By Mark Simmons

“The big day came and we moved off to our positions. Shortly a huge bombing raid commenced on the town of Wesel, followed by an artillery barrage which virtually shook the very ground under us. It was very difficult not to be anything other than nervous and almost shell-shocked as we were virtually sitting under the bombardment.”

So recalls Fred Harris, a Royal Marine of 45 Commando, about the night crossing of the Rhine River at Wesel in March 1945—the Western Allies’ first major offensive in 1945. Fred continues in a lighter note, “I remember, of all things, mail coming up, which for me was in the shape of a food parcel, a homemade cake…. This was duly cut into umpteen pieces and passed around. Our turn came, we clambered into the Buffaloes [an amphibious tracked vehicle] and we were on our way down the bank and into the river. Since nothing could be seen from these vehicles, only the night sky and tracers overhead, there was little to do except try not to think about being sunk.”

Landing safely, Fred and his section moved rapidly into the town, taking up position in a factory that had been used to manufacture lavatory pans which lay shattered all around the building. They found the town a pitiful sight.

“It was one mass of craters and bombed buildings. God knows how anybody survived it, and how many troops and civilians were killed. American para-glider troops were also wandering around, no doubt dropped outside their zones. It was not unusual to hear ‘Hey Mac, have you seen our outfit?’ [These were troops from the U.S. 17th Airborne Division.]

“We were into Germany proper now, prisoners were more frequent and in fairly large numbers. It was noticeable how very young or very old the majority of them were….”

That March morning, B Troop of 46 Royal Marine Commando were the first British troops to set foot in Nazi Germany. Three months earlier, in January 1945, 1st Commando Brigade, including 45 and 46 Royal Marine Commandos and No. 3 and No. 6 Army Commandos, were in the U.K. having completed a period of training on the Sussex Downs and coast. One Marine then recalled, “If a morning exercise went well, the afternoon was free. If it went badly, we repeated it until we got it right, however long it took.” The brigade had been withdrawn from France after 83 days of continuous active service, starting with D-Day.

Two Commando brigades had taken part in the D-Day operations and had made quite a reputation for themselves: 1st Commando Brigade under Brigadier Lord Lovat, which was made up of Numbers 3, 4, and 6 Army Commandos and 45 Royal Marine Commando; and 4th Commando Brigade under Brigadier B.W. “Jumbo” Leicester, consisting of 41, 46, 47, and 48 Royal Marine Commandos.

“Steamroller Farm Engagement”

On June 6, 1944, Lovat’s 1st Commando Brigade, landing on the left of the British Second Army, was to clear the town of Ouistreham at the mouth of the Orne, then push inland to link up with elements of the 6th Airborne Division at Pegasus Bridge and secure the left flank of the invasion.

The 4th Brigade landed farther west in the area of Lion-Sur-Mer, seizing a number of coastal villages. No. 47 Commando operated far from the rest at the junction of the British and American armies where it would capture the harbor of Port-en-Bessin, during which it suffered severe casualties. No. 48 Commando lost half its strength within 24 hours but had captured the formidable strongpoint of Langrune.

On June 12, Lord Lovat was wounded and Derek Mills-Roberts was promoted to command 1st Commando Brigade. A former Irish Guards officer, Mills-Roberts had been with the Commandos since their formation in 1940, and had commanded a company in No. 4 Commando during the ill-fated Dieppe Raid in 1942. As a lieutenant colonel, he commanded No. 6 Commando in North Africa, helping to wrest the initiative from German forces after their victory at Kasserine Pass in Tunisia.

Mauling two German battalions at what became known as the “Steamroller Farm Engagement,” for which he was awarded the DSO, Mills-Roberts received a warm letter of thanks from General Dwight D. Eisenhower. He still commanded No. 6 Commando on D-Day, fighting from the beaches through to the paratroopers holding Pegasus Bridge. He would retain command of 1st Commando Brigade until the end of the war in Europe.

In September 1944, the 1st Brigade returned to England while the 4th Brigade advanced eastward along the French coast. In October, 46 Commando, which had been much reduced in numbers during heavy fighting against the panzer grenadiers of the 12th SS Division in the villages of Le Hamel and Rats, returned to England and changed places with No. 4 Commando.

River-Crossing in Holland

After replacements had been absorbed, 1st Commando Brigade had expected to be shipped to the Far East. But the German Ardennes offensive in December changed all that and the Commandos were sent to Holland instead, their task to help defend Antwerp. However, by the time they arrived on the ground, the last great German attack had already run its course and failed. The Commandos’ new role would now embrace spearheading the crossings of several rivers, including the Rhine, for the final drive into Germany.

On January 22, 1945, the brigade came under command of the 7th Armoured Division, which was in the process of conducting a probing action east of the River Maas in Holland, with the objective of driving the enemy back behind the River Roer and clearing the enemy forces between the two rivers.

At this time, the Germans were withdrawing to concentrate on the defense of the Fatherland, and it was not until the night of January 22/23 that No. 6 Commando crossed the Juliana Canal and occupied Maasbracht and 45 Commando took the village of St. Joostburg that contact with the enemy was made.

It was a bright, clear morning and bitterly cold, the landscape snow covered. By 10 am, 45 Commando had taken the lead moving through and searching Brachterbeek, where the men were greeted by some jubilant Dutch civilians. A Troop then moved onto the next objective, St. Joostburg, passing through another small village and on toward the Montiforterbeek Dyke containing a frozen canal.

H.E. Harden’s Victoria Cross

It was in this area that A Troop, the most advanced detachment, became heavily engaged in an exposed position and was unable to pull back until supported by other parts of the Commando. Here Lance-Corporal H.E. Harden would earn a posthumous Victoria Cross. Troop Sergeant Major H. Bennet spoke with Harden shortly before he was killed and he told him that the “casualties must be got in from the extreme cold to have a chance to survive.” Harden was, said Bennet, “cool and calm in dealing with his patients, even though he had been hit on one of his journeys.”

Part of Harden’s Victoria Cross citation reads:

“….on 23 January 1945, the leading section of a Royal Marine Commando Troop was pinned to the ground by intense enemy machine-gun fire from well-concealed positions. As it was impossible to engage the enemy from the open owing to the lack of cover, the section was ordered to make for some nearby houses. This was accomplished, but one officer and three other ranks casualties were left lying in the open.

“The whole Troop position was under continuous heavy and accurate shell and mortar fire. L/Cpl Harden, the RAMC [Royal Army Medical Corps] orderly attached to the Troop, at once went forward a distance of 120 yards, into the open under a hail of enemy machine gun and rifle fire directed from four positions, all within three hundred yards, and with the greatest coolness and bravery remained in the open while he attended to the four casualties. After dressing the wounds of three of them, he carried one of them back to cover. L/Cpl Harden was then ordered not to go forward again and an attempt was made to bring in the other casualties with the aid of tanks, but this proved unsuccessful owing to the heavy and accurate fire of enemy anti-tank guns. A further attempt was then made to recover the casualties under a smoke screen, but this only increased the enemy fire in the vicinity of the casualties.

“L/Cpl Harden then insisted on going forward again with a volunteer stretcher party, and succeeded in bringing back another badly wounded man.

“L/Cpl Harden went out a third time, again with a stretcher party, and after starting the return journey with the wounded officer, under very heavy enemy small arms and mortar fire, he was killed.

“Throughout this long period L/Cpl Harden displayed superb devotion to duty and personal courage of the very highest order, and there is no doubt that it had a most steadying effect upon the other troops in the area at a most critical time. His action was directly responsible for saving the lives of the wounded brought in. His complete contempt for all personal danger, and the magnificent example he set of cool courage and determination to continue with his work, whatever the odds, was an inspiration to his comrades, and will never be forgotten by those who saw it.”

It took most of 45 Commando, with the support of tanks and artillery, to gain a foothold on the Montiforterbeek Dyke. The next morning, No. 6 Commando cleared the dyke but found that all the bridges across the canal had been blown.

Raid on Belle Island

Meanwhile, No. 3 Commando had reached the outskirts of Linne, but spent an uncomfortable night huddled in small gullies on frozen, snow-covered ground. However, Royal Engineers had bridged the canal and some of the deeper gullies, and in the morning, with armored support from the 8th Hussars, the town soon fell.

On January 15, 45 Commando moved forward to Linne to assist No. 3 Commando and then farther forward to a position overlooking the River Maas. In the center of the river opposite B and E Troops lay a small, bell-shaped island that was given the nickname “Belle Isle” by the Marines (after the island of the same name off Brittany that was captured by Royal Marines from the French in 1761).

Later that morning orders were received to gain information on enemy forces on the far bank of the Maas in the Merum area. Thus the plan devolved on capturing the small island and raiding Merum.

On the night of January 27/28, unfortunately with a bright, full moon, D and E Troops crossed the Maas onto Belle Isle; once it was taken, B Troop was ordered to pass through them for the far bank. It was a difficult task in assault boats propelled by paddles against a current of six knots. Once ashore on Belle Isle, firing broke out. The element of surprise had been lost.

Captain J.E. Day of B Troop noted, “D Troop had a very bad time, clearly in serious trouble…. The B Troop raid was cancelled and I was told to reinforce the small bridgehead section and fix a line across the river so that a ferry service could be started.” It proved extremely demanding to extract D Troop from the island without heavy casualties, especially the wounded, some of which had to haul themselves with the aid of a fit comrade through the swirling, freezing waters. D Troop lost 11 killed, 13 wounded, and six missing.

Operation Plunder and Operation Widgeon

A thaw occurred during February and the tanks of the Hussars were soon bogged down. First Commando Brigade was pulled back to Venray and began training for the Rhine crossing, another task being to capture the city of Wesel.

For two weeks the men of 45 Commando stayed in billets with Dutch families in the Venray area, the luxuries of home living and cooking in complete contrast to the fighting they had recently experienced; many of the hosts and guests stayed in contact for years afterward. Groups of a dozen or so were fortunate to get 18 hours leave in Brussels. They left their unit in the front line dirty and tired and returned cleaner but even more tired.

Also, training got into full swing for the river crossings, the majority of which the planners rightly assumed would be fiercely opposed. Various types of craft were used––dories, storm boats, and the armored, swimming, troop-carrying Buffaloes.

Operation Plunder was the code name given to the British crossing of the Rhine, and Operation Widgeon was a subordinate operation by 1st Commando Brigade to capture and hold Wesel. The subordinate airborne and glider operation involving the 17th U.S. and 6th British Airborne Divisions was known as Operation Varsity.

On March 20, the 1st Commando Brigade left the Venray area and crossed into Germany. No. 46 Commando led, sending a patrol into the Well area and penetrating a few miles without opposition. The 1st Commando Brigade’s task as part of Operation Widgeon was to spearhead the crossing of the Rhine by Montgomery’s 21st Army Group between Rees and Wesel and drive on to capture Wesel after RAF Bomber Command had softened things up.

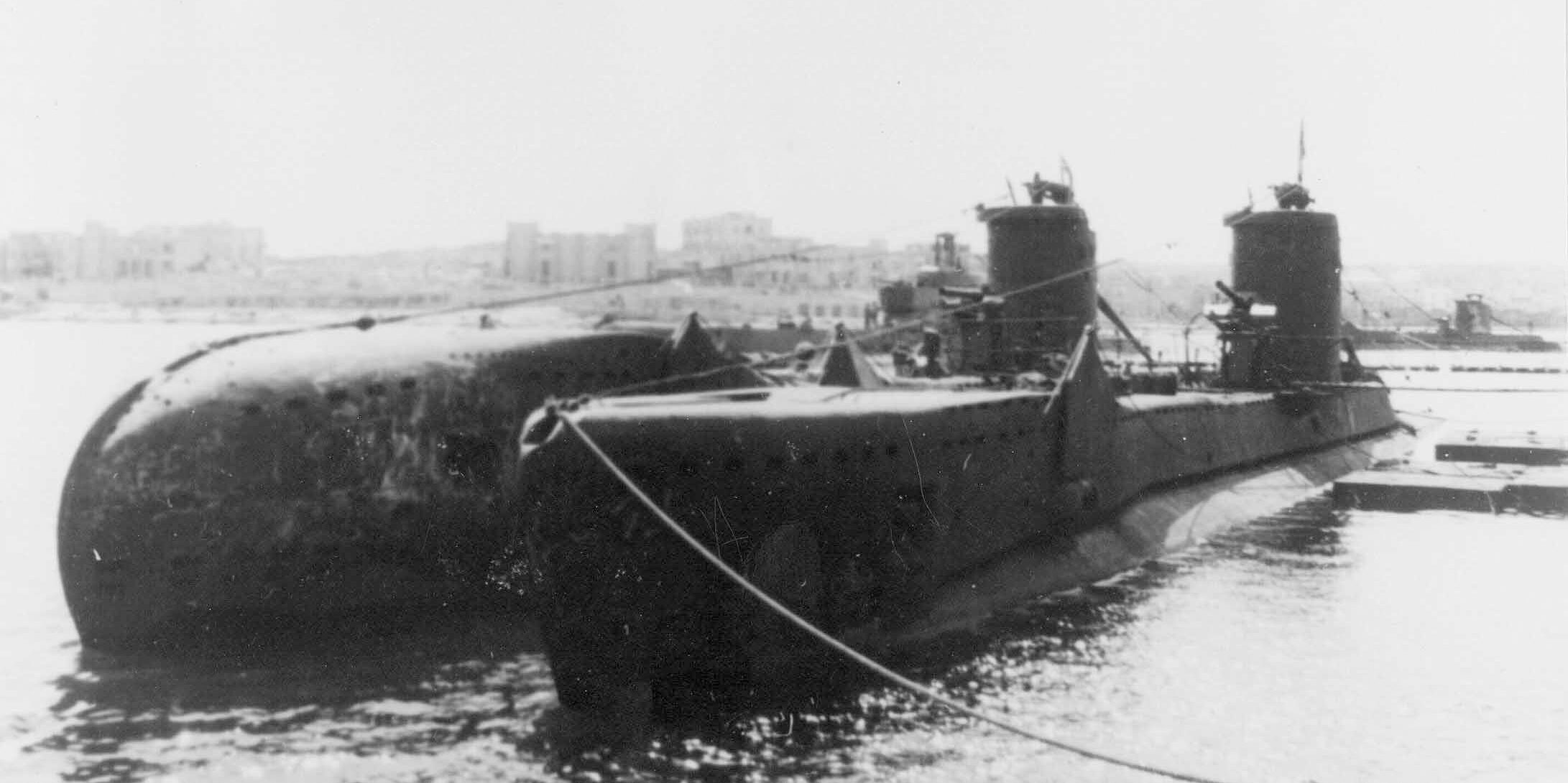

After heavy raids by Lancaster Bombers and an intense artillery bombardment, 46 Commando crossed the 300-yard-wide river in Buffaloes at 9:00 pm on March 23. One Buffalo was hit by friendly fire, but the bridgehead was secured. No. 6 Commando crossed in storm boats, coming under small-arms fire to which several men were lost.

Later, at 10:30 pm, 45 Commando crossed in Buffaloes. It was in one of these vehicles that Fred Harris sat, full of apprehension, in case a hit sank them. Captain Day of B Troop found that “the night was almost beyond description. To our right Wesel was being annihilated; to our front we could see the angry glow of the supporting barrage; to the left one Buffalo on the bank was ablaze; overhead we could hear the rushing wind of the long range shells, and at short intervals the bark of Bofors guns firing tracer to mark the flanks.”

Taking and Holding Wesel

Meanwhile, No. 6 Commando reached their forming-up position on Grav Insel, a flat area a mile west of Wesel, just as the Pathfinders of Bomber Command flew over the doomed city, dropping brilliant red flares, and the RAF began discharging over a thousand tons of bombs. Major C.E.J. Leophard led 6 Troop into the devastated city, which he said resembled “the surface of the Moon.”

The next day, hundreds of aircraft dropped the 6th and 17th Airborne Divisions on high ground west of Wesel. Shortly thereafter, a heavy German counterattack hit 45 Commando, which was holding a factory. The German infantry were beaten off but the tanks proved more difficult, causing several casualties in 45 Commando which had only light antitank weapons with which to defend themselves. However, artillery was soon again able to give fire support once all the paratroops were down, and a link-up with them was quickly made.

By the evening of March 25, the whole town of Wesel was in Allied hands and engineers had bridged the Rhine. The Commando Brigade had taken 850 prisoners and several hundred of the enemy had been killed, for the cost of 95 casualties to the brigade.

The Commando Brigade now took part in the advance to the Baltic. For this they had to cross the Weser, Aller, and Elbe Rivers. On April 3, now under command of 6th Airborne Division, they set out by road for their immediate objective: the ancient town of Osnabruck. It was attacked by night, the only serious fighting falling to 45 Commando. By 10:00 am the next day, the town had been taken, along with 450 prisoners.

Crossing the “Deep and Wide” Weser

The next river crossing was the Weser––“deep and wide.” The 1st Battalion of the Rifle Brigade had established a bridgehead in the town of Leese on the far bank, so 45 Commando was sent to reinforce them, crossing the river in nine assault boats. They were soon in a hot fight with the 12th SS Training Battalion, whose men, some merely boys, displayed fanatical courage even this late in the war. The Luftwaffe even made an appearance, attacking with a motley collection of about 30 aircraft and bombing the Engineers at the bridging site before attempting to fly along the river and strafe the Commandos and soldiers of the Rifle Brigade.

No. 45 Commando tried to break out from the bridgehead and capture the town of Leese. The fighting again was fierce, the Marines having to dig in to hold on. That night, April 6/7, they fell back to the bridgehead to cover the river crossing of the rest of the brigade. At 3:00 am, just as the crossing was taking place, the Germans launched another attack. B Troop bore the brunt of the attack on the right flank, but the young SS recruits made little headway and left the ground strewn with their dead.

By daylight, No. 3 Commando had crossed and the day passed fairly quietly. That night the advance was renewed and by 7:00 am the town had fallen, the enemy having abandoned it two hours before.

No. 3 Commando set out to capture a large factory in woods a mile or so to the north. In full view of the enemy, P.I. Bartholomew, the commanding officer just promoted to lieutenant colonel, leaped atop a tank and personally directed fire. When the factory fell to the Commandos, it was discovered that it was used to manufacture V-2 rockets. Inside, the Commandos captured a complete staff of scientists still in their white coats. Some of the 45-foot-long ballistic missiles were found fully armed on railway cars ready to be sent to the launching sites. The factory was well camouflaged from the air. (Some 3,000 V-2s, the world’s first ballistic missile built largely with slave labor, were launched against Allied targets mostly in London and later Antwerp, resulting in over 7,000 deaths of civilians and military personnel. The last V-2 attack took place in March 1945.)

Within two days of the fall of Leese, the Brigade was again called upon to lead the crossing of its third river in as many weeks. This time at the River Aller, on the night of April 10, they were to force a passage near the town of Essel for the 11th Armoured Division.

Brigadier Mills-Roberts decided to cross the Aller on the railway bridge a mile farther downstream rather than use the road bridge close to the town which the defenders would almost certainly blow. The whole brigade crossed the railway bridge, even though the first span had been blown, but this only ran across flat meadowland.

No. 3 Commando reached the road bridge and reported that it was held in strength. No. 6 Commando captured one end but the enemy sent in heavy counterattacks. The next day, 45 and 46 Commandos took the ground between the two bridges, thereby allowing engineers to build a Bailey bridge as the Commandos hung on; soon the tanks of 11th Armoured started crossing.

Passing Through Concentration Camps

The 1st Commando Brigade now acted as mobile flank guard for the advance of VIII Corps to the River Elbe. By April 19, they had covered 60 miles, passing the concentration camp at Belsen, to reach the old, picturesque town of Lüneburg, which had been largely unaffected by the war.

The Commandos here got a well-earned rest for a week, and passed the time with variety shows and games of soccer. On April 28, they moved off again to cross the Elbe, the last river crossing of the war for the brigade.

The Commandos were ordered to capture the town of Lauenberg and bridges over the Elbe, which was as wide as the Rhine with steep ground on the far bank. The crossing took place two miles downstream in Buffaloes. No. 6 Commando would seize the bridgehead while 46 and 45 Commandos would take the town.

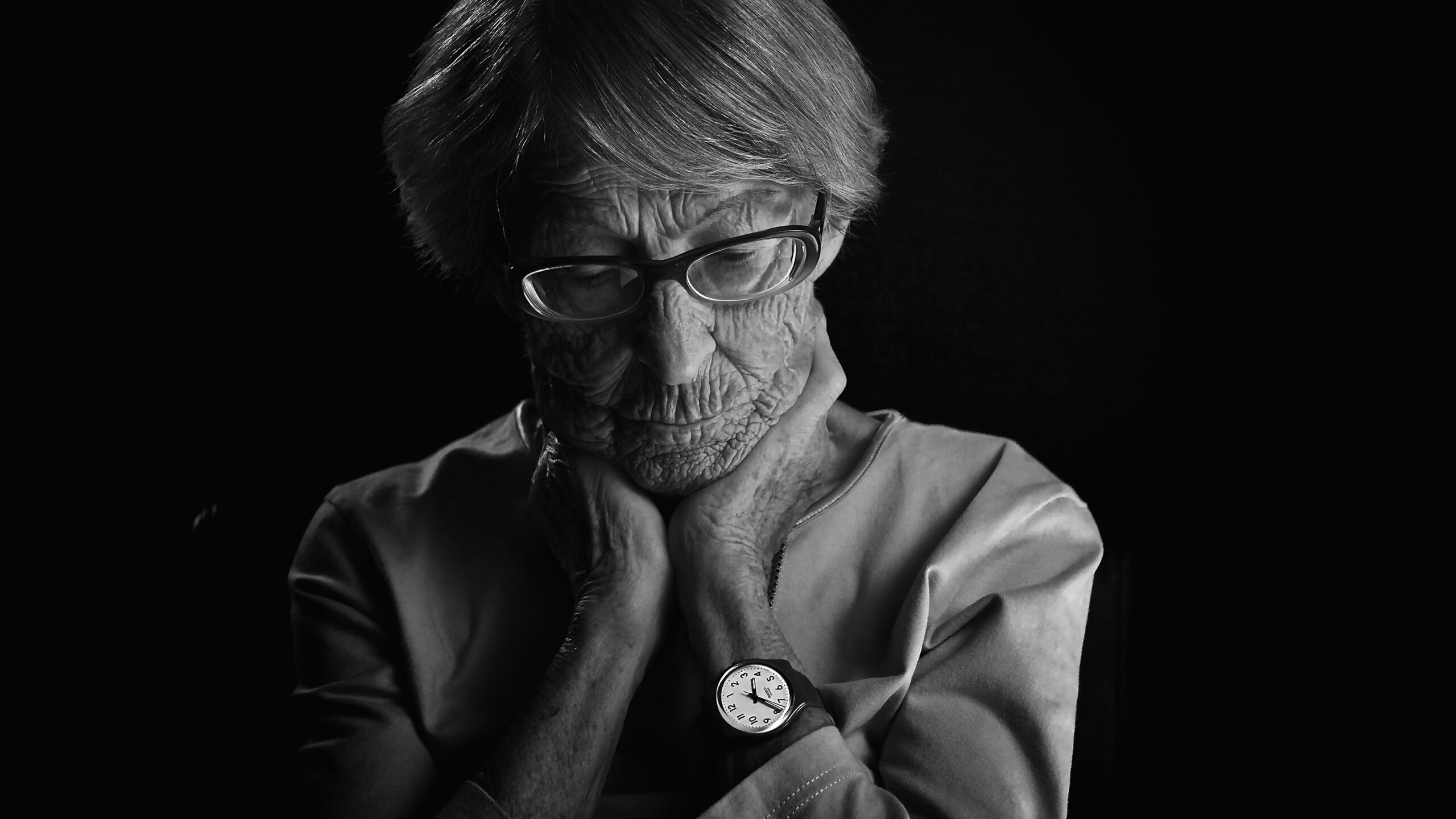

Fred Harris of 45 Commando, who had been with the unit since D-Day, remembers, “The end was in sight now. We moved to Lüneburg and had a short rest, then off towards the Elbe, which we crossed by Buffaloes. The many gun positions on the opposite bank were deserted, weapons and stick grenades being left intact.”

No. 6 Commando did come under some fire while crossing the river, but when 46 Commando and Brigade HQ crossed, resistance had been eliminated and B Troop of 46 Commando took more than 300 prisoners. Troop Sergeant-Major B.M Aylett caught one German soldier, blissfully unaware of what was happening, creeping across the courtyard of a house in order to wake the cook in time for breakfast.

A patrol of No. 6 Commando seized the main bridge over the Elbe-Trove Canal intact, taking prisoner a demolition party that was attempting to blow it up. Near here, Field Marshal Erhard Milch, Hermann Göring’s deputy, surrendered his baton to Brigadier Mills-Roberts who, it is said, disgusted with the sights the brigade had uncovered at Belsen and elsewhere, broke the silver-knobbed baton over the field marshal’s head, leaving him unconscious.

Bill Sadler, a corporal signaller with No. 6 Commando, takes up the story: “The brigade continued north unopposed to enter Lübeck and Neustadt, where they found the bodies of some 300 men, women, and children, all clad in pajama-type prison clothing, lying at the edge of the sea. All had been shot or drowned. The circumstances were never made clear. The brigadier ordered the burgomaster to provide a burial party from the most elderly citizens, and they were buried in one mass grave.

“Some years later I read an international paper that a mass grave had been discovered in the area. Apparently no one in the town had any knowledge of its existence or origin. A remarkable case of mass amnesia.”

“They Performed Whatsoever the King Commanded”

At the end of the war in Europe, 1st Commando Brigade stayed on in Germany for a while, helping to restore order during the early days of the Allied occupation. The brigade returned to Sussex in July 1945 and began to train for operations in the Far East; the Japanese surrender came before they were committed. In December 1945, 1st Commando Brigade was disbanded.

In London’s Westminster Abbey stands a small memorial, a statue of a Commando soldier, symbolizing all the Army and Royal Marine Commandos who fought in World War II, with a simple inscription on it: “They performed whatsoever the King commanded.”

These stories and accounts are well written and provide accurate information on allied support. To date most information we receive has been mostly of U.S. military.