By Marc D. Bernstein

The Japanese looked unstoppable. Two divisions of the 15th Army had crossed from Thailand into Burma in mid-January 1942, bent on capturing Rangoon before the British could land reinforcements and block the seizing of the Burma Road.

Burma was critical to the entire Allied defense of the Far East. By taking Rangoon and then the Burma Road, the Japanese would cut the vital land link to China, where half of the Imperial Army was already tied down fighting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces. Burma was also the gateway to India, and Rangoon was the key to everything. In addition to being Burma’s administrative capital, it was a crucial communications and industrial center and had the only port capable of handling troop ships. The loss of Rangoon would mean the loss of Burma.

Organizing the Allied Defensive Forces

Opposing the two Japanese divisions fighting their way northward through the Tenasserim District of lower Burma was only the recently arrived 17th Indian Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Sir John G. “Jackie” Smyth, who had won a Victoria Cross in World War I. Smyth was a courageous and dedicated soldier, but he was a sick man. In September 1941, he had undergone an operation for an anal fissure and piles, which had gone badly. Although pronounced fit for duty, by January 1942 he was still in constant pain, and in the light of subsequent events, it has been speculated that his military judgment was affected.

Smyth’s immediate superior was Lt. Gen. Thomas J. Hutton, general officer commanding, Burma Army. Hutton had been a very competent chief of staff to General Sir Archibald Wavell when the latter had been commander-in-chief, India. Wavell had named Hutton to command Burma Army shortly after the outbreak of war with Japan in December 1941. But Hutton was untested as a field commander, and his responsibilities in Burma were extensive and went beyond simply issuing orders to troops. He had requested a corps commander, but it would be March 1942 before one arrived. In the meantime, Hutton exercised direct control over just two divisions, the 1st Burma Division and the 17th Indian Division. These would be augmented in February with the arrival of the 7th Armoured Brigade at Rangoon. The 1st Burma Division was tied down in the Shan States of eastern Burma near the Thai border, awaiting a Japanese attack along that axis of advance.

Hutton still reported to Wavell, but Wavell’s position had changed with the advent of 1942. He had been named Supreme Commander of ABDACOM, the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command now responsible for defending the huge swath of territory lying between India and Australia. Wavell established his new headquarters in Java, some 2,000 miles east of Rangoon. Further complicating matters was the fact that though Hutton was subordinate to Wavell operationally, for administrative purposes he still reported to the C-in-C, India, the newly appointed General Sir Alan Hartley. Wavell’s geographical remoteness was to prove very cumbersome during the five critical weeks that ABDACOM directed the defense of Burma.

The 17th Indian Division’s components were hastily assembled in Burma during January and February 1942. Essentially, the division consisted of the 16th, 46th, and 48th Indian Infantry Brigades, plus troops, such as engineers and artillery, that answered directly to division headquarters. Smyth also exercised control over the 2nd Burma Brigade during the early fighting, notably in defending the important city of Moulmein. But the division was not a crack unit. As one writer has noted, “It had been in existence only a few months, training for the Middle East,” and was “pronounced unfit to face a first class opponent by India’s Director of Military Training.”

Ironically, that same director of military training, Brigadier D.T. “Punch” Cowan, was requested by Smyth to serve as the 17th Division’s second in command. He arrived at the front in early February.

Retreat to the Sittang Bridge

As the Japanese 33rd and 55th Divisions pushed through Tenasserim, Hutton insisted that Smyth follow a forward defense strategy. This meant that the 17th Indian Division would seek to delay the enemy advance at every key river barrier in an effort to buy time for reinforcements to land at Rangoon. The strategy was dictated by Wavell himself. But Smyth considered it folly to try to hold such positions as Moulmein and Martaban against determined assault by a superior number of battle-experienced (in China) enemy troops. He favored early withdrawal to better defensive positions closer to Rangoon, most notably behind the Sittang River, just 55 miles east of the capital.

Despite the argument, Smyth was forced to comply with the strategy of delay. The Japanese succeeded in taking their early objectives and by February 15 had reached the Bilin River, 35 miles below the Sittang. There, Smyth’s men fought a furious four-day battle that temporarily checked the enemy advance. Hutton authorized a withdrawal across the Sittang on February 19, but one of Smyth’s units broadcast the withdrawal order in the clear, and the Japanese intercepted the message. On the night of February 19-20, as Smyth began his pullout from the Bilin River line, Lt. Gen. Seizo Sakurai, commanding the Japanese 33rd Division, sent his 215th Infantry Regiment on an end-run around Smyth’s left flank in an attempt to seize the railway bridge across the Sittang intact.

Curiously, although Smyth had for weeks advocated a more rapid withdrawal, he now hesitated at a crucial time. There were two clear routes to the Sittang. One followed a railroad track, and the other, further inland, followed the trace of a road. The latter was not paved, but Smyth decided to send virtually the entire division along the trace to the Sittang Bridge—and the 17th Indian Division was totally dependent on its road-bound motor transport. The Japanese, on the other hand, had few vehicles and could move rapidly overland through the jungle.

A Crossing Without “Any Sense of Urgency”

With the withdrawal from the Bilin already under way, Smyth outlined his plan for crossing the Sittang at a conference on the morning of February 21. A small bridgehead on the east side of the river was being held by the much-depleted 3rd Battalion, Burma Rifles. Smyth proposed to strengthen the bridgehead by sending the 4th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment there in trucks ahead of the rest of the division, to be followed by Advanced Division Headquarters, engineers, and a few other units. Then the 48th Brigade would move to within 7-10 miles of the bridge, while the 16th Brigade stayed put at the Boyagi rubber estate four miles west of Kyaikto (a town about halfway between the Bilin and Sittang Rivers), and the 46th Brigade would form the division’s rearguard. Smyth envisioned no units crossing the Sittang on February 21, and the entire division crossing the bridge on the next day.

Major General Ian Lyall Grant, as a young man a participant in the first Burma campaign, has written, “This was an astonishing plan in view of the danger, indeed likelihood, of a Japanese outflanking movement both north and south. It showed a complete lack of any sense of urgency in getting across the Sittang. It was apparently influenced by the desire to rest the troops, who were certainly very exhausted by their four days of fighting at the Bilin River. But the result was that, on this vital day, the leading troops would only march 11 miles, and half the division would scarcely move at all. Brigadier [R.G.] Ekin [46th Brigade] was horrified. He saw clearly that a terrible risk was being taken.”

Lyall Grant went on to observe that Smyth was making a serious mistake, and that “the answer must surely be that his illness had affected his judgement.” But, “There can be no doubt that if he was really ill, as he seems to have been, it was also his duty to hand over command. He had an able deputy at hand and many thousands of men were relying on his judgement for their lives.”

In fact, on February 8, Smyth had taken the extraordinary step of writing a confidential letter to Hutton requesting leave in India. He had also remarked to Cowan upon the latter’s arrival in Burma that he thought it might be necessary to relinquish command. Cowan had replied that doing so in the midst of a tough campaign would have a disastrous effect on troop morale, and Smyth remained in charge of 17th Indian Division.

Louis Allen, who also fought in Burma, has noted that Smyth “would not uncover the Kyaikto area until he had more definite information about the strength and direction of the Japanese advance. There was no traffic control formation at the bridge either, so he thought it inadvisable to send so much transport back at once.”

Whatever the true reasons might have been for it, Smyth’s decision to engage in a carefully staged retreat to the Sittang would prove very costly. Brigadier Ekin “was very suspicious of the apparent lack of Japanese follow-up along the road. This indicated to him not that the Japanese were being sluggish, but that they were out-flanking” Smyth’s division, but as Lyall Grant added, “Smyth did not agree. He thought that the tentative Japanese follow-up was the result of the casualties inflicted in the successful fighting on the Bilin.”

An Agonizing Withdrawal: Intense Heat and Friendly Fire

Because the Sittang Bridge itself was a railway bridge, the 1st Burma Auxiliary Force Artisan Works Company had been at work for a week bolting down planking on each side of the railway line to make it suitable for vehicle traffic. In addition, on Hutton’s orders, the bridge had been wired with explosives. But the charges were removed and stacked about 100 yards from the west end of the bridge when the planking work was undertaken. By February 21, the only engineers left east of the Sittang were a company of the Malerkotla Sappers and Miners, under the command of Major Richard Orgill. On the evening of the 21st, before the first vehicles of the division were scheduled to cross, Orgill received orders to prepare the bridge once again for demolition. He was instructed to have it ready to blow by 1800 hours, February 22.

The 17th Indian Division’s withdrawal to the Sittang during February 21-22 was an agonizing experience. One historian commented, “The heat was intense under a cloudless sky and the dust thrown up by their boots and the wheels of the transport grinding along at two miles an hour completely obscured the track ahead and clogged the ears and throats of the soldiers. The men marched like automatons, seldom speaking as their throats were so parched…. Enemy aircraft flew low above the track, bombing and machine-gunning with deadly precision.”

On the afternoon of the 21st, as the division plodded along the road from Kyaikto toward Mokpalin, a town just two miles southeast of the bridge, a disastrous friendly-fire incident occurred. Royal Air Force and American Volunteer Group planes appeared over the column and attacked it. A reconnaissance aircraft had mistakenly reported that a large number of vehicles spotted on a road heading toward the Sittang were Japanese, and both bombers and fighters were scrambled from fields at Magwe and Rangoon for an immediate strike.

The pilots did not realize that they were attacking targets west of their prescribed bomb line and that the Japanese were almost entirely lacking in motorized transport. The bombing and strafing went on for several hours, and by the end of it the 17th Division had suffered considerable casualties in personnel, plus the loss of numerous vehicles, pack animals, and vital radio communications equipment. The troops on the ground, thinking that the planes had somehow been captured and were being flown by Japanese pilots, had fired back and shot down two aircraft. It was a first-class fiasco.

Captain Bruce Kinloch of the 1/3 Gurkhas recorded, “I remember lying on the ground with a .303 rifle and firing at Blenheim bombers which were flying low and dropping bombs on the column. Tired men were kneeling, scorched and blackened by the flames and smoke and crouching in the flimsy shelter of smouldering trees at the side of the track while streams of tracer bullets from the multi-gunned fighters scythed through the branches with a high-pitched tearing snarl that merged into a continuous ear-splitting crescendo of sound as the planes screamed over again and again just skimming the tree tops, strafing and bombing without a moment’s respite. The earth heaved and shuddered under the muffled thud and roar of fragmentation bombs.”

The Japanese Supply Shortage

The Japanese, for their part, were also exhausted after weeks of campaigning, but they pressed on toward the Sittang, moving through the jungle both north and south of the retreating 17th Indian Division. A 15th Army operations order dated February 17 specified that the 33rd and 55th Divisions were to advance to the river and then wait for instructions.

Lieutenant General Shojiro Iida, commanding the 15th Army, stated, “I was then extremely worried … because of the increasing shortage of supplies. In order to pass through the rugged jungle of the Thai-Burma border, the quantity of equipment and supplies was reduced to a minimum…. Under these circumstances, it was quite impossible to attempt to march further forward beyond the Sittang.”

This was, of course, unknown to Smyth, Hutton, or Wavell. And it did not prevent the Japanese from moving with comparative lightning speed in trying to reach the east end of the bridge before what was left of the 17th Division’s vehicles and most of its fighting men could. Units of the Japanese 33rd Division would succeed in covering the distance from the Bilin to a hill overlooking the bridge in just 56 hours. Moreover, the presence of Japanese airborne troops had been observed in Thailand, and both Smyth and Hutton became concerned about a possible parachute drop west of the bridge.

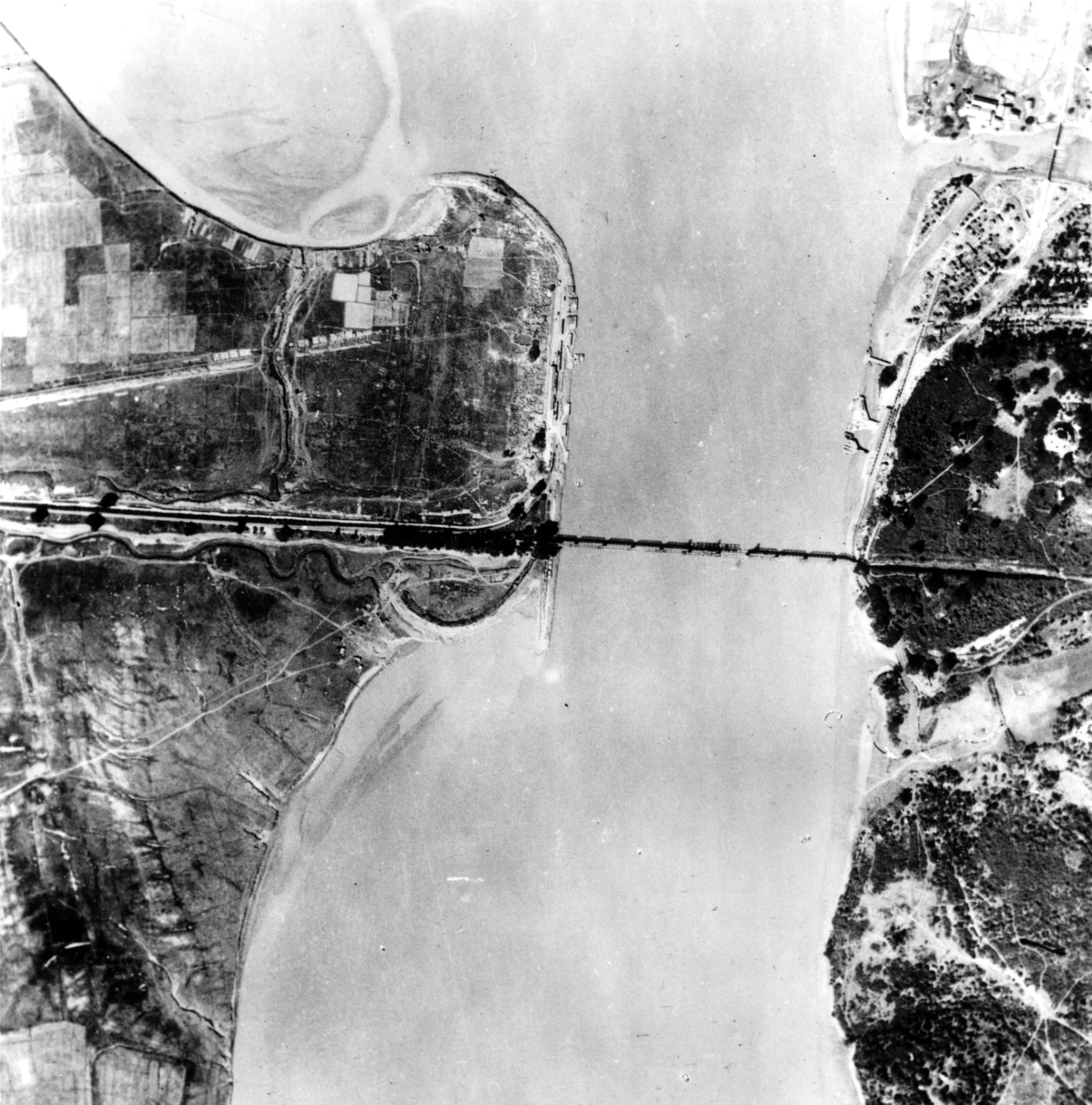

A flotilla of some 300 small boats had been assembled on the west bank of the Sittang to assist in moving the 17th Indian Division across the river. Three ferries also were moored on the east bank. Worried that the boats might fall into enemy hands, Smyth ordered his chief of engineers to destroy them, and the ferries were destroyed by Japanese Army Air Force bombing. The only way left for the whole 17th Division to cross the river was by the 550-yard-long bridge.

A First Strike at the Bridge

After the very trying day of the 21st, leading vehicles of the division began to cross the bridge at about 0200 hours on February 22. All went well for two hours, and then an accident occurred. An Indian driver of a three-ton truck mistakenly put his foot down on the accelerator instead of the brake, narrowly avoided plowing into an ambulance in front of him, and ran partially off the bridge’s planking. It took over two hours to clear the accident, during which time traffic on the bridge was at a standstill. Given the course of events, the time lost would prove critical.

By dawn on the 22nd, the 17th Division was strung out over 14 miles between the Boyagi rubber estate near Kyaikto and the west bank of the Sittang. Smyth, in fact, did not know where his units were, as division headquarters was unable to establish radio contact with them. This was most unfortunate, as the division would engage in three separate actions on the 22nd. One of these was in the bridgehead east of the bridge, while the others were near Mokpalin, two miles from the bridge, and farther east on the Kyaikto-Mokpalin road.

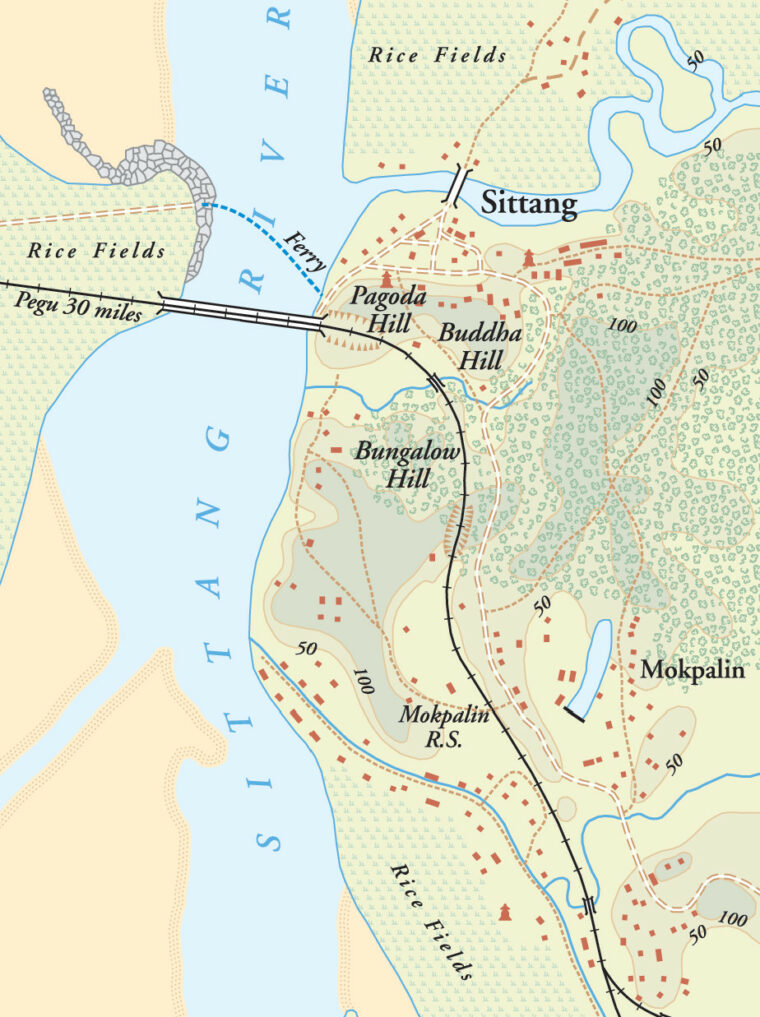

The Japanese 1st Battalion, 215th Regiment emerged from the jungle at 0800 and attacked Sittang village. Meeting unexpected resistance there, the commander of the lead company decided to occupy Hill 135, also called Buddha Hill, which dominated both the village and the approaches to the bridge. Another terrain feature, Pagoda Hill, stood between the Japanese and the bridge, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to move past it and seize the bridge. The 4/12 Frontier Force Regiment and a company of the 2nd Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment counterattacked, driving the enemy off Pagoda Hill and rushing up Buddha Hill before being driven back by Japanese fire. The Japanese reinforced their positions on Buddha Hill and could not be dislodged, but their first attempt to gain the bridge had failed.

The Fight for Mokpalin

About noon, Smyth put Brigadier Noel Hugh-Jones of 48th Brigade in command of all bridgehead troops. Hugh-Jones had been on the west bank of the river, but moved his tactical headquarters to the east end of the bridge. After suffering some casualties from heavy shellfire, Hugh-Jones decided to withdraw the bridgehead troops and his headquarters back to the west side of the river. Subsequently, the Japanese made another attempt to seize the bridge but were pinned down by fire from two platoons of the 1/3 Gurkhas attacking from the south. At 1530 hours, Smyth ordered Hugh-Jones to reestablish the bridgehead on the east side of the river. An assortment of units formed the new bridgehead force and set up a perimeter around the east end of the bridge.

Smyth had moved division headquarters considerably west of the bridge to Laya, about five miles from the river. This meant that he was almost completely out of touch with what was happening. Adding to his concerns, Hutton specified that he was to attend a meeting at Milestone 53 on the Pegu road, about 25 miles from the bridge, the next morning. Smyth gave Hugh-Jones full responsibility for defending the bridge, and his orders were that under no circumstances could the bridge be allowed to fall intact into enemy hands.

Meanwhile, Ekin’s 46th Brigade had been ambushed by the Japanese 3rd Battalion, 214th Regiment on the Kyaikto-Mokpalin road. It had been bringing up the division’s rear, but a one-mile gap had developed between the 46th and 16th Brigades along the road. At 0930 hours on the 22nd, the Japanese sprang their ambush. Two companies of the 3/7 Gurkhas tried to move around the block on the road, but their attack failed. After an hour-long firefight, Ekin decided to send some of his men overland through the jungle to Mokpalin, while part of the column tried to continue moving along the road.

The Japanese absorbed substantial casualties in the fighting and eventually withdrew, so part of 46th Brigade was able to reach Mokpalin with vehicles. The troops, including Ekin himself, who moved toward Mokpalin through the jungle, found the going difficult and split into small parties. Some eventually made it to Mokpalin railway station the next day, while others crossed the river independently. Casualties sustained by the 46th Brigade in the ambush and aftermath were heavy.

Brigadier J.K. “Jonah” Jones, commanding 16th Brigade, had led his own unit safely into the vicinity of Mokpalin, but in the town the 2/5 Gurkhas had come under fire from the north. The Gurkhas attacked and captured a small hill, then two companies continued on and launched an attack on Buddha Hill farther north. That attack failed. Then the 1/3 Gurkhas arrived and launched their own attack toward both Buddha and Pagoda Hills. It was at this point that the Gurkha attack blocked the second Japanese attempt to capture the bridge, but the Gurkhas failed to dislodge the enemy from Buddha Hill and were ordered by Jones to pull back.

This proved very difficult to do, and two companies of the 1/3 Gurkhas were isolated near Buddha Hill. These Gurkha units actually were part of Hugh-Jones’s 48th Brigade, but because they were in the vicinity of Mokpalin, Jonah Jones had taken control of them when he and his 16th Brigade arrived at that location. On the evening of the 22nd, Jonah Jones set up a defensive perimeter around Mokpalin and then planned for yet another attack to the north to commence after first light on February 23. It was to be supported by nearly all the divisional artillery, which was near Mokpalin, but the attack never came off.

Blowing the Bridge

Jonah Jones at Mokpalin was not in communication with Hugh-Jones at the bridge, though the distance separating them was only about two miles. Hugh-Jones, in fact, had been led to believe from the reports of a Gurkha officer and some stragglers that both the 16th and 46th Brigades had been overrun. The bridgehead force, under Hugh-Jones’s control, was considered weak and would get weaker when two companies of the 1/4 Gurkhas were sent west across the bridge at dawn on the 23rd as protection against the feared enemy airborne drop. So Hugh-Jones felt severe pressure to blow the bridge. A renewed Japanese attack was thought probable.

At 0200 hours on the 23rd, Hugh-Jones summoned Major Orgill of the Malerkotlas and asked him if he could guarantee a successful daylight demolition of the bridge. Orgill replied that he could not guarantee it, but that he would do his best. The Malerkotlas had worked throughout the 22nd, under sporadic fire from Buddha Hill, getting the bridge ready to be demolished. Although the bridge consisted of 11 spans, only numbers 4, 5, and 6, counting from the east bank, could be prepared due to a shortage of explosives, wire, and fuses.

Orgill could not guarantee a successful daylight demolition because only span number 5 could be prepared with electric detonators and an instantaneous fuse. The other two spans were set with long safety fuses and wired for a sympathetic detonation. If Orgill’s men came under heavy fire and were casualties, the fuses to numbers 4 and 6 might not get lit, and only span number 5 would detonate. Dropping just one span would be inadequate.

Brigadier Cowan, as Smyth’s number two, received a frantic telephone call from one of Hugh-Jones’s staff officers not long after Hugh-Jones’s conversation with Orgill. Authorization was requested to blow the bridge before daylight. Cowan woke Smyth, and the latter considered the issue for five minutes before ordering Hugh-Jones to destroy the bridge. Smyth later claimed he was well aware that a substantial part of his division was still on the far side of the river. Eight infantry battalions plus most of the motor transport and divisional artillery were east of the bridge.

The bridgehead force was ordered to withdraw to the west bank, and at about 0400 hours on February 23, according to his own recollection, Lieutenant Bashir Ahmed Khan of the Malerkotlas pressed down on a plunger and fired the charges. Spans 5 and 6 dropped into the river, and two-thirds of the 17th Indian Division was cut off.

Drownings in the Heavy Current

On hearing the demolition, all firing on the battlefield momentarily ceased. Both sides knew what destruction of the bridge meant. The Japanese had no immediate plans to attack toward the bridge and did not do so on February 23. If any of the 17th Division’s Indian, Burmese, Gurkha, and British troops east of the river were to cross it, they would now have to swim or float on hastily constructed rafts. That meant abandoning almost all equipment, including small arms.

Many Gurkhas, in particular, could not swim and drowned in the river, but some did manage to cross the destroyed bridge with the assistance of ropes. Brigadier Jonah Jones had at first hoped to delay an organized crossing until the evening, but the pressure of events forced him to schedule an afternoon evacuation. He was especially concerned that the wounded be accommodated on rafts, if possible. The Sittang is a tidal river, but February is the dry season and the river tide is low in the afternoon. However, a strong current in the vicinity of the bridge made swimming difficult as thousands of men took to the water throughout the day. Even strong swimmers averaged about two hours in the water to complete the crossing. Those who could not or would not attempt it were captured or fought to the death.

“A Dog-Fight in the Jungle”

When it was over, the 17th Indian Division was thoroughly wrecked. About 5,000 troops were dead, missing, or captured. Of the original division, there remained only 80 British officers, 69 Indian and Gurkha officers, and 3,335 other ranks. They possessed just 1,420 rifles, 56 light machine guns, and 62 Thompson submachine guns. As late as March 19, the partially reconstituted division had just 6,700 effectives.

The Japanese, who were exhausted, waited a week for logistical reasons, then sent a regiment 18 miles north of the bridge to ford the river at Kunzeik, while three regiments crossed at the actual bridge site, where engineers had built a wooden footbridge across the dropped spans. They then drove on Rangoon, entering the city on March 8. So, for a variety of reasons, Smyth’s decision to blow the Sittang River Bridge proved both premature and ultimately unnecessary.

Smyth later described the Sittang battle as “a dog-fight in the jungle. Nobody above the rank of company commander could exercise any control.” Shortly after the bridge incident, Wavell removed him from command and forced him out of the army, depriving him of his general’s rank. Smyth’s military career was ruined, though after the war he became a Member of Parliament and was given the honorary rank of brigadier for his earlier accomplishments. Hugh-Jones, who took counsel of his fears and requested permission to blow the bridge in the early morning darkness of February 23, never recovered from the shock of the division’s destruction and committed suicide after the war. Hutton, who learned during the fighting that he was to be replaced as Burma Army commander by Lt. Gen. Sir Harold Alexander, said, “There is no doubt that the battle of the River Sittang was nothing less than a disaster.”

Wavell was in the process of resuming command in India after the dissolution of ABDACOM. He summed up events succinctly: “The battle of the Sittang bridgehead on February 22nd and 23rd really sealed the fate of Rangoon and lower Burma. From reports of this operation which I have studied I have no doubt that the withdrawal from the Bilin River to west of the Sittang was badly mismanaged by the headquarters of the 17th Indian Division, and that the disaster which resulted in the loss of almost two complete brigades ought never to have occurred.”

Long after the war, Smyth persisted in antagonizing many participants and observers by claiming that his division had not been destroyed at the Sittang. His actions and beliefs remain highly questionable. But his dilemma about the bridge in late February 1942 was a real one. As Field Marshal Viscount William J. Slim was to write, “It is easy to criticize the decision; it is not easy to make such a decision. Only those who have been faced with the immediate choice of similar grim alternatives can understand the weight of decision that presses on a commander.”

Marc D. Bernstein is the author of Hurricane at Biak: MacArthur Against the Japanese, May-August 1944, and has written extensively on modern military and naval history. He lives in California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments