By Mason B. Webb

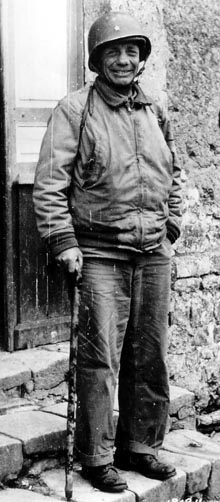

Teddy Roosevelt Junior had enjoyed a distinguished career even before D-Day. He had commanded a battalion in France during the Great War, served as secretary of the Navy from 1921 to 1924, been the governor of Puerto Rico from 1929 to 1932, and been governor-general of the Philippines for a year in the early 1930s. In 1934, he left government service to become chairman of the board at the American Express Company. There was absolutely no reason for him to have been in another war, and yet there he was.

During Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in 1943, he was the assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division, second only to Maj. Gen. Terry Allen. Both he and Allen were beloved by their men—and there was the rub.

Both he and Allen were relieved of command of the 1st Infantry Division at the conclusion of the battle for Sicily by Omar Bradley, who said the relief was necessary, because, Bradley asserted, “Despite their prodigal [sic] talents as combat leaders, neither Terry Allen nor … Roosevelt, the assistant division commander, possessed the instincts of a good disciplinarian. They looked upon discipline as an unwelcome crutch to be used by less able and personable commanders.…

Teddy Roosevelt Junior: “A Brave, Gamy, Undersized Man”

“Had he been assigned a rock-jawed disciplinarian as assistant division commander, Terry could probably have gotten away forever on the personal leadership he showed his troops. But Roosevelt was too much like Terry Allen. A brave, gamy, undersized man who trudged along the front with a walking stick [he had been wounded at the battle of Soissons in 1918 during World War I], Roosevelt helped hold the division together by personal charm.”

Bradley remembered that, after Roosevelt had been relieved as the Big Red One’s assistant division commander, he was assigned to a desk job in Italy but couldn’t stand the boredom. “He wrote to me in England, begging for a job on the invasion,” Bradley said. ‘If you ask me, I’ll swim in with a 105 [howitzer] strapped to my back. Anything at all. Just help me get out of this rats’ nest down here.’”

Bradley gave the request special consideration. He noted, “Because the 4th Division was green to fire, it was difficult to anticipate how it might behave on the assault. If Roosevelt would go in with the leading wave, he could steady it as no other man could. For Ted was immune to fear: he would stroll casually about under fire while troops around him scrambled for cover and he would banter with them and urge them forward.

“He braved death with an indifference that destroyed its terror for thousands upon thousands of younger men. I have never known a braver man, nor a more devoted soldier,” Bradley said.

Roosevelt’s Utah Beach Stroll

Now, on June 6, he walked across Utah Beach as though he was taking a stroll along the beach at his Oyster Bay, Long Island, home, talking to the young soldiers who were under enemy fire for the first time, joking with them, telling them that they weren’t going to win the war by lounging around on the beach.

Later, during the breakout from the beachhead and hedgerows code-named Operation Cobra, Bradley and Eisenhower were trying to decide who should be selected to replace the commander of the 90th Infantry Division. Both Roosevelt and Raymond McLain were up for consideration.

Bradley recalled that he and Ike “had agreed in Sicily that Ted’s easy indifference to discipline would probably limit him to a single star. ‘The men worship Ted,’ I had explained to Ike, ‘but he’s too softhearted to take a division, too much like one of the boys.’”

But Ike decided that Teddy should command the 90th, and Bradley was about to give Roosevelt the good news when he received some very bad news. Roosevelt had died in his sleep of a heart attack on July 12, near Ste. Mère- Église.

As Bradley wrote, “Ted had died as no one could have believed he would—in the quiet of his tent.”

Roosevelt was later awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously, and is buried at the American Military Cemetery above Omaha Beach next to his brother Quentin, an aviator who was killed during World War I. Teddy Roosevelt Junior was just 57 when he died. (Look inside WWII History magazine for more stories about the iconic soldiers who came to define the Second World War.)