By Bruce Ware Allen

In the late summer 1541, 40 warships appeared off the shores of Sardinia, part of a grand armada gathered by Charles the V of Spain, Holy Roman Emperor. Local residents, desperate to impress the important guests, scoured the countryside for a suitable gift. It took a while, but in the end they presented Charles with a two-headed calf. Many of those present took the gift to be a bad omen.

They were right to be concerned, but the two-headed calf was the least of their problems. The armada was the result of nearly a year’s planning, far longer than usual for Renaissance-era warfare. Charles might have set off earlier, but he chose to pass the summer at the Diet of Regensburg, listening to the leaders of his empire’s Catholic and Protestant factions trying to reconcile questions of Christian doctrine. His military deputies, meanwhile, were getting more and more nervous. When would Charles follow the pope’s advice and head east to battle the sultan?

It was not until June 29 that Charles was finally able to leave the theological debates and head south. His target was Khairedihn Barbarossa, governor of Algiers, leader of the Barbary corsairs, and a man known throughout the Christian Mediterranean as the “King of Evil.“ Barbarossa was the inevitable result of policies dating back to Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, Charles’s grandparents. In 1492, Spain had expelled all Jews and many Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula, resulting in a mass of angry, footloose Spanish Muslims settling on North African shores and preying on Spanish ships. It was fast money, and their success attracted sailors from the east, including the so-called Barbarossa brothers.

Sons of a retired janissary from the island of Lesbos, the brothers arrived at the city of Tunis in a pair of eight-oared vessels not much larger than long boats. They were, however, large enough to capture merchant ships, and the brothers went from success to success, gathering like-minded adventurers at every turn. In time, sheiks of the various North African cities employed the Barbarossas to kick out Spanish troops from their strongholds. It was not always easy work. The elder brother, Aroudj, lost an arm to a Spanish cannon ball (he replaced it with a prosthetic made of silver). Eventually, Aroudj ended up ruling Algiers after assassinating the sheik who had hired him to protect it.

Aroudj went too far, however, by taking the city of Tlemcen, dangerously close to Oran. The sheik of Oran, together with his ally, Charles V, gathered a considerable army and marched on the city. Aroudj fled, casting gold coins behind him as a distraction. The army ignored them. Eventually cornered, Aroudj went down swinging, “to the very last gasp, like a lion,” according to one observer’s account. Aroudj’s corpse was put on display in Spain to reassure the populace. His cape went to Cordoba, where it adorned the Chapel of St. Jerome.

That might have been the end of the matter, had it not been for his younger brother, Khairedihn. Not as vicious as Aroudj, Khairedihn proved to be a better tactician, strategist, and political manipulator. As soon as he got news of his brother‘s death, he gathered the people of Algiers and announced that he could do no more for them. The people begged him to stay, and he agreed, but only on condition that he obtain Ottoman protection. Within weeks, Sultan Selim blessed the venture, sending 2,000 janissaries and 4,000 militia to garrison the city and elevating Khairedihn to governor of the new Ottoman eyalet, or border state.

For the moment, Selim was busy with land campaigns in central Europe and Persia. He had little control over the petty sheikdoms of North Africa and was happy to let pirates and corsairs distract his Spanish enemy in the western Mediterranean. Day to day, there was little change in the coming years. Algiers adopted the administrative patterns of the Ottoman Empire, raiding continued, and a new sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, eventually settled onto the throne.

Things might have gone on like this indefinitely if not for two serendipitous events. In 1528, Genoese Admiral Andrea Doria approached Charles and offered his services, as well as those of his considerable personal fleet. Doria was the West’s answer to Khairedihn, an independent condottiere who fought for pay. Until recently his chief European ally had been King Francis I of France, but the king had lost Doria’s services by pointless insult. Charles proved a better customer.

Three years later, the fighting knights of St. John accepted Charles’s offer of a new home on the island of Malta and the city of Tripoli. In exchange, they paid annual rent to the emperor. Charles was happy to have a self-financing group of soldiers to protect the approaches to Sicily, and the knights, having been kicked out of Rhodes in 1522, were happy for a place to restart operations. Although neither the admiral nor the knights were under the emperor’s direct command, they would both prove more than ready to take on the Muslim enemy when called. Charles was perfectly placed to quash the Barbary corsairs once and for all.

It didn’t turn out that way. Instead, the knights headed east for short raids on an Ottoman city, Methoni, in what is now Greece. In true pirate fashion, they burned, looted, and dragged off captives for ransom or the galley benches. The following year, they joined Doria on a sanctioned trip to Koroni, also now part of Greece, which they seized for the Pope. (Charles decided the place was too great an expense and let it slide back after two years.)

If the booty was trivial, the political consequences were catastrophic. Suleiman, heretofore content to leave the western Mediterranean alone, now decided that he must address the insult. His fleet, chiefly dedicated to policing the eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea, would have to expand into the west. Money was no object, and he was fortunate in having Khairedihn on his side. No longer a mere pirate or corsair, Khairedihn was promoted to kapudan pasha, grand admiral of a sovereign empire.

The new fleet started off well, ravaging the Italian coast—neither Doria nor the knights had the nerve to come to and fight—and showing just how vulnerable Europe was. Eventually, Khairedihn headed south to his real target, the city of Tunis, which he plucked with contemptible ease from its dissolute ruler, Muley Hassan, in 1535. But, like Tlemcen, this was too close to Spanish interests. Charles roused himself and the next year retook Tunis, captured 80 of Khairedihn’s ships, and reinstalled the sycophant Muley Hassan as his puppet. The triumph was marred only by Khairedihn’s escape and subsequent return to raiding Charles’s coastlines.

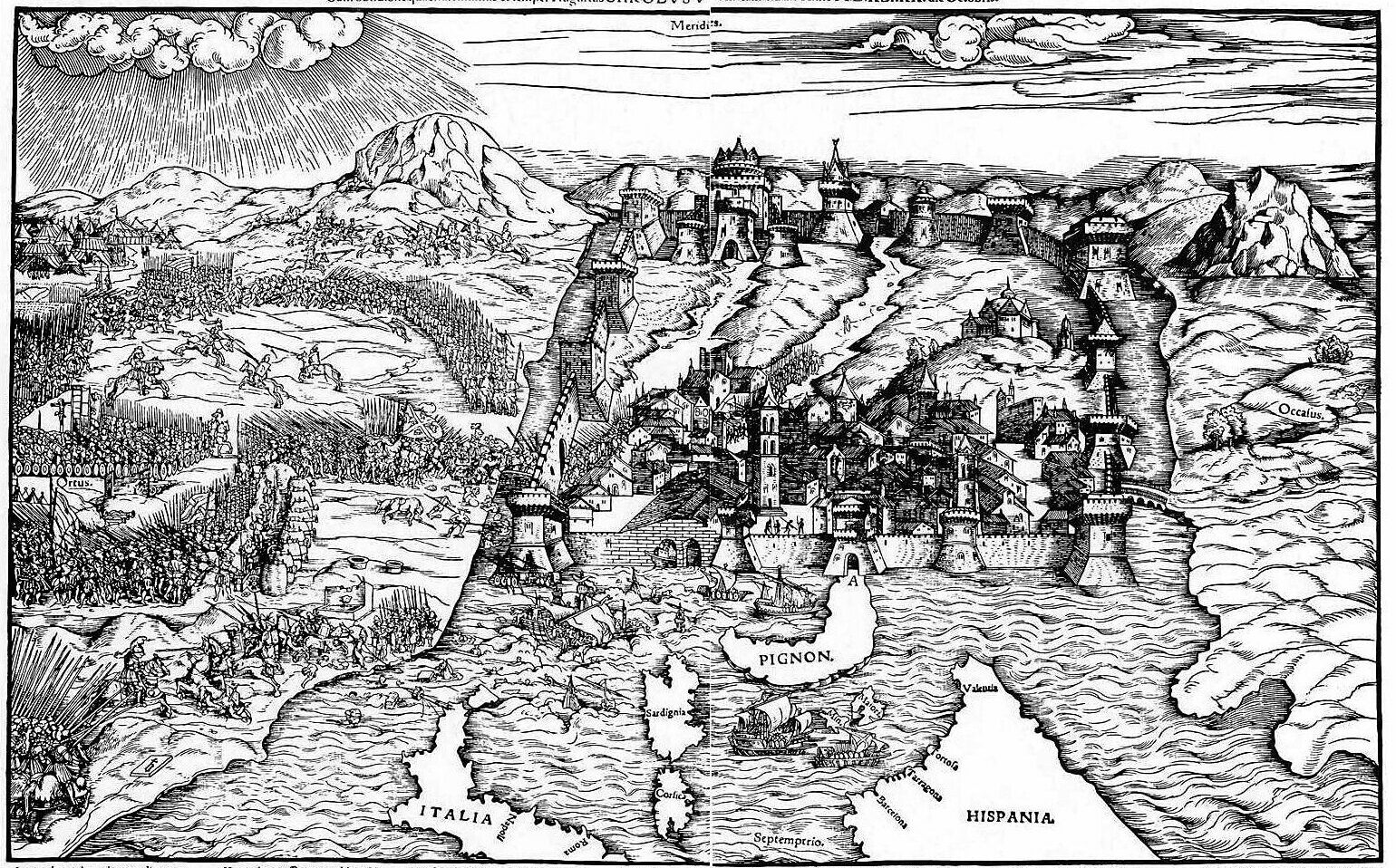

It was another five years before Charles decided to match his success in Tunis with the capture of Algiers. The decision was not universally welcomed. The Pope urged him to push back Suleiman on land. Doria advised that he continue a policy of raiding the eastern Mediterranean. Charles was not swayed by either argument. He was, however, cautious. The Ottoman fleet had grown in these past years, and Charles did not want to risk his own ships in an all-or-nothing sea battle. He tarried that summer at Regensburg until July 29, then made for the coast. Once he had arrived at the water’s edge, contrary winds kept Charles from heading westward. By October 15, the armada was still in port in Majorca, due north of Algiers. Charles’s lieutenants—Andrea Doria and Hernan Cortez among them—were nervous. To sail so late in the season was a risk that few professional sailors were willing to make.

But Charles, a man of iron faith, believed he had God’s favor. He also knew how much money he had spent. True, his low-hulled galleys would have to cross 100 miles of potentially stormy seas. But to counter him, the Ottomans would have to get their fleet up to speed and send it more than 500 miles. He was confident that they would have neither the time nor the courage to try. Without the threat of an Ottoman relief force, he would be able to take Algiers undisturbed.

Charles ordered his 24,000 men, Spanish foot soldiers, German landsknechte, Italian condottiere, knights of St. John, and several cavalry units onto 290 ships and headed south. He would have preferred to have been facing Khairedihn himself, but the wily old corsair was safely in Constantinople, leaving Algiers in the hands of his lieutenant, Hassan Agha.

Hassan knew that Charles was coming. The emperor had tried to buy him off through Spanish intermediaries in Oran. Hassan had turned him down and did not seem overly concerned at the prospect of invasion. Hassan concentrated on the upcoming wedding feast of his son, a magnificent affair of music, feasting, and games to which a good part of the city was invited. Only after the party was over did Hassan set about ordering defensive measures. Anything useful to the enemy outside the walls was destroyed, including Hassan’s own garden. All local inhabitants and visitors were given weapons and put on the wall.

Even Hassan must have been surprised at the spectacle of the fleet as it came into view, “so large,” wrote a Muslim chronicler, “that they could not be counted.” As Doria and others had predicted, the weather was highly unstable. The ships dropped anchor in the wide bay seven miles off the city, but rough waters made it impossible to offload men and cargo.

For two days, the inhabitants of Algiers could look out over the white walls and see the invading armada bouncing on an excitable sea. At least one ship sank—Muslims claimed it was Christian, Christians said it was Turkish. Mass was held aboard ship on October 23, and as the sun came out, Charles and his men were finally able to go ashore.

Getting the men ashore was one thing—getting their equipment to them was quite another. The mammoth siege guns, vital for taking down city walls, needed a calmer sea and a secured landing zone for offloading, and Doria was unsatisfied with current conditions. So with little more than their personal weapons, the soldiers marched west for three miles, Spanish, Neapolitans, and Sicilians in the van, Italians and knights in the main, and Germans as the rear guard.

Charles soon learned that Hassan had not been utterly passive in his defense tactics. Some men of the armada drank from a nearby stream, and as soon as they had drunk, they fell over dead. Engineers headed upstream and found the spring source in the hills had been dosed with arsenic. Nor was that all. Berber horsemen quickly attacked, firing spears and arrows to draw the invaders out of formation, then picking off the isolated men at leisure.

On October 24, Charles sent a herald under white flag and demanded surrender. Hassan, born a Christian, was invited to return to the faith and join the empire. The herald also reminded Hassan what he could expect if Charles took the place by force: utter destruction and extermination. Hassan refused. He had 1,000 janissaries and 5,000 armed auxiliaries on hand, and he also claimed to have fate on his side. He told the herald that, years before, an old enchantress had predicted that any Christian emperor who invaded “out of season” would be devastated.

Charles was not put off by other men’s superstitions. Doria moved his ships closer to shore to offload heavy artillery and other machines of war. It began well, but by afternoon, gray clouds moved in and it began to rain. Winds of uncommon fury kicked up the sea. Ships rose and fell on waves, straining their anchor cables, their passengers terrified of the rocky shore. On land, the entire force was without tents and shivered against the gale. Gunpowder turned to useless paste. Sleep was out of the question.

The following morning the weather broke again, and Sheik Sidi Said Cherif, commander of the forces within the city, climbed the walls of Algiers to inspect his enemy. He liked what he saw. His own men and horse were warm and rested, their powder dry. The Christians were stiff and cold and seemingly ripe for slaughter. He ordered the southern gates of Bab Azun opened and a squadron of cavalry to charge the enemy with sword, lance, and arquebus.

But Said Cherif had reckoned without the terrain. If the rain had chilled the Christian soldiers and ruined their powder, it had also saturated the ground. Mud slowed down the horses enough to equalize the fight. Advantage shifted. The open gates became the objective, and Christian knights charged toward them, close on the heels of the retreating Muslim cavalry. Cannon fire and scattered shots from the high walls dispersed the knights.

The Christians were not about to give up. Throughout the ordeal, Charles stood up like a seasoned veteran. Doria once more led back the ships that had survived the storm and approached the shore with provisions for the hungry troops. Again the weather turned. Another violent storm ravaged the fleet and sent ships crashing against the rocks. For hours, men watched as the fleet was torn apart. Terrified crews wanted to drive the ships onto the sand and take their chances on shore.

Soon, for miles up and down the coast, ships of the great fleet rolled onto the sands and rocks, and all the carefully packed guns, tents, hardtack, vegetables, wine, oil, and other materials began washing ashore. Scavengers emerged from the landscape and attended to both the detritus and to the exhausted castaways. Algiers had a ready market for slaves and hostages. The mistress of the officer Don Antonio Carriero, weighed down with waterlogged rich clothes and many jewels, managed to drag herself to shore but was killed by the scavengers, who found her too bulky a burden to take back with them.

The next morning, October 26, a messenger rode into camp with word from Doria. A staggering 140 vessels were either shattered on the beaches or at the bottom of the sea. The admiral had gathered the remainder 12 miles down the bay at Cap Matifou, where he would pick up anyone who could manage the trek. Charles decided that it was time to fold his hand. He lacked men, guns, ammunition, and food. To tide over his men, he directed them to slaughter and butcher their prize Spanish horses. Then they began the 12-mile retreat.

It took the army three full days to reach Doria. As a consequence of the rain, normally dry riverbeds had become all but impassible torrents, flood plains had become marshes. When the troops and hangers-on reached the El Harrach River, midway to their rendezvous, they found that flash floods had washed out the bridges. It took skilled engineers working with lumber from broken Spanish ships to rig a way across. All the while, Berber horsemen hectored the sad procession, dashing in and picking off stragglers. Knights of St. John protected the rear as best they could, losing 74 of their number in the process. Cortez, for whom this would be the final campaign, lost a bag of emeralds he had brought back from the New World.

Once the exhausted and tattered survivors reached Cape Matifou, it was quickly discovered that there wasn’t enough room on the boats for everyone. All remaining horses were killed. Those deemed excess human cargo remained on shore and watched as the last of the long boats carried the lucky few to the safety of the galleys. Arab sources claimed that 1,300 Christian women and children were taken into slavery, leaving one to wonder what so many women and children were doing there in the first place. Christian sources claimed, less believably, that all were killed on the beach.

As the ships set out one more time, yet another storm arose, and in a final humiliation, one of the Spanish vessels sank with 400 men on board. The remaining fleet weathered the storm and struggled down the coast to Bougie, where an anonymous agent for Charles’s perennial rival, Francis I of France, assured his monarch that the few survivors were reduced to a diet of dogs, cats, and grass. Charles resigned himself to the inscrutable will of God; he would never raise another armada.

Algiers remained the staging center for Barbary corsairs for the next 300 years, sending pirates out as far afield as Ireland in search of infidel hostages and foreign booty. Christian countries brokered deals with the local sheikhs to protect their own ships and attack their competitors. But by the early nineteenth century, the game had gone on too long. American and British warships forced the issue, and in 1830, France, Charles’s longtime enemy, annexed the city and put an end to the scourge that Charles had sought unsuccessfully to eradicate three centuries earlier. Perhaps he really had been cursed.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments