By Christopher Miskimon

The Battle of the Bulge is famously known as the largest battle fought by the U.S. Army in World War II. Some 610,000 U.S. troops were involved, and around 81,000 of them became casualties. Like any action of such size and scope, however, the Bulge was really hundreds of smaller actions linked by common purpose. In the Ardennes, many of them were desperate fights, pitting small units against each other as they vied for control of critical towns, villages, bridges, and crossroads.

Many of these small engagements were between armored forces; the Ardennes fighting was the final large-scale tank battle in Western Europe. The last large reserves of armor the Germans possessed were thrown against the Americans in an environment where it was hoped Allied air power would be grounded by weather.

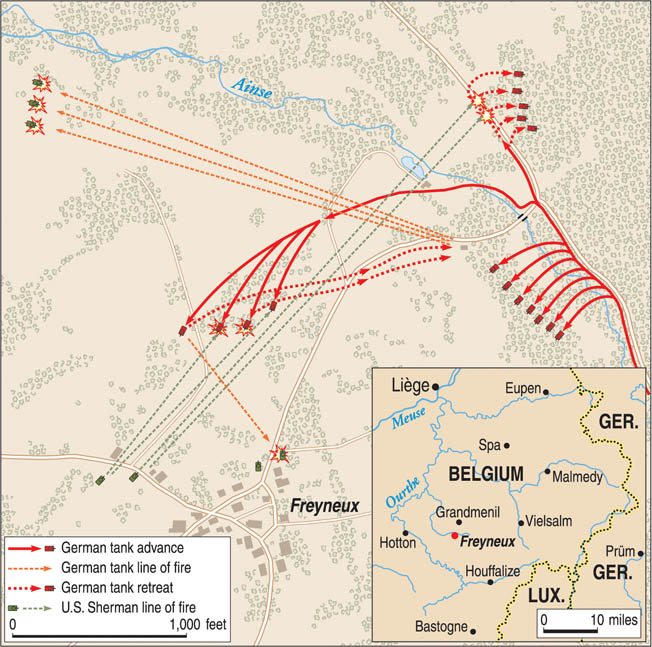

In the chaos of the Ardennes, the various units maneuvered; German formations attacked and sought advantage while American ones defended, biding time while the Allies prepared a response. Two such units, the U.S. 3rd Armored Division and the German 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, fought repeatedly around the small town of Manhay in Belgium, an area of rolling fields and thick forests dotted with tiny villages centuries old.

Across this otherwise picturesque landscape men struggled and died in foxholes and tanks. Amid the thunder of gunfire and the cries of the wounded, American soldiers proved they were a match for the best Nazi Germany could throw at them.

The grand scale of the Bulge notwith- standing, American doggedness and bravery made the difference in dozens of small skirmishes—none more so than one in the tiny hamlet of Freyneux, Belgium, on a cold and snowy Christmas Eve.

The area around Freyneux was the responsibility of the U.S. 3rd Armored Division’s Task Force Kane. This small, combined-arms group was initially assigned the mission of seizing the village of Dochamps southwest of Manhay. Like most American task forces, it was named for its commander, in this case Lt. Col. Matthew Kane.

The unit was composed of a dozen M-4 Sherman medium tanks and five M-5A1 Stuart light tanks from the 32nd Armored Regiment, another four Stuarts from the division’s reconnaissance battalion, and a squad of engineers. For fire support, six M- 7 “Priest” self-propelled 105mm guns were attached from the 54th Armored Field Artillery Battalion. Infantry from other units were to be attached to the task force at various times.

The attack on Dochamps began around 9 PM on December 22. A badly under-strength C Company, 1st Battalion, 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) was sent to attack the village despite the knowledge it was stoutly defended by German troops from Volksgrenadier Regiment 1129. The lieutenant in command of C Company was told to follow railroad tracks running from Freyneux to Dochamps that would guide him to their objective. Several tanks would follow in support.

At first the paratroopers met with success; their scouts seized an enemy machinegun nest and several patrols cleared some woods near the village. But a heavy German counterattack forced the Americans to take cover in a few buildings outside the settlement. They waited there until daybreak on December 23 only to face a concerted attack by another German unit, Volksgrenadier Regiment 1130. A flurry of hand grenades flew through the air from both sides as intense close-quarters combat ensued.

After a short time this assault overwhelmed the exhausted paratroopers, who fell back to another cluster of structures closer to another village named Lamormenil, northeast of Dochamps. There the tanks were able to join them, along with a few towed 3-inch antitank guns from a tank destroyer battalion. The added firepower allowed them to hold off further attacks by the enemy grenadiers.

In nearby Freyneux, Lt. Col. Kane learned of the paratroopers’ failed attack and issued orders for another effort to be made at 2 PM. Third Armored Division headquarters had instructed Kane to make this second attack despite reports of the heavy German defenses in the area; fortunately, the attack was cancelled shortly before it was to jump off. Kane subsequently left to obtain further orders, leaving Major Robert Coughlin in charge of the defenses at Freyneux while the paratroop commander took over at Lamormenil. Task Force Kane had failed to achieve its primary objective, but it was now ensconced in this pair of nearby villages, close to the Germans, who were preparing to resume their counterattacks.

In 1944 Freyneux was a tiny hamlet of some 130 people, a farming community containing about 42 buildings, mostly homes. There were also four general stores, a shoemaker, and a cattle seller—businesses that received most of their income from the farmers who lived in the area. The Catholic Church of St. Isidore sat at the village’s eastern end; there was a small cemetery at the rear of the church inside high stone walls that surrounded the church itself on three sides. Roads from several directions converged at Freyneux, including one that led west to Lamormenil.

The buildings were almost all stout structures made of stone; they sat clustered along the muddy roadways, covered in a layer of glistening snow. A thin screen of trees lay dotted around the village, providing a little concealment. In the distance, thicker forestland sat to the north, northeast, and east.

Northeast of Freyneux the narrow River Aisne, really more of a creek, curved gently through the meadowland. A stone bridge crossed it, connecting the road from Freyneux to another road leading north-south. This road joined the villages of Odeigne and Oster.

Major Robert Coughlin laid out the defenses of Freyneux with a focus on guarding the eastern approaches since the Americans in Lamormenil provided cover to the west; the paratroopers there could provide warning of any threat from that direction.

To cover the road leading southwest back toward Dochamps, he placed two Shermans (commanded by 1st Lt. Elmer Hovland of Luverne, Minnesota) of the 2nd Platoon, D Company, 32nd Armored Regiment. A pair of Stuart tanks from 3rd Platoon, C Company, 83rd Reconnaissance Battalion, was placed alongside the Shermans. Together the four tanks were also to cover another road that led generally off to the southeast.

At the northeast end of Freyneux, Coughlin placed a trio of Shermans from the 3rd Platoon, D Company, 32nd Armored Regiment. One tank belonged to the platoon leader, 1st Lt. Charles Myers. His tank, D-31, an M-4A3 with a long-barreled 76mm gun, was positioned at the very edge of the village just beyond the church. Near the lieutenant’s tanks and just north of the road leading to the stone bridge was the second Sherman, commanded by Sergeant Alvin Beckmann. He placed his tank near a barn and behind a large pile of wood, providing at least some concealment. This tank, D-34, was an older model M-4A1 with the shorter, low-velocity 75mm cannon.

The third Sherman, D-32, was also an M-4A3 (76mm), commanded by Sergeant Reece Graham of West End, North Carolina. His tank was positioned near the road junction and west of the church. Graham was able to place his tank behind a large stone wall that he could just barely shoot over, giving his Sherman cover. Graham had only recently been promoted to tank commander and was short one man from his crew. Even though he commanded the M- 4, he took turns driving it as well.

Another pair of Stuarts set up in support behind these Shermans. While their diminuitive 37mm cannons were almost useless against heavy German armor, the Stuarts could be effective against enemy infantry by using both canister shot from the cannons and their .30-caliber machine guns. These tanks were from the same platoon as their counterparts on the south end of the village. One of these Stuarts was commanded by Sergeant Adolfo Villaneuba of San Antonio, Texas. The young, wiry Villanueba was highly respected among the other soldiers of his platoon.

A small number of dismounted reconnaissance troops, perhaps 45 men, were placed around the village as well, rounding out the American defenses. Major Coughlin also had a few headquarters troops at his command post, but overall the force was long on armor and short on infantry, with few foot soldiers able to protect and screen the tanks.

As dusk settled over Freyneux on December 23, the Americans there prepared for a long, cold night of sentry duty, watching for any sign of enemy troops moving in on them in the darkness. Sitting inside their tanks brought no respite from the frigid night air. Some of the Sherman crews took turns rotating into nearby buildings. Inside they could brew coffee and warm their bodies before braving the chill to stand their watch. A loader in one of the Stuarts, Albert Li Muti, remembered spending an entire night shivering in his tank. “We were half frozen, buttoned up in our tanks,” he said. “We couldn’t turn on our engines, giving our position away. The inside of our tank was like a refrigerator.”

Another tanker, gunner Jerry Nelson, hated nighttime guard duty. In winter the nights were longer. This meant some crewmen would have to take two watches during the night, each two hours long. “It was always very long and lonely in that turret and all we did was think of home,” he recalled.

It could be hard to stay alert as mind-numbing hours passed by. The least noise could cause a green soldier to open fire into the darkness, drawing attention to their position. Most of the men in Freyneux were veterans, however, and no panicked bursts of machine- gun fire interrupted the quiet, inky blackness of the night.

The only noises to be heard were the few preparations still being made. Two 3-inch anti-tank guns from the 643rd Tank Destroyer Battalion arrived in the evening. The crews set up their cannons in some bushes near the church, not far from Alvin Beckmann’s Sherman, D-34. Lieutenant Myers decided to pull his tank, D-31, back from the edge of the village to a better position near the church. He ordered the driver to place the tank at the southeast corner of the church’s wall.

Eventually the dawn began to break, shedding dim light across the fields around Freyneux. Major Coughlin announced an officer’s call and Lieutenant Myers left to attend the meeting, leaving his gunner, Corporal Jim Vance, in command of D-31. The increasing light allowed the young soldier to check the tank’s field of fire. Vance recalled, “The wall around the cemetery was high enough to hide my tank except for the turret. The gun, a 76mm cannon, was able to clear the top of the wall by a few inches.” This placed his tank in a “hull-down” position, making it a more difficult target. Vance and the other tankers around Freyneux continued their vigil, awaiting the return of their leaders to tell them what was planned for the day. It was Christmas Eve, 1944.

A scant few miles away, the Germans of the Das Reich Division spent an equally cold night, shivering in their tanks, preparing for the next day’s assaults, and trying to catch a few hours of much needed sleep. Much of the unit spent December 23 trying to assemble near a vital crossroads well east of Freyneux. Obersturmbannführer (Lt. Col.) Alfred Hargesheimer, commander of the 2nd Company, SS Panzer Regiment 2, arrived with his Panther tanks around 2 PM.

He reported to the regimental command post where his commander, Obersturm- bannführer Rudolph Enseling, took him along to observe the assault on the crossroads. The pair of officers watched from their command half-track while elements of two other units seized the intersection. Afterward they returned to the command post, and Hargesheimer was ordered to prepare his unit for a night attack on Freyneux at 11 PM.

His tanks and others moved out for the pending attack, eventually arriving at a narrow road surrounded by forest. Moving down it, the Panthers veered into a swampy area where a number of them broke through the thin ice and became mired. It took until nearly morning to get them free; some engineers found a better route, and the tanks finally arrived at the village of Odeigne, a few miles east of Freyneux. The attack was rescheduled for the morning of December 24.

A new plan was drawn up to take Freyneux, which was in actuality not the primary target. The main objective was the town of Oster, a few miles northeast. Two companies of Panthers, including Hargesheimer’s, were attached to the SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 3 “Deutsch- land.” This hastily organized Kampfgruppe, or battle group, would take the road to Oster from Odeigne, which ran past Freyneux to the east. Once they arrived at Freyneux, a small force would break off and clear the village, which they believed to be lightly defended. With this potential threat to their flank neutralized, the entire force could then move on to Oster and eventually the larger town of Manhay.

As the panzer crews prepared for their mission, Obersturmbannführer Enseling briefed his officers on what to expect. They pulled out maps of the area and talked about the terrain, which was full of gentle hills, mostly usable roads, and patches of thick forest. It was the best preparation they could do on short notice after the cancellation of the previous night’s attack. While the German leaders could look over their maps, it was no substitute for actual reconnaissance.

Untersturmführer (2nd Lt.) Erich Heller, a platoon leader in the Panzer- grenadier regiment’s 1st Company, was concerned about the lack of firsthand information and said so. Despite being a junior officer, he requested some scouts to precede the column.

This request was denied, though several others expressed apprehension about not only the lack of reliable information but also the lingering threat of American “jabos,” a shortened slang version of “jäger-bomber”—the almost ubiquitous ground attack fighters that seemed to German soldiers to be everywhere by this stage of the war. The poor winter weather during the Bulge fighting kept the American aircraft at bay most of the time, but occasionally the weather cleared long enough for the deadly planes to take flight, scouring the landscape in search of German columns. Whatever concerns existed, the attack was nevertheless ordered to proceed.

Around 8 AM the Panther tanks set out on the road leading from Odeigne to Oster. Erich Heller’s platoon of infantry rode on the tanks’ engine decks, each vehicle carrying six to eight soldiers; a few walked behind the tanks when their movement slowed near Freyneux. The Odeigne-Oster road intersected the road to Freyneux just east of the stone bridge the Americans assumed any attacking force would have to use.

The leading four Panther tanks were from the 1st Platoon of Hargesheimer’s 2nd Company, commanded by Untersturmführer Fritz Langanke. This 25-year-old veteran had been in the SS since 1937 and had been personally responsible for the destruction of 19 enemy tanks; he wore a Knight’s Cross at his throat, awarded the previous August. Langanke had only been an SS officer for a few months, having been promoted the previous September. His platoon was ordered to proceed to Freyneux and ensure it was clear of American troops.

Now, looking at the bridge leading to the village, Langanke became suspicious. He could see objects on the bridge that looked like landmines. Deciding not to take a chance on the bridge, he instead ordered his platoon to attempt to ford the narrow River Aisne a short distance to the north.

A suitable spot was soon found; the riverbed was firm and seemed able to support the bulk of the 50-ton Panthers. The platoon began fording the river but quickly discovered the far bank was steep, making it difficult for the tanks to climb. One tank nearly overturned, but finally all four were safely on the opposite bank and closer to Freyneux.

A meadow north of the village lay before them, and the platoon could easily cross it to get to Freyneux. Meanwhile, the rest of the company, led by Hargesheimer, crossed the river to the south of the bridge and began taking up position overlooking the village. This meant four Panthers were moving toward Freyneux while seven more waited on the west bank of the Aisne. The river crossing had separated the two groups somewhat but they were still proceeding with their plan.

As Langanke’s platoon clanked toward Freyneux his tank was on the far right of his line. Trailing slightly to his left was Oberscharführer (Sergeant) Kurt Pippert. To his left was the tank of Oberscharführer Kirchner and the last Panther, on the extreme left of the formation, was commanded by Untersturmführer Kurt Seeger, leader of the company’s 2nd Platoon. Unwilling to get back on the road, which would have required the platoon to advance in a column rather than a line, Langanke kept his tanks moving across the wide, sloping meadow. A few trees dotted the field, which sat on a slight rise, allowing the Germans to look down onto Freyneux. So far they had not seen any American presence but continued their wary advance.

In Freyneux the Americans quickly became aware of the advancing enemy tanks. The morning quiet was broken by the sound of the Panthers’ 700-horsepower Maybach engines, and the American reconnaissance troops dug in around the village soon caught sight of them crossing the meadow to the north. The American tanks were generally laid out to defend against attacks from the south and east. The Germans were unwittingly outflanking the American defenders.

Corporal Jim Vance was standing in the commander’s hatch of D-31, still parked behind the church wall. Suddenly he saw a GI on foot running up to his tank. The soldier climbed onto the turret and excitedly told Vance four enemy tanks were moving up the hill to his left front and would be in sight within moments. The corporal shouted to his driver to start the engine while he traversed the Sherman’s turret to face the oncoming Germans.

Nearby, Sergeant Reece Graham and several of D-32’s crew were sheltering in a house next to their tank when Platoon Sergeant Alvin Beckmann burst through the door and told them enemy tanks were coming. The men quickly forgot the coffee they were brewing and rushed outside and scrambled into their tank.

As the American tankers prepared to fire, the four Panthers continued to close on Freyneux. Corporal Jim Vance looked through the sight of his Sherman’s 76mm gun at the line of four tanks. They had just come over the crest of the hill, and luck was with Vance. In a frontal confrontation with a Panther, the Sherman was at a decided disadvantage, even with the more powerful 76mm cannon. The Panther boasted up to 100mm of sloped armor the American tank couldn’t reliably pierce and had much more powerful armament.

The side armor of a Panther, however, was only 40 to 45mm thick, well within the ability of the American tank to penetrate. These four Panthers, obviously unaware of D-31’s presence, were presenting their vulnerable sides to Vance.

The young corporal sat on the right side of the turret next to his cannon. He peered through the telescopic sight, which magnified the view of his foe by a power of five. A periscopic sight sat just above the telescopic sight. The range was less than 500 yards. His left hand rested on a small wheel which controlled the gun’s elevation, allowing him to make small corrections. With his right hand he used a joystick tht allowed him to traverse the turret and keep the gun centered on the moving Panthers. There was a trigger on the joystick for firing; alternately Vance could fire his cannon by pressing a button on the floor with his foot.

Normally Lieutenant Myers would call out firing instructions from the commander’s hatch, but with the officer away at a meeting Vance would have to act alone. Nevertheless, the corporal from Pittsboro, Mississippi, was prepared to do his job that morning.

Setting his sights on the second tank in line, Vance took careful aim at its side and fired. With a crash the 76mm gun sent an armor-piercing round flying toward the Panther at 2,600 feet per second. The cannon recoiled next to Vance, ejecting the spent round’s casing, which clattered into a small basket. The tank filled with smoke and fumes from the burning propellant; two small exhaust fans worked to draw the noxious vapors out of the turret as the loader moved to throw another round of ammunition into the breech of the gun.

In the meadow the Panthers were continuing their slow advance when Vance’s shot crashed into the side of Kurt Pippert’s Panther. The round went through the thinner side armor and into the tank’s ammunition stowage, immediately starting a fire. The crew began to bail out, standard practice on both sides when a tank received a serious hit.

The panzergrenadiers on the engine decks of all four Panthers quickly jumped down, moving to cover in a small ditch nearby. If there was to be an armor battle, the last place the infantrymen wanted to be was on the tanks. Vance quickly moved on to his next target. He later recalled, “When I saw I had hit one of the attacking tanks, I came up from my sights and fire controls to locate another tank. I picked up the second tank and immediately went back to my sights and fired. Again the round hit and I saw the tank become enveloped in fire and smoke.” Again the 76mm gun thundered, sending another deadly shell into the side of a different Panther, causing it to burst into flames.

Fritz Langanke was standing in the hatch of his tank when the hastily planned ambush was sprung. He watched as Pippert’s tank was hit first and the crew bailed out. The vulnerable panzergrenadiers ran for the comparative safety of a nearby ditch, getting as low as they could. Their leader, Erich Heller, the junior officer who had earlier requested scout troops, was on the back of Langanke’s tank but went with his men. Before he could react further, a second Panther burst into flames. It was Kurt Seeger’s tank.

As Langanke took in the horrid spectacle, he thought he saw Seeger jump out of the hatch onto the snowy ground. In actuality, Seeger’s gunner, Fritz Nolte, had pushed the officer out of the hatch so he could quickly follow him out of the flaming wreck. Nolte realized they had been struck in the front of their tank, a lucky hit. “We received a hit in the underside plating at the front of our panzer. Due to a slope in the terrain we presented our weak spot.” Half of Langanke’s platoon was now out of action.

Corporal Vance now set his sights on Kirchner’s tank, but as he prepared to fire, he saw that another American tank had hit it. Instead of firing at it he began searching for the fourth Panther. Before he could find it, a shot from Langanke’s tank slammed into the wall D-31 was sheltering behind. Unable to find the enemy tank to return fire, Vance prudently had his driver back D-31 to a new position behind the church. Meanwhile, Kirchner’s Panther survived the hit from the other Sherman and began to withdraw.

This left Langanke and his crew alone, but he ordered the tank forward anyway. His gunner, Rottenführer (Corporal) Paul Pulm, began firing at whatever targets he had. Alvin Beckmann’s tank, D-34, soon fell victim to Pulm’s accurate fire. Beckmann had returned to his tank after warning Reece Graham of the advancing Germans. D-34 was still sitting behind the woodpile, and Beckmann ordered the driver to start the engine. The cold weather had affected the Sherman’s engine, which wouldn’t turn over, leaving the tank stuck facing east. Beckmann ordered the gunner to traverse the turret to the tank’s rear and engage Langanke’s Panther, but it was too late.

Langanke’s Panther was now just 100 yards from D-34. Pulm took aim and sent a round into the American tank’s turret, starting a fire; the GIs bailed out as the flames spread. Unfortunately, D-34’s driver, Corporal Conrad Bliemeister, couldn’t get out; his hatch was jammed and wouldn’t open far enough to allow him to exit. In desperation, with the fire’s heat making the tank’s interior unbearable, Bliemeister stripped down to his underwear, making him thin enough to squeeze through the narrow opening and escape. He ran through the cold and snow to a nearby home and took cover. Outside, D-34 burned.

After disposing of D-34, Langanke directed Pulm to fire on another Sherman partially concealed nearby. This was D-32, Sergeant Reece Graham’s tank. His tank was also hidden behind a stone wall, but this didn’t stop the German gunner from trying to destroy it.

“I saw a flash from the panzer, the shell hitting the building near the eaves of the house, sending debris all over us,” Graham said. “The panzer then fired another round and missed, hitting the same area.” Graham’s gunner returned fire, shooting two or three rounds at the Panther without scoring a hit. The Nazi tank was in a small depression, and the GI gunner could only see the tank’s turret and gun barrel.

As Graham watched his gunner trying to engage the nearby Panther, he saw a hint of movement farther up the hill, far beyond the meadow. It was the 3rd Company of SS Panzer Regiment 2, the other tank company that had been assigned to this attack. The German plan was for Hargesheimer’s company to clear Freyneux while the rest of the Kampfgruppe continued north toward Oster.

Third Company was following the plan, unaware the road they were using was under observation by the Americans in Freyneux. Due to the angle of their movement, these Panthers were also presenting their weaker side and rear armor to the Americans, though at a much longer range of 2,000 yards.

Graham took a chance and ordered his gunner to refocus on the distant, more vulnerable tanks on the road. “I then gave the orders. ‘Right front! Right front! Range 2,000! Fire!’” Graham said. “After firing, I saw the AP with tracers direct in line, but short. I then ordered the gunner, ‘Up 2! Fire!’ The second shell went straight into the panzer and it started burning.

“I was watching it with field glasses and to my surprise saw another panzer move from right to left behind the burning tank. I then gave the gunner orders, ‘Left! Up 2! Fire!’ The shell went straight into the rear.” Three Germans, including the company’s senior NCO, died in one of the Panthers. The rest of the 3rd Company tanks scattered eastward into some woods to take cover from D-32’s murderous cannon fire.

As Reece Graham was distracted by the Panthers on the Odeigne-Oster road, Fritz Langanke found his tank under attack from a new quarter. Very quickly, several rounds impacted on his frontal armor, though none penetrated. Searching for the source, Langanke saw it was coming from an area covered with bushes to his right from the woodpile where D-34 was burning.

He realized it had to be coming from at least a pair of antitank guns, judging from the rate of fire. The guns were close, no more than 200 yards or so. “Their field of fire was obviously restricted. They were firing only at our hull,” Langanke recalled.

Langanke ordered the turret turned toward the antitank guns. The undergrowth was so thick he couldn’t spot the American guns, so the gunner began spraying the area with machine-gun and cannon fire to strip away some of the foliage. The weather had cleared enough for the sun to appear, leaving a glare on the snow that also kept Langanke from pinpointing his opponents.

Soon the Panther had suffered 10 hits to its frontal armor, splitting the welds. (This was a problem for German tanks that is little known today; even hits that did not penetrate could crack the welded seams of the thick armor plate. Shortages of molybdenum in the factories in Germany could also make the armor brittle, causing it to crack.)

Another round struck the tank’s turret and glanced away. Langanke ducked when the round hit, but a piece of it hit him in the head. It was only a glancing blow, but it rendered him senseless for a few seconds. When he came around, Langanke decided his crew had risked enough and ordered the tank to withdraw. The driver backed slowly away, keeping his frontal armor toward the antitank guns. After a few harrowing minutes the Panther dipped into a depression, giving it cover from the American fire.

Langanke then directed his battered machine away from Freyneux under cover, finally crossing the road just short of the stone bridge and moving into a concealed position in some pine trees; Kirchner’s damaged tank had already arrived there. They were just a short distance north of where Obersturm- bannführer Hargesheimer sat with the rest of the company.

As Langanke took stock of his situation, Hargesheimer advanced on Freyneux from the east with his remaining tanks, seven Panthers advancing in a line. As they crossed another open meadow, Hargesheimer spotted an American tank at the edge of Freyneux and instructed his gunner to destroy it. The tank, a light M-5 Stuart, was quickly dispatched, although the German officer recalled it did not burn. The Germans continued advancing.

The destroyed Stuart was Sergeant Adolfo Villanueba’s. He remembered his tank taking two direct hits. He and his crew bailed out, though his men later retrieved the Stuart’s machine guns and set up a defensive position in a nearby house.

As the SS troops pressed their advantage, several Shermans were shifted to deal with them. One of them caught Villanueba’s eye, and he led it into a good position where it opened fire on a Panther, disabling it. By luck this was the company commander’s tank. Hargesheimer recalled his tank was hit multiple times, the gun disabled, and his loader wounded.

With his tank numbers rapidly dwindling and stiff resistance from the Americans steadily growing, Hargesheimer realized it was time to withdraw and regroup. As his remaining six Panthers drew back with his damaged panzer, one was knocked out and another immobilized. Hargesheimer got his remaining tanks back into cover.

“After our attack foundered, we withdrew into our initial position and each panzer sought cover either in the forest area or in another site that offered potential,” he stated. “After I climbed out of my disabled panzer, I made my report to the nearby regimental command post, where I then waited for further operational orders. That did not prevent me from checking at intervals on the position of the panzers of my company.”

The attack on Freyneux was over, but there was still fighting to be done that day. The weather was clear enough for American air power to make its presence known. Soon fighter bombers began to attack the German positions, particularly the wooded area held by the 3rd Company. Strafing runs with machine guns and cannon were accompanied by bombs dropped all around the SS troops east of the village. Corporal Jim Vance, his tank still hidden behind the church, watched the planes making their runs, calling it “a beautiful sight.”

For Fritz Langanke the jabos were anything but beautiful. Each time a flight of fighters appeared overhead he tensely waited for them to attack his position. The only time he could relax was when they finished their runs and disappeared into the distance. Nearby a 37mm flak gun fired at the American planes, though it never brought one down.

Corporal Jim Vance and D-31 stayed near the church during the rest of the engagement. After the fighting started Lieutenant Myers left the hastily ended officer’s call and rushed back to his tank with Lieutenant Hovland in tow. The two officers reached the tank after Vance finished his part of the engagement.

With Myers back with his tank, Hovland decided to ascend the church steeple so he could direct artillery fire onto the nearby Germans. After he got to the top Hovland began relaying spotting information down to the tank for the task force’s artillery battery to use. Soon they began to adjust their fire onto the now beleaguered SS unit.

Unfortunately for Hovland, his career as a forward observer was brief. The panzer crewmen knew the steeple was a likely observation post and quickly began firing at it. “I got out of there quick. They just blew off part of the steeple,” Hovland said. Even after he reached the ground enemy fire hounded him. A 75mm round struck a wall just behind him as he dove to the ground. He got up to run again, and a second round hit the wall just ahead of him. He stayed down for a few minutes before sprinting back to his platoon.

Earlier in the battle, Untersturmführer Erich Heller and his panzer grenadiers found themselves stuck in a ditch while the tankers of their Kampfgruppe fought and died. Now the young officer watched as American jabos raced overhead to drop their deadly payloads on his comrades along the Odeigne-Oster road. Heller decided to take action and pay the Americans back.

He led his men down the ditch, crawling low to remain out of sight until they reached the nearby road leading into Freyneux. The best option open to him was to send his troops down each side of the road and seize some of the buildings at the northeast end of the village.

Heller sent a runner back to his superiors requesting at least a company of infantry along with armor and artillery support. Instead, he received a platoon of panzergrenadiers and an order to attack with what he had. Despite the odds against the SS men, Heller ordered the attack.

Keeping some machine-gun and panzerfaust teams in the rear of his formation for fire support, he sent the rest down the road. With his heavy weapons laying down effective suppressing fire, the German infantrymen were able to get into the nearest homes. Soon they consolidated their gains and resumed their advance.

As the SS troops again moved forward into Freyneux, however, they were greeted by a hail of American machine-gun fire; a Sherman tank had gotten into position ahead of them and laid down a veritable storm of .30-caliber bullets. The American tankers particularly targeted the panzerfaust carriers, and soon they were all down.

Then the U.S. reconnaissance troops joined in, adding their own rifle fire to the fusillade the Germans were enduring. The German infantry was stopped cold, but they stubbornly held the houses already taken.

Despite the difficulties the Germans were having, Major Coughlin was becoming con- cerned about his ability to hold Freyneux. He sent a radio message to nearby Lamormenil, where the paratroopers were still holding their ground. The captain in charge of that village sent a platoon of men under Lieutenant Thomas De Coste. They rushed to Freyneux across some 400 yards of open fields and took positions around the village, content for now to bolster the existing defenses.

After holding his position for about an hour, Heller realized he’d shot his bolt. Many of his men were wounded, and several American tanks were seen to his south. The Germans withdrew in relays with the remaining troops laying down covering fire to aid their retreat. Soon only Heller and three soldiers were still occupying the house. They still had one machine gun and a panzerfaust. As they prepared to retreat, a Stuart tank and one of the American 3-inch antitank guns were spotted only 120 yards away.

The Stuart tank belonged to Lieutenant Thomas McKone. He got out of his tank because the firing stopped and was standing near another soldier. Suddenly McKone heard the sound of a panzerfaust firing and dove to the ground just before the round slammed into his tank. The vehicle was knocked out, and the soldier with McKone was killed.

With the tank out of action, Heller and another German opened fire on the crew of the antitank gun with their last machine gun. The hail of gunfire succeeded in pushing the crew to cover, away from their weapon. Satisfied, Heller ordered his men to retreat one at a time.

Before they could get away, though, Major Coughlin arrived in his jeep with a driver, Private Harvey Miller. Seeing the American crew had abandoned their antitank gun, Miller and another soldier manned it and began firing into the German strongpoint. One round blasted the house Heller occupied. He was knocked unconscious by the blast, and when he came to he discovered he was pinned beneath the rubble of what had once been the ceiling. The rest of the structure was in flames.

Heller called for help, but his men had already gone. Trapped and alone, the situation seemed dire for the SS officer. Then a group of three GIs led by Private Miller, the man who had fired the shot that immobilized Heller, came into the blazing structure and rescued him. The Americans carried Heller back to their lines while Miller conversed with him in German. After a brief interrogation by Major Coughlin, Heller was taken away to spend the rest of the war in a POW camp.

Aside from sporadic long distance German shelling from Hargesheimer’s Panthers, the fighting for Freyneux was now drawing to a close. There was one more tragic moment to play out, and it would end in favor of the Germans. Fritz Langanke’s tank was still under cover but had a view of a hill north of Freyneux, about 1,000 yards away. All but one of the crew was out repairing links in their tank’s tracks, damaged in the earlier fighting.

Inside the tank, gunner Pulm sat looking through his sights. The hill seemed a likely avenue for an enemy counterattack, and Pulm had used his machine gun to range various points on the hill to determine the exact distances. As they worked, another SS officer came by to gauge the condition of the tank and to tell Langanke of the death of a comrade nearby.

Suddenly, Pulm saw an American Sherman appear on the hill. Within seconds three or four more M-4s came into view. They were a platoon from C Company, 14th Tank battalion of the 9th Armored Division. Throughout the day they had manned a roadblock to the north. Now they were trying to return to their unit but were unaware of the fighting around Freyneux.

As the American tankers drove south, they had no idea they were in the sights of the enemy. Langanke shouted a warning to the men outside the tank and gave the order to fire, but the visiting officer didn’t hear him. The Panther’s gun roared, the muzzle blast blowing off the man’s cap and stunning him.

The first German shot struck a Sherman in its gun barrel, sending fragments into the face of the tank commander. Succeeding shots set the Sherman on fire, and the crew bailed out. Within seconds, three more tanks were knocked out as Pulm calmly fired round after round. The fifth Sherman quickly withdrew over the hill, leaving four wrecks smoldering, their crews sheltering in a small ravine. It was a grim revenge for the German defeat and the death of Langanke’s friend.

As evening fell, Hargesheimer’s tanks were ordered to withdraw to Odeigne. While there would be a few skirmishes and much patrolling over the next few days, the battle for Freyneux was over.

The fighting in the village on Christmas Eve was costly to both sides. Aside from the human toll in casualties, burning tanks littered the battlefield. The Americans lost five Shermans and two Stuarts, while the Germans lost five Panthers with several more damaged. These raw numbers fail to state what is most significant; the outgunned GIs held Freyneux at the end of the day, upsetting German plans for further action elsewhere.

The commonly held view is that German armor always outmatched its American opponents. Here the GIs showed that stereotype to be untrue. Tank battles are more than just a number of vehicles banging away at each other. Tactical ingenuity and courage played their part on each side that day.

Armored engagements are most often won by the side that first spots its foe and opens fire effectively. Once Langanke’s platoon was fired upon with good result, the rest of the German attack devolved into an uncoordinated struggle that the experienced Americans were able to repel despite having fewer, less powerful tanks.

It was a grim Christmas for the soldiers of Task Force Kane, but their victory was a hard-earned gift.

Great story. God bless our vets.

This is the kind of article I prefer, not a person documenting how armys, corps, divisions, brigades and companies moved.

Thanks, David