When most Americans think of Theodore Roosevelt, they conjure the image of the hard-charging Rough Rider at San Juan Hill, the western cowboy in six guns and chaps, the big game hunter in Africa, or the pulpit-pounding orator promising voters to “speak softly, but carry a big stick.”

Only devoted history buffs know that Roosevelt was also the first American to win the Nobel Peace Prize—or any other Nobel Prize, for that matter. It was perhaps the most surprising and unlikely achievement of his crowded, tumultuous life. And unlike most of his triumphs—and tragedies, too—it was played out entirely behind the scenes, away from the glare of spotlights and the huzzahs of adoring crowds.

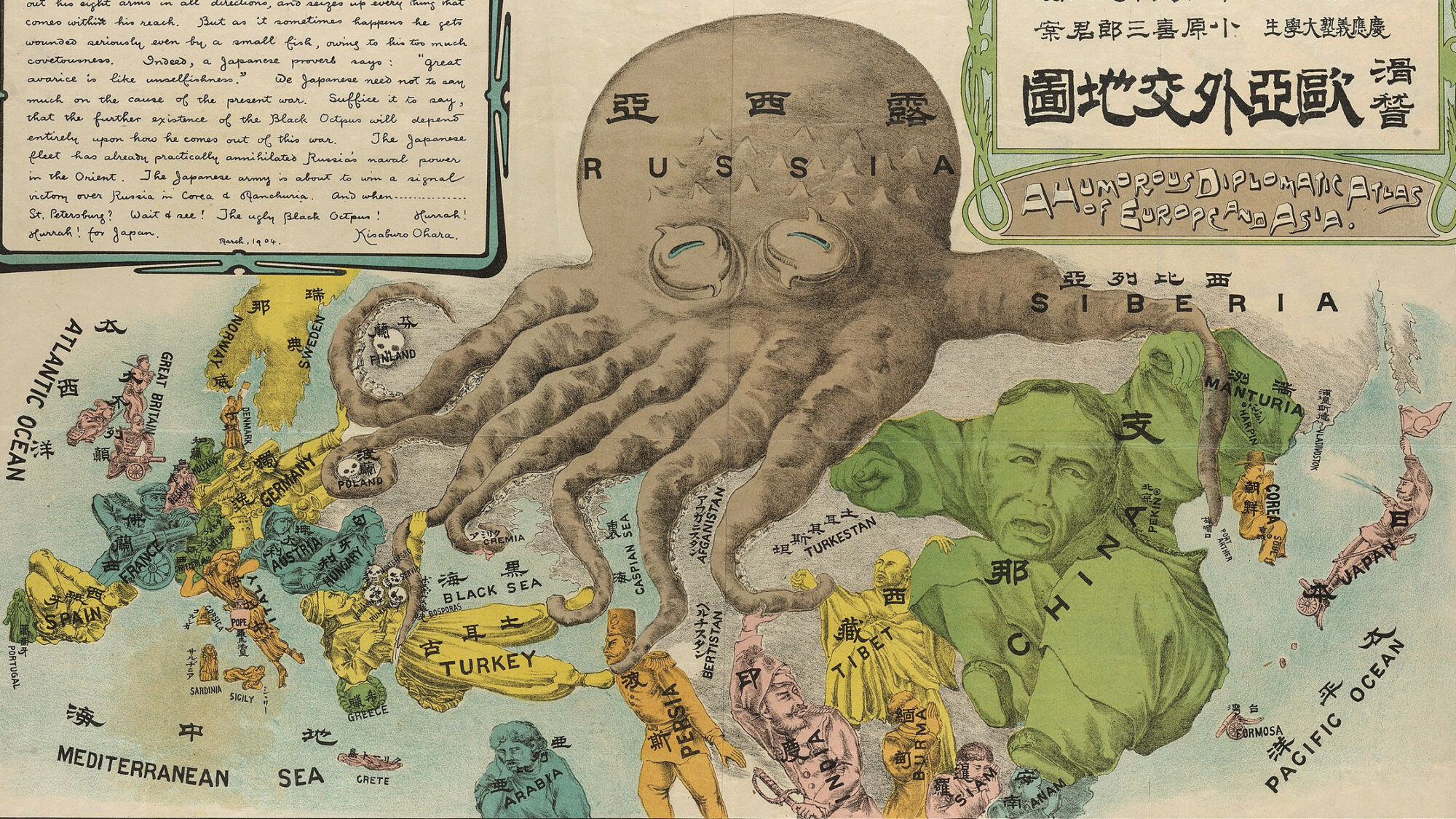

Roosevelt’s inauguration as president in 1905 had scarcely concluded when he found himself embroiled in subtle and sensitive diplomacy on the international stage. The remarkably brutal war between Russia and Japan for hegemony in China had begun 13 months earlier with a Japanese sneak attack—shades of Pearl Harbor—on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur. Subsequent Japanese victories on land and sea, most prominently at the Battles of Mukden and Tsushima Strait, had severely crippled the much larger European nation, but had stretched Japanese resources to the breaking point as well.

Both nations were looking for a face-saving way to end the war. Enter Roosevelt. Japanese envoys in Washington gingerly approached the president in the summer of 1905 and asked him to arbitrate a peace settlement. Like many western leaders, Roosevelt had secretly enjoyed seeing the Russian Bear humbled and humiliated by tiny Japan. “I was thoroughly well pleased with the Japanese victory,” Roosevelt wrote confidentially to his son Kermit. “Japan is playing our game.” But he was beginning to worry that Japan was playing the game a little too well. It was not in American national interests for Japan to swarm over the entire Chinese mainland or extend her sphere of interest across Asia as far as the Philippines. Enough was enough.

Roosevelt began an intricate pas de trois with the warring countries, preserving at least the semblance of neutrality by convincing red-faced Russian diplomats that the peace conference was entirely his own idea. He invited both countries to send representatives to Portsmouth Naval Station in New Hampshire (Washington, D.C., was too hellishly hot in pre-air conditioned times). That August, the two sides sat down on specially imported mahogany furniture to bring an end to the mutually devastating war.

After hosting a welcoming lunch for negotiators aboard the presidential yacht Mayflower, Roosevelt stayed carefully out of the picture, summering with his family at Oyster Bay, New York, but monitoring by telegraph each painful and contentious step in the peace process. As usual, the Russians were the main stumbling block. “No human beings, black, yellow or white could be quite as untruthful, as insincere, as arrogant—in short, as untrustworthy in every way—as the Russians,” the president fumed. The Japanese, meanwhile, were “a wonderful and civilized people entitled to stand on absolute equality with all the other peoples of the civilized world.”

When negotiations stalled over the question of Russian reparations to Japan, Roosevelt approached Czar Nicholas II of Russia and the Czar’s cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, urging them that it was in Russia’s best interests to end the war—at any cost. At the same time, he went through back channels to Japan’s mutual ally, Great Britain, to warn the Japanese that “the opinion of the civilized world will not support it continuing the war merely for the purpose of extorting money from Russia.”

In the end, the Japanese blinked, dropping their demands for reparations and agreeing to share control of strategic Sakhalin Island with the Russians. “This is splendid! This is magnificent!” Roosevelt exclaimed upon hearing the news. “It’s a mighty good thing for Russia, and a mighty good thing for Japan. And a mighty good thing for me, too.” The Nobel Prize committee agreed, making Roosevelt the first of four American presidents (and the only Republican) to be awarded the prestigious Peace Prize.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments