By Philip Burton Morris

The first truly realistic American films of World War II began with a flourish familiar to any moviegoing audience at the time: a hand-drawn company logo introduced by musical fanfare. That company, United News, was unquestionably the most prolific producer of films throughout American involvement in World War II. Between 1942 and 1946, United News released 267 newsreels, every one bearing the image of a fierce bald eagle, talons poised to shred, wings filling the screen. The newsreels were marvels of editorial ingenuity. Their assemblers, provided with a smattering of footage that varied wildly in quality and competence, made every 10-minute film a moving and compelling draft of contemporary history.

The newsreels, of course, presented a highly selective history. Their chief end was not to educate the audience but to motivate it—to buy war bonds, to receive the recommended weekly booster shot of patriotic fervor, to become further involved in the ever-unfurling narrative of the war. The newsreels ended with the prerequisite conclusion demanded of any American war film: victory. World War II was a constant fixture on movie screens, marking in 10-minute increments the development of an American movie genre as inexhaustible and structure-bound as the musical or the western. The newsreels taught the audience to crave the drama of complex warfare, and the war gave them the desired happy ending, an unequivocal triumph of American good over the forces of evil, as embodied unambiguously by the vicious minions of Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito.

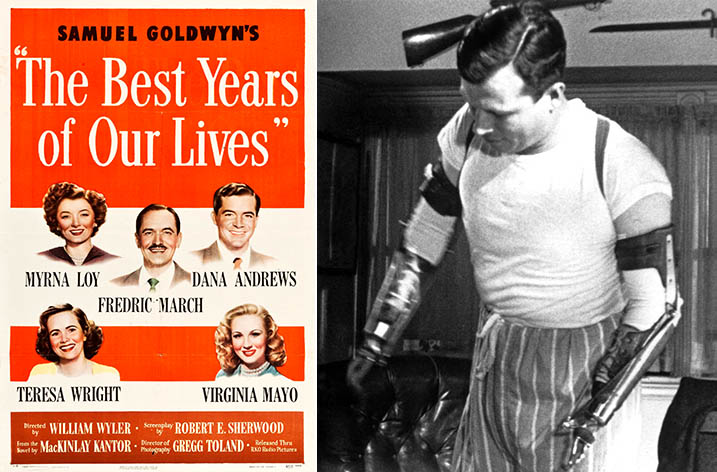

The Best Years of Our Lives

At the conclusion of the war, Hollywood studios wanted to continue selling movies to ticket-buying audiences that depicted the most vivid and involving experience in their national and personal history. The problem was how to keep viewers involved, now that the war was over and the soldiers had come home. In 1946, RKO Radio Pictures, still reeling from a protracted legal battle with William Randolph Hearst over the release of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane five years earlier, was happily surprised by the success of its film The Best Years of Our Lives, a deeply felt depiction of the postwar experiences of three carefully selected veterans—Army, Navy, and Army Air Force—returning home to their uncertain lives in modest Anytown, USA.

Two of the three primary performers were already established studio actors. Fredric March was comfortably in his second decade of starring parts, and Dana Andrews was reuniting with director William Wyler, who had given Andrews his first major role in 1940. But it was the third lead that really turned the tide of audience affections and made the movie a runaway hit. For the pivotal role of Midshipman Homer Parrish, RKO cast nonactor and wounded war veteran Harold Russell, a member of the 13th Airborne Division who had lost his hands to a mistimed explosive in a wartime training accident at Camp Mackall, North Carolina. Russell subsequently had been featured in the Army’s 1945 short documentary Diary of a Sergeant, a compassionate portrait of the challenges faced by maimed soldiers attempting to reintegrate themselves into civilian life.

Director Wyler saw the documentary and insisted that Russell be cast in the central role of Homer, whose war wounds gave him hooks for hands. The filmmakers tailored the Homer storyline to better fit Russell’s own life and injuries, and the sequences that centered on his anger and shame, most poignantly in his relationship with his devoted fiancée Wilma, had a maturity, restraint, and emotional honesty that were quite uncommon for a war film of the era. The professional actors surrounding Russell also did fine work, but Russell was the brave heart of the film and an icon to the many thousands of veterans who saw it. He was awarded a historic two Academy Awards for his performance: Best Supporting Actor and an honorary award “for bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans through his appearance in The Best Years of Our Lives.”

The Post-War Combat Film

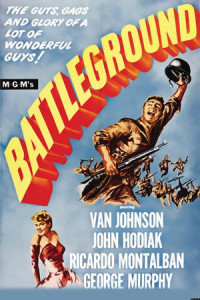

MGM’s Battleground (1949) was among the first World War II combat films to reinvigorate the form by challenging the pattern. Director William A. Wellman earlier had made the popular and successful The Story of G.I. Joe (1945), a partly fictional biopic of the war’s most famous war correspondent, Ernie Pyle. The differences in execution between the two films demonstrated the sudden leap forward in psychological complexity that occurred following the war’s end. Battleground, like its predecessor, focused sympathetically on the wartime experience of the common infantryman, but with a freshly imagined degree of precision and idiosyncrasy in the portrayal of the soldiers themselves. They were shown to be chronically beleaguered men who groused about being cold, going hungry, and huddling, weary and perennially threatened, in the freezing foxholes around Bastogne. The Story of G.I. Joe and other films made during the war seldom treated infantrymen with such specific realism, fearing that such realism might somehow besmirch the symbol of the idealized soldier.

MGM’s Battleground (1949) was among the first World War II combat films to reinvigorate the form by challenging the pattern. Director William A. Wellman earlier had made the popular and successful The Story of G.I. Joe (1945), a partly fictional biopic of the war’s most famous war correspondent, Ernie Pyle. The differences in execution between the two films demonstrated the sudden leap forward in psychological complexity that occurred following the war’s end. Battleground, like its predecessor, focused sympathetically on the wartime experience of the common infantryman, but with a freshly imagined degree of precision and idiosyncrasy in the portrayal of the soldiers themselves. They were shown to be chronically beleaguered men who groused about being cold, going hungry, and huddling, weary and perennially threatened, in the freezing foxholes around Bastogne. The Story of G.I. Joe and other films made during the war seldom treated infantrymen with such specific realism, fearing that such realism might somehow besmirch the symbol of the idealized soldier.

The exhausted but essentially sturdy and honorable men of Battleground were drawn with a crisp, irreverent eye for character detail (as with actor Douglas Fowley’s Private “Kipp” Kippton, whose false teeth were rarely in their rightful place). Such details elevated the film above the fidgety platitudes of similar pictures of the period. The primary creative team on Battleground drew from authentic recollections of infantry life. Director Wellman had served as a fighter pilot in World War I, and screenwriter Robert Pirosh had been a master sergeant with the 35th Division during the siege of Bastogne. Pirosh was determined to write a more realistic combat film by weaving private observations and memories into a reasonable facsimile of the Battle of the Bulge and merging the personal and factual into a more authentic combat memoir.

To a great degree, both director and screenwriter were successful. A groundbreaking achievement, Battleground established the confessional subgenre echoed by its portentous advertising slogan: “You … Or Someone in Your Family … Or Someone You Love … Wrote and Lived This Story!” Returned veterans saw themselves in the humanized characters of the besieged soldiers at Bastogne. The deaths of two of the unit’s main characters, played by appealing young actors Ricardo Montalban and Richard Jaeckel, further heightened the film’s realism for a viewing public that had suffered its own losses during the war.

To a great degree, both director and screenwriter were successful. A groundbreaking achievement, Battleground established the confessional subgenre echoed by its portentous advertising slogan: “You … Or Someone in Your Family … Or Someone You Love … Wrote and Lived This Story!” Returned veterans saw themselves in the humanized characters of the besieged soldiers at Bastogne. The deaths of two of the unit’s main characters, played by appealing young actors Ricardo Montalban and Richard Jaeckel, further heightened the film’s realism for a viewing public that had suffered its own losses during the war.

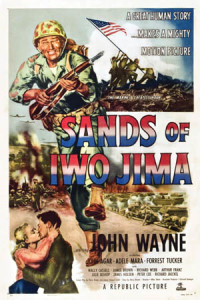

Realism in Sands of Iwo Jima

Released within months of Battleground, Sands of Iwo Jima further nudged the war genre toward Hollywood-style realism. It was sold to audiences with the voiceover claim, “These are your boys, who John Wayne as Sergeant Stryker forged into young men.” Sands of Iwo Jima freely deployed documentary elements in its battle sequences, a pioneering blend of Hollywood reenactments and actual Iwo Jima combat footage that established a new visual grammar for war films. The use of interpolated newsreels cannily reinforced the authenticity of newly staged action. Audiences remained especially credulous when documentary elements were present, which years of wartime exposure had trained them to be, and the enthusiastically responsive viewers made the film a top earner of the year.

![TITLE: BATTLEGROUND • PERS: JOHNSON, VAN / MURPHY, GEORGE / FOWLEY, DOUGLAS • YEAR: 1949 • DIR: WELLMAN, WILLIAM A. • REF: BAT019AB • CREDIT: [ THE KOBAL COLLECTION / MGM ]](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/m-War-Films21.jpg)

While still adhering to a Hollywood version of battle, Sands of Iwo Jima furthered the emergent vogue for realism by featuring the surviving real-life flag raisers Rene Gagnon, John Bradley, and Ira Hayes, who appeared onscreen just before the iconic flag-raising was reenacted for the camera using the original American flag flown atop Mount Suribachi. Sands of Iwo Jima is full of these strange juxtapositions between combat reality and movie reality, making the film a paradigmatic example of the ongoing development of realism in screen warfare. John Wayne’s Sergeant Stryker, sharing his sequences with both professional actors and real-life newsreel soldiers, seems to exist beyond the borders of the screen, barking orders that exist in both the past and the present. Battleground had imbued invented soldiers with lyric, believable brushes of personality, but Sands of Iwo Jima, despite a reversion to more standard character tropes, found a distinctive movie realism of its own, underscored by the death of the heroic Sergeant Stryker at the end of the movie.

A Mix of Genres

The nearly simultaneous success of Battleground and Sands of Iwo Jima reinvigorated Hollywood producers who had watched the profit margins of their earlier combat pictures shrink in the first postwar years. Audiences had not become exhausted by the topic (as studios had feared), but with the apparent narrowness of variation in the movies themselves. Studios increasingly began to combine World War II settings with stories from other genres to keep drawing in audiences that had tired of straightforward battle narratives. The 1951 publication of James Jones’s celebrated novel From Here to Eternity offered a new solution, a realistic character epic combined with elements of soap opera building toward the catastrophe of the now decade-old events of December 7, 1941. The book swiftly caught the attention of Columbia studio head Harry Cohn, who found its combination of romance and war, culminating in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, to be a fresh direction for World War II subject matter.

The nearly simultaneous success of Battleground and Sands of Iwo Jima reinvigorated Hollywood producers who had watched the profit margins of their earlier combat pictures shrink in the first postwar years. Audiences had not become exhausted by the topic (as studios had feared), but with the apparent narrowness of variation in the movies themselves. Studios increasingly began to combine World War II settings with stories from other genres to keep drawing in audiences that had tired of straightforward battle narratives. The 1951 publication of James Jones’s celebrated novel From Here to Eternity offered a new solution, a realistic character epic combined with elements of soap opera building toward the catastrophe of the now decade-old events of December 7, 1941. The book swiftly caught the attention of Columbia studio head Harry Cohn, who found its combination of romance and war, culminating in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, to be a fresh direction for World War II subject matter.

Author Jones, who had enlisted promptly upon turning 18, had been stationed at Schofield Barracks when the Japanese struck, and the novel, also set at Schofield, channeled his firsthand experience of barracks life with remarkable candor. In both the uncensored subject matter and the language used to illustrate it, From Here to Eternity went even further than its closest literary analogue, Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (published in 1948 and famously scrubbed of profanity by the nervous publisher), in staking out new maturity for the war novel. The barracks, brothels, boxing rings, and bars in which much of the story takes place are not hollow provocations designed to sell copies—although the book sold millions—but the practical trappings of enlisted men in Hawaii at the time. Jones’s influential book accurately depicted their prewar ennui and sullen minor controversies, leading toward the agonized catharsis that literally falls upon them out of a clear-blue sky on the morning when the peacetime soldiers suddenly become participants in a very real shooting war. From Here to Eternity was a reminder that America’s war had begun as an unprovoked intrusion on domestic life that ironically gave the directionless soldiers a larger sense of purpose.

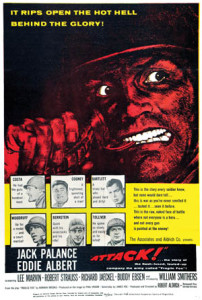

Few filmmakers of the 1950s were as fearless as Robert Aldrich in dealing with the postwar darkness that went along with warfare and veterans’ memories and feelings of guilt. In the mid-1950s, Aldrich resolved to make a war film devoid of the sentimental bromides that still clung to many of the combat movies being produced by the studios. Aldrich had hoped to make a film of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. Unable to buy the rights, Aldrich chose a lower profile 1954 stage play, Fragile Fox, set among frontline GIs in Belgium before and during the Battle of the Bulge, and commenced the picture without prior Army approval or assistance. Aldrich’s film, subsequently retitled Attack!, was a grim depiction of friendly fire and the vagaries of the military mind-set. Fragile Fox Company, under the leadership of a cowardly, bureaucratic captain, is slowly being decimated at the hands of German panzers. When the remaining soldiers are pinned down undetected in a basement below the German-overrun town, the captain senselessly volunteers to surrender and is murdered by his own men, who then watch in disgust as he is recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross by his corrupt successor. “It Rips Open the Hot Hell Behind the Glory!” screamed movie posters. “The Real Guts and Smell of Battle! This is the Story They Didn’t Tell—of the Heroes who Stood Up Under Fire, and the Few who Belly-Crawled Out!” Below the text, a pencil rendering in black and crimson depicted a soldier tearing the pin from a grenade with his teeth, a pulp image that was as stark as the film it advertised.

Few filmmakers of the 1950s were as fearless as Robert Aldrich in dealing with the postwar darkness that went along with warfare and veterans’ memories and feelings of guilt. In the mid-1950s, Aldrich resolved to make a war film devoid of the sentimental bromides that still clung to many of the combat movies being produced by the studios. Aldrich had hoped to make a film of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. Unable to buy the rights, Aldrich chose a lower profile 1954 stage play, Fragile Fox, set among frontline GIs in Belgium before and during the Battle of the Bulge, and commenced the picture without prior Army approval or assistance. Aldrich’s film, subsequently retitled Attack!, was a grim depiction of friendly fire and the vagaries of the military mind-set. Fragile Fox Company, under the leadership of a cowardly, bureaucratic captain, is slowly being decimated at the hands of German panzers. When the remaining soldiers are pinned down undetected in a basement below the German-overrun town, the captain senselessly volunteers to surrender and is murdered by his own men, who then watch in disgust as he is recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross by his corrupt successor. “It Rips Open the Hot Hell Behind the Glory!” screamed movie posters. “The Real Guts and Smell of Battle! This is the Story They Didn’t Tell—of the Heroes who Stood Up Under Fire, and the Few who Belly-Crawled Out!” Below the text, a pencil rendering in black and crimson depicted a soldier tearing the pin from a grenade with his teeth, a pulp image that was as stark as the film it advertised.

Kubrick’s War Realism in Paths of Glory

Kubrick’s War Realism in Paths of Glory

Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, released in 1957, was a vital work in the evolution of realistic war cinema. The film stood apart both for its subject—the court-martial of three French soldiers accused of cowardice in World War I—and also for its attitude of maximum cynicism. Kubrick, like Aldrich, resented the Hollywood tendency to baste even the most difficult subject matter in a rosy glow of audience reassurance, and his film was intended as a stern corrective to such contemporaneous candy-coated pageants of war as D-Day the Sixth of June and Between Heaven and Hell. Paths of Glory, like Attack!, is a scabrous indictment of a military engine it views as insane: controlled by proud despots with unearned decorations who order sane men shot for refusing to participate in a suicidal assault. The three soldiers tried and sentenced to death are chosen at random, sacrificial lambs offered up to deflect criticism from the mindless leaders who gave the impossible order. The film ends famously: after the execution of the soldiers, a group of their spared comrades shares drinks in a tavern on the eve of their return to the front, weeping quietly as they listen to a trembling young German woman sing a patriotic ballad on the small café stage.

WWII Comic Adventures

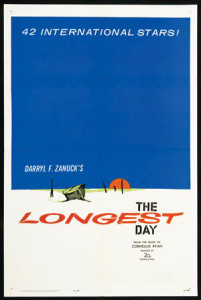

On the cusp of President John F. Kennedy’s brief Camelot-tinged administration, Kubrick’s film struggled to find an appreciative audience. Strong reviews did little to persuade the public that a fiercely unsentimental portrait of bureaucratic atrocity held entertainment value for the casual moviegoer. In the wake of Paths of Glory’s box-office failure, most genre films of the early 1960s reverted to the comforts of formula. Twentieth Century Fox spent $10 million on The Longest Day (1962), an expansive three-hour-long D-Day panorama that deployed four directors, five screenwriters (James Jones among them), 42 international stars, and thousands of background performers. Despite its large budget, the film still managed only one storytelling innovation: German and French characters spoke in their subtitled native languages. The enormous, highly touted cast is an almost constant distraction; producer Darryl F. Zanuck spared no opportunity to stop a battle sequence dead in its tracks for incongruous moments of slapstick, as when Sean Connery pratfalls into the water on Sword Beach during the D-Day landing, his famous eyebrows bouncing upward in hambone exasperation. The film is full of such heavy-handed juxtapositions. Determined to make the definitive war epic, Zanuck sabotaged his own efforts by turning serious history into low-browed comedy.

On the cusp of President John F. Kennedy’s brief Camelot-tinged administration, Kubrick’s film struggled to find an appreciative audience. Strong reviews did little to persuade the public that a fiercely unsentimental portrait of bureaucratic atrocity held entertainment value for the casual moviegoer. In the wake of Paths of Glory’s box-office failure, most genre films of the early 1960s reverted to the comforts of formula. Twentieth Century Fox spent $10 million on The Longest Day (1962), an expansive three-hour-long D-Day panorama that deployed four directors, five screenwriters (James Jones among them), 42 international stars, and thousands of background performers. Despite its large budget, the film still managed only one storytelling innovation: German and French characters spoke in their subtitled native languages. The enormous, highly touted cast is an almost constant distraction; producer Darryl F. Zanuck spared no opportunity to stop a battle sequence dead in its tracks for incongruous moments of slapstick, as when Sean Connery pratfalls into the water on Sword Beach during the D-Day landing, his famous eyebrows bouncing upward in hambone exasperation. The film is full of such heavy-handed juxtapositions. Determined to make the definitive war epic, Zanuck sabotaged his own efforts by turning serious history into low-browed comedy.

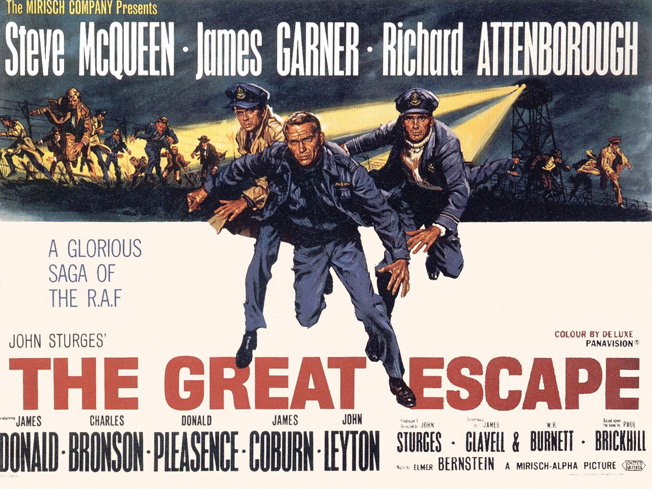

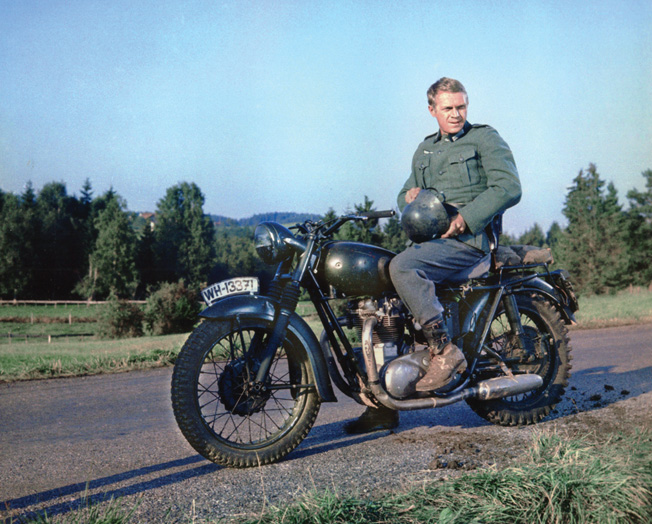

The Great Escape (1963), although an immensely entertaining caper film, had the dramatic heft of a chewing gum wrapper. Paul Brickhill, whose nonfiction book was the basis for the film, had experienced firsthand the planning of the Allied POW escape from Stalag Luft III that culminated in the summary execution by the Gestapo of 50 recaptured escapees. The film itself, although grimly true to the culminating massacre, is primarily a comic adventure, a heist picture whose wartime setting is used mostly to flavor the premise with greater prestige. The history-based elements decorate the Bavarian periphery, but it was Steve McQueen’s iconic (and entirely invented) motorcycle ride that most viewers tended to remember. His own escape attempt may have been foiled, but McQueen’s cocky and unbowed attitude at the close of the film allowed it to end on an audience-satisfying high note.

Depicting Vietman in WWII and Korean War Films

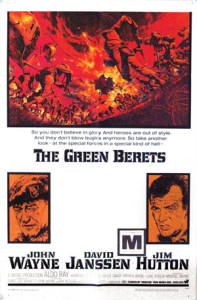

The years immediately following the shocking Kennedy assassination brought a temporary suspension of frivolous war pictures. Robert Aldrich returned to the genre in 1967 with The Dirty Dozen, a proto-counterculture paean to misfit individuality that proved hugely popular with audiences that were beginning to polarize along generational lines as the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War wore on. Studios were at a loss about how to portray the murky new conflict. John Wayne made an infamously pro-war attempt, The Green Berets, in 1968. A traditional-minded film about a decidedly nontraditional war, The Green Berets was a box office success but a critical failure; influential critic Roger Ebert called it “heavy-handed and remarkably old fashioned” and named it to his permanent “most-hated list.” The old verities, it seemed, no longer played so well—either on-screen or off.

The years immediately following the shocking Kennedy assassination brought a temporary suspension of frivolous war pictures. Robert Aldrich returned to the genre in 1967 with The Dirty Dozen, a proto-counterculture paean to misfit individuality that proved hugely popular with audiences that were beginning to polarize along generational lines as the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War wore on. Studios were at a loss about how to portray the murky new conflict. John Wayne made an infamously pro-war attempt, The Green Berets, in 1968. A traditional-minded film about a decidedly nontraditional war, The Green Berets was a box office success but a critical failure; influential critic Roger Ebert called it “heavy-handed and remarkably old fashioned” and named it to his permanent “most-hated list.” The old verities, it seemed, no longer played so well—either on-screen or off.

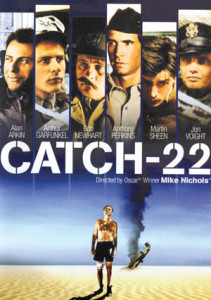

Two years later, director Mike Nichols, then a central figure of the New Hollywood movement, followed his epochal youth film The Graduate with an adaptation of Joseph Heller’s antiwar novel Catch-22, challenging John Wayne’s didacticism with a fashionably scatterbrained tragicomedy about war’s basic insanity. Although set in World War II, Heller’s legendary novel, published in 1961, was well tailored to outspoken opponents of the Vietnam conflict, who regarded the central paradox of the title phrase as a perfect signifier of misapplied military logic. The movie’s everyman antihero, Yossarian, played by the likable actor Alan Arkin, is caught in a trap all too similar to the trap then facing the United States in Vietnam: he can’t stay, but he can’t leave either. There seems no way out of the quagmire.

Nichols’s film was overshadowed almost immediately by Robert Altman’s hit movie M*A*S*H, an absurdist film set in the Korean War whose breakout popular success established the predominant tone for seventies war films—a flippant antiauthoritarian bravado that masked a deepening despair. Through the distancing device of its Korean War setting, M*A*S*H was able to comment mordantly on the human cost of the misguided war in Vietnam. Its harried surgeons and nurses, attempting to save lives amid the chaos of the battlefield and the entrenched insanity of military bureaucracy, represented an entire nation’s anguished attempt to make sense of an increasingly nonsensical war. They laugh to keep from crying.

