Van Dorn’s commands individually. Price believed they had to join forces and he sent a notification to Van Dorn, saying “I will leave here in two days to form a junction with you.” They met at Ripley, Mississippi, with Van Dorn, the senior in rank, taking command. This did not sit well with Price but, for the good of the cause, he readily conceded.

Van Dorn reasoned that an attack on Memphis would not yield a military advantage as Union gunboats would make holding the city impossible. The fortifications around Bolivar, Tennessee, made a quick assault there unfeasible—and Union reinforcements could be quickly sent there by railroad from Jackson, Tennessee. In addition, both flanks would be exposed to Federal attacks from Memphis or Corinth.

At an interview with Van Dorn on the 18th, Van Dorn told Price he would attack the Union army at Corinth before starting for Nashville. The capture of Corinth would force the Yankees to abandon West Tennessee, enabling Van Dorn and Price to move north to join Bragg with no interference from the Federal army.

Capturing Corinth would cut off Bolivar, Tennessee, and then Jackson, Tennessee, would easily fall. He was expecting paroled prisoners of war from Fort Donelson to reach him soon and, with those added soldiers, he would control West Tennessee. This would enable him to advance through Middle Tennessee to join Bragg’s army. “The attack on Corinth was a military necessity requiring prompt and vigorous action,” Van Dorn wrote.

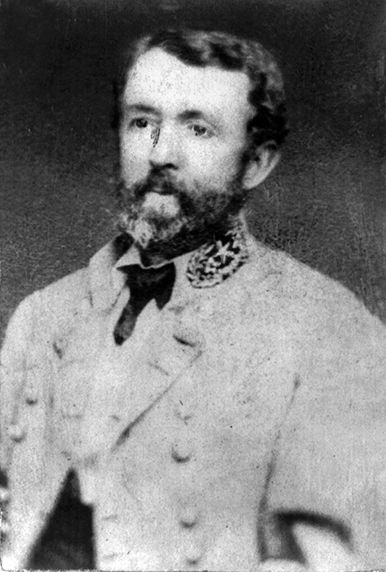

But not all of his generals agreed. Major General Mansfield Lovell, now commanding Van Dorn’s Army of West Tennessee, favored an attack on Bolivar. However, he thought if the Confederates could take Corinth, the Federals must fall back to Jackson, Tennessee and, “finally (if we get our additional forces from the returned prisoners) we shall be able to drive him to the Ohio.”

Price agreed on the necessity of taking Corinth but wanted to wait for the return of the prisoners, now being organized in Jackson, Mississippi. He expected that the 12,000 to 15,000 new soldiers would make them strong enough to take it easily.

Van Dorn dismissed the objections of Lovell and Price and ordered them to distribute three days’ cooked rations and be ready to move the next morning. Lovell would lead on September 29, followed by Price the next day. They first headed north in a feint on West Tennessee.

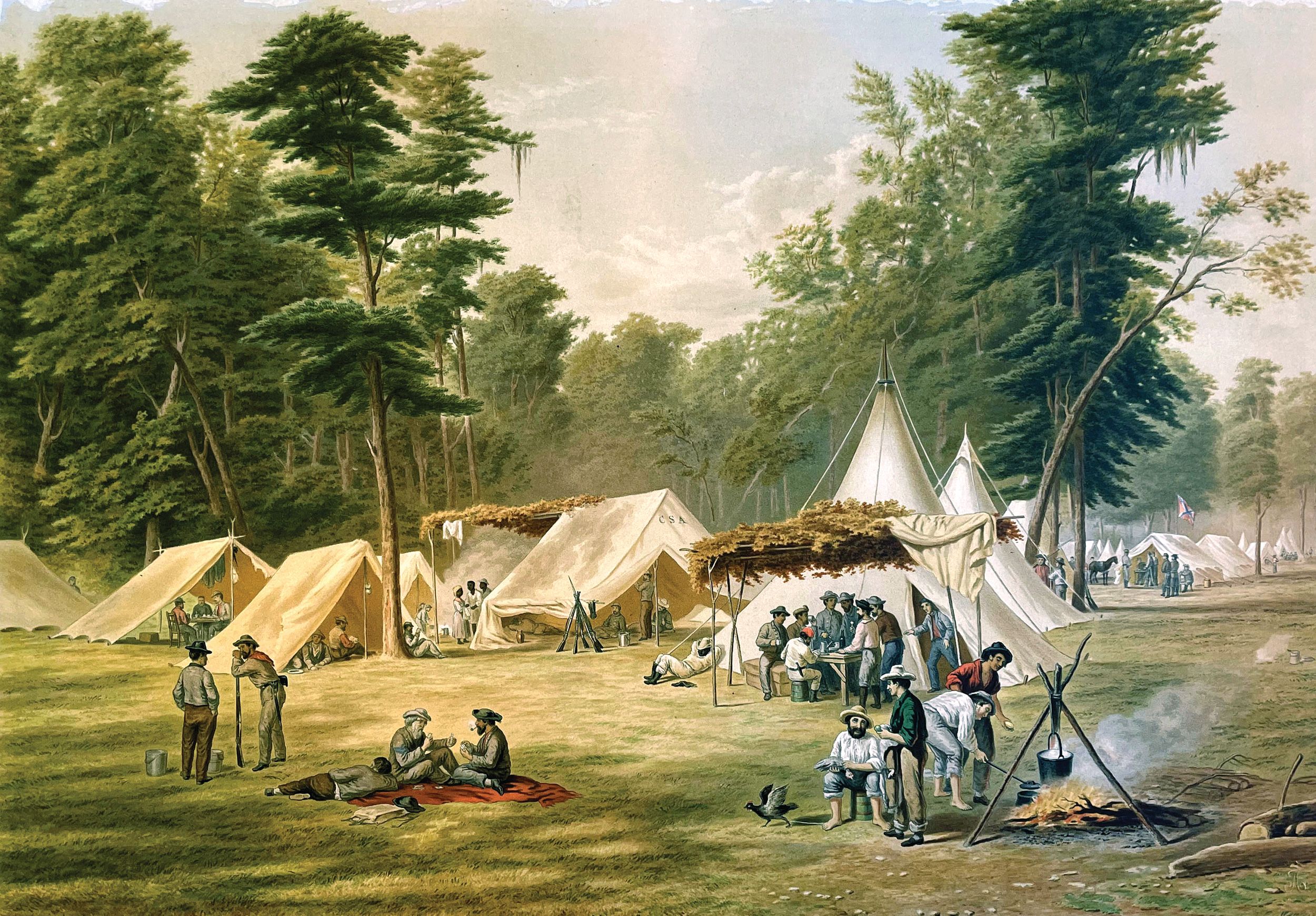

October 1 was unseasonably warm with temperatures above 90 degrees. Most of the streams had dried up, making water hard to find. Many of the Rebel soldiers fell out of ranks to straggle in later, and some suffered sunstroke. None of the regimental officers and men knew the objective of their march. Price’s men were delighted when they crossed the line into Tennessee. They “wanted to go north” and they found the possibility of returning to Mississippi repulsive.

As they then turned east along the Tennessee-Mississippi border, they found that Yankee cavalry had torn up and burned the planking on the Davis Bridge over the Hatchie River. After replanking the bridge, they continued to Chewalla, Tennessee, where they bivouacked on October 2, only 10 miles northwest of Corinth.

“The men remembered the fortifications around this intrenched position, strengthened under the energetic labors of the enemy, and protected by heavy abattis of felled timber,” Sergeant William H. Tunnard, a soldier in the 3rd Louisiana later wrote. Many became despondent when they realized what their journey had in store.

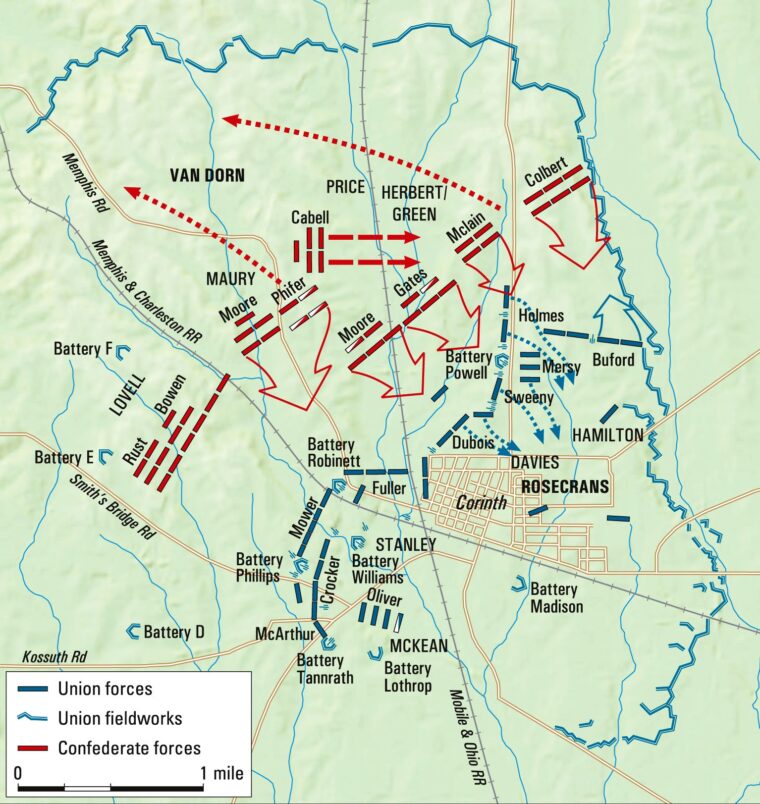

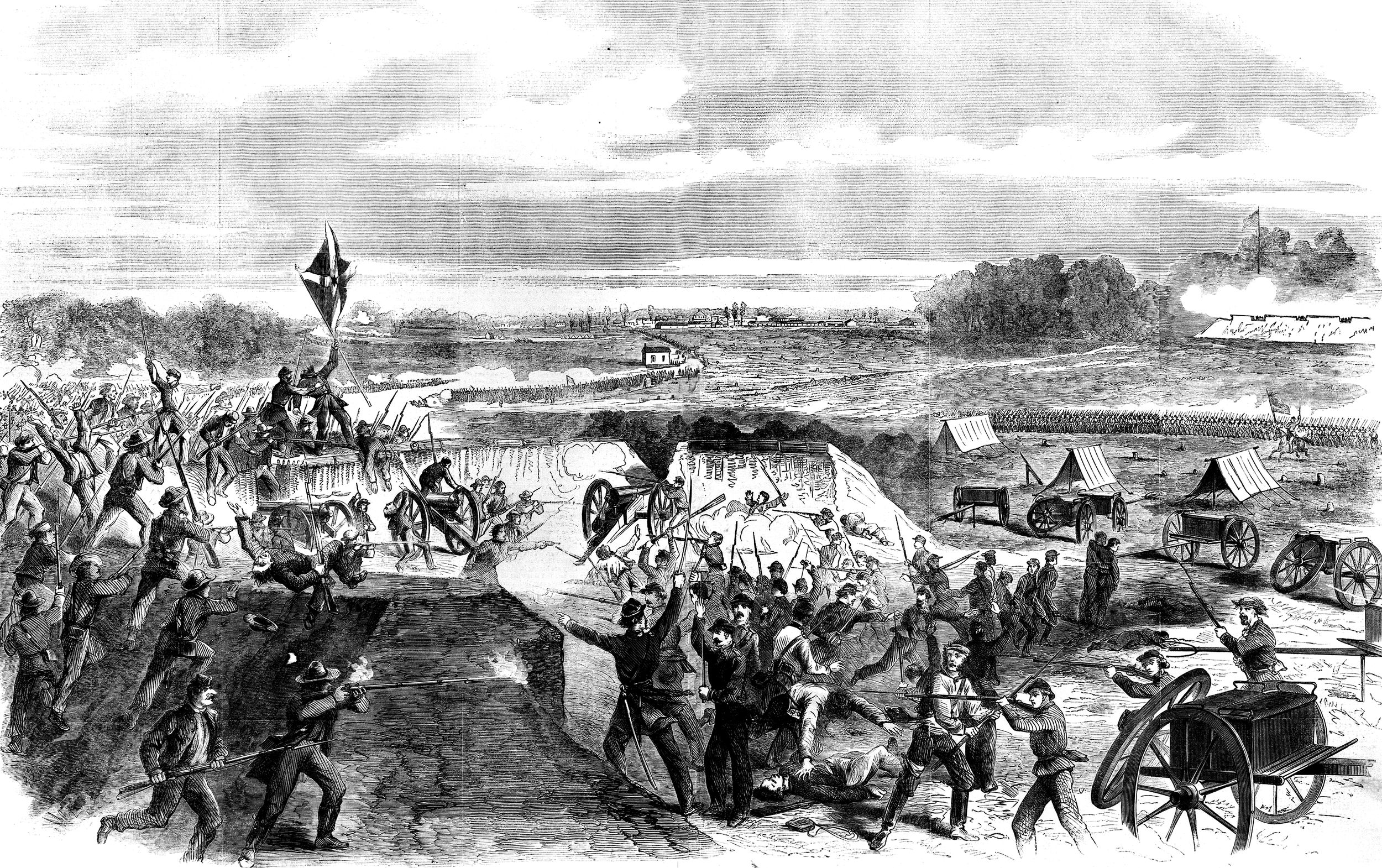

Grant also now knew the Confederate’s destination and sent word to Rosecrans to be prepared for an attack. Rosecrans had gone to Corinth on September 26 and initially had only 15,000 men in the town. He drew in 8,000 more from outposts in surrounding towns and immediately put his men to work strengthening the fortifications, which had been built by the Confederates under Beauregard the previous spring. Rosecrans commanded the battery lunettes to be connected by breastworks. Rosecrans ordered “the front to the west and north to be covered by such an abatis as the remaining timber on the ground could furnish.” He “employed colored engineer troops organized into squads of twenty-five each” to work alongside the soldiers. His final contribution to the defenses consisted of having a new redoubt, Battery Powell, constructed a half mile north of town. This battery accommodated six guns.

The morning of October 1, Rosecrans ordered Col. John Oliver’s brigade, of Brig. Gen.Thomas McKean’s Division, to Chewalla, to slow any Confederate advance. They found the march terrible, “The heat and dust and swift pace were too much for the men,” remembered a 47th Illinois soldier. “One by one the boys dropped out, unable to continue further.” When they went into camp at midnight, most of the men threw “themselves down in the furrows of an old corn field, too weary to build fires or seek refreshments.”

On October 2, at 10 a.m., the 7th Tennessee Cavalry charged a company of skirmishers from the 15th Michigan. They “drove in the enemy’s pickets,” recalled J. P. Young of the 7th. The 15th formed a line and attacked the Rebel cavalry, who dismounted to meet them but slowly gave way. Then the Michiganders retreated when they ran into Brig. Gen. Albert Rust’s brigade of Lovell’s division, in advance of the Southern army.

Oliver’s skirmishers faced their Southern counterparts the rest of the day with few casualties on either side. In the evening Rosecrans ordered Oliver to make a fighting withdrawal to the outer defense fortifications northwest of Corinth.

Daybreak, October 3, found Van Dorn’s entire Confederate army arranged in sight of the outer Corinth earthworks, with no reserve. This day would be another murderously hot one, with the temperature already above 90 degrees. At 9:30 a.m., Van Dorn called a final meeting with his generals and, at 10 a.m., he launched the attack, in an echelon from right to left.

General Lovell’s division came in first; thick timber split his command. McKean’s Federal division stood ready to face them. The Union 21st Missouri held the extreme left of the Federal defenders, in an isolated position. Alabama, Arkansas, and Kentucky troops of Rust’s Brigade temporarily drove them back. Col. David Moore tried to rally the 21st Missouri’s Union soldiers. “About this time my horse was shot under me, bruising severely my amputated leg,” Rust reported [Rust had lost his leg at the Battle of Shiloh]. As his men carried him from the field, he turned the command over to Maj. Edwin Moore, “who rallied the men and repeatedly drove the enemy from the hill.” Finally, flanked on both sides, the blue-clad soldiers fell back.

Rust’s men moved past the Missourians’ right flank to the edge of the hill. A deadly fire came into Rust’s left flank from the other side of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The 4th Alabama, assigned as skirmishers in front of the brigade “fled in wild confusion.” The left and center of Rust’s Brigade charged against the Federal artillery and infantry, as close as 60 yards. The artillery switched from shell to solid shot. One shot “struck a large tree, just a few feet from my head and tore it to pieces,” remembered Private W. G. Whitfield of the 35th Alabama.

Rust’s Brigade had come up against the 57th Illinois and a section of Battery D, 1st Missouri Light Artillery. The Rebels came on a second time “with that cold-blooded yell which has to be heard to be appreciated,” said one Illinoisan. For a third time, they charged, “Our men stood the shock nobly, delivering the most steady and effective fire I have seen during the war,” stated Captain James Zearing of the 57th. Rust’s men attacked resolutely against this intense barrage. The fire from the 57th Illinois increased “but it had no effect in checking their march. They advanced on the double-quick in the utmost disregard of human life.”

The 9th Arkansas and 35th Alabama charged the Union battery section, which tried to get away. One made it, racing off to safety. The limber pole on the other gun broke and the cannons smashed into the ground.

From behind the old Confederate earthworks, the other Union artillery continued to rain fire on the Rebels. A Mississippi sharpshooter battalion came forward in a skirmish line against three Federal guns when they “turned loose solid shot whose unearthly screams through the air set up the most gigantic dodging I have ever seen,” Capt. C.K. Caruthers, their commanding officer, related. “We swept away the enemy’s skirmishers, despite the huge limbs of trees cut off by the solid shot.” James Newton, one of the Yankee skirmishers being swept away, unashamedly described his flight, “I could not run so fast as I had ought on account of a sore foot.”

On the left of Bowen’s Mississippians and Missourians, Brig. Gen. John Villepigue, also of Lovell’s Division, brought his brigade up against the Federals. Greatly outnumbered, the Union line began to unravel. To finalize their plight, Brig. Gen. John Creed Moore’s Brigade, of Brig. Gen. Dabney H. Maury’s Division hit them hard, racing out of the woods to strike their right flank and rear.

General Lovell, pleased with his division, told the men of the 35th Alabama, “Well, boys, you did that handsomely.” He felt the work of his division to be finished. Rust had pushed forward 300 yards; Lovell had him return to their starting position. Bowen and Villepigue had lost control of most of their regiments and Lovell told them to reassemble their men and return to their original line. “We had captured the outer line, and… we remained there; not a regiment of the brigade or the division engaged,” said a disgruntled Lieutenant Holmes of Bowen’s Brigade.

The 7th Illinois, on the right, experienced the attack of Gen. Moore’s Brigade before any of the others. Col. Andrew Babcock, their commander, looked “to the rear; he looks down a ravine and beholds the Chewalla road swarming with rebels,” in the words of Sergeant D. Leib Ambrose. The Federals broke, fleeing before being cut off.

Colonel Marcellus Crocker’s Brigade of McKean’s Division stood in reserve behind the routed Federal infantry. “The Union troops fled in confusion toward us, the pickets and skirmishers nearby joining in the stampede. The enemy followed a short distance, firing and yelling like demons,” remembered Capt. Clinton H. Parkhurst of the 16th Iowa. “The fugitives poured into view like scattered sheep… scores of them being bloody from wounds.”

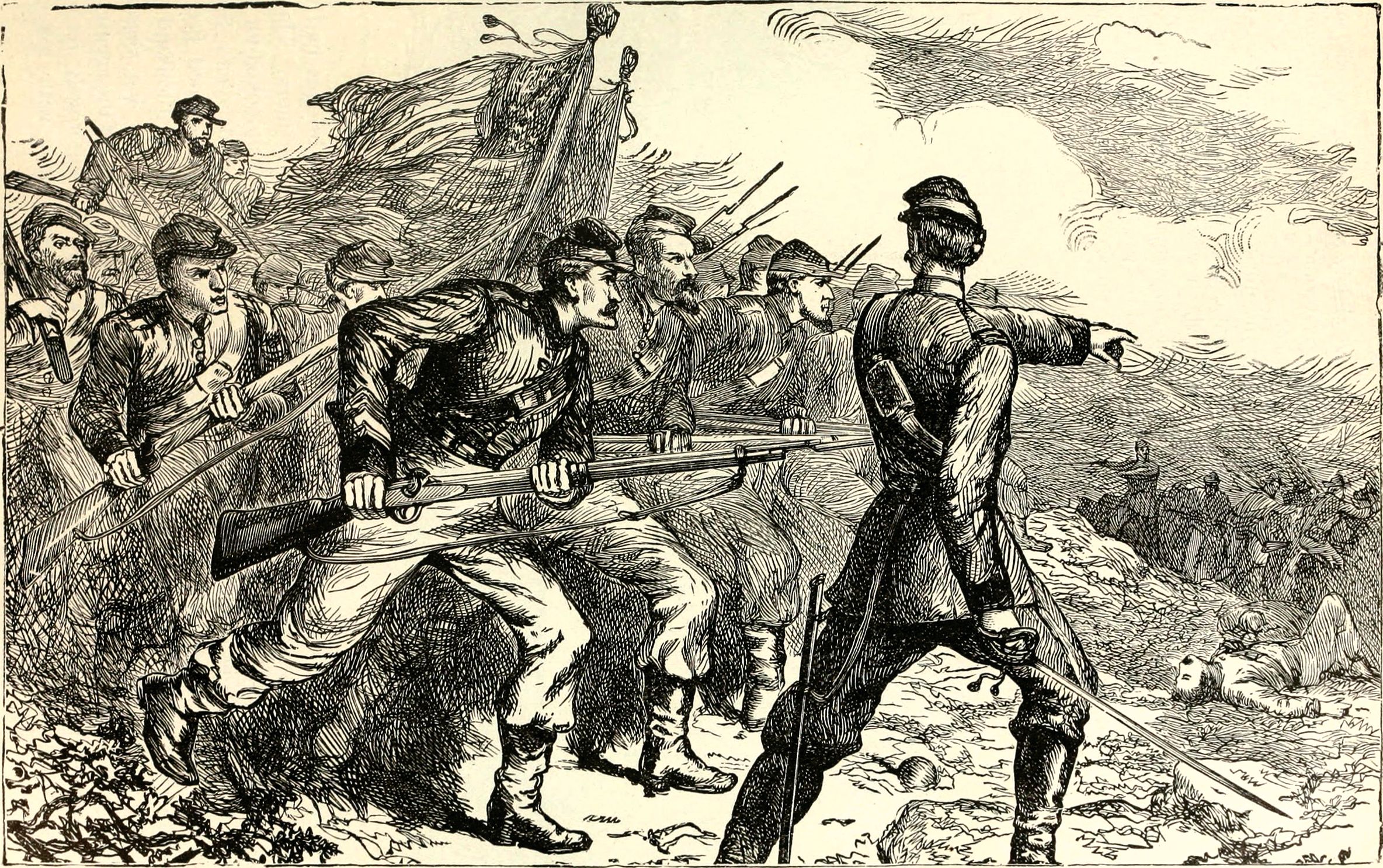

Two Confederate brigades “marched at common time, in perfect silence, preserving faultless lines,” wrote Parkhurst. “We took deliberate aim, and with a crash we fired… It was scarcely a moment before an answering volley hurled bullets among us… and the battle opened with fury…As we fought at remarkably short range, many of us rammed down two minie balls with each load of powder.” A pause occurred in the fighting and the Federal commander ordered them to retreat to Corinth.

In the center of the Union line, the men of Brig. Gen. Richard Oglesby’s Brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Davies’ Division, waited apprehensively for the next Confederate shoe to fall. They watched as six Rebel brigades assembled in the timber facing their line. “Through an opening in the woods I could see the rebels forming their lines for the assault on our works. The woods seemed to be full of the men in gray. A great number passed this opening; tramp, tramp, tramp, they kept coming,” remembered Corp. Charles Wright. Convinced the Union line should have been formed in the entrenchments closer to Corinth, “back a mile and more in our rear, under the guns of Robinett, was the place to make a fight,” he later remembered thinking.

The Rebel skirmish line alone comprised more troops than did all of Oglesby’s Brigade. The Confederates ran a battery onto a knoll in front of the 81st Ohio and opened fire. The Federal Battery H, 1st Missouri Light Artillery, opened a converging fire on the Reb battery, killing most of the battery’s horses and driving the battery to the rear. The Yankee infantry waited while Confederate Brig. Gen. Charles W. Pfifer’s Brigade bore down on them, and Col. John D. Martins’ Brigade made for a gap in the Federal line.

The Yankees had no choice but to flee as the Rebels burst over their breastworks. The 9th Texas Dismounted Cavalry captured a two-gun section of Union artillery. The other section escaped just in time, before being overrun. The Federal artillery and infantry fled to the safety of the breastworks near the town.

The way lay open for the Southerners to attack Corinth. However, Lovell, the commander of the only comparatively fresh Confederate division, thought his men had done enough. Not until 5 p.m., almost an hour after Brigadier General Moore had driven back Crocker’s men, did Lowell comply with an order from Van Dorn to advance. Even then, rather than assault Corinth, he only brought his division up to contact Moore’s right flank. Near sunset, Lovell halted a half-mile short of the Union fortifications around Corinth.

Both sides lay on their arms during the night; the temperatures quickly dropped from the daytime highs. The skirmishers from both sides kept the night lively with the sound of musketry. When the moon rose, it astonished the men with its brilliance, “The brightest moon I ever saw,” remembered Samuel Byers of the 5th Iowa.

Rosecrans, sure the Confederates greatly outnumbered him, felt he must secure Corinth’s inner fortifications. These fortifications consisted of five artillery redans forming an arc northwest of Corinth. He posted McKean’s Division on the left, on College Hill. Brig. Gen. David Sloane Stanley’s Division supported Battery Robinett. “Davies was to extend from Stanley’s right northeasterly across the flat to the Purdy road.” Brig. Gen. Charles Smith Hamilton’s Division formed on Davies’ right with one brigade, the rest of the division in reserve. Col. John Mizner’s cavalry “was to watch and guard our flanks and rear from the enemy.”

The Rebels under Van Dorn reorganized during the night and maintained the positions held at the close of the struggle. Lovell held the right, Maury the center and Brig. Gen. Louis Hébert the left. Van Dorn thought the Yankees might be evacuating Corinth but Green disagreed, “What made me doubt they were evacuating was the chopping of timber,” this would mean adding to the abatis. Rosecrans had reinforcements coming; Brig. Gen. James McPherson had orders from Grant to march four regiments from Bethel “with all speed.” but they would not arrive in time.

Van Dorn determined to attack at dawn, with an artillery barrage at 4 a.m. Hébert would begin the attack from the left, with Maury to charge Corinth as soon as he “should observe the fire of the Missourians, who were on my left, change from picket firing to rolling fire of musketry.” Van Dorn commanded Lovell to form his division with two brigades in front and one in reserve. He should then wait until Hébert engaged, when he would “move rapidly to the assault and force his right toward the low ground southwest of town.”

The temperatures on October 3 had been unseasonably hot and though the following morning saw frost, the heat would return with the sun. At 4 a.m., the night exploded with cannon fire. “What a magnificent display! Nothing we had ever seen looked like the flashes of those guns. No rockets ever scattered fire like the bursting of those shells!’ related Col. John Fuller. He commanded a brigade in Stanley’s Division.

The Rebel artillery got no response from the Federals for over an hour; the Federal artillery waiting for dawn to reveal the source of the barrage. The Union 30-pounder Parrotts in Batteries Robinett, Williams, and Phillips began to return fire at 5:15 a.m. It took less than 30 minutes to silence the Confederate guns and a calm fell. Van Dorn sent three staff officers to ascertain the cause of the delay, with none able to locate Hébert. At 7 a.m., Hébert reported at headquarters and asked to be excused from his command due to illness. Price put Brig. Gen. Martin Green in command of the left wing.

Hébert had not informed his brigade commanders of the plan of attack for October 4. When Price delivered word to Green, eating breakfast behind his brigade, that he commanded the division. “Green, upon whom the authority then fell, was hopelessly bewildered, as well as ignorant of what ought to be done,” said Lt. Col. Robert S. Bevier. Green put Col. William H. Moore in charge of the brigade and began to inspect his division’s lines. About 10 a.m., “somebody concluded we had better charge, and the order was given,” stated Bevier.

“With a wild shout, our whole brigade jumped swiftly across the railroad and charged toward the enemy’s line,” recalled Major Finley L. Hubbell of the 3rd Missouri, Col. Elijah Gates’ Brigade. They charged with their left in the air, Col. Robert McLain and Col. W. Bruce Colbert lagged. In addition, they had no reserve; without informing Green, Maury ordered Brig. Gen. William Cabell to fill a gap on Brig. Gen. Charles W. Phifer’s left.

“Stopping but a moment in the edge of the woods, to reform our companies, slightly discouraged by the fallen timber, our brave brigades pushed right ahead,” said Bevier. “The shot and shell from more than half a hundred guns crashed and whistled around us incessantly.”

“The very earth shook; the plain was swept with every conceivable projectile—round-shot ploughed up the ground, raising volumes of dust; shells went shrieking above and around, exploding and filling the air with their deadly contents,” Ephraim McD. Anderson of the Missouri Brigade recalled. “A perfect tornado of grape and canister came whizzing and pouring upon us, and, as we neared the works in the face of this storm, the rattle of musketry and the hissing of minie balls were added.”

Half a mile of open ground separated the Confederates from Battery Powell, with clouds of Yankee skirmishers standing in the way. The Union artillery fire butchered many men of Gates’ and Moore’s Brigades before they could close. The carnage would have been worse, but the blue-clad skirmishers masked much of the fire from the artillery around Battery Powell.

Moore and Gates paused to reorganize their ranks, 200 yards short of their objective. Then they let loose a volley and charged on at a double quick. This broke the will of the Union defenders and entire regiments collapsed. The Iowa “Union Brigade” dissolved first, followed by the 7th Illinois on their left. Rosecrans rode into the fleeing men, trying unsuccessfully to rally them. Col. Thomas W. Sweeney’s Brigade stood after the artillery batteries on either side broke and “galloped off in wild confusion.” The artillery limbers and caissons ran through Sweeney’s reserves, crushing some of the men, and routing the rest. The Union ammunition wagons behind the line stampeded “and they too started on the run to the rear,” reported Davies. He started after the men, trying to rally them. When an officer refused to return to the front, Davies drew his revolver and killed him, then galloped on.

Battery Powell had five guns, with their crews and horses, crammed inside the redan. Many of the artillerymen ran away when they saw the cannoneers and infantry on each side streaming away. Lt. John Brunner, commander of Battery I, 1st Missouri Light Artillery, released their horses and ordered his remaining men to retreat, leaving the guns behind. The remaining artillerists in the battery followed suit.

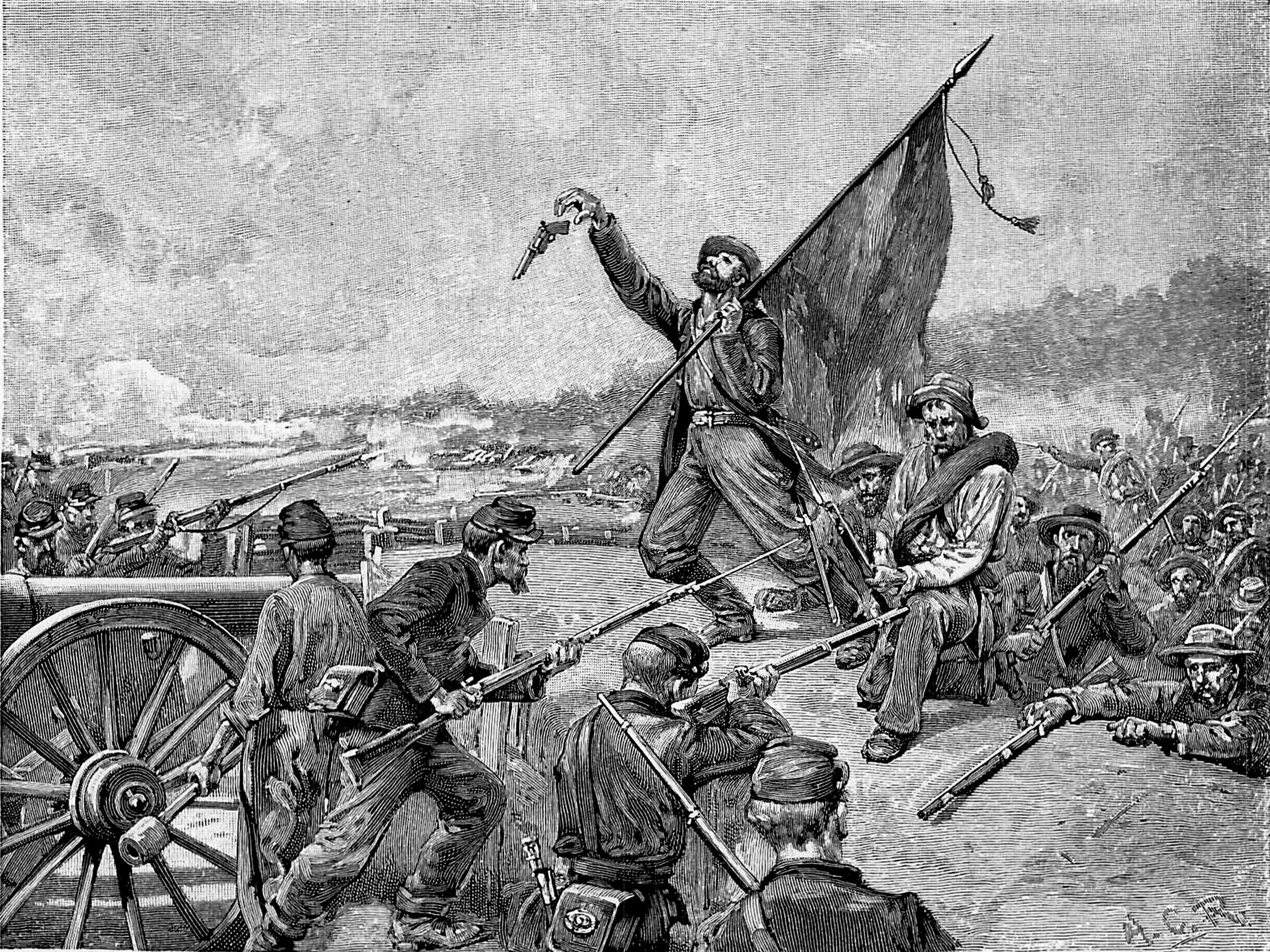

Gates’ Missouri and Arkansas Brigade smashed into Battery Powell. “One of the bloodiest places I ever saw,” said William Boyle, one of the Missourians. They streamed over the breastworks and fired a volley into the 52nd Illinois, breaking them. Only one Union battery remained on the field and Col. Francis Cockrell, commanding the 2nd Missouri, yelled “Forward, my boys, we must capture that battery.” The Federal cannoneers stayed with the cannon until the Missourians overran it, but finally had to retreat. They saved their limbers and caissons but lost all six cannon.

At 10:45 a.m., Colonel August Mersy’s 9th Illinois faced the Confederate Missourians alone. Mersy got his men into line, and they held on long enough for the Yankee fugitives to safely escape. Gates’ gray and butternut clad soldiers punched a hole in the Union line, but they had exhausted themselves in doing so. Almost as disorganized as the Federals; they needed aid, but none came. McLain and Colbert had not penetrated the Union line and Maury had not even begun his attack. The men of Gates’ Brigade held the captured breastworks but did not move forward.

The 12th Wisconsin Artillery Battery, flanked by the 56th Illinois Infantry on its left and the 10th Missouri on the right, had not been engaged and stood ready to assist. As soon as the Union fugitives cleared their front, the infantry opened fire on Gates’ men. The artillery joined in, firing double-shotted canister. The Confederates “fled, leaving their dead and wounded behind. When they started on the retreat they ran like frightened sheep,” said a Wisconsin cannoneer. The 56th Illinois and 10th Missouri charged down the hill after them. “On we went, yelling at the top of our voices,” remembered a 10th Missouri Yank.

At Battery Powell, Bevier saw the oncoming Federals, “While looking at them in dismay … my horse was shot through, and the ball flattened against my ankle … on arising, found it all safe and sound, though somewhat bruised … when the order came to fall back—and it was time.” They did not withdraw in an orderly fashion though; “A panic seemed to seize all the men,” said Hubbell. The Rebels retreated through the same fire they had charged through as the Yankees rushed forward to man the artillery once again. At 11:30 a.m., Gates’s men returned to the safety of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad embankment.

During the hour Gates’ men held the Union breastworks, McLain and Colbert fought a stand-up fight with Brig. Gen. Napoleon B. Buford’s Brigade in the timber 400 yards east of Battery Powell. The Union artillery tore swaths in their ranks and, when the Confederates reached a range of 75 yards, Buford’s infantry fired a volley. “I was in the rear rank. I raised my musket and blazed away at nobody in particular. A comrade in front of me afterward said ‘I nearly shot his ear off,’” said Private Samuel H. M. Byers of the 5th Iowa.

The fire from the Union line brought the Confederates to an abrupt halt. They endured the carnage for 45 minutes. McLain fell, his leg taken off by a solid shot. This took the fight out of his brigade; they fled, with Colbert’s Brigade following. In the words of Willie Tunnard, 3rd Louisiana, Colbert’s Brigade, “By this time so many had fallen, that no further progress could be made against the overwhelming forces of the enemy. It would have been madness to have made the attempt, and the brigade was compelled to retreat.”

Colonel W. H. Moore, on Gates’ right, still advanced after Gates withdrew. The Federals in his front had no reserves and he chased them into the streets of Corinth. But it was only a momentary Rebel victory, for a door-to-door conflict ensued and they were driven out.

Maury’s Division moved against Battery Robinett, southeast of Battery Powell, along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad line. His boys had been under fire from the Union artillery of Batteries Williams and Robinett since dawn. Instead of moving out right after Gates, Maury did not begin his attack until 11 a.m. Capt. Oscar Jackson of the 63rd Ohio, to the right of Robinett, awestruck as he viewed Dabney Maury’s advance, recorded, “As soon as they were ready, they started at us with a firm, slow, steady, step… Not a sound was heard but they looked as if they intended to walk over us.”

The first Union shell from Battery Williams detonated in the middle of the 42nd Alabama, killing or wounding 40 men. “You could see the poor fellows throw up their arms and leap into the air, and fall down. Still they pressed on,” said a soldier in the 39th Ohio. The Confederate advance slowed when they came to the abatis, but still they moved on, “clambering over logs & creeping under brush—firing & loading as fast as possible but still moving on,” remembered Texan James C. Bates.

After they cleared the abatis, they reorganized and charged Battery Robinett from 50 yards away. They “were met by a perfect storm of grape, canister, cannon balls, and minie balls. Oh God! I have never seen the like! The men fell like grass. I saw men, running at full speed, stop suddenly and fall upon their faces, with their brains scattered all around; others, with legs and arms cut off, shrieking with agony,” recalled Lt. Charles Labruzan of the 42nd Alabama. Five Rebel regiments faced Fuller’s Brigade and the Battery Robinett artillery.

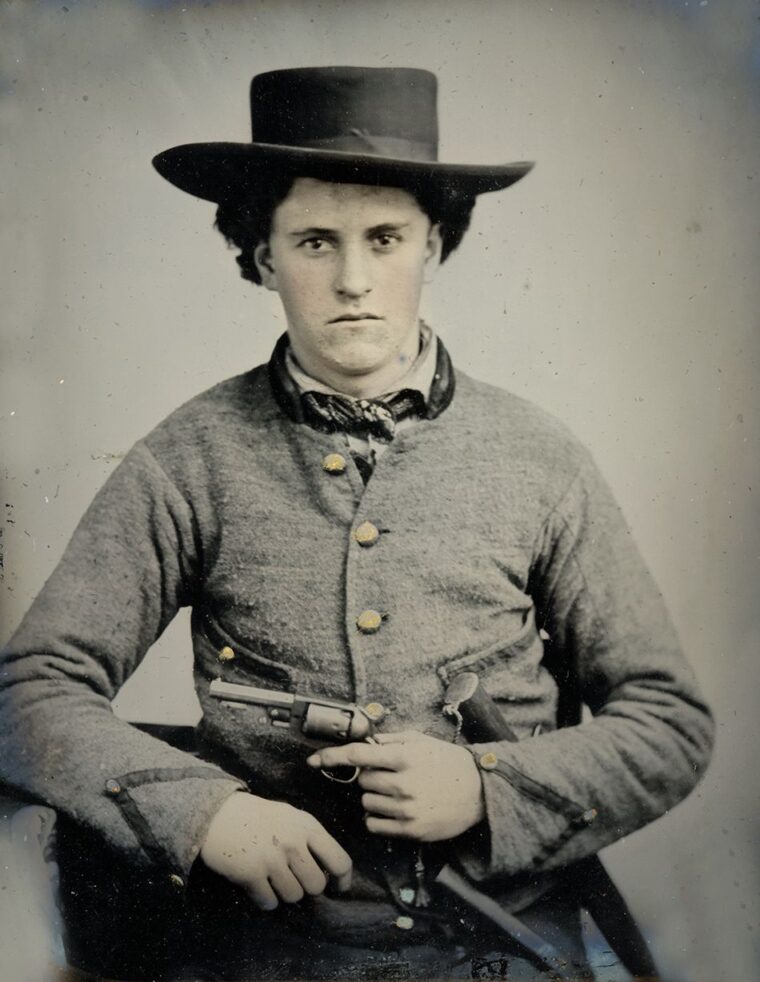

Colonel William P. Rogers led the 2nd Texas Infantry directly against Battery Robinett. The first and second assaults failed, and the Rebs reformed for their third try. Col. Rogers rode among all the regiments of Moore’s Brigade, goading them to greater exertions on their next attack. Unsheathing his sword, he cried, “Forward, Texans.” The Rebel infantry charged at a dead run. “One ball went through my pants, and they cut twigs right by me. It seemed by holding out my hand I could have caught a dozen,” declared Lieutenant Labruzan.

With Battery Robinett just 40 yards away, the butternuts went to ground, lying flat and grasping the dirt. The Yankees started throwing grenades over the wall. A Rebel officer screamed, “Over the walls, and drive them out.” Men from the 2nd Texas, 35th Mississippi, and 42nd Alabama charged at Battery Robinett. Col. Rogers, mounted on his black mare, halted his horse near the ditch, firing his pistol into the embrasure. The men with him fired a volley into the left flank of the 63rd Ohio.

Rogers led his men in an attack on the battery. “The next instant the Texans began yelling like savages and rushed at us without firing,” Oscar Jackson said. “Don’t load boys, they are too close on you, let them have the bayonet.” In a fierce hand-to-hand struggle, the Ohioans pushed the Confederates out of the redan. One of the Rebels turned to fire a last shot. “I saw the fire was aimed at me and tried to avoid it, but fate willed otherwise and I fell right backwards. I was struck in the face,” recalled Jackson.

The Yankee 11th Missouri, and a few men from the 63rd Ohio, attacked the Southerners in front of Battery Robinett. Surrender being the only option, Rogers grabbed a ramrod from Private T. B. Arnold of the 35th Mississippi and tied his handkerchief to it. The Union soldiers did not see it and fired a volley into the little Confederate group in front of the redan. Rogers and his mare fell beside a large stump in front of Battery Robinett. He wore body armor, but it proved to be of no use; at least seven balls hit him at close range. The Confederates had no choice but to retreat, under heavy fire from the Yankees in and around Battery Robinett.

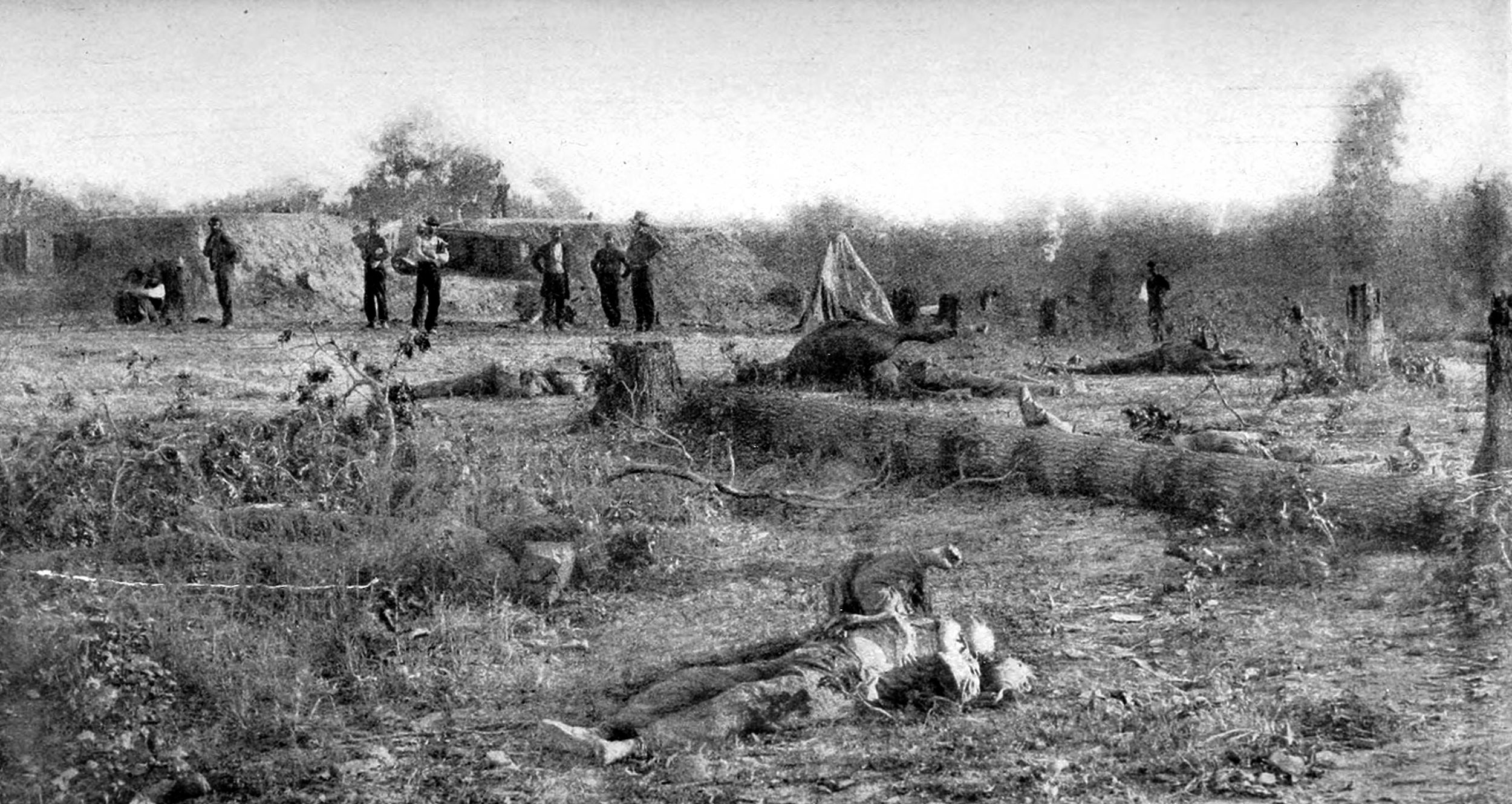

Lowell never came into action and many Confederate officers and soldiers felt the battle would have been successful if he had. The Rebels retreated to the positions from which they had started their attack in the morning. Rosecrans did not push them, and they spent the night there before beginning their retreat. When they reached the bridge over the Hatchie, they found a Union division from Bolivar, under Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut disputing the crossing. They had to march downriver, to a mill dam, where Price built a bridge for the escape of Van Dorn’s army. Justifiably, the Federals claimed victory over the Confederates to end the Battle of Corinth.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments