By Peter Suciu

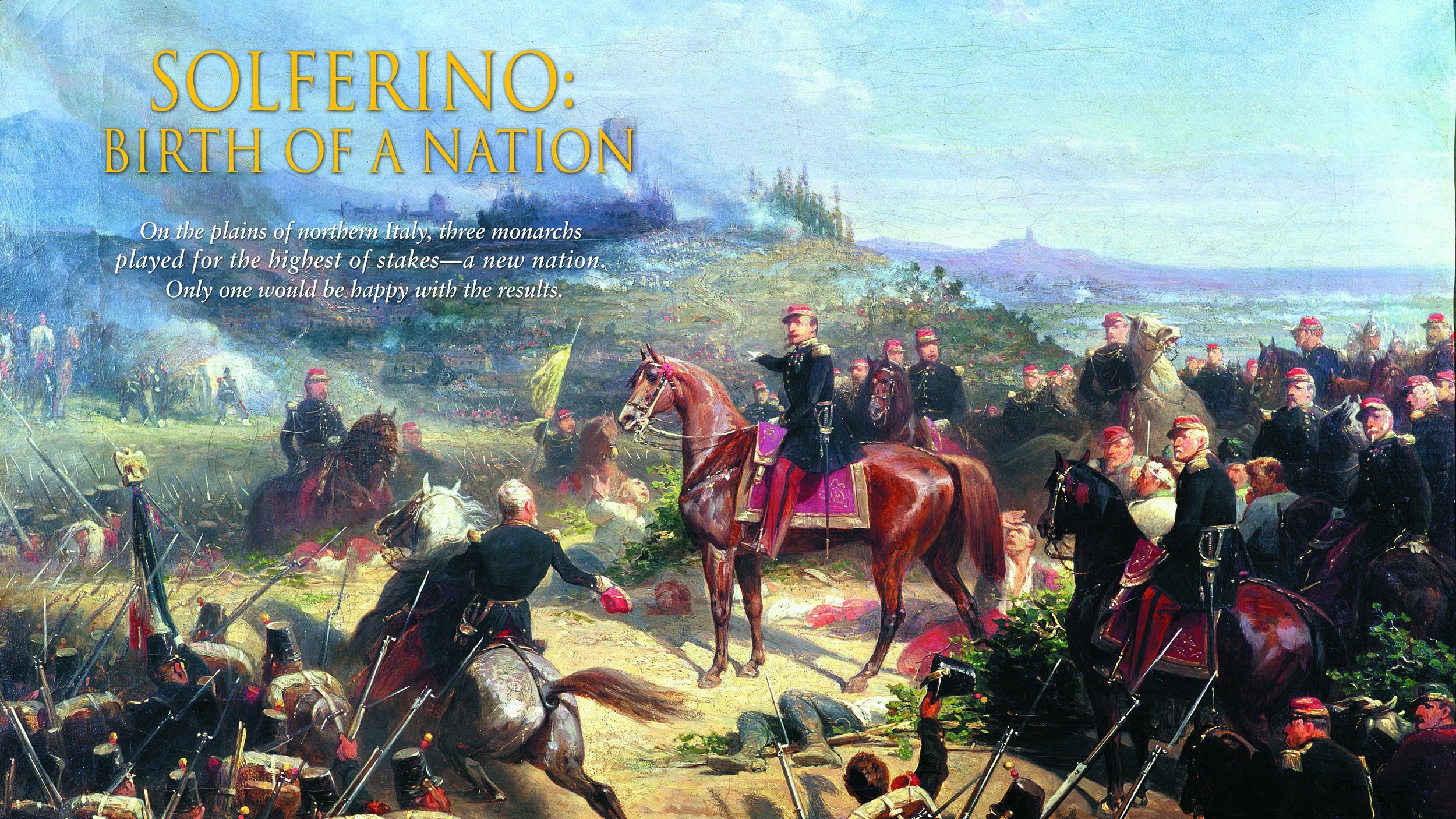

If a picture truly paints a thousand words, then Gerry Embleton has painted volumes in his career. As a freelance illustrator of military subjects, he specializes in highly detailed, accurate studies of historical costumes, including period uniforms. He has written and illustrated two photographic studies of medieval costumes and has created the artwork for more than 40 titles for the well-known military publisher Osprey.

Born in England, Embleton’s early life was much like that of the young boy in the film Hope and Glory, as he lived through the German blitz of London. After World War II, he studied part time at art schools in London and Brighton. After leaving school, Embleton became a freelance illustrator, working in comic strip publishing and advertising before finding his true passion illustrating historical subjects.

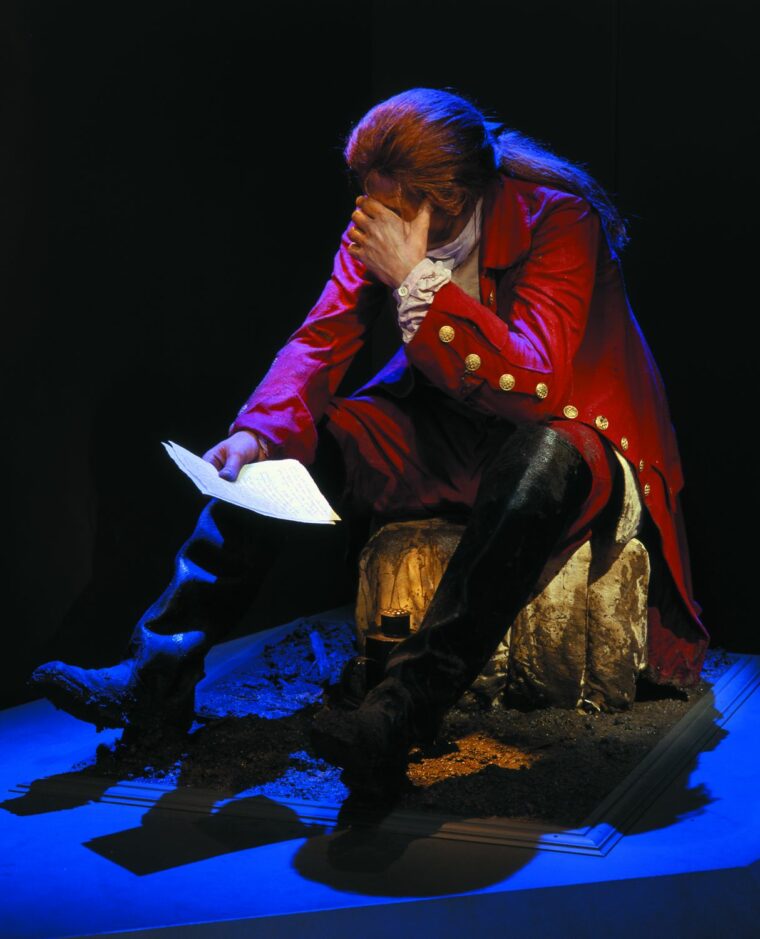

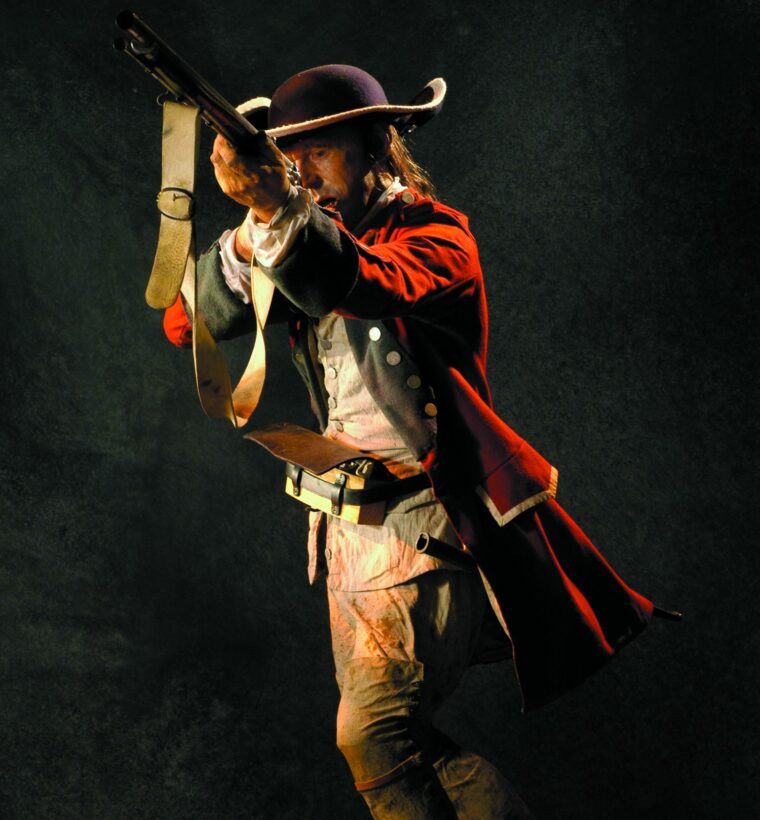

Embleton moved to Switzerland in 1983 to research 15th-century Swiss costumes, uniforms, arms, and armor and has lived in the mountainous country ever since. He was invited to work for the Swiss Institute of Arms and Armor at Grandson Castle and became its official artist and later head of the castle’s creative arts department. In 1988 he founded his own company, Time Machine AG, or TMAG, which produces life-size historical figures for exhibitions and museums. Much more than mere mannequins in uniforms, Embleton’s displays put costumes into a historical context. His first big assignment was the refurbishment of Lenzburg Castle, and the results were so well received that he won a European Prize. Since then, his company has completed more than 60 commissions in eight countries.

The past is very much alive in Embleton, who has had a lifelong passion for the medieval age. In 1986 he formed an international group to recreate the daily life of the late 15th century, and was invited to participate in Switzerland’s 700th anniversary. In 1991 he served as art director for the 600th anniversary celebration in the Swiss capital city of Bern.

Throughout his career, Embleton has always tried new things, and in his late sixties he took up landscape painting. He has exhibited his work in the United States, Switzerland, England, Scotland, and Canada. Today, Embleton divides his time between illustrating, designing, and making museum exhibitions and painting historical and modern subjects. He also finds time to write and do research. He has served as a historical consultant for exhibitions, museums, and even the odd film, and while his primary interest remains in history, he retains a lively interest in fantasy as well, consulting on director Peter Jackson’s epic movie trilogy The Lord of the Rings.

Military Heritage: How did you become interested in history? Was there one particular event that captured your imagination?

Gerry Embleton: I’ve always been interested in the past. I don’t see it as separate from the present and future. We all are what we are because of what’s happened to us, what our parents and grandparents were and did, and what sort of society we’ve grown up in. It’s totally inescapable, and even a slight knowledge of history shows how each generation or two repeats endlessly the same mistakes, and will doubtless do so until the end of time. We’ve made enormous technological progress, but none morally. War is still mankind’s main preoccupation.

MH: Growing up in a nation with a long military heritage and living during World War II with German planes coming over to bomb your city must have had some impact on your views of history as well.

GE: Like many children, I played knights, soldiers and explorers, cowboys and Indians, pirates and, of course, war. Myself, two older brothers, and my mother lived just outside London, on the Luftwaffe’s and the V-1’s flight path to the capital. Our grandparents lived in the East End of London, not far from London’s docks. My father was away in the army, four years of patching up wounded in Africa, Italy, and Greece. Overhead daily were vapor trails crisscrossing the sky. I was tiny, but clearly remember the wailing sirens, countless alarms day and night. On occasion there were more than 20 in 24 hours. The staccato banging of antiaircraft guns, thump and crash and sometimes enormous concussions, and the unforgettable gurgle of the engine of the V-1. We took cover in an Anderson shelter, a corrugated iron box half-buried in the back garden. My mother wrapped us in blankets and rushed us down to it when the sirens sounded. The shelter was damp and smelled musty, the air of burning. It was exciting to watch the searchlights cutting the night sky, the red glow on the horizon, the sky-flash of explosions. It must have been very hard for my mother. Many times during an alarm when it was too late to get to the shelter, she sat with us in a cupboard under the stairs. I suppose I felt the tensions and fears through my family, but I don’t remember them. For my two older brothers in their early teens, it was a huge adventure. We watched countless planes flying over. I remember one day particularly, scores of them going over, flying low, with white bands painted on their wings and everyone in the back gardens waving. D-Day? Arnhem? I’m not sure. So I grew up with vivid impressions of historical events and a family awareness of the effects of two world wars.

MH: It has been said that history taught in schools can be boring. How could history be made more interesting?

GE: My history master at school did his best to crush my passion and enthusiasm for history. Thankfully, my good old British bloody-mindedness kept the flame of interest alight. It’s amazing how such a potentially exciting subject is so often taught as if it is the dullest on earth.

MH: You’ve strived throughout your career to bring history to life, or at least to make it interesting. Where do you draw your inspiration and what sources do you use when you’re creating an illustration or 3-D model?

GE: I’ve been working on the interpretation of the past, writing, illustrating, and doing it three-dimensionally and “live” almost since I left school. I’ve learned that you must work with all possible sources and, if they can be found, the original sources. Tracking them down is fun but terribly time-consuming, and one needs easy access to a good library system. I have amassed a huge collection of reference books and folders containing documents, illustrations, photographs, archaeological reports, eyewitness accounts, and my own sketches and notes on surviving uniforms and equipment. But I’m very fortunate. I’ve worked with scores of specialists, experts in their fields who are generous with information. My work has opened doors to private and museum collections. Most people don’t have that chance, nor frankly do they have the passion and time. I’m actually paid to do it and I’ve learned who I can go to for help.

MH:You’ve illustrated more than 40 books for Osprey. Why do you think they’ve become so popular with collectors, modelers, and others with an interest in history?

GE: The Osprey series of books has brought an amazing volume of work to the public, relatively cheaply and easily purchased. I’ve worked for them on and off for years. Not every title is great. In such a large, far-ranging series involving many authors and artists, with a strictly limited budget and the demands of a competitive market, some failures are inevitable. But many of the titles are a good, solid foundation for future research, and some are simply the very best that’s available on a given subject.

MH: Considering that some of the subjects you and other artists capture in illustrations, or in the 3-D models, were never photographed, how do you keep the work accurate?

GE: What is accuracy? The dictionary says that it’s “faithful measurement or representation of the truth,” but how can we apply that to a historical event, a physical happening involving one or hundreds of people? “Eyewitnesses,” goes the cry. Well, that’s what we usually have to rely on. People see things differently. One may notice details, remember what was said but not the most important events; another grasps the tactics and movements but none of the details. At worse, they will contradict each other. They frequently don’t even see correctly what they’ve witnessed. The historian must take these conflicting accounts and any other information he can lay his hands on and write his own interpretation. But rarely do historians agree. Each may interpret the material differently … and so it goes on. It’s enormous fun, but often frustrating.

MH: How do you piece together a period uniform when you’re doing your 3-D models? Uniforms may have survived and there may have been regulations, but how do you know for certain how things were actually worn?

GE: I suppose that my ideal set of references for a uniform reconstruction would be (a) the dress regulations, (b) an account of what was actually worn by someone who wore it, (c) a sketch or photograph of it being worn, and (d) some surviving examples to study. Then you would still only have my interpretation, which might differ from Angus McBride’s or Don Troiani’s.

MH: How important are period photographs—from those eras when photography was available, of course—to an illustrator?

GE: Photographs as the only reliable source? Don’t you believe it. Photographs are also difficult to interpret without a thorough knowledge of other sources. Is the photograph captioned correctly? Many aren’t, by accident or design. Those famous Civil War photographs after Gettysburg showing the fallen of both sides at key spots in the battle are actually shots of the last few clusters of bodies to be buried, taken from different angles and falsely labeled. The photographers arrived too late to take picture of most of the field, and the burial parties had nearly finished

their work. Soldiers wore or held photographer’s props for their portraits. World War I and II pictures were labeled to suit the news headlines. German storm troops clearly exercising behind the lines become “Huns in Battle.” Battle scenes have been faked after the event. Nonregulation items of dress and kit appear. Were they really one-off exceptions put on just for the photograph, or common field adaptations?

MH: How do you view more modern sources, such as TV or film?

GE: Well, some certainly serve to create interest and even enthusiasm for the subject. A few present well-researched material pretty accurately, but far too many present the same old boring clichés, myths, and legends, with approximate costumes from stock and frequently unimaginative representations of battle scenes, crowds that look exactly like the 25 extras they had available. Too many use “low budget” as an excuse for low standards, the director’s lack of interest visible in every scene.

MH: Any examples that you thought stood out as particularly very good or very bad?

GE: The film Master and Commander was a brilliant interpretation, the feeling for historical accuracy and atmosphere masterful, and it was damn exciting, too. That’s historical film making at its best. The Sharpe’s series was good in a totally different way. Historically it was nonsense; it was dominated by reenactors in bad uniforms and every possible silly cliché about the British Army appeared. But it was fun, good to look at, and if you closed your historian’s eye it was enjoyable and certainly encouraged great interest in the subject. Apart from a fair number of 1950s B-movies, Braveheart gets my award for the worst historical film, with not two minutes’ worth of accuracy of story, basic morality, or costume, coming second only to the same director’s The Patriot, which I detested, because it was well made, good to look at, seductive but truly atrocious fictitious propaganda. Patriots of both sides committed many an unpleasantness during that early civil war, but no British troops ever filled a church with women and children and set fire to it. Far too many of my parents’ generation died fighting a war against a regime that did do that sort of thing, and many of us deeply resented this vicious distortion of the historical truth and that many viewers believed the tale. [Note: Mel Gibson, who starred in both films, directed Braveheart, but Roland Emmerich directed The Patriot.]

MH: Your company does some pretty interesting things. Rather than illustrations, these are basically life-size 3-D models. What eras have you recreated?

GE: Time Machine AG, that’s my own company that I set up in 1988 to make life-size, accurately costumed historical figures for museums. Since then we’ve made more than 60 exhibitions worldwide. We’ve covered many subjects and periods, from Bronze Age and Roman to pirates, Napoleonic, and the two world wars. From the very beginning I’ve tried to apply the highest standards of research and execution, and we’ve won a reputation for quality. We have two exhibitions currently running in the States.

MH: These aren’t just mannequins with replica uniforms standing against a white wall, either. What do you do to put these in a historical context?

GE: They are made as 3-D illustrations, the painting is adapted to the lighting, and we aim to create a pose that strikes the viewer as completely real. We get the uniforms and equipment looking right by making them out of the real materials. Buff leather is buff leather, brass is brass, and the textiles are as near the real thing as we can find. We study the cut of the clothes and all the tiny variations found on campaign—wear and tear, little repairs, and dirt of the same color as the geographical location. We have fun getting this right. The mud on our figure of the young George Washington actually came from the Fort Necessity battlefield.

MH:What are some of the exhibits you have done?

GE: Time Machine AG created a permanent exhibit with the sculptor David Hayes at the Frazier Historical Arms Museum, Louisville, Kentucky. Another exhibit entitled “Clash of Empires,” which brings together the finest collection of French and Indian War artifacts and paintings you are likely to see in one place, was done for the Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center. Dr. Scott Stephenson is the curator and much more. It has been a huge success. In fact, it’s received the American Association of State and Local History’s Award of Merit. It was an enormously enjoyable experience, working on some of my favorite subjects with a great team and a more or less free hand to recreate the models. I always judge the projects I work on by how much I learned doing them. This one rates first-class.

MH: You’re also involved in historical reenactments, which is another aspect of living history. How did you become involved in these?

GE: Well, to me it’s just another way to bring the past alive. How valuable is it? Well, it’s a tricky subject. I have played a part in medieval reenactment in Europe. I was a founding member and captain of the Company of Saynte George. We were refugees from other groups who wanted to go more deeply into the game. We had all played Hollywood medievals in our youth and needed something more challenging. Many of the participants who are visible in my two photo books are company members past and present. Some of the things we did were pretty well researched and executed. But reenactment is a difficult subject. Most participants want to enjoy playing in the past without too much effort. They have strictly limited budgets and have difficulty getting accurate references and reconstructions. Their fun comes from the company and comradeship, thickly mixed up with history. Others derive their pleasure from creating as accurately as possible clothes, uniforms, weapons—in fact everything they need—eating food, sleeping rough, trying to really experience another reality. Of course, both are having fun, both perfectly entitled to enjoy their different approaches. One can only judge them on how well they do whatever they claim to be doing. I think if you claim to present the past accurately, really “as it was,” you are claiming more that most reenactors can deliver.

MH: For your Time Machine AG models, do you use reenactors?

GE: No, I generally don’t use reenactors as models. Photographs of individuals with really good kit make very useful reference if everything is correct—cloth, cut, and details—but I usually adapt and change them. I know many historical artists these days do work closely from photographs of reenactors, but then it’s dangerous. You risk painting modern reenactment, not the past.

MH: You’ve done a lot of things in the historical context already, so what’s next?

GE: Well, I have future exhibition work and paintings on 18th-century North American subjects bubbling in the cauldron. I’m working on my own book on the Redcoats of the period. And figure-wise, I’d like to do something on Hogarth’s London, the common soldier’s daily life, the western front in World War I, which is another subject that’s interested me for a long time. Certainly more pirates and putting an entirely different hat on a classical fairy tale or fantasy subject. But I usually get enthusiastically involved in any subject that I work on. n

For more information on Gerry Embleton, visit his website: www.gerryembleton.com. More about Time Machine AG’s work may be found at www.time-machine.ch.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments