By Christopher Miskimon

First Lieutenant James H. Fields, a 24-year-old from Houston, Texas, led the 1st Platoon of Company A, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion. The 10th fell under the 4th Armored Division in General George Patton’s U.S. Third Army. For weeks in the late summer of 1944, Fields and his men chased retreating German troops across France toward the German border.

Now that border lay close by, and it seemed the Germans were not willing to flee across it just yet. The enemy still had some fight left in them; meanwhile, the American division had been forced to a halt due to fuel shortages. The Germans took advantage of the lull and counterattacked, hoping to prevent the advancing Americans from getting across the frontier into German territory. As the 4th Armored sought to stabilize its lines, refit for further action, and resume the attack, persistent German assaults continued.

On the night of September 26, 1944, Fields received orders to dig in as part of a new defensive line. He took his platoon to a gently sloping hill near the French town of Rechicourt. Moving at night always meant a risk of blundering into the enemy, but the move had to be completed. The battalion could afford no holes in its line; the Germans were expert at infiltration and would take advantage of any gap they found. First Platoon moved out cautiously through the night. Soon, Fields had his choice of position made for him. Ahead in the dark, voices could be heard, and they were speaking German. To press farther meant an unacceptable risk of a meeting engagement at night with an unpredictable outcome. The young lieutenant told his men to dig in where they were. The fight would come soon enough.

By late September 1944, a series of engagements around Arracourt finally ended in a stiff defeat for the German Army. These actions were among the few large-scale tank battles in Western Europe during the last nine months of World War II. The Battle of Arracourt occurred due to American fuel shortages and a German miscalculation mixed with a healthy dose of desperation. In early September, Third Army ran out of gasoline. Its headlong pursuit of the defeated Germans retreating from Normandy came to a sudden stop. Allied logisticians were simply unable to keep it supplied with enough fuel to maintain the advance.

Available fuel and delivery vehicles were mainly diverted to British forces to the north under Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, in part due to the forthcoming Market Garden offensive in the Netherlands. While Third Army paused to gather the fuel needed to resume the offensive, the Germans decided to strike. Hitler wanted to conduct an “offensive from the move,” a term that really meant counterattacking while retreating.

When the Third Army stopped, the Germans mistakenly assumed that the Americans were preparing for a major attack to pierce the German border. They were unaware of their enemy’s fuel shortages; many German generals considered Patton the best Allied general and could not conceive the Allied high command would deny Patton needed supplies in favor of Montgomery.

Since they assumed the American pause was only to stockpile supplies for the next advance, the Germans decided to mount a spoiling attack against Third Army. This led to the Arracourt engagements and a major defeat for Germany. Despite new, powerful armored vehicles such as the PzKpfw. V Panther medium tank, German armored forces were no longer the juggernaut that had rampaged across France in 1940. While the Germans consolidated their shattered tank units, the Americans formed a defensive line until they could resume their offensive.

The terrain around Arracourt consisted of farmland, mostly flat but with some small hills dotting the area. Small towns and villages sat between the sprawling farms along with a few wooded areas. The American centered their defense on the hills, mainly a short line of them extending from Bezange past Rechicourt and ending at Hill 318. By late September, the weather turned rainy for days on end, with fog appearing most mornings. This turned the surrounding fields into small seas of mud—tough going for men and vehicles alike. Significantly, the poor weather also frequently prevented the Americans from receiving air support.

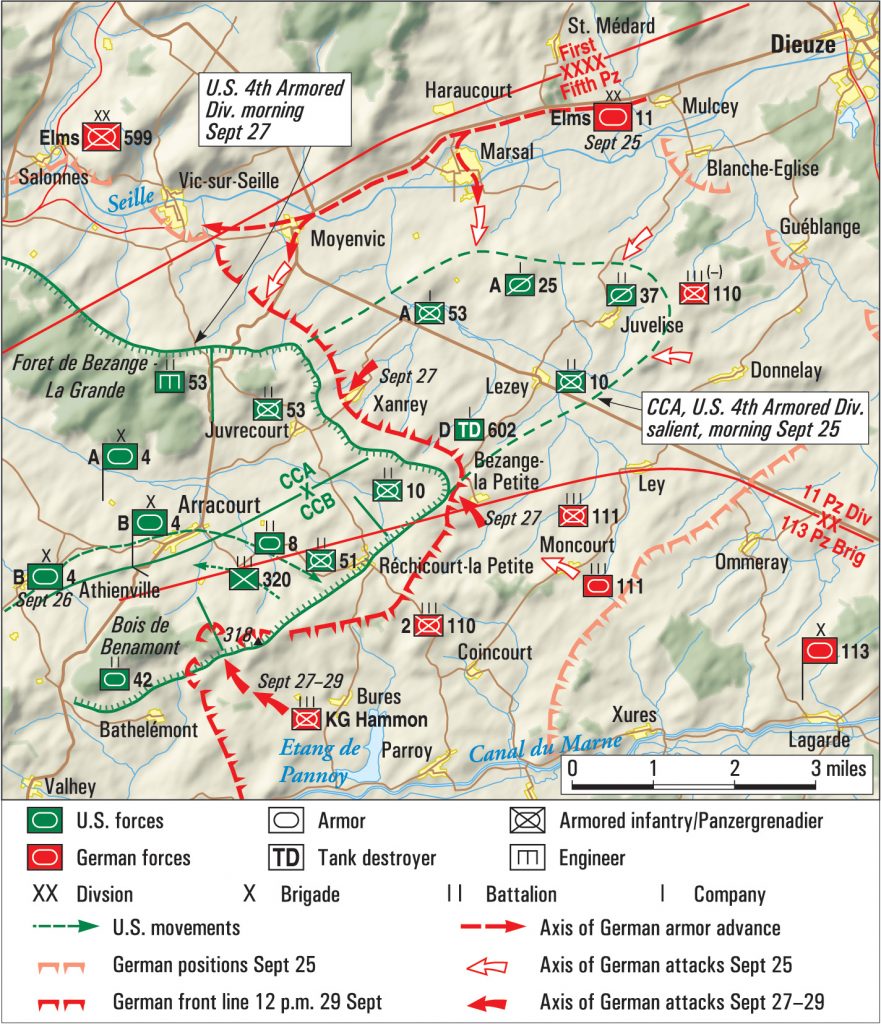

As the 4th Armored Division’s Combat Commands A and B dug in east of Arracourt around the village of Juvelize on September 24-25, 1944, German units from the veteran 11th Panzer Division readied their attack. A month earlier, the 11th Panzer Division had fought in southern France as part of Army Group G when Operation Dragoon, the Allied landings, occurred on August 15, 1944. When Army Group G retreated north toward Germany, the division provided security, conducting a skillful rearguard action. Though they arrived too late to take part in the Arracourt fighting, the unit, now assigned to Fifth Panzer Army, was in place to continue the attack against the consolidating U.S. 4th Armored Division.

The 11th Panzer Division had lost almost all its tanks during the long retreat, but the unit’s infantry had suffered relatively few losses, and it still had most of the halftracks and trucks for its four panzergrenadier (motorized infantry) battalions. The 11th Panzer also assumed operational control of the remnants of Panzer Brigade 113, a tank-and-infantry unit that had suffered heavily in the previous fighting around Arracourt.

Fifth Panzer Army assigned the 11th Panzer Division the task of eliminating the American salient around Arracourt. The survivors of the 113th joined Panzergrenadier Regiments 110 and 111 in a wooded area southeast of the salient and a second area just north of it. During the morning of September 24, while the panzer division moved into place, the neighboring 559th Volksgrenadier Division attacked the 4th Armored’s Combat Command B. The assault began with a heavy artillery bombardment at 8:30 am, followed by two battalions of infantry supported by about 30 panzers.

Due to heavy cloud cover, the Americans used artillery to blunt the German attack. However, at 10:00 am two squadrons of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers found a hole in the clouds and dove on the attacking Volksgrenadiers. Planes roared in as low as 15 feet above the ground and made skip-bombing attacks on the panzers. Afterward, they circled around to make strafing runs. After 15 minutes the surviving Germans retreated as the Americans gathered 194 prisoners. Total German losses amounted to an estimated 300 killed, 500 wounded, and 21 tanks lost. General Patton recommended a Medal of Honor for the pilot who led the strike.

German army-group command ordered renewed attacks for the 26th. German reconnaissance discovered an unoccupied crossroads town named Moyenvic, so that became the first objective. The Germans were unaware that American forces had abandoned the town the day before as part of a consolidation of their lines. Moyenvic fell so quickly and easily that the area commander, General Hasso von Manteuffel, ordered his troops to continue their advance. Attacks went in all along the salient, most of them no more than a battalion of infantry with a few tanks, but they were all repulsed.

Steady rain interfered with the Germans again on the 25th, hampering their attacks as the Americans attempted to pull back to their new lines. To facilitate the withdrawal, Colonel Bruce Clarke of Combat Command A staged an “Orson Welles Attack,” a reference to the famous hoax War of the Worlds radio broadcast of 1938. His headquarters aired false radio transmissions, many of them uncoded, to convey the idea that a large American counterattack was about to occur. Several companies of tanks from the 37th Tank Battalion made intentionally noisy movements to reinforce the subterfuge. This allowed the Americans freedom to withdraw to their new lines, which were shorter and more easily defended.

For the 4th Armored Division, this meant creating a line around the town of Arracourt, site of their recent victory. Its perimeter formed a small salient in the German lines with the division’s three armored infantry battalions—the 10th, 51st, and 53rd—pushed out several thousand yards from the town. To the northeast the 53rd dug in between an engineer unit on its left and the division’s cavalry reconnaissance squadron on its right. Next to the cavalry the 10th formed a curving line that turned near the village of Bezange-la-Petite and ended at Rechicourt-la-Petite to the southeast. The 51st took up the line on the 10th’s right along the rise known as Hill 318.

The 8th and 35th Tank Battalions took up positions behind the infantry, ready to react to enemy movements. The 4th Armored’s other tank battalion, the 37th under Lt. Col. Creighton Abrams, battered in earlier fighting, withdrew for rest and reconstitution. American armored divisions lacked enough infantry to form good defensive lines, so the Americans had to do their best, reinforced by the armor from the tank battalions. The original salient extended farther, but the GIs were pulled back over the course of September 24-25 to shorten their lines into a more defensible disposition. Even with the shortened lines, there were gaps that had to be monitored by frequent patrols.

On September 26, as 4th Armored attempted to finish reorganizing its units, a German column of halftracks, tanks, and armored cars appeared. With the GIs still not fully consolidated, forward observers used artillery to break up the attack. The German column fell back before it could even get organized, losing eight armored vehicles. The heaviest German assault came against the 10th Armored Infantry in the hills overlooking Bezange-la-Petite. Panzers with infantry support tried to force the Americans from the hills, intending to occupy the high ground.

B Company’s command post had to move after being hit by intense enemy artillery fire. German infantry tried to flank the American positions, but artillery pummeled them while U.S. tank destroyers struck at both panzers and enemy infantry alike. The rainy weather made it even harder for both sides. Still, fighting lasted the entire day, ending only after dusk when even the German artillery ceased firing. Panzergrenadiers kept trying to infiltrate the 10th’s positions for the rest of the night.

Wednesday, September 27, dawned with clearer weather. The thick mud slowly started drying, and at 10:00 am the panzergrenadiers began the day’s action. The mud still proved a hindrance to vehicles, so their halftracks stayed behind. Manteuffel wanted the hills captured, since they overlooked German positions to the south. He ordered 11th Panzer’s commander, Generalleutnant Wend von Wietersheim, to form another kampfgruppe (battle group) to join the attack. Wietersheim organized the remnants of Panzer Brigade 113 and the division’s reconnaissance battalion into Kampfgruppe Hammon and deployed them against Hill 318, occupied by C Company, 51st Armored Infantry.

Supported by the 2nd Battalion of Panzergrenadier Regiment 110, Kampfgruppe Hammon infiltrated through a farm at the base of the hill and soon reached the summit. Artillery fire crashed down on the Americans. Combined with the bad weather and mounting exhaustion, the GIs’ morale began to wane; the battalion reported 17 battle fatigue cases that day. Yet the Americans stayed in their foxholes and fought back, stopping the Germans. The crest of Hill 318 remained the focus of the fighting for the next few days. At 1:15 pm the Americans spotted a rare occurrence: a trio of German planes overhead. Appearances by Luftwaffe aircraft were quite rare by that time, but the GIs on Hill 318 did not hesitate to fire at them with every small arm they had. German attacks continued overnight, leading to short, sharp duels with hand grenades and machine guns.

Two thousand yards east, the 10th Armored Infantry had its own problems. Panzergrenadier Regiment 111 occupied Bezange-la-Petite below the American positions on Hill 265, overlooked by C Company. Farther west near Rechicourt, the enemy focused on A Company’s position. The company was badly understrength; its 3rd Platoon had only 15 men left. It seemed 1st Platoon would suffer the same level of attrition when a large force of panzergrenadiers attacked. Machine-gun and artillery fire lashed the Americans, pinning down most of them in the foxholes their leader, 1st Lt. James Fields, had told them to dig the night before.

As the incoming fire flashed above his head, Fields told his platoon’s medic to stay down. Despite this, when the medic heard a nearby GI call out for help, he got up and went. Within seconds bullets struck the medic, leaving him gravely wounded. The officer crawled from his slit trench to help the stricken medic, but he was dead. As Fields crawled back to his trench, a shell exploded nearby, raising a huge gout of muddy earth into the air. A fragment from that shell hit Fields in the side of his face. It tore through his teeth, gums and nasal passage, leaving him unable to speak. He could have easily and justifiably chosen to evacuate for treatment; no one would have blamed him. Instead, he stuffed gauze into this mouth to control the bleeding and stayed to lead his platoon. Fields used written notes and hand signals to give orders.

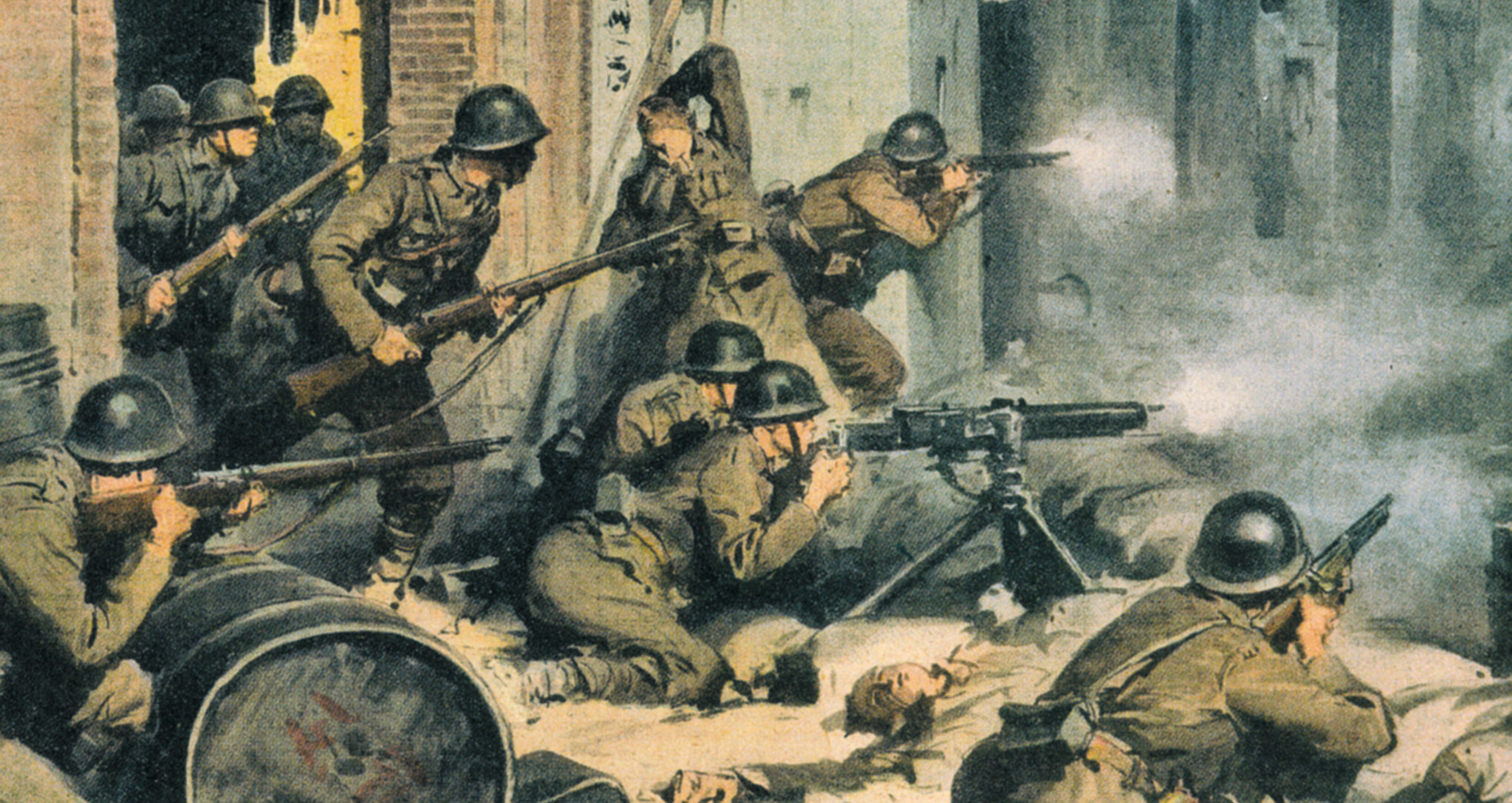

Soon afterward, a pair of German machine guns caught Fields’ platoon in a crossfire. Once again, he got out of his slit trench and ran to a nearby .30-caliber machine gun, its crew killed or wounded earlier in the battle. Taking up the 31-pound weapon, he held it at his hip and started firing bursts at each enemy machine gun. The weapon chattered as dozens of bullets flew at the Germans. Empty brass cartridge cases ejected from the weapon, piling at the young lieutenant’s feet.

Firing from the hip is not generally the most accurate way to use a machine gun, but Fields wielded his with such precision that both German weapons were soon silenced. His men were so impressed by this display of bravery they joined him, even though it exposed them to more enemy fire. The GIs grabbed more machine guns and even a few bazookas and laid into the attacking Germans. This combined fire finally broke the panzergrenadiers, who fell back scattered in disarray.

With his position at least temporarily secure, Fields finally consented to be evacuated. Taken to the battalion command post, Fields refused to leave until he explained the disposition of his soldiers. Using paper and pencil, he sketched a diagram showing where his men were along with those enemy positions he could locate. Only then did he let the aid men take him for treatment. Lieutenant Wilson from C Company transferred to take his place.

Fields’ bravery earned him a Medal of Honor, the first awarded to a soldier in Third Army. Patton later mentioned Fields in his autobiography, War As I Knew It, stating he did not want Fields returned to the front since he believed men awarded the Medal of Honor or Distinguished Service Cross would attempt to replicate their acts of bravery and get killed. With typical Patton style, the general added, “In order to produce a virile race, such men should be kept alive.”

The battle continued after Fields’ evacuation. A panzer rolled up to 1st Platoon’s foxholes and fired round after round, trying to blast the Americans out of their defenses. The GIs responded with rifle and machine-gun fire, killing the tank’s commander when he rose from his hatch. The hail of bullets also forced the rest of the German crew to close their own hatches and killed or wounded all the panzergrenadiers accompanying the enemy tank on its sortie.

With their infantry support lost, the German tankers retreated to a safer distance, found a defilade, and continued shelling the Americans. Nearby, a few U.S. tank destroyers sheltered with C Company, but heavy tank and artillery fire kept them pinned, and the crews refused to move to A Company’s position and engage the panzer, which pummeled 1st Platoon until it was forced to withdraw to new positions closer to Rechicourt.

The situation became so precarious the A Company commander, Captain Thomas J. McDonald, decided to contract his perimeter to make it more manageable. It proved a sensible decision. His company’s original positions were under observation by German forward observers, who continually called down heavy artillery fire. The day’s fighting also knocked out all the radios and field telephones, leaving McDonald unable to reach his battalion headquarters. Things were made worse by the loss of all their medics, leaving no one to properly tend the many wounded. In all, A Company lost almost half its strength in less than two days of fighting, starting the battle with 224 men and ending with 116.

The northern side of the American salient, manned by the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, fared better on September 27. They repelled a German night attack with little trouble, but at 10:00 am the 1st Battalion of Panzergrenadier Regiment 110 attacked from behind the village of Xanrey, directly in front of A Company, 53rd. The Germans advanced steadily for about 1,800 yards but ran into an artillery barrage from six battalions of guns assigned to support Combat Command A. The intense bombardment stopped the panzergrenadiers cold; the infantrymen retreated in disorder back to Xanrey, covered by their supporting panzers.

The GIs watched as their opponents took cover in the small village, and it occurred to them Xanrey made a good jumping off point for further enemy attacks—too good, in fact, to remain standing. The 35th Tank Battalion of Combat Command A formed a task force from several tank companies with two platoons of infantry for support. The GIs intended to “burn Xanrey to the ground.”

The raid went in during the early afternoon. M4 Sherman medium tanks charged past the village and then turned right into it, firing as they went. They quickly overwhelmed the defenders and blasted the buildings with cannon fire. The tanks’ coaxial and bow machine guns cut down German troops as they fled eastward from Xanrey. The infantry followed close behind and cleared the town while two platoons of tank destroyers covered them from the hills. The task force commander, Lt. Col. Oden, estimated 135 German troops lay dead in the village before the Americans withdrew to their starting point near the village of Juvrecourt behind the 53rd’s foxholes. The 35th lost two tanks to mines during the attack.

The 11th Panzer plan for September 28 was simple and came straight from General Manteuffel. The Germans were to take the hills along the southern side of the salient and break through to Arracourt. The Americans had plans of their own, however, and a dawn counterattack by the 51st Armored Infantry retook the crest of Hill 318. Kampfgruppe Hammon retreated at first but launched its own counterstrike and retook the hilltop soon after, using the remains of some old World War I-era trenches as cover to move up. The GIs dug in on the reverse slope and fended off three more attacks throughout the morning, finally regaining the crest about noon.

The weather cleared as well, allowing American airpower to reappear over the battlefield. Squadrons of P-47s launched strikes on the German-held ground south of Hill 318, making 107 sorties. The German were using the village of Bures, some 1,500 yards south of the hill, as a staging area. The American fighter-bombers flattened the town with bombs and rockets, strafing any concentration of troops they saw. These air attacks badly disrupted German efforts to reinforce their men on Hill 318, who also suffered a lack of artillery support that day. The batteries had to move overnight to new positions, and the forward observers did not arrive until late on the 28th.

Late in the afternoon, the Germans launched yet another assault, but the American artillery blasted the attack well short of its goal. After dark a combined force of panzergrenadiers and panzers took the southern side of the hill, forcing the Americans over the crest onto the northern side of Hill 318, where they were promptly hit with a bombardment by newly placed German batteries. In response, 4th Armored Division massed four battalions of guns and pounded the entire southern slope of the hill, following with an attack by the 51st. The GIs occupied the south side of Hill 318 by midnight and held against scattered attempts to retake it the rest of the night.

The 10th Armored Infantry suffered several attacks by the Germans as well that day. One German sortie forced one of A Company’s platoons to retreat, but this left the Germans vulnerable to artillery, which the Americans quickly called down, stopping their opponents cold. By now General Wietersheim could tell his men were on the brink of exhaustion and asked General Manteuffel to allow him to end the attacks and let his men rest. If not, Wietersheim feared the division would become ineffective.

Manteuffel, under pressure from the high command in Berlin to get results, refused. The day’s remaining attacks against the 10th Armored Infantry failed due both to the troops’ exhaustion and a lack of fire support. Most of 11th Panzer’s artillery was out of range. Efforts to use the division’s reconnaissance battalion and some of Kampfgruppe Hammon to reinforce these attacks bogged down for unknown reasons.

The Americans also suffered as more of their own tired troops succumbed to battle fatigue, mostly among the infantry on the front line. The combination of little sleep, no hot food, and bad weather took its toll. Despite these problems, the GIs held through the night as German patrols probed the line for weak spots. Help came from the 25th Cavalry, which sent their own patrols in front of the line to screen it from the Germans. The cavalrymen carried out reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance missions through the night. Meanwhile, the Germans also focused on bringing up reinforcements to help their battered units in the next day’s attacks.

By early morning September 29, those reinforcements assembled near the ruins of Bures. They included a battalion of panzergrenadiers, the divisional reconnaissance battalion, a company of combat engineers, and all the remaining armor from two shattered panzer brigades. The Germans managed to amass 20 Panther and 18 PzKpfw. IV tanks along with 11 Flakpanzer IV self-propelled antiaircraft guns in this sector, though it is unlikely all of them were operational. This force set out against Hill 318 before dawn. A thick fog settled over the area, limiting visibility to about 40 feet.

The men of the 51st Armored Infantry still sat atop the hill, listening to the sound of tank engines in the darkness. Not far behind them, the crews of the 8th Tank Battalion sat in their M-4s, struggling to stay dry and warm. Captain Eugene Bush of C Company said, “It sounded as if enemy armored vehicles were coming right into my area.” Ahead of him the Germans attacked the 51st, pushing it steadily back during several hours of fighting. By 10:15, the GIs had been pushed 500 yards back, and the Germans controlled the crest of Hill 318.

The GIs suffered heavy casualties, and soon the 8th received orders to send two companies forward to support the infantry. The tanks had trouble coordinating movement in the fog and mud, so the Combat Command B commander, Brig. Gen. Holmes Dager, ordered them not to move over the crest until the fog lifted. This became a moot point for A Company, whose tanks were stopped by heavy German fire.

When the tank and infantry commanders noticed the fog was not dispersing, they realized the Germans were using smoke generators to thicken the haze. A forward outpost also reported the enemy was moving forward in strength. When the fog finally lifted at 11:00 am, Captain Bush and C Company realized they were already on the crest. German mortar fire immediately started landing around them. In the open ground below the hill, Bush could see German tanks gathering for another attack. He requested air support.

Luckily, a tactical air liaison officer went with the tanks that morning. Trained in coordinating with pilots and directing air strikes, he called in squadrons of fighter-bombers to assist the beleaguered GIs. The first groups of planes to arrive had little effect. Diverted from a mission over the nearby city of Metz, the planes carried propaganda leaflets and had only their .50-caliber machine guns available. The next aircraft to arrive, from the 405th Fighter Group, carried rockets and bombs, which they used to critical effect, destroying several tanks before they could make their attack on Hill 318. The heavy bombing also forced a few German tanks out of some woods they were using for concealment. An American forward observer quickly called down artillery fire, destroying them.

Captain Bush watched the fighter-bombers do their work and later said, “The Air Corps really did the trick!” Still, he did not allow his tank crews to be mere spectators; C Company opened fire on the German armor at the base of Hill 318, adding to the mayhem. The company claimed six enemy tanks knocked out that day. The 51st estimated roughly 240 German dead littering Hill 318 and the fields below.

General Wietersheim described the furious action at Hill 318, adding a lament about the situation. “In a few minutes 18 of our tanks and several armored personnel carriers were burning! Our own infantry retreated, strangely enough not pursued by the enemy…. As a result, any chance of winning our objective had been frustrated. We had suffered losses that could have been prevented if only we had been satisfied with the line already gained which was suitable for the defense.”

To the east, renewed attacks against the 10th Armored Infantry focused on A and C Companies. After hours of fighting, the GIs fell back to the reverse slope of the hill but grimly held onto those positions until dusk. This combination of airpower and determination finally turned the tide. The German troops, exhausted, battered and demoralized, retreated in disarray. Some units simply fell apart. Many German soldiers began to fear the Americans would counterattack and trap them with their backs against the water of a canal to their rear.

Only four panzers remained operational, and the few surviving flakpanzers had no effect on the continuing air attacks. The German reconnaissance battalion commander, Major Karl Bode, had a nervous breakdown. A neighboring division had to set up a straggler line to gather all the fleeing panzergrenadiers, who were still being rounded up the next day. The report to General Manteuffel stated directly, “Hill triangle lost. Troops exhausted, need rest.” Further attacks against the Americans at Arracourt were cancelled at 11:00 that night.

The Battle of Arracourt was a costly defeat for the Germans, using resources they could not spare. The attacks during the last week of September were a continuation of that wastage, throwing away irreplaceable men and armored vehicles in a desperate attempt to regain the initiative. Several German commanders had recently arrived from the Eastern Front and were unaware of the Americans’ ability to mass airpower and artillery against enemy concentrations. They paid dearly for their experience.

The Americans, though suffering from combat exhaustion and a lack of fuel, used their advantages to maximum effect. Combined with the determination of the GIs in their foxholes, it proved decisive.

Author Christopher Miskimon served as an officer in the Colorado National Guard’s 157th Regiment and is a regular contributor to WWII History. He also writes the Books column.