By Wil Deac

The morning sun caressed the hills of the Czech capital of Prague, coaxing a slight haze from the ancient city. On the banks of the winding Vltava River that bisects the capital, the chestnut trees were thick with flowers. On the surface, if one could overlook the German-occupation troops, May 27, 1942, was the stereotype of the perfect spring day, serene and mellow.

“I Shall Succeed the Fuhrer”

In the northern suburb of Holesovice, where a street named Rudé Armády VII swung into a hairpin curve as it descended from the pastoral highlands to the heart of the city, two men walked up to trolley stop No. 14. Each wore a comfortable suit and cap; each carried a briefcase. In appearance, they were businessmen en route to work. In fact, they had parachuted in five months earlier from a British plane. In his briefcase, Jan Kubis had a grenade. His companion, Josef Gabcik, had a submachine gun in his. Several hundred feet up the hill, Josef Valcik, also a parachutist, stood nonchalantly next to a telephone pole. In his pocket was an innocuous item, a small mirror. They were waiting to kill a man.

Their target was Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich, one of the most powerful and feared Nazis in Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. He was the man who had on one occasion boldly said, “I shall succeed the Führer.” And few had reason to doubt his word.

Nothing a Little Teutonic Efficiency Won’t Cure

The day after the Germans marched into Prague on March 15, 1939, Hitler sliced Czechoslovakia into two weak satellites, the protectorates of Bohemia-Moravia and Slovakia. Under the ineffectual hand of aging Baron Konstantin von Neurath, Bohemia-Moravia was anything but a valuable asset to Germany. The people were sullen and hostile, production was down, and there were acts of sabotage. Hitler decided to introduce Teutonic efficiency into the protectorate. For the job he selected Obergruppenführer (SS General) Reinhard Heydrich.

Tall and radiating an aura of authority, Heydrich was widely considered a prime example of the mythical Nazi master race. His slender physique was marred only by incongruously wide hips. The general’s lightly complected face topped by closely combed blond hair was narrow, the nose beak-like. His eyes, almost Asian in shape, were a hard, staring blue. Highly intelligent and quick-thinking, he was an accomplished pilot, fencer, and violinist; his father was a music teacher. Heydrich was raised a Catholic, but was wrongly rumored to have Jewish blood.

Promising Naval Career Derailed By Arrogant Womanizing

Heydrich initially set out to be an officer in the pre-Hitler German Navy, but was derailed by his arrogant womanizing. Already engaged to the woman he subsequently married, he involved himself with another. The latter’s father was an influential friend of the naval chief, and Heydrich found himself on the street during the 1930’s depression. It was a short step to Nazism. From a modest start as a Nazi street fighter, he rose to become a power behind the throne. He was the will and the brain behind Heinrich Himmler, head of the all-powerful Schutzstaffeln (SS Protection Squads of the Nazi Party). His craftiness not only asserted itself in playing one top Nazi against another, but also enabled him to compile compromising files on almost all of them. In the words of Walter Schellenberg, the party’s foreign intelligence chief, Heydrich “was the hidden pivot around which the Nazi regime pivoted. The development of a whole nation was guided indirectly by his forceful character.”

Heydrich’s hand was heavy in most of the history-making events of the 1930s in Germany: the infamous Night of the Long Knives, the 1934 blood purge of the party; the sex scandal frame-ups that rocked the German Army General Staff in 1938 and put the generals firmly under the Führer’s thumb; the Salon Kitty, the spy-ridden brothel that catered to foreign diplomats and businessmen; and the forgery of documents incriminating the Soviet general staff, which ended in the Moscow Trials of 1937-1938. He helped engineer the takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia. He set up the incident that sparked World War II, when a fake attack on the Gleiwits radio station gave Hitler an excuse to invade Poland in 1939.

Evil Mastermind Behind the Final Solution

It was Heydrich who stood over Adolf Eichmann and the Final Solutions, the liquidation of Jews. And it was Heydrich who outlined Plan Ost, the schedule for the extermination of Slavs. He truly earned his various nicknames—Heydrich the Hanger … the Man with the Iron Heart … Puppet Master of the Third Reich … Butcher of Prague.

Reinhard Heydrich arrived in Prague on September 27, 1941, to take up his post as acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia-Moravia. At the age of 37, he would be wearing two very important hats—the new one as ruler of the Czech people and the old one as head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, Reich Security Main Office). The latter, under the SS, comprised all of Germany’s security formations, including the Gestapo (short for state secret police). Shortly after Heydrich established himself in historic Hradcany Castle, situated atop a hill overlooking Prague, things began to change. In a high-pitched, stammering voice that belied his character, he declared a state of emergency.

Heydrich Gets To Work Quickly In Prague

The puppet Czech government was dismissed, its officials, including the prime minister, arrested. A month-long wave of terror swept Bohemia-Moravia. Lists of subversives, real or potential, were prepared. Men and women disappeared. Executions followed. Heydrich’s purpose was to eliminate the Czech leadership. Once the intelligentsia—the political leaders, teachers, doctors, scientists, engineers, lawyers, and others—were removed, the people could be more easily controlled. The bribery of higher wages and incentive prizes balanced by the threat of the firing squad would make the masses powerless, but productive. It was the old story of the carrot and the stick. Nor did Heydrich ignore the “racial issue.” He had 94,000 Jews deported to newly conquered Russian territory to make way for German settlers.

To the dismay of the Allies, Heydrich’s cynical policy appeared to be working. So well, in fact, that, with Berlin’s blessing, he planned to export his methods to other parts of occupied Europe. Hard pressed on every battle front during the dark days of 1941, and trying to encourage underground movements on the Continent, the Allies found the idea of a Czechoslovakia allied to Germany unthinkable. Eduard Benes, head of the government-in-exile formed by the Czechs who had fled to Great Britain, thought he had the answer to the problem—assassinate a top Nazi. It would prove the viability of the small Czech Underground, gain prestige for his government-in-exile, and rejuvenate the resistance to “provide a spark activating the mass of the people.”

Operation Anthropoid Hatched

Benes consulted his intelligence chief, Lt. Col. Frantisek Moravec. The result was Operation Anthropoid, the elimination of the Butcher of Prague.

Secrecy was paramount to make the assassination appear to be “a spontaneous act of national desperation.” Only a very few would be told of the operation. Even the British, who would have to provide the training, weapons, and transportation, would not be told. The Anthropoid team would work alone, avoiding contact with the mainstream of the Czech Resistance. Finally, since parachutists occasionally were dropped to strengthen and reorganize the underground, the insertion of the assassins would not be noticed. Such was the thinking.

Two noncommissioned officers already in parachute training were ultimately selected—Kubis, the son of Moravian peasants, and Gabcik, a former locksmith from Slovakia. Both were bachelors, since their chances for escape were considered minimal, which was possibly why so little thought was given to a postassassination escape plan. Kubis replaced another parachutist who had been injured in a training accident. When the 20-year-old Czechoslovak Republic was sacrificed by the appeasement of Britain and France in 1939, the country’s 16,000-man army was demobilized and sent home. Sergeants Kubis and Gabcik were two of these men. Leaving their homeland, they fought the Germans in France after the outbreak of the war. Following the French defeat, they joined the Allied evacuees in Great Britain, subsequently becoming part of a Czech brigade.

Vastly Different Conspirators United In a Common Cause

Czechoslovakia has been likened to an eastward-pointing shoe about the size of North Carolina. Its heel consisted of the province of Bohemia and included Prague. Moravia made up its narrow instep, while the long toe was Slovakia. The inhabitants of Bohemia and Moravia, said to be sober-minded and mechanically inclined, were known as the “Yankees of Europe.” The Slovaks, on the other hand, tended to be carefree and close to the soil. Dark-eyed Kubis, 28 years old in 1941, tall and slender, introverted and soft-spoken, was of a minority, a farmer in industrialized Moravia. Gabcik, 29, shorter and blue-eyed, temperamental but quick to smile, was also from an occupational minority, coming from an area where woodsmen, farmers, and herdsmen prevailed. The two were like the New Englander and the Southerner ribbing and jouncing each other, but presenting a solid front to outsiders.

In special training camps in the British Isles, the two sergeants learned how to be assassins. They did this under the watchful eyes of Staff Captain J. Jaroslav Sustr, a veteran of the Czech Underground who had escaped captivity to fight in Yugoslavia before becoming the executive officer in charge of training parachutists for missions behind the German lines. Chief of the Czech military mission in Berlin after the war, he defected to the United States after the Communist takeover of his country, Anglicized his name to Sustar, and pursued a number of activities. Sustr served with the FBI in Washington, DC, as an intelligence research specialist for 10 years before retiring in July 1988. He died less than four months later.

Returning To Their Homeland Under Cover Of Night

A four-engined British Handley-Page Halifax lifted from Tangmere airfield three days after Christmas 1941, crossed the English Channel, and overflew occupied France and Belgium. Inside the bomber’s fuselage were eight Czechs about to be parachuted back into their homeland. Besides Kubis and Gabcik there were a pair of three-man radio teams that were tasked with setting up intelligence networks, organizing supply drops for the resistance, and reestablishing radio contact, which Heydrich’s harsh measures had severed, between the underground and London.

The government-in-exile seemed to ignore the probability that Operation Anthropoid might trigger enemy reprisals that could nullify the radio teams’ efforts. Droning over Darmstadt, Germany, the Halifax was detected by two German night fighters. The latter lost their prey 20 minutes later. Luck deserted the bomber farther east as it descended through the overcast over Bohemia. Sustr, aboard because he knew the countryside, was unable to locate the drop zones due to the heavy snow blanketing all the landmarks. The decision was made to risk an imprecise drop rather than return to England with the parachutists.

Troubles Beset Team From Outset

Minutes before 2:30 am on December 29, Kubis and Gabcik dropped at a 500-foot altitude through the bomber’s floor hatch. Before he left, Gabcik shook Sustr’s hand with the words, “Remember, you will be hearing from us. We will do everything possible.” The radio teams, one of which included Josef Valcik, were dropped farther on. One would disband after finding its radio broken and the contact addresses it had been given useless. The second team, overcoming numerous difficulties, proceeded with its mission and contacted London.

When Kubis crunched across the crusted snow covering an open field and joined Gabcik, he learned the first of two discouraging facts that would delay the accomplishment of their mission. Gabcik, on landing, had badly injured his left foot. The second disappointment was the absence of the forested hills he expected. Instead of landing about 50 miles west-southwest of Prague near the city of Pilsen, the two had come down near a village some 20 miles from the capital. Their chutes buried beneath the snow, the men, Gabcik leaning heavily on his friend’s shoulder, took shelter in a nearby abandoned shed. There they cached their equipment and ate a quick cold meal. They then set out to find a better hiding place, which turned out to be a stone quarry.

A Confused Whirlwind Of Movement and Planning

Their discovery came quickly, fortunately by friendly Czechs roused by the low-flying Halifax. The Germans failed to connect the aircraft with the parachute drops. Kubis and Gabcik were put in touch with the underground by the Czechs who found them. Although the parachutists had been instructed to avoid the resistance, they had no other choice since they were in no position to seek out the contact addresses in Pilsen they had been given. The weeks that followed were a confused whirlwind of movement and planning. Kubis and Gabcik were hustled from one hiding place to another. They received new documents to replace the faulty ones issued in Britain. Gabcik’s foot was given time to heal.

London, in the meantime, was growing desperate to hear from the Anthropoid team. If it had been neutralized, a new assassination squad would have to be chosen, trained, and flown out. The government-in-exile’s intelligence chief, Moravec, initiated another deviation from the original scenario, which called for Kubis and Gabcik to operate independently without unplanned contacts. He ordered the successful radio team that had parachuted at the same time as the Anthropoid duo to find out what happened to Kubis and Gabcik.

Still Time For Romance In The Midst Of Drama

Ironically, it was Valcik who, almost by accident, located the two. Hotly pursued by the Gestapo in his designated area of operation, Valcik found refuge in Prague with the same group that was hiding Kubis and Gabcik. All this time, the pair kept the nature of their assassination mission to themselves. It was during this time, too, that they found romance. Kubis became deeply involved with a blue-eyed, dark-haired girl named Anna Malinova. Gabcik’s love interest, 19-year-old Libena Fafek, quickly became his fiancée.

As the days passed, the plot to kill Heydrich gradually took form. Using every source at their disposal—loyal contacts, personal observations, loose bits of information—Kubis and Gabcik began to stalk their quarry, often by bicycle. They learned details of the Reichsprotektor’s office in Hradcany Castle. But there, surrounded by SS guards, he was inaccessible. They scouted his home. The Butcher of Prague lived in a lavishly furnished white chateau, confiscated from a Jewish sugar magnate, with his blonde wife, Lina, and three children in Panenske Brezany, a small village about 12 miles northeast of Prague. The town had been cleared of Czechs and occupied by German troops. The chateau also was heavily guarded.

Key To The Plot: Heydrich’s Commuting Schedule

Heydrich’s commuting schedule was studied. When not traveling outside the capital, he drove between home and office at regular hours in a green Mercedes Benz convertible. His fairly regular trips to Berlin were made usually by train, sometimes by air. The only feasibly exploitable security gap appeared to be Heydrich’s drive to work, which was done without an escort. This fit in with their training in Britain, which had concentrated on attacking a car.

The Anthropoid team was still examining Heydrich’s lifestyle in March 1942 when London parachuted two new radio teams into Czechoslovakia. Both suffered a series of irreparable mishaps. Those who were not captured or killed made contact with the resistance and ended up in Prague, adding to those now connected with the Anthropoid team. One of the newcomers was Sergeant Karel Curda, who was to play a crucial role in future events. The fates of these and successive parachute teams indicated not only that the government-in-exile’s program was a failure, but also put the men already on the ground in peril.

Czech Government In Exile Confuses Matters

To further aggravate matters, Operation Anthropoid’s purpose gradually became apparent to others in the resistance. This, predictably, led to a split between those who justifiably feared that Nazi reprisals would compromise them all and those who were determined to go ahead. The government-in-exile, also divided about going ahead with Heydrich’s assassination, was of little help when the resistance asked for a decision.

Benes either confirmed the mission or ignored the underground’s request (accounts differ). In any case, despite the shaky security of the fragile underground, the Nazis did not learn of Anthropoid. They did, however, suspect something. One of the local Gestapo officers, citing the increased confiscation of terrorist and assassination devices parachuted in during the spring of 1942, was quoted as saying, “We suspected more and more the possibility of an assassination and stepped up our defenses accordingly.” Despite this, overconfident and arrogant, Heydrich persisted with his unconvoyed commute.

An Assassination Site Selected

After considering several alternatives, Kubis and Gabcik decided to climax their deadly game on the curving street in Holesovice. The black-topped highway from Panenske Brezany was transformed into a cobblestoned street with trolley tracks as it wound downhill through Holesovice. As it made its final descent toward a bridge spanning the Vltava, the mainly residential street branched off in a sharp, 120-degree turn to the right. At the “V” formed by the hairpin turn was a tree-covered knoll enclosed by a brick, post-supported, iron-rail fence. The trolley stop between it and the street would give Kubis and Gabcik an excuse for standing there without appearing too conspicuous. The assassins, working under pressure that included a rumor that Heydrich was about to leave Prague, decided to strike on May 27. Gabcik was to shoot the Butcher of Prague, while Kubis provided backup.

At about 9 am that fateful Wednesday in May, Oberscharführer (Technical Sergeant) Klein drove Heydrich’s open Mercedes up to the front door of the Panenske Brezany chateau. While his bodyguard-chauffeur waited, the Reichsprotektor delayed his departure to play with his two sons and daughter in the garden. He then kissed his pregnant wife good-bye. Later that day, he planned to fly to Berlin for a meeting with Hitler. It was nearly 10 o’clock when Heydrich seated himself in the right passenger seat of the car. Klein steered the powerful, two-door convertible down the driveway and out the gates past saluting guards.

Quarry Departs In Luxury Convertible, Hunters On Bicycles

Earlier that same morning, Kubis and Gabcik left their in-town hideout and boarded a trolley to the eastern suburb of Zizkov. They left there on borrowed bicycles, briefcases secured to the handlebars. They were leaning the bikes against lampposts in Holesovice at about 9 in the morning. Valcik was already there waiting. After a brief exchange of words, Valcik walked up the hill to take up his observation position, Kubis got behind a lamppost beneath some trees near the hairpin turn. In his briefcase were two canister grenades provided by the British.

The grenades basically were customized smaller versions of explosive devices used against tanks in North Africa. Kubis had earlier unscrewed the caps and set the short-timed fuses. A British bacteriologist subsequently said the grenades contained botulinal toxins to ensure that even if Heydrich were only slightly wounded he would be infected with the poison. This has never been confirmed. Gabcik opened his briefcase and deftly assembled the three components of his Sten submachine gun, also British-supplied.

Sten “Woolworth Gun” Weapon Of Choice

The roughly seven-pound Sten, known as the “Woolworth gun” because it was easily and cheaply made, was an effective short-range weapon. It could spit out the 32 rounds in its left side-fitted magazine in less than four seconds. Gabcik, light all-weather coat slung over his arm as a weapon-concealment device, crossed to the west side of the street to stand in front of the knoll’s rail fence.

One can only imagine the buildup of tension as the Anthropoid team waited for a target they undoubtedly began to fear would not come. Heydrich had never been late before. Several trolleys, red coaches linked together, clanked to within feet of the curb near Gabcik to pick up and discharge passengers. Then, with a crackle of sparks from the overhead wires that powered them, they continued noisily on their way.

Foot and vehicular traffic lightened as the rush hour elapsed. Chances of detection increased exponentially. Where was Heydrich? Finally, at about 10:30, the Mercedes appeared around a curve up the road. Valcik flashed sunlight off his mirror and took off. Moments later, the car’s transmission noise changed to a loud whine as Klein downshifted the gears to negotiate the sharp curve. The green convertible was barely moving as it reached the assassins.

Sten Jams and Fateful Turn Of Events

Heydrich had to see his assailant as Gabcik, tossing aside his coat and briefcase, moved toward the street with his weapon. His first feeling must have been one of disbelief: Sten gun at his shoulder, Gabcik squeezed the trigger—but nothing happened. As the car moved around the hairpins, he followed it with the barrel of his submachine gun. Still, presumably jammed, the weapon refused to fire. Heydrich, making the worst arrogant decision of his life, rose from his seat, pulled a pistol from his holster, and shouted to Klein to stop.

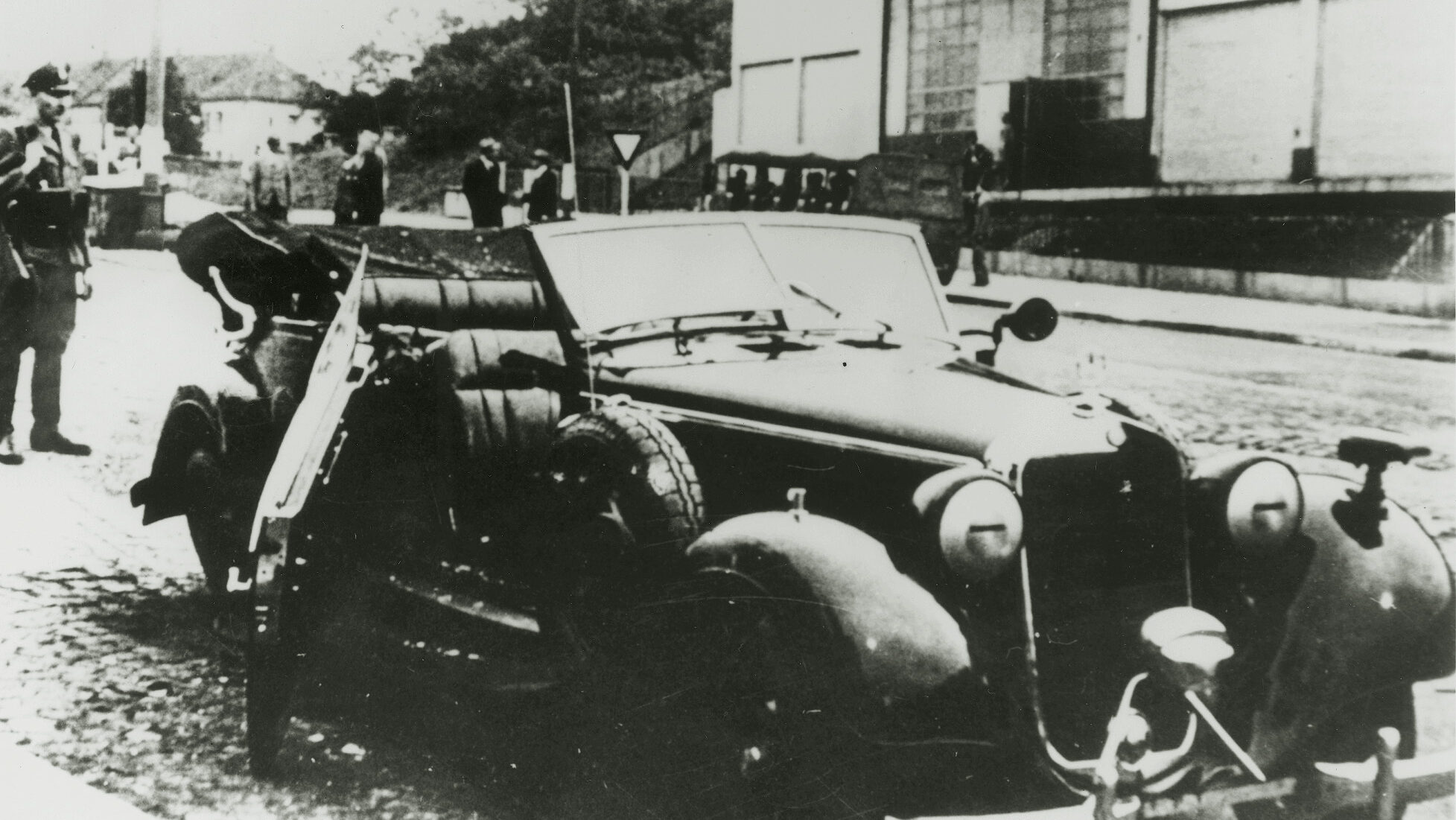

Their attention focused on Gabcik, the Nazis failed to see Kubis approaching. The Czech flipped a grenade. Badly tossed, it erupted in flame and smoke against the Mercedes’ right rear wheel. The back of the car briefly lifted into the air, and the two uniform jackets folded on the rear seat flew upward to hang temporarily on the overhead trolley wires.

The blast shattered windows on a trolley that had just reached the nearby stop. Cries of the injured filled the smoke-tainted air. Kubis, hat blown off and hit by shrapnel, was momentarily stunned. He quickly recovered and, bleeding from his wounds, ran for his bicycle. Pulling a Colt semiautomatic from his jacket, he fired a shot into the air to clear a way through the shaken and angry passengers piling out of the trolley cars. Gabcik flung aside his useless Sten and ran for his bike.

The Hunted Turn On Their Attackers

In the meantime, pistols drawn, Heydrich and Klein took off after their attackers. The Reichsprotektor pursued Gabcik, while his bodyguard concentrated on Kubis. Klein, having made his way past the tram passengers, took aim at the assailant beginning to pedal his way down the street. In his excitement, he accidentally pressed his pistol’s magazine-release button.

Undoubtedly embarrassed, the burly sergeant turned back to help his boss. The bleeding Kubis got away and shortly was back at the Zizkov house where he had earlier picked up his bicycle. By early afternoon, he was at a second safe site having his wounds tended by a doctor. To all appearances, he had failed in his mission. Heydrich, meanwhile, fired at the fleeing Gabcik. Several seconds behind his companion, the parachutist found himself cut off from his bike by the crowd. Instead of trying to break through, he drew a revolver and darted across the street in front of the trolley.

Gunfight Erupts On Streets Of Prague

He stopped behind the slim cover of a telephone pole to return the German’s fire. Heydrich pinned him down from behind the trolley. What was supposed to have been an efficient assassination had turned into a gunfight with all the melodrama of a Hollywood Western. Gabcik knew it was only a matter of minutes before a posse of policemen or Nazis would arrive to kill or capture him. Already, he could see Klein’s hulking figure pounding back up the street toward them.

Then, Heydrich suddenly bent over and staggered back to the sidewalk, reeling against the railing at the base of the knoll. Seeing that the German was obviously hurt, Gabcik began running up the hill. Klein reached his boss’s side. Whether the ashen-faced Reichsprotektor said “Go after him” or “Get the bastard” (accounts differ), his order was clear. Klein raced after Gabcik. The latter turned off the main street and sought refuge in a butcher shop. There was no back door; worse yet, the owner was a collaborator with the German occupiers. He ran outside and directed Klein to Gabcik’s hiding place.

Extent Of Heydrich’s Wounds Slowly Revealed

Unfortunately for the German, his pistol was jammed from his earlier gaffe. As Klein ran into the shop, his quarry dashed out. As the two collided, Gabcik shot his pursuer in the leg, sending Klein to the ground. For good measure, as he moved past the fallen man, Gabcik fired another shot. It hit the Nazi’s ankle. The parachutist sped to a safehouse. The fleeing assassins had no way of knowing that they had mortally wounded their prey.

Red stains spreading around several small tears in the back of his uniform, Heydrich moved stiffly back to the wrecked car. Kubis’s grenade had broken a rib and blasted tiny pieces of steel and upholstery from the car into the Nazi’s back. They had ruptured his diaphragm and dug deeply into his spleen and lumbar region. A woman in the hitherto unmoving crowd recognized the Reichsprotektor and called for a car to take the wounded German to the hospital. An open-backed truck was flagged down by one of the trolley passengers. The driver was averse to getting involved. A second truck was stopped.

It was shortly after 11 am when the Reichsprotektor of Bohemia-Moravia arrived at Bulkova Hospital lying in the dirty back of a truck beside containers of floor polish. Early that afternoon, after insisting on a German doctor, Heydrich was wheeled into the operating room.

Nazis Retaliate With Crackdown

Initial German confusion and fear that the assassination attempt was part of a more widespread conspiracy were quickly replaced by the type of repressive measures that were a trademark of the Third Reich. Martial law was proclaimed. A reward of 10 million Czech crowns (about $400,000) was offered for the capture of the perpetrators. It was announced that 10,000 Czechs would be arrested and that whoever “hides the criminals or gives them help … will be shot with his entire family.” Notices appeared on city walls proclaiming a 9 pm to 6 am curfew, enforced by the death sentence. Areas were cordoned off and systematically searched house by house. Steel-helmeted soldiers were everywhere. Public places were closed, and transportation halted until further notice.

Between May 31 and June 4, 157 Czechs were executed, mostly for minor offenses, to express German dissatisfaction. Concurrently, a more focused police investigation began with an examination of the crime scene and the questioning of witnesses. The SS investigators recovered the Sten gun, a grenade in one of the two briefcases, a man’s coat and hat, and a woman’s bicycle.

The bike, briefcases, and clothes were displayed in the window of the downtown Prague Bata shoe store along with bilingual signs announcing the reward and asking, “Who knows the objects exhibited here?”

Assassins On the Run Across Prague

Despite these measures, several Czech families helped the parachutists move from one hiding place to another. Finally, squeezed by the Nazi manhunt, the underground decided to hide all eight parachutists in Prague in one place—the catacombs of the over two-centuries old Orthodox Church of St. Cyril and St. Methodius in the center of the capital. All but one were living in the church by early June, hoping to escape when things cooled down.

The one exception was Sergeant Karel Curda, who was hiding on his mother’s farm in southern Bohemia.

In a heavily guarded, no-Czechs-allowed ward of Bulkova Hospital, Heydrich fought for his life despite an initially optimistic postoperative prognosis. Himmler called several times a day to check on his right-hand man’s condition, and even paid him a visit. Blood poisoning set in as the tiny particles of material in Heydrich’s back remained and festered.

Butcher Of Prague Succumbs To His Wounds

On the afternoon of June 4, just over a week after the attack, feverish and in pain, the Butcher of Prague was dead. As to allegations that the grenade was poisoned, one British historian stated, “There is no need to believe this. Prague’s wartime suburban gutters were not clean, and the grenade fragments carried filth enough to kill him.…”

Furthermore, the fact remains that Kubis was not infected by the fragments that hit him. Elaborate funeral ceremonies took place in Prague and in Berlin. Hitler and Himmler attended the Berlin ceremony to eulogize the once powerful and ambitious satrap. Behind their public façade, however, they considered Heydrich stupid for driving in public in an unescorted open car. In addition, Himmler was rid of a man who threatened to overshadow him. The late Reichsprotektor was finally laid to rest in the Invaliden Cemetery in eastern Berlin on June 8.

The Czech government-in-exile in London was pleased to learn of Heydrich’s death, touting it as vindication of their country’s effective resistance to the German occupation. So were the Czech Communist leaders in Moscow. But both apparently underestimated the reprisals that would befall the people under Nazi domination.

Jews First To Suffer Reprisals

Not surprisingly, the first to suffer were Jews. An initial trainload of 19,000 left Bohemia-Moravia to be exterminated. In neighboring Poland, the mass murder of Jews was named Aktion Reinhard (Operation Reinhard) in honor of the dead Nazi. In their desperation to find the assassins and to punish the country, the Germans seized on flimsy evidence to single out the mining and farming hamlet of Lidice as having harbored parachutists.

Hitler telephoned Prague and ordered Karl Hermann Frank, the German state secretary under the Reichsprotektor, to destroy Lidice. All males over 15 were to be killed and women sent to a concentration camp. Children with Aryan characteristics were to be given to SS families. The SS surrounded Lidice, located about l0 miles northwest of Prague, on the late evening of June 9. After the 195 women and 95 or 98 children (sources differ) were removed and the 198 or 199 men (again sources differ) shot, the villagers’ 95 houses were burned down and the ruins bulldozed. After the war, a memorial was erected on the site, and a town called New Lidice arose nearby.

Kubis and Gabcik Betrayed

Kubis and Gabcik Betrayed

On June 13, while continuing to press their search and promising new reprisals, the Nazis tried a new tack. Frank announced that anyone who helped catch the assassins by June 18 would receive amnesty. This provided the break they needed. The parachutist Curda, no longer able to withstand the tension of hiding out, took a train to Prague and walked into Gestapo headquarters.

He gave the Germans the real names and aliases of Kubis and Gabcik, although he did not know their whereabouts. It soon became apparent to his interrogators that Curda was one of the parachutists, which gave them leverage in questioning him. One bit of information led to another until the Gestapo knew enough to raid several houses and arrest key members of the underground. One of them, under torture, provided the name of the parachutists’ hiding place.

Dawn was beginning to dilute the warm darkness on Thursday, June 18, when the rumble of numerous trucks broke the silence of Resslova Street in the old section of Prague. Hundreds of Waffen SS (Armed SS) troops disembarked to form a double cordon around the church named in honor of Saints Cyril and Methodius. A detail, led by Heinz Pannwitz, the Gestapo head of the assassination investigation, rang the bell by the church door. A janitor appeared, let them in, and turned on the lights.

Germans Surprised With Gunfire At Church

Boots clacking against the stone floor, the Germans searched the nave without turning up anything. The situation suddenly changed when they tried to gain entry to the choir loft. They were met by a grenade and gunfire. Apparently Kubis and two of his companions either had been on guard duty or, finding the crypt too confining, had been sleeping there. Troops posted on neighboring rooftops reacted to the outburst by wildly opening fire on the church. Tall windows disintegrated, masonry chipped, and slugs caromed around the high-vaulted interior.

The Germans in the church retreated to avoid the friendly fire. Once the Waffen SS commander restored discipline among the snipers, an assault on the choir loft was ordered. It took a couple of hours for the attackers, using grenades, to make their way up the narrow circular stairway into the battered loft. Two of the parachutists were dead, having swallowed poison capsules rather than be captured. The third, identified as Kubis, was mortally wounded.

It did not take the Germans long to learn, after questioning the chaplain who had given the parachutists asylum, that four other men were in the crypt. It had only one usable entrance, beneath a flagstone on the floor. Air circulated through the catacombs through a grill-covered vent high in the outer wall of the church. Hoping to take at least one of the parachutists alive for questioning, Pannwitz tried a psychological approach to induce them to surrender. This attempt, using a loudspeaker and the chaplain, failed. A captured member of the resistance and the betrayer Curda were then brought in to talk to the parachutists through the ventilation slot. The first refused to cooperate. When Curda pleaded, “Surrender, boys. It’ll be all right,” he was answered by a spray of bullets.

Germans Call In Fire Department For Assistance

Pannwitz, wishing to avoid a direct assault, turned to the fire department. A Czech fireman was soon climbing a ladder placed on the sidewalk beneath the vent. He pried off the iron grill. A hose was then snaked into the hole to pump 600 gallons of water a minute in a powerful stream into the crypt. This effort to flood out the Czechs had to be repeated more than once. Using their own ladder, the parachutists repeatedly pushed the hoses out or cut them, using the interval between to spit bullets and explosives at those outside. The Germans also threw tear gas cannisters down the hole; many came right back out to spew their contents on the sidewalk. In any case, the continual attempts at flooding were not working, possibly because much of the water was somehow escaping through the walls or floor. During this time, the four defiant parachutists also were trying in vain to dig a hole through one of the walls to escape.

State Secretary Frank, who had come to watch the action, began to show impatience as the siege dragged on. The Waffen SS commander took advantage of this. A direct military assault would quickly end what had become an embarrassing situation, he decided. The two approached Pannwitz, who insisted his way would save German lives and take the fugitives alive. Frank decided in favor of the SS.

SS Jumps Into The Fray

The stone covering the entrance to the crypt was lifted, and an SS detachment wearing gasmasks scurried down the ladder. As they waded through waist-deep water and tried to adjust their eyesight to the darkness, they came under fire. The parachutists were concealed in the rectangular seven-foot-deep recesses intended for the bones of deceased monks. The assault team, two of them wounded, pulled back.

The angry SS commander turned to a second possible way into the crypt. There had once been a doorway near the altar opening onto stone steps leading down to the catacombs. It had recently been sealed up. Blow it open, the officer commanded. Assault teams would attack simultaneously through both openings.

Siege Ended With Four Shots

Before the plan could be implemented, four shots echoed from below. The parachutists, all wounded, had killed themselves. Their bodies were carried outside to be lined up for identification by Curda. He immediately pointed out Gabcik as the second assassin. The Czechs had held out for more than six hours.

Still, the Nazis were not satisfied. Retaliation continued throughout the summer with new arrests and executions. They included 252 persons who were related to or aided the parachutists, as well as the former prime minister and church officials.

On June 24, another village near Prague, Lezaky, was visited by the Germans. There, all the adults and all but two children were slaughtered. In all, between May 28 and December 31, 1942, an estimated 1,940 persons were executed for the assassination of the Butcher of Prague. The Orthodox Church was dissolved, its property seized. Some 4,000 Czechs were interned in a camp as hostages. Curda, rewarded with five million crowns, adopted an alias and German citizenship. He became a Gestapo agent provocateur ferreting out resistance activities, real and potential. His luck ran out in 1946 when he was tried and hanged, a fate shared by Frank.

Czechs Pay High Price For Assassination

The Czech underground, never fully developed to begin with, was crippled, though not extinguished. British planes later conducted other parachute flights. These missions, however, were uniquely for intelligence work since active subversion had become virtually impossible.

At a time when they were on the defensive in most parts of the world, the Allies considered the assassination a major victory. Benes had shown, however debatably, that Czech resistance to the German occupation was alive and well. While Heydrich’s death was a serious blow to the Nazis, it also resulted in the smashing of what might have been a consequential underground movement. Instead, the Czechs were forced into a more passive form of resistance.

Shamefully, despite the benefits their action gave to the Czech government-in-exile, the parachutists were virtually disowned by Benes. Aside from the government’s reluctance to admit resorting to assassination, there was the political aspect of making the world believe the killing was strictly an internal matter. While neither the death of the Butcher of Prague nor the Nazi reprisals changed the outcome of World War II, they became key events in any history of that conflict.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments