By Michael D. Hull

Famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle reported in August 1944, that one of his favorite U.S. Army officers was a regimental colonel who shared Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s philosophy for World War II—simply to kill Germans.

This Regular Army colonel, said Pyle, wore a “new type field jacket that fits him like a sack,” carried a cane, and, like Patton, constantly prodded his commanders to “push hard, not to let up, to keep driving and driving.” Pyle said the officer “is impatient with commanders who lose the main point of the war by getting involved in details.”

In one of his many frontline dispatches, the homespun Hoosier journalist wrote, “Once I was at a battalion command post when we got word that 60 Germans were coming down the road in a counterattack. Everybody got excited. They called the colonel on the field phone, gave him the details, and asked him what to do. He had the solution in a nutshell. He just said, ‘Shoot the sonsabitches,’ and hung up….”

The colonel, Pyle said, “is rather unusual-looking. There is something almost Mongolian about his face. When cleaned up, he could be a Cossack. When tired and dirty, he could be a movie gangster. But, either way, his eyes always twinkle.”

Pyle was referring to Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the oldest son of the 26th American president Theodore Roosevelt (TR), and who had held the rank of colonel when the reporter first met him in Tunisia. A combat veteran of World War I and action in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy, General Roosevelt became one of the heroes of the Normandy invasion and a Medal of Honor recipient. Like his dynamic father, he was virtually fearless, and, like Pyle, he was loved by the soldiers with whom he served.

Despite poor health, “Ted” served as the assistant commander of two hard-fighting divisions and was one of America’s outstanding combat commanders in World War II.

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., was born November 13, 1887, at the family estate in Oyster Bay Cove, New York, when his father was starting his political career. He had three brothers Archibald (Archie), Quentin and Kermit; a sister, Ethel; and half-sister, Alice. Like all of the Roosevelt children, the bespectacled, studious-looking Ted was greatly influenced by his father and strove for his approval.

When TR went to Washington, D.C., as civil service commissioner, Ted often accompanied him to his office. The walks were history lessons. “On the way down,” recalled Ted, “he would talk history to me—not the dry history of dates and charters, but the history where you yourself in your imagination could assume the role of the principal actors…. Long before the European war had broken over the world, Father would discuss with us military training and the necessity for every man being able to take his part.”

Demonstrating a flair for business, young Ted had a brief fling in the steel and carpet fields before venturing into Wall Street, where he amassed a $7 million fortune. Ted married Eleanor Butler Alexander in June 1910, and they had four children—Grace, Theodore III, Cornelius, and Quentin II.

While the American Expeditionary Force was organizing for deployment to France, TR, who had left the White House in 1909 but was still a national figure, wired its commander, General John J. Pershing, asking if his sons could go along as privates. Archie was given a commission with the rank of second lieutenant, while Theodore Jr. was offered the rank of major. Quentin had been accepted into the fledgling Air Service of the Army Signal Corps, and Kermit volunteered to serve with the British Army in Mesopotamia.

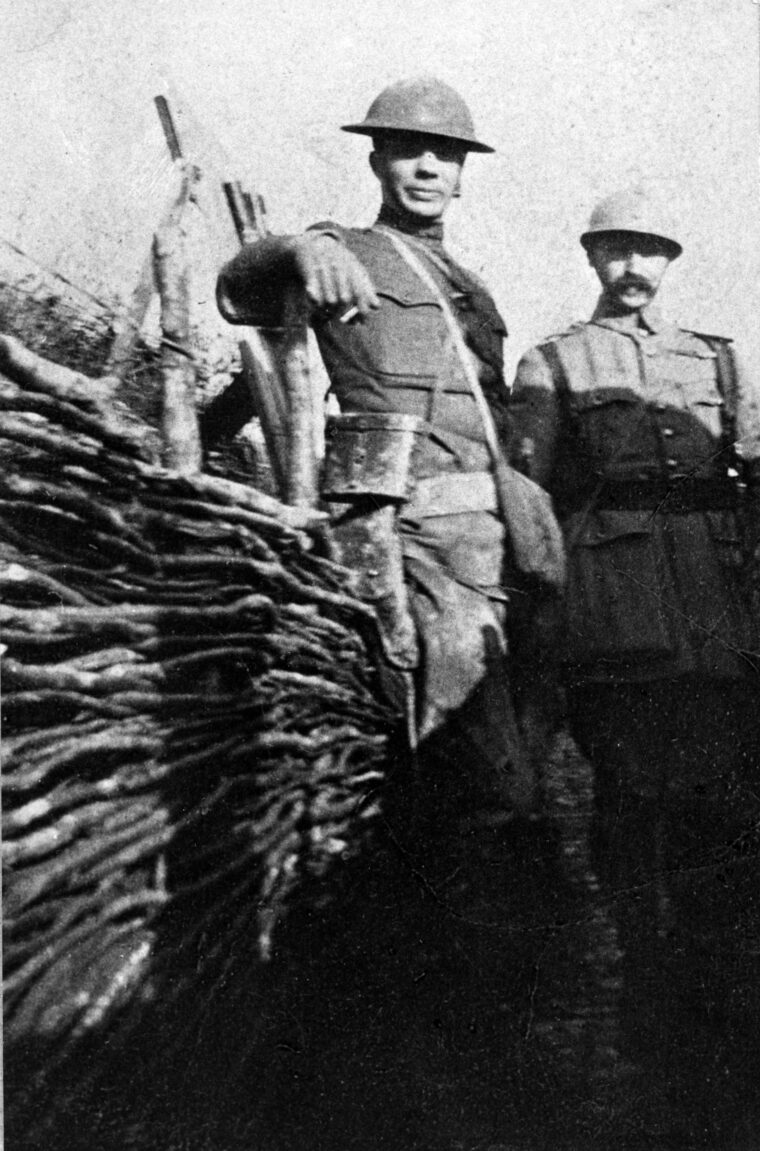

Ted was called up shortly after President Woodrow Wilson declared war and volunteered to be one of the first soldiers to go to France. Small, wiry, and with a bent nose, he sailed in June 1917 with the ragtag, hastily assembled 1st Infantry (Big Red One) Division, then commanded by Major General William L. Sibert. The division disembarked at Bordeaux, and Ted and Archie rode a train to Paris to report to General Pershing, who assigned Archie to the 16th Infantry Regiment. Major Ted joined the 26th Infantry Regiment, billeted in the town of Demange-aux-Eaux, and was given command of a battalion. He soon proved himself a staunch warrior in his father’s mold. He led his battalion across fields in front of the town of Cantigny in May 1918 to plug a gap in the American lines, and took part in the major Meuse-Argonne offensive in August-November 1918.

Theodore Jr. never shied away from danger, telling a fellow officer, “We’re officers aren’t, we? I always thought an officer’s job was to lead his men, not follow them.” Believing that a good officer takes care of his men, Ted purchased combat boots for the entire battalion with his own money.

Ted was gassed and wounded twice at Soissons in the summer of 1918. He went absent without leave from a hospital to rejoin his unit. Meanwhile, his brother, Quentin, had been killed in action that July, an event that devastated TR. Ted eventually was promoted to lieutenant colonel, was given command of the division’s 26th Regiment, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, a Silver Star with oakleaf cluster, the Croix de Guerre, the Legion of Honor, and a Purple Heart.

A few days before TR’s death on January 6, 1919, his daughter-in-law confided to him that her husband was worried about being worthy of his father. “Worthy of me?” answered the former president. “Darling, I’m so very proud of him. He has won high honor, not only for his children, but, like the Chinese, he has ennobled his ancestors. I walk with my head higher because of him.”

Before the doughboys returned home at the end of World War I, a number of AEF officers were asked for ideas on how to improve troop morale. Colonel Roosevelt proposed an organization of veterans which led, at a caucus of of about 1,000 officers and enlisted men, to the founding of the American Legion in Paris in March 1919. Congress granted it a national charter that September. When the Legion met in New York City, Roosevelt was nominated as its first national commander. But he refused because he feared that his acceptance would be viewed as a political move.

Ted left the service and for a political career. Elected to the New York State Assembly in 1919, he had the dash and style of his father in Albany. Grinning, waving a crumpled hat, and shouting “Bully,” he participated in every national campaign except when he served later as governor-general of the Philippines. When Ohio publisher Warren G. Harding was elected president in 1921, Ted was appointed assistant secretary of the Navy, a post that had also been held by his father and his cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Meanwhile, Ted resumed Army reserve service. He attended summer camps, infantry officers’ courses at the Command and General Staff College, and promoted defense readiness.

In September 1929, President Herbert Hoover appointed Ted as governor of Puerto Rico where he worked hard to ease the widespread poverty and became a popular figure. Hoover was so impressed that he named Ted governor-general of the Philippines in 1932.

His colonial career ended when his cousin successfully challenged Hoover for the presidency in 1932. Ted regarded Franklin Roosevelt as “such poor stuff,” and thought it improbable that he would be elected. When this happened, Ted wryly described himself as “fifth cousin about to be removed.”

As war in Europe loomed late in the 1930s, Ted Roosevelt saw a second and probably final chance for challenge and glory on the battlefield. He was now in his 50s, with a fibrillating heart and troublesome arthritis linked to his World War I wounds that forced him to use a cane.

After completing a military refresher course in 1940, Ted petitioned General George C. Marshall, the Army chief of staff, to take him out of the Reserve and return him to active duty. In April 1941, with the rank of colonel, he was given command of his old unit, the 26th Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division. After a short time, he was promoted to brigadier general.

After taking part in the Carolina maneuvers of late 1941, the Big Red One trained in North Carolina, Massachusetts, Florida, Georgia, and Pennsylvania, and left New York for the European Theater of Operations on August 1, 1942. Crammed into the converted liner Queen Mary, the division arrived in Scotland on August 7. It was then sent by rail to England, where it underwent advanced training. Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, a veteran of the 1916 Mexico punitive expedition and the 1918 St.-Mihiel offensive, had taken command of the division in June 1942. Ted Roosevelt was his assistant commander.

Less than three months after its arrival in Britain, the 1st Infantry Division was bound for the western Mediterranean Sea to take part in the first great Allied invasion of the war, the three-pronged Operation Torch. Three convoys —the Western Task Force under Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr., the Central Task Force under Major General Lloyd R. Fredendall, and the Eastern Task Force under Major General Charles W. Ryder—were to converge, land in Morocco and Algeria on November 8, overcome Vichy French opposition, and eventually link up with General Bernard L. Montgomery’s Eighth Army advancing across North Africa from the east. The Big Red One was the spearhead of the Central Task Force, and its objective was the Algerian port of Oran.

Ted Roosevelt was in high spirits as the Central Task Force steamed toward North Africa late in October 1942. Aboard the converted liner Monarch of Bermuda, he entertained staff officers by reciting from memory long passages of his favorite poet, Rudyard Kipling, after they had challenged him with a succession of first lines. On October 26, he wrote to his wife, “Cleared for strange ports—that’s what we are. Here I am off again on the great adventure.” Using his father’s language, he told her that he had done his best and that his fate was now “at the knees of the gods.”

Early on November 8, the 1st Infantry Division lay in darkened transports off Algeria in the Gulf of Arzew. Tensely, the soldiers—most of them untried—oiled their weapons, adjusted equipment, and hoped that they could live up to the reputation established by the division’s old-timers. Men of the 16th and 18th Regiments went ashore east of Oran, and Roosevelt led the 26th Regiment across the beach at Les Andalouses. Fredendall’s task force did well in its initial combat operations against sporadic Vichy French and German resistance, swiftly taking the cities of Oran, Arzew, and St.-Cloud.

After the heights above Oran had been captured, the city still held out, and shelling seemed to be the only recourse. Instead, General Roosevelt told his regiment to hold its fire while he and an aide mounted a half-track. “If I’m not back in two hours,” Ted told his men, “give it all you’ve got.” Flying a dirty undershirt as a flag of truce, the half-track roared off into the city. Eventually, the enemy gunners capitulated and considerable destruction was avoided.

The cheered widly as Roosevelt’s regiment entered Oran on November 10 and they wen ton to clear the Ouseltia Valley in January 1943, and on to positions at Kasserine Pass the following month. The 26th Regiment saw plenty of action against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Korps. Ted’s men helped to check two strong German counterattacks in March 1943, cleared Hill 575, and reached Djebel el Anz against strong resistance that April. The Big Red One was actively engaged in Tunisia until May 9, 1943.

Ted’s reputation grew as a hard-fighting frontline general. His leadership early in 1943 was cited by General Alphonse Juin, gallant leader of the Free French forces in North Africa: “As commander of a Franco-American detachment on the Ouseltia plain in the region of Pichon, in the face of a very aggressive enemy, he showed the finest qualities of decision and determination in the defense of his sector. Showing complete contempt for personal danger, he never ceased during the period of Jan. 28-Feb. 21, visiting troops in the front lines, making vital decisions on the spot, winning the esteem and admiration of the units under his command, and developing throughout his detachment the finest fraternity of arms.”

Ted Roosevelt and his immediate superior, the hard-drinking “Terrible Terry” Allen, led the Big Red One in an unorthodox manner. Devoted to their men, they strove from the foxhole level to build the division into a first-rate fighting organization. Allen fretted over shortages of dry socks at the front, and Roosevelt pestered mess sergeants to make sure they had enough baking powder. A soldier, Pfc. Louis Newman, recalled standing near the general one day as weary, sweating GIs were returning to camp after a long march. Their officers were riding in jeeps, but Ted ordered them out of the vehicles. Gesturing toward the enlisted men, he said, “They walk, you walk.”

The two generals, neither of them disciplinarians, felt comfortable among the lowest ranks, placed little value on spit-and-polish, and were seldom seen in regulation uniforms. Ted usually wore a knit cap because he hated the heavy Army helmets. Ted’s aide, Lieutenant Marcus O. Stevenson, reported later, “He was the most disreputable-looking general I have ever met…He looked like the most beat-up GI you ever saw.”

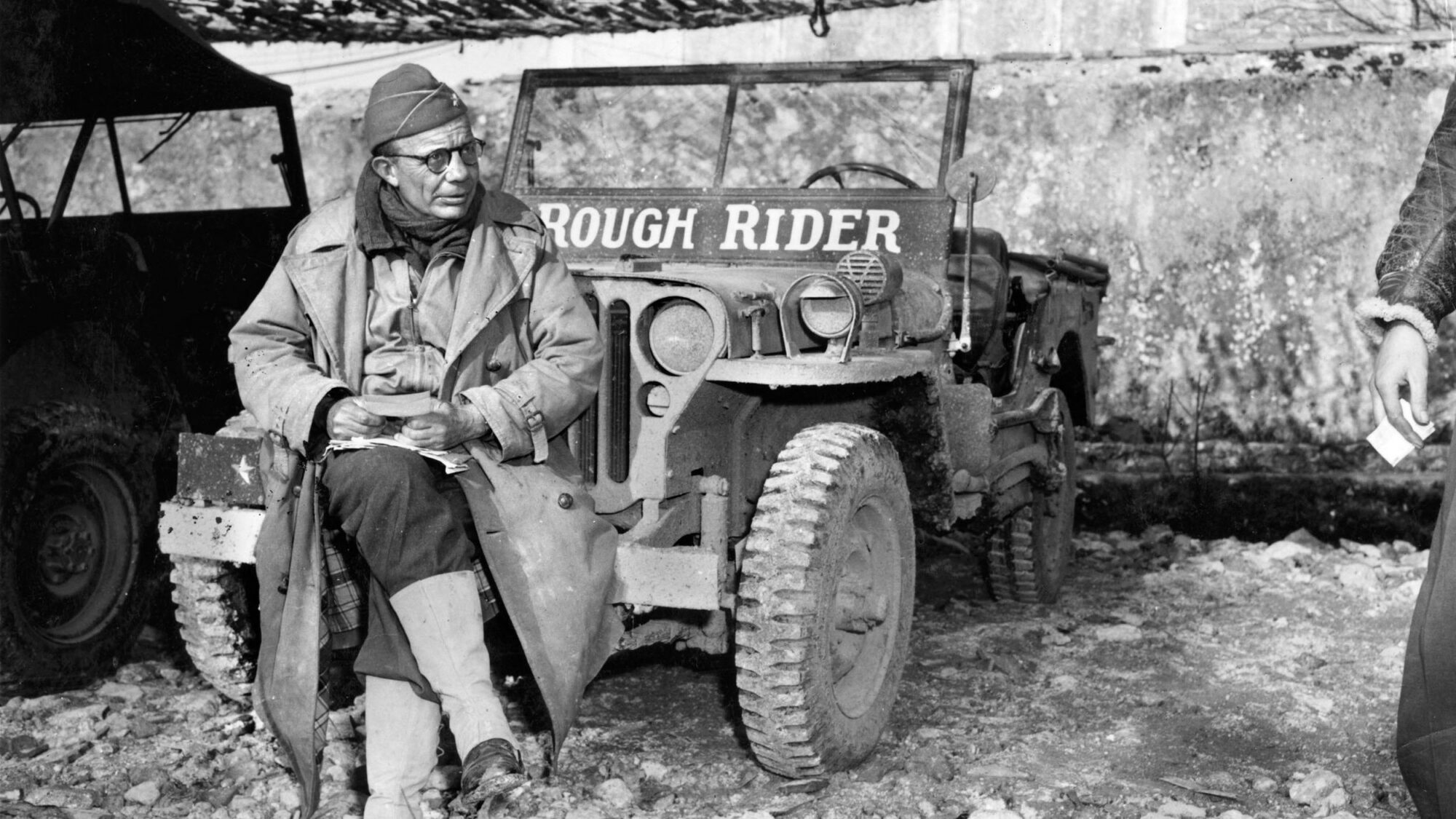

Ted told an aide on March 1, 1943, that he had just changed clothes for the first time since January 14. Driving a jeep named “Rough Rider” in honor of his father around the division’s foxholes, mortar pits, and artillery batteries, he shuffled among the tents to encourage and joke with the GIs. “Once we’ve licked the Boche,” he would say in his bullfrog voice, “we’ll go back to Oran and beat up every MP in town.” When the men lined up for delousing after scrubbing their filthy uniforms with gasoline, he helped to pass out decorations for gallantry before speeding off to another bivouac.

“I’ve always thought that it was nonsense to say Americans don’t like medals,” he wrote to his wife, Eleanor, then serving with the American Red Cross in Salisbury, Wiltshire. “I knew I liked them. I wanted to get them, put them on, and walk up and down in front of you and say, ‘Look what a hell of a fellow you’ve married.’” He was usually light-hearted, but he was well aware that the Allies were in a fight to the death for the duration. “I think this is a five-year war,” he wrote prophetically to his wife. “It won’t be over until another winter has passed, until we are firmly on the continent, and until Germany is faced with still another winter…Now we know too much…We know there’ll be troubles of every sort.”

Few World War II generals were as close to their men as were Terry Allen and Ted Roosevelt of the Big Red One. Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, who took over command of the U.S. II Corps from Patton in April 1943, reported standing with Roosevelt one night in Tunisia while a blacked-out convoy of the 1st Division moved slowly along a road. Ted turned to Bradley in the darkness and said, “Brad, I’ll bet that I’ve talked to every man in this division. They’d know my voice whether they could see me or not. Listen!” Ted shouted hoarsely to a passing truck, “Hey, what outfit is that?” A hearty voice replied, “Company C of the 18th Infantry, General Roosevelt.”

After more than five months of bitter battles and some disastrous setbacks, the British and American forces boxed their depleted, starving German and Italian foes into a corner in Tunisia in late April 1943. The enemy surrendered on May 1, and the struggle for North Africa was over. Having suffered heavy casualties, the 1st Division was pulled off the line and trucked back to an area near Oran for rest and reinforcements. But the weary Big Red One had a chip on its shoulder and was about to tarnish its reputation. Still wearing woolen uniforms as the weather turned hot and denied entry to Services of Supply clubs and installations, the division’s soldiers decided to “liberate” Oran a second time. While other Allied units paraded majestically to the accompaniment of British bagpipe bands in Tunis, General Allen’s soldiers ran amok, brawling, looting wine stores, and outraging public officials.

Patton, the spit-and-polish taskmaster who had striven to shore up flagging American discipline and fighting spirit early in the North African campaign, was not amused, and retribution was imminent for the Big Red One. Meanwhile, the division next took part in Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Allen’s men landed at Gela on July 10, 1943, repelled a German armored attack the next day, pushed inland, captured three towns, seized the Salso River crossings, and blunted a German counterattack. They fought a series of sharp engagements in rugged terrain and reached the town of Troina in central Sicily on August 1.

The Big Red One launched an all-out attack on the town on August 4, but it failed. The town was not taken until the night of August 5-6, when the German defenders began slipping out of Troina and the surrounding mountains. Allen’s men marched into the shattered town on the morning of August 6 to find the enemy gone. It had been a costly struggle, with some of the division’s rifle companies whittled from 193 to 65 men. The action at Troina also claimed two more casualties—Generals Allen and Roosevelt.

While the battle was still raging, a high command message was sent to Allen that was not supposed to reach him until afterward: he and his assistant commander were to be relieved. Patton, regarding both officers as unsoldierly though gallant, had sent derogatory reports to Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Mediterranean theater commander, who had viewed Allen as exhausted in May 1943. He approved the request for their relief, and Bradley assumed full responsibility for the action. Bradley considered Allen too much of an individualist, Ted too close to his men, and the division too full of pride and self-pity and unable to function willingly as part of a larger group. Said Bradley, “Roosevelt had to go with Allen for he, too, had sinned by loving the division too much.”

As the Big Red One left Sicily in October 1943 and landed in England to train in Dorset and Devon for the upcoming Allied invasion of northern France, Allen was given command of the 104th Infantry Division, which would later distinguish itself in Normandy and the Rhineland. Roosevelt, meanwhile, was appointed in December 1943 as the chief U.S. liaison officer between General Mark W. Clark’s Fifth Army and the French Expeditionary Corps under General Juin.

Ted distinguished himself when detached on a special mission to Sardinia, where an Italian parachute division was holding out and refusing to surrender to the Allies. Unarmed, Ted went from unit to unit convincing the “good, plug-ugly roughneck” Italians to help drive the Germans out of their homeland. Lt. Col. Serge Obolensky of the Office of Strategic Services said of General Roosevelt, “By the sheer force and charm of his personality, and an exhibition of the coolest gallantry, he won the wavering troops to a wild personal ovation.” Six of the Italian paratroops had been assigned to kill Ted and Obolensky. Shortly before Christmas 1943, Ted accompanied French troops into the line during the bitter Monte Cassino campaign in Italy. He was at the front every day with General Juin, whom he described as a “front-fighting general.” Juin later wrote to Ted, “There is no one in the (French) Corps from the lowliest private to the most bestarred general who does not know and love you.”

After Cassino, Ted badgered Eisenhower for a combat command. He fidgeted among the brass in the Mediterranean theater, yearning to get back into the shooting war. When he could stand it no longer, he wrote to General Bradley, then commander of the U.S. First Army, begging for a role in the planned invasion of northern France, Operation Overlord. “If you ask me, I’ll swim in with a 105 (howitzer) strapped to my back,” said Ted. “Anything at all. Just help me get out of this rats’ nest down here.”

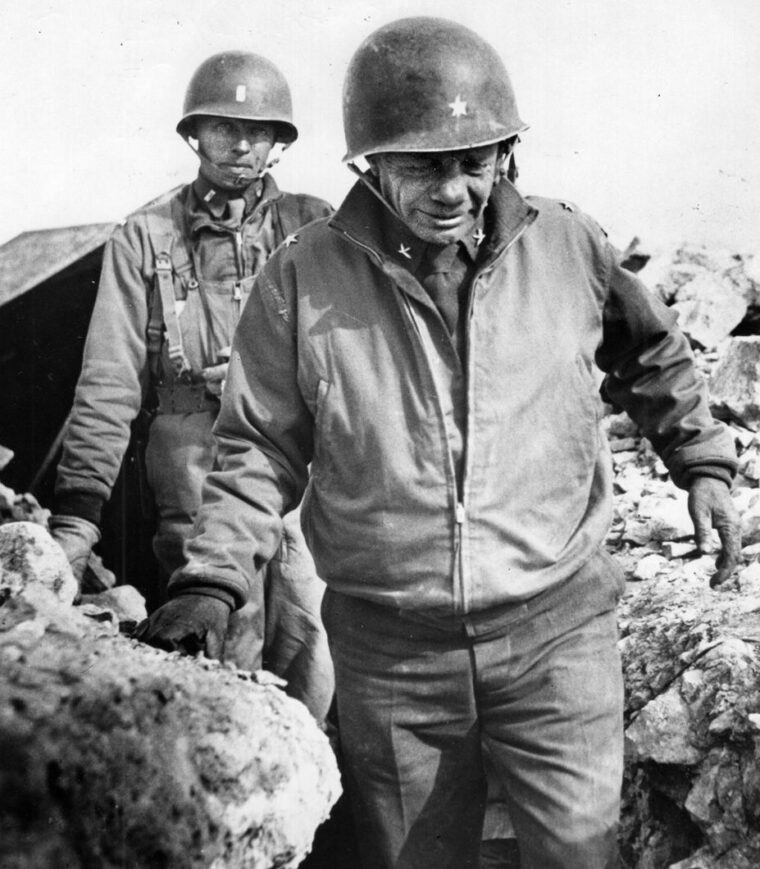

The game little warrior got his way. He was ordered to England in February 1944 and assigned as assistant commander of the untried 4th Infantry Division under Major General Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton. Activated in June 1940 and trained in the South, the division had arrived in England only in January 1944. “Because the 4th Division was green to fire, it was difficult to anticipate how it might act on the assault,” Bradley reported later. “If Roosevelt could go in with the leading wave, he could steady it as no other man could…Ted was immune to fear.” Bradley warned him in a letter, “You’ll probably get killed on the job.”

Ted never replied to him. He broke out of a hospital in Italy where he had been undergoing treatment for pneumonia and reported to Bradley in London a few days later with a raging fever. He was eager to fight again, but Ted had more convincing to do. General Barton voiced serious misgivings about an ailing, 57-year-old general joining the assault wave at Normandy. Barton denied several verbal requests from Ted, but the Big Red One veteran of two wars persisted.

He dashed off an eloquent written petition to the 4th Division commander: “The force and skill with which the first elements hit the beach and proceed may determine the ultimate success of the operation …With troops engaged for the first time, the behavior pattern of all is apt to be set by those first engagements…I believe I can contribute materially on all of the above by going in with the assault companies. Furthermore, I personally know both officers and men of these advance units and believe that it will steady them to know that I am with them…. They’ll figure that if a general is going in, it can’t be that rough. I would love to do this.” Barton reluctantly agreed, but, like Bradley, did not expect Ted to survive.

At a staff conference a few days before the invasion, General Bradley told those present that they would have ringside seats at the greatest fight in history. Ted turned to the officer beside him and whispered, “Ringside, hell! We’ll be in the arena!” He was paraphrasing one of his father’s favorite expressions.

The gray, blustery morning of Tuesday, June 6, 1944, came, and 5,000 assorted Allied ships stood off the Normandy coast for the greatest invasion in history and the long-awaited liberation of German-occupied Northwest Europe. Landing craft bucked through the choppy English Channel carrying British, American, and Canadian infantry divisions to five assigned beaches code named Utah, Omaha, Sword, Gold, and Juno. Carrying his cane and a .45-caliber Colt automatic pistol, Brigadier General Roosevelt was to land with E Company of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, and elements of the 70th Tank Battalion. He was in high spirits—the only general and the oldest man to land at Normandy in the first wave.

While waiting for the launch of the first wave, Ted jotted a sober letter to his beloved Eleanor: “We are starting on the great venture of the war, and by the time you get this, for better or for worse, it will be history…We’ve had a grand life and I hope there’ll be more…We’ve known joy and sorrow, triumph and disaster, all that goes to fill the pattern of human existence. Our children are grown and our grandchildren are here. We have been very happy. I pray we may be together again.”

E Company was the first unit to hit Utah Beach, and Ted was the first soldier off his Higgins boat. As he and the other men scrambled through the surf for cover under German beach obstacles, Ted was told that the landing craft had drifted more than a mile south of the objective, and the 4th Division’s first wave was a mile off course. This was fortunate for E Company because the only opposition was small-arms fire from enemy trenches in a sand dune behind a four-foot concrete seawall.

Wary of snipers, Ted scouted for causeways behind the beach for the division’s push inland. He then consulted with battalion leaders and the commanding officer of the 8th Regiment, Colonel James Van Fleet. “Van,” Ted exclaimed, “we’re not where we’re supposed to be.” Roosevelt then became a D-Day legend for saying, “We’ll start the war from right here!” Van Fleet, who would command the U.S. Eighth Army in the Korean War, disputed this later in an unpublished memoir. “I made the decision,” he wrote. “Go straight inland.”

Throughout that “longest day,” Ted was an inspiration to all, prowling around Utah Beach with his cane and infectious grin, calmly ignoring enemy fire. While grimacing from the pain in his leg, he rallied the men of the 4th Division to go forward and not “turn into targets.” Ted recited poetry and told stories of his father to steady the nerves of scared, wet young soldiers who had never been in action, directed regiments to their changed objectives, and helped to untangle traffic jams of armor and trucks all struggling to move inland. He led a group of men in a charge over a seawall, established them inland, and then returned to the beach to orchestrate more incoming men and materiel. He was a beacon on Utah Beach for several hours.

When General Barton came ashore, he met Ted near the beach. “I loved Ted,” he said later. “When I finally agreed to his landing with the first wave, I felt sure he would be killed. When I had bade him goodbye, I never expected to see him alive. You can imagine then the emotion with which I greeted him when he came out to meet me. He was bursting with information.”

D-Day was a success for the 4th Division. In 15 hours that day, it landed more than 20,000 men and 1,700 vehicles and rolled swiftly inland. On the second day, Utah Beach received 10,735 men, 1,469 vehicles, and just over 800 tons of supplies. Ted Roosevelt’s inspiring leadership had played a major role in that success.

A few days later, Ted was delighted to see his son, Quentin Roosevelt II, 24, in the camp. He had been worried about Quentin, a lieutenant in the 1st Infantry Division, which had been pinned down and mauled on D-Day. Quentin had been wounded at Kasserine Pass and been awarded a Silver Star and the Croix de Guerre at Ouseltia. They were the only father-and-son team to participate in the Normandy invasion.

Late that June, the 4th Division assaulted the strategic port of Cherbourg, where Ted served briefly as military governor. He set up his headquarters in a cellar lit by a single oil lamp, helped to restore order to the ravaged city, and then pushed on with his troops. But Ted’s health was catching up with him. His heart condition was serious, and he knew it. He kept it secret from his wife and avoided doctors at all costs. On July 11, 1944, Ted spent a day at the front lines with his men and then went back to his “little home,” a captured German truck, to rest. Late that evening, after a happy two and a half hours with Quentin, he died of a heart attack.

General Bradley had been in the process of promoting Ted to major general with command of the 90th Infantry Division. On July 12, Quentin wrote his mother, “The Lion is dead…To me, he was much more than simply a father, he was an amazing combination of father, brother, friend, and comrade in battle.”

The funeral service was conducted in the official cemetery at Ste. Mere-Eglise, a few miles west of Utah Beach, on Bastille Day, July 14, 1944. An Army band played “The Son of God Goes Forth to War” as artillery rumbled in the distance. The honorary pallbearers were Generals Bradley, Patton, J. Lawton Collins, Clarence Huebner, Barton, and Courtney H. Hodges. Riflemen fired three volleys, and two buglers sounded taps, echo fashion. Quentin reported to his mother that it was “a warrior’s funeral.” A year after Ted’s death, his brother, Quentin, who died in World War I, was reburied next to him in the sprawling Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer, overlooking Omaha Beach.

General Barton recommended that Ted be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions on Utah Beach, but this was upgraded at higher headquarters, and the Medal of Honor was posthumously awarded in September 1944. When President Roosevelt handed the blue ribbon to Ted’s widow, he said, “His father would have been proudest.”

Ted was the second son of a president to earn the nation’s highest honor, after Rutherford B. Hayes’s son, Webb C. Hayes, who earned it in the Philippine Insurrection in 1899. Only two father-and-son duos have been awarded the medal—Arthur and Douglas A. MacArthur, and President Theodore Roosevelt and Ted. TR’s medal was awarded posthumously by President Bill Clinton in January 2001.

General Patton wrote in his diary that Ted Roosevelt was the bravest soldier he ever knew, and General Bradley agreed, “I have never known a braver man nor a more devoted soldier.” Asked several years later to cite the single most heroic action he had seen in combat, Bradley replied, “Ted Roosevelt on Utah Beach.” Ted’s leadership at Utah Beach was recorded in Cornelius Ryan’s best-selling 1959 book, The Longest Day, and he was portrayed by Henry Fonda in Darryl F. Zanuck’s 1962 film epic of the same name.

Excellent article. There are several photos of Gen. Roosevelt that I have not seen before. I am going to Normandy in April, and I am going to look for the spot where the famous last photo of Ted was taken (smiling in the doorway with his cane). This man was a true hero.