By Steve Ossad

A few months after the Normandy campaign and with other fronts competing for the American public’s attention, Lt. Col. S.L.A. “Slam” Marshall, a hard-living Chicago newspaperman, World War I veteran, and deputy historian in the European Theater, hand carried the first of the War Departmemt campaign publications, Omaha Beachhead,to General Omar Bradley. Based in part on Slam’s field notes as witness to the Allied invasion and lodgement in Normandy, he was told First Army, which planned and carried out the operation, would have to review the draft. Screwing his courage to the wall, Slam confronted the three-star commanding general: “Then will you instruct that they should question errors in fact but not delete an interpretation simply because it is disagreeable?”

In Slam’s view, “Omaha had not been a glittering triumph for our forces. There are few more brutal battles in the annals of America at war. Mistakes had been made and disaster had been narrowly averted.” Six weeks later, the report was back at the War Department, accuracy improved but otherwise untouched. It was a model and honest attempt at an objective analysis and paved the way for publication of “a more candid official history than has been written of the armies and generals heretofore.”

As tame as official histories sometimes appear now, for the historians writing the first drafts of World War II history this was an exhilarating moment. That feeling would not last, at least for Slam, and he became a critic of Bradley’s generalship.

At 0900 on August 1, 1944, Omar Bradley bade farewell to the staff at First Army, and at noon 12th Army Group became operational at Saint-Sauveur-Lendelin, three days after the previous German occupants had vacated the premises in haste. To the relief of General Courtney Hodges and most others at First Army, now working very smoothly in spite of its many idiosyncrasies, Bradley took no staff except for his official family (two aides, driver, cook, pilot, valet) and Red O’Hare, the G-1 (personnel), an aggressive outsider who joined the II Corps after Sicily from Governor’s Island and was never popular among the other GI’s. All of the uncertainty about who would command the American armies was over for the moment—except in the mind of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

Twelfth Army Group was formed on the Continent after D-Day with a command structure responsible for multiple American armies fighting in France. It was the successor to First Army Group, which had been activated with General Bradley in command in October 1943. The activation of 12th Army Group furthered the transition of American command from British Field Marshal Montgomery. During the early phase of the fighting in Western Europe, Montgomery had commanded all Allied ground forces. However, as the Allies pushed toward the German frontier, 12th Army Group was organized and ordered to report to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, who assumed direct overall command of Allied operations on the Continent on September 1, 1944.

Letter of Instruction #1 from 12th Army Group activated the U.S. Third Army with General Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps in place and another corps in transit and ordered General George S. Patton to swing southwest through the Avranches gap opened on July 31, 1944. Unleashing his mechanized cavalry and armor, Patton would secure the Brittany ports, especially Brest, and scour the peninsula of enemy forces before turning eastward along the Loire River. First Army, under Bradley’s deputy and understudy Hodges, would pivot to the left, driving back the Germans to the city of Vire with his three corps already on the line.

Bradley knew Courtney Hodges well, going back to the days when they served together under Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall at the Infantry School. They were longtime hunting and fishing buddies, both crack rifle shots, and knew the terrain and game around Fort Benning, Georgia, as well as anyone. Each played at or under par on most Army golf courses, many of which they played together. A West Point dropout from the class of 1908, Hodges caught up quickly, rising from prewar private to lieutenant colonel in World War I. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross as a battalion commander in the 6th Infantry Regiment in the Meuse-Argonne in November 1918. Serious, reserved, and quiet, everyone described him as “courtly” (pun intended), a gentlemen, and at age 57 he looked and spoke like a small town accountant, unimpressive in a cast of fascinating military celebrities.

Everyone knew that Hodges was a conservative believer in the official doctrine. One word and style summed it up: infantry. From instructor at Benning to chief of infantry and commandant of the Infantry School, Hodges was reliable, steady, cautious, a sound tactician, and good planner. Not a man to take dramatic risks, he willingly bore the brunt of battle while Patton hunted glory because he knew that what he was doing was key to winning the war. He was the tackle, and Patton was the end.

Bradley had a real blind spot about Hodges that went far back, based on common interests, experiences, world views, and genuine affection. Junior to Hodges in regular Army rank and personal status, even after Africa, Sicily, and taking over First Army, Bradley deferred to him in public, addressing him as “Sir” throughout the war.

Evaluated as an Army commander, history has not been kind to Hodges in spite of efforts to redress the disparity in attention paid to Third Army and the dominating image of its commander. Hodges has been described in a broad range from the generous “lacking in presence” to the harsh “clearly in over his head.” The proverbial man behind the scenes, he eschewed publicity and relied on the advice of a few advisers, especially his chief of staff, General Bill Kean, originally added to the team by Bradley when he took over II Corps and to whom Hodges delegated, or surrendered, much day to day control.

Kean, a ruthless, driven, and humorless administrator, was quietly mocked for some strange personal quirks, for example, an annoying addiction to peanut butter, which had to be specially procured. Called “Captain Bligh,” an unflattering reference to a real life movie character, Kean enjoyed his commander’s respect. Hodges also relied heavily on fellow Benning alumnus General Joe Collins, his most valued corps commander and a favorite of Bradley, Supreme Commander General Dwight Eisenhower, and Marshall. Everyone knew the driving force behind First Army’s more aggressive and maneuver-based operations was Collins’s VII Corps, usually spearheaded by General Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division.

By July 27, the main enemy resistance to Operation Cobra, the Normandy breakout, was vanquished. The Allies had taken Coutances and Avranches and opened the way for the great offensive. Badly wounded in an RAF Hawker Typhoon strafing attack on July 17, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, commanding German Army Group B, was slowly recuperating. Despite his fearsome reputation, his effect on the battle had been minimal, and after the assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, he disappeared as the feared adversary haunting the Allies, especially Montgomery and the British.

More important, whatever their reasons, OB West and Army Group B delayed too long in bringing reinforcements to Normandy. It was not until July 27 that Hitler finally released some Fifteenth Army divisions to Normandy. The vast Pas de Calais deception had pinned the Führer’s attention opposite the phony Army Group “stationed” at Dover for more than six weeks, beyond any possible expectation or prediction, and remains the greatest operational battlefield deception in history.

When the American armored columns struck out, the enemy withdrawal was so sudden and disorganized that no defense in depth was possible. Consequently, Patton’s columns of mechanized reconnaissance units probing ahead of the armored divisions met little resistance in the Brittany peninsula until they came to the ports. As expected, the Germans fell back to Brest, St. Malo, Lorient, and St. Nazaire, which they defended as fortresses. The Allied planners were continually searching for answers to growing supply pressure and envisioned the Brittany ports supplying the drive east to the Seine River. That territory would provide ample space for air and supply bases to support the advance to the German border, the Rhine, and beyond.

With corps cavalry groups and squadrons protecting the flanks along with mechanized infantry, Third Army whirled westward with infantry mopping up some opposition around Rennes. Montgomery had finally broken free of Caen and was moving south, which put an end for the moment to the attempts by Air Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder and others to have him replaced by Sir Harold Alexander. Ike and Bradley now pushed hard for General Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army to “be more aggressive” in support of Hodges, but without success.

One piece of good news where little was usually found cheered all: the weather was hot and dry, and inland from the sea there was little fog. Fighter bombers mercilessly attacked all enemy daylight concentrations and movement, further slowing the retreat that was degenerating into a rout. Under the staggering blows of the IX Tactical Air Command and VII Corps, the enemy left flank crumbled, widening the breakout.

On August 3, 1944, Bradley changed his mind about the ports and issued Letter of Instruction #2, halting Patton’s drive into Brittany and shifting Third Army’s weight to the drive east, with a single corps (three infantry divisions) left behind to protect the southern flank of the 12th Army Group. Soon after taking command, Bradley had his first battlefield difficulties with Patton. During a visit to newly established Third Army headquarters, Bradley saw a gap in his lines developing with the shift in plans and ordered a division to plug it along with coordinating orders to other divisions.

That was going over Patton’s head, an action seldom taken though not unprecedented. Patton was out in the field when the situation developed, so Bradley just left word with Patton’s chief of staff and at VIII Corps, most of all savoring the moment: “I got even with Patton.” It was a signal of Bradley’s continuing frustration with Patton’s independence and cavalier approach, although he graciously acknowledged he would have done the same thing and did not complain.

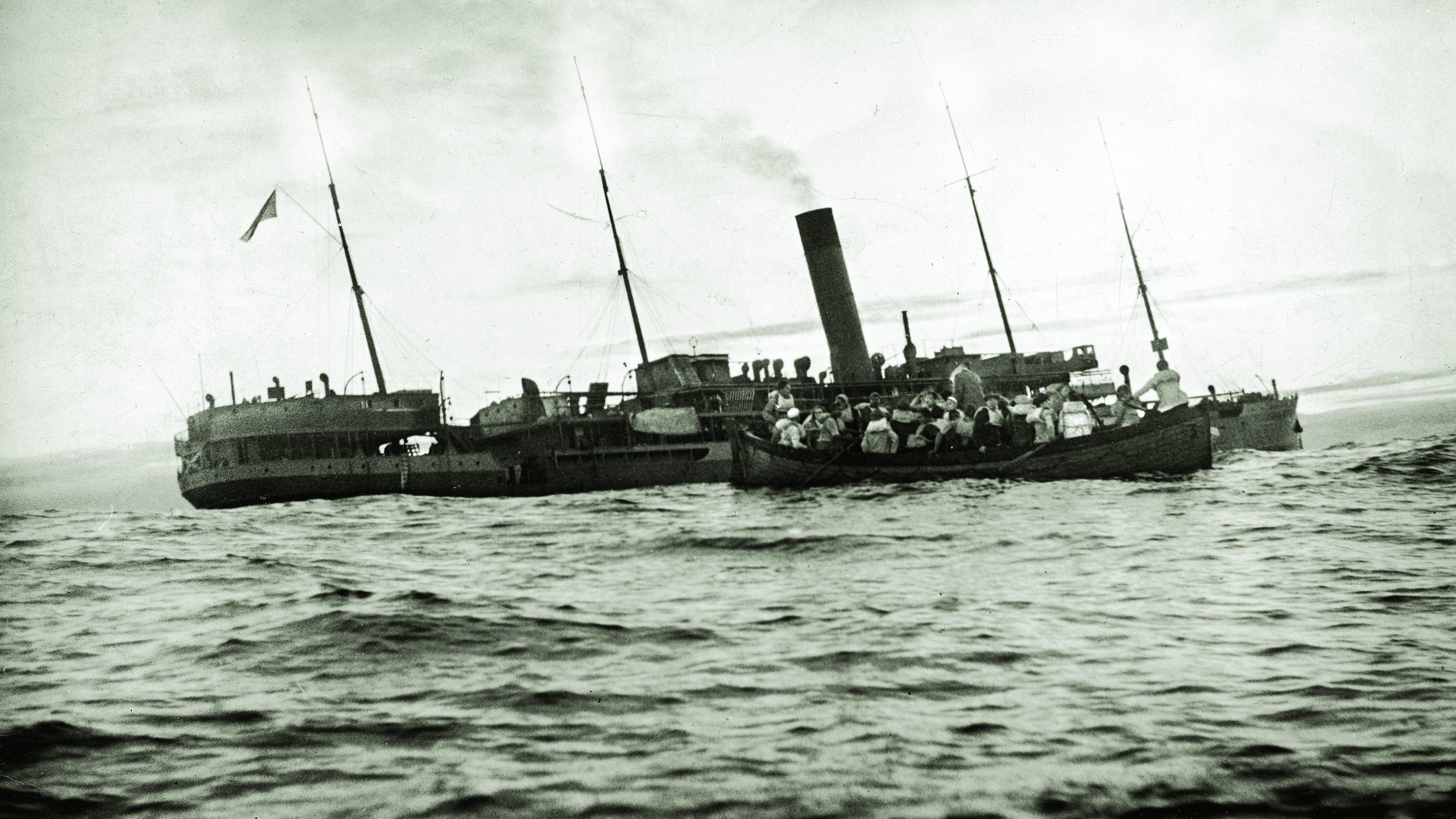

Even as he turned his main strength away from Brittany, there was criticism of the original plan. Bradley’s defense was mostly logistical; the Americans needed 750,000 tons of supplies per day, and almost all of it came over the beaches, while the small ports were subject to disruptions, especially by the weather. The storm of June 19, 1944, wrecked the American Mulberry artificial harbor at Omaha Beach, reminding everyone of the frailty of the supply line. Cherbourg was reserved for Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, so there was no margin of error. Supply by air was limited to about 1,000 tons a day and only useful for tactical situations, and even that was subject to other requirements for the limited transport fleet of Douglas C-47 transport planes.

The Germans had already demonstrated at Cherbourg that when assaulted they would destroy the port facilities before surrendering them, but critics complained that failure to seize the ports, regardless of the cost and destruction, prevented their use for many weeks longer than if they had been taken in the first rush. SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) always believed that Brest was necessary, and the status of other alternatives, such as Antwerp, remained uncertain.

Grasping the importance of exploiting the German retreat, Bradley calculated that it was more important to unleash Patton to keep them on the run rather than take the ports immediately, a decision strengthened by his confidence that the logistics train, especially ammunition, would keep up. When it came, the fight to take the ports, especially Brest, was bloody, a diversion, and well to the rear of where the real war was happening. To some it was an inauspicious beginning and a waste of Third Army’s mobile potential at the start of the breakout, but in his first moments as Army group commander Bradley was flexible, adapted quickly to the tactical change opened by the German collapse, and changed the plan on the fly, intervening against doctrine when he thought that necessary.

American history provides few models or even formal guidelines for an Army group commander. During his final campaigns of the Civil War in Georgia and the Carolinas, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman commanded three field armies—the Cumberland (General George Thomas), the Tennessee (General James McPherson), and the Ohio (General William Schofield)—and was in many respects the U.S. Army’s first Army group commander, though the scale of his operations was small. His army group never numbered more than 100,000 men, smaller than II Corps at Bizerte, and he faced no complicated combined arms, joint planning issues, or Army group boundary problems.

U.S. General of the Armies John Pershing, still the highest ranking ground soldier in American history, except possibly George Washington, barely deserves the title based on a few weeks during which he commanded two American armies, 500,000 men, at the end of World War I. After the Great War, there had been some study and discussion at the Command and General Staff School about doctrine and organization of large units, that an Army group should direct but not conduct operations … it should confine itself to broadly stated “mission orders,” but these principles were not binding, and Bradley had considerable discretion.

“I was free in a tactical sense to command however I wished. I chose to pattern my administration somewhat on the model set by Sir Harold Alexander, who had commanded the 15th Army Group in Tunisia and the 18th Army Group in Sicily and Italy,” he reflected. “I would issue broad ‘missions’ but at the same time I would watch the situation very closely and suggest orders or modification as I thought required, even to the movement of specific divisions. In sum, I would exercise very closest control over Hodges and Patton.”

During the turn from Brittany, Bradley harkened to the spirit of the American military tradition and his own tactical desires by selectively violating the former (going over the head of his superiors when necessary) to achieve the latter.

The 12th Army Group, after one week in battle, was situated around a small chateau on a large farm. Once his new headquarters was settled, Bradley’s routine quickly resumed with small changes from First Army procedures. Operations chief Brig. Gen. Frederick Kibler began the 0830 morning meeting describing operations since the last briefing, and Red O’Hare gave the personnel picture. One week after activation, on August 7, 1944, the Army group had an estimated effective strength of 560,000 soldiers, including 1,400 replacements received in the previous 24 hours.

Bradley had under his command two field armies, six corps, and 21 divisions, including airborne, armored, mechanized, and infantry formations. Since D-Day they had suffered 114,000 cumulative casualties, including 16,000 dead, and taken 77,000 prisoners. Intelligence estimated they had killed or wounded 115,000 German soldiers. After Red, operations officers reviewed the front from left to right, starting with Major Tom Bigland giving the latest plans and appreciations of 21st Army Group. As Montgomery’s principal liaison to Bradley’s headquarters since just before D-Day, Bigland’s report received broad attention. Reports on First and Third Armies followed, presented by liaison officers who by that time had begun to adopt Bigland’s methods honed in Normandy.

The G-2 Daily Intelligence Summary, usually given by General Edwin Sibert, was a central feature of the meeting, describing the current enemy order of battle and recent movements, followed by a report on air operations by the Ninth Air Force liaison and the daily weather report and forecast. Important as a means of orienting the officers of 12th Army Group to common purpose, the daily staff briefing was also a source of vital and interesting information, including timely political, geographic, or military data presented by appropriate staff sections or specialists.

General Bradley asked questions directly, which differed from the British system, where the chief of staff took the lead and conducted the dialogue among the general staff (GS) officers about topics of interest. After the formal meeting, the Ultra officer, Major Alexander Standish, briefed the top officers about the most sensitive intelligence. Operating out of his own van and with “shoot to kill” security measures in place, the 44-year-old Boston stock analyst controlled the raw Ultra intelligence messages that arrived each day and could not be taken outside the van, no matter the circumstances.

“The messages were picked up by powerful receivers in England, decoded and translated, put into a British code and re-broadcast to a British unit attached to Eagle TAC which again decoded them and delivered them to me,” Standish explained. “It was my duty and that of my staff, consisting of five or six non-commissioned officers, to winnow the wheat from the chaff, maintain a complete ‘Situation Map’ and brief General Bradley daily utilizing the ordinary intelligence provided by the armies’ G-2s observation and prisoner of war interrogations as well as the Ultra intelligence.”

Originally, the commanding general’s briefing was held twice daily and then reduced to one lasting for half an hour each morning. The head of G-3 Operations Branch, Colonel Gilman C. “Gim” Mudgett, one of Bradley’s West Point math students and a protégé of Chief of Staff Lev Allen, was in charge of the liaisons. An expert cavalryman and expert in “advanced equitation,” Gim held a liaison officers briefing at 0810 and also briefed General Bradley each evening at 2115 in his quarters. Although Bigland had a major impact at First Army in changing the way American liaisons operated, he credits Gim Mudgett for the adoption of the spirit of the British liaison system and the growing confidence of his American colleagues about their role and importance.

At any time, the liaison officers were authorized to convey appropriate information to Gim, and Bradley could call on them for briefings or special assignments. The rules governing sensitive Ultra information, however, applied to the group commander no less than any GI, and those who knew the secret also knew the consequences of sloppiness.

Attendance at the morning meeting was strictly controlled, and only the general officers and chiefs of general and special staff sections were cleared to attend because of tight space in the trailer van. Frequent high-ranking visitors, generals, and politicians made the space problem worse. Liaison officers had low attendance priority, except for Major Bigland who had a seat in the trailer during the whole war as Monty’s representative. When Ike took over the ground war on September 1, Bradley requested that Bigland move up to Eagle TAC (12th Army Group forward headquarters) as well, evidence of the position of trust and respect Bigland held at Eagle TAC. By that time his daily and periodic reports at both Army group headquarters had a wide, if unofficial, circulation, and he constantly met officers complimentary of his work, stressing not only the information about the British, but how much insight he provided into their own command and forces.

As Major Bigland traveled the battlefield and settled into his new job, he gained even more appreciation for the Americans’ unmatched ability to adapt and innovate, the practical effects of their often parodied “can do” attitude. The invention of the Rhino was only one example.

“In Normandy and after,” he recalled, “I saw many things done which I said at Fort Leavenworth were impossible. It began to dawn on me that the Americans were at the same stage of war in 1944 where we had been in 1941-2, but that, while we were then fighting a superior German, better prepared for war and with superior equipment, we were now superior in men and equipment, above all in the air. We had asked a lot of our troops in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy and those that had survived tended to take more precautions and to move more slowly.”

When Bigland returned from his alternate day visit to 21 TAC on August 7, he took some soap “to have a good wash in a muddy, four-foot-deep stream which was somewhat smelly probably owing to dead cows upstream” and went to mark up the map in the operations tent. Since the morning briefing new red lines now pierced General Leland Hobbs’s 30th Infantry Division front in several locations. Bradley asked Bigland to join a conference to share the latest British picture as he was already thinking about catching the exposed Germans and wanted to get a good sense of Montgomery’s thinking and plans.

Instead of pulling back, as any reasonable commander would do, the enemy had mounted a serious counterattack with five panzer divisions (most of their remaining armor in Normandy), including the crack 116th Panzer and 2nd Panzer, as well three divisions of the I SS Panzer Corps.

In the aftermath of the successful Allied breakout, rather than the withdrawal dictated by military reality and advised by his own general staff, Hitler had ordered a counterattack with the strong mobile forces that he had held back in Normandy.

“The Germans were faced with a serious problem,” wrote Bradley. “Should they withdraw their forces behind the Seine River, a good defensive position, or should they counterattack and try to reestablish the line that had confined us in the beachhead. I am sure the trained German generals would have preferred the former, but Hitler made the big decisions himself.” That was a solid insight that Bradley and every other senior commander forgot by mid-December with terrible consequences.

Mortain, a small village perched on a rocky ledge overlooking the Cance River and dominated by a beautiful 13th-century church, was the Germans’ first objective. About 20 miles east of the Normandy coast and 15 miles south of Vire, it was the key to Avranches, a bottleneck along the main coastal supply route for Patton’s men fanning out to the south, southwest, and southeast, and highly exposed to isolation. Taking Avranches would split the American First and Third Armies, effectively cutting the latter off from its supply and dealing it a crippling blow before it even got into the fight.

Only weeks before, on July 20, 1944, Hitler had barely escaped assassination by a bomb at his Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia, and in a rare expression of personal political opinion, Bradley said what that would mean. “By this time the Germans generals realized that they had no chance of winning the war and ending it would save a lot of grief and many lives. But Hitler had no reason to quit as it would mean his end, so I think the Allies made a mistake in announcing that they would accept nothing short of unconditional surrender as it made it more difficult for the Germans to give up. We could have agreed among ourselves on such conditions without announcing them.”

That may not have been solely a political judgment, as every experienced hunter knows that a cornered animal is more dangerous than one maneuvered by careful prodding to its destruction.

Observing Bradley during his first big battle commanding an Army group, Bigland’s respect for the man grew. “I was most impressed by Bradley’s decision to essentially ignore the German attack and to rely on air to block it, if necessary, which was against the advice of his staff.” It was one of two times during the war when Bigland, drawing on his encyclopedic knowledge of units, deployments, supply situation, and plans, felt he was truly able to predict the outcome of American battles when asked by friends at 21 TAC. He knew that VII Corps, its veteran infantry divisions dug in with armor support close by and backed by air support, was in a good position to halt the counterattack quickly.

Bradley calculated that good weather would allow tactical air support to provide the margin of strength to halt the counterattack. Well-sited artillery batteries with good forward observers in position proved decisive. On the morning of the German attack, a combat command of the 3rd Armored and 30th Infantry Divisions lay directly in the path of the German juggernaut. The battle was costly, especially among the armored infantry. Losses in the 36th Armored Infantry Regiment leadership were ghastly. On a single day the regimental commander, two battalion commanders, two acting battalion commanders, five company commanders, six platoon leaders, two first sergeants, and at least four platoon sergeants were killed or wounded. The regimental surgeon earned a Silver Star dragging a wounded man from a burning halftrack.

Terrain also favored the defenders. Hill 317 was held by a battalion of the 30th Infantry and had a commanding view for miles in every direction. Hodges assured Bradley that Leland Hobbs would hold. Bradley knew Hobbs well, ever since their days as friends and teammates on the famed West Point baseball teams of 1914 and 1915. Every man on those teams became a general officer, including several, like Hobbs, who served under Bradley in World War II. Opinions differ about the value of Ultra in tracking the German panzers, but the defenders were ready, and so was Bradley.

“I saw a great opportunity forming,” Bradley remembered. “If we could contain the counterattack, and if the enemy did not withdraw soon, there was a chance to get enough force behind him to surround and destroy his army.”

When the Germans struck, intending to restore a stable front and cut off U.S. forces moving toward Brittany, they offered the Allies an opportunity for encirclement, every commander’s dream. As soon as weathermen reported clear skies, the IX Tactical Air went to work, inflicting terrific losses on the Germans in men and equipment. Within a few days, in spite of the initial penetration of about five miles, the Germans were halted and badly cut up. The surrounded 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment on Hill 317 broke up the enemy attack and at terrible cost fought one of the great small unit actions of World War II.

Bradley was confident the Germans had blundered in “a historic mistake” that would decide the second battle of France. On the next day, August 8, during a visit by Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Bradley showed the secretary the situation map, confiding, “This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We are about to destroy an entire hostile army.” Morgenthau looked even more surprised when Bradley said he only hoped “the other fellow” would continue his attack for another 48 hours to give his men enough time to get in position to start the encirclement.

The stage was set for the next great challenge, the Second Battle of France.

Author Steve Ossad has written a biography of General Omar Bradley, and publication through the University of Missouri Press is forthcoming. He resides in New York City.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments