By Cowan Brew

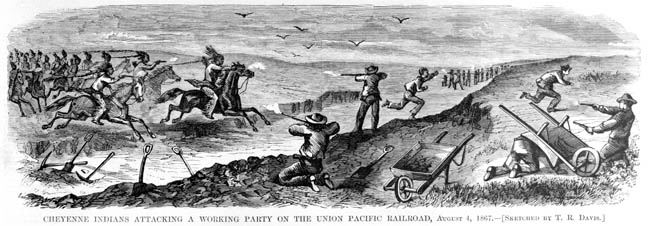

Under a bright, high sun in a pale blue Midwestern sky, six companies of the United States Cavalry’s 1st Regiment rode into a grassy valley bordering the south fork of the Solomon River in northwestern Kansas on the afternoon of July 29, 1857. Two miles away, unseen and unsensed, a party of 300 Cheyenne warriors waited silently on horseback amid a thin stand of cotton trees. They were planning to attack the unsuspecting Veho—white men—as soon as they got close enough to shoot. For the warlike Cheyenne, the hot summer day in the Moon-When-the-Buffalo-Are-Rutting was “a good day to die.” Most days were for the fearless Cheyenne, who were born and bred for battle. Few warriors lived to ripe old age—or wanted to. Death in battle was their greatest glory.

The Cheyenne were even more emboldened that day by the powerful magic that their two young medicine men, Ice and Dark, had worked on them that morning. Their old-fashioned Allen revolvers had been loaded with magical gunpowder that would make it impossible for them to miss, and to further add to their medicine they had dipped their hands into a sacred lake whose waters would cause the white men’s bullets to drop harmlessly at their feet. So confident were the Cheyenne of victory that they had even allowed a group of teenage boys to accompany them and witness the Vehos’ defeat. One of the boys, an Oglala Sioux called Curley, would never forget what he saw that day. In a few years, under the warrior name Crazy Horse, he too would fight the white men. But today, as a guest, he politely stood aside, silent and watchful, as his Cheyenne friends prepared for battle.

Another young man destined for fame and bearing, like Curley, the boyish nickname “Beauty,” galloped at the head of Company G, 1st U.S. Cavalry. His name was James Ewell Brown Stuart, a native-born Virginian and a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point (Class of 1854). Stuart and his comrades had been tracking the Cheyenne for 2½ months across four states in broiling sun and pelting rain. Now they had caught up with them, although the troopers didn’t pause to wonder why the normally elusive Indians had suddenly allowed themselves to be cornered. Instead, with the warriors shouting their war cries and the soldiers answering with a great shout of their own, the two sides drew ever closer. The booming voice of the regiment’s commander, Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner, rose above the others. “Draw sabers!” he shouted. “Charge!”

As Stuart and the others lowered their blades to tierce point, preparing to charge, the Cheyenne beheld a glittering steel forest slanting directly toward them. The Cheyenne, like other Plains Indians, feared no man in battle, but their medicine hadn’t prepared them to withstand the soldiers’ long knives. Perhaps it was a sign from Maheo, the Sacred One, that they were not intended to fight that day. With the oncoming soldiers less than 100 yards away, the warriors broke ranks and scattered unapologetically into the hills. They would live to fight another day.

Stuart and his comrades followed in close pursuit, chasing the Indians like so many random dogies, or loose cattle, while the warriors made a life-or-death dash across the river. When Stuart’s horse broke down, he hailed a private and commandeered his mount. Rank had its privileges. With a shout, Stuart raced after Captain James McIntosh and Lieutenants Lunsford Lomax, David Stanley, and James McIntyre, who had cornered a lone Cheyenne warrior armed with a decrepit Allen revolver. The warrior aimed his weapon at Lomax, and Stuart charged forward and shot the Indian in the thigh. The Cheyenne staggered from the blow.

Shouting, “Wait, I’ll fetch him!” Stanley dismounted and raced toward the warrior. Stanley’s pistol misfired, and the wounded Cheyenne limped toward him, clearly intending to go down fighting in a hand-to-hand struggle. Again Stuart charged, raising his saber and bringing it down on the warrior’s head. At the same time, the dying Indian got off one last round from a foot away. The ball crashed into Stuart’s chest; he reeled in the saddle while his comrades finished off their overmatched foe.

The other officers carefully laid Stuart on the ground and rigged up a cover of shade with their sabers and a horse blanket. They were sure he would die—no one could survive a pistol shot at such close range. But Stuart had more luck than the unfortunate Cheyenne that day. The pistol was old and ill kept, and the bullet had deflected off his breastbone and lodged painfully but not life threateningly behind Stuart’s left nipple. Beauty, too, would live to fight another day.

American history might have been very different had the unknown Cheyenne warrior used a better pistol that day. In a few short years, under a different nickname, “Jeb,” Stuart would become the Confederate Army’s most famous cavalry commander, serving under General Robert E. Lee in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War. He would do well, save for one glaring lapse before the Battle of Gettysburg, when his absence on an ill-advised foraging raid would leave Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia without adequate cavalry cover as it prepared to fight the largest and most crucial battle of the war. In a sense, the Union victory at Gettysburg was set in motion by Stuart’s unlikely survival on the banks of Solomon’s Fork, Kansas, almost exactly six years earlier.

Davis’s 1st and 2nd Cavalry Regiments

The brief and insignificant tussle at Solomon’s Fork was just one in a series of Army-Indian clashes involving the 1st Cavalry and its brother regiment, the 2nd Cavalry, in the half dozen years preceding the Civil War. And Jeb Stuart was just one of a remarkable number of future Union and Confederate generals who fought Indians together on the western plains before fighting each other in battlefields back east a few years later. Included on the regimental rosters were such future luminaries as Lee, Stuart, Albert Sidney Johnston, Joseph Johnston, George Thomas, John Bell Hood, Edmund Kirby Smith, Earl Van Dorn, William Hardee, and John Sedgwick. A stray arrow here or there might well have changed the entire course of the Civil War.

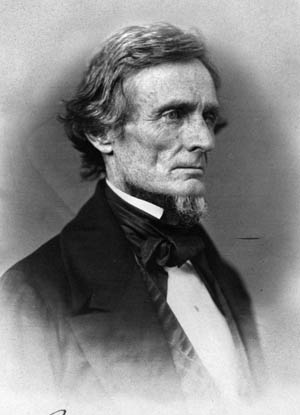

The illustrious 1st and 2nd Cavalry Regiments were the particular brainchild of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who lobbied President Franklin Pierce long and hard for their creation. Davis and Pierce had served with many of the regiments’ officers in the recent successful war with Mexico. But then-President James K. Polk, having won a singular victory in the Mexican War and increased the nation’s size by more than one million square miles, reduced the volunteer-swollen army’s temporary size to its congressionally mandated peacetime size of 13,821 men. In June 1853, five years after the Mexican War, the army had fewer than 7,000 men on active duty in the West—124 soldiers for each of the Army’s 54 western outposts.

In his first annual report to Congress in 1854, Davis complained bitterly about the reduced numbers. “We have a sea-board and foreign frontier of more than 10,000 miles, an Indian frontier, and routes through Indian country, requiring constant protection of more than 8,000 miles,” he noted, “and an Indian population of more than 400,000, of whom probably 40,000 warriors are inimical and only want the opportunity to become active enemies.” Davis petitioned for more soldiers.

Opponents in Congress, led by Union-leaning Senators Sam Houston of Texas and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, fought an increase in the military for a number of reasons, not least of which was their fear that such an army would be Southern-dominated, at a time when the winds of secession were just beginning to blow malignly across the country. They did not trust Davis, a Mississippian, to maintain a proper regional mix of appointments. Pierce, too, although a native of New Hampshire, was also suspected of pro-Southern views.

Opposition to Davis’s request crumbled in the wake of the shocking August 1854 massacre by Sioux warriors of 2nd Lt. John L. Grattan and 29 men under his command at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Grattan, a recent graduate of West Point, had impetuously led his men into a Sioux village to demand restitution for the tribe’s alleged butchering of a straw milk cow. The Sioux chief, Conquering Bear, asked Grattan to give him time to make restitution, but the hotheaded young officer, convinced that he could defeat the Indians with a single howitzer and a handful of men, refused. In the ensuing attack the howitzer misfired, and Grattan and his men fled in panic. The enraged Sioux followed and chopped them down. Although Grattan had been the obvious instigator of the fight, Davis characterized the fray as “a deliberately forced plan” by the Indians to raid government stores. He renewed his demand for additional troops to police the frontier.

Building the New Regiments

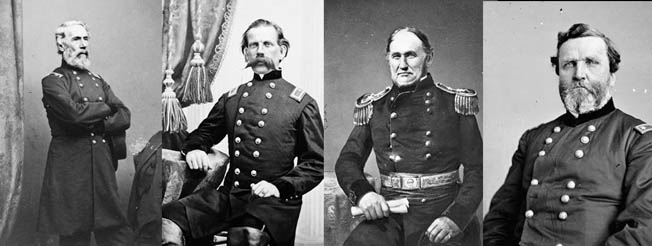

In the end, Davis got what he wanted. On March 3, 1855, Congress passed a bill mandating four new Army regiments, two infantry and two cavalry. Davis set to work immediately to fill the officer vacancies in the cavalry regiments, his particular pride and joy. Command of the 1st Cavalry went to Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner, better known to his men as “Old Bull of the Woods” for his thundering voice and hard head (an enemy bullet had literally bounced off his skull during the Mexican War, to no observable ill effect). Selected to lead the 2nd Cavalry was Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, a longtime Davis friend and a veteran Indian fighter in Florida and Texas. Understudying them were Lt. Cols. Joseph E. Johnston (1st Cavalry) and Robert E. Lee (2nd Cavalry).

Lee, then serving as superintendent at West Point, his alma mater, was not particularly thrilled by the new assignment, which would mean a forced separation from his beloved family and friends. But if Lee was not overly excited by his new post, most of the others were. Appointments to the new regiments were widely sought after by ambitious young officers. Captain Edmund Kirby Smith, who got a 2nd Cavalry posting, exulted in a letter home that he would be serving in “the regiment of the Army.” Stuart noted that “expectation is on tiptoe to see the correct list.” He received a 1st Cavalry post and gleefully boasted, “No regiment was ever marshaled into the field with such brilliant luminaries at its head.” He was more insightful than he knew.

Not everyone was thrilled. Critics in both Congress and the military took note of the apparently inordinate number of native Southerners appointed to the two crack regiments. Of the 25 officers chosen for the 2nd Cavalry, 17 of them were Southern born. After the Civil War, backward-looking critics would charge that Davis had deliberately stocked the regiments with fellow Southerners to give them valuable experience for the upcoming war. Future Union Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson, who also served in the 2nd Cavalry, disagreed, noting sensibly, “This was six years before the war, and a little too early for one to predict with any degree of certainty the supreme folly of a war between the sections.” Such criticism also failed to note that the commanding officer of the 1st Regiment was a Northerner, as were two majors, several captains, and a number of lieutenants in the two units.

After the officers were chosen, regimental recruiters began to fill the company rolls, tacking up posters in cities and towns across the country announcing the search for “able-bodied unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 45 for active service against Indians on the frontier.” Monthly pay was set at $22 for first sergeants, $17 for duty sergeants, $14 for corporals, and $12 for privates. Separate companies were recruited in Mobile, Baltimore, Memphis, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Evansville, Indiana, Logansport, Indiana, Rock Island, Illinois, and western Pennsylvania.

The “Jeff Davis” Hat

Recruits were not hard to come by, and eager applicants soon flocked to Jefferson Barracks outside St. Louis for training and equipping. The men were issued colorful new uniforms: dark blue jackets, pale blue trousers, silk sashes, yellow-braided trim, and black, broad-brimmed hats pinned up on the right with ostrich plumes trailing behind them. The new hat, immediately dubbed the “Jeff Davis,” replaced the leather-visored dragoon cap favored in the Mexican War. It proved less than popular with the men, who complained about its weight and fit. Groused one recruit, “If the whole earth had been ransacked, it is difficult to tell where a more ungainly piece of furniture could have been found.”

It would take more than smart new uniforms to fight the Plains warriors. Good weapons were particularly needed to offset the superior mobility and individual fighting skills of the Indians whom the soldiers were about to face. Eight companies of the 1st Cavalry and two of the 2nd were issued Sharps carbines; the others were given U.S. Model 1854 carbines. All carried Colt cap-and-ball six-shooters. A few companies were issued experimental arms—muzzle-loading Springfield pistol-carbines, Merrill breechloaders, and Prussian-style sabers. The plains would be the Army’s field laboratory for weapon testing.

To ensure the cavalry had the best possible mounts, the Army paid top dollar for Kentucky-bred horses. At $150 per horse, the price was well above the going market rate, but the War Department spared no expense to get its troopers into the saddle. Horses were divided by type and color among the various companies—grays, roans, sorrels, bays, and browns. The division was designed to encourage company pride and also make the units easily recognizable in the field.

“I Have Never Seen Men Suffer More.”

The 1st Regiment, headquartered at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, was the first to take the field, beginning frontier patrols in the late summer of 1855. With both Johnston and Lee called away to temporary court-martial duty, the 2nd Cavalry took longer to train. Major William Hardee, the author of a recent well-received book on infantry tactics, took over regimental drill instruction. A brief outbreak of cholera, coupled with blazingly hot weather and typical military slowness in getting supplies to the recruits, caused some of the more fainthearted to desert. Most, however, stuck it out, and morale soared after the popular Johnston finally arrived in camp.

Of the two new regiments, the 2nd undoubtedly had the harder task ahead of it. While the 1st was assigned to the rolling grasslands of Kansas, Nebraska, and eastern Colorado—ancestral home to 4,000 generally peaceable Cheyenne—the 2nd had to cover the vastly more inhospitable region of Kansas, Oklahoma, and northern Texas, home to 15,000 implacable Comanche warriors and their families. Universally considered the best horsemen on the plains, the Comanche ranged far and wide, continuing a generations-long tradition of raids into Texas and as far south as Mexico. They viewed the Southwest as their own private hunting ground, and anyone unlucky enough to wander into their reach was fair game. Raiding was their life, and they were enormously skilled at living it.

On October 27, 1855, the 2nd Cavalry finally broke camp and headed for its assigned duty postings in Texas. The 710-man column rode diagonally across Missouri, through northwest Arkansas and the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, making a mere 10 to 20 miles a day. Wives, children, slaves, and servants accompanying the caravan slowed it down. Constant rain and a year-long infestation of grasshoppers that had stripped the prairie of vegetation made travel across the forbidding landscape even more difficult. The weather soon turned cold, and early blizzards and sub-zero temperatures struck the columns. On some days the weather was so bad that the regiment had to remain in camp. Lonely graves dotted the frozen plains. “In the whole course of my military experience,” future Confederate general Kirby Smith would later write, “I have never seen men suffer more.”

“Rigorous Hostility”

At last, on December 15, the regiment crossed into Texas and marched to Fort Belknap above the Brazos River. Once there, the column split into two wings. Hardee took four companies up the Clear Fork of the Brazos to build an advance camp and watch over the nearby Comanche reservation. The rest proceeded to Fort Mason on the Llanos River, 170 miles away, completing the 750-mile trek on January 14, 1856.

As soon as weather permitted, Johnston sent the entire regiment into the field to conduct daily scouting patrols of the area. Texans had long pleaded for help from the federal government against the ferocious depredations of the flint-hard and ever-aggressive Comanche. The new regiment was intended to answer those pleas. Veteran plainsmen, however, scoffed at the untried troopers’ chances of controlling the Indians. “Keeping a bulldog to chase mosquitoes would be no greater nonsense than the stationing of six-pounders, bayonets, and dragoons for the pursuit of these red wolves,” scoffed one old-timer. Wolves, as everyone knew, were elusive.

Despite the old-timers’ doubts, Johnston’s policy of “rigorous hostility” to all nonreservation Indians soon paid dividends. “The troops ought to act offensively, to carry the war to the homes of the enemy,” he urged the War Department, noting that it was not enough to wait for the Comanche to strike and then try to run them down. Vigorous action, said Johnston, was needed to keep the Indians in check and on the defensive. He intended to do just that.

Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee, who had not made the march into Texas with the regiment, arrived a few weeks later and took command at Camp Cooper. He dutifully met with Chief Catumseh of the reservation Comanche but was less than impressed by the chief or his charges. “These people give a world of trouble to man and horse,” said Lee, using his favorite—if mild—pejorative, “and, poor creatures, they are not worth it.” Any attempts to humanize the Comanche, Lee warned, “will be uphill work, I fear. Force is the only corrective they understand.”

Heeding his own advice, Lee took the field in the summer of 1856 with four companies of the 2nd Cavalry. Fellow Southerner Earl Van Dorn of Mississippi served as his second in command on the expedition, and the celebrated scout Jim Shaw and his Delaware Indians rode along with the column as guides. The force headed west from Fort Chadbourne, scanning the horizon for telltale smoke signals. The soldiers found several abandoned campsites, but no live Indians. At the headwaters of the Brazos and Colorado Rivers, Lee divided his command into three groups to cover a greater area.

Van Dorn’s force, accompanied by Shaw, broke camp on June 29. That evening the soldiers finally spotted smoke signals. The next morning they swooped down on an unsuspecting Indian camp in a nearby ravine. Expecting to find large numbers of hostile Comanche sheltering there, they were quickly disappointed. Only three warriors and a woman were in camp, and one of the men quickly leaped onto his horse and escaped. The other two, gallantly defending the woman, were chopped down by the troopers’ gunfire.

The brief, one-sided skirmish at the ravine was the only action in Lee’s entire 40-day, 1,600-mile expedition. The cavalry averaged sighting one Indian every 10 days—hardly a worthwhile return on the Army’s investment of men, money, and time. Said a disgusted Kirby Smith, one of Lee’s party on the raid, “We traveled through the country, broke down our men, killed our horses and returned as ignorant of the whereabouts of Mr. Sanico [a Comanche chief] as when we started.”

Despite the lack of major battles, however, the incessant cavalry patrols put the always wary Comanche on guard, so much so that by the autumn of 1856 veteran Indian agent Robert S. Neighbors could write approvingly, “Our frontier has, for the last three months enjoyed a quiet never heretofore known. This state of things is mainly attributable to the energetic actions of the 2nd Cavalry, under the command of Colonel A.S. Johnston.”

Johnston’s popular reign as head of the 2nd Cavalry came to an abrupt end in May 1857 when he was ordered by his superiors in Washington to lead a punitive expedition—this time against white men, Mormon extremists who were attempting to secede from the Union. His replacement, Brig. Gen. David Emanuel Twiggs, continued Johnston’s aggressive policies. “Old Davey, the Bengal Tiger” was 67 years old, but he was still as active and disputatious as he had been as a young captain in the Black Hawk War several decades earlier. A tall, beet-faced man with a towering temper and an eye for the ladies, the Georgia-born Twiggs recommended keeping the pressure on the Comanche. “For the last ten years we have been on the defensive,” he wrote to his old Mexican War commander, General of the Army Winfield Scott. “It is time to follow them up winter and summer, thus giving the Indians something to do at home in taking care of their families, and they might possibly let Texas alone.” Scott gave him the go-ahead.

Hood’s “Most Gallant” Engagement

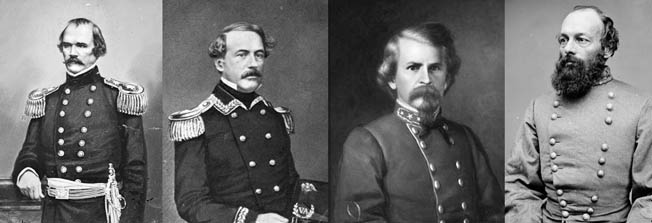

In July 1857, Lieutenant John Bell Hood rode out with 24 men from Fort Mason to scout the headwaters of the Concho River, a favorite Comanche haunt. Tracking the Indians for 12 days, he trailed them into the forbidding desert of the Staked Plains in the Texas Panhandle. After a 150-mile slog, the soldier came upon a fetid water hole on July 20, the only water they had seen in days. Fresh tracks alerted them to recent Comanche presence.

That afternoon Hood’s party crested a ridge and saw someone waving a white flag on a parallel ridge two miles away. Standing orders were to attack all Indians on sight, but since Hood had also received word that friendly Indians were moving through the area at this time, he decided to get a closer look. When he and his troopers got within 30 paces of the Indians, the waiting Comanche threw down the white flag, set fire to a pile of leaves to spook the soldiers’ horses, and began firing into their ranks while another 30 Indians swooped down on Hood’s flank. Comanche women followed the warriors, reloading their rifles for them and urging them on in combat with shrill ululations.

Hood, blasting away with a double-barreled shotgun, led the troopers forward. Desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The troopers swung their sabers at the Indians, who were attempting to bash in the heads of the soldiers’ horses to unseat their riders. One arrow struck Hood in the left hand, pinning it to the saddle. He would always have terrible luck in combat, suffering a crippled arm at the Battle of Gettysburg and losing a leg two months later at the Battle of Chickamauga. Jerking his hand free, Hood broke off the arrow and continued firing his shotgun. The soldiers were down to 11 unharmed men when the Comanche, at the mournful urging of their women, suddenly called off the attack, gathered their dead and wounded, and rode away. Hood estimated that the Indians had lost nine killed and 12 wounded. The fight, although strategically meaningless, brought Hood praise from Twiggs and Scott, who called the brief engagement “most gallant” and said it reflected much credit on the soldiers. It was the first mention of Hood’s later Civil War sobriquet, the Gallant Hood.

Braxton Bragg: “An Excellent and Gallant Soldier”

Following the death of his father-in-law in October 1857, Lee left the regiment for good. His successor, Major George H. Thomas, was a fellow Virginian who had been recommended for the post by his old Mexican War artillery commander, Braxton Bragg. Thomas, wrote Bragg, “is not brilliant, but he is a solid, sound man, an honest, high-toned gentleman, above all deception and guile. I know him to be an excellent and gallant soldier.” Ironically, Thomas’s famous stand at the Battle of Chickamauga six years later would deny Bragg the total victory that his luckless Army of Tennessee came within a hair’s breadth of winning.

Unfortunately for Thomas, the 2nd Cavalry commander, David Twiggs, nursed a longstanding grudge against him dating back to the Mexican War, when Thomas had refused to let Twiggs have a brace of mules for his personal use. They clashed again at a court-martial of a young lieutenant accused of stealing a drunken civilian’s purse. Thomas voted to absolve the officer of any wrongdoing, but Twiggs reversed the ruling. Thomas then went over his head to Secretary of War John B. Floyd, who upheld Thomas’s judgment and warned Twiggs not to interfere. Twiggs did not forget the slight.

“It Was a Bad Day For Vans”

Bad blood between the two surfaced again in September 1858 when Twiggs was preparing to lead a major expedition against the Comanche. Thomas, as ranking field officer in the regiment, expected to lead the offensive, but Twiggs placed Earl Van Dorn in charge instead, leaving an enraged Thomas back at Fort Mason to command a skeleton guard of noncoms, band members, and convalescents. Thomas saw it as the slight it was.

The dashing Van Dorn, with a newly won reputation as the best Indian fighter in the West, marched out of Fort Belknap in mid-September at the head of 225 soldiers and 135 Indian auxiliaries. On September 15 the force arrived at Otter Creek in southern Oklahoma, where they quickly threw up a log stockade named Fort Radziminski in honor of a popular young Polish lieutenant in the regiment who had died of tuberculosis the year before. Scouts soon spotted a number of Comanche teepees near a Kiowa Indian camp at Wichita. The Comanche, led by Chief Buffalo Hump, had come to present some stolen ponies to their Kiowa allies.

Riding all day and night, Van Dorn and his troopers reached the village before daybreak on October 1. Van Dorn divided his forces, sending one column around to the left to capture the Indians’ ponies while he personally led to the rest of the command forward after a shrill blast from the company bugler. The Comanche, literally caught napping, dashed from their teepees and ran for a ravine behind the village. In the predawn chaos, soldiers dashed through the camp, firing their carbines and swinging their sabers. One sergeant, John W. Spangler, personally claimed credit for killing six Comanche warriors singlehandedly.

The Indians fought a desperate rearguard action, seeking to cover their families’ retreat. Van Dorn, an accomplished horseman, raced after them, overtaking two fleeing Comanche who were riding double. The captain shot their horse, sending the Indians tumbling to the ground unhurt. Rising quickly, they let fly with bows and arrows. Reacting instinctively, Van Dorn threw up his hands; one arrow slashed into his wrist, the other struck him in the side, passing through his stomach and nicking his lung before coming out the other side.

Soldiers raced to rescue their badly wounded commander as Indian resistance quickly crumbled. Inside the ravaged camp, 56 Comanche warriors and two women lay dead; another 25 were mortally wounded. The soldiers lost four killed, including Lieutenant Cornelius Van Camp. “It was a bad day for Vans,” Van Dorn ruefully observed. A gratified Twiggs reported to Washington that Van Dorn’s raid on the Comanche village represented “a victory more decisive and complete than any recorded in the history of our Indian warfare.” It was a claim as grandiose as Twiggs’ shelving of Thomas was petty.

Van Dorn recovered quickly from his wounds, but his famous victory was soon overshadowed by a report that the same Comanche he had attacked had recently engaged in a parley with an Indian Affairs representative and mistakenly believed that they had reached a peace agreement with the white men. “One of us has made a serious blunder,” a chagrined Twiggs lamented, “he in making the treaty, or I in sending out a party after them.” The second guessing did nothing to help the dead Comanche or their furious chief, Buffalo Hump, who told Indian agents with some justification that henceforth his “heart was black” toward all American soldiers.

Van Dorn’s Second Victory

After five weeks recuperating at his Mississippi home, Van Dorn returned to the 2nd Cavalry at Camp Radziminski. The next spring he again took the field in search of the star-crossed Buffalo Hump and his band. The soldiers tracked the Indians to a camp on the Cimarron River in northwestern Oklahoma. Dismounting to attack in a misty rain, the troopers swept the Comanche toward a deep, steep-sided ravine. Kirby Smith, his glasses fogged by the rain, walked right past a concealed Comanche, who then shot him in the thigh. Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew, was also wounded in the fighting, taking an arrow through the chest before shooting his assailant between the eyes. Not a single Indian escaped—49 were killed, five wounded, and 37 taken prisoner. “The Comanches,” reported Van Dorn, “fought without giving or asking quarter until there was not one left to bend a bow.”

Van Dorn’s twin victories helped crush Comanche resistance in northern Texas, at least for a time. Meanwhile, the 1st Cavalry’s contemporaneous victory at Solomon’s Fork ended major Cheyenne hostilities in Kansas and Nebraska for several years. “Colonel Sumner has worked a wondrous change in their dispositions toward the whites,” remarked one Indian agent. “They said they had learned a lesson in their fight with Colonel Sumner, that it was useless to contend against the white man.” In the end, it was a lesson that would not last as intermittent hostilities between soldiers and Indians would continue for another two decades on the western plains, interrupted by much more urgent hostilities among the white men back east.

Cavalry Regiment Commanders, Civil War Generals

Two years after Van Dorn’s victory on the banks of the Cimarron, the elite fighting force put together by Jefferson Davis would find itself breaking apart in the wake of mass resignations by Southern officers heading home to fight for the Confederacy under now-President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee. The new war would pit officers of the 1st and 2nd Cavalry against one another on fields of battle from Pennsylvania to Missouri, and the frustrating, frequently inconclusive warfare they had conducted against hostile Cheyenne and Comanche warriors would be forgotten in the much larger war they fought against each other.

In all, 29 officers from the 1st and 2nd Cavalry would become generals in the Civil War. Robert E. Lee, of course, was the most prominent, leading the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia into military immortality. His commanding colonel on the frontier, Albert Sidney Johnston, would also become a full general in the Confederacy before dying early in the war at the Battle of Shiloh, his great promise largely unfulfilled.

Three other members of the two cavalry regiments would achieve the rank of full general in the Confederacy: Joseph E. Johnston, John Bell Hood, and Edmund Kirby Smith. Each man’s career would end in failure. Johnston was removed from command by Jefferson Davis after failing to prevent Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s relentless advance to Atlanta. Hood was similarly dismissed and reduced in rank to lieutenant general after dismally losing the Battles of Franklin and Nashville in the late fall of 1864. Smith had the distasteful task of surrendering the Confederacy’s last Trans-Mississippi army at Galveston, Texas, in June 1865. Serving as Confederate major generals during the war were William Hardee, Fitzhugh Lee, and Charles Field.

Along with Albert Sidney Johnston, Jeb Stuart and Earl Van Dorn also died in the Civil War. Stuart was killed by Union cavalry at the Battle of Yellow Tavern, Virginia, in the spring of 1864. One year earlier, Van Dorn, a notorious womanizer, was shot and killed in his tent by a jealous husband at Spring Hill, Tennessee, an inglorious end to his once promising career.

The Union’s Veteran Cavalrymen

Union Army veterans of the prewar western cavalry units also provided a mixed bag of victories and defeats. George McClellan, whose service with the frontier cavalry was mainly on paper (he resigned his commission in 1857 to go into the railroad business), later rose to command the Union Army of the Potomac against Robert E. Lee, winning the crucial Battle of Antietam in September 1862 before being sacked by an exasperated Abraham Lincoln shortly afterward for insufficient aggressiveness (and a too prominent Democratic Party affiliation). In 1864, McClellan ran for president against Lincoln and lost in a landslide, helped in large part by the failure of his former cavalry comrades Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood to prevent William T. Sherman from capturing Atlanta a few weeks before the election.

Edwin Vose Sumner, the rough-hewn commander of the 1st Cavalry, served as a corps commander under McClellan at Antietam, where he ironically was criticized for leading his division “like a colonel of cavalry” instead of remaining at the rear like other two-star major generals. Stung by the criticism, Sumner asked to be relieved of active duty. He died of pneumonia a few months later, drinking a final toast to the United States while he languished on his deathbed.

George H. Thomas, one of the few native Southerners from the western cavalry to remain in the Union Army during the Civil War, won fame as “the Rock of Chickamauga,” where his stubborn stand helped save the Union Army of the Cumberland from total destruction. Thomas later led the same army to a smashing victory over his old comrade-in-arms John Bell Hood at the Battle of Nashville. His unfortunate knack for alienating his superiors continued, and Thomas’s postwar career languished under the baleful gaze of now-President Ulysses S. Grant, who banished Thomas to the Pacific coast, where in 1870 he died of a stroke aggravated by his frustration at being underappreciated for his Civil War service.

Fellow 1st Cavalry Major John Sedgwick later served as a major general in the Union Army of the Potomac, where he achieved a certain mordant immortality at the Battle of Spotsylvania in May 1864, shaming his soldiers for ducking and dodging Confederate sniper fire. “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance,” Sedgwick scolded. An instant later a bullet struck him flush in the face, killing him instantly. His last words were shortened, falsely but memorably, to: “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this dis—.”

Major General Samuel Sturgis, who served as a captain under Sedgwick in the 1st Cavalry, won a signal victory for the North at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March 1862, a victory that preserved Union control of Missouri for the remainder of the war. Other Union major generals who had served on the western frontier included George Stoneman, Thomas J. Wood, and David S. Stanley—the same Stanley whose life Jeb Stuart saved at the Battle of Solomon’s Fork in 1857, when Stuart nearly lost his own in the process.

In this article, under a painting of two cavalrymen fighting, it says “Saber-wielding Civil War cavalrymen duel to the death over control of an American flag.” It’s actually a Confederate flag that they’re fighting over — the Stars and Bars (as opposed to the more famous Confederate battle flag.)