By Michael E. Haskew

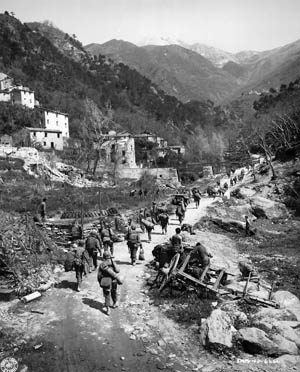

For the Allied armies in Italy, the final winter of World War II was one of planning, replenishment, and the continuing effort to make existence in a war-ravaged land in the midst of snow and ice as bearable as possible.

Large-scale offensive operations were set to resume in April 1945, but the capture of the city of Bologna, its strategic importance as a communications center diminished, would not be the primary objective. The advance of both the Fifth and Eighth Armies in wide converging arcs might cut off the escape of thousands of German soldiers and push the enemy out of Bologna in the process.

The Attrition Losses of German Army Group C

Exposure to the elements still took its toll. The prospect of more mountains, more mud, and more Germans, compounded by the absence of a clearly defined objective such as the capture of Rome had been the previous year, was worrisome. Commanders, perhaps somewhat disillusioned themselves, maintained a vigil against sagging morale. On the positive side, an acute shortage of artillery shells had been alleviated. In fact, ammunition dumps were filled to capacity and another 20,000 tons remained some distance away at the port city of Naples.

The situation for German Army Group C was growing more desperate, even though its troops occupied strong defensive positions in the remaining mountains under their control and along the Senio River. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander of Army Group C, had been involved in a serious auto accident in October 1944 and was unable to return to his post until January. The interim commander of Army Group C was the capable Col. Gen. Heinrich Gottfried Otto Richard von Vietinghoff genannt Scheel, who had led the Tenth Army in multiple delaying actions that had frustrated the Allies time after time during more than 15 months of combat on the Italian mainland.

To the Germans’ backs, the ribbon of the Po River might allow for some delaying time when the Allies renewed their offensive in the spring, but the Po was too long to defend for an extended period. The imposing peaks of the Alps, however, formed a natural barrier to any armed force. Occupying prepared defenses there, the battle-hardened Germans might hold their enemy at bay indefinitely.

The strongest incentive for the German soldier was not necessarily ideological. He was defending his homeland, and the war was going badly on all fronts. Hitler’s bold Ardennes offensive in the West had clearly failed by January, and at the end of the month the Red Army had established a bridgehead across the Oder River, a scant 50 miles from Berlin. Only 5,600 replacement troops reached Army Group C during January 1945, while nearly 14,000 casualties were incurred, including 1,300 killed and 7,700 ill with maladies ranging from frostbite to respiratory infections.

Operation Encore

On the Eighth Army front, General Richard McCreery assumed command from General Oliver Leese on December 31, 1944, and ordered the V Corps to eliminate the last two German bridgeheads on the east bank of the Senio during the first week of 1945. Still reeling from a December debacle during which elements of the division had been battered by the Germans along the banks of the Serchio River, the beleaguered 92nd Infantry Division was ordered in February to improve its positions along the Fifth Army line in the Serchio Valley and to capture neighboring hills.

Initially, the Americans took high ground in the Serchio but were forced to give it up. A German counterattack threw an entire battalion of the Buffalo Soldiers—black troops who had adopted the nickname given to black cavalrymen by Native Americans during the westward expansion of the United States decades earlier—into disarray, and further offensive action by the 92nd Division was canceled.

The only other limited objective offensive undertaken by the Allies during the winter of 1944-1945 was codenamed Operation Encore. With the promotion of General Mark Clark to command of 15th Army Group in December 1944, General Lucian Truscott was elevated to command of the Fifth Army. Truscott viewed a 10-mile stretch of Highway 64, a major road through the valley of the Reno River and into Bologna, as threatened by Germans holding two ridge lines, which reached heights of 3,000 to 5,000 feet. These ridge lines were in the sector of the recently arrived 10th Mountain Division, troops specially trained for combat in rugged terrain, and known to the soldiers as Riva Ridge and Monte Belvedere-Monte della Torraccia Ridge. If these heights, which were 20 miles from the Po Valley, could be taken, then Highway 64 would be further secured, several low ridges could also be wrested from the Germans, and secondary routes winding down into the valley would be open.

The 10th Mountain Division Arrives in Italy

The saga of the 10th Mountain Division is unique in the history of the U.S. Army, and its arrival in the Italian Theater was a noteworthy event. A brand new division of infantry was a rare sight among the battle-weary soldiers of the Allied Fifth and Eighth Armies, and these fresh troops were already considered elite.

The 10th Mountain Division had not fired a shot in anger when the first of its soldiers reached Italy on December 27, 1944. Their “status” was not born of battlefield exploits. It was more a logical conclusion drawn by many, both within the military establishment and outside it. The 10th Mountain had been conceived as the first of three divisions specifically outfitted and trained for winter warfare. These were soldiers whose basic equipment included skis, and each man had been required to present written recommendations for inclusion in the unit.

The father of the 10th Mountain Division was Charles Minot Dole, the founder and chairman of the National Ski Patrol, who had petitioned Congress for the formation of such a unit. Constituted at Camp Hale, Colorado, in the summer of 1943, the ranks of the 10th Mountain included many of the finest skiers and winter sports enthusiasts in the United States. Ski instructors and competitors from across the country volunteered. Malcolm Douglass, who had driven a dog team during Admiral Richard Byrd’s expedition to the South Pole in 1940, came forward, as did Norwegian-born Torger Tokle, holder of the world ski jumping record. When Ludwig “Luggi” Foeger, an Austrian ski jumper and director of the Yosemite Ski School, decided to join up, he first went directly to Dole for an endorsement.

The majority of the 10th Mountain personnel were college educated and members of families that were at least affluent, often wealthy, and sometimes politically connected. As a matter of course, the veterans of other units resented the apparent aristocratic flair of the ski boys. Primarily because of its concentrated mountain training and light complement of artillery, which included three battalions of 75mm pack howitzers rather than the 105mm and 155mm guns of the standard division, the 10th Mountain had stood on the sidelines for months as commanders in other theaters had declined to employ them.

In the snow and ice of Northern Italy, however, troops trained in mountain warfare might be used to advantage. Still, observers wondered openly whether these soldiers could fight. They did not have to wait long for an answer.

“You are Carrying the Ball”

In the gathering darkness of February 18, 1945, skilled climbers of the 86th Infantry Regiment shouldered ropes and gear for the ascent of 1,500-foot Riva Ridge. Intelligence reports indicated that the top of the ridge was lightly defended, and a full battalion reached the summit without difficulty. The surprised German defenders from the 232nd Fusiliers and the 1044th Infantry Regiment were able to mount only feeble counterattacks.

That evening, troops of the 85th and 87th Regiments moved on to Monte Belvedere and attacked from two sides. Choosing the advantage of surprise over a preparatory artillery barrage, the troops of the 87th were in the midst of the German defenders before the enemy fought back. The 85th did not encounter resistance until within a scant 300 yards of the summit but carried it within hours. Elements of the 714th Jäger Division and the 1043rd and 232nd Infantry Regiments counterattacked Monte Belvedere the following day but were driven off by the mountain troops. Monte della Torraccio was occupied on the 23rd.

General Willis D. Crittenberger, commanding the IV Corps, was elated. To General George P. Hays, commander of the 10th Mountain Division, he radioed, “You have done a wonderful job. All eyes are on you. You are carrying the ball.”

Early in March, the 10th Mountain, supported by the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, completed the operation by capturing Monte Grande d’Aiano, Monte della Spe, and Monte della Castellano. The division had lost 1,500 casualties, including 309 killed. A captured German officer commented, “We didn’t realize that you had really big mountains in the United States, and we didn’t believe your troops could climb anything that awkward.”

General Truscott’s limited offensive had succeeded in bringing the IV Corps front even with that of the II Corps, providing excellent jumping-off positions for the coming spring offensive. He was aware, however, that a continuation of the fighting in February could rouse Kesselring to reinforce defenses farther along Highway 64 as he surely had already done on nearby Highway 65. Therefore, Truscott halted offensive operations, and a lull several weeks in duration set in all across the front.

Kesselring was called to Berlin on March 8 and informed by Hitler that he was to take command of German forces on the Western Front, which was rapidly deteriorating after the failure of the winter offensive in the Ardennes. In the East, the Red Army was fighting its way toward Berlin, and it was apparent that the German capital would be the front line in a matter of weeks. When Hitler asked Kesselring to suggest a successor, the latter evidently put aside the differences between them and endorsed Vietinghoff, who returned to Italy from command on the Baltic front.

Operations on the Allied Flanks

Allied commanders had been considering their options for the spring offensive and settled on April 9, 1945, for the resumption of the campaign. Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, who was elevated to overall command of Allied operations in the Mediterranean Theater in December 1944 and succeeded by Clark at the helm of 15th Army Group, favored a strategy similar to that of previous offensive efforts. The Eighth Army would open with a thrust in the area of Lake Comacchio and the Argenta Gap. Five days later, the Fifth Army would attack into the Po Valley northwest of Bologna. The armies would remain in contact and then fully link up at Bondeno as preparations for the first crossings of the Po were under way. The operation was to be supported by a tremendous combined bombing and strafing effort from the Mediterranean Strategic Air Force, XII Tactical Air Command, and the Desert Air Force.

Prior to the opening of the general offensive, operations were conducted on both flanks of the Allied line. In the east, the British 2nd Commando Brigade conducted an amphibious assault across Lake Comacchio, advanced more than five miles, and netted 800 German prisoners while establishing forward positions for a potential amphibious assault against Argenta. A squadron of the Special Boat Service (SBS), a small, highly trained unit specializing in high-risk amphibious operations, also captured a cluster of islands in the center of the lake. Concurrently, elements of the 56th Division secured a prominent piece of land called “the Wedge” which juts into Lake Comacchio. Against stiff opposition, the troops of the 56th Division captured 700 Germans and established British positions north of the Reno River.

The death of one SBS member during the fighting of April 9 was particularly noteworthy. Major Anders Lassen, Danish by birth, had participated in several clandestine operations previously and was nicknamed the “Terrible Viking” by his German adversaries. As Lassen led a group of 17 soldiers against the garrison of a small town on the edge of Lake Comacchio, the group was challenged by sentries and then taken under fire by machine guns.

Lassen knocked out one position, silencing two machine guns and killing four Germans. Two more machine-gun nests went down in similar fashion. Moving toward a fourth position about 300 yards away, Lassen tossed grenades. He was hailed by a German shouting, “Kamerad!” As he moved forward to take the surrender of the position, a hidden machine gun cut him down. The remaining SBS men wiped the Germans out. Lassen had already been awarded three Military Crosses for heroism under fire. He received a posthumous Victoria Cross for the action at Lake Comacchio.

To the west, the Americans planned to subdue the final German defensive positions of the Gothic Line along their front by capturing the town of Massa. General Truscott chose the 92nd Infantry Division, which had recently been reorganized, for the task. Although the division’s overall performance had been disappointing, those fighting men and officers who had done their duty well were consolidated into the 370th Infantry Regiment, while the 473rd Infantry was attached along with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), comprised of Japanese American soldiers who had returned to Italy in March after several months of fighting in southern France.

The 442nd RCT: Proving Their Loyalty

The experience of those who stood in the ranks of the 442nd RCT was somewhat unique in military history. These were Nisei, secondgeneration Japanese Americans who were in fact American citizens by birth. In the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese-American families had been quarantined in a number of internment camps in the United States. While the government had acted in the name of national security, this period of internment is remembered primarily as a great injustice.

Determined to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States, many young Japanese American men considered service in the U.S. Army highly preferable to the restrictive boredom of internment. In the spring of 1942, a volunteer unit of Nisei soldiers, the 100th Infantry Battalion, was formed in Hawaii. The 100th was deployed to North Africa in June 1943 and attached to the 34th Division. Within months, the 100th came to be known as the Purple Heart Battalion because of the high number of casualties it sustained.

On February 1, 1943, the 442nd RCT was authorized by the U.S. government, and the 100th Battalion later became a component of the 442nd. By the end of the war, the 442nd RCT had become the most highly decorated unit in American history. Its soldiers received more than 18,000 decorations for combat bravery, including two Medals of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, and 9,500 Purple Hearts. The 442nd first fought as a cohesive formation in Italy. Transferred to southern France following the commencement of Operation Dragoon, its soldiers gained lasting fame during an operation to link up with the “Lost Battalion,” the 141st Infantry, 36th Division, in the Vosges Mountains.

The 442nd and 473rd Regiments, fighting in relief of the 370th, succeeded in capturing several mountain peaks during a rapid advance that drew a regiment of the 90th Panzergrenadier Division away from the Eighth Army front. After six days of combat, Massa was in Allied hands, but stiffened German resistance had brought the limited offensive to a halt. At Monte Fragolita on April 5, Pfc. Sadao Munemori sacrificed his own life to save two of his comrades by falling on a German grenade that had landed in their foxhole. Munemori received a posthumous Medal of Honor for his act of heroism.

Crossing the Senio

On the morning of April 9, nearly 2,300 Allied medium and heavy bombers began a two-day campaign to soften German defenses prior to the scheduled jump off of the Eighth Army at 7:30 pm. Supported by tanks, some of which were the fearsome flamethrowing Churchills which the troops had nicknamed “crocodiles,” the thrust of General C.F. Keightley’s V Corps rounded up 1,300 prisoners during the opening hours of the offensive. The 2nd New Zealand and 8th Indian Divisions crossed the Senio River, while the Polish II Corps encountered the crack 26th Panzer Division. Two brigades of the Polish 3rd Carpathian Division nevertheless succeeded in bridging the Senio the following morning. The next river, the Santerno, was crossed during the early hours of April 12, and the 56th Division initiated several amphibious moves that threatened to encircle the 42nd Jäger Division.

During the Senio crossing on April 9, Jemadar Ali Haidar, a havildar (sergeant) of the 13th Frontier Force Rifles, was one of only three men in his battalion section who reached the far side of the river, the remainder being pinned down by enemy machine-gun fire. Ali Haidar advanced alone and threw a grenade into the first enemy strongpoint he reached. At the same time, a German grenade exploded nearby and seriously wounded him. Despite his injuries, Ali Haidar forced the Germans to surrender. He was wounded again, in the arm and leg, but moved on to a second machine-gun nest, wounding two of its occupants and forcing the other two to surrender.

The way now open, the remainder of the company crossed the Senio and established its bridgehead. Ali Haidar received the Victoria Cross for his courage under fire. After the war, he returned to his native Pakistan. He died in 1999 at the age of 85, the only Pathan awarded the Victoria Cross during World War II.

Breaking Through the Genghis Khan Line

The 78th Division passed through the ranks of the 8th Indian Division, advanced to the Reno River, and captured a key bridge by April 14. General Vietinghoff had patched together a final defensive perimeter before Bologna, but Allied troops were quickly through the perimeter of this so-called Genghis Khan Line. The German situation on the Eighth Army front was rapidly deteriorating. By the 18th, two battalions of the 78th Division had occupied and passed northwest of the town of Argenta.

Vietinghoff had warned the high command in Berlin that the Eighth Army advance threatened to outflank his line along the Reno, and the commander of Army Group C requested permission to withdraw. However, he received a terse reply from headquarters on the 17th.

“All further proposals for a change in the present war strategy will be discontinued,” read the communiqué from Colonel General Alfred Jodl, chief of the high command operations staff. “I wish to point out particularly that under no circumstances must troops or commanders be allowed to waver or to adopt a defeatist attitude as a result of such ideas apparently held by your headquarters. Where any such danger is likely, the sharpest countermeasures must be employed. The Führer expects now, as before, the utmost steadfastness in the fulfillment of your present mission, to defend every inch of the north Italian areas entrusted to your command. I desire to point out the serious consequences for all those higher commanders, unit commanders, or staff officers who do not carry out the Führer’s orders to the last word.”

Vietinghoff was in no position to deny the reality of his plight. The 78th and 56th Divisions were rolling through the newly opened Argenta Gap, while the 2nd New Zealand, 10th Indian, 3rd Carpathian, and 5th Kresowa Divisions pushed forward along Highway 9 in a combined effort by the V, XIII, and Polish II Corps.

1,300 Killed and Wounded

Five days after the Eighth Army’s thrust, the Fifth Army began its drive into the Po Valley. After fog had lifted on the morning of April 14, four days of sustained air support began. More than 2,000 bombers hit German positions supported by massed artillery. The 85th Infantry Regiment of the 10th Mountain Division advanced into the Pra del Bianco, a valley northeast of Castel d’Aiano. When his company met stiff resistance, Pfc. John D. McGrath silenced four enemy machine-gun nests and used a captured weapon in the process before falling mortally wounded. McGrath received a posthumous Medal of Honor. Such individual acts of bravery gave momentum to the effort, and nearby Hill 680 was occupied along with several neighboring prominences.

Meanwhile, the 85th Infantry cleared the village of Torre Iussi and took Hill 903, while the 86th Infantry captured high ground at Rocca Roffeno. The German 94th Infantry Division, in danger of encirclement, began to fall back the following day.

Fighting on Hill 913, 2nd Lt. Robert Dole, accompanied by two other infantrymen, set out in the darkness of the 14th to capture a German prisoner for interrogation. A hidden machine gun cut down the two scouts and seriously wounded Dole, who lost all use of his right arm and later a kidney. The future senator from the state of Kansas and candidate for the presidency of the United States spent 40 months recovering in hospitals.

Although five days of fighting cost the 10th Mountain Division nearly 1,300 killed and wounded, Monte Mantino, Monte Croce, and Monte Mosca were occupied, and by the 18th Allied troops were nearly within sight of Highway 9 and the Po Valley. Armor support and reinforcing troops from the Brazilian Expeditionary Force drew up to exploit the gains in the IV Corps sector.

The Polish II Corps Liberates Bologna

The drive of the II Corps toward Bologna progressed much more slowly. In anticipation of a renewed Allied effort to take the city, the Germans had placed their strongest defenses in the area. On the left, the 6th South African Armoured Division captured Monte Sole in the predawn hours of the 16th, facilitating an advance toward the Praduro road junction on Highway 64. Although the Germans stubbornly resisted along Highway 65, flanking operations by the 91st and 34th Divisions cleared sections of the road. General Truscott repositioned several units, including the 85th Division, into positions previously occupied by the U.S. 1st Armored in preparation for the II Corps to finally break through to the Po Valley.

The 10th Mountain and 85th Divisions began moving once more on April 18. In 24 hours, the 85th was north of the town of Piano di Venola, while elements of the 10th Mountain took Monte San Michele the following day. German resistance began to crumble. An isolated stand at the town of Pradalbino obliged the 87th Infantry Regiment to fight house to house, while armor of the 90th Panzergrenadier Division, desperately trying to stem the tide, was engaged in a tank versus tank battle with the 1st Armored Division. Intercorps boundaries blurred in the race to the Po Valley. Troops of the 133rd Infantry Regiment of the 34th Division hitched rides on tanks of the 752nd Tank Battalion and headed up Highway 65 toward Bologna.

On April 21, as troops of the Red Army battled in the suburbs of Berlin far to the north, the II Polish Corps entered Bologna from the east at approximately the same time as the Fifth Army forces. The Poles were greeted enthusiastically. Seventeen Polish officers were declared honorary citizens of Bologna, and a number of Polish soldiers subsequently received medals inscribed, “To the liberators who were the first to enter Bologna—on 21 April 1945—in honour of their success.”

The liberation of Bologna was the crowning achievement of the Polish II Corps during World War II. Throughout the campaign in Italy, the corps had fought with distinction, suffering 2,301 killed and 14,830 wounded, more than 36 percent of its strength.

“Go For Broke”

The 92nd Division continued to attack in the west, intending to trap German troops at the naval base of La Spezia on the Ligurian coast. The 473rd Infantry reached a position within 10 miles of the base at the junction of Highway 62 and the coastal road, Highway 1. The 442nd RCT faced tough opposition in the mountains. On April 21, young 2nd Lt. Daniel K. Inouye lost his right arm while leading a company in the assault on Colle Musatello.

Inouye was wounded in the side by machine-gun fire but threw a grenade into a German position and killed the crew as the enemy soldiers rose from their cover. He destroyed a second position with a grenade but was driven to his knees due to loss of blood. Undeterred, he crawled forward to attack yet another machine-gun nest.

“At last I was close enough to pull the pin on my last grenade,” Inouye remembered. “And as I drew my arm back, all in a flash of light and dark I saw him, that faceless German, like a strip of motion picture film running through a projector that’s gone berserk. One instant he was standing waist-high in the bunker, and the next he was aiming a rifle grenade at my face from a range of 10 yards. And even as I cocked my arm to throw, he fired and his rifle grenade smashed into my right elbow and exploded and all but tore my arm off. I looked at it, stunned and unbelieving. It dangled there by a few bloody shreds of tissue, my grenade still clenched in a fist that suddenly didn’t belong to me anymore…. The grenade mechanism was ticking off the seconds. In two, three, or four, it would go off, finishing me and the good men who were rushing up to help me.

“Get back! I screamed, and swung around to pry the grenade out of that dead fist with my left hand. Then I had it free and I turned to throw and the German was reloading his rifle. But this time I beat him. My grenade blew up in his face and I stumbled to my feet, closing in on the bunker, firing my tommy gun left-handed, the useless right arm slapping red and wet against my side.”

Grievously wounded, Inouye was evacuated and spent 20 months in various hospitals. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Later, that recognition was upgraded to the Medal of Honor, which was presented to him on June 21, 2000. Inouye was elected to the U.S. Senate from the state of Hawaii in 1962 and continues to serve in that capacity until his death on December 17, 2012. His heroism exemplified the motto of the 442nd RCT, “Go For Broke.” The regiment moved on to eventually liberate the cities of Genoa and Turin.

German Resistance Crumbles

By April 20, it was apparent to Vietinghoff that all of Army Group C was in grave danger. The Fifth Army breakthrough west of Bologna threatened to drive a wedge between the German Tenth and Fourteenth Armies. The U.S. Eighth Army also threatened to encircle the elusive Tenth Army. Vietinghoff took matters into his own hands that day and began a general retirement without orders.

As early as February, high-ranking German officers in Italy had realized that all was lost. One of these, SS General Karl Wolff, who commanded German police and SS forces in northern Italy, had contacted Allen Dulles, head of the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Switzerland. Through diplomatic channels, Wolff communicated overtures of a separate peace in Italy between Germany and the Western Allies. On April 20, Wolff was officially rebuffed due to concerns over the repercussions such a development would have with the Soviets. Two days later, Wolff met with Vietinghoff at the Recoaro Terme in the foothills of the Alps, and the decision was made to surrender German forces in Italy. Further instructions from the high command in Germany would ostensibly be ignored.

On April 21, the Fifth and Eighth Armies linked up north of Bologna and began roaring across the Po Valley. On the 23rd, the 88th Division captured 11,000 prisoners on the south bank of the Po River. Among them was General Friedrich von Schellwitz of the 362nd Division, the first German divisional commander to be captured in Italy. The British 6th Armoured Division encircled the remnants of the 278th Infantry Division near Ferrara and trapped several thousand more Germans of the I Parachute Corps upon contact with the 6th South African Armoured Division near the town of Finale. The entire LXXVI Panzer Corps was pinned in the east between the coast of the Adriatic Sea and the Eighth Army. Many of these Germans simply abandoned their equipment and endeavored to swim the Po River.

Allied crossings of the Po were undertaken against light resistance as early as the 22nd. General Truscott ordered each division of the Fifth Army to cross on its own, given the lack of German resistance. General McCreery’s directive to the Eighth Army was much the same, and elements of both the V and XIII Corps crossed on the 24th. Some concern was expressed that the Germans might attempt yet another organized stand along the banks of the Adige River, and Allied forces made all haste to reach the Adige before that could take place.

Elements of the 88th Division crossed the Po on the 24th and sped 30 miles to Verona in 16 hours, slowed only by sporadic pockets of diehard Germans or of those wishing to make one final defensive effort before surrendering. A few men of the 4th Parachute Division were subdued in the city.

Crossing into Austria

At the same time, a task force under Colonel William O. Darby, the former Ranger commander, headed for Lake Garda and the famed Brenner Pass on the Austrian frontier. To the west, the soldiers of the 92nd Division were in Genoa by the 27th. Partisans had already taken the surrender of the 4,000 Germans in the city. Elements of the Eighth Army crossed the Adige without opposition on the same day. German soldiers surrendered by the hundreds.

By April 26, General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin’s XIV Panzer Corps, instructed to defend a line near Lake Garda, could muster only about 2,000 soldiers. Senger’s purpose in defense was to buy time for Army Group C to coordinate a collapsing withdrawal along with Army Group G north of the Alps in France and Austria and Army Group E, retreating from the Balkans. Field Marshal Kesselring, acting as commander of all German forces in southwestern Europe, hoped that these troops could stand along the Alps for a time, allowing as many German soldiers as possible to surrender to the Western Allies rather than the Red Army.

The following day, Combat Command A of the 1st Armored Division rolled into Milan, and the 442nd RCT sprinted 40 miles to Allesandria, accepting the surrender of the 3,000 Germans there. During the next two days, the 442nd advanced 50 more miles to the west and entered Turin. By May 1, both the 442nd and the 473rd Infantry Regiments had made contact with French troops of General Jacob Devers’s 6th Army Group, which had advanced 60 miles across the French-Italian frontier. During four days of fighting from April 27-May 1, the 10th Mountain Division secured Lake Garda. Tragically, Colonel Darby and several other men were killed on the 29th by a single German artillery shell.

The Eighth Army was restricted by long supply lines and difficult communications. Therefore, only the 56th and 2nd New Zealand Divisions could initially be sustained across the Adige. Resistance was virtually nonexistent, and small bands of German soldiers surrendered readily.

The 56th Division took Venice, and the 2nd New Zealand captured Padua on April 29. Three days later, the New Zealanders entered Trieste after encountering Yugoslav partisans several miles outside the city. Nearly 150,000 German and Italian fascist prisoners had been captured during the final offensive. By May 6, Allied troops were through the Brenner Pass and across the Austrian frontier.

“Imminent Surrender After a Fight Lasting Six Years”

Following weeks of clandestine discussions, the terms for the unconditional surrender of all German forces in Italy were concluded on April 29 at General Alexander’s headquarters in Caserta, near Naples. Amid some confusion, mistrust, and treachery, German diplomatic and military representatives eventually agreed that the cease-fire was to take effect at noon Greenwich Mean Time on May 2, 1945. The Germans, however, delayed their surrender broadcast for two hours. At 6:30 pm, when confirmation that the Germans had released the order was received, Alexander announced the cease-fire to Allied troops.

For his part, General Vietinghoff had been relieved of command by Kesselring for treason because of his unauthorized contact with the Allies. In one of the more noteworthy events during the last days, General Senger made his way under escort to 15th Army Group headquarters in Florence and surrendered to General Clark. The adversaries at last saw one another face to face. “It was,” Senger wrote in his diary, “a tragic moment, the complete defeat and the imminent surrender after a fight lasting six years, tragic even for those who had foreseen it for a long time.”

The Death of Benito Mussolini

As the arduous campaign in Italy drew to a close, one final drama played out. On April 25, as Allied troops drew nearer, Benito Mussolini, the fascist former dictator of Italy, and his mistress, Clara Petacci, departed Milan for a rendezvous with an expected 3,000 loyal fascist soldiers at Como. Together, these stalwarts would fight to the last from an Alpine redoubt. Only a dozen men actually rallied to Il Duce for this final battle, and the small band instead began moving north with a German convoy. The next day, Italian communist partisans led by Count Pierluigi Bellini Delle Stelle, stopped the convoy near the town of Dongo.

Dressed in a German military overcoat and helmet, Mussolini was identified after a partisan noticed the quality of the leather boots he was wearing. For two days, the communists held both Mussolini and Petacci, waiting for instructions from their leaders with the Committee for National Liberation. On the morning of April 28, a partisan named Walter Audisio drove the prisoners to a villa and directed them to stand near a low stone wall. When he pulled the trigger on his weapon, it jammed. Audisio reached for another and shot Petacci. Mussolini opened his coat and muttered, “Shoot me in the chest.” In seconds he was dead.

The bodies, along with those of several other fascists, were taken to Milan by truck and dumped into the Piazalle Loretto. They were subsequently hung by the ankles in front of a garage. Crowds gathered to jeer and spit at the bodies. One woman pumped bullets into Mussolini’s corpse and shouted, “Five shots for my five murdered sons!”

A Questionable Campaign

World War II in Italy was over. Its repercussions would be dealt with for generations to come. For more than 20 months, the two great armies had fought one another, and the casualties had been enormous. German losses have been estimated at more than 434,000, with 48,000 of those killed. Allied dead and wounded in Italy totaled more than 300,000. Historians continue to debate the strategic and tactical merit of many decisions made by commanders on both sides in the theater.

In the final analysis, Allied victory in Italy appears to have been inevitable. Whether it was worth the cost depends on individual perspective. True enough, the Mediterranean became a secondary theater following the Normandy invasion. However, to the men who fought, bled, and died in Italy, this was their battle, their war, and their sacrifice. The effort is worthy of the utmost respect.

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History magazine. He is the author of numerous books and articles on World War II and resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Interesting footnote about the 442nd Regiment.

Hollywood made a movie, “Go For Broke”, about their exploits. My father, who was in the Army at the time, trained some of the actors in how to behave like infantrymen.

Dad said some of the things Hollywood expected — like using a helmet filled with sand for a mortar base — were laughable, but he knew it was just hyperbole. That’s show biz!

This is a fascinating article. The Italian campaign is not one of my ‘strong points’ in the history of the Second World War. I have some knowledge of its progress up to the liberation of Rome, but only the other day I was genuinely wondering ‘what happened next?’ So, this article is timely. It’s well written, featuring some incredible stories of individual bravery, but covering the overall operational effort – and including the contribution of non-American forces, which makes a nice change! 😉 The Italian campaign was a truly international effort and that is abundantly clear from this article. It also highlights the utter insanity of Hitler’s regime, and the enormous, unnecessary cost of the ‘no retreat’ orders. That the average Allied troops did not fight as fanatically as the Germans is often true, but we encouraged our troops to success, rather than threatening them with ‘extreme measures’. I’ve learnt much! Thank you.

Regarding the ‘value’ of the campaign, I find it hard to see an alternative. Once the North African campaign was over, Italy (via Sicily as it turned out) had to be the next step – it began toppling the Axis, as far as that was important. Moreover, it tied down hundreds of thousands of German personnel. Why the Allied leadership felt unable to present to Stalin the Italian front as a (if not THE) second front, I’ve truly never understood.