By Marc D. Bernstein

On September 15, 1950, the United Nations X Corps, spearheaded by two regiments of the U.S. 1st Marine Division, landed at Inchon, on South Korea’s west coast, 25 miles from the capital of Seoul. The landing was a spectacular gamble by UN Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur and proved to be an equally spectacular success. Despite rampant rumors of an imminent landing circulating for weeks before the actual event, MacArthur’s Inchon assault completely surprised the North Koreans, whose army was largely engaged in attacking UN forces along the Pusan Perimeter, far to the south. Inchon proved to be only lightly defended by the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA), and the U.S. Marines rapidly established a beachhead. The battle for Inchon was quickly over. The next objective was Seoul itself. The capital would prove a much tougher nut to crack.

To Take Back Seoul

War had begun on the Korean Peninsula on June 25, 1950, when North Korean Russian-made T-34 tanks crashed across the 38th parallel and rapidly routed the defending Republic of Korea (ROK) forces. Within days, Seoul had fallen to the North Koreans and the bridges across the Han River had been blown by the retreating ROK Army. American President Harry Truman reacted immediately and forcefully to counter the naked Communist aggression, rushing the U.S. 24th Infantry Division to Korea from occupation duty in Japan to help stem the onrushing Communist tide. At the same time, the United Nations, with the Soviet Union absent in protest of Nationalist China’s presence on the Security Council, voted to enter the war on South Korea’s side.

Undeterred by international sanctions, the North Korean forces continued their drive southward, hemming in the UN forces around Pusan, in the extreme southeast of the country. MacArthur struck back with his audacious amphibious assault at Inchon. American Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey spoke for many when he described MacArthur’s counterattack as “characteristic and magnificent. The Inchon landing is the most masterly and audacious strategic stroke in all history.” Other military leaders called it nothing less than “a 20th century Cannae.” (In 216 bc, Carthaginian leader Hannibal inflicted Imperial Rome’s greatest defeat at Cannae, on the Adriatic coast.)

The surprise landing immediately threatened the North Koreans’ line of communication to the Pusan Perimeter, requiring a pullback of NKPA units from the south to avoid the risk of having them permanently cut off. The capital of Seoul was itself not initially occupied by many North Korean troops, but this would quickly change. As a result of the Inchon landing, the North Koreans sent reinforcements into the greater Seoul area, intending to make a determined stand in the capital. UN forces advancing from the seaport of Inchon would have to battle 20,000 NKPA troops tasked with holding Seoul. They would prove stout adversaries.

MacArthur reasoned that the recapture of Seoul was a crucial follow-up to the Inchon landing. “By seizing Seoul, I would completely paralyze the enemy’s supply system coming and going,” the general noted. “This in turn would paralyze the fighting power of the troops that now faced [Lt. Gen. Walton H.] Walker. Without munitions and food they would soon be helpless and disorganized, and could be easily overpowered by our smaller but well supplied forces.”

At the beginning of the war, Seoul had a population of nearly two million people. The city core was surrounded by hills, cottages, and rural villages, but the inner city contained modern office buildings that were solidly constructed and maintained. Wide thoroughfares crisscrossed the city. One major road, Ma Po Boulevard, was lined on both sides by two- and three-story stucco and masonry structures as well as churches, hospitals, and walled compounds. Seoul was a logistical hub for the North Korean invaders because the vast majority of their supplies were funneled through a fairly narrow corridor in and around the South Korean capital.

September 18: The Drive to Seoul Begins

X Corps, commanded by MacArthur’s erstwhile chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, began its drive from Inchon to Seoul on September 18. The 5th Marines, under Lt. Col. Raymond L. Murray, advanced on Kimpo Airfield, Seoul’s primary airport, and captured it with little difficulty. Kimpo lay some miles south of the Han River (Seoul is on the river’s north bank). Troops and supplies were flown into Kimpo while the Marines continued to advance cautiously eastward.

The newly arrived 7th Marines covered the 5th Marines’ northwestern flank between Seoul and Uijongbu, while the U.S. Army’s 31st Infantry, on the X Corps southeastern flank, advanced to make contact with Walker’s units moving up from the Pusan Perimeter. The 187th Airborne also landed at newly liberated Kimpo in late September to provide additional flank protection to the Marines south of the Han.

North Korean units called to defend Seoul included the green 18th Division, which initially had been heading to the Pusan Perimeter, and an experienced regiment of the 9th Division, which had been fighting along the perimeter’s Naktong River line. In addition, roughly 2,000 troops of the 78th Independent Infantry Regiment and the 25th Brigade moved into the Seoul area as rapidly as possible after the Inchon landing on express orders from North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung. Other Communist units in the Seoul area were the 70th Regiment, the 42nd Tank Regiment, and the 107th Security Regiment.

The 7th Marines were still en route to Inchon when Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith’s 1st and 5th Marines began their push from the seaport to the capital. Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller’s 1st Marines pressed forward along the Seoul-Inchon highway, heading directly for Yongdungpo. The 5th Marines, on Puller’s left, managed to fully secure Kimpo Airfield by September 19 in preparation for crossing the Han River to the west of Seoul. Opposition was light in the first days after the Inchon landing because the NKPA was still consolidating its units in the Seoul area. The Communist forces hoped to use natural obstacles such as the river and the hills ringing the city to retain control of the capital. The U.S. Army’s 7th Division had begun disembarking at Inchon on September 18, and South Korean units joined the campaign. They would all be needed, as NKPA resistance rapidly stiffened around Seoul.

On September 18, Almond ordered Smith to send his units across the Han and capture a hill position north of the capital. Smith issued his own order to his regiments. On the 19th, they were to secure a Han crossing site near Haengju, followed by a river crossing on the 20th and the capture of the Communists’ mountain fortress, Hill 125. At 8:40 on the evening of the 19th, a scouting party of 14 men from the 5th Marines’ Reconnaissance Company swam the river to locate a suitable crossing site for the regiment on the north bank. They landed safely at the Haengju ferry site and reconnoitered, finding no enemy in the immediate vicinity.

North Korean troops, in fact, were ensconced on Hill 125, and after amphibious tractors (LVTs) carrying the rest of the company were halfway across the river, heavy enemy fire crashed down on them, forcing them to retreat to the south bank. A daylight crossing of the river was now required. The Marines began a heavy predawn bombardment of Hill 125, followed by an assault crossing at 6:45 am led by I Company of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines. Within three hours, they secured Hill 125, and the rest of the 3rd Battalion crossed in LVTs without incident.

By nightfall, the 5th Marines, along with the 2nd Battalion of the ROK 1st Marine Regiment and an attached U.S. tank company, were on the north bank of the Han. The tanks had been ferried across by a combat engineer battalion using pontoon bridging. Hill 125 was just eight miles from downtown Seoul. The 5th Marines’ eastward advance continued, this time north of the river.

The Battle for Yongdungpo

Also on the morning of September 20, Puller’s 1st Marines closed on the Seoul suburb of Yongdungpo. The Marines repulsed a counterattack by five T-34s, and the NKPA 87th Regiment of the 18th Division lost 300 troops and several tanks. Puller’s forces moved directly along the highway and through hill country south of the Han. The Communists withdrew into Yongdungpo itself. Puller requested unrestricted fire support from Marine artillery and airplanes. Almond granted Puller’s request.

At 6:30 am on September 21, Puller launched his attack into Yongdungpo. Staff Sergeant Lee Bergee of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, recalled the assault. “Yongdungpo was surrounded by a moat on one side, by a wide rice paddy on the west, and by high ridges on the southeast,” said Bergee. “Staring at the sooty chimneys of the city, I wondered how many of us would be killed taking this dirty town. Yongdungpo was literally infested with North Korean troops. All afternoon we observed them fortifying their ridge. Artillery, heavy mortars, and our Corsairs pummeled Yongdungpo that afternoon. The 4.2s [mortars] fired white phosphorous, setting sections of the city ablaze. One of our planes dropped napalm on a block-long fuel dump. Flame and smoke rose a mile and a half into the air.”

The fight for Yongdungpo lasted two days before the commander of the NKPA’s 87th Regiment decided he’d had enough and quit the town. Puller’s Marines advanced to the south bank of the Han, directly opposite Seoul, and began concerning themselves with the mechanics of crossing the river in LVTs. The 5th Marines advanced from the west to cover their left flank.

Hill 296: A Battle of Fire Superiority

Murray’s 5th Marines, whose own left flank would be covered by Lt. Col. Homer L. Litzenberg’s newly arriving 7th Marines, commenced a week-long attack on Seoul from the west. NKPA defenders manned a main line of resistance anchored on Hill 296. The jumbled terrain around the hill was ideal defensive ground. During World War II, Japanese forces had used the same ridges for tactical training, and the North Koreans had the advantage of preexisting firing positions, command posts and observation sites. Colonel Chan Wil Ki of the 25th Brigade led a total force of nearly 10,000 troops in the hill sector west of Seoul, exceeding the combined U.S. and ROK Marine formations arrayed against him. For the Allies, going would be tough.

Murray began his assault of Hill 296 at 7 am on September 22, with the 3rd Battalion on the left, the 1st ROK Marine Battalion in the center, and the 1st Battalion on the right. The 2nd Battalion was in reserve. By evening, H Company had reached the crest of Hill 296, but the Communist forces continued to mount a defense in depth in the ravines south and east of the hill. The ROK Marines and Murray’s 1st Battalion had to advance across open ground. Close-air support from the Corsairs of Marine Aircraft Group 33 proved invaluable in beating down the NKPA defenders. Some pilots in Major Arnold A. Lund’s VMF-323 squadron, flying off the escort carrier Badoeng Strait, flew as many as four sorties a day per plane.

The battle for Hill 296 ultimately boiled down to fire superiority. Murray’s infantry could count on not only significant air support, but also great assistance from the artillery of the 11th Marines, which fired round after round throughout the night while the infantry battled forward with great difficulty. Eventually, Chan’s stout NKPA defenders crumbled under the strain.

Fight for the Western Ridge

By September 23, Smith’s 1st Marine Division had all three of its infantry regiments on the line, and Smith came under pressure from Almond to keep advancing into Seoul. September 25 would mark the three-month anniversary of the North Korean invasion, and General MacArthur wanted Seoul liberated by that date for symbolic purposes. Almond chafed at the painstaking progress of Smith’s division. Almond’s operations officer noted later, “The Marines were exasperatingly deliberate at a time when rapid maneuver was imperative.”

Smith disagreed with Almond’s assessment of the situation, understanding that the nature of Communist resistance had changed since the relatively light defense of Inchon. Almond decided to bring additional units into the battle for Seoul. He ordered the U.S. Army’s 7th Division’s 32nd Infantry, under the command of Colonel Charles E. Beauchamp, to move across the Han River in LVTs and attack Seoul from the southeast. The movement was scheduled to take place on the morning of September 25.

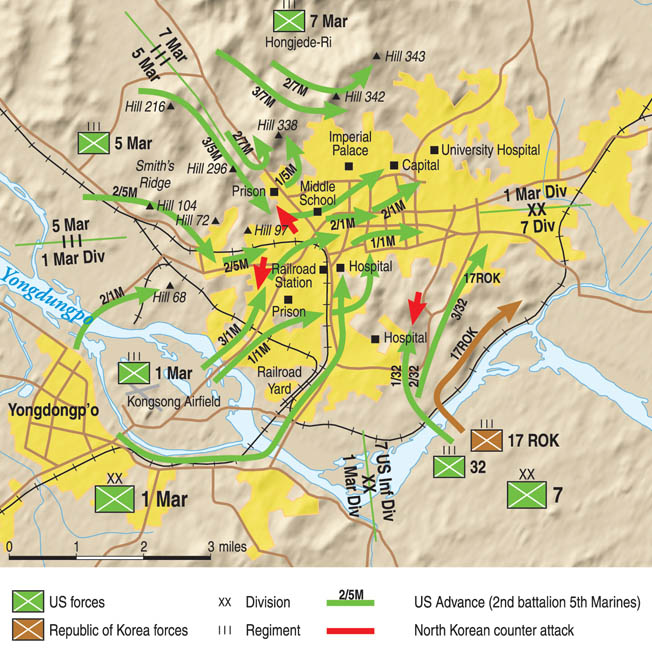

Smith’s own operational plan for taking the city called for Puller’s 1st Marines to cross the Han just west of Yongdungpo, move east along the north bank of the river, and fight their way into the center of Seoul. Murray’s 5th Marines would carry the enemy defenses in the hills west of Seoul and enter the northwestern part of the city, while Litzenberg’s 7th Marines provided flank protection to the north and cut the Seoul-Uijongbu highway to prevent a successful NKPA withdrawal. Seven battalions of artillery were available to support the tanks and infantry going into Seoul.

Before the plans could be put into effect, it was necessary to clear the North Koreans’ 25th Brigade, 78th Independent Regiment, and assorted units from the western ridges. The enemy brigade was an elite force with about 2,500 men and was composed of two infantry battalions, four heavy machine-gun battalions, an engineer battalion, a 76mm artillery battalion, a 120mm mortar battalion and miscellaneous service troops. Most of the officers and NCOs of the brigade had seen previous combat experience with Chinese Communist forces outside Korea. The 78th Regiment was also battle-tested.

September 24 marked the day of heaviest fighting for the western ridges. The key to the battle became the advance of 1st Lieutenant H.J. “Hog Jaw” Smith’s D Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, which had to attack over open ground and seize a strongly defended knoll, then continue the advance into a heavily wooded ridge. The NKPA actively defended the sector with more than 1,000 troops. Smith called in repeated air strikes and artillery fire, and eventually succeeded in taking the position, at the cost of his own life and 35 other Marines’ lives that day. Seizing the ridge cost the company 178 casualties of the 206 men who had advanced across the valley the previous day. The reverse slopes of the complex looked like a charnel house. The surviving Marines began to count the rows of NKPA bodies, most blasted hideously by Marine 105mm howitzers, Corsairs, and mortars. They reached 1,500 before they stopped counting.

Three Days of Hell

By dusk on September 25, Almond had his entire infantry force positioned north of the Han River for the recapture of Seoul. The 32nd Infantry had completed its crossing of the river by mid-afternoon on the 25th and quickly seized Nam-san, a 900-foot-high hill also known as South Mountain, which closely overlooked the southeastern districts of Seoul. Meanwhile, the ROK 17th Regiment covered the 32nd’s right flank and attacked Hill 348, five miles east of the capital. The 1st and 5th Marines had begun their own advance toward the center of Seoul that same morning. Each of the Marine regiments operating within Seoul itself would advance on a frontage of 11/2 miles, with specific objectives such as Government House and the embassies already identified.

The fight for possession of the South Korean capital city would prove to be three days of hell. The NKPA was determined to make a stand behind barricades every 300 to 400 yards along the major streets. They threw up barricades of rice bags filled with sand or rubble, eight feet wide by five feet high. Each barricade was defended by antitank guns and heavy machine guns, and the approach to each was strewn with mines. The defenders reinforced their positions with overturned trolley cars, automobiles, barrels, streetcar rails, and other debris. Interlocking fire from 45mm antitank guns, T-34 tanks, and self-propelled antitank rifles made the approaches virtual killing zones.

Along the outer edges of the barricades, Chan placed teams of snipers to disrupt Allied assaults. The snipers were skilled, furtive killers. Photojournalist David Douglas Duncan, attached to Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, vividly remembered the ambushers. “Reds, armed with rapid fire burp guns and hiding behind the gutter walls along the way, squirted quick bursts at the steadily pushing Marines, then melted away,” he wrote. Every building in Seoul seemed to house an enemy sniper. Marines dubbed one particularly dangerous intersection “Blood and Bones Corner.” Army Signal Corps Lieutenant Robert Strickland, attached to the Marines, felt the brunt of the North Korean defense. “The air was whipping with everything from flying stones to big antitank shells,” he recalled. “We got so much fire of all kinds that I lost count. I have seen a lot of men get hit in this war and in World War II, but I think I have never seen so many men get hit so fast in such a small area.”

Faced with such suicidal resistance, Puller’s 1st Marines could make only 2,000 yards of headway into Seoul on September 25, even while Almond was making a public statement declaring that the capital had been fully liberated at 2 pm. The Marines’ technique for reducing the NKPA defenses involved the extensive use of concentrated firepower. The Marines slowly ground forward under a hail of protecting artillery, mortar fire, and close air support that leveled whole acres of enemy territory.

The defenders fought with great tenacity to the end, firing from rooftops, trees and side streets. Intense heat from the burning buildings added to the nightmare, and Communist suicide squads repeatedly attacked American tanks. Robert Tallent of Company D, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines described the deadly close-in fighting. “In actions of this type there can be no flanking of a position—only so many men can get into the fight. The width of the street, available cover and strength of the enemy fire dictate the number of troops that can be brought to bear on any one position. The barricade is a separate battle all to itself.”

The Americans utilized M-26 Pershing and M4A3 Sherman tanks to hammer through the Communist barricades. The Pershing, supporting the Marines, used a 90mm main gun and two .30-caliber machine guns, while the Army-backed Sherman tanks featured 76mm main guns and three .30-caliber machine guns. Staff Sergeant Chester Bair of the Heavy Tank Company, 32nd Infantry Regiment, noted that “as soon as one [barricade] had been eliminated, there would be another. After a tank overran three or four of them, another one would replace it.” And journalist Duncan noted, “The tanks traded round for round with the heavily armed, barricaded enemy and chunks of armor and bits of barricade were blown high into the air.”

Horrific Collateral Damage

Withering firepower was brought to bear. As always in wartime, civilians on the scene suffered along with combatants. Reginald W. Thompson, a correspondent for the London Daily Telegraph, wrote that “few people can have suffered so terrible a liberation.” Thompson found the UN campaign “profoundly disturbing. The slightest resistance brought down a deluge of destruction blotting out the area.” Ironically, a New York Times reporter quoted Puller as telling his subordinates, “We’ve got plenty of ammunition and air support, and I want you to use it only when necessary.” Marine Captain A.B. Reynolds was not so sanguine. “This is a hell of a way to make a living, isn’t it?” he growled.

Despite his disavowal, Puller was in the forefront of those utilizing heavy firepower against the NKPA. By the end of the month, the city was 65 percent destroyed and thousands of South Korean civilians lay dead. MacArthur seemed far more interested in retaking the capital as quickly as possible rather than in keeping collateral damage to a minimum—a clear distinction from his more cautious approach to the recapture of Manila five years earlier in World War II. Unlike Manila, MacArthur had never lived in Seoul.

Almond, in particular, was severely criticized for his operational handling of the recapture of Seoul. Historian Robert Leckie, a Marine veteran himself, surmised that “Almond either rejected or did not consider the possibility of surrounding Seoul, of cutting the roads to the northwest, north and northeast and forcing the capitulation of its garrison. This would have been a slower process, and would probably have reduced the psychological effect which bold and sudden victory, as MacArthur often said, could produce upon the Oriental mind. Whatever the reason, Almond’s decision to attack vigorously produced the holocaust through which the 1st Marine Division had to pass.”

Almond, in fact, ordered Smith to execute an attack into the center of Seoul on the night of September 25-26. Shortly after 8 pm on September 25, X Corps flashed a message to the 1st Marine Division ordering an immediate advance after aerial observers reported the “enemy fleeing city of Seoul on road north of Uijongbu.” Almond told Smith, “You will push attack now to the limit of your objectives in order to insure maximum destruction of enemy forces.”

A Flag Over the U.S. Embassy Once More

The NKPA was indeed pulling out of Seoul, but not all of it. Enemy counterattacks were launched that night against the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, in the hills just west of the city, and down Ma Po Boulevard against the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines. The 25th Brigade attacked fiercely down the boulevard in strength, with tanks and self-propelled guns, causing Smith to cancel his own night attack pursuant to Almond’s order. By daylight, the 1st Marine Regiment had killed 250 enemy and captured four tanks and two self-propelled guns in the Ma Po Boulevard fighting alone.

Before dawn on the 26th, the NKPA also counterattacked the 32nd Infantry’s positions on Nam-san, the 900-foot-high South Mountain on the edge of Seoul. One company of the 32nd was overrun on the mountain, but Colonel Beauchamp’s men stood their ground and drove the enemy off with heavy casualties. The 32nd Infantry, assisted by the 17th ROK Regiment, then pressed into Seoul proper in an effort to link up with Puller’s advancing Marines on the left flank.

Throughout the day, Puller’s Marines pushed farther up Ma Po Boulevard, but could gain only about a mile of ground in heavy fighting against the barricades. Meanwhile, Murray’s 5th Marines were struggling over a low hill mass before finally breaking into the city streets in the northwestern sector of Seoul on the morning of the 27th. By nightfall, X Corps troops controlled approximately half of the South Korean capital. Much fighting had ensued since Almond’s premature declaration of the city’s capture on September 25.

Seoul itself was a city in ruins. The American liberators were as shocked as the civilian survivors at the level of destruction. Pfc. Morgan Brainard of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines recalled seeing “great gaping skeletons of blackened buildings with their windows blown out, telephone wires hanging down loosely from their drunken, leaning poles; glass and bricks everywhere; literally a town shot to hell.” Private Win Scott of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, observed: “The city was dirty. There were animals running wild and junk everywhere. Some battles were fought around barricades formed by trolley cars. Pictures of Stalin hung on some of the buildings. Communist propaganda was all over.”

Despite the withdrawal from Seoul of the NKPA 18th Division along the Uijongbu road, the Allied drive into the heart of the city remained a difficult chore. But now key objectives were falling to the UN forces. The 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines recaptured the French embassy at 11 am on the 27th. That afternoon the Marines took back the U.S. embassy and elatedly if exhaustedly raised an American flag. The Seoul railroad station was also retaken in heavy fighting that the morning. The 5th Marines and the 7th Marines linked up, moving down toward the city from the north, and the 5th Marines took Government House in mid-afternoon.

President Syngman Rhee Returns to the Capital

In the meantime, another link-up had occurred. Just before midnight on September 26-27, tanks of the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry joined with the 7th Division’s 31st Infantry at Suwon, 27 miles south of Seoul, marking the junction of the X Corps with UN Eighth Army forces pushing north in the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter. The Communists elsewhere within South Korea were fleeing northward and disintegrating as an effective fighting force.

Within Seoul organized resistance continued into the evening of September 27 before slacking off into small-size firefights involving isolated groups of NKPA troops. By the morning of the 28th, relative quiet had descended on the city. The next day, MacArthur arrived in triumph in Seoul, accompanied by South Korean President Syngman Rhee. At noon in the National Assembly chamber, MacArthur made a formal pronouncement: “Mr. President, by the grace of a merciful Providence our forces fighting under the standard of that greatest hope and inspiration of mankind, the United Nations, have liberated this ancient capital city of Korea. I am happy to restore to you, Mr. President, the seat of your government that from it you may better fulfill your constitutional responsibilities.” President Rhee replied fulsomely to the general: “We love you as the savior of our race.”

Ironically, with the entry of the Chinese Communist forces into the war in full measure just two months later, Seoul would suffer another brief occupation. In pushing their way southward against the Eighth Army in early January 1951, the Chinese captured the capital, only to see the UN forces regain it for good in March, following a brilliant counteroffensive conducted by Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway. Seoul remained within reasonably close proximity to the fighting on the Korean Peninsula for the rest of the war, and its potential vulnerability to North Korean attack remains evident to this day.

A Brief but Bitter Battle

Casualties in the September 1950 retaking of the capital were relatively low by World War II standards, or even by the standards of the fighting along the Pusan Perimeter. Between September 20 and September 30, the 1st Marine Division suffered 1,716 casualties, of which 340 were killed in action or died of wounds. The heaviest losses occurred on September 24-25. The U.S. Army’s 7th Division suffered 106 killed, 409 wounded, and 57 missing in action after its arrival at Inchon on September 18. Total X Corps casualties for the entire Inchon-Seoul campaign beginning September 15 and extending into early October were about 3,500. The North Korean aggressors suffered an estimated 14,000 killed and another 7,000 taken prisoner.

In the final assessment, the battle for Seoul proved to be a relatively brief but exceedingly tough fight. The NKPA was willing to make a determined stand, although it had to know that ultimately it could not retain control of the South Korean capital. The North Koreans were outgunned and eventually defeated at Seoul, but thousands of civilians would not live to witness MacArthur’s ceremonial return of the city to the South Korean government. For them, no less than for the American Marines and soldiers and ROK forces who delivered them from Communist control, the price of liberty was high indeed.

Being an WW ll armchair history buff I have rarely read history of the Korean Conflict; this was a good article—— could we have more.

Thanks, David