by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

By late October 1941, the armies of the Third Reich had swept deep into western Soviet Russia. Leningrad lay under siege and panzer spearheads reached to within 40 miles of Moscow. The German Sixth Army, part of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South, occupied Kharkov with the First Panzer Army striking for Rostov.

On Rundstet’s southern flank, General of Infantry Erich von Manstein’s Eleventh Army punched through the tough Soviet defenses of the Perekop isthmus. The 10-day, hotly contested battle for the Isthmus netted 100,000 Soviet prisoners and opened the door to the Crimea.

Soviet Take a Stand a Sevastopol

Through the centuries, a myriad of peoples had fought for and settled in the Crimea. Ancient Greeks, Scythians, Goths, and Tartars came and went. Now the invaders were the Germans of the Third Reich, whose Führer planned to turn the Crimea into a pure German colony. With the main base of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol and within air range of the Caucasus and Rumanian oilfields, the Crimea held strategic importance to both the Nazis and the Soviets.

The Axis troops fanned out east toward the Kerch Peninsula and south toward Sevastopol. There was no way of stopping the Germans on the open steppes. By November 16, all of the Crimea except Sevastopol was in their hands. There, the Soviet Military Council opted to make its last stand.

In the Crimean War of 1854-1855, Sevastopol defied the British, French, Turks, and Sardinians for an incredible 345 days before surrendering. The Soviets were determined to do one better. Master of the blitzkrieg, mobility, and the open battlefield, Manstein was to be tested in one of the most brutal sieges in the history of warfare.

Black Sea Navy guns and crack Marines stiffened Soviet resistance. The defenders counterattacked and flung back General Eric Hansen’s 54th Corps’ probing attacks. One incident saw a politruk (political instructor) and five Black Sea sailors hurl themselves and their last grenades on German tanks to stop a breakthrough to the city. The heroism of the “five sailors of Sevastopol” was remembered in many a song and poem.

The Assault on Sevastopol Begins

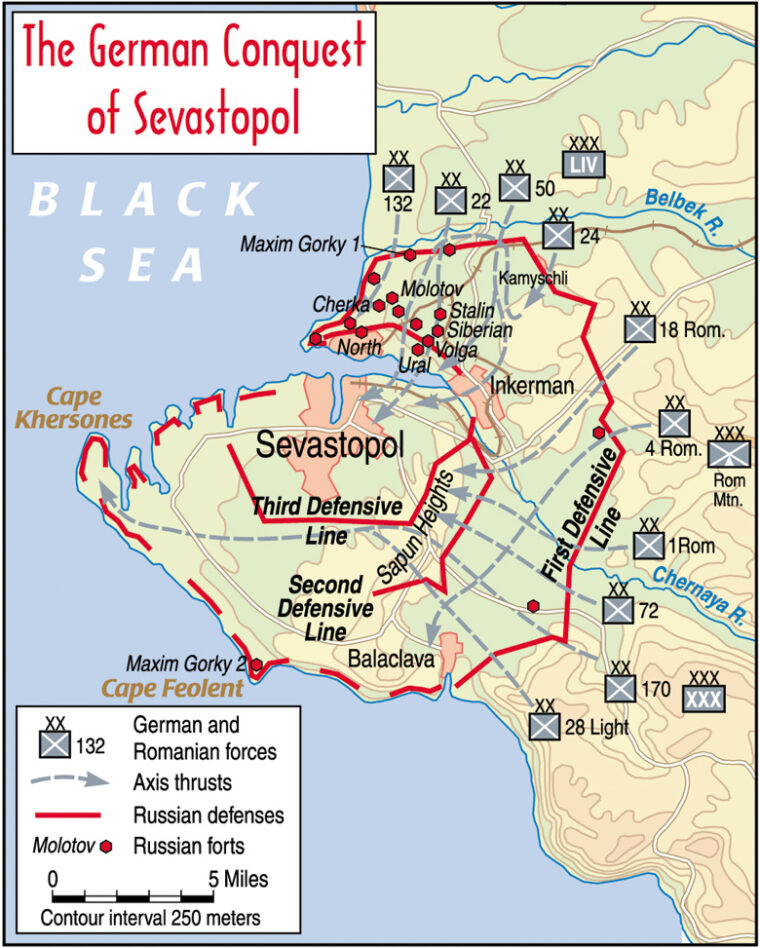

It was clear that nothing less than an all-out assault by the Eleventh Army could hope to take the city. Its natural defenses alone ensured that the fight for the city would be a hard one. The city stood on the northern side of a triangular peninsula that jutted westward into the Black Sea. Immediately to the north of Sevastopol lay Severnaya Bay, while rugged wooded hills and ravines guarded the city and the entire peninsula’s landward side from the east and south.

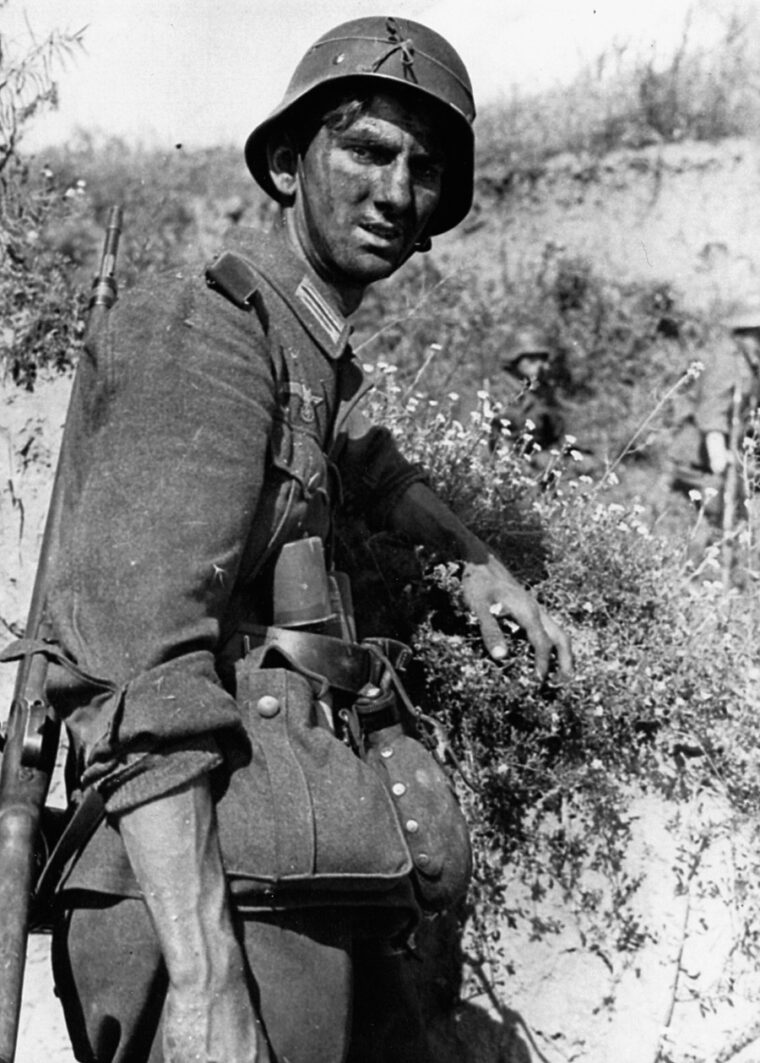

Heavy rains and rough terrain delayed full deployment of troops for a month, so the attack did not get under way until December 17. At first the Soviet defense seemed to crumble, but then it became rock hard. New divisions entered the fray, and officers, commissars, and the NKVD, the Soviet state police, “boosted” morale. Torrential downpours and stormy weather further wore down the German soldiers, many of whom had only summer uniforms.

Fighting around Sevastopol continued into the New Year with the Eleventh Army reaching within five miles of the northern outskirts of the city. At this crucial point, Manstein was forced to divert his attention to the northeast. An unexpected amphibious Soviet counterattack drove the Germans out of the Kerch Peninsula and threatened the rear of his army.

In Sevastopol there was a feeling of euphoria; surely the whole of the Crimea would soon be liberated! Despite the occasional air raid and shelling, people emerged from shelters and caves to repair the damaged city. Their hopes were dashed when the Soviet offensive bogged down into a lengthy stalemate that lasted through the Russian winter.

In mid-May 1942, Manstein, promoted to colonel general, reconquered the Kerch Peninsula, destroying two Soviet armies at the cost of a mere 7,500 German casualties. The people of Sevastopol again disappeared into their underground shelters. They worked double shifts in the armaments works and began to evacuate their children and the elderly. The Soviets’ last attempt to forestall a decisive German drive on Sevastopol had failed.

With the advent of spring, the time for Hitler’s colossal 1942 summer offensive, codenamed Operation Blue, drew near. Hitler planned for a two-pronged attack that would seize Stalingrad on the Volga and drive deep into the oil-rich Caucasus. Preliminary to Blue, it was imperative to finally capture Sevastopol, a thorn in the German Army’s southern flank. Failure to do so meant that substantial German forces would remain locked up to invest the city.

Germans Plan a Second Assault; Sevastopol Strengthens Its Defenses

Supreme Command decided to recommit Manstein’s Eleventh Army for a second assault on what was possibly the world’s strongest fortress. In the words of an American intelligence officer it was a “tough nut to crack.” Virtually the entire 180,000 strong civilian population toiled tirelessly to ensure that the defenses were even more daunting than in the previous November. They blasted bunker, gun, and mortar positions right into the rock, strung barbed wire, dug antitank ditches, and laid a sea of mines, not just in front of the fortified zones but also right inside them. The city’s three defensive lines were 10 miles deep with 220 miles of trenches.

Underground, the civilians worked in appalling conditions to do everything they could to help the defenders above. Sewing brigades fixed damaged military clothing. Pravda correspondent Boris Voyetekhov described the scene of an old woman working side by side with a beautiful young woman. The old woman worked a stamping machine with her remaining hand, having lost her other to a bomb blast. The young woman nursed a baby while working a boring machine at the same time. Others cast shells and repaired countless guns, and in November and December alone manufactured some 20,000 hand grenades and 32,000 antipersonnel mines.

Numerous camouflaged strongpoints commanded the eastern hills while the immense naval guns of a fortress called Maxim Gorky II at Cape Feolent dominated the peninsula’s southern coastline. The weakest natural obstacles were to the north of Severnaya Bay, but here arose gigantic forts. The Germans named them Volga, Siberian, Lenin, Stalin, Molotov, and Maxim Gorky. The proper Soviet designations were numerical, Battery No. 30 for Maxim Gorky, for example.

To man Sevastopol’s defenses, General Ivan Y. Petrov’s Independent Maritime Army fielded seven rifle divisions, one dismounted cavalry division, two rifle and three naval brigades, two Marine regiments, two tank battalions, and various smaller formations. A further 10 artillery regiments, two mortar battalions, and an antitank regiment gave Petrov 106,000 frontline troops, 600 guns, and 2,000 mortars. They were supplied and reinforced by Vice Admiral Filip S. Oktyabrskii’s Black Sea Fleet, including tens of thousands of naval personnel to man forts and guns, and a multitude of Komsomols, the teenage boys and girls of the Communist Union of Youth.

Oktyabrskii was in overall charge of the defense of Sevastopol, with Petrov being the ground force commander. Their main weakness was the lack of support from the Soviet Air Force, which fielded a pathetic 60 old planes in the Crimea.

Women played a major role in the Soviet armed forces, not only as medical staff and radio operators, but also as antiaircraft gunners, tank crews, and snipers. Sevastopol was no exception and featured the famous machine-gunner Nina Onilova, the scout Maria Baida, and the sniper Liudmila Pavlichenko. A veteran of Odessa, Pavlichenko fought in Sevastopol until she was wounded and evacuated. She would finish the war as the top-scoring female sniper of all time with 309 kills, including 78 enemy snipers.

The Eleventh Army’s Massive Force

Manstein’s Eleventh Army consisted of some 203,000 German and Romanian troops. However, after the Kerch battle, Army Group South (now under Field Marshal Fedor von Bock) commandeered his sole panzer division, the 22nd, while his mostly Romanian 42nd Corps was used to safeguard the Kerch Peninsula to prevent a repeat of the earlier Soviet attack there. That left Manstein with seven German divisions, each 20 percent larger than a Soviet division, and initially two Rumanian divisions, the 18th Infantry Division (ID) and the 1st Mountain Division (MD) of the Rumanian Mountain Corps. In addition, the 4th Rumanian MD arrived from Kerch to reinforce the 54th Corps on June 13.

Since the previous December’s failure, Manstein concluded that he required more and heavier artillery, so he gathered 121 batteries of 1,300 guns and 720 mortars, the greatest concentration of artillery pieces ever used by the Germans in the war. They included 190mm cannon; 305mm and 350mm mortars; and 150mm, 210mm, 280mm and even 320mm Nebelwerfer and Wurfrahmen-type rocket launchers, nicknamed “Lowing Cow” by the Russians, the Reich’s answer to the Katyusha rockets that had been nicknamed “Stalin’s Organ.”

Nothing, however, compared to the German super heavyweights, the mortars Gamma, Odin or Karl, and Thor, and the heaviest gun of World War II, Dora. Gamma fired 427mm, one-ton projectiles for a distance of nearly nine miles. It took 235 men to service Gamma. Thor and Odin were even larger, their devastating 2.5-ton, 615mm bombs struck like the hammer of the namesake Norse thunder god to crack even the thickest concrete defenses.

Yet Gamma, Odin, and Thor were whelps compared to the titanic Dora, also known as the Heavy Gustav. Originally designed to destroy the fabled Maginot Line, it took 60 railway cars to transport her components to the Crimea. Once assembled, Dora was 141 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 38 feet high with a weight of 1,329 tons! Protected by two flak battalions, Dora sat 19 miles northeast of Sevastopol on double railway tracks. Her operation required 1,500 men, one colonel, and one major general. Dora’s 107-foot, 800mm barrel fired five-ton high-explosive or seven-ton armor-piercing shells for 29 or 24 miles, respectively. During the siege, she fired 40 to 50 shells at Sevastopol, one of which passed through water and 100 feet of rock to pulverize a Soviet ammunition dump beneath Severnaya Bay.

Luftwaffe Colonel General Baron Wolfram von Richthofen, the nephew of the legendary Red Baron, gave additional firepower with Fliegerkorps VIII’s 600 aircraft, including seven bomber groups. To deal with the Soviet fleet, there was also Oberst Wolfgang von Wild’s small Fliegerführer Süd (Air Command South) and a German and Italian naval flotilla. Manstein’s armored strength included remote-controlled Goliath miniature tanks, which were designed to carry explosives into enemy defenses, and a number of Sturmgeschütz assault gun battalions.

Basically, a tank with a fixed gun instead of a rotating turret, the Sturmgeschütz, or Stug, figured prominently at Sevastopol. Stugs were typically brought into position by night and camouflaged for maximum surprise. Used in concentrations, they advanced together with or directly behind screening infantry, their close-range fire knocking out enemy support weapons. The first versions carried 75mm short-barreled guns capable of dealing with soft targets, but in early 1942, Stugs with long barreled 75mm L/43 antitank guns appeared.

Operation Störfang (Sturgeon Catch)

The weight of the German attack, with Hansen’s 54th Corps, would be in the north. Notwithstanding extremely heavy Soviet defenses, the terrain was the most favorable for ground assaults and for artillery and air support. A secondary attack would come through the hilly southeastern sector by 30th Corps under Lt. Gen. Maxim Fretter-Pico. No major attack was planned from the east due to the extremely rugged and wooded terrain. Here the Romanian Mountain Corps was to pin down the enemy and later aid the German flanks.

On June 2, the roar of the German artillery heralded the beginning of Operation Störfang (Sturgeon Catch), the final assault on Fortress Sevastopol. For five days and nights, German guns and bombers relentlessly hammered the Soviet positions as a prelude to the ground offensive. Eighth Air Corps quickly established air supremacy and in defiance of heavy flak flew over 3,000 bombing missions between June 2 and 6. A deafening orchestra of mortar bombs, screaming Stukas, the metallic rings of the 88mm flak, and the earthshaking projectiles of the gargantuan Gamma, Thor, and Dora burst blood vessels, spread terror, and shattered concrete.

The day after the guns opened fire, Manstein left the 30th Corps’ command post, a small Moorish-style palace perched on a cliff above the Black Sea coast, and boarded an Italian torpedo boat. He personally wished to inspect how much of the coastal road, the main supply line for the 30th Corps, was visible from the sea and threatened by the Black Sea Fleet’s guns. Near Yalta, the idyllic backdrop of white country houses amid green gardens and blue sky was suddenly interrupted when “without warning a hail of machine gun bullets and cannon shells began pumping into us from the sky,” recalled Manstein. Two Soviet fighters swept out of the sun and raked the deck, leaving seven people dead or wounded and the boat in flames. The heroic young Italian captain dived into the sea, swam to shore, and returned to the rescue with a Croatian motor boat.

Manstein escaped the calamity unscathed and soon was back at Eleventh Army’s command post in the Tartar village of Yukhary Karales. He spent endless hours at observation on the cliffs above, in the same mountains where his Germanic Goth ancestors once built their strongholds. The location, roughly between the 54th Corps to the north and the Romanian Mountain Corps to the south, offered a panoramic view of the entire battlefield. Alongside Manstein was his chief of operations, Colonel Busse, and orderly officer Pepo Specht. Dazzled by the bombardment, Specht remarked, “Fantastic fireworks!” Busse nodded, but added, “I’m not sure we’ll punch sufficiently large holes into those fortifications.”

As dawn painted the sky red on June 7, the German artillery fire built up to a raging tempest. Southward from the cover of the Belbek Valley, roughly from Kamyshly to the Black Sea, the 54th Corps attacked with the 24th, 50th, 22nd and 132nd Infantry Divisions. The infantry charged through clouds of dust and smoke against the Soviet positions. Assault parties and sappers led the way, using shellholes as cover. Wire cutters and bangalore torpedoes cleared a path through the barbed wire. Facing them was General Laskin’s 172nd ID.

“Shells whined overhead and exploded on all sides,” Laskin wrote. “A whirlwind of fire was raging at all our positions. Enormous clods of earth and uprooted trees flew into the air. An enormous dark gray cloud of smoke and dust rose higher and higher and finally eclipsed the sun. In my sector, the Germans outnumbered us one to nine in manpower and one to ten in artillery, not to speak of tanks, because we had none.”

In spite of the furious German attack, Busse’s pessimism proved correct. Safe from within positions of solid rock, the Soviets unleashed their own artillery. “The Russian artillery and armored fortifications spring to life everywhere, the whole horizon is a tremendous gun-flash,” noted a disgusted Richthofen, who surveyed the battlefield from his Storch observation plane.

The German infantry attacked with its usual bravado, but the Soviets made them fight for every yard. After an optimistic start, the advance slowed to a snail’s pace.

An eyewitness recalled: “In a raging tempo the attack races down the slope, through the valley, and on to the other side, past minefields, through trip-wires and wire entanglements that were already cut by the engineers. Companies, platoons, and groups one after the other moved forward in the blue-gray powder smoke and thick dust. The going is slow through thick bushes. The Bolsheviks hide in their numberless holes, let us pass and then fall on us from the rear. Several times small and large infantry units are completely cut off. But the connection is always re-established, and then it isn’t so good for the sealed off Soviets.”

On the 8th, a weak Soviet counterattack by Colonel Potapov’s 79th Brigade was brushed aside, but no quick headway could be made into the Soviet positions. When the going got tough, the German infantry called on the Luftwaffe, but Richthofen was already pushing his men to their limits. Eighth Air Corps topped 1,000 carpet bombing sorties a day until shortages of fuel and bombs forced Richthofen to concentrate on column bombing high-priority targets.

“The screaming descent of the Stukas and the whistling of falling bombs seemed to make even nature hold her breath. The storming troops, exposed to the pitiless heat of the burning sun, paused for a few seconds, which must have seemed an eternity to the defenders. Yet our work at Sevastopol made the highest demands on men and material. Twelve, fourteen and even up to eighteen sorties were made daily by individual crews,” wrote Luftwaffe General Werner Baumbach.

German hand grenades and smoke canisters doggedly drove the Soviets from camouflaged firing pits. The feared German 88mm flak proved invaluable in cracking open pillboxes at point-blank range. Nevertheless, by June 12, the 22nd ID had just reached the spot where the previous winter offensive had ground to a halt. German casualties amounted to 10,300 in the first five days alone. If things did not pick up, Hitler threatened to turn the operation into a regular siege.

The Germans Start to Make Headway

To the dismay of the Soviets, German fortunes rapidly improved on June 13. Not only were there limited gains all along the north, but the super heavy siege guns blasted apart a turret on Fort Stalin. The German guns created craters 15 feet deep.

The 16th Infantry Regiment of the 22nd ID stormed the fort. Twice before–the previous December and four days earlier–Fort Stalin’s defenses had defied them. In one section an antitank gun scored a direct hit into a pillbox porthole and killed 30. The 10 remaining Communist party members used their comrades’ dead bodies as sandbags and fought on. Flamethrowers spewed fire accompanied by blasts of potato masher grenades, but the remaining Soviets held on until their political officer shot himself. When the last four Soviets crept out of the rubble, a severely wounded German soldier remarked, “It is not so bad, we have the Stalin fort.” During the battle, the 16th Infantry Regiment’s two attacking battalions lost all of their officers.

Through sweltering heat and a nightmarish scene, the Germans steadily pushed on. Black clouds of flies, smoke, and ash drifted over swaths of reeking, putrid corpses. At times the smoke and stench became so unbearable that both sides wore gas masks.

The Battle for Maxim Gorky

Ahead, the mighty 12-inch armored batteries of the modern Maxim Gorky, built in 1934, controlled the entire northern line. The 50-ton barrels fired over a range of 28 miles. On the 17th, a Stuka scored a direct hit and blew up the eastern turret. Salvos from 350mm German mortars took care of another gun. The 12-foot Röchlings shells they fired burrowed into concrete or rock before exploding. Gorky was wounded but not dead. The last of its four huge naval guns continued to belch destructive fire into the assaulting German infantry. The battle for the fortress would eclipse the contest for Fort Stalin.

It was the task of the 213th Infantry Regiment of the 73rd ID (part of Corps reserve) to deliver the deathblow to Gorky. The regimental commander, who had already distinguished himself at Kerch, led the charge at the head of his men. The right flank of the German regiment was stopped by a desperate Soviet counterattack, but the center and left flanks made ground. For three quarters of an hour, Stukas plastered the fortress with their bombs, followed by tremendous artillery shelling and a smoke screen. A gigantic cloud formed over the fortress upon which virtually all life was extinguished. German engineers gained the final 300 feet with little opposition and blew apart the last gun.

Gorky guns were silenced, but the fight for the fort was far from over. The 300-yard-long and 40-yard-wide concrete structure was three stories deep. The roof was three to four yards thick, and the walls two to three yards. The fort had its own underground water and power supplies, a field hospital, canteen, engineering shops, and various arsenals and battle stations.

It took two blasting operations to fracture the thick concrete. The Soviets answered demands for surrender by spitting forth fire from all slits and openings. Groups of Soviets even made sorties from ventilation shafts and secret exits.

Inside, the fight went from one hallway and room to the next. Steel doors were burst open and hand grenades hurled inside as sappers flattened themselves against the walls. The dissipating smoke revealed piles of Soviet dead. Ever so often, the pattern was interrupted by machine-gun fire. The Germans pressed closer and closer to the command center. According to Soviet sources, the Germans even resorted to drilling a hole into a steel door and pumping poison gas inside.

A battery commander led a group of men in a desperate escape attempt out of a sewer hole. Most of his men were killed and the rest marched into captivity. The remaining Soviet defenders were ordered to fight to the last man. Their last two messages sent to Sevastopol headquarters related:

“There are forty-six of us left. The Germans are hammering at our armored doors and calling on us to surrender. We have opened up the inspection hatch to fire twice on them.

“There are twenty-six of us left. We’re getting ready to blow ourselves up. Farewell. ”

Of 1,000 defenders, only 50 were taken prisoner. The numbers of German killed and wounded were equally high.

The fall of Maxim Gorky was indicative of German gains all along the northern line. To the east, the Saxons of the 31st Regiment, 24th ID, captured three forts, while the 22nd ID pushed southward from Fort Stalin. With the help of an assault-gun battalion, its 65th Infantry Regiment overcame Fort Siberia, while the 16th Infantry Regiment seized Forts Volga and Ural. Two days later, the 22nd Division was the first to reach Severnaya Bay.

To the south, the 30th Corps joined the attack on June 11. Ahead, on mountaintops and within ravines, the Soviets held a chain of concealed and fortified strongpoints. Behind these and halfway to the city loomed the even more formidable Sapun Heights.

The 72nd ID initiated the attack here. After heavy fighting the Germans took North Nose, Chapel Mountain, and Ruin Hill. A gap was opened for General Constatine Vasiliu-Racanu’s 1st Romanian MD, which in turn captured the Sugar Loaf position. The 170th Division, at first kept in reserve, took Kamary, and on the 18th its 72nd Reconnaissance Detachment won the Eagle Perch in front of the Sapun line. From there, it swung north to gain the Fedyukiny Heights. The 28th Light Division (LD) made slow progress over the rugged hills east of Balaclava, which had been in German possession since the previous autumn. The division’s soldiers faced tenacious opposition at Tadpole Hill, Cinnabar, Rose Hill, and the vineyards.

Back at the northern front, the entire fury of the German artillery and the Luftwaffe backed the 24th ID’s assaults on the peninsula forts at the entrance of Severnaya Bay, dominated by the old but still strong North Fort. To its left, the 22nd ID took hold of the cliffs above Severnaya Bay. Here the Soviets held out within deep supply galleries driven into the rock. At the first of them a Soviet commissar inside blew up the casemate, burying the occupants and killing a squad of German engineers. A German assault gun firing at point-blank range blew up other casemates. Crowds of exhausted soldiers and civilians emerged after their commissars committed suicide.

Meanwhile, the 50th ID advanced to the eastern end of Severnaya Bay, taking the heights of Gaytany. Its defenses ripped open by German assault guns, the Soviet 25th ID retreated toward the Inkerman station. To the left of the 50th ID, General Gheorghe Manoliu’s 4th Romanian MD and Radu Baldescu’s 18th Romanian ID fought through the wooded hills southeast of Gaytany. By the evening of the 27th, the Soviet 8th Marine Brigade was pushed from the Sakharnaya Golovka Hill.

Across the Severnaya Bay, the city and harbor endured relentless attacks by the Eighth Air Corps, whose high explosive and incendiary bombs hit buildings and batteries. Smoke clouds from the flaming city reached 5,000 feet into the air and stretched nearly a hundred miles. On June 24, Stukas pounced on a Soviet Aviation delegation gathered at Kruglyi Bay, killing 48 people, among them Soviet Major Generals F.G. Korobkov and N.A. Ostriakov.

The Germans Go After the Soviet’s Lifeblood: Its Naval Supply Line

The lifeblood of the hard-pressed Soviets was their naval supply line. In June, the Black Sea Fleet brought over 24,000 reinforcements and 15,000 tons of freight and evacuated 25,000 wounded. To provide such aid, the Soviet ships braved a harrowing Axis gauntlet. The wrath of the Luftwaffe precluded daylight landings, but at night, when in turn there was less danger from Soviet aircraft and warships, there was the peril of German and Italian motor torpedo boats (MTBs), armed motor boats, and Italian midget submarines. Air Command South greatly aided the Axis flotilla with reconnaissance, dropping flares, and strafing Soviet warships.

Oktyabrskii responded by ordering the aerial bombardment of the Axis naval base at Yalta. He also sent light warships to attack the port. On June 19, the worst of the Soviet attacks sank two midget submarines and severely damaged an MTB. But overall Axis naval losses were superficial and did little if anything to loosen the tightening Axis noose around the Soviet supply line.

The Abkhazia, a Russian luxury liner converted to a transport, went down in the harbor after her 16th sailing to Sevastopol. Dive- bombers sank the liner Georgia in view of the harbor. Her soldiers and sailors managed to swim ashore, but 500 tons of shells followed her to the bottom of the sea. On June 18, the Belostok was the last transport to arrive at Sevastopol. The next day she succumbed to German torpedo boats.

Soviet submarines, warships, and aircraft continued the hazardous missions of carrying men and supplies and paid the same price as the transport ships. The SCH-214 submarine was sunk on June 20. The destroyers Bezuprechny and Tashkent set off from Novorossiisk on June 26. The Bezuprechny fell victim to dive-bombers, but the Tashkent repelled air attacks and evaded torpedo boats to reach Sevastopol. Surviving more than 40 supply runs and 96 air attacks, she was the last warship to reach Sevastopol harbor.

The Tashkent took in over 2,000 wounded and refugees before braving her last voyage back to Novorossiisk on the night of June 27. For four hours she fought off German dive-bombers, shooting down two enemy planes. Her hull severely damaged, the destroyer was escorted to the safety of the harbor by rescue ships. Sadly, four days later the gallant Tashkent was sunk in the harbor by a Stuka raid.

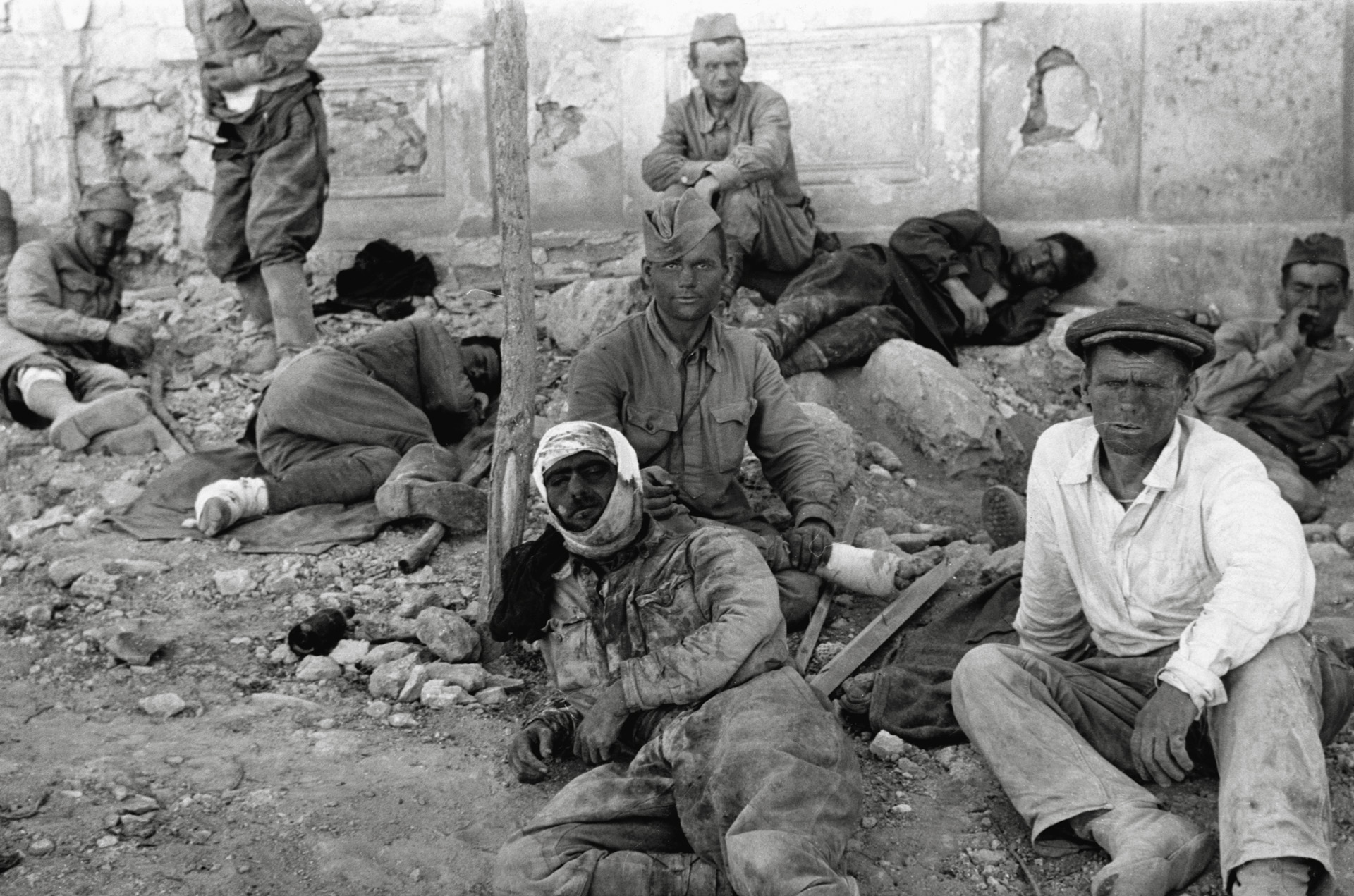

The attrition of Soviet supplies caused a rapid depletion of ammunition stockpiles. The local armaments industry could not meet the demands of the troops. Unable to sustain fire, Soviet soldiers fought the attacking Germans with bayonet charges. In a desperate attempt to rectify the situation, Soviet divers braved a rain of German bombardment to recover 39 tons of ammunition from the Georgia.

By June 26, the Eleventh Army had overrun virtually the entire outer ring of Sevastopol’s defenses. The 54th Corps faced the Bay of Severnaya and the honeycombed cliffs that rose from its southern shore. Running south from the inland end of the bay were the Inkerman Heights, site of another old but sturdy fort, and the 30th Corps’ main obstacle, the Sapun Heights.

Manstein’s Brazen Plan to Attack Across Severnaya Bay

Manstein came up with a brazen plan to have the 54th Corps attack straight across Severnaya Bay. His subordinate commanders shook their heads in disbelief: How could assault boats get across the bay in face of enemy fire with the soldiers fighting their way up ravines that were the only exits from the shore?

Manstein conceded that ideally the weight of the offensive would be switched to the 30th Corps in the south. This would take days for the troops and weeks for the heavy artillery. Manstein, who spent nearly all his days visiting officers from corps to battalion level as well as observation posts, was well aware that his worn-out soldiers would welcome any such respite. Many regiments were down to a few hundred men each. He recalled one company pulled out of line with but one officer and eight men remaining.

However, any cessation in the attack would give the enemy time to recoup. Furthermore, with Operation Blue imminently on the way, the Supreme Command planned for the withdrawal of the Eighth Air Corps from the Crimea. The latter had already undergone a change of command. A reluctant Richthofen was ordered to leave for Kursk to prepare future headquarters for the Eighth Air Corps; his place at Sevastopol taken by a colonel. There was thus no time to waste. The Eleventh Army would press on without hesitation.

On June 28, the 54th Corps resumed the offensive with the 50th ID storming the Inkerman position. The cliffs above the old fort held vast caverns with ammunition dumps and thousands of refugees and wounded soldiers. Suddenly, the ground shook as from an earthquake. To prevent the ammo from falling into Germans hands, fanatical commissars had blown up the caverns and condemned themselves and everyone inside to death.

During the night of the 28th, tension gripped the assault crews who prepared for their crossing of Severnaya Bay. To divert Soviet forces away from the bay, Italian MTBs and Army assault boats carried out a feigned landing near Cape Feolent that completely fooled the Soviets. The Eighth Air Corps pounded the city relentlessly to dampen any noise on the northern shore. The German artillery stood ready to unleash its fire onto the southern shore the moment the Russians perceived that they were under attack.

At one o’clock in the morning, under cover of darkness and a thick smoke screen, the first wave grenadiers of the 22nd and 24th IDs pushed their boats into the water and raced across the 1,000 yards of Severnaya Bay. Not a shot was fired until the Germans reached the enemy shore, jumped out of their boats, and greeted the surprised Soviets of the 79th Infantry Brigade with their MP-40 submachine guns. Flashes of retaliatory Soviet guns lit up the whole of the southern cliffs. The German artillery retorted from the northern shore, minimizing the losses sustained by subsequent assault waves.

As dawn rose above the horizon, the 30th Corps’ artillery fire and the long-range battery from the 54th Corps peppered the enemy defenses on the Sapun Heights. The bombardment gave the impression of an imminent attack along the entire front. Instead, the 170th ID struck into a limited area from the Fedjukiny Heights. The division penetrated the enemy defenses supported by the 300th Panzer Battalion’s Goliath tanks, direct fire from a flak regiment, and Stugs.

In the wake of the 170th ID, the 28th Light Division and 72nd ID were funneled into the ruptured enemy line. “After the successful crossing of the bay, the fall of the Heights of Inkerman and the 30th Corps breakthrough of the Sapun positions, the fate of Sevastopol was sealed,” Manstein noted of German progress by the 29th.

Having gained a foothold on the cliffs above the bay on the previous day, the 54th Corps secured Fort Malakhov from the remnants of the Soviet 79th Brigade and pierced the city’s last ring of defenses. Around the same time, the 72nd ID drove the Soviets from the Sapun positions. Although Petrov threw in what remained of the Soviet 25th ID, the 9th Marine and the 142nd Infantry Brigades to aid the defending 386th ID, they were unable to halt the German advance. In an adjacent sector, the 8th Brigade was virtually annihilated.

The 28th LD fought for the Soviet battery at the English Cemetery. Here a morbid battle raged amid the ruined marble monuments of the Crimean War. New cadavers joined the dead of the older war, whose graves were torn open by shelling. The 72nd ID meanwhile thrust along the south coast, taking Windmill Hill and the main road into the city. The 4th Romanian MD followed up the success by seizing the positions of Balaclava from the rear and bagging 10,000 prisoners.

All of the Soviet defensive rings were shattered and the ruined city remained in the hands of broken units. Since the battle began, the Luftwaffe had dumped several million propaganda leaflets on the defenders asking them to surrender. But the ill-supplied and starving Soviet soldiers refused to give up. Indeed, with nowhere to retreat and the bleak prospect of German imprisonment, they had little other choice. Manstein knew they would make the Germans pay in blood for every block and for every house. To avoid adding to the already high German casualties, he planned to smother the city with massive artillery and air barrages until the Soviets were simply incapable of resistance.

The Soviets Finally Evacuate Sevastopol

On June 30, flak guns, artillery, bombers, and fighters pounded the city mercilessly. The fatigued Luftwaffe ground and aircrews managed another 1,218 sorties, dropping 1,192 tons of bombs. Crowds of citizens fled to the west through rubble, flames, and clouds of black smoke to huddle in caves and await transport and possible salvation from the doomed Crimea. Stavka had decided to evacuate Sevastopol. The same night, Oktyabrskii, Petrov, and other senior officials fled the city by submarine. Petrov went reluctantly and had to be talked out of a suicide attempt.

Major General Vasily Novikov was left to attempt some sort of rear-guard action. He gathered what infantry units he could. The city was lost and tens of thousands of civilians and wounded soldiers streamed to the beaches of the Khersones Peninsula, where a Soviet battery remained. Novikov tried to establish a defensive line across the peninsula. He did his best, but the end was only a matter of time. The German artillery and Luftwaffe raged over the whole area, pounding the Soviet positions on the Khersones. It was too much. It had gone on too long.

Many of the defenders finally cracked. “They ran with maddened eyes, with tunics torn and flopping; panic-stricken, bewildered, miserable, frightened people. They seized feverishly any kind of craft they could—rafts, rubber floats, automobile tires—and flung themselves into the sea,” wrote one observer.

There was no attempt by the Black Sea Fleet to rescue the hapless civilians and troops trapped on Cape Khersones. The fleet was simply too devastated from the losses incurred in recent weeks to risk attacks by the Axis flotilla, Luftwaffe, or by the German heavy guns that now swept the area with impunity. On July 2, German bombers even raided the fleet’s Caucasian bases, badly damaging many large vessels. The only succor to the stranded on the cape were the heroic efforts of fishing boats and other small vessels who rescued a small number of people at night.

The inactivity of the Black Sea Fleet remained a point of contention for Petrov. In no kind words, he let Oktyabrskii know that many defenders were abandoned due to the Black Sea Fleet’s poor organization. As a result, Petrov’s name was left out of Oktyabrskii’s speeches and writings about the heroic defense of Sevastopol. Likewise, there was little mention of those forsaken to the Germans.

On July 1, after 249 days of siege, the Germans finally took what remained of Sevastopol. Elsewhere, the fighting continued. The 72nd ID captured Maxim Gorki II at Cape Feolent on the southern coast. The rest of the German divisions pushed on to Cape Khersones where Novikov held out for several more days until he ran out of rations and ammo. Desperate mobs of Soviets tried to break out. Arms linked, the women and girls of the Communist Youth leading them on, they marched into the deadly hail of awaiting MG-42 machine guns.

Those that fought on made their last stand in the caverns on the cape’s shore. Victor Gurin, sergeant 2nd class, lived to tell about it: “There were thousands of corpses lying on the shore and in the water. German snipers sneaked to a position of advantage near our burnt lorries and were killing off our officers by accurate shots. During July 2 we were still clinging to the narrow strip of the shore and fighting on. We beat off ten attacks that day.”

Thirty thousand Soviets surrendered on July 4, for a total of 90,000 prisoners, 467 guns, 758 mortars, and 155 antitank guns captured. Two more Soviet armies were smashed and an estimated 50,000 of the enemy killed on the battlefield. Including civilians, Soviet casualties were about 250,000 for the entire siege. Of the pitiful 30,000 civilians left at the end of the siege, two-thirds faced deportation or execution. Resistance did not fully peter out in the Khersones until July 9.

Scattered groups of soldiers escaped to the mountains from whence they continued guerrilla operations against the invaders. It was over. Not long afterward, a radio message arrived from a delighted Hitler, congratulating Manstein on his victory and promoting him to field marshal. His soldiers’ valor was honored with a special Crimean shield, worn on the upper left arm of the Crimean veterans’ uniforms.

A Costly Win for the Germans

Despite Manstein’s efforts to spare his infantry and crush the defenders with overwhelming bombardment, official Eleventh Army losses numbered 4,337 dead, 1,591 missing, and 18,183 wounded. Actual casualties were probably much higher, up to 75,000. In addition, they had used up 46,700 tons of munitions and 20,000 tons of bombs. In one month the Eighth Air Corps dropped more bombs on Sevastopol than the Luftwaffe dropped on Britain during entire air war of 1941.

The Soviets were finally driven from the Crimea. The battered Black Sea Fleet was no longer a threat to Axis operations in the area and was forced to operate from lesser bases along the Caucasus coast. Nullified as well was the danger of Soviet air attacks on Romanian oilfields from the Crimea. As a political repercussion, Axis control of the Black Sea compelled Turkey to think twice before joining the Allies.

The Eleventh Army was now in a perfect position to join the offensive against the Caucasus by crossing the straits of Kerch to the Kuban. From there it could intercept enemy forces retreating toward the Caucasus from the lower Don Basin before the advance of German Army Group A or, at the very least, serve as a reserve force. It was not to be. To Manstein’s vexation, the Eleventh Army was ordered northward to a threatened sector around Leningrad. Who knows how the Battle of Stalingrad might have ended if Manstein and his veteran army had stayed in the southern theater of operations?

If the Germans rightly considered the taking of Sevastopol a heroic feat of their infantry, so too the Soviets justifiably glorified their defense. Fifty thousand medals were awarded to the men and women of the Soviet Army and Navy, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the citizens who defended the city.

Russian propaganda turned the loss of Sevastopol into a great moral victory and claimed 300,000 Germans killed. Sevastopol became one of the four hero cities of the Soviet Union, alongside Odessa, Leningrad, and Stalingrad. The city remained under German occupation until liberated by the Soviets on May 9, 1944, with twice the number of artillery pieces used by the Germans in 1942.

Author Ludwig Dyck resides in Richmond, British Columbia. He has conducted extensive research on the Eastern Front of World War II and written several articles on the subject.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments