By Allyn Vannoy

On February 23, 1942, one month after Rabaul had fallen to the Japanese, six B-17s of the U.S. Fifth Air Force, flying out of Townsville, Australia, launched the first Allied air strike against the new enemy stronghold on the northeastern tip of New Britain, just east of New Guinea. The campaign against Rabaul would prove to be one of longest of the war, lasting until August 1945. The skies over such places as St. George’s Channel, Blanche Bay, and Gazelle Peninsula would witness one of the most bitterly fought campaigns of the Pacific air war. The overriding objective of the Allied campaign was to capture or at least neutralize the key Japanese base, whose geographic position made it the hub of the enemy’s formidable air-base system at the southeastern corner of their recently won empire.

In early 1943, the Japanese prepared their new garrison to meet the anticipated Allied onslaught. The Eleventh Air Fleet at Rabaul mustered about 300 planes and 10,000 men, including approximately 1,500 air crewmen. Land-based naval air units in quiet sectors of the Pacific were heavily scavenged for additional planes and pilots. As a backup, two Japanese carrier air groups with another 300 planes were positioned at Truk, and flight operations at forward bases in the Solomons were sharply curtailed to conserve aircraft and crews. Defenders strengthened and expanded aircraft blast barriers and disposed antiaircraft guns in depth. When completed, Rabaul’s formidable air defenses included 260 AA guns ranging in size from 13mm machine guns to 127mm cannons.

On the Allied side, combat operations called for the use of all land-based aircraft in the Solomons, including the 1st and 2nd Marine Air Wings, the Army’s Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces, Navy land-based planes, and two squadrons each of bomber-reconnaissance aircraft and fighters of the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). Air assets were organized into three functional task groups: Fighter Command, directing escort and interceptor aircraft; Strike Command, with dive and torpedo bombers and short-range reconnaissance aircraft; and the Army Air Force’s medium and heavy bombers, directed by Bomber Command.

The Allied seizure of Guadalcanal and Buna-Gona, New Guinea, in early 1943 set the stage for the beginning of a coordinated offensive against Rabaul—code-named Operation Cartwheel. The taking of the Russell Islands by American Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s forces on February 21 marked the opening move of the drive. Construction was begun on Banika of an airdrome for fighters and medium-range bombers to support operations in the central and northern Solomons. The Allied fighters—Marine F4U Corsairs, Army P-40 Warhawks, and P-38 Lightnings—flying out of Guadalcanal, conducted sweeps into the northern Solomons on a regular basis. Strike Command sent a steady stream of SBD dive bombers and TBF torpedo bombers to hit Japanese positions at Munda and Vila. Such operations kept Rabaul’s 300-plane garrison from launching major raids of its own on the swelling American complex at Guadalcanal. (On April 18, American pilots claimed their most important victim when they intercepted and shot down a plane carrying Japanese naval commander in chief Isoroku Yamamoto on an inspection flight from Rabaul to Bougainville.)

Allied raids on Buin-Kahili and the Shortland Islands increased appreciably after airfields in the Russells became operational. In an effort to counteract the Allied activities, the Japanese Combined Fleet transferred 58 fighters and 49 bombers from Truk to the Eleventh Air Fleet on May 10, with the intent of hitting at the Allies’ main strength—their fighter planes. On June 7, approximately 70 Zekes headed for the Russells. Warned by friendly coast watchers, Fighter Command scrambled 104 fighters to intercept. In the subsequent 90-minute air battle, the Japanese were turned back with the loss of 23 planes. Allied losses were seven fighters, with all but one pilot successfully recovered.

Five days later the Japanese sent 77 fighters south again, only to be intercepted north and west of the Russells by 49 Allied planes. Some 25 Japanese planes failed to return, against the loss of six Allied fighters. Despite these losses, the Japanese launched another strike on June 16, with 24 Val dive bombers and 70 fighters. Again warned by coast watchers and vectored into position by New Zealand ground interceptor radar, 74 planes of Fighter Command challenged the Japanese planes. Six Allied fighters were destroyed in the ensuing dogfight, and Japanese losses again were heavy. Those bombers that managed to reach Guadalcanal were quickly shot out of the sky.

Less than a week later, Marine raiders were landing on Segi, heralding the drive to seize the Munda airfield. To meet this new threat, the Japanese threw every available plane into the fight, sending 150 Zekes, Vals, and Kate torpedo bombers of the Second Carrier Division from Truk to the base at Kahili. While this move strengthened Rabaul, it greatly crippled the offensive power of the Japanese Combined Fleet.

Two Allied fields at Banika became fully operational in late June, and B-25 Mitchell bombers made their first appearance flying against targets in the northern Solomons. After Allied reconnaissance spotted a large concentration of enemy shipping off Buin, a strike was mounted on July 17, led by seven B-24 Liberator heavy bombers, followed by 37 SBDs and 35 TBFs escorted by 114 fighters. Japanese Zekes rising from Kahili to intercept the attack were gunned down by pouncing Corsairs, with the Allies claiming 47 Zekes and five float planes. Avenger and Dauntless crews also sank the destroyer Hatsuyuki and damaged three other ships. American losses consisted of one SBD, one TBF, two Army P-38s, and one Corsair. To reinforce this painful lesson in air superiority, the Allies struck again on the 18th, causing considerable damage to Japanese shipping.

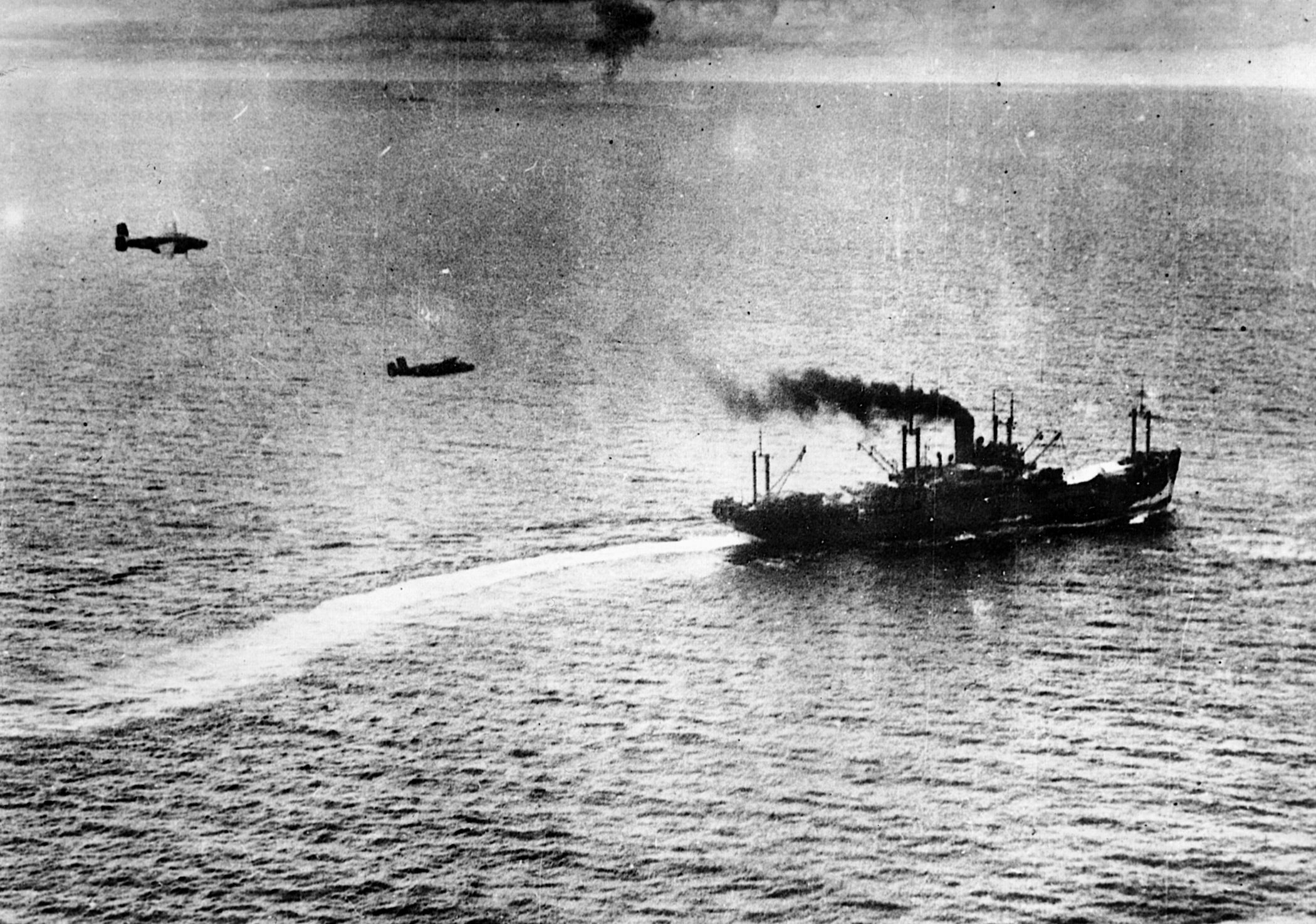

On the evening of June 19, a Black Cat PBY flying boat on patrol picked up a Japanese task force off Choiseul, allowing Strike Command to dispatch from Henderson Field six TBF Avengers armed with 2,000-pound bombs. Coming in “on the deck,” they sank the destroyer Yugure and damaged the heavy cruiser Kumano. Additional strike aircraft were launched, and at daylight a wave of skip-bombing B-25s sent the destroyer Kiyoami to the bottom. Two days later, a shipping strike by 12 B-24s, 16 SBDs, and 18 TBFs supported by 122 fighters caught and sank the seaplane tender Nisshin off Bougainville, along with its cargo of 24 medium tanks and 600 troops.

When Munda airfield fell to the Americans in early August, the Japanese realized that the only reason to continue the fight in the central Solomons was to buy time to strengthen their Bougainville defenses. By the end of the summer it was apparent that the empire’s vast outer defense perimeter would soon collapse. Imperial headquarters ordered commanders to hold out as long as possible so that a cordon of strategic defenses could be constructed from the Marianas through the Palaus and western New Guinea to the Philippines, in effect conceding the eventual loss of Rabaul along with other garrisons in the northern Solomons, the Bismarcks, and eastern New Guinea. Troops and matériel were retained on New Britain and New Ireland in the belief that a showdown for Rabaul was inevitable.

American General Douglas MacArthur was convinced that Rabaul would have to be taken on the ground, but the planners at Allied headquarters were not. These planners believed that Rabaul could be bypassed and neutralized by aerial blockade. The troops, ships, and planes needed for its capture could better be allotted to other operations. But while the Joint Chiefs were trying to determine how best to neutralize Rabaul, MacArthur’s staff was preparing plans for offensive operations that would follow landings at Bougainville and Cape Gloucester and complete Rabaul’s encirclement. A tentative target date of March 1, 1944, was set for the seizure of Kavieng and the Admiralties. The establishment of Allied airfields at Finschhafen and Cape Gloucester meant that the landings on the Admiralties could be covered by land-based fighters, but the Kavieng operations would require carrier air support since fighter planes from Cape Torokina on Bougainville would not be enough to provide effective escort and combat air patrols.

Once the Central Pacific offensive got under way with operations in the Gilbert Islands, mounting demands on the Pacific Fleet’s shipping resources determined that landings at Kavieng would have to be put off until May 1. Faced with the possibility of a six-month pause between major operations, Halsey consulted with MacArthur, who gave his approval to an intermediate operation that would keep the Allied offensive rolling, provide another useful base, and keep the pressure on the Japanese. Several islands were considered for the next objective. There was a proposal to seize a foothold in the Tanga Islands, 35 miles east of New Ireland, but it was rejected because the operation could not be effectively covered by land-based fighters. The capture of enemy airstrips at Borpop or Namatami was discarded because carrier support, as well as a large landing force, would be required. Finally, Nissan, the largest of the Green Islands, was determined to be close enough to Torokina for fighter support. Located 37 miles northwest of Buka and 55 miles east of New Ireland, Nissan atoll had room for a couple of airstrips. However, with Rabaul only 115 miles away and Kavieng another 100 miles beyond, the island was vulnerable to a Japanese counterattack.

While Halsey ordered his staff to prepare plans for the seizure of Nissan, he also directed them to study the possibility of seizing Emirau Island in the St. Matthias group as an alternative to Kavieng. As Allied bases at Segi, Munda, Ondonga, and Barakoma became operational in August and September, forward Japanese fields became untenable. In an effort to deal with Japanese bases at the southern end of Bougainville, Strike Command sent nearly 100 planes a day during the last two weeks of October to conduct bombing and strafing.

The first direct blow against Rabaul was struck on October 12, in support of landings on Bougainville. A major Allied strike was launched that included 87 B-24s, 114 B-25s, 12 RAAF Beaufighters, 125 P-38s, and 11 weather and reconnaissance aircraft. The 32 Zekes that rose to meet them were quickly overwhelmed. The Mitchells came in first, flying low over the water as they approached the Japanese base. Nine squadrons of B-25s in waves, some flying wingtip to wingtip and protected by P-38s, roared in to strafe the airfields. Their eight forward-firing machine guns blazing, the American planes dropped clouds of 20-pound “parafrag” bombs in their wake (these fragmentation bombs had parachutes to increase drag, thus providing a safe distance between the low-flying plane and the detonating bombs). Beaufighters struck at shipping in Simpson Harbor, Rabaul’s anchorage, followed by Liberators carrying six 1,000-pounders each. Allied losses for the raid were five planes, including two B-24s. Strike results included one 6,000-ton Japanese transport sunk and three destroyers damaged.

Weather delayed the next raid until the 18th, when 54 B-25s flashed in under a 200-foot cloud ceiling to hit enemy airfields and shipping. Additional 100-plane raids were carried out between October 23 and 29. Exaggerated and contradictory reports painted an unclear picture of the damage inflicted, although only five Allied planes were lost.

Australian and American ground forces steadily drove the Japanese back from coastal and inland positions on eastern New Guinea’s Huon Peninsula, while the 3rd Marine Division seized a foothold on Bougainville at Cape Torokina on November 1. The next day, reconnaissance aircraft found clearing skies over Rabaul, a harbor jammed with ships, and airfields holding 237 planes. Eighty B-25s and 80 P-38s were routed to the targets. Two squadrons of Lightnings led a sweep of the harbor, followed closely by four squadrons of Mitchells that strafed antiaircraft positions. This suppression attack opened the way for 41 B-25s. Attacking through a swarm of Japanese fighters, the Mitchells dropped to mast-top level, skip-bombing and strafing the desperately twisting and dodging ships. Japanese cruisers and destroyers responded with their heavy guns, sending up towering columns of spray in the path of the attacking planes, while batteries of antaircraft guns fired without letup. The Allies sank two cargo ships and a mine sweeper, along with a 10,000-ton oiler. The Japanese reported losing 20 planes, while Allied losses were eight B-25s and nine P-38s. The commander of the Fifth Air Force, Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, reported that the Japanese “put up the toughest fight the Fifth Air Force encountered in the whole war.”

The intensity of the fighting increased with the arrival of 173 planes from the Japanese Combined Fleet’s 1st Carrier Squadron, Third Fleet. The transfer of these valuable assets was a major gamble as it immobilized carrier forces at Truk to check the Allied advance into the northern Solomons. The Japanese christened the effort Operation Ro. The Third Fleet’s Zekes, Vals, and Kates were about to be caught in a three-way squeeze by planes from Allied airfields, American carriers, and the Fifth Air Force.

On November 5, American carrier-borne aircraft struck Rabaul for the first time. In an effort to counter landings on Bougainville, the Japanese had dispatched six heavy cruisers to Rabaul. This presented a major problem for the Allies since their own cruisers and destroyers were not yet available, still refitting after action off Cape Torokina. Halsey considered the threat posed by the Japanese heavy cruisers as “the most desperate emergency that confronted me in my entire term as ComSoPac.” Although it was expected that the “air groups would be cut to pieces,” the carriers Saratoga and Princeton were ordered to attack the warships collecting at Rabaul.

The task force launched a maximum effort with 52 F6F Hellcats, 23 Avengers, and 22 Dauntless dive bombers attacking 40 to 50 Japanese vessels in the harbor. As the bombers turned to attack, the Hellcats moved to ward off 70 interceptors. As soon as the Dauntlesses dropped their bombs, the Avengers cut in among the ships. Antiaircraft fire was fierce. One cruiser fired its main battery in an effort to knock down the TBFs that dogged it. American losses were surprising light: five F6Fs, four TBFs, and one SBD. Four of the heavy cruisers were crippled, three severely, and two light cruisers and two destroyers were also hit. The Japanese command reacted by withdrawing their heavies to Truk. The threat to Bougainville had been turned back.

On November 11, the Allied one-two-three combination hit again, despite poor weather. This time B-24s from both the Fifth Air Force and the Solomons participated, but the bulk of the raid was carried out by 239 aircraft from five carriers. One enemy destroyer was sunk and a light cruiser and destroyer were damaged. Following the strike, the Japanese located one of the American carrier groups and dispatched a counterstrike of 67 Zekes, 27 Vals, 14 Kates, and a handful of Betty twin-engine bombers. Marine Corsairs and Navy shore-based Hellcats intercepted the attackers, claiming 15 shootdowns.

The following day, planes of the Japanese Third Fleet were ordered to return to Truk, ending Operation Ro. In less than two weeks, the 1st Air Squadron had lost 43 of 82 Zekes, 38 of 45 Vals, 34 of 40 Kates, and all six of its reconnaissance aircraft. The Eleventh Air Fleet conceded the fight for Bougainville. A lull ensued as both sides prepared for the next round in the air campaign. The Allies were not completely idle as they readied fields on Bougainville and struck at barge traffic sailing from Rabaul to garrisons in the Solomons. Japanese air operations became increasingly dangerous for their pilots—Bettys on reconnaissance were shot down with such regularity that patrols had to be curtailed. Without such patrols, the Japanese had to rely on radar stations to provide Rabaul with a 20- to 60-minute advance warning.

Meanwhile, marauding Allied fighters continued to make inroads into Japanese strength. Even their latest-model Zekes were no match for the advanced American Corsairs and Hellcats. The Japanese pilots realized that they were engaged in a losing battle, but they fought on despite a sense of impending doom. The Japanese waited apprehensively for the Allied airfields on Bougainville to be completed, knowing that their completion would signal the climax of the air assault on Rabaul. On December 10, the field at Torokina became operational and Allied fighter sweeps were readied.

On December 17, the first sweep was made with 31 Corsairs, 23 Hellcats, and 23 RNZAF Kittyhawks. The New Zealanders made the first contact with 40 Japanese fighters climbing from the fields around Rabaul, downing five enemy planes during the engagement, at a cost of three of their own P-40s. All together, some 70 Japanese fighters took off, but few were able to climb up to the 25,000-30,000-foot level where the Corsairs and Hellcats waited like circling birds of prey.

The second sweep, on December 23, produced even better results for the Allies. This time the fighter force was held to 48 planes in order to tempt the Japanese to counterattack. As the sweep group arrived, it encountered 40 Zekes chasing the retiring bombers. The Allied fighters tore into the interceptors, claiming 30 at the price of three F4Us, three escorting F6Fs, and six bombers. Twenty-four hours later the pattern was repeated. This time the Liberators were escorted by P-38s and F4Us that knocked down six Zekes, while the follow-up fighter sweep of P-40s and F6Fs accounted for 14 enemy fighters with the loss of seven of their own.

Although MacArthur indicated on December 20 that the possession of airfields at either Kavieng or Emirau would accomplish his mission of choking off Rabaul, he soon returned to his belief that the New Ireland base had to be captured. Turning up the heat, the Allies began throwing alternating bomber strikes and fighter sweeps around the clock at the Japanese. Allied crews claimed 74 Japanese planes shot down between Christmas and New Year’s Day. Meanwhile, Navy Seabees prepared the Piva bomber field at Torokina for SBDs and TBFs and a field on Stirling Island for B-25s. Planes from the carriers Bunker Hill and Monterey struck at Kavieng on December 25, January 1, and January 4, but with minimal results.

While daily Liberator raids and fighter sweeps were conducted, three squadrons of RAAF Beauforts struck the Japanese fields at night. The Australians used their planes in a fashion that provided constant harassment, sending in a single bomber at a time, one after another, throughout the night. A period of bad weather broke on January 9, and 69 fighters escorted 23 SBDs and 16 TBFs on a strike of the main Rabaul fighter field at Tobera. Forty Zekes engaged the escort fighters as the SBDs concentrated on antiaircraft positions and TBFs followed, dropping 2,000-pound bombs on runways and aprons. Thirteen Japanese planes were claimed by the escorts, which lost a Hellcat and two Kittyhawks in return.

Japanese desperation showed as interceptors followed the SBDs and TBFs into dives, braving their own ack-ack fire. Fending off the Japanese fighters that broke through high and medium cover was the job of the RNZAF Kittyhawks. Flying close cover for the bombers, the New Zealanders braved the storm of flak, guarding the tails of the SBDs and TBFs as they streaked for home. Despite the diversity of Allied plane types and pilot nationalities, air discipline was well maintained.

The Allied air campaign attempted to choke off the Japanese supply network, stopping matériel from reaching Rabaul and bases in the Solomons. During January 1944, Strike Command sank seven merchantmen and an oiler and damaged three other ships, the TBFs approaching at 30 to 40 feet off the water and using one-ton bombs with delayed fuses. As the tempo of Allied attacks increased, the pilots noted a falling off in the number of Japanese interceptors. The intensity of the Allied offensive had convinced the Japanese to commit the 2nd Air Squadron, denuding the carriers Runyo, Hiyo, and Ryuho of their air groups to add 69 fighters, 36 dive bombers, and 23 torpedo bombers to the Eleventh Air Fleet. Throughout the month, the Allies conducted 1,850 sorties over Rabaul, with the loss of 65 planes. Estimates of Japanese aircraft losses varied greatly, but the damage was telling. They had no effective response to the Allies’ relentless attacks. There were not enough fighters to slow the pace, much less turn the momentum. Those that were available were outclassed by newer and better Allied aircraft and well-trained air crews.

At a coordinating conference on January 27, at Pearl Harbor, preparations went ahead for a simultaneous assault on Kavieng and the Admiralties. A new target date of April 1 was set, six weeks after Allied forces were slated to secure the Green Islands. In an admission of Allied superiority, Japanese fighter pilots were ordered “to attack or defend yourselves only when the battle circumstances appear particularly favorable to you.”

As bad as January was for the Japanese, February was worse. By early February, the Allies were putting up 200 planes a day. Concurrent operations in the Southwest and Central Pacific made Rabaul increasingly untenable. Halsey prepared to move New Zealand ground forces into the Green Islands. To support the operation and to provide cover for a pending carrier attack on Truk, the bombers of the Fifth Air Force began a series of large-scale raids on Kavieng on February 11.

The noose was tightening around Rabaul, and the Japanese knew it. The Kavieng raids and the anticipated invasion of the Admiralties forced Japanese air commanders to consider withdrawing from Rabaul. The final nail in the coffin was a series of carrier-borne air attacks on Truk on February 17 and 18 by Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance’s Central Pacific task forces. Planes from nine carriers hit airfields and shipping in the atoll’s anchorage. At least 70 Japanese planes were destroyed, along with 200,000 tons of merchant shipping, two cruisers, and four destroyers. Many of the planes destroyed had been destined for Rabaul.

The raid emphasized the futility of Rabaul’s further defense. The base’s strategic value had lain in its ability to shield Truk. All serviceable aircraft were now ordered from Rabaul to western New Guinea, the Palaus, the Marianas, and the Volcano-Bonins Islands. On the night of February 17-18, five American destroyers shelled Rabaul, proving its final vulnerability. Leaving behind some 30 damaged fighters on February 20, an estimated 70 to 120 Japanese aircraft escaped. The Japanese had conceded control of the air over Rabaul, losing at least 250 planes against about 150 Allied aircraft. While Allied losses could be quickly replaced, the Japanese pool of trained, experienced pilots was starting to run dry. Rabaul’s defenders, using two merchant ships, made a last-ditch attempt to save the valuable ground crew personnel. Allied bombers sank both vessels on the 21st.

But the conflict was not over yet—the Japanese garrison dug in to await an amphibious assault. Nissan atoll, in the Green Islands, was seized by the 3rd New Zealand Division on February 15. MacArthur, commenting on the operation’s success, said that it “rings the curtain down on [the] Solomons campaign.” Seabee units had the island’s fighter field operational by March 4. Three days later, Allied fighters staged an attack on Kavieng.

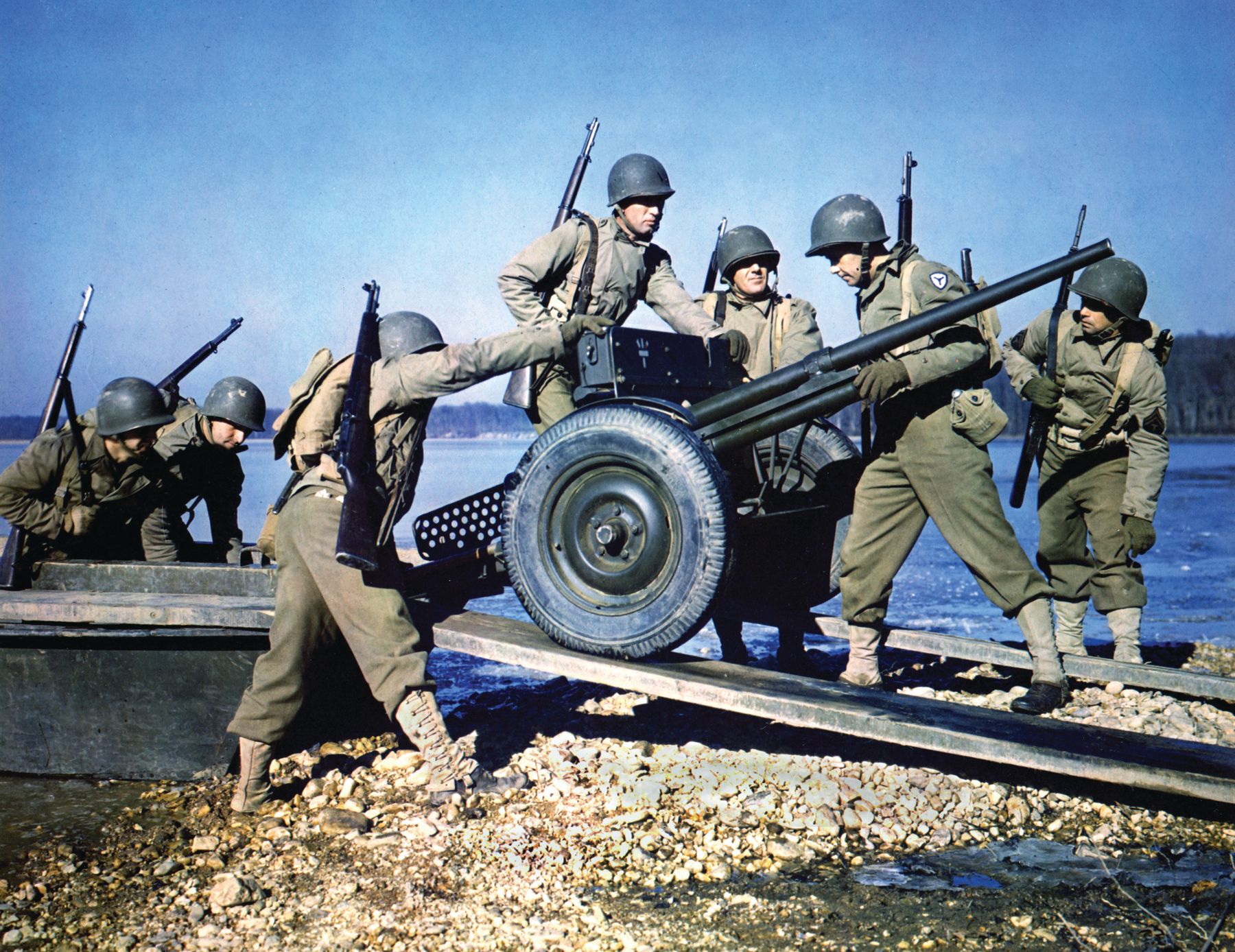

The Admiralties, north of Rabaul, represented the last link between Rabaul and New Guinea. Japanese-built airfields on Manus, the largest island of the group, and on Los Negros were captured by the 1st Cavalry Division after bitter fighting on March 15. While the battle raged, naval construction battalions and Army engineers worked on the airfields and naval facilities. Momote was operational by March 7. Manus grew into an important staging area supporting Allied operations during the rest of 1944. The islands’ Seeadler Harbor provided everything that Rabaul might have done, creating a complex that became a key staging base for the forthcoming Leyte landings and the drive on New Guinea’s coast.

While MacArthur planned to capture Kavieng, Halsey believed that another bypass operation was in order, and that the seizure of Emirau would provide a quick and cheap alternative to neutralize Kavieng and complete the isolation of Rabaul. The island of Emirau, 90 miles northwest of Kavieng, was considered a good site for a base. Eight miles long, the island was in the southeastern portion of the St. Matthias Group. On March 20, the 4th Marine Regiment stormed ashore, and construction battalions quickly went to work building facilities and an airfield. On April 9, advance elements of a Marine air group began arriving. In the next two weeks Marine fighter, dive, and torpedo bomber squadrons moved up from Bougainville and Nissan. By mid-May, Emirau was a fully operating partner in the ring of Allied bases surrounding Rabaul.

The Japanese base had no respite from attack. By April 20, after two weeks of bombing, only 122 of Rabaul’s 1,400 buildings remained standing. As Army and Marine fighter-bombers reduced the town to rubble, bombers laid waste to two large supply dumps. Around-the-clock operations gave the Japanese little chance to rest. Nighttime raids were conducted by Marine PBJ squadrons as they sent in one plane after another all night long.

A monotonous pattern of attacks went on day after day, with many pilots getting their first taste of combat against the Japanese bases. Operations included combat air patrols, milk-run bombing, and night heckling raids. As the number of targets decreased, the Allies conducted areawide “blast and burn” operations. When fighters became badly needed at Leyte to protect Allied shipping, Marine Corsairs were ordered up in December. The burden of maintaining the aerial blockade fell on RNZAF Corsairs and Venturas and four squadrons of Marine PBJs. In July 1945, the RNZAF took over direction of the campaign.

On August 9, 18 Marine PBJs flew the last bombing mission against Rabaul—three years, five months, and 17 days after the first bombs had been dropped on the base. When the Japanese surrender finally came, more than 130,000 Japanese were still isolated in the Bismarcks, Solomons, and eastern New Guinea. One of the key elements of Allied success had been a high degree of interservice and inter-Allied cooperation. The separate services had shown they could operate together as a team, applying bone-crushing tactics that eventually ground Japanese naval air power into the dustbin of history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments