By Christopher Miskimon

The sunrise on February 16, 1944, dawned foggy over the Via Anziate—the only highway between Anzio and Rome. Overnight, the 45th Infantry Division’s 2nd Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment (2/157), had advanced to take positions on the west side of the roadway, assuming its place on the front lines.

Company E, commanded by Captain Felix Sparks, sat at the right flank of the battalion’s line, where it bordered the division’s 179th Regiment. Looking out across the muddy ground in front of his position, Sparks saw overcoat-clad figures moving, but could not tell who they were. He called his higher headquarters and asked if the soldiers of the 179th were wearing overcoats. They weren’t, a voice on the radio replied.

“Those are Krauts coming after us,” Sparks told his men. Behind the enemy infantry, the sound of tank engines echoed through the chill morning air. It wasn’t long before enemy artillery began pounding Company E’s foxholes. Shells landed for 10 solid minutes, but the troops were so well dug in that casualties were light.

When the barrage lifted, three German panzers, unsupported by infantry, came forward and attacked. “They made a mistake,” Sparks said. Company E had the support of an antitank gun and two M10 tank destroyers (TDs). Sparks yelled to the TD commander, “Get ‘em!”

For a moment, the M10’s commander sat confused. “Are those British tanks?” he asked. A British division was dug in a few miles east.

“Hell, no—they’re German tanks!” Sparks shouted, and the TDs wasted no more time. They opened fire and quickly knocked out two of the panzers. Both exploded under the concentrated American fire, pieces of them flying across the battlefield; the third made a fast retreat. One of the M10s moved just then; Sparks figured the crew wanted a better field of fire. The movement exposed it to enemy view, however, and a German armor-piercing round crashed into the thinly armored TD. It burst into fast-spreading flame, forcing Sparks to abandon his foxhole and find another.

Almost immediately, German infantry attacked. Sparks’ men mowed them down. “We killed every damn one of them,” he later recalled. He thought the Germans might be drunk; they shouted as they ran awkwardly across the muddy ground. A few made it to E Company’s foxholes but were quickly cut down, tumbling into the mud in their gray overcoats. The sound of firing could be heard coming from the 179th’s lines; the enemy was attacking there as well.

Only half an hour passed before the third German wave attacked E Company. This time, the infantry came with armored support. “That’s what killed us,” Sparks said, referring to the mutual support of tanks and infantry. The panzers moved up to point-blank range and opened fire, blasting the American foxholes.

As E Company fought to hold back the enemy assault, Sparks saw a crewman from one of the tank destroyers climb atop the vehicle and man its .50-caliber machine gun, exposing himself to enemy fire. This sergeant even tied himself to the gun using a leather strap the crews used to lean against when firing at enemy aircraft. The machine gun roared, sending long bursts of the heavy .50-caliber bullets into the enemy ranks.

As Sparks watched, a burst from a submachine gun struck the man down; spurts of dust flew from the man’s jacket as the bullets went through him. “He was killed, but he stopped the Germans right at the edge of my foxhole.” Sparks didn’t even know the soldier’s name.

At midday, as the fight raged on, Sparks sent away his sole remaining tank destroyer, its ammunition depleted. It left at full speed with the Germans firing at it the entire way; Sparks watched rounds impact just behind it as it moved.

Shortly afterward, another wave of Germans attacked, several battalions directing their strength at E Company. This time, Sparks saw only one way to stop the assault: he called in artillery on his own position, a tactic only used as a last resort to avoid being overrun and defeated. E Company’s troops were still in their foxholes, while the Germans advanced in the open. The attack was finally stopped, broken up by the deadly, explosive power of the artillery, but the fight was far from over.

E Company fought for its life that morning because it sat at the boundary between the 157th and 179th Infantry Regiments’ segments of the line. Such boundaries were vulnerable spots an attacker could exploit. On February 16, 1944, the Germans launched a major counterattack designed to pierce Allied lines and drive them back into the sea. That attack’s point of focus was Company E’s position.

The Anzio landings were less than a month old when this counterattack—dubbed Operation Fischfang by the Germans—occurred. The Allied Fifth and Eighth Armies had earlier hoped to outflank the well-emplaced Germans in the Gustav Line to the south, either forcing them to withdraw or pinning them between two Allied forces. In the event, the Anzio invasion failed; the Allied VI Corps commander, American Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, didn’t move his forces fast enough to get inland to the high ground where he could block Axis movements.

Even if he had, it was doubtful whether the landing force could have been reinforced and supplied sufficiently to prevent its destruction by German counterattacks. Whatever the case, several American and British divisions were ashore at Anzio, and they were as determined to hold their beachhead as the Germans were to push them out. The stage was set for a struggle of wills between the two sides, and the 157th Infantry Regiment sat in the center of the cauldron.

The 157th Infantry was part of the 45th Infantry Division, known as the “Thunderbirds” for the Native American Thunderbird design on their shoulder patch. This National Guard division drew units from Oklahoma, Colorado, and New Mexico, and contained large numbers of Native American troops.

Activated in 1940, by early 1944 the 45th had participated in the invasions of Sicily and Salerno, and then fought in the mountains at Venafro, near Cassino, before being pulled from the front line for transfer to Anzio in January 1944.

The 157th formed the division’s Colorado component. Commanded by Colonel John H. Church, the regiment was organized along standard U.S. infantry lines, with three battalions reinforced by a few organic units, such as an anti-tank and a cannon company. The regiment regularly received support from divisional artillery and attachments from tank, tank-destroyer and engineer units. The M10s supporting Sparks’ E Company on the morning of February 16 came from the 645th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

While the regiment was well-supported and supplied, it faced the combined might of several German divisions with their own tank, artillery, and air support. Since arriving at Anzio, the 157th had fought several small battles against Wehrmacht forces, but now it stood directly in the path of an onslaught designed to wipe out the Anzio beachhead completely.

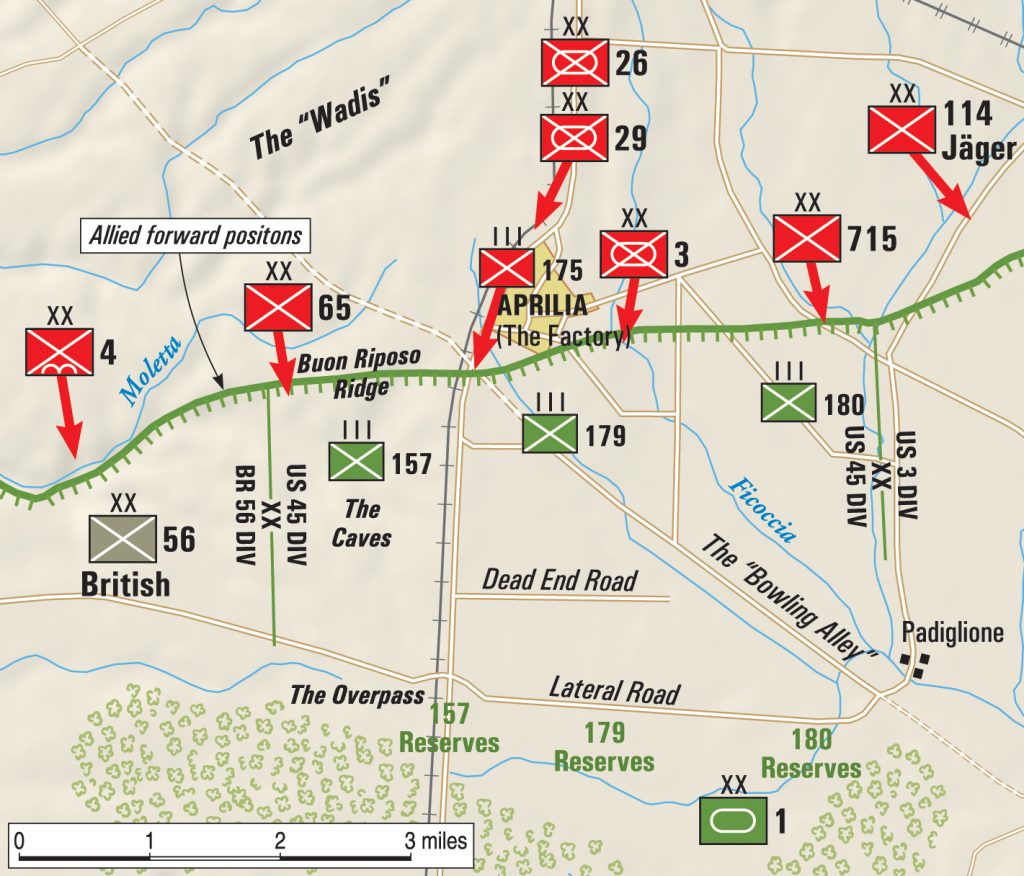

The Germans gathered three corps containing eight divisions and numerous supporting regiments and battalions for their counterattack. The main attack concentrated along the Via Anziate road, closely coinciding with the six-mile section of front defended by the 45th Division. The German 715th Infantry and 3rd Panzergrenadier Divisions spearheaded the attack, focusing on the 45th Division’s 157th and 179th Regiments, giving the Germans a 3-to-1 advantage at their point of attack.

Diversionary attacks took place on both flanks of the main attack, striking the British 56th and U.S. 3rd Infantry Divisions. German armor used the small village of Aprilia as a base; they would sortie from there and make their attacks before returning to replenish their ammunition and fuel. Aprilia was known to the Allies as “The Factory” because the church’s bell tower and a matching tower at city hall looked like industrial smokestacks.

As the attack pushed down the Via Anziate, it would reach a prominent feature known as the Overpass. This was in fact an actual highway overpass for an unfinished road that went over the Via Anziate and the railroad tracks that paralleled it. The Overpass had no real tactical value other than as an easily recognizable landmark on the mostly flat terrain. If the Germans could punch through along this axis and reach the coast a few miles beyond, they would cut Allied forces in half and could defeat each part in detail.

The German counterattack began at dawn on February 16, 1944—a cold morning with a misty fog lying across the battlefield. The usual harassing fire from artillery and mortars had punctuated the night and then suddenly stopped, leaving a silence that seemed almost as deafening as the bark and crash of shells.

The quiet lasted only a few minutes—the German gunners were preparing for their new fire missions—before the GIs, huddled in their foxholes, heard it. In the distance, cannon fired, mortars launched their bombs into the air, and the dreaded Nebelwerfers fired their rockets, which shrieked through the sky with a terrifying noise.

A barrage was coming—the Americans crouched deep into their foxholes or dove into dugouts, pressing into the mud as the incoming fire rushed down on them. Explosions ripped the landscape, sending hot shards of jagged shrapnel in all directions. The blasts shook the ground; if a round landed directly in a foxhole, the occupants were almost certainly killed.

The German artillery pounded the Americans all along the line and behind, aiming for headquarters and assembly areas. While E Company got a shelling of about 10 minutes, in some places the bombardment went on for over an hour.

Lt. Col. Ralph Krieger, commanding the 1st Battalion, 157th Infantry (1/157), recalled the barrage: “It was hell, I’ll tell you for sure. I lost quite a few people, including my orderly. We were in an advanced CP [Command Post] in a ditch, and the Germans started shelling us. He got hit by a direct hit on his foxhole; I was right alongside him. How I missed getting hit, I don’t know. My S-2 [Intelligence Officer] was wounded at the same time.” Krieger’s battalion was behind the lines, however, and was spared the worst of it.

The 2nd Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Lawrence Brown, had moved into the front line the night before and was barely in position when the attack came. It was astride the Via Anziate, with G Company on the left on the Buon Riposo Ridge, in reality just a slightly elevated point in the otherwise-flat terrain. F Company was in the center, with E Company on the right. H Company, the battalion weapons company, sat in reserve.

This was when Captain Sparks’ E Company was hit head-on by the attack. The neighboring 179th Infantry also bore the brunt of German tanks and artillery, with its forward companies battered and in one case surrounded. They fought back, however, with observers directing heavy artillery fire at the attackers.

On the 157th’s left, the British 56th Division suffered a two-division assault from the German 4th Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) and 65th Infantry Divisions. The British section of the line contained wadis (dry creek beds) that the Germans used as a route of infiltration. During the confused fighting, the British pulled back, leaving the left flank of the 157th exposed. Meanwhile, the German attack on the 157th overran F and G companies, leaving E Company similarly exposed.

Sparks had one platoon on the west side of the Via Anziate, and it was practically wiped out. “The damn fool Germans finally discovered we had nobody on our flank,” Sparks stated. “I don’t know why they didn’t figure it out earlier, but they didn’t. The Germans would fight like hell but sometimes they were utterly stupid.”

The rest of the battalion also fought for its life. Pete Conde served in the 157th’s Anti-tank company, equipped with 57mm guns only marginally effective against the armor of German tanks and assault guns. “After the British withdrew, our flank was open,” he said. “The Germans came in and really surprised the mortars [mortar platoon] behind the hill, where I was. Many of our fellows were captured.”

The 3rd Battalion, 157th (3/157) sat in positions about two kilometers behind 2/157. The men in 3/157 saw the Germans overrun their GI brethren and continue attacking southward toward the coast. K Company’s Bud McMillan endured the barrage with his platoon and watched as the Germans started across the open ground right in front of them. Bud carried a sniper rifle and put his marksmanship to deadly use.

“I was able to shoot the ones I thought were officers or NCOs,” he recalled. “You pretty well had your choice of what you were going to shoot at. Up to 400 or 500 yards, you could really pick ‘em off.”

The Germans kept coming in rushes—advancing a short distance before dropping to the ground, rolling sideways so they wouldn’t rise again in the same spot, and then dashing ahead once more. Their own machine guns and mortars fired to cover them. McMillan continued, “I was in the slit trench, just shootin’ at them, and a piece of shrapnel came down and hit me in the right thigh.

“I took off my belt and tied a tourniquet around my leg and I kept on fightin’. There really wasn’t but about nine or 10 of us doin’ any shootin’—the rest were either gone or in hidin’. Just to our immediate front there must have been a hundred or more Germans running right at us.”

The early-morning darkness may have helped Don Amzibel, from L Company. On outpost duty when the attack began, he watched as flares lit the early-morning sky and panzers clanked toward him. He remembered, “German soldiers were running by us as if we weren’t there. Of course, it was dark, and maybe they were doped up.”

Amzibel and his fellow soldier in the outpost snuck back to the company’s main position, shouting the password to avoid being shot by the sentries. In danger of being surrounded, L Company fell back. It was the first time Don had been in a retreat.

When 1/157 moved into the fight they also ran into the German advance. Like Sparks, Captain Kenneth Stemmons, commanding B Company, had to call in artillery on his own foxholes. He said, “When the Germans finally broke through … with infantry and tanks and a little bit of mechanized stuff, it got so bad that I had to call for artillery on our position. I had asked for quite a bit of it and they replied, ‘Let us give you a little bit to see if that’s what you really want.’ But we were in our holes and the Germans were running around in the open. We got the artillery and the Germans suffered terrible casualties.”

Infantry firepower also came into play that morning. 1st Sgt. Daniel Ficco of C Company told his men to hold fire until a few hundred Germans crowded an open area in front of them. “Then I gave the order and we fired. We had some mortars, and the ground was almost black with Germans coming at us. I was firing an M-1 and it got so hot, I could hardly touch it; I don’t know how many rounds I put through it.”

Still, artillery played the decisive role on the 16th. The 45th’s artillery poured fire into the waves of German attackers. Mel Craven of A Battery, 158th Field Artillery Battalion, recalled being taught in basic training the maximum rate of fire for a 105mm howitzer was four rounds per minute. “When the attack came, I and another man were on a two-man gun watch; the rest of the crew was asleep. When the Germans hit, we didn’t have enough time to call and wake them.

“By the time the rest of the crew got out of their foxholes and down into the gun pit, we had almost expended 30 rounds of ammunition.” He estimated their rate at 10-12 rounds per minute. “After a captured German soldier came back through our lines, he had one request—he wanted to see our ‘automatic artillery.’ That gave us an indication what rate of fire we were putting out.”

Felix Sparks still fought for the life of his company. At midday, a German halftrack appeared with a white flag. A German officer got out and asked for a 30-minute truce to evacuate the wounded on both sides. Sparks agreed, loaded his own casualties in his last running truck, and sent them back. Afterward, the fighting resumed, and the young captain once again called in artillery on his own position, stopping the attack for the moment.

Nearby, G Company’s commander, 1st Lt. Joe Robertson, also became desperate. Two hundred dead Germans and several knocked-out tanks littered the ground in front of his men, but one platoon was lost, and the enemy was closing in. Robertson, too, called in the guns on his own position, but the Germans kept coming, leaping into the American foxholes and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. The Americans fell back as enemy tanks arrived, blasting the foxholes with direct cannon fire.

A few miles back, 3/157 took up positions around the Overpass and immediately came under intense artillery fire. They knew the German attack was aimed at reaching the beaches and cutting the Allied position in two. They had to hold. The incoming fire forced the battalion CP to move back 600 yards, and the aid station was hit several times. Despite everything, they held.

Nightfall brought only slight respite. 1st Sgt. Ficco took two Native American soldiers on a patrol to capture a prisoner. They snuck across a canal amidst a large number of German troops and found tanks and armored vehicles preparing for an attack. They continued on until they spotted a lone German sentry guarding a bridge over the canal. Ficco told his men to wait there while he snuck down the road to approach the sentry from the other side.

He walked straight down the road so the guard would challenge him. When that happened, the two GIs rushed out and took the sentry unawares. Ficco’s patrol made it back to friendly lines. They then called in artillery on the enemy armor preparing to attack. The Germans did attempt a night assault on G Company, using the wadis to its left, but the Americans perceived their enemy in the dark and set up machine guns and BARs on the ridge. Thousands of .30-caliber bullets rained down on the area, breaking up the attack and filling the wadis with dead Germans.

Bud McMillan remained at his post despite his wounds, firing his sniper rifle. He recalled that at dusk, a group of British soldiers appeared. They promptly fixed bayonets and, at the blast of a whistle, charged the Germans. McMillan decided it was time to go, fearing the activity would bring down mortar fire on the position. He got near the Overpass, where a British tank was firing into the darkness. Some British troops found him and filled his canteen cup with tea. Shortly after the tank was hit, a truck appeared, and McMillan was put in it next to a wounded British tanker. They were evacuated to a hospital near Anzio.

Felix Sparks used the darkness to get help for E Company. He was supposed to meet a platoon of five M4 Sherman tanks, but he got only two. He took them anyway and placed them where the tank destroyers had been earlier; they would prove useful the next day. That night a company of Germans from the 715th Division crept into E Company’s outpost line and killed or captured all the sentries. As the sun rose on February 17, there were now fewer than 50 men left in the company.

The new day brought a renewed effort from the Germans. They’d suffered heavier-than-expected casualties the day before—1,700 men—and expended more ammunition than planned. Success would have to come quickly, before the attack ran out of men and materiel. Despite their slow progress, the Germans did manage to force a gap between the 157th and 179th and became determined to exploit it.

That morning, Luftwaffe aircraft roared in, strafing and bombing to further soften the Americans. Before their arrival, the German artillery had used up a significant portion of their remaining ammunition. This bombardment forced the defenders to take cover while 14 German infantry battalions from various units moved into the assault.

American artillery replied, joined by two Navy cruisers, each of their six-inch shells equivalent to a 155mm howitzer round. U.S. troops often complained that the U.S. Army Air Force was rarely present over the battlefield; a common joke among the soldiers in the Anzio beachhead described the 36 hours a day of air cover they got—12 from their own air forces and 24 from the enemy’s.

This morning, for once, the Allied air power arrived ahead of the Luftwaffe. Hundreds of bombers appeared overhead, dropping 1,100 tons of bombs on the Germans—to that date, the highest tonnage of bombs dropped in a ground-support mission. As soon as the Allied planes left, however, 45 Stukas appeared, bombing and strafing as German ground troops tore at the gap between the 157th and 179th regiments, determined to make a hole through which they could pour to the coast.

Atop Buon Riposo Ridge, Corporal Henry Kaufman lay in his slit trench, enduring the bombardment. When it ended, he crept out, determined to find better cover. Dead Americans—sometimes only pieces of them—dotted the landscape. He found a friend, Pfc. Fred White, and they set off together.

Suddenly an enemy tank appeared; the two men took cover near a 10-foot-high cliff as the tank fired several rounds. Explosions crashed around them as they tried to dig in with their entrenching tools. After a few minutes, the tank left. Kaufman discovered that the small cliffside had collapsed, burying White. He quickly dug the man out, finding him miraculously unhurt.

The remnants of 2/157 grimly held despite the battering of artillery, tanks, and infantry. As it was pushed back, the battalion occupied an area known as the Caves, a series of tunnels carved into a hill. Built during World War I, likely to store gunpowder, the sandstone walls were hardened by years of exposure to air. A number of chambers made up the interior of each tunnel. At least 50 women and children, refugees from Aprilia, were sheltering in the Caves when the American arrived.

The battalion CP set up in one cave, and men from the companies straggled in as the day continued, though E and G Companies were virtually cut off by this time. German tanks roamed the field behind G Company, firing on any target they found. Two tanks even penetrated through the American lines, moving toward the Overpass. American gunners knocked out one tank just short of the feature, but the other tank drove right through it, only to be destroyed on the other side by focused gunfire.

Sparks’ E Company, also cut off, suffered heavily from relentless attacks by the 725th Grenadier Regiment. The M4 Sherman tanks he’d received the night before turned the tide, keeping the enemy at bay with cannon and machine-gun fire.

Sparks had only 28 men left now, and they were almost out of ammunition. Finally, orders came to fall back to the Caves. He waited until full daylight that morning, fearful of losing men in the dark, before moving his shattered company to a small hill near the Caves and overlooking the road. The artillery dropped smoke to cover their movement.

“We were the right flank of the battalion,” he recalled. “We had excellent observation and dug in a circle. The Germans went by us and left us alone. But what the damn fools didn’t know was that I had an artillery radio, and every time I saw a group, I brought in artillery fire on them.” The Sherman tanks moved back, but not before knocking out two panzers.

Now a portion of the battalion occupied the Caves, with the rest in fighting positions just outside, where they could continue the battle. Captain Peter Graffagnino, battalion surgeon, set up an aid station in the Caves; captured German medics and doctors helped tend the wounded from both sides. Pete Conde spent the day carrying water cans into the Caves; he recalled seeing one German doctor with a pistol still on his belt as he tended the injured. No one had thought to take it from him.

One E Company man, separated from his unit, found his way to the Caves just ahead of a hundred Germans. He warned the men inside of the impending attack. Rifle fire and grenades forced the enemy back, but another company-sized attack came at dusk, getting close enough for hand grenades to fly back and forth again.

G and H Companies fired on the enemy from their position on the ridgeline just above the Caves while, inside, Captain George Hubbert, the battalion’s artillery-liaison officer from the 158th Field Artillery, called in fire missions. U.S. artillery rained down for two hours until the surviving enemy fled.

The fighting continued all night. Henry Kaufman remembered the close combat: “We were trapped by the Germans and unable to move more than 15 or 20 feet outside of the cave…very close hand-to-hand combat, with fixed bayonets, right outside the entrance to our cave…We somehow managed to kill several Germans outside the cave; in the ensuing battle, we captured an entire German machine-gun nest consisting of three Germans and their machine gun.” The captured men and weapon were pulled into the cave.

This went on for the next several nights. Water and food ran out; men became desperate to quench their thirst. The 157th’s official history stated, “Near one company sector trickled a stream in which lay several dead Germans, who had been cut down by machine gun fire. The water ran blood red but the thirsty men filled their canteens, boiled it, and drank it.”

The Executive Officer of B Company, Philip Burke, stated, “We were hit by a German attack, but they couldn’t get us because the apertures and openings to the Caves were easily defended…The part of the Caves I was in had two or three openings from which we were defending. We couldn’t move out except at night, when we’d go down to the creek to get the dirtiest water I ever drank. It was drainage from the farms in the area.”

The Germans slowly continued to gain the upper hand, but they suffered, too. The Allied artillery proved relentless and never seemed to run out of ammunition; the air strikes also made their mark, and even battle-hardened German troops grudgingly admitted the Americans’ doggedness.

A letter written by a German soldier revealed the strain: “The 45th American Division have had us in an uncomfortable spot. These damned American dogs are bombing us more and more every day. For a few days, a damned American with a Browning automatic has been shooting at us. He has already killed five of our men. If we ever get hold of this pig we will tear him to pieces.”

Another soldier from the 715th Division wrote: “It’s really a wonder I am still alive. What I have seen is probably more than many saw in Russia. I’ve been lying day and night under artillery barrages like the world has never seen.”

Hans Schule, of the 7th Company, Lehr Regiment, recalled the relentless shelling and bombing during his unit’s attack. “The terrible fire had already completely demolished us before the attack and our morale was destroyed. With guns we were threatened by our officers and non-commissioned officers and forced to leave our shelters and go into the attack.

“The enemy artillery became even stronger and we could find shelter only in the shell holes…I found myself with an American in the same hole…We stared into each other’s eyes, neither of us reacting. I then understood that the American infantry were under the fire of their own artillery.”

Afterward Schule took the American prisoner and marched him back to his own lines, disregarding an order from an officer to kill the GI. The next day, Schule realized his regiment “did not exist anymore.” This was the Lehr Regiment’s first time in battle; even Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German commander in Italy, later acknowledged the unit should never have led such an assault. Pulled off the line, the remnants of the Lehr spent the next two days carrying dead Germans back to casualty-collection points.

With 2/157 cut off at the Caves, the rest of the regiment deployed to bolster the line and defend the Via Anziate route near the Overpass. Its embankment ran 100 yards to either side, making it easiest to simply stick to the road on the way to the sea. At the moment, only I Company protected it, formed in a semicircle in front of the concrete edifice. The division commander ordered K and L to join them; there could be no retreat from this position. Behind them, hasty defensive lines were filled with cooks, clerks, and mechanics from the 45th’s rear echelons.

1st Sgt. William Pullum of K Company remembered going to the Overpass: “We were on one side of the road and I Company was on the other. We were in front of the Overpass and were in a very tenuous position. We had an awful lot of folks wounded there. We were actually supposed to attack and relieve the men at the Caves, then realized we couldn’t. Daylight caught us and we started to get casualties like it was going out of style.” The intense enemy fire soon killed or wounded all the officers in K Company, so Pullum took command.

A large German unit charged I Company’s lines, only to be trapped in the curling loops of concertina wire the Americans had strung in front of their positions. GI machine guns chattered, cutting down the Germans as they struggled to get free. On the night of the 17th, the Germans tried infiltrating, using tank and artillery fire as cover, but I Company held on, receiving a resupply of ammunition but no food or water.

A few tanks from the 191st Tank Battalion reinforced the infantry, using the firepower of their cannon and machine guns to keep the Germans at bay. Sergeant Phil Miller drove one of the M4s at the Overpass: “It looked like the whole German army had risen up out of the ground and came charging at us. We hit them with everything we had and still they kept coming. I lost another tank from a direct hit from a German 88. My assistant gunner and I were the only two that got out; the three men in the turret were killed in the blast and fire.”

As badly as the attack smashed the American lines, the Germans suffered as well. War Correspondent Reynolds Packard watched the battle through binoculars. He later wrote he saw “tank battle and infantry fighting all along the skyline. German wounded and dead are so numerous as to actually hamper their attacks as advancing waves of Nazi infantry walk over a gruesome carpet of their own dead and dying.”

Later that night K and L Companies joined other British and American troops in a counterattack, aimed at reaching the Caves and restoring the front lines. The confused night operation went badly. At first, the Americans advanced 1,000 yards through artillery fire with lightning flashing overhead.

Jack McMillion of L Company recalled arriving at the end of the advance and hearing friendly fire on both sides of his unit. “This was supposed to be a small gap, but it must have been a half mile wide and there were just a few of us.”

A patrol went out but never returned. As the men waited in the dark, the officers deciding their next step, a panzer appeared with a long line of German troops advancing behind it. A Nebelwerfer crew also set up nearby.

GIs took cover in a drainage ditch as their enemy marched past, and McMillion watched the screaming rockets fly directly overhead toward the Overpass. The officers decided to fall back using the ditch, which angled away from the German column. They reached the Overpass just at dawn.

As they passed a farmhouse, some men in overcoats called out in English, “What outfit is this?” Somebody answered, and the men opened fire. They were Germans! Bullets struck the side of the house as the Americans dashed by. Luck was with them; all of them made it to the Overpass, with just one man wounded by a bullet to the buttocks.

The German plan for the 18th was for more of the same; five full regiments attacked with tank support and artillery—at least while the ammunition lasted. Just before noon, Captain William McKay, flying a Piper Cub artillery-spotting plane, saw at least 2,500 Germans advancing with tanks. He quickly called in the fire missions, and 224 Allied guns joined the bombardment, hurling thousands of shells at the attackers. Despite the devastation, the Germans kept advancing, determined to reach the Overpass and beyond.

Awaiting them, Companies I, L, and M endured the shelling. It was a rainy day, but GIs later recalled that the artillery was so intense that a wet haystack nearby was set alight. Jack McMillion recalled a stiff firefight: “Behind us, we had tank destroyers that had their noses over the embankment and were firing at the Germans, and the Germans were firing at them, and we infantry were hugging the mud in between.”

L Company’s mortar section went forward, trying to get within range of the Germans attacking the Caves; none of them returned.

Don Amzibel was in McMillion’s platoon. “We were spotted by the Germans,” he recalled. “I guess we interrupted their breakfast, because they started hollering at us and chasing us, waving their mess kits. Our top sergeant, Jack McMillion, fired a few shots…they retreated back to their line…The shelling was awful. Tanks fired a few feet over our heads, trying to knock the Overpass out of commission. Every time a mortar shell landed near us, we were buried with dirt and mud. If the Germans had broken through, they’d have cut the beachhead in two.”

A few men in I Company paid the Germans back. Jackson “Cowboy” Wisecarver used his light machine gun to kill 30 of the enemy in one day. Medic Joe Franklin recalled Wisecarver was also a deadly shot with a .45 pistol. “I couldn’t hit a wall with a .45,” Franklin stated.

The medic also remembered Kenneth Kindig, who carried a brand-new sniper rifle at the Overpass. As Germans tried to get through the wire in front of the company, he shot them down. “I was on the outskirts with that sniper rifle and they were coming up through some drainage ditches at us,” Kindig said. “I picked them off before they could get around to us.”

Some 25 enemy soldiers fell to Kindig’s fire, but he soon ran into bad luck. During a lull in the fighting, he had paused to eat some cheese and crackers when a mortar round exploded nearby. “A piece of shrapnel went through the front of my helmet and lodged in the back, between the helmet and helmet liner. I guess it knocked me out for a little bit. When I woke up, I was still sitting up and my can of cheese was running over with blood. The shell also blew the stock and telescopic sight off my brand-new sniper rifle.”

Kindig was evacuated after dark, the only time casualties could be moved without drawing fire. He spent a month in the hospital and later received a Bronze Star for his actions.

3/157 stayed in that precarious position, 100-150 yards in front of the Overpass, for three days and nights, fighting off repeated attacks. While 2/157 remained encircled at the Caves, Maj. Gen. William Eagles, the 45th’s commander, attached part of 1/157 to the neighboring 179th Regiment, which was also in bad shape after days of non-stop fighting.

The move allowed the 179th to shorten its lines while the 157th received American armored infantry from the 1st Armored Division as well as British troops to shore up the holes in its own lines. Further German attacks were repulsed with help of the division artillery, which fired 12,557 rounds on February 18 alone.

The fighting went on, but the tide had turned. The German offensive gradually ran out of energy; too many men lay dead and wounded, and there wasn’t enough artillery ammunition to match the Allies’ superior logistical ability.

February 19 and 20 were marked by German barrages and attacks all along the salient, but responding Allied artillery proved too heavy and accurate. All of this made little difference to the infantrymen of the 157th, still in their foxholes and CPs, enduring the enemy’s last attempts to break through. The battle transitioned to a test of willpower between two armies unwilling to concede.

The Germans deployed fresh troops to finish 2/157 in the Caves. H Company’s commander, Kenneth Kerfoot, recalled a harrowing enemy attack on the night of February 19: “We tried to get out that night…We had 70 or 80 men left out of a hundred, but 40 or 50 were walking wounded. German machine guns pinned us down. We would have been slaughtered, so we surrendered at the crack of dawn.”

As the enemy marched their new prisoners to the rear, Kerfoot saw immense stacks of dead Germans, awaiting burial, in piles chest-high going the length of a city block.

In the Caves on the 20th, Henry Kaufman watched as a German armored vehicle rolled up to the entrance of his cave. It carried a flamethrower and loosed a stream of fire into the cave, burning Kaufman’s right arm. The GIs threw hand grenades and fired armor-piercing bullets, driving the vehicle away.

Two days later, the Germans attacked again, this time using tear gas. Coughing, eyes burning, six H Company men, including Kaufman, surrendered. The machine-gun crew the GIs captured days earlier was liberated. When the Italian women came out, several Germans called them collaborators and started shooting them, until an officer appeared and ordered them to stop.

Kaufman saw 25-30 German bodies outside the cave’s entrance. One German ordered Kaufman and another GI to carry one of the dead to a collection point nearby. The German who gave the order said the dead man was his brother.

Felix Sparks and his last 16 men still sat in their isolated position on February 21. He received word that the battalion would be relieved by a British battalion, at which point the Americans would consolidate and withdraw after the British troops took over their positions. The British attempt met with heavy resistance; they reached Sparks’ position but had lost 76 men and most of their ammunition and heavy weapons along the way.

“He didn’t even have a machine gun, so I gave him ours,” Sparks said of the officer who commanded the group. The Americans fell back to the Caves and spent the night there. The Germans attacked again, and artillery was brought down, almost to the cave entrances. It stopped them that night, but on the 22nd a group of Germans got into one cave, captured a platoon of GIs, and freed a large number of prisoners.

An American lieutenant volunteered to go out and zero in the artillery. Armed only with a trench knife, he found a foxhole atop the Caves and called in fire missions for over an hour; he made it back inside afterward. Minutes later, orders came to evacuate the Caves—it was time to go. A man went to wake up the heroic lieutenant, who sat with a cigarette perched between his lips. The young officer was dead.

Lt. Col. Brown issued a timetable, hoping to keep the withdrawal orderly and prevent further losses. First spot went to G Company, followed by F Company, Battalion Headquarters, H Company, E Company, and finally the walking wounded.

At 1:30 AM, the first troops went out in single file. Sparks went back to his old position to retrieve the loaned machine gun, but the gun—and all the British—were gone. He went back to the withdrawing column and took the lead, guiding the survivors to a small bridge over a ravine; Sparks stood by until all of them were over it. After the last man crossed, Sparks stumbled over a dropped tin of British ration biscuits and ate them quickly before moving to catch up with the column.

Suddenly, a German machine gun opened up, long bursts flashing out into the night, seeking Americans to kill. “The Germans had established a line and we had wandered into it,” Sparks recalled. “The firing didn’t break out until about half our column had passed through their outpost.

“The bullets were really flying, and I was yelling, ‘Fire back, fire back!’ Then I yelled, ‘Everybody follow me!” Sparks ran to a nearby canal and fell eight feet to the bottom. He took a head count; only a dozen men had followed him. He decided to move out with the small band he had, warning them not to fire even if the Germans fired at them. Concealment in the dark was their best hope.

As they infiltrated, German voices called out to them, trying to determine who they were. The enemy troops threw a few grenades but did nothing more. They went on for another half mile and came across a British artillery position. Sparks shouted, “We’re Americans!” at the surprised British gunners, hoping they wouldn’t shoot.

The front half of the column got back to American lines; the rest were killed or captured, along with the unmovable wounded back at the Caves. Captain Graffagnino, the surgeon, had insisted on staying with them and also became a prisoner.

Lieutenant Philip Burke shot his way to freedom. As he moved through the ravines, he recalled, “The Germans were up above, firing down on us. I happened to have a submachine gun with me and managed to take care of a couple of them up on the high walls.” Though wounded, he made it back and was evacuated to a hospital, rejoining the battalion a month later.

Operation Fischfang ended in defeat for the Germans. While the casualties they suffered fighting the 157th in particular are unknowable, their total recorded losses for the operation were 5,389, including 609 captured. Some of the German units suffered so badly they never completed their casualty reports, so the actual number is higher, but also unknowable.

The 157th, however, paid a high cost for its part in stopping the German counterattack of February 16–20. Total casualties for the 45th Division during that period totaled 3,400, with another 2,500 evacuated for medical causes such as trench foot and exposure in the frigid weather.

Among the hardest hit was 2/157. When the Battle of the Caves began, the unit had 751 men; after the smoke cleared, it had 177. Some newspapers in America even referred to them as the “Lost Battalion of World War II.” Felix Sparks received 150 replacements when he got back to the beach, along with orders to reconstitute E Company; he was the only man left from his original company.

A few days later, another man, Sergeant Leon Siehr, made it back to American lines after evading the Germans; Siehr would die in action three months later. Air attacks continued to cause casualties in Sparks’ new company for days.

Despite all this death and suffering, the 157th held throughout the German attack. The regiment did its duty, though at a terrible price, and had to be rebuilt before it could return to the front lines. The focus of a four-day, six-division attack came right at it, even went through it and over it; but while the 157th bent, was bloodied and battered, it never broke.

The regiment continued to fight, landing in southern France in August 1944 (Operation Anvil), liberating the Dachau concentration camp, and ending the war in Munich on May 8, 1945. In all, it spent 511 days in combat with the 45th Division, more than any other recorded by an American combat unit. The seven days from February 16-22 ranked among the worst of them.