Nichols’s film was overshadowed almost immediately by Robert Altman’s hit movie M*A*S*H, an absurdist film set in the Korean War whose breakout popular success established the predominant tone for seventies war films—a flippant antiauthoritarian bravado that masked a deepening despair. Through the distancing device of its Korean War setting, M*A*S*H was able to comment mordantly on the human cost of the misguided war in Vietnam. Its harried surgeons and nurses, attempting to save lives amid the chaos of the battlefield and the entrenched insanity of military bureaucracy, represented an entire nation’s anguished attempt to make sense of an increasingly nonsensical war. They laugh to keep from crying.

As the Vietnam War drew to an end, another series of World War II-themed films challenged the newfound prevalence of distrust in the military. Patton, Tora! Tora! Tora!, Midway, and MacArthur all premiered between 1970 and 1977, each attempting to soothe the psychic wounds the public had suffered from Vietnam by returning to the deeply satisfying well of the Good War, with its clear-cut battles and the mythic men who won them. The old standbys were dusted off for use—newsreel combat footage, the use of genuine Army equipment on loan in exchange for script approval, strict adherence to the established sequence of events. The new wave of throwback war movies enjoyed varying degrees of success with audiences and awards committees, culminating in Patton’s seven Academy Awards, including best picture and best actor (George C. Scott in the title role). The other films made little lasting impact on critics or audiences.

The Vietnam War Films

Concurrently, Vietnam was proving impossible for studios to package in the traditional manner. Accepted definitions of combat valor were suddenly up for debate, and the films set in Vietnam became highly allegorical, at times nearly abstract, studies of largely antiheroic characters. The new realism emphasized psychological accuracy; films set in the Vietnam War were to act as cracked mirrors of the war’s maddening realities. “My film is not about Vietnam,” Francis Ford Coppola famously declared in 1979 of Apocalypse Now, “my film is Vietnam.” The year before, both Coming Home and The Deer Hunter had made celebrated statements on the damage done to the post-Vietnam national psyche, each echoing an earlier World War II-themed blockbuster. Coming Home, a 1970s variant on The Best Years of Our Lives, focused on the readjustment of combat-wounded veterans. The Deer Hunter, in constructing a tableau of romance and tragedy, of men made restless by domesticity whose lives are interrupted—not altogether unwillingly—by war, recalled From Here to Eternity, but with a modernizing overlayer of disorienting violence and despair. Despite its somewhat racist subtext of villainous Viet Cong who are somehow more evil than their real-life models, The Deer Hunter was given an Academy Award for best picture of 1979.

Apocalypse Now, based loosely on Joseph Conrad’s novel The Heart of Darkness, had less critical success. Hallucinatory and doom-laden, from its first fiery images Coppola’s film exuded a clinical disinterest in the traditional mores of earlier war pictures. Amplified Wagner thunders from loudspeakers as American helicopters decimate villages to clear the nearby beach so that a bloodthirsty colonel can surf. Playboy bunnies offer bawdy consolation for soldiers taking fire from invisible enemies, as flares in every color of the crayon box streak the burning tree line. Senseless atrocity awaits Martin Sheen’s beleaguered Captain Willard at every turn as he moves nearer to his target, the deranged jungle demigod Colonel Kurtz, whom Willard’s Saigon superiors have marked for assassination. There is no solace in organized warfare; Willard regards his own mission as without righteousness or morality. There is only the endless river dividing the wildly growing jungle. Everything within the jungle is deadly—tigers, tribesmen, the Viet Cong, and finally even Willard himself. A singular achievement in impressionist filmmaking, Apocalypse Now was not, as Coppola claimed, Vietnam itself, but his feverish rendering captured certain surreal aspects of the war as no other film had yet done. “The Horror,” Kurtz’s term for the war and by extension the human condition itself, had never been more vivid or unhinged.

Oliver Stone’s Platoon, released in 1986, was equally seismic. The first ultra-realistic Vietnam combat film, Platoon was a plainspoken cry of pain on behalf of all veterans. Stone was himself a decorated infantryman, and his experiences from his tour of duty in Vietnam informed the elegiac intensity of the finished film, equally fierce and aching. When doom visits Stone’s soldiers, the abruptness and absence of a discernible pattern are jarring: the misstep of a rain-slick combat boot trips a bomb, a night detail brings paralysis for the lookout who spots approaching Viet Cong, platoon members go abruptly missing and turn up butchered days later. Stone imparts a central moral message that the war had been fought between opposite poles of the American character. More than a decade removed from the war’s conclusion, audiences found both Platoon and Stone’s 1989 companion piece, Born on the Fourth of July, cathartic. His films struck a resonant tone that attempted to reconcile the cultural wounds of Vietnam with the ragged honor of the young men who had fought and died there, and those who had come back home to a much different welcome than their GI fathers after World War II.

Advancements in CGI: A New Age of War Realism

The development of computer technology in the 1990s led to a large evolutionary leap in filmed depictions of modern warfare. Steven Spielberg’s 1998 movie, Saving Private Ryan, led the way. The famed opening D-Day sequence remains unsurpassed in ferocity and scope, a depiction of the chaos of warfare so authentic that stunned veterans of the landing who saw the film were reported to have wept at the display. The relentless onslaught of deafening bullets, drowning soldiers, and sudden death on all sides overwhelms the senses with absolute verisimilitude. Spielberg, working with the finest technical resources at his disposal, was immeasurably aided by the cinematography of Janusz Kaminsky, whose camerawork uncannily evokes the perilous improvisations of genuine combat newsreels. Spielberg’s achievement in Saving Private Ryan so elevated the standard of realism that every subsequent war film, from Black Hawk Down to The Hurt Locker, has unavoidably borrowed from that movie’s Normandy footage. After that initial burst of hell, Saving Private Ryan reverts to broad-brush portraits of the supporting cast of soldiers according to his respective accent or ethnicity, giving the movie a certain similarity to earlier World War II “buddy pictures.” There is the wisecracking Brooklynite, the taciturn southern hillbilly, the Jewish intellectual, the West Coast milquetoast, and the grizzled old sergeant. Star Tom Hanks’s reluctant hero, Midwestern Captain John Miller, would not have been out of place in a vintage wartime movie. A badly misconceived framing device involving an unnecessary prologue and epilogue somewhat mars the movie. But the unrivaled realism of the D-Day landings and the clanging sizzle of bullets striking home made Saving Private Ryan a watershed in realistic American war films.

The harrowing first decade of the new century further renewed American interest in World War II. For audiences there was renewed comfort in watching the familiar tales of winnable wars against visible enemies. In 2006, director Clint Eastwood bravely dissected this impulse with Flags of Our Fathers, his corrective history of the flag raisers at Iwo Jima. Eastwood’s war sequences betray the inescapable influence of Saving Private Ryan, but his narrative poses questions more insidious and difficult to answer than those of Spielberg’s film. Although Bradley, Gagnon, and Hayes are branded as heroes by an eager press corps, their victory tour is plainly a publicity ruse to sell more war bonds. The three men, with varying degrees of acceptance or resistance, recognize this. They reenact the raising of the flag in public squares and on baseball fields, a ritual they wearily perform for a war-weary public to reenergize the patriotic base.

Six years after Eastwood’s film, the symbolic value of Joe Rosenthal’s photograph continues to be used on Army recruitment billboards. It endures as the most famous image of World War II and one of the most famous in all American history. The image contains the true weight of that history, a history Hollywood filmmakers helped shape, dramatically and aesthetically, even for those who had actually lived through it. For nearly 70 years filmmakers have sought to depict in their war films a small measure of that perfect iconic moment at Iwo Jima: the angled limbs of the soldiers, unposed but glowing with accidental perfection, the smudged pencil-lead austerity of the sky, the stoic rigidity of the flagpole, and the impeccable ripple of the American flag itself, unfurling triumphantly for all eternity. Flags of Our Fathers has Rosenthal shrugging as he casually snaps his immortal picture—maybe with luck, he thinks, the undeveloped image will be worth printing. Eastwood’s film, all these years later, cannot totally recapture the accidental magic that Rosenthal caught on Mount Suribachi, but the transcendent moment remains burned into the collective psyche of Americans, stubbornly resistant to revision, seven decades removed from the nation’s last Good War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments